CHAPTER 22 Beyond Squalid Overboogie

Eve didn’t just come home to Hollywood. She came home home, home to her parents’ house at 1955 North Wilton Place. In the backyard was a small stand-alone structure: her digs.

Bonna Newman, assistant to Fred Roos, visited regularly. “It was a single room,” said Newman. “In the corner was a bed. And maybe a hot plate on the counter. But no shower. Definitely no toilet. If you needed to pee—and to me this seemed wildly bohemian and romantic and writerly—you went out back and squatted in the grass.”

Available to Eve when she didn’t feel like squatting was the bathroom on the first floor of the main house. Only she used it sparingly so as to avoid run-ins with the other person then living on the Wilton Place property: a man named Sorenson.

To explain who Sorenson is, I’m going to have to tell the story of Eve’s childhood, which was also, of course, Mirandi’s childhood. The same childhood, radically different experiences of that childhood.

Now, if you listened to Eve, you’d think their childhood was out of a fairy tale. For parents, the brilliant Sol and the magnetic Mae. For godparents, Igor and Vera Stravinsky, better than fairy godparents because the Stravinskys’ magic wasn’t the hocus-pocus kind. And the family house on Cheremoya, which looked like any other from the outside, a Southern California two-story Craftsman, was, on the inside, something rare and wondrous: the lemons Mae had picked that morning, arranged in bowls (Mae preferred lemons in bowls to flowers in vases), scenting the air; the blues records Sol had spinning on the turntable (Sol preferred Bessie Smith to Billie Holiday, dirty Bessie Smith to regular) scenting the air, too. It was a place where nothing bad could ever happen. Was, in short, charmed.

If you listened to Mirandi, you’d also think their childhood was out of a fairy tale. But bad things happen all the time in fairy tales, which, as every little boy and girl knows, are really horror stories in disguise. Sol and Mae, while doting parents, weren’t always mindful ones. They could get distracted—by each other, by their art, by the art of their lives. This was less of a problem for Eve, self-reliant by nature, plus fiercely self-preoccupied. “Eve was not easy,” said Mirandi. “She was like, ‘Get lost. I’m reading.’ She’d only put her book down for people who were really interesting—Lucy Herrmann or Edward James or Vera. Otherwise, forget it.”

Mirandi’s personality was softer, gentler. She was undefended in a way that Eve was not. She needed defending, in fact, from Eve. When she was a baby, Eve threw an electric heater into her crib. At the last second, Eve called for Mae, and she was saved. Her left hand, though, was incinerated, and required extensive plastic surgery. “To this day I can remember how surprised I was when I realized that she was actually on fire and that it hurt and that I hadn’t meant to hurt her,” wrote Eve, “I’d only meant to dispose of her permanently.”

In fairy tales, princesses and monsters abound. Mirandi, her affect so like that of the former—delicate, tender, pure of heart—had to contend with more than her share of the latter, Eve not the only she faced, Eve not even the only she faced in the house. “Daddy needed to be careful of his hands, and so he couldn’t do much around the house, and so Mother went down to Skid Row and picked up this fixit guy,” said Mirandi. “Mr. Sorenson. He lived in a shed out back. Oh, Mr. Sorenson.”

Sorenson, dirty, derelict, without family or friends, embodies so many clichés about men who prey on children that he’s practically an allegorical figure. When Mirandi was five, he started coming to her room on Saturday nights, invading first her ears—“He wore clogs, I could hear the sound they made on the floor”—then her nose—“He always smelled like apricot brandy”—then her doorway, where he would stand and masturbate—“I was too young to know what he was doing, but that’s what he was doing.” When she was seven, and taking zither lessons from him in his shed, he raped her orally, this after failing to rape a neighbor boy anally while she looked on in horror. “Mr. Sorenson said he’d put one of my kittens into a sack and beat it to death with his shovel if I told anybody, so I didn’t. Not even Mother.”

