8

To Grasp the Thorns of Victory:

Afternoon – Evening, 12 July 1691

Their step cadenced by a monotonous drumbeat, the Danish line began its steady, almost inexorable progress towards the Jacobite positions around the Attibrassil Bridge. On the extreme right of the line came the two squadrons of Maj-Gen La Forest-Suzannet’s regiment of horse and to their left marched the single white-coated battalion of the sixteen-year-old Prince Christian, in his absence commanded by the fifty-four-year-old Hessian, Johann Elnberger, who would survive the war only to be beheaded for cowardice in 1695 following the surrender of Dixmuide to the French. Next in line came the two squadrons of von Donop’s horse, one of which had been bloodied in the initial scramble for the approaches to the bridge, and next to them the line was continued by Crown Prince Frederik’s Regiment of Foot, distinguished by its dark blue coats with red facings, and led by another German soldier of fortune, Wolf Heinrich von Kalneyn, a Prussian who had entered Danish service as a captain, in 1677. The battle line was extended by the third of the Danish cavalry regiments, that of the forty-two-year-old Colonel Jens Maltesen Sehested and by the white-coated infantry of Prince George of Denmark, younger brother to King Christian V and husband of Princess Anne of England, the future Queen Anne.

Advancing parallel to the Danes, and covering their left flank, came a Dutch regiment of horse commanded by a Huguenot exile, Paul Didier de Boncour, and the Gardes te Paard, whose command had presumably devolved upon Ritmeester Johan Pauw, Count van Rijnenberg, and completing the line came the by now-reformed squadrons of van Eppinger’s Gardes Dragonders.

In total, the attack force under von Tettau’s direct command came to some 2,000 foot, 1,000 horse and 500 dragoons, giving them numerical parity with the Jacobite troops waiting on the far side of the Tristaun Stream, while Maj-Gen Hendrik van Nassau-Ouwerkerk waited 100 paces to the rear, at the head of a second column whose task was to move through von Tettau’s bridgehead and roll up the Jacobite line by falling onto the now-exposed enemy rear. The mainstay of van Nassau’s command were two remaining Danish foot battalions – the green-and-white clad Fynske, commanded by Hans Hartmann von Erffa, and the red-and-yellow clad Zealand, whose colonel was von Tettau himself.

To the right of the Danes stood van Nassau’s own command, the Dutch Garde du Corps (Gardes te Paard van Zijne Hoogheid), and the horse regiment of Bogislaf Sigismund Schack, whilst to their left had formed the horse regiments of Robert, Baron Ittersum tot Nyenhuis, Godard van Reede (the commanding general, but led in the field by his son Frederik Christiaan), Erik Gustaf van Steenbeck, and Armand Caumont de la Force, Marquis de Montpouillon, with the line being closed by the remaining troops of Sir Arthur Conyngham’s Enniskillen dragoons.

Although his unit was unengaged at his point in the battle, one Anglo-Irish officer, the twenty-nine-year-old Richard Kane, serving as a major in the Earl of Meath’s Regiment of Foot, gives in his memoirs a clear and effective summary of the plan and its eventual development:

‘Our general began the battle at about four in the afternoon by attacking them on their Right, and so gradually on until our Right (where was our regiment) engaged those on their left that lined the garden-ditches. Our troops, that engaged their Right and Centre, were hard put to it for a considerable time, and were several times repulsed, the Enemy having maintained their ground in those parts with great resolution.’

Born Richard O’Cahan in Duneane, Co.Antrim in 1662, Kane had had his name anglicised in 1688 following the accession of William and Mary, a tangible demonstration of his political loyalties. In 1689 following the outbreak of hostilities in Ireland he enlisted in Viscount Massereene’s Regiment of Foot – a regiment of Ulster Protestant volunteers – eventually being commissioned as a lieutenant in the regiment’s 4th Company, commanded by his cousin, Captain John Dobbin.

Following the disaster at Dromore on 14 March 1689, where the regiment had been commanded by Massereene’s son and heir, the Honourable Clotworthy Skeffington, the regiment withdrew to Derry where it was subsumed into one of the newly-formed garrison regiments and came under the command of Colonel John Mitchelbourne, previously the regimental Major. Following the siege, Kane transferred to the Earl of Meath’s Foot (formerly Arthur Forbes’) which had landed near Belfast in August 1689 as part of the Duke of Schomberg’s army, seeing service at the Battle of the Boyne and the first siege of Limerick before Ginkel assumed command of the army, by which time he had risen to the rank of Major. Following the end of the war in Ireland, he would transfer to Flanders, eventually fighting under Marlborough’s command at the battles of Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenaarde and Malplaquet and subsequently the ill-fated Canadian expedition of 1711. In 1712 he was appointed Lt-Governor of Menorca, an island that he governed for over a quarter of a century until his death in 1736.

From their command position on the southern slopes of Kilcommodan Hill, Sarsfield and de Tessé could see the enemy attack slowly developing. Several thousand enemy troops were relentlessly moving on a position held by a little over half that number – a position which would become harder to defend the closer the enemy were able to come. With the defence resting on the premise that the Williamites would not be able to force their way across the adverse terrain, its key lay in the versatility of the five dragoon regiments under their command and the ability of these men to harass and delay the enemy’s advance, sniping from behind cover. Conversely the Life Guards and the horse regiments, the élite of the command, had now been relegated to an almost secondary role – that of launching limited local counter-attacks should the opposing troops force their way across the Tristaun Stream. But what was truly needed was infantry support, and although word had by now reached them from St Ruth confirming the imminent transfer of troops from the centre, this was of little immediate comfort to both commanders as it would take some time before the infantry could filter into their new positions; von Tettau’s steady advance would shortly render their forward positions on the far side of the Tristaun Stream untenable.

Until now, the dragoons deployed in the morass had successfully achieved their objectives, by harassing the enemy’s forward units, but the whole premise of their advanced position was based on the fact that in occupying the marshy ground they would be inviolate against the spearhead of an enemy attack. If the opposing forces were mounted, they would be unable to enter the bog on horseback and could be engaged at range, whilst if they were dismounted, then the dragoons should theoretically be able to manoeuvre so as to remain out of close combat whilst still continuing to fire upon the advancing troops.

