WILL

At eleven o’clock the next morning, Lyn pokes her head around my bedroom door.

‘How are you feeling?’ she asks.

‘Pretty ordinary.’

‘Ken and I are going shopping. Can you look after Dave?’

‘Sure.’

I don’t know if it’s a hangover or the bump on my head or a combination, but my brain feels like an old computer that’s been taken to the tip – busted and rusted beyond repair. I gather up the energy to get myself out of bed. I have a shower, fix myself a flotilla of Weet-Bix, then sit back to watch the Sunday morning cartoons. When Duck Dodgers gets disintegrated, I know exactly how he feels.

I think about Mia inviting me to the concert and whether or not it’s a date. After all, we won’t be sitting together. We may not even get a chance to speak. But the fact is, Mia asked me to come, so headache or no headache, I’ll be there.

When the cartoons finish it’s midday and still there’s no sign of Dave.

I knock quietly on his bedroom door but there’s no answer.

‘Dave?’ When I turn the handle and try to open the door, it’s jammed.

‘Dave? Are you in there?’

‘Go away, Will!’

‘Are you still mad with me?’

‘I’m not talking to you, Will. You can’t make me.’

‘I’m supposed to be looking after you, Dave. I thought we could go and see Mia. We could take Harriet for a walk, if you want to.’

It’s an excellent offer – easily good enough, I would have thought, to lure Dave out of his room.

‘You can’t make me, Will.’

‘Okay, Dave,’ I say. ‘You wait here while I go and get Harriet.’

MIA

I slop on the wallpaper-remover and, like magic, the wallpaper peels away in long thin strips. The walls beneath are smooth and bare – as vulnerable as trees that have lost their bark. Should I paint them green, to go with the indoor ferns? Or should I paint bright butterflies, dancing in the sunlight?

The doorbell rings and Mum answers it. I hear footsteps coming down the hall and when I look up there he is, inside my house! Standing in my doorway, looking into my unfinished bedroom! Staring at my stripped walls before they’re even ready!

‘Will!’

He nods at the borrowed viola on my bed.

‘Shouldn’t you be practising for the concert tonight?’

‘Are you still coming?’

‘Of course I’m still coming.’

‘You don’t have to, if you don’t want to.’

‘I’ll be there, he grins. ’Even if I have to come on crutches.’

‘Even if I’m not the star of the show?’

‘Even if they don’t give out trophies.’

‘What are you doing here, anyway?’ I say. ‘Shouldn’t you be at home, resting?’

Will lowers his head to show me how the swelling has gone down. I am seriously tempted to run my fingers through his hair. I don’t, of course.

‘Actually . . . ’ he says. ‘Can I borrow Harriet?’

WILL

Dogs are smart. There’s no doubt about it. No animal has adapted better to a world dominated by humans. Instead of being put on the menu or hunted to extinction, dogs have worked out what people want. They know how to sit up and beg for food, how to bark at strangers or fetch a stick, and how to look knowing enough for people to think that their dog is their friend. But a dog is a dog. It’s an animal, trying to survive. It does what it can to get a bowl of meat and a safe place to sleep. I never wanted one as a pet, and I’m not about to be suddenly swept away by a cute little beagle.

After walking a couple of blocks together, Harriet and I have an understanding. We walk fast, with Harriet a step ahead and to the side. Yes, Harriet is excited to be out on the lead. No, we don’t stop to smell the lampposts or to annoy the barking dogs behind fences. Harriet walks with her head down and tail up, turning now and then to give me a reassuring glance: I’m Harriet, the sniffer dog, she says, off on another great adventure.

‘You don’t fool me, Harriet. But if you can get Dave out of his bedroom, I’ll buy you a nice big bone.’

Not a problem, says Harriet, with her doggy smile.

When we get home, I knock loudly on Dave’s door, but he doesn’t answer.

‘Dave! Come and see who’s here!’