Fortunately, Mirandi, in addition to being a waif and imperiled, was also a plucky kid and resilient. She said nothing to Mae about what Sorenson had done, but she did tell Mae she hated him. And Mae, baffled, let her quit the zither lessons, which got her out of his shed and clutches.

Sorenson’s preference was plainly for prepubescents, but he made do with an of-age Eve when the opportunity presented itself. “It was right before the family left for Europe,” said Mirandi. “Evie had just turned eighteen. She’d been out that night with Brian, and she’d been, you know, with Brian—she was still wearing her diaphragm—and she’d been drinking heavily. She snuck in through the window and passed out in her bed. Mr. Sorenson came in after her. She thought it was Brian and so she participated in the sex until she realized it wasn’t Brian.”

Eve woke up in the morning confused. She knew something had been done to her, but she wasn’t sure what or by whom. “When Eve told me about it,” said Laurie, “she told me that it was some guy she knew from Hollywood High, Wolf Santoro, Mamie Van Doren’s boyfriend. She said he’d climbed through the window and fucked her. You know, consensually.”

And then Mae made a discovery. “Mother found a clog footprint outside Eve’s window,” said Mirandi. “And Eve remembered the smell—that apricot-brandy smell. Mother told Eve not to tell Daddy. Or me. But of course I found out in about twelve minutes. Eve told me on the plane ride to France. I just started throwing up and couldn’t stop.”

For Eve, there seems to have been a break in the chain of cause and effect with regards to the Sorenson rape. Meaning, I don’t think it had much of an effect. (The only rape she mentions in any of her letters is the near rape that occurred in New York City in 1966.) Her behavior before it and after it strikes me as consistent, of a piece. Maybe she was able to brush it off because she retained no clear memory of it. Or maybe she was able to brush it off because it happened to her not as a child but as a young woman, when she’d already had experiences with men and so the experience with Sorenson wasn’t formative. Or maybe she was able to brush it off because it was her temperament to ignore or reject that which wasn’t in her interest to notice or accept. In any case, it scarcely disrupted her flow or emotional reality.

For Mirandi, on the other hand, the effect of the Sorenson rape was profound, woeful. “I started lying. And I’d steal from the local five-and-ten. I didn’t need to steal. Mother always gave me money for comics and candy and things like that. But it made me feel good to steal because it went with my image of myself—a bad girl disguised as a good girl.”

Shortly before Eve returned to Wilton Place, Mae received a call. “It was Mr. Sorenson,” said Mirandi. “He knew he was sick. A heart condition. And he knew that somebody had to take care of him, and that it was going to be Mother. And—and this is very strange—it was Mother who was on his bank account. He was so cheap that he’d held on to every penny of his social security, so he had something like eighty thousand dollars socked away. And Mother had her eye on that money. Now, Mother didn’t know what Mr. Sorenson had done to me. I didn’t tell her until much, much later—in the early nineties when I’d left rock ’n’ roll, left concert promotion, and was sober and studying to be a therapist. And when I did tell her, she was desperately miserable about it. But she said something to me I’ll never forget. She said, ‘Well, I murdered him for Eve, so I guess I murdered him for you, too.’ My jaw dropped to the absolute floor because, up until then, she’d been in complete denial. I mean, when she and Dad came back from Europe, Mr. Sorenson started living in their house again, the house on Bronson. I guess she’d managed to convince herself that Eve was loaded and imagined the rape. But at Wilton Place, she confronted him. She said, ‘You’re going to die in hell for what you did.’ And he knew he deserved it. That’s why he left her the money, I believe. So, what Mother did is, she baked him. She stuck him in a stuffy trailer in the backyard, and it was summer, and that trailer was like a sweatbox. It got so hot, and he couldn’t move or get out of bed with his bad heart, and she knew he couldn’t, and she let him die.”