In theory it was a perfect strategy, but it had two inherent flaws. The first was quite simply that, in order to occupy the morass, the Jacobite dragoons would have had to have left their own mounts on the far side of the Tristaun Stream and were thus handicapped when it came to the superior mobility that normally separated them from both foot and horse. The second, and potentially more dangerous flaw was that their position was in danger of being imminently engaged by a mixed force of enemy troops: if they stayed in position so as to avoid the cavalry, they would be pinned and caught by the advancing infantry, while if they continued to skirmish and withdraw in the face of the infantry they would soon run out of room to manoeuvre and be forced into the open, where they would be at the mercy of the cavalry. Seeing this, Sarsfield and de Tessé had no realistic option other than to withdraw the dragoons and use them to thicken the defensive lines at the bottom of Kilcommodan Hill where possible.

Continuing their almost relentless advance, von Tettau’s troops ran into difficulties when they entered the morass, being forced to break formation, with the three Danish infantry battalions temporarily halting to realign themselves and with the Dutch and Danish horse redeploying onto the firmer ground to the south. It is unclear how the Williamite dragoons were deployed at this point, although given Ginkel’s intention of persuading the enemy that this was the beginning of a major attack around the southern slopes of Kilcommodan Hill to cut the Limerick Road and roll up the Jacobite right flank, it is most likely that they dismounted and extended the Danish line in order to pin as many of the defending forces in position as was possible.

With von Tettau’s and Le Forest-Suzannet’s troops coming close to their objective, Ginkel now gave the signal for the next two brigades in sequence to advance and develop the planned attack in echelon which would fix the Jacobite right flank infantry in position, preventing them from aiding the threatened sector and, by definition, both magnifying and maintaining the credibility of this advance as the main attack, thereby forcing St Ruth to draw troops from unengaged sectors. The front line was commanded by Colonel Isaac de Monceau de la Mélonière, leading a brigade of four battalions, the first three of which were formed from white-clad French Huguenot exiles – his own regiment, and those of colonels Francois du Puy du Cambon, and Pierre de Belcastel de Montvoillant, Marquis d’Avéze, with the brigade being rounded off by the Dutch regiment of Lodewijk Fredrik van Auer.

Recruited almost exclusively from Protestant Frenchmen who had chosen to go into exile after Louis XIV’s revocation – in October 1685 – of the Edict of Nantes and its subsequent replacement by the Edict of Fontainebleau, William soon had a cadre of former French soldiers at his disposal. On 1 April 1689, he raised three regiments of foot and one of horse (initially commanded by the Duke of Schomberg, but following his death at the Boyne, the regiment passed to the Marquis de Ruvigny). Although the unit had experienced little of combat, the combined experiences of its men in the service of France set it amongst the best-trained and motivated units in Ginkel’s army, their service in the Williamite ranks providing a method by which they could strike out at Louis for his persecution of their co-religionists. In support of the Huguenots came a second brigade of three battalions, this being commanded by the twenty-one-year-old Prince Georg, third son of the Landgraf Ludwig VI von Hesse-Darmstadt.

As a younger son, and unlikely to inherit to the family titles the Prince, in 1686 – like many of his class – had embarked on the ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe, but upon his arrival in Vienna, he brought his sightseeing to an abrupt halt, deciding instead to enlist in the Imperial army to serve against the Turks. A contemporary, therefore, of both the Duke of Berwick and the Duke of Württemburg-Neustadt, he saw combat under Charles V of Lorraine and Maximilan II Emmanuel of Bavaria at the Battle of Mohács in 1687. Following the conclusion of his Imperial service, he travelled northwards to the United Dutch Provinces and offered his sword to William III for his Irish campaign, being rewarded with a commission as major-general of foot.

As with de la Mélonière’s Brigade, Hesse-Darmstadt’s troops were also numbered amongst the better of the Williamite units: the first two battalions being commanded by Prince Georg himself, (previously Colonel Philip Babington’s) and by Colonel Lord John Cutts. Both regiments having been raised in 1674 for service with the Anglo-Dutch Brigade, one of two ‘Treaty’ formations formed for Dutch service. The third regiment in the brigade was an English battalion under the command of Colonel Thomas Lloyd, and the fourth a Dutch regiment led by Ferdinand van der Gracht, Heer de l’Écluse who had recently taken over command from Frederik-Lodewijk, Graaf van Nassau-Ottweiler.

Having given von Tettau’s flanking manoeuvre sufficient time to develop and, more importantly having given St Ruth sufficient time to react, de la Mélonière and Hesse-Darmstadt began their own advance upon the Jacobite front line, arguably the most important movement by the Williamite forces during the course of the entire battle. Mackay’s assumption was that upon perceiving a threat to his right flank, and therefore to his lines of communication with Limerick, St Ruth would only be able to counter the threat by transferring troops from an unengaged formation, in this case Hamilton’s division, but if Hamilton’s forces were themselves committed, it would mean that any reinforcement for the threatened sector would have to be provided by Dorrington, furthest from the scene of the action, and thereby weakening that part of the Jacobite line against which Mackay had suggested that Ginkel launch his main attack.

On the extreme left of the Williamite line, the terrain had yet again dictated an amendment to the original plan of attack, with the mounted troops being relegated to the role of the observers awaiting the creation of a breach in the enemy defences which they could exploit – conversely, the Jacobite horse, deployed on the southern slopes of Kilcommodan hill faced a similar situation as they could really only be deployed to counter any Williamite breakthrough. As the Danish foot cleared the morass, they came under fire from the dismounted Jacobite dragoons concealed in the hedgerows lining the Tristaun Stream who maintained a steady fire in the face of the oncoming troops.

In his A Continuation of the Impartial History of the Wars of Ireland, the Rev. George Story, then serving as a chaplain in the Williamite army, wrote of the Danish advance:

‘A Party of our Foot marched up to their Ditches, all strongly guarded with Musketeers, and their Horse posted advantageously to sustain them; here we fired one upon another for a considerable Time, and the Irish behaved themselves like Men of another Nation, defending their Ditches stoutly; for they would maintain one Side, till our Men put their Pieces over at the other, and then having Lines of Communication, from one Ditch to another, they would presently post themselves again and flank us’.

Discommoded by the sun shining directly in their faces, the Danes inched their way forward answering the enemy musketry, but unable to clearly distinguish their targets, until they came up to the stream itself. Bracing themselves after a close range volley, the battalions launched an attack upon the hedgerows, only to find that after the last exchange of fire the Jacobite dragoons had evacuated their positions and, as the leading elements attempted to cut a way through the undergrowth, a second line of enemy troops began to pour fire into the newly occupied positions. Unable to fully utilise his numerical superiority, von Tettau’s attack had, temporarily at least, ground to a halt and with thickening lines of Jacobite troops visible on the southern slopes of Kilcommadan Hill, he was obliged to go over to the defensive.