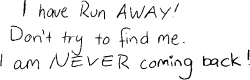

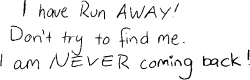

Harriet barks in excitement, but there is still no answer. This time, when I try the door, it opens. But the room is empty and on the bed there’s a note in Dave’s big, neat handwriting:

MIA

The wallpaper is gone. I have pulled down the curtains. The bedspread is packed away, ready for the op shop. Next on my list is the hideous chandelier.

I get a stepladder from the laundry and climb up it for a closer look. If it is possible to unscrew the crystal monstrosity, I will be happy enough with just a dim light bulb for now. I’m up on the stepladder, deciding how not to electrocute myself, when there’s another knock at the front door.

‘I’ll get it, Mum!’ I call out, assuming it must be Will, returning Harriet after her walk. I take off my glasses and neaten my hair, but when I open the door I get a shock.

‘Dad?’

Last night, as a doctor, my father was comfortable and relaxed. Now, as a father, he looks nervous and uncertain. When I go to kiss him, he doesn’t know whether to hug me or not. I don’t know if Mum wants me to invite him in or not. I don’t think I want him to see my room in such a mess, either.

‘It’s the big day!’ he says.

‘Yep.’ I nod. ‘The big day.’

‘I’m looking forward to it,’ he says.

‘Me, too.’

‘I got you something,’ he says.

‘You didn’t have to.’

My father goes to his car and comes back with my present. It’s in a long, rectangular box, wrapped up in plain brown paper. The card simply says: Sorry, love Dad.

I sit down on the doorstep and fumble with the wrapping paper, while my father watches nervously. Inside the box is a beautiful new viola.

WILL

‘You’re a bloodhound, Harriet! That’s what bloodhounds do – they pick up the scent and run with it. They hunt foxes and rabbits. They catch drug smugglers. They track down escaped prisoners. Now, help me find Dave!’

Harriet sniffs at Dave’s T-shirt then leaps into action. She tears down the hallway and disappears under the kitchen table, looking for food scraps.

I knew it was a dumb idea.

Dave has run away. He might be just around the corner, or he might be on the train to Alice Springs. Surely, because of his wheelchair, he can’t have gone too far. How can someone run away from home when they can’t even walk?

MIA

Mum invites Dad in and together they watch me tune my new viola and play a few arpeggios. My new viola is splendido e magnifico! The wood is darker than the old viola, with a finer, less distinctive grain. The bridge is cut differently and the f-holes are longer, but the feel of the neck and the tone of the two instruments are remarkably similar. My dad has gone to a lot of trouble in choosing it.

I close my eyes and pretend I am playing my old instrument. I pretend that nothing bad has happened – that my mum and dad still love each other and that the three of us are a normal, happy family. I play the arpeggios with more feeling and the tone of the instrument changes, becoming richer and more resonant. I realise, with tears streaming down my cheeks, that no two violas can ever be the same.

WILL

Harriet’s nose is a heavy-duty, industrial vacuum cleaner – a super-sniffer, sucking up smells, searching for clues. The first place we look is the tennis court. The Sunday lessons are on, and while I ask around, Harriet lets the kids play with her. By the time I am done, a tennis ball has been mauled, a toddler is crying and a four-year-old is throwing a tantrum: ‘I want a dog, Mummy! Tell Santa I WANT one!’ There has been no sign of Dave, though, so with no time to waste, we leave to continue our search. Harriet has no idea where we are going, but she’s dragging me there anyway.

At the shopping centre there is a sign on the automatic glass door. It shows an outline of a dog’s body inside a red circle with a red diagonal line crossing it out. It might mean NO DOGS, but it doesn’t actually say so. And the more I look at the dog in the picture, the less it looks like Harriet. Some breeds of dog are obviously banned from the shopping centre, but surely not tracker dogs here on urgent business.

