Friday, May 4, 2012.

I arrive at the restaurant straight from the airport. Short Order, it’s called. It looks like the kind of place that sells hamburgers and hot dogs to beach bums and bunnies, only fancy. I’m an hour early, the first customer of the day, the hostess unlocking the door as I reach for it. I find a table at the back, sit there sipping a seltzer, my stomach a mess from nerves and travel and being six weeks pregnant, and wait for the woman who once said she believed that anybody who “lived past thirty just wasn’t trying hard enough to have fun,” now sixty-nine.

I don’t mind waiting for another—I glance at my cell—fifty-seven minutes. After all, I’ve already been waiting for Eve Babitz for two years.

My obsession started in 2010. I was thirty-two, living in Kips Bay with my husband Rob, then my boyfriend Rob, in a 350-square-foot apartment subsidized by NYU, where he was a medical resident. I was a writer, though I mumbled when I told people this since I wasn’t a published one. It was a weekday evening, rush hour, and I was on the subway, hanging from a pole, reading Hollywood Animal, the memoir of screenwriter Joe Eszterhas. At the top of a chapter, I came across a dynamite quote about sex and L.A. It was attributed to a person I’d never heard of before. Eve Babitz. (A curious thing. I can’t tell you the exact quote because, evidently, it doesn’t exist. Not in Hollywood Animal, anyway. I’ve searched every edition. And yet I’d swear to you that that’s how I found Eve: one Hollywood animal giving me the scent of another.)

As soon as I got home, I went on Google, discovered that Eve Babitz was a writer. Went on Amazon, discovered that her books were out of print. Fortunately, secondhand copies were available. I selected the title I liked best—Slow Days, Fast Company—clicked on the cheapest option. It was at my door the following week. I read it fast, in a single swallow, skipping meals, hardly even taking pee breaks. When I was finished, I ordered another book, then another, then another.

Eve was good. Her writing—its innocence, its sophistication, its candor, its wit, its lack of respect and willingness to fly in the face of received wisdom, its sheer headlong, impish glee—made me dizzy with pleasure. I had to talk to her. She was the secret genius of L.A., I was convinced.

But L.A.’s secret genius was also, it seemed, L.A.’s best-kept secret. There was scarcely a trace of her online: an interview she’d given to Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art in 2000 (she wasn’t even the focus of the interview, the Wasser-Duchamp photo was); a blog post by cultural critic James Wolcott; and an intriguing but brief piece by Holly Brubach for T magazine. That was it, the works. And, needless to say, she wasn’t on Facebook or MySpace or Twitter or LinkedIn.

She was, however, in the phone book. I scrawled rapturous words on the back of a postcard with Marlon Brando—a favorite of hers—on the front, dropped it in the mailbox. That didn’t work. So I hand-delivered a note to the apartment on Gardner Street. (You caught that I live in New York, right?) That didn’t work either.

When, a year or so later, I got a nibble, not even a nibble, a “Maybe, could be interesting,” from an editor who’d never heard of Eve (Bruce Handy) at a magazine I’d never written for (Vanity Fair), I sent an actual letter, claiming with wild—scratch that, with reckless—optimism that she was about to be the subject of a full-length feature and asking if she’d let me take her to lunch. Nothing.

I changed tack. For several months, I stopped concentrating on Eve, concentrated instead on those close to Eve. I reached out to her sister Mirandi, her cousin Laurie. Both were wary initially, warmed eventually. And naturally I was all over Paul Ruscha, referenced in that Archives of American Art interview.

Finally, Eve got either curious or hungry or both, and sent word through Paul that she accepted my lunch invitation. Tomorrow, she said. Noon, she said. Short Order, she said. I bought my plane ticket, flew to L.A. in the morning.

Which is why I’m sitting in a neo-fifties gourmet burger joint in the Farmers Market on Third and Fairfax, my suitcase wedged between the back of my chair and the wall. I keep checking my cell. Am staring at its screen when 11:59 changes to 12:00. My eyes begin to flick back and forth from the front door to the window overlooking the parking lot.

I’ve been telling myself a story. Namely, that Eve and I are in a story, and one so old it’s almost preordained—a romance. She hasn’t been rejecting my advances all this time. Rather, she’s been testing my devotion, making me prove how much I care. That’s the reason she’s letting me catch her now: I’ve passed, I’ve proved.

And, yes, Reader—sigh—I realize how deluded I sound, how close to lunacy. But this is Eve Babitz we’re talking about. Eve fucking Babitz. Everything she does has a wild playfulness to it, an erotic sparkle. Slow Days is a come-on. That’s the book’s structuring principle, its framing device: Eve trying to beguile a reluctant lover into turning her pages. I know, of course, that she no longer writes or sees people. This I’ve been told by everybody. Yet even her withdrawal strikes me as a seductive gesture, made by one who understands in a bone-deep way the nature of desire and how the moment it’s fulfilled is the moment it dies.

Again, I glance at my cell to check the time. I get distracted by a text message. When I look up, I spot a woman by the door. I rise from my chair, half sit back down, rise, as I think, It’s Eve, wait, it can’t be Eve, wait, it has to be Eve. Something about her is—and I don’t know how else to put this—wrong. It’s the hair that tips me off: gray and cut brutally short, almost to her scalp. And then the clothes confirm my suspicions: a dark yet faded T-shirt, stained; shapeless black pants, also stained; glasses with lenses so thick and greasy that the eyes behind them are hugely magnified, distorted.