Mirandi told me this story while we were on the phone. We’d been going over, line by line, Eve’s 1977 letter to Joseph Heller. Had reached the litany of hardships Eve was living with but not writing about, including “my grandma dying of cancer next door.” I read those words out loud and, suddenly, a memory dislodged itself in Mirandi’s brain: Sorenson moving into Wilton Place after Agnes’s death, Mae taking her revenge on him for atrocities committed decades before.

Mirandi finished talking, and I don’t think I spoke for a minute at least. The scene between Sorenson and Mae was so awful and so thrilling, so thrilling in its awfulness. It was an American Crime and Punishment. Crime and Punishment if it were written by a pulp novelist—Jim Thompson or James M. Cain. The lurid lyricism and filthy-animal behavior were pure Thompson, the final cheaply ironic twist pure Cain: Mae, with her gentle manners and poetical sweetness of disposition, a stone-cold killer.

As soon as Mirandi and I hung up, I called Laurie, relayed to her the conversation I’d just had. When I was done, she repeated the word, “No,” five or six times in rapid succession, then sighed heavily. “Okay, Lili, Mirandi’s story about Mae cooking Sorenson—I just don’t think it’s true. When it came to caring for people, Mae was a fucking saint. I used to call her the foul-weather friend.”

“But don’t you think it’s suspicious that he died on her property in the middle of a heatwave?” I said.

“No, not really. Sorenson was the old family retainer, and he was dying, and Mae didn’t want him dying alone. He died on her property because that’s where he died. The fact that it was hot summertime is neither here nor there.”

Now it was my turn to sigh. “I should’ve known the story was too good to be true,” I said, trying to hide my real disappointment behind the pretense of it.

Laurie made a shrugging noise.

“Well,” I said, “do you think Mirandi thinks the story is true?”

“Oh, Mirandi more than thinks the story is true, Mirandi needs the story to be true. She needs Mae to have made Sorenson pay for what he did to her. But I know that my mother never wanted to make any of the men who did things to me pay. I was molested when I was four by the janitor in my nursery school. He put his penis against my leg and came down my leg. I didn’t know what he was doing. I thought he was peeing on me and that it was disgusting. And my mother took me out of the school because the people there didn’t believe me. What my mother told them was that the janitor needed psychiatric help. That was her reaction—to get the guy a doctor. She wasn’t looking to retaliate, and neither was Mae. Women like my mother and Mae, women of that generation, they just accepted that men did things like that sometimes, and you either put up with it or you dealt with it in whatever way you could.”

“Why couldn’t Mirandi just be angry with Mae?”

“Mirandi talks a lot about how abusive Eve was to her when they were little. And Eve was abusive to her. But when Mirandi would go to Mae, Mae would say, ‘Toughen up.’ And later on, when Sol got those grants, Mae pulled Mirandi out of high school. That’s a terrible thing to do to a kid. Mae loved Eve and Mirandi. She loved Sol more, though. And she felt that going to Europe was something Sol needed. And then there’s Sorenson. Sorenson was a creep, a total creep, but Mae refused to see it because she wanted to have a handyman around. Mirandi was enormously resentful about all this, and I don’t blame her. So, yeah, that’s what I think is going on with the Mae-cooking-Sorenson story. I think Mirandi invented it to make Mae the mother she would’ve liked Mae to have been.”

“Is it possible,” I said, picking my words slowly and with care, “that Mae let Mirandi think she killed Sorenson so that—”

Laurie interrupted me, impatient. “No.”

“But it could have happened.”

“Not in my opinion, okay?” And when I didn’t respond, “You just said that what Mirandi told you was too good to be true, and it is.”

I nodded. But not immediately or definitively. Nodded hesitantly, reluctantly.

Laurie groaned. “What’s wrong?” she said.

“Well,” I said, “what Mirandi told me and what you’re telling me are in direct conflict. I’m trying to figure out a way to reconcile the two.”

“Then you’re wasting your time. The two can’t be reconciled.”

“But—” I started.

“No, they can’t be.”

“So what am I supposed to do?”

“It’s simple.”