Harriet and I sneak into SportsWorld and begin sniffing around for traces of Dave. We snoop around Swimwear and creep through Cricket. We slink past Skiing and tiptoe through Tennis. There are racquets on special so surely Dave must be here, hiding in a change room or eyeing off a new pair of trainers. SportsWorld is a big, busy store, but when Harriet starts making new friends, it’s not long before we’re noticed by the staff.

‘Excuse me,’ says the girl. ‘Your dog is not allowed in here.’

‘She’s not my dog,’ I say, hoping to buy some time.

The girl gets the section manager, the section manager gets the store manager, then the store manager gets the security guard. By the time the guard arrives, I have staked out the entire store and Harriet is tearing around the astroturf with a gang of squealing children.

‘Let’s go, Harriet. We’re done here.’

Outside the sports store, the food court is thundering with noise as people clatter their cutlery and slurp their cappuccinos. Out of desperation, I buy a two-dollar pair of sunglasses, hoping that people will think Harriet is my seeing eye dog. The trouble is, seeing eye dogs are known to stay cool in a tense situation, whereas Harriet is a dead giveaway – jumping up on tables, trying to lick kids’ ice-creams. There are too many different smells here for an innocent young bloodhound. Harriet’s nose is in danger of being overloaded. She could rupture her sinuses or blow a nose-gasket.

Instead, I tie her up outside the door and wander among the tables, searching without much hope for a sign of my runaway brother. How ridiculous am I, to be taking Dave’s note so seriously? But time is slipping away and I am starting to panic now. What if Dave really means it? What if he really has run away? Dave might have even made plans – a refuge for the disabled, a motorised wheelchair, a getaway van with a ramp up the back. Or worse, Dave might be in trouble. He might have done something stupid.

When I return, Harriet has wound her leash round the pole, until she can’t move her head. As a prisoner of her own stupidity, she is paying the price – a boy and his sister are mercilessly tickling her tummy and Harriet’s hind leg is scratching the air in ecstasy.

I unwind her leash and we’re away again, with Harriet relentlessly dragging me on.

At the swimming pool she makes her grand entrance, barking madly at the startled swimmers and wanting to leap into the water to join them. Surely Dave will be here, arguing with the lifeguards or wrestling with the vending machine? As I survey the lap-swimmers, the rowdy kids doing bombs or the soakers in the spa, I can hardly bear to look. At any moment I expect to see Dave, floating lifelessly in the water.

But no, he’s not here, which means he’s somewhere else. But where?

I am running out of possibilities.

The park, of course! Of course, Dave is in the park – doing his chin-ups, proving to himself, yet again, that he’s stronger than his big brother. The park is the place I should have looked first. Dave isn’t running away. He’s in the park, waiting patiently to take Harriet for a walk.

The park seems like a long, long way from the pool. It’s a sunny afternoon and by the time Harriet and I get there we are both panting loudly and soaked in sweat. The park is deserted. There is nothing but trees and grass in every direction. Out of desperation, I let Harriet off the leash and she runs away, spurred on by some unknown excitement. I follow her at a distance, doing my best to keep up as she speeds towards the chin-up bars, barking with excitement.

There, on the ground, I see something that lifts my hopes like a wave, then smashes them against the rocks.

It is Dave’s empty wheelchair, collapsed and lying on its side.

MIA

‘Should we call the police?’ Mum asks, on the way to rehearsal.

‘Definitely not!’

‘What about Harriet? What if something has gone wrong?’

‘Will is probably . . . caught up in something,’ I say, trying to sound convinced.

‘Is he coming to the concert? Does he know when it starts?’

‘He knows . . . He’s coming.’

‘Well, I hope he’s not late. Remember, he’s already let you down once.’

‘He won’t be late, Mum . . . He’d better not be.’

WILL

Dave has disappeared into thin air. Dave has evaporated. He has been abducted, assassinated, sold into slavery, murdered. Harriet is barking up a tree, but it’s the wrong tree. There is no sign of Dave in any direction.