In a flash, I understand that I’ve misread her, misread the situation, and so egregiously that I’m disoriented. I start to move in her direction, the click-clack of my high heels on the wooden floor out of sync with my walk. As I get closer, she gives me an unfocused smile. A tooth, I see, is missing, and a line from Slow Days—“I also have nearly perfect teeth, which I believe is the real secret to the universe”—begins to run through my brain like a film on a loop. I flinch but I don’t break stride.

Eve’s first words to me: “I’m starving.”

No exaggeration as it turns out. Our grass-fed burgers and russet potatoes fried in truffle oil are placed in front of us and she barely comes up for air. I remember Paul’s description of her MO at parties: “She’d bypass the host or hostess and first head to the buffet table and dive into it like Esther Williams on Dexamyl. She’d bolt if something made her uneasy, then barge back in and demand that I take her home. I’d ask her why. After all, we’d just gotten there, and she’d say, ‘So we can fuck!’ ”

The second she cleans her plate, she pushes it away. “I’m ready to go,” she says.

I blink at her. We’ve been together for twenty minutes. Not knowing what else to do, I signal for the check.

Before the waiter brings it, Eve lurches from the table. I’m afraid that she’ll walk back to her apartment, a short distance from the Farmers Market, and that I’ll never see her again. Throwing down bills, I run after her. As I follow her out the door, I ask the hostess to call a cab.

Eve talks more in it than she did in the restaurant, except I can’t track her sentences: one is about a sugar substitute used only in Japan; the one after that about the queen of England’s bra-maker; the one after that about the health benefits of unpasteurized milk. As I lean in to better hear, I become conscious of a smell coming off her. Not body odor—it isn’t tart or tangy. Something else, something I can almost identify but can’t quite. Something heavy, sweetish. I try to breathe through my mouth.

Before I know it, we’re on Gardner and Romaine, a sleepy block just south of Santa Monica Boulevard. Eve’s building is right on the corner. It’s two stories, a little run-down, a little shabby, but still pretty because of the bougainvillea and rhododendrons surrounding it, the dusty palm tree in the front yard.

The cab hasn’t rolled to a complete stop and Eve’s already getting out. She’s in a rush but not, thank goodness, fast. And, after paying the driver, wrestling my suitcase from the trunk, I catch up with her at the door. She opens it just enough to slip through. I can’t see what’s inside other than dim clutter. I can smell what’s inside, though, and it’s the same smell I smelled in the cab, only much, much stronger. It strikes me forcefully, physically, like a blow.

The door closes, the lock turns. There’s a mini staircase in front of the building. My legs crumple underneath me, and I drop to the top step. For several minutes, I just sit there, watch the sun dancing in the polished metal of the hubcaps of the parked cars, listen to the breeze rattling through the leaves of the palm, and wait for my head to clear, my stomach to settle. I keep expecting to feel some particular way about the encounter—upset or sad or depressed or frightened. Instead, I feel a jumble of all these things.

What I also feel and what I mostly feel, though, is excitement. Eve and I are in a story together, just like I’d thought. Where I was mistaken is in the kind of story. It isn’t a romance. Is something far more primal, far more urgent.

A Greek myth.

Of course Eve can’t be found in the phone book or West Hollywood or any other location easily got to. No, she’s in the underworld, Hades, a place of darkness and dankness, chill and rot. And there she’s being held captive by a ferocious dog with three heads, the heads: isolation, decay, despair. (That’s what she reeks of, what her apartment reeks of. That’s the smell I couldn’t put my finger on.) My task is to rescue her from that monster, return her to life aboveground.

And, yes, Reader, I realize I now sound even more deluded, even closer to lunacy, but I don’t care. What I’m saying is real and deep and true.

It took two years for the Vanity Fair piece to come out. During those two years, I insinuated myself into Eve’s life, flying to L.A. every six to eight weeks to see her, take her to breakfast and lunch. (Normally I’d do two meals a day since no meal lasted longer than half an hour, and never dinner because she disliked going out at night.)

Among the vital things I learned: how to speak Eve. She often communicated in code, and that code was not easy to crack. “Is that the blue you’re using?” was, obviously, one example. Another was “little rascals.” (“Little rascals” were pills, usually Valium, though not always.) Another was “so-and-so likes baseball.” That meant the so-and-so in question, male, was heterosexual and serious about it, macho in attitude and outlook. As in, “Oh, Fred Roos liked baseball too much to be friends with Earl.” And then there was “cramp my style,” a phrase I’d heard her invoke in response to the Brownies, but also higher education, deadlines, religion, cookbooks, blue jeans—anything, basically, that threatened her ability to do exactly as she pleased.

Equally vital: how much pain she was in at all times. A number of her burns had never fully healed, remained raw, open. And her body couldn’t efficiently rid itself of heat since the fire destroyed most of her sweat glands. Sitting for an extended period, especially in warm weather, was excruciating for her. (Eve didn’t tell me this because Eve wouldn’t. It was Mirandi who told me.)