“It is?” I said.

“Yeah, tell both versions—Mirandi’s and mine. Let the reader decide.”

Which is exactly what I’m doing, Reader: letting you decide.

If no longer having to share a washcloth or toothpaste tube with the man who’d forced himself on her when she was an unconscious teenager was a relief to Eve, she didn’t show it. Maybe she was incapable of showing it at this point. “Eve was as off the deep end with the coke at Mother’s as she was at Femmy’s,” said Mirandi. “She was drinking, taking pills—Valium mainly. She was just getting sloppier and sloppier, sloshier and sloshier.”

So sloppy and sloshy that she nearly set herself on fire. “I went to spend the night with Eve when she first moved into that garage apartment behind her folks’ house,” said Paul. “I got there and her bed was a bed of charcoal. She’d thrown a fur coat I’d given her over a space heater at the base of the bed and it caught fire. She would have died because she was dead drunk, but Mae saw it or smelled it and threw water on it, and Eve was okay. I was horrified by the bed. Eve was pissed I’d noticed.”

Eve was avoiding that bed even when it wasn’t aflame. A recollection of Bonna Newman’s:

I’d gone to film school, and decided I wanted to work for Francis Ford Coppola. Fred Roos was at Zoetrope [Coppola’s production company], and I became Fred’s personal assistant. He had this little house in Benedict Canyon, where I was living, too. The job didn’t pay much, but I did get room and board. The room I was in—well, you know that Harrison Ford was Fred’s carpenter, right? The closet in my room, which Harrison had built, had these sort of louvered wooden doors, doors that were on a track. They were hard—I mean, really hard—to open and close. I used to curse Harrison’s name every time I had to get dressed. Anyway, on the nights that Eve couldn’t stand to be at home, she’d come spend the night at Fred’s. I’d make the three of us dinner. Afterward, she’d go upstairs with Fred. She might have slept in his bed, or she might have slept on the couch in his office. That wasn’t clear to me. But I do know she was a wreck. Her dad was very ill. And my sense is that she arrived looking for comfort, not sex, and Fred was an old friend.

Sol had been in sharp decline since 1977. By January 1982, there was no lower he could go. “Dad was only seventy years old, but he looked ancient,” said Mirandi. “Huntington’s had turned him so skinny—and so crazy, my God. He refused to take antibiotics. He was convinced they were bad for him. But his teeth were giving him problems. He went to his dentist and his dentist said, ‘You’ve already had one episode with endocarditis. If you get it again, it’ll kill you. You must take antibiotics every time you have your teeth worked on.’ And so he snuck around to find a dentist who didn’t know his history, had work done without antibiotics, and, lo and behold, got endocarditis. We rushed him to Hollywood Presbyterian, where basically his heart failed and he died. But they brought him back around. He was in the hospital for weeks. Finally, they let us bring him home.”

Where Eve made sure she wasn’t. “Sol was lying there in the living room,” said Laurie. “He kept saying, ‘Where’s Evie? Where’s Evie?’ No one knew.”

This wasn’t the first time Eve had pulled a disappearing act during a family crisis. “It was like when Mother had that kidney stone and had to go to the hospital in Florence in 1962,” said Mirandi. “Eve wouldn’t visit. Not because she didn’t care. But the idea of Mother sick, of Mother possibly dying—she couldn’t handle it. That’s why Dad let her go to Rome by herself. He knew she needed to run away. And it was the same when he was dying.”

Mirandi was sympathetic to what Eve was going through, but her sympathy had its limits. “Mother was collapsed in a pile in the corner, drunk. And I was tending to Dad all by myself, managing the nurses. I tracked Eve down and I slapped her and said, ‘You have to go see Daddy.’ And thankfully she did go see him because he had just a few days left.”