‘Dave!’ I shout. ‘Where are you?’

No answer. Not even an echo.

Harriet suctions the folded wheelchair for clues, then suddenly takes off across the grass in the direction of the lake. There’s a big clump of reeds growing by the water’s edge. Maybe Dave has crawled in there or been dragged in there by some mutant urban THING! Harriet is almost to the reeds when she hears another dog barking. From across the park, a mongrel comes running – a big ugly bruiser of a dog without a collar. Harriet stops. With her tail in the air she turns to face the new dog, which wastes no time in sniffing her out. But before Harriet has time to return the compliment, the brute is snarling. Harriet’s tail drops. She yelps and tries to run, but the heavyweight mongrel grabs her by the throat and starts to shake her violently, trying to break her neck.

‘GET AWAY!’

I pick up a stick and run towards them. When the mongrel sees me coming it releases Harriet and bares its teeth. Instead of turning to run it snaps its jaws again and – like Iron Mike Tyson – bites off a piece of Harriet’s ear. Only after I hit it hard across its back and kick it does it finally run away.

Harriet is instantly on her feet, barking excitedly with blood streaming from her mauled ear. From a tree beside the lake, I hear a wild thrashing of leaves. I look up and see Dave, half-falling, half-climbing down from way up high. A twig snaps and I watch in horror as he topples head over heels, clears the lowest branch and lands, somehow, on his feet! For what seems like forever, he stands in that miraculous position, screaming at the fleeing mongrel, before finally sinking to his knees.

‘Dave!’

‘Call an ambulance, Will! We’ve got to get Harriet to hospital!’

MIA

I show Ms Stanway my new viola while the orchestra is setting up on the stage. Ms S inspects it briefly, plays a few bars and tells me I am a lucky girl. The musicians are tuning their instruments, playing their scales and running through their different parts. There is no sound on earth so chaotic yet so full of expectation as an orchestra tuning. Ms S runs through her reminder notes, then she has a pink fit about how we will take our bows and in what order, who will carry their instruments and who will leave them behind. In the time remaining, we play the Vivaldi – all twelve movements – stopping only once, when the woodwinds launch in two bars early. I play my parts without a mistake, but even on my new viola it is hard to play with passion. My eyes follow the notes without reading them and my fingers go through the motions. Whenever anyone arrives or leaves the hall, I look up hoping to see Will.

WILL

Dave and I sit in the waiting room while behind the white door, the vet stitches Harriet’s ear. I have never seen Dave so worried. He wriggles and fidgets and keeps asking questions.

‘Will Harriet have a general anaesthetic, Will, or just a local?’

‘I don’t know, Dave.’

‘Will it hurt, Will? Will she be scared?’

‘She’s a brave little dog, Dave.’

‘Will she be okay, Will? Will she still be able to hear?’

‘I’m sure she’ll be fine.’

‘Will you miss the concert? Will Mia be mad at you?’

‘I hope not, Dave.’

‘It wasn’t our fault, Will. It was that other dog. Why was it so angry?’

‘Some dogs are bred to fight, Dave.’

‘Why do people have dogs like that, Will?’

‘Some people are like their dogs, Dave. They’re bred to fight.’

‘But we weren’t scared of it, were we?’

‘I was a bit scared, Dave.’

‘Me too, Will.’

‘You didn’t look scared, Dave. You looked angry.’

‘Dogs know it when you’re scared, don’t they, Will? They can smell fear.’

‘Everyone can smell it, Dave.’

‘Is that why you lost the tennis match, Will?’

‘I guess it is.’

‘But you’re not a choker, Will. You weren’t scared of those boys at the party.’

‘I was a bit scared, Dave.’

‘Did you ever feel like running away, Will?’

‘I think everyone feels like running away sometimes, Dave.’

‘It would be pretty stupid if everyone ran away, Will. Where would they all go?’

‘How did you get up that tree, Dave?’