And perhaps most vital of all: how little contact she had with the outside world. She’d quit driving years ago. Her only excursions were her twice-weekly strolls to the Farmers Market, her Sunday AA meetings, her Saturday lunches with Mirandi and Alan, Laurie or Dickie Davis occasionally joining. Her phone still rang, though not as frequently as it used to. The fire—or, rather, the effort to drum up money for the hospital bills resulting from the fire—had exhausted many of her friends. Their goodwill was tapped out. Besides, they were, in the main, artists and writers, and artists and writers tend to be politically liberal—as she herself was up until 2001—and were therefore less than keen to discuss with her the sexiness of Israeli ambassador Danny Danon’s sneer, or share in her delight at the botched rollout of Obama’s healthcare website.

Eve never owned a computer. And she’d gotten rid of her TV at Mirandi’s insistence. (“She was going broke from the Home Shopping Network,” said Mirandi. “They showed it, she bought it.”) All she had was a portable radio with a massive antenna always tuned in to KEIB or KRLA, Los Angeles’s conservative talk stations. “Eve started getting into conservatism sometime after 9/11 with Dennis Prager.” Mirandi raised her hands, palms turned up, empty. “I don’t know,” she said. “Dennis is Jewish, from Brooklyn, with a voice exactly like Dad’s. Then it was funny guys like Dennis Miller and Larry Elder. I think part of it was that she liked the male company.”

Eve had gone from Democrat to Republican. She also, though, had gone from sane to crazy, and one of the forms the craziness took was her Republicanism. (I am not—I repeat, I am not—saying that “Republicanism” and “craziness” are synonymous. They just happen to be in Eve’s case.) For instance, late in the Trump presidency, she began to believe that she and Trump were having an affair, and that she was meeting him for trysts at the very bungalow in the Beverly Hills Hotel where she met Ahmet Ertegun for trysts half a century earlier.

I loved having Eve all to myself. She wasn’t just L.A.’s secret genius who was also L.A.’s best-kept secret, she was my secret genius who was also my best-kept secret. And then I went and blabbed in the March 2014 issue—the Hollywood issue, fittingly enough—of Vanity Fair, and the secret was out.

Now, the secret would’ve come out whether I blabbed or not. Eve’s genius was too clear, too shining, too true, to stay under wraps forever. And nowhere was that genius more in evidence than in her books, all seven of which were reissued after the Vanity Fair piece appeared. New York Review Books Classics in particular did right by her. They’d bring back her two oldest and best: Eve’s Hollywood in 2015; Slow Days, Fast Company in 2016. And, in 2019, they’d bring out a brand-new collection: I Used to Be Charming, the title story a masterful editing job, Sara Kramer somehow turning the forty pages of false starts and disjointed fragments into a coherent and engrossing narrative with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

So, my piece didn’t change things so much as goose them. Had it not been written, Eve’s late-blooming chic would’ve bloomed a little later is all. From Slow Days:

During a shaky week-long period of my life[,] I was confronted with the possibility that a book I’d written might become a best-seller… I did not become famous but I got near enough to smell the stench of success. It smelt like burnt cloth and rancid gardenias.

Slow Days, though, was published in 1977, when she was in her mid-thirties, and she’s describing something that happened—almost happened—when Eve’s Hollywood was published in 1974, and she was in her early thirties. The question becomes: was the smell any sweeter now that she was in her seventies and not just near fame but at it, in it, of it?

Since I started writing this book, I’ve spent a lot of time holding up my memory of that first meeting between me and Eve, looking at it from another perspective.

Hers.

Eve, I think, also believed we were in a Greek myth. Only, as she saw it, Hades wasn’t a place she’d been forcibly consigned to but willingly retreated. The three-headed dog wasn’t her vicious captor but her staunch protector. Isolation, decay, and despair weren’t sources of torment and terror but solace and comfort. And I—well, I wasn’t a heroic figure, a savior, at all. I was the villain. I was the monster. A figure of dread and menace intent on thrusting her back into the sunlight, exposing her to its pitiless glare, restoring her to a world that had treated her with cruel indifference, and from which she’d barely escaped with her life.

“Of course Evie was scared of you,” said Laurie. “You represented that whole East Coast literary world. She thought East Coast people were snotty, and that they had no right to be snotty. But she also had a lurking fear that maybe they did have the right, and that maybe they knew better. To get reviewed in the New York Times back then was really just it. And, oh God, the Times was horrible to her—horrible! Over and over again. That last review nearly killed her.”

That last review: Michiko Kakutani on Black Swans. Kakutani closed her assessment—negative, naturally—with the suggestion that Eve (deep breath) “maybe take a vacation from L.A.”

Maybe take a vacation from L.A.

But Kakutani’s review was in keeping with the reviews Eve had received throughout her career. The Establishment critics always saw her as a ding-a-ling from Lala Land; an airhead attempting to pass for an egghead; Eve Bah-bitz, with the great big tits.

Any time Eve wrote about Marilyn Monroe, she was really writing about herself. Eve on Marilyn’s overdose:

Marilyn kept putting herself in people’s hands, believed them. They let her think she was just a shitty Hollywood actress and Arthur Miller was a brilliant genius… No wonder she liked to sleep.

And here I was, trying to shake Eve awake.

The Vanity Fair piece got the ball rolling, and soon its momentum was unstoppable. It was the reprints of Eve’s books, and the ecstasy those reprints inspired, that did much of it, of course. Yet Eve was touching imaginations in ways that couldn’t be explained by the brilliance of her books alone. It was something about her, about Eve qua Eve, and what she stood for—free and original thinking, joy, hauteur, endurance, sex-and-drug-saturated bad behavior redeemed through obsessive hard work—and how it contrasted with the moment we were in—po-faced, whey-faced, mealy-mouthed—a historical period defined by its earnestness and hypocrisy, by its love of hall monitors.