That von Tettau’s command was forced onto the tactical defensive is confirmed by the Duke of Württemburg-Neustadt in his official correspondence to the Danish Government. In translation, he recorded that the Danish Foot fought from behind their chevaux-de-frise, this is however a possible misinterpretation as it would have meant that the Danes would have to have carried the logs and sharpened stakes which are used to construct these devices the length of the battlefield, to the point from which they launched their attack, across the morass and up to the Tristaun Stream itself. A more likely version is that they utilised the defences constructed by the Jacobites as protection against local counterattacks made by the Irish Horse.

Led by de la Mélonière, the Huguenots had slowly but manfully forced their way through the clinging mud which, in places had reached to their waists and – in some disorder – had begun to form up on the far side of the bog. To their front lay a shallow defile, and believing that it would offer them egress onto the lower slopes of Kilcommodan Hill from where they could continue their supporting role for von Tettau’s attack, the brigade moved forward, with Belcastel’s Regiment in the lead, closely followed by the remaining two battalions, following the passageway into a bowl-shaped declivity. Compressed by the terrain, and closely pushed from behind by their comrades, the Frenchmen were unable to deploy properly and, hemmed in by the steep slopes, unable to advance, instead becoming a sitting target for the Jacobite troops above them – ironically enough, as the firefight continued, the enclosed nature of the terrain meant that the smoke engendered by the black-powder muskets failed to completely disperse, thereby giving the Huguenot infantry some much-needed concealment from the enemy fire.

While Belcastel’s men tried to find what cover they could and began to return the enemy fire, de la Mélonière led his remaining battalions northwards, along the base of the hill, in an effort to find an access point which they could use to relieve the pressure on their compatriots. To the rear of the Huguenot brigade, Hesse-Darmstadt had seen the advance grind to a halt and the troops beginning to fan out northwards. Correctly deducing that forward progress was no longer possible he realigned his troops, changing their line of advance so as to come in on the flank of the northernmost of the Huguenot battalions.

At their command post near Kilcommodan Church, both Sarsfield and de Tessé had reason to be satisfied with their performance so far: since the early afternoon, two enemy attempts to seize the Attibrassil Bridge had been beaten back with heavy losses, and although the outlying positions had by now been abandoned in the face of von Tettau’s determined advance, everything had proceeded as outlined in St Ruth’s original plan of defence. The Danes were being comfortably held along the first line of entrenchments and their request for reinforcements had by now been met by the arrival of two battalions of foot from Hamilton’s division – as long as the enemy could be contained and thereby prevented from breaking out, the army’s right flank remained safe.

Unaware that he was living his final few hours, and from his own command position further north and further upslope on Kilcommodan Hill, St Ruth must have felt content with how the battle was now developing. Like Sarsfield and de Tessé he had already seen the Williamite attempt to turn his right flank become bogged down, unable to make much progress over the prepared defences while below him, and with undoubtedly a decent measure of schadenfreude he could make out the indecision amongst the Huguenot ranks as they strove to find a route by which they could ascend the hill and come to grips with the waiting Jacobites. Across the valley, he would also have been able to make out Ginkel’s headquarters and, placing himself in his adversary’s position would no doubt have felt the first stirrings of victory: It was by now late afternoon, around 1720, with only a few hours of daylight remaining, and it was plain to see that the enemy’s main thrust was going nowhere. Given the adverse terrain over which it would have to cross, it was too late in the day to launch another attack and indeed, common sense dictated that rather than incur unnecessary losses, a commander as cautious as Ginkel was known to be should call off the assault and regroup his forces for another attempt on the following day.

For the Frenchman, this would have been the perfect end to the day’s fighting: his position would be no less strong on the following day, and the repulse of the enemy’s left wing could not only have an incalculable effect on morale but would also serve to silence those critics who had found fault with his decision to engage the enemy in open battle. It was true that von Tettau’s attack had shown an apparent weakness in his deployment and had caused him to redeploy a number of battalions from their assigned positions, but this was only to be expected in a battle where his plan was to follow a reactive strategy.

The northernmost sector of the battlefield, and effectively the army’s left flank, had by now lost the two regiments of foot that had been deployed to the rear of Aughrim village and had now been transferred to Dorrington’s command to compensate for the earlier loss of two battalions (as part of the sideways movement to reinforce Sarsfield and de Tessé), but the narrow causeway over which the Athlone–Galway Road passed was still covered by an emplaced artillery battery and a detachment of 200 musketeers from Colonel Walter Bourke’s Regiment of Foot manning a series of entrenchments dug in and around the ruins of Aughrim Castle. As an added security Dominic Sheldon’s mixed brigade of horse and dragoons was still placed to their rear, well situated to engage any enemy troops which forced their way across the causeway while elements of William Dorrington’s command, on the northernmost slopes of Kilcommodan Hill, were also in a position to engage any Williamite movement to force a crossing. The loss of a thousand infantry was a light enough price to pay to ensure the security of the whole battle line.

Indirectly, this Jacobite redeployment would highlight hitherto unanticipated tensions within the Williamite High Command. Once it was clear that the forces around Aughrim Village had been significantly reduced, Tollemache, who like many of the senior commanders was at Ginkel’s command post awaiting further orders, turned to the Marquis de Ruvigny and asked him if he should not now order his wing of the army to attack. The Frenchman brusquely replied that as the Scotsman, Mackay, was his senior officer, and not the Englishman, he would only order the attack to be made when his superior gave him the relevant orders and not before. Seeing Tollemache’s temper flare, and anxious to avoid an open confrontation between his ranking subordinates, Mackay sent his brigade commander forward to conduct a reconnaissance of the bog and to have the Melehan sounded for depth, in order to ascertain how much of an obstacle it would be for the advancing troops. However transparent Mackay’s orders to Tollemache may seem in retrospect, in an age when personal honour was a tangible substance, they allowed both of his subordinates to withdraw from a situation which could easily have led to the issue of a challenge which could ultimately deprive the Williamite army of one or even two of its senior commanders.

From his headquarters on Urraghry Hill, Ginkel continued to survey the situation closely. He would have been forgiven if he had decided to err on the side of his natural caution and react as St Ruth fully expected him to, but perhaps he was still buoyed up by the aggressive counsel of his closest subordinates, or had uncharacteristically decided to stake all on one further throw of the dice. In any event, a number of couriers were quickly despatched bearing a flurry of orders – firstly a squadron was detached from both de Ruvigny’s and Sir John Lanier’s regiments of horse and transferred from the right flank to reinforce von Tettau and Le Forest-Suzannet on the left; and secondly, his remaining infantry – the four Anglo-Irish brigades of Mackay, Tollemache, Bellasis and Steuart – were given the order to advance across the bog and assault the hereto unengaged Jacobite infantry positions on Kilcommodan Hill, securing a bridgehead on the lower slopes which could be developed and exploited into a major attack if and when either von Tettau was successful on the left flank or if a passage could be forced across the Causeway on the right.