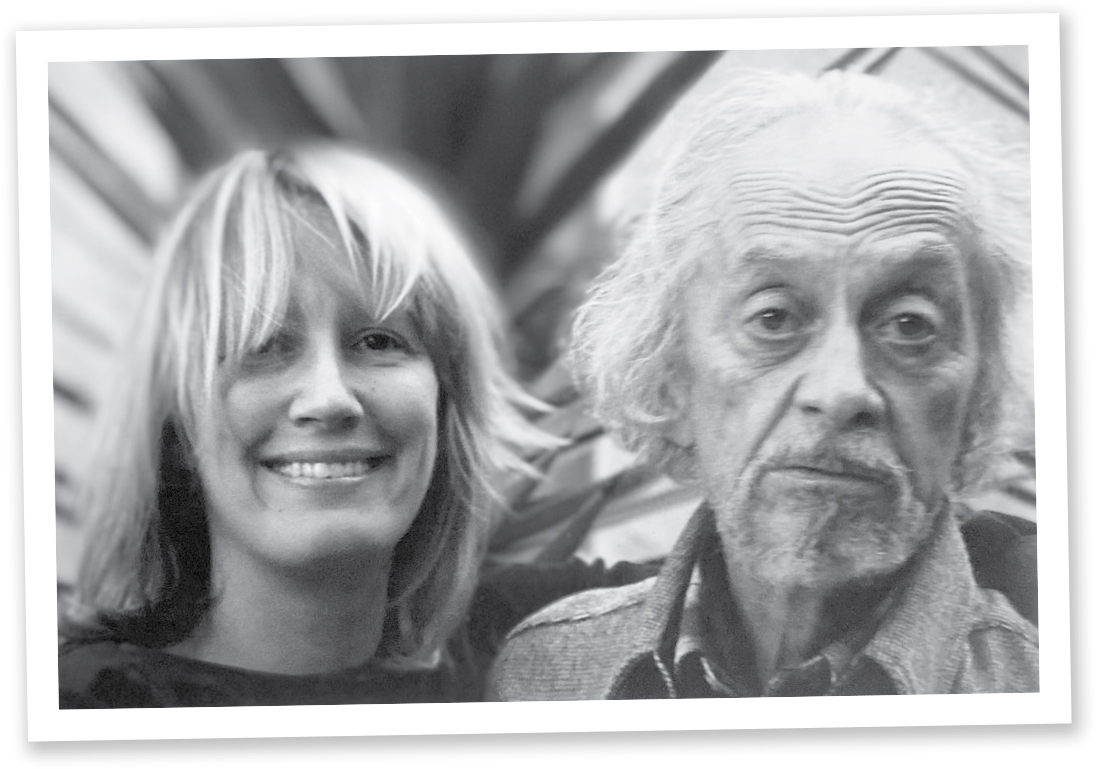

Eve and Sol.

Sol died on February 19, 1982. The cause of death was listed as endocarditis, but it was Huntington’s that killed him.

Only Sol didn’t have Huntington’s. Or so said the doctors. “Mother donated Dad’s brain to a foundation at UCLA that was doing research on Huntington’s,” said Mirandi. “It was such a rare condition that they wanted to study his brain. But then we were told by these people that his brain showed no sign of Huntington’s. Actually, I was the one who took the call from that guy, the UCLA doctor guy. He said that the Huntington’s diagnosis was a misdiagnosis—he was definitive about this—and that there was a tumor on Dad’s brain, and that was it.”

Medically, factually untrue. Eve got Huntington’s, and the only way a person can get Huntington’s is from a parent. Therefore, Sol had Huntington’s. And the doctors knew Sol had Huntington’s. So why did they suddenly start pretending otherwise? Mirandi has a theory. “Eve and I were still in our thirties in 1982. What I think was going on was that Mother didn’t want us worrying all the time that we were maybe about to get this awful, terrible disease. But Mother knows me, and she knows I’m going to dig to find out what the hell is going on. So she got somebody at UCLA—and Mother was working at UCLA at the time, in the research library—to call and pretend to be a doctor and tell me it wasn’t Huntington’s. I mean, she could sweet-talk anybody into anything. And it worked. I completely swallowed it, and so did Eve.”