And young women already in style and unassailably cool were confirming and enhancing their vogue by associating with her. To wit: in 2017, New Yorker It girl Jia Tolentino, and Girls It girl Zosia Mamet, appeared alongside Stephanie Danler, writer of Sweetbitter, the It novel of the year before, on a panel dedicated to Eve at the New York Public Library. That same year, actress-ingénue Emma Roberts posted on Instagram a picture of herself lying on a chaise longue, lost in a mood, Sex and Rage open on her chest, the blood-red polish on her nails matching the blood-red lettering on the book’s cover. In 2019, model-mogul Kendall Jenner was photographed on a yacht off the coast of Miami Beach in the briefest of bikinis, the reissue of Black Swans peeking coyly out of her tote.

I suspect, too, that once Eve’s second letter to Heller starts to circulate, get known, the nature of young women’s interest in her will shift. In the last few years, that interest has lain in her radiant intelligence, her nose-thumbing recklessness, her gift for life. In future years, though, I bet it rests largely on the courage of her efforts, the anguish of her defeats. She’ll become a totemic figure, particularly to young women in the arts, the ones who understand from experience what she went through. And when they speak of her, it’ll be in hushed tones. Just you watch.

Between 2014 and 2021, Eve went from nowhere to everywhere. It was like she’d skipped fame and fortune—bourgeois aspirations—and gone straight to legend.

To the general public, this was a happily-ever-after ending. A jewel had been fished out of the trash heap of history, and in the nick of time. She was still around to enjoy her glory. But the truth was, she wasn’t still around. Since 2001, the year Huntington’s began to take her over, she’d existed in a kind of posthumous state. As if she’d somehow contrived to outlive herself.

Which is perhaps why the ending was, for Eve, unhappily ever after. “It’s too late,” she’d mutter darkly to Mirandi as the media requests began to trickle in, then pour in. Mirandi shielded Eve from the sudden celebrity, responding to all reporters’ queries over email in the guise of Eve. Mirandi also shielded the sudden celebrity from Eve, who simply couldn’t be trusted not to blow it up in some spectacular fashion. (Eve almost blew it up spectacularly anyway. In 2017, she got a friend from AA to log her onto Facebook, where she went on quite a spree. “Democrats started the KKK!” she wrote. And, “I love Rush Limbaugh!” Mirandi took down the posts as soon as she was alerted, put up a post stating that Eve’s account had been hacked. She then tore into Eve, who was properly chastened, and the AA bud, who was properly terrified. And that was it for the online shenanigans.)

Really, though, and in fact, the ending for Eve was ambiguously ever after. Her new popularity and acclaim only sometimes freaked her out. Other times she thought what was happening to her was pretty okay, and maybe even funny. (“It used to be only men who liked me,” she said. “Now it’s only girls.”) In short, those gardenias blew rancid or intoxicating depending on her mood, the weather, how delicious or not delicious her breakfast had been, the number of Zs she’d copped the night before.

One of the last scenes Eve and I played together:

January 2018. Musso’s, the old show-business-crowd steakhouse on Hollywood Boulevard. It had recently been announced in the trades that Hulu was developing a comedy series based on Eve’s books, and I was taking her to lunch to celebrate. Mirandi and Laurie were also there. Only, in the case of Laurie, not yet. (Traffic.) And, in the case of Mirandi, yet but not at that second. (Bathroom.) Eve and I were alone.

I was about to ask her if she was going to order the sand dabs—a dumb question, she always ordered the sand dabs—when she turned to me and said, “I guess I ought to thank you.”

I didn’t respond because I didn’t know how to. Was she thanking me? Not quite. And I wouldn’t have been able to bear it if she was. (A moist-eyed Eve, humble and full of gratitude, wasn’t Eve as far as I was concerned.) The smile on her face flickered on and off—a neon sign with faulty wiring—and she was looking at me intently, something I don’t believe she’d ever done before. I felt the need to speak, only I couldn’t think what to say.

A frozen moment.

And then the moment passed. Laurie, collapsing theatrically in the seat beside me, wrist flung to forehead, said, “The drive here was craaaaazy.”

And, before I knew it, Mirandi was at the table, too, and an energetic discussion ensued about whether it was best to take Los Feliz or Franklin when coming to Hollywood from the Eastside at midday.

Yet, for me, the moment never passed. Maybe because it was such a charged one, and for reasons I didn’t grasp at the time. I do now. It was the sole instance of Eve acknowledging, even if only obliquely, the complexity—and the complicity—of our relationship.