The instructions to the cavalry are both straightforward and understandable in that the narrow causeway across the bog could only accommodate two riders travelling abreast, and thus it made sense to alleviate a possible ‘log-jam’ by transferring a number of troops to the opposite flank, where it was still hoped that a breakthrough could be made. Opinion, however, is firmly divided as to the exact nature of Ginkel’s orders to the infantry. It is generally accepted that the troops were ordered to attack across the bog and, having gained a lodgement amongst the Jacobite positions on the lower slopes of Kilcommodan Hill, establish a defensive position which could be held pending a development on either flank. A number of commentators believe however, that, the nature of the orders notwithstanding, his actual intent was solely to order the next brigades in sequence – Bellasis and Steuart – to begin their echeloned advance towards the Jacobite positions, but that he then panicked and instead issued orders for the whole line to move forward, thereby effectively denying himself the future usage of an infantry reserve. Others are of the opinion that the order was given in the knowledge that for the plan to succeed the enemy had to be closely engaged but that given the difficult ground which first needed to be crossed, he felt that it would be counterproductive to continue to attack in echelon and that the disadvantage of terrain needed to be mitigated as soon as was practicable for fear of the assault being defeated in detail.

Of the two options cited, it would seem that the latter is the more likely as there is no evidence to the effect that either Mackay – the plan’s architect – or Tollemache, both of whom were within the immediate vicinity when the orders were given, attempted to remonstrate with Ginkel over his instructions. In addition to this, and in view of the literal impact of artillery in the mythology of the battle, one must examine the role which had been played up to this point by the cannon of both armies.

While it is true to say that the usage and deployment of artillery within late seventeenth-century armies had evolved apace with the development of the science of ballistics, the organisation of an army’s artillery train was not as professional as it would become during the latter half of the following century, and as a result the disdain of the ‘line’ officers denied it the social cachet that it would later achieve. The train itself was commanded by a Master Gunner who would have a number of gunners under his command whose task was to oversee the operation of the guns and batteries, with the weapons being served by matrosses, themselves either labourers employed to operate the cannon under the direction of the gunners or troops seconded from infantry units for the same purpose. The main difference between the two periods, however, lay in the fact that at the time of the Aughrim campaign, the artillery was still drawn by horses (or in the case of the Jacobite cannon, also by draught oxen) provided by civilian drivers and teamsters who had been hired – either for a single engagement or a whole campaign – to literally supply the muscle (whether human or horseflesh) to move the guns around the battlefield. As such they were understandably loath to place themselves in a position of real danger – often being simply contracted to drag the guns into position and then retire out of harm’s way, which would mean that especial care was needed in deploying the batteries as, once sited, they were relatively immobile. A prime example of this occurred on 6 July 1685 at the Battle of Sedgemoor when the Bishop of Winchester, who was accompanying the royal army, had to offer his carriage horses to move the artillery at a crucial point in the battle as the hired labourers had decamped almost as soon as the fighting started.

Another important factor is that even weapons of the same calibre would differ in size and weight and would thus have different characteristics – As a rough guide there were three types of gun within each calibre range: the ‘full’ cannon, which utilised a powder charge equal to the weight of shot e.g. a 4lb cannon would use an identical powder charge to fire the ball; the ‘demi’ cannon which would use a charge of approximately four-fifths that of the ‘full’ cannon, while the ‘bastard’ cannon took a charge roughly equal to two-thirds the weight of the ball.

Further factors which would affect performance would include the metal from which the cannon was made, the method of its casting, the length of the barrel – as an example, and irrespective of calibre, French cannon of ‘la vieille invention’ (and most likely the types used in Ireland) would average between 10 feet 7 inches and 11 feet 1 inch in length – and would ignite the charge from a touch-hole at the back of the chamber, whilst those of ‘la nouvelle invention’ which came into use around the 1680s were much shorter and ignited the charge through a touch-hole on the top of the chamber. As a result, the weapons’ characteristics e.g. close and maximum ranges would therefore vary accordingly.

When the Jacobite army first took the field, it had only ten light guns of French manufacture – a mixture of brass and iron guns mainly of 4lb or 5lb in calibre, one of which had to be sent back to Limerick for repair before the armies met in battle. Only capable of engaging targets at a relatively short range, and with no other real option, St Ruth deployed his few cannon conventionally, dividing them into two small batteries which were sited to protect the sectors which he deemed crucial to the defence – namely the Causeway and the Attibrasil Bridge. Conversely, with an artillery train comprising more – and heavier – cannon, Ginkel enjoyed all of the advantages over his opponent with the exception of the most crucial: the artillery of the period could generally only engage targets within line of sight, and with the main body of Jacobite troops deployed on the upper slopes of Kilcommodan Hill and both armies separated by a great expanse of boggy terrain, the Williamite gunners would be firing at extreme range – and the effect on the enemy negligible – while the Jacobite guns would be engaging the Williamite troops at virtually point-blank range. He needed, somehow, to bring his artillery closer to the enemy battle line where it could have a more tangible effect. The fact that a number of cannon were subsequently ordered to advance in the wake of the infantry can only serve to emphasise the fact that the ‘General Order’ given for both Mackay’s and Tollemache’s divisions to move into the attack was in fact a deliberate and premeditated act on the part of the Williamite commander.

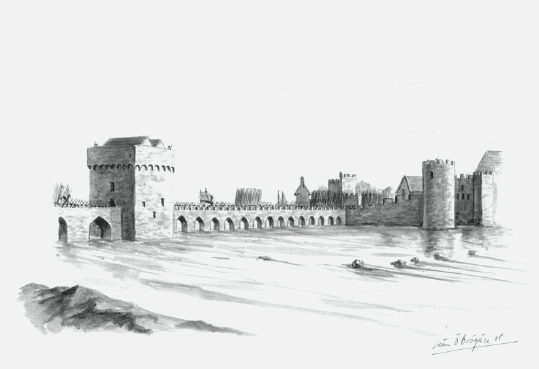

‘Marching to Destiny’ – The Jacobite army crosses the Thomond bridge at Limerick. (Seán Ó’Brógáin)