No sooner was I off the phone with Mirandi than I was on the phone with Laurie. I wanted to run what Mirandi had said by her, get her reaction. “Sounds right to me,” she said. “It was absolutely in Mae’s makeup to lie about the Huntington’s. Mae was the first person to say about some unpleasant thing she couldn’t change or help, ‘Yeah, let’s forget about that. Let’s just not think about it.’ ”

It was three months after Sol died that Eve pulled herself out of the self-destructive spiral she’d been caught up in since the late seventies. “ ’Eighty-two was a big year for the family,” said Mirandi. “First Dad went, and then Art [Pepper, Laurie’s husband], and then Evie got into AA.” Before Eve could get into AA, however, L.A. Woman had to come out.

And now, a few unkind words about L.A. Woman:

With Sex and Rage, a novel, a roman à clef, a bildungsroman, Eve made a mistake. With L.A. Woman, also a novel, also a roman à clef, also a bildungsroman, Eve doubled down on that mistake. L.A. Woman even has the same weak-sauce plot as Sex and Rage, only further diluted: L.A. girl artist falls in with a fast crowd; gets her heart broken, her illusions shattered; and then reinvents herself as a (screen)writer. It’s a depleted book. A lazy book, as well. And Eve should’ve known better than to publish it.

And Eve knew she should’ve known better. “There was a review of L.A. Woman in the Times,” she said, “a horrible hideous pan by that P. J. person [P. J. O’Rourke, “Not a Bad Girl but a Dull One,” New York Times, May 2, 1982]. See, I was sure I’d written a book so wonderful I’d never have to do another thing in my life, only apparently I hadn’t. Which meant I needed to clean up my act.”

And so she did.

On May 23, 1982, Eve faced the dragon of her addiction. She got sober, and not a minute too soon. “She was having these close calls,” said Mirandi. “There was that fire she started with the heater and her fur coat. Then, just after Dad died, Michael Elias and Steve Martin got together money to put her up at the Chateau Marmont—you know, so she didn’t have to be at home. She was staying there, and she phoned a friend and said, ‘I’ve overdosed. Can you come?’ The Chateau then had this house doctor who’d give you whatever drugs you wanted. This was right around when John Belushi was doing himself in with drugs at the Chateau. So, the friend rushed over and rescued Eve. Eve was killing herself. I mean, she wasn’t trying to kill herself. She wasn’t suicidal. But she was killing herself anyway.”

Eve was killing Eve the person to give life to Eve the writer, just as she always had. And then it dawned on her that maybe Eve the writer was no longer worth the sacrifice. “Eve wasn’t able to manage it anymore—the drugs, the alcohol, the sex, the scene, all the things that she imagined fed her writing,” said Mirandi. “And when L.A. Woman came out, and it didn’t work any better than Sex and Rage had, she must’ve thought, ‘I ate up all that cocaine for this? I’m running myself into the ground for this?’ And then she got a reprieve—well, two reprieves. Mother gave her the belief that Huntington’s wasn’t a factor after all. And Dad passed. And, you have to understand, it was Dad she was playing to, Dad she’d been playing to.”

So it was Sol all along. He was the goad and the influence. It was his approval she was trying to win, his attention she was trying to hold.

“Eve was being ‘Eve,’ doing her whole spectacular thing for Sol,” said Laurie. “One day, Sol was in the house with a friend. Mirandi walked in and he said, ‘That’s my daughter, but she’s not the one.’ She’s not the one? What a devastating thing to say! I told Eve about it, and she said, ‘Yeah, well, it’s not so great when he likes you either.’ So, yes, Eve wanted to impress those other people, people like Joan and Earl. But it was Sol she wanted to impress most of all. You have no idea how important he was in our family. Sol was the judge. Sol’s word was the word. Then Sol was dead and Eve didn’t have to be spectacular anymore. She was free.”