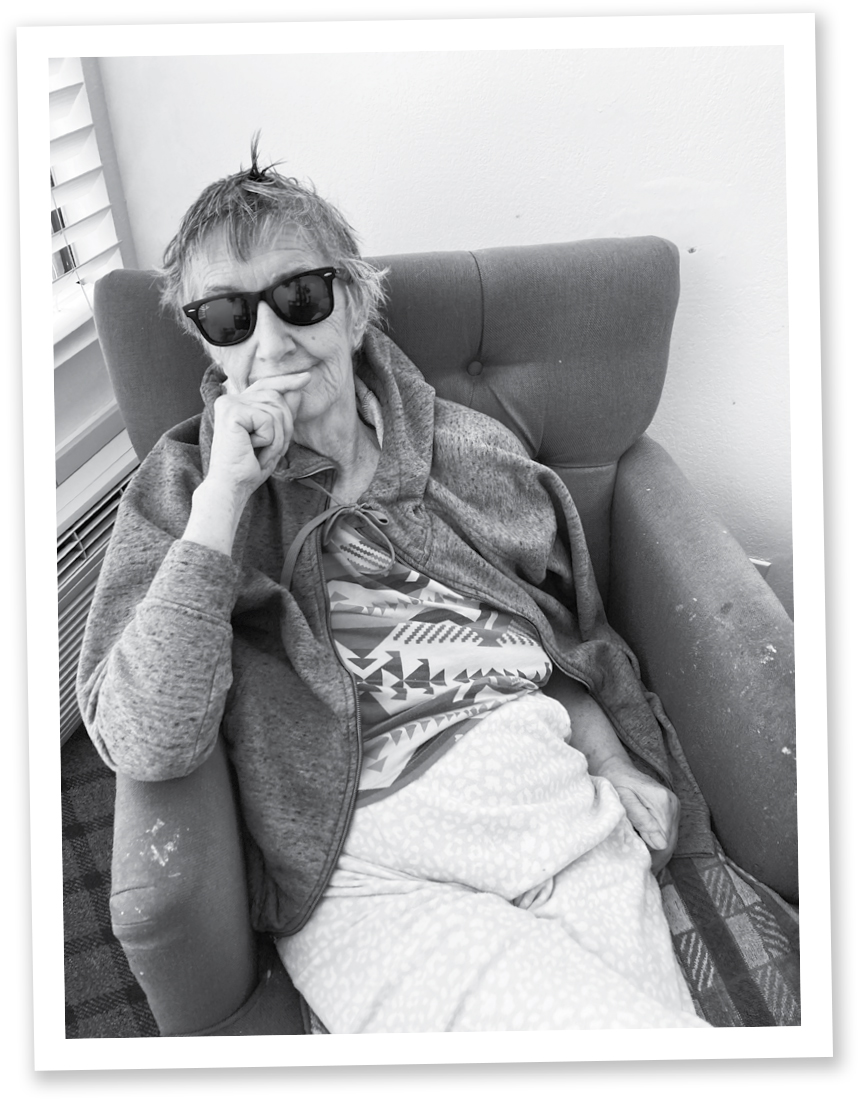

Eve, near the end, in a pair of sunglasses I sent her.

This relationship was nonexistent when we were actually together. Our in-person encounters were always edgy, jarring, frustrating. I loved her, as it so happened. As it also so happened, she was an absolute terror, and anyone who approached her about her work in a manner she didn’t like got a brutal, if hilarious, reception. (A memory of Paul’s: “A guy came up to her at a party and told her that she was his favorite writer, and she just looked at him and said, ‘Beat it.’ ”) The prospect of annoying her or pissing her off or losing her respect filled me with dread. How could I ever even consider relaxing around her?

Second of all, there was the game of Beat the Clock that we were never not playing. I knew how quickly she was going to want to leave wherever it was we were. Which is why I overdirected our conversations, tried to rein her in if she wandered off on one of her tangents. (“Where can I find a blouse the same shade of blue as Melania Trump’s eyes?”) And I’m sure my wound-up intensity was unnerving for her, that habit I couldn’t seem to break of looking at her too hard, of lunging at every remark as soon as it dropped from her lips.

This relationship did exist, however, when we were apart. It was conducted entirely over the phone, and was entirely private—just the two of us on the line.

It began on May 5, 2012, the day after the disastrous Short Order outing. I remember the grudgingness with which I reached for my cell that morning. Our lunch couldn’t have gone worse. I’d blown it with her, totally and completely. The situation was hopeless. Yet I knew that I had to do the responsible thing, the adult thing, the right thing, and finish what I’d started, thank her for meeting me. Oh, but I didn’t want to! (Forcing myself on her again?) In any case, I was certain she wouldn’t pick up.

But, to my astonishment, she did. To my greater astonishment, she sounded pleased that it was me on the other end of the phone. Our exchange was brief. She brought it to a close by saying, “And next time, I want you to take me for barbecue.” Next time. The relief I felt at hearing those two words was so intense it made my vision blur. As I said a good-bye she didn’t catch (she’d already hung up), my heart lifted, lifted, lifted.

I was in.

From then on, Eve took my calls, and I made them, twice a week, minimum, for years. “Oui, oui?” she’d say, by way of greeting. I’d tell her who it was. “Lili!” she’d say, the exclamation point audible in her voice, which—and I thought this every time I heard it, the same thought, without fail—was so charming, unusually charming. It was girlish and lilting, its enunciation softly crisp, laughter bubbling up in it like fizz in a bottle of champagne. Yet it was drowsy, too, as if the phone’s ringing had wrested her from a post-sex-romp slumber. And this was what I began to picture: Eve, but not Eve now; Eve then, Eve’s Hollywood–era Eve, sitting up in bed, tousle-haired and mascara-smeared, a sheet wrapped around her torso, the receiver cradled between her jaw and shoulder, a man beside her, only his back visible, trying to hold on to sleep.

What we mostly talked about was the past. The things she said were invariably sharp and amusing. On the style of Edie Sedgwick: “She used to buy her clothes in the boys’ section.” On the sexual capacity of Harrison Ford: “The thing about Harrison was Harrison could fuck, nine people a day.” On the non-presence of Warren Beatty: “I met him about eight million times but I never recognized him. He’s one of those people who doesn’t show up for me.”