‘I climbed, of course.’

‘But how did you get there without your wheelchair?’

Dave grins. ‘What? Do you think I’m disabled?’

MIA

Boys are unreliable. They are fundamentally, genetically and primordially unreliable. They will do anything to try to meet you, but then they can’t talk. They will invite you to the tennis, even though they can’t actually be there. They will trample your flowers. They will treat you like cattle. They will sleaze around with your ex-best friend. They will promise to come to the most important event in your life, but instead they will steal your dog and never come back. Will Holland is unreliable – he cannot be relied on. If this were a tennis match; if I was an athlete, instead of a musician; if there were any gold medals to be won or toe-sucking to be had, I’m sure things would be different.

Slowly but steadily, the clock ticks down to starting time. The doors open and people begin to stream in. They take up their seats and start reading their programs – all the mums and dads and brothers and sisters and grannies and grandpas and aunties and uncles, come to see the concert, come to be reliable. Mum and Dad arrive together, but not together, if you know what I mean. I give Mum a hopeful look and she shakes her head grimly. No Harriet. No Will. Nothing to rely on.

The lights of the house go down and Ms Stanway walks onto the stage. She welcomes the audience and tells them about the composer.

‘Antonio Vivaldi was born in Venice in the seventeenth century. A prolific composer and a virtuoso violinist, he was rich at the height of his fame but died in poverty. Of the 500 concertos he wrote, the most popular were four known as Le Quattro Stagioni – The Four Seasons.’

The audience applauds as Ms S takes up her baton and turns to face the orchestra. We raise our instruments and with a nod from Ms S we’re away! Allegro – the first movement of ‘Spring’. It’s the catchy, melodic, swingy, springy movement that everyone instantly recognises and the orchestra knows off by heart. There are a few tricky bits where the violins spin and weave like butterflies, then a fast bit for the strings, which we play almost perfectly. Ms S is smiling. All her hard work is paying off.

When the first movement ends, there’s a brief pause before the second – largo e pianissimo sempre. As the players turn the pages of their sheet music, preparing to start, there’s a sound as explosive as gunshots, coming from the back of the hall.

Someone is clapping!

WILL

Dave and I sneak in the door as the orchestra is starting. There are no empty seats. If Dave hadn’t been in a wheelchair, we might not have been let in. We move to the back corner without being noticed, but when Dave starts clapping at the end of the first movement, people turn around in disgust. When they see who he is, their angry stares change to amusement, which in my book is even worse. Instead of telling Dave to stop clapping, I join in.

The second movement of ‘Spring’ is a quiet, gentle number. It’s impossible to say for sure what the music is all about, but because it’s called ‘Spring’, I imagine a garden. The sun is shining and bees are buzzing all around between the brightly coloured flowers. One bee is going about its business when it notices a particular flower. The more the bee looks at this flower, the more and more beautiful it seems. In the third movement, the tempo picks up and the bee starts to go a bit crazy. It buzzes around and around the flower, but doesn’t have the nerve to land. In the end the bee returns to the hive, sad and honey-less.

When ‘Summer’ comes, everything slows right down. The orchestra has a siesta while the first violinist kills a few blow-flies, turns on the fan and grabs a cool drink from the fridge. In the second movement, he puts his feet up and watches the cricket, then in the third everyone piles into the car and heads off to the beach. The sky is blue and off in the distance two white yachts are racing across the sparkling water. When they get to the floating buoy, one turns around while the other keeps on going. It’s all very deep and meaningful.

‘Autumn’ starts with a bang. It’s as if there’s a big game of football between two old rivals. After getting off to a good start, the game begins to get messy. Someone kicks the ball out of the stadium, then the players start fighting and the umpire accidentally gets flattened. The second movement is slow, like falling leaves. The footy game has been abandoned and now everyone is out in the park, helping to rake up the leaves. They make a pile as big as a bonfire, then in the third movement, someone lights a match and the whole thing goes up in smoke. It makes a beautiful blaze, though.