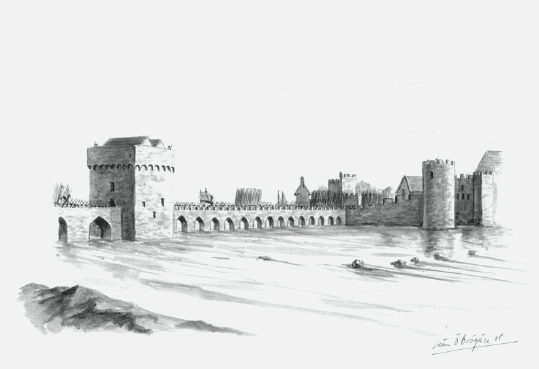

‘Into the Breach’ – The Williamite assault on English Town at Athlone. (Seán Ó’Brógáin)

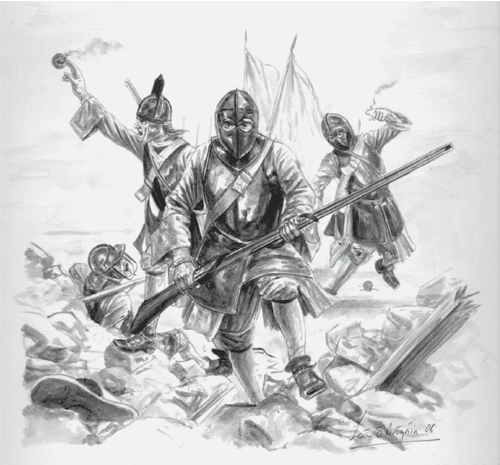

‘The Prize’ – Clanrickarde’s colours are retrieved from the Shannon by a Williamite soldier. (Seán Ó’Brógáin)

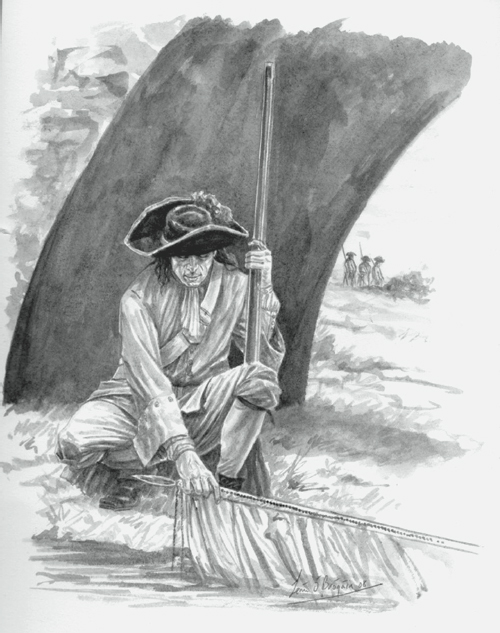

‘A Forlorn Hope’ - Sergeant Custume’s dragoons attempting to demolish the Williamite repairs to the bridge at Athlone. (Seán Ó’Brógáin)

Trooper of the Galmoy regiment, Ireland 1690. (Seán Ó’Brógáin)

Soldiers of the Dutch-Brandenburg regiment in Ireland in 1691. (Seán Ó’Brógáin, private collection)

At first glance, it would seem apparent that Ginkel was simply reinforcing failure. But with an open flank and their direct supports still bogged down in the marshy terrain and consequently unable to intervene, the situation for de la Mélonière’s Huguenots was becoming critical. Should either St Ruth or Hamilton decide to go over to even a limited offensive, then a possible Jacobite counter-attack using the declivity as a pivot, would sweep down from the hill slopes and, hitting the Frenchmen simultaneously from front and flank, would then almost certainly push them southwards along the line of the hill and into the right flank of von Tettau’s attack before any other Williamite troops could interpose themselves. The effects of such a move would potentially have spelt catastrophe for Ginkel’s forces – the Huguenot brigade would most likely have been severely mauled, if not destroyed, whilst the Danish battalions would have been undoubtedly swept up in the chaos. The only potential danger for the attackers would have been if the Jacobite commanders had been unable to maintain a tight control over their men: Sarsfield and de Tessé had already shown that the horse and dragoons could launch such manoeuvres and then still be successfully reined in to prevent an unwanted pursuit. If the infantry colonels could keep their troops in hand, and use the adverse terrain as protection from the enemy horse, it was almost certain that the Danes would be thrown back with heavy loss, and the left flank attack come to a grinding halt. In short, by adopting Mackay’s plan, Ginkel had crossed a Rubicon of sorts – the attack had now to be pressed home at all costs.

Comprising seven battalions of Anglo-Irish Foot – almost 5,000 men – and led by Mackay himself, the next line of Williamite infantry now began its advance towards the waiting Jacobites. Like much of Ginkel’s army, the majority of the troops were relatively inexperienced – the regiments of Sir Henry Bellasis, and Colonels Abraham Creighton, Thomas Erle, Charles Herbert and Henry Moore, Earl of Drogheda – many of whom had been specifically raised for service in Ireland on i April 1689, but had only arrived in the country as part of William’s army in June 1690. In addition, the division contained two veteran battalions, that of Edward Brabazon, Earl of Meath and arguably the most famous or, depending on one’s perspective, infamous regiment in the British army – the Queen Dowager’s Regiment of Foot.

Originally raised in 1661 to garrison the newly acquired possession of Tangier, this regiment had returned to England in 1684 under the command of Lt-Gen Percy Kirke, the last governor of Tangier, and were subsequently known as ‘Kirke’s Lambs’ from their regimental device of a Paschal Lamb.

Under Kirke, the regiment had gained a reputation for excessiveness during the suppression of the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685, a reputation which was more than matched by that of its commander. While Governor of Tangier it had been said of Kirke that, in his presence, the only woman whose virtue was safe was Lady Kirke, and that precisely because she was his wife. In 1688, when James offered Kirke the position of Commander in Chief of the British army, with the proviso that he join the Catholic Faith, that worthy demurred citing a tacit agreement with the Sultan of Morocco to the effect that should he leave the Anglican Church, it would only be to become a Moslem. Throughout the campaign in Ireland, Kirke’s conduct was often called into question by his peers and superiors, eventually leading to his transfer to Flanders. During the Aughrim campaign, the regiment was commanded by Lt-Colonel Henry Rowe.

Supporting Mackay’s troops were two brigades of foot under the direction of Maj-Gen Thomas Tollemache, and comprising the Anglo-Irish regiments of Richard Brewer, John Foulkes, Lord George Hamilton, Thomas St John, William Steuart, Zachariah Tiffin and Adam Loftus – Viscount Lisburn – as well as the Dutch regiment of Prince Albrecht of Brandenburg. Finally, and in effect forming a third line of attack came a battery of twelve 12lb cannon whose orders were to follow one of the tracks which traversed the waterlogged terrain, and deploy on a small hillock from which they could provide close fire support for the infantry attack in the centre and defend against any attempts to storm the causeway.