She was great on the present, as well, if you were willing to wait out the political rants. On reading Life, Keith Richards’s autobiography: “The reason Keith doesn’t die is because he doesn’t mix his drugs.” On Justin Bieber’s third album: “So good, and he could get by on sheer cuteness if he wanted to.” On her skin after the fire: “I’m a mermaid now, half my body.”

It was the last line that knocked me out the most. I loved it not only because it showed how tough she was, how unbowed, what a sport and a champ and a trouper, but because of its sneaky eroticism. She was comparing her burned epidermis, a painful and grisly condition, to the scales on the tail of a mermaid, the femme fatale of the sea. The image is horrifying and titillating at once. As grotesque as it is sexy.

On the phone, she talked like she looked in that photo (Leibovitz’s for Eve’s Hollywood). On the phone, she talked like she wrote in that book (Slow Days, Fast Company). On the phone, she was what Laurie said she couldn’t be anymore: she was Eve Babitz.

Eve’s first successful artistic act was, of course, posing for Julian Wasser—naked, hair covering her face like a veil, trying to checkmate Marcel Duchamp. When the boxes were found, and I saw what was inside them, began to consider retelling her story, it was to the Wasser-Duchamp photograph that my mind kept returning. That photo told a psychological truth about her, I was sure. Expressed succinctly and eloquently her contradictory attitude toward fame: she wanted to be the person all eyes turned to while simultaneously staying out of sight; to be the center of attention yet offstage; to be a star who was also an unknown.

I was wrong earlier when I said that the secret of Eve would’ve come out whether I blabbed or not. Or, rather, I was right and wrong. Right since Eve is a literary heroine because of what she wrote, and some well-positioned somebody, at some point, would’ve stumbled across her books, twigged to how good the best of them are, started shouting, and she’d have assumed her proper place in the pantheon. Wrong since Eve is a cultural heroine because of who she was, something only she could explain to us. And, in 2012, she was already so close to gaga.

I was wrong, too, when I said that Huntington’s + Mae going into assisted living was Eve’s last turning point. It was, in fact, Eve’s second-to-last turning point. The last was, as you’ve probably guessed, Reader, the Vanity Fair piece. It set things in motion for Eve by laying out, in an orderly fashion, her disorderly life. Let people take in the scope of it, the scale, its grandeur and folly, glamour and grime, beauty and horror. And Eve was the one doing the laying, giving me—giving us—the lowdown on all of it.

At seventy, she was finally ready to push back the veil of her hair and show her face to the world.

Eve’s move from culturally marginal to culturally central was so rapid that my brain never quite caught up, was always lagging slightly behind. I can still remember the shock when, in the summer of 2021, I spotted, on the plywood wall of a construction site on the corner of Canal and Hudson, a poster. It depicted a beautiful female face, the mouth gargantuan and wide open, a miniature copy of Sex and Rage being dropped in. Beside the image were the words “Feed your mind.” This poster, so blatant, so mysterious, seemed to be speaking directly to me, and I wondered for a second if it was a message from Eve, marooned in the old-age home in Westwood, no phone in her room—a cross-country, telepathic prod: Call me. (It wasn’t. It was an ad for Folio Bookshop.)

Can remember, too, the shock when, the year before, in the summer of 2020, I heard writer-editor Gerry Howard, as he introduced me at a reading for Hollywood’s Eve in Tuxedo Park, describe Eve as “one of late-twentieth-century L.A.’s greatest living chroniclers, starting to eclipse even the mighty Joan Didion.” It was his casual tone, like what he was saying wasn’t especially daring or controversial, that floored me most.