When ‘Winter’ comes, the scene shifts to Antarctica. There are mountains of ice and glaciers breaking up into icebergs. In the howling wind, weary explorers are trudging knee-deep through the endless snow. In the second movement, one of the explorers falls down a crack and has to be thrown a rope. It’s a tense situation, but they finally get him out, unharmed. By the third and final movement they’re all back at base camp, enjoying a cup of hot chocolate. It’s a bit of an anticlimax, really.

Suddenly everyone in the audience is on their feet, applauding loudly. For the entire concert the only noise between movements has been old people coughing, babies crying or Dave asking me if he can clap yet.

‘Go for it, Dave!’ I say.

The two of us let rip, stomping and whistling until Ms Stanway walks back on stage. The audience sits down as the orchestra prepares to play an encore.

The encore they choose is ‘Spring’, so that the concert ends as it started and the seasons continue in an unbroken cycle. Just when you think things are all over, they’re starting up again.

I look up at Mia and she sees me. I give her a big thumbs up, to say that Harriet is fine, and she smiles and mouths the words ‘Thank you’, as if she can guess what we have been through.

It’s spring, all over again.

MIA

After the show there are coffee and biscuits out in the foyer. I talk to Mum and Dad, then I talk to someone else’s mum and dad, then someone else’s grandma and grandpa. Everyone says what a wonderful concert it was and how beautifully we played. It doesn’t matter that I’ve never seen these people before and will probably never see them again. It feels like one big happy family.

Will and his brother are there in the corner, and finally I get a chance to speak to them. But before Will can say anything, Dave is pumping my arm and raving loudly.

‘It was fantastic, but we almost didn’t make it! Poor Harriet! But she’s okay, don’t worry. I loved The Four Seasons, especially the bits when everyone played at the same time. It was so loud! Are you doing another concert, because if you are I want to come. Do you have a CD? Where can I buy it? Tell her that joke, Will – the one about the viola and the trampoline!’

I turn to Will. ‘What happened to Harriet?’

‘She’s back at our place,’ he says. ‘She was helping me find Dave.’

WILL

Mia wants to see Harriet. Her Mum says it’s okay, so she and Dave and I walk home together. Dave is lapping up Mia’s attention. He tells her in gory detail all about Harriet’s fight, and how he jumped out of a tree to save her.

‘I’ve decided I don’t want to run away from home,’ he says. ‘I want to play in an orchestra. I want to learn an instrument like that black one with all the knobs and the silver blower on the end. Will says it’s called a baboon!’

Harriet is in our laundry, curled up on an old blanket. She’s sedated and bandaged but happy to see us. Mia has tears in her eyes as she kneels down beside the little beagle to give her a loving hug.

‘You were so brave, girl. There are some nasty dogs out there.’

Harriet is not to be moved, so Mia promises to come back in the morning. When I offer to walk her home, Dave is already halfway out the door.

‘What about me, Will? Can I come, too? What do you think, Mia? Would that be okay?’

Mia takes Dave’s hand, which shuts him up better than a roll of masking tape.

‘Another time, Dave,’ she says. ‘Will and I need to talk.’

MIA

It’s a warm, misty night. Will and I walk slowly along the main road, looking in the shop windows, reading the price tags, feeling the tiny droplets on our skin and hearing the occasional swish of a passing car. We don’t really need to talk. We don’t need to talk about the concert. We don’t need to talk about music or sport. We don’t need to talk about Harriet or Dave. We don’t need to talk about our parents or our friends, about the past or the future. We don’t need to talk about feelings or facts, about being reliable or redecorating our bedrooms. It’s warm and misty with the feeling of invisible raindrops in the soft night air. Will and I are happy just walking. We don’t need to talk . . .

