CHAPTER 15 In Every Young Man’s Life…

Eve’s Hollywood was released in March 1974.

The book is a series of autobiographical sketches arranged more or less chronologically. A loose memoir is what I would call it. “The history of an adventuress,” is what Eve did call it. Eve’s Hollywood is not a mature or disciplined work. You’ll notice, every so often, a slight strain in the prose, the odd patch of tangled grammar. Certain pieces, you don’t know what they’re doing there, and none reach the level of “The Sheik,” the collection’s high-water mark. And yet, riffs that surprise and delight abound.

For example, Eve on watching her classmates dance the Choke in the gymnasium of Le Conte Junior High:

The Pachucos were what we called kids who spoke with Mexican accents whether they were Mexican or not and who lived real lives… They’d been expelled from school for carrying knives, they stole cars, fought, and their style of dance, the Choke, was so abandoned in elegance it made you limp with envy… The Choke looked like a completely Apache, deadly version of the jitterbug only you never thought of the jitterbug when you watched kids doing the Choke. There was no swing in the Choke… It was Pachuco, police-record, L.A. flamenco dancing.

Or Eve on vamping at the bar of the Garden of Allah hotel with her friend Holly, called Sally:

[Sally and I] were in Café Society at night and school in the daytime. We were both virgins, too, as we drank in the Garden of Allah bar with fake IDs… We had no more business suddenly finding ourselves in [this] jaded, fast world than we did on the freeway on foot. Things whihhissshed past us dangerously.

And then there’s the book’s most surprising and delightful riff of all, which isn’t, properly speaking, a riff or even in the book qua book; is in the book’s dedication (more on that dedication in a moment):

And to the Didion-Dunnes for having to be who I’m not.

A line that is, on first reading, a butter-up of Joan; on second reading, a put-down of Joan; on every reading thereafter, either or both, depending on your frame of mind. (FYI: I’m ignoring Dunne on purpose here because he failed to capture Eve’s imagination—“I don’t like the way [he] writes,” she noted in her journal, entry dated January 13, 1970—and I suspect she only lumped him and Joan together to needle Joan.)

Eve’s Hollywood, overstuffed as it is, doesn’t seem soft or flabby, but rather baby-fat voluptuous, the extra weight appealing, giving you something to grab, to squeeze, to pinch. If the book has a flaw—non-niggling, I mean—it’s connected to identity: L.A.’s and Eve’s, one and the same in her view.

Eve takes L.A. personally. And that New Yorkers think they have the right to look down their noses at it galls. She defends her city as she’d never defend herself. Though that’s really what she’s doing when she squares off against the “stupid asshole creep[s]” and “provincial dope[s]” who miss the “true secrets of Los Angeles [that] flourish everywhere” because they’re so determined to believe that something with obvious superficial charms cannot also possess subtle deep ones. In fact, Eve, with the title of her opening piece, “Daughters of the Wasteland,” is alluding to that classic New York knock on L.A. (“cultural wasteland”), as well as to Joan (“Notes from a Native Daughter” is among the better-known pieces in Slouching Towards Bethlehem). All she has to do to repudiate the wasteland charge is list the people who walked through the front door of her childhood home: Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Dahl, et al.

So, Eve’s parents and the friends of Eve’s parents confer legitimacy on L.A. Who, though, would confer it on Eve? She could confer it on herself, of course, sheerly through the force and freshness of her voice and sensibility and observations. Only she doesn’t trust these things yet, believe they’re enough to compel attention.

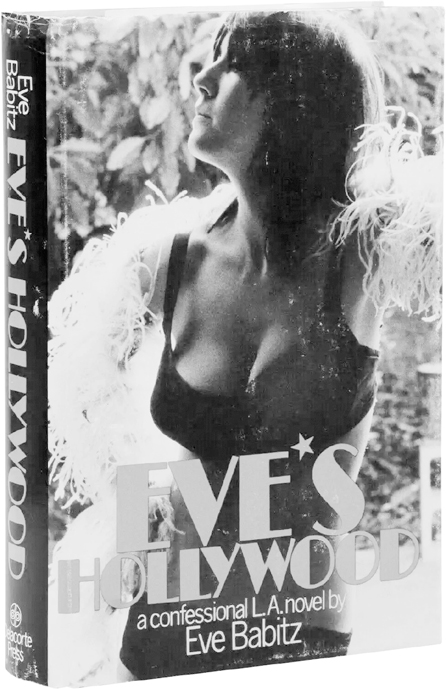

Which is why the cover photo taken by Annie Leibovitz: Eve in a white boa and black bikini, face in movie-star profile, cleavage deeper than the San Fernando Valley.

Eve in starlet mode for the cover of Eve’s Hollywood, shot by Annie Leibovitz.