With the likely exception of the veteran English battalions and the Prince of Brandenburg’s Dutch infantry, all of whom would have been almost certainly armed with a preponderance of flintlock muskets, most of the newly raised Anglo-Irish regiments would have carried the matchlock muskets that had originally been put in storage during James’s attempted introduction of the flintlock musket as the universal weapon of the British infantryman, but which were once more put into use following the failed weapons amnesties of 28 February and 1 April 1689. Although the more modern flintlocks could be primed and if necessary left on ‘safety’ – i.e. at ‘half-cock’ – while the troops manoeuvred, the fact that the majority of the attacking force would be obliged to concentrate on keeping their matches dry while crossing the watery terrain was another factor which led to the obvious confusion in the Williamite ranks.

In order to reach the enemy positions, the two lines of infantry would have to cross several hundred yards of mostly boggy terrain – in the midst of which they would have to negotiate the River Melehan, the condition of which was at that time unknown to both Ginkel and Mackay – before they could come into contact and, at times having to wade through waist-deep sludge, they soon lost their cohesion and brigade integrity, with both formations intermingling as troops progressed at different speeds depending upon the terrain underfoot; a further complication being the several areas of ‘dead ground’ which not only concealed the advancing troops from enemy fire, but also prevented them from aligning their advance properly. In the centre of the line, a large knot of infantry soon broke away from their compatriots – Erle’s regiment, leading the advance, was followed by Brewer’s, Creighton’s and Herbert’s battalions, themselves closely supported by those of John Foulkes and William Steuart.

Some distance to Erle’s left, St John’s and Tiffin’s battalions – and presumably those of Lisburn and Brandenburg – now began to veer towards the open right flank of de la Melonière’s Huguenot brigade, not necessarily due to any direct orders to move in support of the Frenchmen, but rather due to the vagaries of geography which had led St John to find a pathway through the morass which had proven slightly easier going than other possible routes. Further to the north, and covering Erle’s right flank a further five battalions – Kirke’s, Bellasis’, the Earl of Meath’s, Gustavus Hamilton’s and Lord George Hamilton’s found themselves advancing parallel to the causeway by which the Athlone-Galway road traversed the bog.

Having initially positioned himself in the centre of the line, Mackay gave firm and explicit orders that the limit of the advance was to be to the edge of the first line of hedges at which point the attacking divisions were to adopt a defensive posture while awaiting further instructions from either himself, or from the army commander. Once he was satisfied that Erle and his colleagues had fully understood their verbal instructions, Mackay then moved northwards where he then joined Kirke’s battalion, staying with them until he had guided Rowe’s column into the defensive positions he had chosen for it, before moving back through the morass to Ginkel’s headquarters.

The confusion which the adverse and almost impossible terrain had caused the Williamite centre was not limited to the deployment and movement of the individual regiments, but also affected their command and control structure. In his memoirs, and in describing the forward movement of the brigade commanded by Georg von Hesse-Darmstadt, Mackay wrote:

‘…aussi bien que la seconde brigade de la droîte, que le Prince de Hesse tira de son poste par je ne sais par quel ordre…’

Which translates as

‘…as well as the second brigade of the right, which the Prince of Hesse advanced from its’ position – under whose orders I do not know…’

The confusion derives from the interpretation of the author, John Mackay, who in his biography of his namesake has rendered the translation of the last phrase as being ‘the Prince of Hesse had brought forward without orders’, the author’s assertion, in effect, being that the troops were moved without instruction from a senior officer.

With hindsight, the confusion is easily reconciled – the brigade in question did indeed move forward and while Mackay correctly states that he was unaware who gave the order for Hesse-Darmstadt to advance, the next senior officer in the chain of command was actually Tollemache, who had command of the second division, and it would therefore be quite reasonable to assume that any such orders would have emanated from him, rather than from his superior officer who was busy personally directing the movement of the two leading brigades, which were his own direct responsibility.

Behind the slowly moving line of infantrymen, the artillery battery picked its way carefully forward, following a narrow track towards a small hillock which, rising from the Melehan Valley, would allow them to engage the Jacobite positions from a position of relative safety. Rather than the single echeloned attack called for by Mackay’s plan, and envisaged by Ginkel, the stage was now set for a series of individual contests which would dictate the outcome of the battle.

Along the southern slopes of Kilcommodan Hill, von Tettau’s attack had by and large run out of steam. The troops were still in contact, and with both sides claiming local succcesses a clear advantage was both elusive and illusory. The Danish foot were unable to create a breach in the enemy defences through which the left wing cavalry, with its superior numbers, could exploit, while the Jacobites limited themselves to a series of sharp counter-attacks which left both sides bloodied. This relative stalemate was extended northwards to the ranks of de la Mélonière’s brigade where one regiment was trapped under enemy fire while the remaining battalions were trying to link up with Thomas St John’s infantry which were slowly freeing themselves from the watery grip of the bog.

This timely reinforcement, along with the arrival of Hesse-Darmstadt’s brigade which completed the line had by now strengthened the Williamite left-centre to such a degree that any Jacobite threat in this area had been effectively neutralised, and the troops began to engage the enemy positions.

In the centre of the Williamite line, the attack developed almost by accident: More by luck than judgement, Erle’s battalion had crossed the swamp at virtually its narrowest point, eventually emerging onto firm ground where the hedge line – and thus the Irish defences – was at its closest.

As St Ruth had ordered, the Irish detachments manning the hedges allowed the attacking forces to come in to within almost point-blank range, remaining in position until the last possible moment before revealing themselves. As the advancing enemy units were still forming up having reached firm ground, each of the Jacobite ranks delivered a crashing volley and, whilst the redcoats were still reacting to the sudden onslaught, quickly retired directly backwards to the next hedge line and the next series of prepared positions.

The Rev. George Story perfectly describes the surprise and confusion engendered by St Ruth’s tactics:

‘Col. St.John, Col. Tiffin, Lord George Hamilton, the French and several other Regiments, were marching over below upon the same Bogg. The Irish in the mean Time, laid so close in their Ditches that several were doubtful whther they had any Men at that place or not: but they were convinced of it at last; for no sooner were the French got within twenty Yards, or less, of the Ditches, but the Irish fired most furiously upon them, which our Men as bravely sustained, and presed forwards, tho they could scarcely see one another for Smoak’.