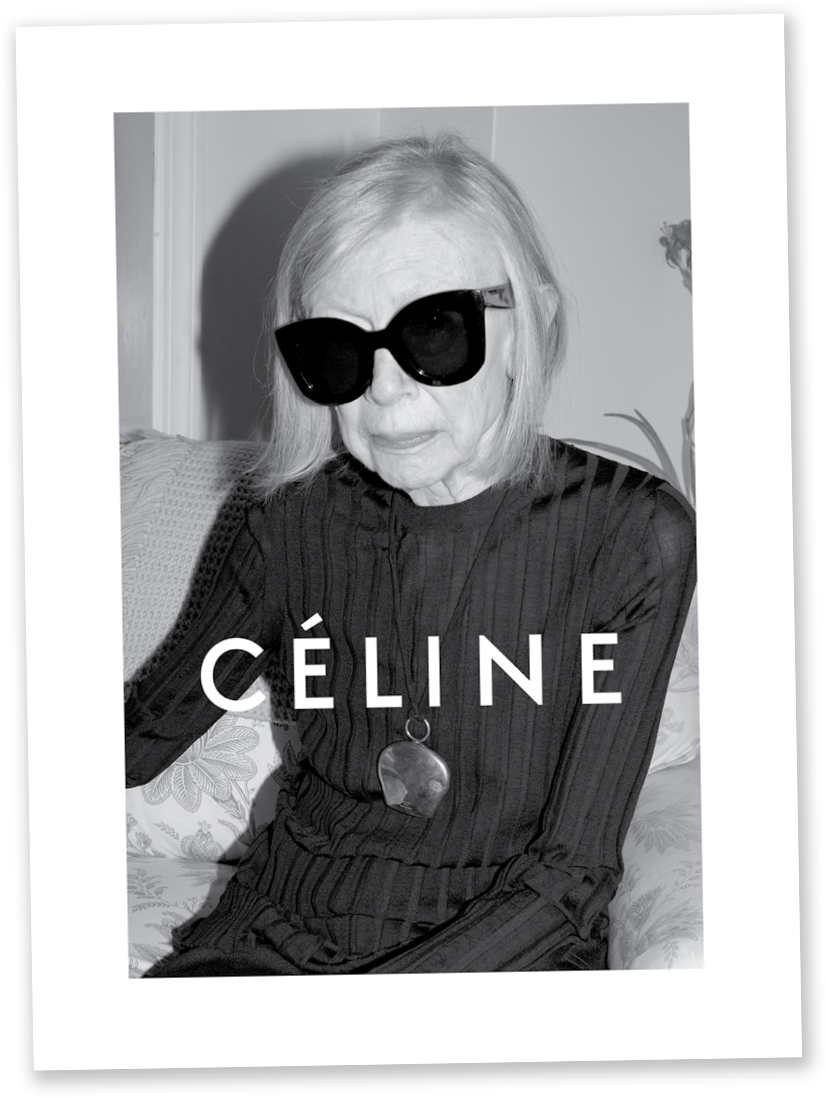

His words proved that the competition between Joan and Eve wasn’t over as it appeared to be in 1979, when Joan came out with The White Album; Eve with Sex and Rage. Or in 2000, when Joan was invited on In Depth for a career retrospective; Eve called in to In Depth for no reason at all really, just to say hi. Or even in 2005 and 2011, when Joan published The Year of Magical Thinking and Blue Nights respectively (the grief memoirs were, I think, her sensing the world’s eagerness to sentimentalize her, accommodating that wish), and in 2015, when Joan modeled for the French luxury brand Céline (the high-fashion foray was, I think, her sensing the world’s eagerness to glamorize her, accommodating that wish); and Eve barely left the one-bedroom apartment that smelled like pee-you, that smelled like shit, that smelled like insanity.

Joan, a Céline cover girl at eighty.

(Joan Didion, Céline Campaign SS 2015, New York 2014 © Juergen Teller)

No, the competition was ongoing, the stakes of the competition not just raised but changed. For years it seemed as though Eve had been left behind by Joan. Now it seemed as though Eve had, perhaps, been waiting in front for Joan the whole time.

And, anyway, what if the competition wasn’t a competition at all? What if the competition was actually a cooperation, Joan and Eve writing L.A. together? Yes, their sensibilities were polarized, their styles clashing. Their intentions, though, were identical: to make literature that exploited what was novel and exposed what was familiar in a city, a society, and an epoch under convulsive pressure.

Slow Days, Fast Company is, in my opinion, as necessary to The White Album as The White Album is necessary to Slow Days, Fast Company. To read just one of the books is to get just half of the story. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that The White Album without Slow Days is the sun without the moon, but close. Or maybe I would go so far. Maybe I’d also go so far as to say that Joan Didion without Eve Babitz is the sun without the moon.

Joan and Eve are the two halves of American womanhood, representing forces that are, on the surface, in conflict yet secretly aligned—the superego and the id, Thanatos and Eros, yang and yin. (That’s why it was so stupid of me to pick a side, declare myself proudly “for” Eve, as though both sides weren’t equally essential, equally valid, equally compelling. That’s why it was even stupider of me to pretend that a side stayed picked, as though I didn’t sometimes stray from Eve’s side to Joan’s when no one was looking.)

Eve, by the way, did go so far as to say it. Said it in her dedication in Eve’s Hollywood: “And to the Didion-Dunnes for having to be who I’m not,” a definition of Joan that is a definition of herself as the un-Joan; a definition that gets to the heart of their circularity and interchangeability; a definition that tells you nothing while telling you all there is to tell. Joan didn’t go so far as to say it, but that doesn’t mean she didn’t go so far as to think it. And though she never dedicated a book to Eve, if she had, that dedication surely would’ve said, “And to Eve Babitz for having to be who I’m not.”

Even the universe said it.

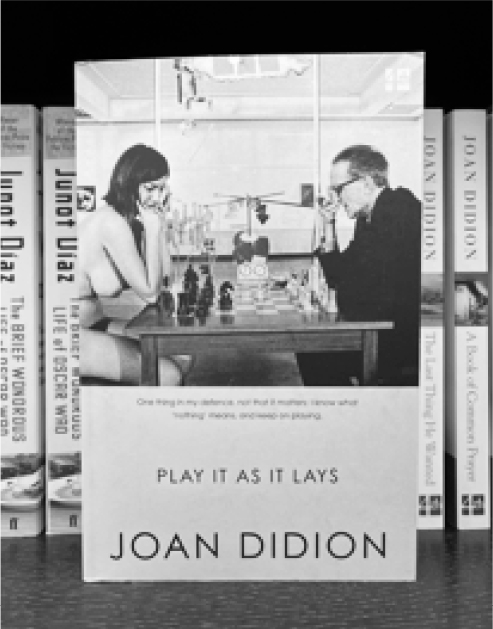

Said it in ways trivial. The cover of the 2011 British edition of Play It as It Lays features—perversely, poetically—not Joan but Eve, an outtake from the Wasser-Duchamp session. (A perfect example of what Andy Warhol called, “[getting] it exactly wrong.”)