Which is why the blurb on the inside flap that could be the tagline for an exploitation picture: “In every young man’s life there is an Eve Babitz. It is usually Eve.” Earl McGrath’s words, but Eve didn’t know this at the time, so attributed them to “Anonymous.” (“They won’t tell me who said that though I’ve begged and pleaded,” she told Walter Hopps in a 1972 letter.)

And which is why the name-dropping, incessant and unremitting. The dedication page is, in my first-edition copy, eight pages. Eve thanks the greats currently in her life: Ahmet Ertegun (“the record company president of my choice”), Stephen Stills (“[for] letting me do the art part”), and Steve Martin (“the car”). The greats formerly in her life: Marcel Duchamp (“who beat me at his own game”), Jim Morrison (“running guns on Rimbaud’s footsteps”), and Joseph Cornell (“A Real Artist”). The greats she wishes were in her life: Paul Butterfield (“over yonder’s wall”), Andy Warhol (“who I’d do anything for if only [he’d] pay”), and Pauline Kael (“who we discovered on KPFA and whose sentences don’t parse either”). The style is ultra-insider: half Oscar acceptance speech, half yearbook inscription–ese, and entirely unintelligible to the average reader.

I’ll decode for you.

The car is a 1965 VW, a present to Eve from Steve Martin. (It’s the one that broke down while she was living in San Francisco with Grover Lewis.) “Linda Ronstadt was his girlfriend and I was his girlfriend and we were both doing him wrong,” she said.

Joseph Cornell was Eve’s other certified-genius pen pal. “I wrote him a letter after I went to that show in New York with Carol [Granison]. He wrote me back asking for a pinup picture. I knew what he meant but I couldn’t give him one. I loved him too much. I just wanted to be his fan.”

Pauline Kael was the movie critic for KPFA, a listener-supported radio station in Berkeley, before she was the movie critic for the New Yorker. “I was die-hard for Pauline. She was in love with movies the way I was in love with L.A. She’d drive everyone crazy with her opinions. But for me it was simple—she was right and everyone else was wrong.”

The implicit message of the dedication page is that if Eve’s famous friends think she’s all right, so should you. She’s unsure of herself, and this lack of sureness is why Eve’s Hollywood takes a while to get going. It’s not until “The Choke,” the eighth piece, the one about the sexy Pachucos, that she stops trying to throw stardust in the reader’s eyes, dazzle or blind. At last, she breaks out of Sol and Mae’s social circle, and her own—for her, vicious circles—to talk about her life, how she experiences it, looks at it, jokes about it. The joking is key. “Los Angeles laughter is the most extreme form of American laughter,” wrote poet Peter Schjeldahl. “Such laughter is apparently uncaused, childlike, irresponsible, gratuitous[,] a constant eddy of mirth that is the opposite of irony.” L.A. laughter is, I’d argue, the soundtrack to Eve’s Hollywood.

That soundtrack kicks in right around the one-quarter mark. All of a sudden, the book has pace, control, edge, interest. And the stories it’s telling become more and more amusing, more and more moving, more and more involving. Become exactly the stories you want to hear.

Eve’s Hollywood was mostly ignored by reviewers. That wouldn’t have happened, I’m convinced, if Eve had allowed Joan to give it her imprimatur. (“I fired Joan” was thus a double homicide: Eve, with those words, killing Joan, but also whatever chance her book might have had critically.) And it didn’t fly off shelves either. “It sold, like, two copies,” said Eve. “I mean, nobody in L.A. read it. Well, except for Larry Dietz.”

Larry Dietz, a journalist and editor, a semi-friend of Eve’s, wrote about the book for the Los Angeles Times. In his assessment, Dietz posits himself as the stern yet loving schoolmaster, Eve as the showoffy little girl in need of a reprimand. He chides her for insufficiently cultivating her gifts: “To deny the full range of [your] talent because you don’t want to work on developing it is not only to diminish yourself, but also all of us who could have been enriched by it.” And for failing to live up to the shining example set by Joan Didion: “Play It as It Lays—a book so cruelly accurate that it made Nathaniel West look like Shecky Greene.” (Dietz, incidentally, spells Nathanael N-A-T-H-A-N-I-E-L. Some schoolmaster.) He ends with a direct address to the reader: “If you don’t mind some sloppy and self-indulgent writing, you’ll be rewarded with four or five chunks of good work.”

Dietz’s disloyalty irritated Eve but did not surprise her. “The main thing about Larry was that he was a twat,” she said.

Still, Eve’s Hollywood, low sales figures and twat opinions notwithstanding, changed things for her. No longer was she a girl-about-town with a dubious reputation, or an artist with a sideline in rock-’n’-rollers instead of a gallery. She was now a writer with a book to her name.

And with a new identity came a new scene.