Once the Williamite officers had marshalled their troops, and having delivered their own volley against the pall of smoke which by now hung over the ground to their front, they launched their own attack only to find the enemy position vacant – ahead of them the retreating Jacobites easily outdistancing Erle’s men who were still attempting to negotiate the hedges. With Erle and his peers now realising that Mackay’s orders would be tantamount to a death sentence and that the only way out of their predicament was to press forward, the deadly formula was repeated again and again as the Anglo-Irish battalions were drawn piecemeal upslope by the Parthian tactics of the retreating enemy.

In his memoirs, Richard Kane continues, eloquently capturing the frustration of the advancing troops:

‘When we, on the right, attacked them, they gave us their fire and away they ran to the next ditches and we, scrambling over the first ditch made after them to the next from where they gave us another scattering of fire and away they ran to other ditches behind them, we still pursuing them from one ditch to another until we had drove them out of four or five rows of these ditches into an open plain where was some of their horse drawn up. Here in climbing these ditches and still following them from one to another, no one could imagine that we could possibly keep our order, and here in this hurry there was no less than six battalions so intermingled together that we were at a loss what to do.’

Story also gives a clear description of Erle’s attack:

‘Colonel Earl, Colonel Herbert, Colonel Creighton and Colonel Brewer’s Regiments went over at the narrowest Place, where the Hedges on the Enemies side, run furthest into the Bogg. These four Regiments were ordered to march to the lowest of the Ditches, adjoining to the Side of the Bogg, and there to post themselves, till our Horse could come about by Aghrim Castle, and sustain them, and till the other Foot had marched over the Bogg below, where it was broader, and were sustained by Col. Foulk’s and Brigadier Stuart’s. Col. Earl advanced with his Regiment, and the Rest after him, over the Bogg, and a Rivulet that ran through it, being most of them up to their middles in mud and water. The Irish, at their near Approach to the Ditches, fired upon them, but our Men contemning all Disadvantages, advanced immediately to the lowest Hedges, and beat the Irish from thence. The Enemy, however, did not retreat far, but posted themselves in the next Ditches before us: which our Men seeing, and disdaining to suffer their Lodging so near us, they would needs beat them from thence also, and so from one Hedge to another, till they got very nigh the Enemies main Battel’.

Drawn on by these Fabian tactics, the red-coated infantry now began to pull away from their supporting battalions, who were themselves only now emerging onto dry ground and reforming, thrusting forward in a narrow wedge. Gradually Erle’s battalion lost all pretence of formation, pushing ever further uphill into the Jacobite defences, and as the enemy fire intensified the colonel began to exhort his men to even greater efforts crying ‘There is no way off but to be brave!’ At the base of Kilcommodan Hill, Charles Herbert’s infantry began to follow Erle’s trail, whilst colonels Brewer and Creighton contented themselves with holding a bridgehead on the lower slopes of the hill.

The situation was almost mirrored on the extreme right of the line, where Mackay found himself potentially isolated with but a portion of his command. In fulfilment of his plan, he ordered Lt-Colonel Rowe of Kirke’s regiment to advance past the base of the hill and seize a cornfield which lay beyond the end of the causeway, and due south of Aughrim Castle, from which position his men would not only be able to cover and support an attack on the narrow defile by the right wing cavalry, but they themselves would also be able to engage the enemy at range from a relatively secure position.

The sole object of concern for Rowe’s ad hoc brigade was the presence of the small Jacobite battery which had been deployed to cover the causeway, but which was now able to engage his troops at a relatively short range – the sooner the supporting twelve-pounders were dragged into position and cleared for action, the sooner the situation could be stabilised, and the next phase of the plan put into action.

So far, Ginkel and Mackay had more than sufficient reason to be satisfied with developments – their initial feint attack on the Jacobite left had succeeded to the extent that, in order to reinforce the threatened position, St Ruth had been obliged to strip troops from the sectors against which the Williamite main effort was eventually to be thrown. Secondly, the objective of establishing a lodgement within the enemy lines from which the army had the option of either launching a heavy attack or reverting to the tactical defensive had been largely achieved while, with the exception of the transfer of a number of units to reinforce the left flank, the army’s right wing cavalry – now comprising six regiments of horse and two of dragoons – remained available as a sizeable reserve. The only disappointment was Erle’s unwanted progress in the centre, a movement which, in the absence of both Mackay, who was with Rowe’s brigade, and Tollemache, who was still negotiating his passage across the bog, for good or ill, would have to be allowed to run its course.

The view from the Jacobite headquarters on the top of Kilcommodan Hill was equally optimistic: despite any personal antagonism between St Ruth and Patrick Sarsfield, the Frenchman had to admit that the Irishman – along with de Tessé – had handled his troops consummately. He had stopped the main enemy thrust dead in its tracks, holding it to such a degree that Ginkel had been forced to strip valuable troops from his own right wing in order to reinforce and maintain the momentum of the attack on the southern approaches to Kilcommodan Hill. The remainder of the Williamite right flank remained stationary, a sure sign that his opponent viewed the Jacobite left as an exceptionally tough proposition that would be best left alone.

All that remained now was the contest in the centre of the battlefield, and the reliability of St Ruth’s tactics could be seen not only in the ruptured enemy advance, but also in the ranks of enemy dead that marked each of the successive defensive lines from which his forward detachments had withdrawn.

With the Williamite battalions strung out and lacking cohesion, all that was required was a sharp counter-attack to throw the enemy back the way they had come. We know that St Ruth maintained the utmost confidence in a Jacobite victory until the end and perhaps, even as he dictated the orders instructing Sarsfield, Dorrington and Hamilton to advance and go over to the offensive, he could see – in his mind’s eye – the Williamites in full retreat back to Dublin, being harried every step of the way by vengeful Jacobite horsemen. But it is doubtful if Sarsfield and de Tessé actually received the orders instructing them to launch a counter-attack as, by the time the St Ruth’s courier arrived, they were once more engaged with the troops of von Tettau and La Forest-Suzannet who, following the arrival of reinforcements had made another attempt to force a passage through the Jacobite lines and into the enemy’s rear.

As St Ruth had anticipated in his army deployment, it was the defenders’ advantage in terrain that had proved to be the deciding factor in this contest, rather than superiority in numbers, and once again the action on the southern slopes of Kilcommodan Hill reverted back to a stalemate with both sides pulling back to lick their wounds. Convinced that they would not be able to dislodge the Irish troops from their positions, the Williamite generals reverted to their previous posture of being content merely to hold the enemy right wing in place.