WILL

Talk? What is there to talk about? Don’t forget V! Is Mia still upset about Vanessa? Or has she fallen in love with the first violinist? (V for Virtuoso?) If Mia wants to talk, then why isn’t she talking? Does she expect me to launch into an apology when I didn’t even kiss Vanessa? Or is she waiting to break the news gently about her and the talented Mr V? Should I say something? Should I break the ice? Should I apologise one more time about Harriet? Should I tell her how beautiful she looked up on the stage?

Mia and I walk on in silence up the main road. Ahead of us, the hands on the clock tower are covering the twelve. Either it’s midnight or the clock is broken. Mia stops walking and turns to face me. This is it – the big V – the thing she wants to talk about.

‘Look up in the sky,’ she says.

Mia looks like Cinderella, but I think I’m about to get hit by a falling pumpkin.

MIA

I ask Will, ‘What do you see up there?’

He looks uncertain. ‘Clouds?’

‘Do you ever think about raindrops?’

‘Raindrops?’

‘Did you ever think about what happens when two raindrops fall on the top of a mountain? One raindrop rolls down one side of the mountain, then into a stream, then a river, before it gets swept away into the sea. But the other raindrop runs off in a different direction, down into a different river, then off into a different ocean, maybe. The two raindrops started off so close but then ended up so far away.’

‘Maybe one day,’ says Will, obviously choosing his words carefully, ‘they might meet again, in the clouds.’

‘Is that possible, do you think?’

‘I’m sure it is.’

WILL

There is no pumpkin! There is no V! Mia is a modern-day Cinderella who doesn’t care what time it is, a.m. or p.m. She doesn’t want to fight with me. She just wants to talk about the weather! We leave the main road and walk through empty suburban streets with their parked cars and leafy trees, their picket fences and immaculate gardens. It feels like just the two of us now, while the rest of the world is asleep.

‘What do you throw away when you need it,’ she says, ‘and pick up when you don’t need it?’

‘I give up. What?’

‘It’s a riddle,’ she says. ‘I’m not telling you. You have to work it out.’

‘What do you throw away when you need it . . . ’ ‘ . . . and pick up when you don’t need it?’

‘A light switch?’

‘Wrong!’

‘Chewing gum?’

‘No.’

‘You’re not going to tell me, are you?’

‘Sorry.’

‘But I might never guess. I might go to my grave without knowing the answer.’

‘That would be sad.’

‘Secrets?’

‘Incorrect.’

‘Time?’

‘Hmm . . . no.’

‘A friend?’

‘I hope not.’

‘A boomerang? A yoyo?’

‘No . . . and no.’

‘Underpants, astronauts, Eskimos?’

‘You’re not really trying anymore, are you?’

MIA

Will and I have come to a crossroads. All the streets look the same – north, south, east and west. There is a roundabout like a grassy green island with a big leafy tree in the centre. We sit down like castaways, feeling stranded and invisible behind a curtain of mist. It is after midnight but instead of feeling tired, I am almost dizzy with excitement. It doesn’t feel late anymore, it feels early.

‘Can you give me a clue?’ he says.

‘I feel as if we’re floating,’ I say.

‘Floating?’ Will thinks for a while. ‘A lifebuoy?’

‘A lifebuoy gets thrown at you, doesn’t it?’

‘I’ve got it!’ he says suddenly.

‘What is it?’ I say. ‘What do you throw away when you need it and pick up when you don’t need it?’

‘An anchor!’

‘Yes!’ I say, holding out my hand.

Will takes it and squeezes gently.

‘You’re my anchor,’ he says, softly.

WILL

Love is an anchor – it stops you from drifting away. Love is sticking up for your friends and family, or even your pets. Love is being brave and saying what you feel. Love is making music or playing tennis, it’s doing what you want to do. Love is holding on and not letting go.

MIA

Will’s hand feels soft and warm in mine, but also strong and determined. I feel his grip tighten as I gently pull towards him . . .

WILL

. . . and we . . .

MIA

. . . kiss!