Buoyed by the fervour of St Ruth’s earlier speech, even if the vast majority of them were unable to understand the words, the Jacobite foot regiments in the centre reacted to their change in orders with an enthusiasm that reflected their frustration at their having been held in check for so long. From the ‘post of honour’ on the extreme right of their brigade and led by their regimental chaplain, Dr Alexius Stafford, Dean of Christ Church Cathedral in Dublin, came the two battalions of King James’ Foot Guards reputedly almost two thousand strong. In red coats lined and faced in blue, and with the Cross of St George surmounted by the Royal Standard snapping in the wind above their well-ordered ranks, the guardsmen gave a shout and advanced towards the enemy.

The cry was echoed the length of the Jacobite line as it surged forward, hitting the Williamite troops with an almost irresistible force – caught in the open, and hit both from the front and flanks, Erle’s battalion was swamped by the Irish infantry, many of the men going down under a sea of pikes and clubbed muskets. As his regiment disintegrated, Erle was wounded and taken prisoner, along with a number of his men including Captains Bingham and Gooking, two of his company commanders. The tide swept onward, effortlessly overwhelming Herbert’s regiment, whose commander was also captured. With several hundred of their comrades rushing towards them, and with Gordon O’Neill’s Ulstermen in close pursuit, the battalions of Abraham Creighton and Richard Brewer were also unable to hold their ground, and were caught up in the infectious retreat which now began to threaten the whole Williamite centre.

For the infantry now labouring to come into formation at the base of Kilcommodan Hill, just as for their commanding general some distance to their rear on Urraghry Hill, the Jacobite counter-attack came as yet another unwelcome surprise – ever since the Siege of Derry, and the battles of Newtownbutler and the Boyne, the Williamite forces had been virtually indoctrinated with the mantra that whilst the Irish horse were worthy adversaries, deserving of both caution and respect, their foot would not stand in open combat; as long as they themselves could maintain their own cohesion and discipline, the enemy would be simply driven from the field like sheep. Yet here, in front of their very eyes, the Irish had not only stood and defended their outlying positions with a hereto unanticipated skill and tenacity, but were now charging downhill intent on coming to grips with the foe.

The Jacobite advance in the centre was in no way as ordered as would normally be imagined. This was not due only to a lack of training in a number of the regiments, but also to the enclosures which had so admirably suited St Ruth’s tactics for dealing with the initial Williamite attack. These now acted to the detriment of his troops causing them to break formation, the movement more resembling a ‘rush to contact’ rather than an ordered charge, as the men plunged downhill as companies rather than as battalions.

Suddenly, and against all prior expectation forced on to the defensive, the Williamite battalions discharged a ragged volley before the two sides crashed together, with Dr.Stafford being mortally wounded as he ran downhill, leading the Foot Guards toward the enemy. The Jacobite line staggered slightly but its momentum carried it into the enemy lines, partially taking the leading battalion of Georg von Hesse-Darmstadt’s brigade in the flank as it tried to conform to the rest of an ad hoc defensive line which, although it buckled under the assault, held intact. A fierce mêlée now developed, with the bulk of the Irish foot preferring to use clubbed weapons although some units, such as the Foot Guards, still charged the enemy ranks ‘à la baionette’. As if to add insult to injury, with von Tettau’s troops no longer advancing, the Jacobite artillery which had been placed to cover the Attibrassil Bridge now began to open fire on the rearward elements of the enemy line.

To the north, the situation was completely different. With their cohesion completely shattered and many senior officers either casualties, prisoners or missing, the four battalions of Erle, Herbert, Brewer and Creighton were themselves – ironically – being herded like sheep. The Jacobite infantry pushed them ever further back into the bog, passing over the hillock upon which the Williamite gunners forlornly attempted to deploy their pieces before they too were overrun by Gordon O’Neill’s regiment and caught up in the rout. The carnage in this area was particularly severe, and although it has been estimated that up to a third of Ginkel’s forces committed to the central attack would become casualties, the majority of those who fell did so in this sector.

On the extreme right of the Williamite centre, the infantry that had been so meticulously placed by Mackay were faring better than their comrades in arms. Judging from Mackay’s own account, it would appear that the brigade occupied a number of cornfields and gardens in a salient south of the causeway. The Earl of Meath’s regiment was deployed on the left of the position, with Sir Henry Bellasis’ and Lord George Hamilton’s battalions occupying the ‘bow’ of the formation, facing off against the main Jacobite body. Rowe’s troops held the right and entered into a brisk firefight with the enemy positions around Aughrim village and Aughrim Castle.

From his command post on Urraghry Hill, Ginkel could see the control of the battle, and indeed its outcome, gradually slipping away from him. The limited attacks around the Attibrassil Bridge had indeed drawn enemy troops away from the area in which he and Mackay had decided to launch the decisive attack, but this success would be less than illusory if the army’s centre were to collapse like a house of cards. The only sign of any promise was that Rowe’s battalions were firmly ensconced amongst the fields on the northern slopes of Kilcommodan Hill, near to where the Causeway exits the bog and would be able to lend much-needed fire support to cover any attempt by the right-wing horse to force a passage through to the village of Aughrim.

It was the crucial point of the battle, and the outcome hung finely in the balance. The attack on the Jacobite right flank had, despite reinforcement, stalled once again and now, in the centre, one-third of the Williamite infantry was in full retreat, with seemingly no likelihood of their being rallied. The remainder were either being slowly pushed back towards the bog or were trapped in a defensive position which was relatively secure as long as the troops remained in position behind the walls and hedges.

Even at the moment when he was most susceptible to his anxieties, Fate was now to smile upon Ginkel; uncharacteristically for him, Tollemache had not crossed the bog at the head of his brigade, but had been forced by circumstance to move to its rear in an attempt to push his straggling units forward so that the formation would maintain its cohesion and integrity before being committed to action. He now formed these two battalions as a breakwater to slow the rout and give him the chance to rally the broken units and throw them into a desperate counter-attack in an attempt to salvage the situation.

Typically, the Jacobite colonels had been unable to counter the enthusiasm of their men to pursue an apparently beaten foe and in scattered groups the swiftest of the Irishmen now found themselves faced by a steady line of Williamite redcoats led by the battalions of John Foulkes and William Steuart. Again the fortunes of war reversed themselves, and some two or three hundred of the pursuers became casualties before they could extricate themselves and fall back upon the first line of hedgerows upon which Dorrington and Hamilton now anchored the Jacobite line. Again, St Ruth’s instincts had been proven correct, as his riposte to Mackay’s advance had almost broken the enemy centre and won the battle for him at a single stroke – only the fortuitous presence of Tollemache and his conversion of retreat into counter-attack had halted the rot which had threatened the whole army.