Said it in ways profound. On December 17, 2021, Eve died of complications from Huntington’s. Six days later, on December 23, 2021, Joan died of complications from Parkinson’s.

The Brits get it right by getting it wrong.

How each handled death is almost as revealing as how each handled life:

Since I’d known Eve, she’d been slowly declining. Then, in that last week, a sudden rush to oblivion.

Her memorial was held as soon as the holidays would permit, shortly after the first of the year, at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, the final resting place of the Sheik, Rudolph Valentino, and outdoors as the Omicron variant of Covid was surging. Attendance wasn’t what it might have been because of the virus, and because it all came together so last-minute, the invitations issued by phone and haphazardly, no list prepared, just whoever happened to jump to mind in the moment. The people who showed up, though, were a game lot. And the Los Angeles Times sent a reporter, which made the occasion the exact right amount of official. And it was a good time, weird as that sounds—buoyant. Maybe because Eve’s death wasn’t premature, was overdue, and therefore a relief. (She was in such bad shape by the end.) Plus, most of those who spoke were professional performers or AA veterans or both, and the stories they told were dirty, nasty, rude, and fun to listen to.

The standout for me was Ronee Blakley, who didn’t tell a story, who read a poem, an original composition titled “Eve”:

Oh, Eve, you were hot, you were cool.

You had the biggest breasts in school.

You wrote by early day and partied all night.

How did you ever sleep enough to feel alright?

[… ]

A prose poet in everyday talk,

You gave it your all as you walked the walk.

You lived like a man, independent and free,

Becoming whoever you wanted to be,

Unimprisoned by femininity.

[… ]

You documented us in the acts of our age,

In Eve’s Hollywood and Sex and Rage.

None of that phony expected stuff,

Only cold hard news disguised as fluff.

[… ]

You were fun and smart,

Lovers had to take heart,

For which among them could equal your art?

Joan’s memorial was held at the Episcopal Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, and nine months after her death, on the first day of fall, September 21, 2022, the decision made to stare Covid down, wait Covid out, give Covid not a single inch, as she doubtless would have wanted. Her publisher, Knopf, threw it. (Threw, past tense of throw, is a party verb and thus an odd verb to use in the context of a memorial, only it’s the proper verb to use in the context of this memorial since a party, smooth and elegant if a little dour, is precisely what this memorial was.)

It was covered widely, though most deeply by the New York Times. And the title of the Times’ article, “A Star-Studded Goodbye to All That,” best captures its spirit. Packing the pews, celebrity writers: Carl Bernstein (fun fact: Jacob Bernstein, Carl Bernstein’s son with another celebrity writer, Nora Ephron, wrote the Times article), Fran Lebowitz, Donna Tartt. Celebrity photographers: Brigitte Lacombe, Annie Leibovitz. Celebrity celebrities: Anjelica Huston, Greta Gerwig, Charlie Rose, Liam Neeson, the widower of Natasha Richardson, who’d married her first husband at Joan and Dunne’s apartment back in 1990. Speakers included: Natasha Richardson’s mother, Vanessa Redgrave, who’d played Joan in David Hare’s production of The Year of Magical Thinking; New Yorker editor David Remnick; writers Susanna Moore, Calvin Trillin, Hilton Als, Jia Tolentino; the longest-serving governor in California history, Jerry Brown; and former Supreme Court justice Anthony Kennedy. Patti Smith, who’d also performed at Quintana’s funeral, closed by singing a Bob Dylan ballad, “Chimes of Freedom.”

As I scanned the names of the attendees and participants, I thought of a story Griffin had told me. He was a teenager, wandering through one of Joan and Dunne’s parties. He ran into Earl McGrath. Happy to see a familiar face, eager to see another, he asked Earl if Earl knew where Dunne was. “And Earl said to me, ‘Look for the most famous person in the room, and there you’ll find your uncle, following the famous person around like a drooling puppy.’ ” Were Dunne still alive and at Joan’s memorial, he’d have split himself in two, then in four, then in pieces trying to follow multiple famous people at the same time, drool leaking from every pore.

Death, as it happened, suited Joan. She was so good at it. Her memorial was the hottest ticket in town, proof that nobody can keep it up forever, except her. (If Slouching Towards Bethlehem and Play It as It Lays made her a literary celebrity, if The White Album made her a cultural institution, if The Year of Magical Thinking made her a secular holy woman, then the memorial made her a fame supernova: she was now someone who turned stars into fans.) To have been invited was a sign of status. Merely to acknowledge her passing was a sign of status. There were posts on social media from actress-producer Reese Witherspoon—“Thank you #JoanDidion”—and singer-songwriter Phoebe Bridgers—“RIP Joan,” followed by an extended quote from “Goodbye to All That”—and California governor Gavin Newsom—“California belonged to Joan Didion; we cherish her memory”—and Smiths guitarist Johnny Marr—“a singular genius and inspiration”—and Wonder Woman Lynda Carter—“We will miss you, Joan Didion”—and pop sensation Harry Styles—a photo of Joan with an emoji heart at the bottom. It’s impossible to imagine the demise of any other writer commanding such a prolonged and public outpouring of emotion. You might almost be fooled into thinking that the world cared about books or the people who made them.

On the day Joan’s obituary appeared in the New York Times, journalist and podcaster Maris Kreizman took to Twitter. “I want to believe that Joan Didion lived an extra week out of spite so that she could officially outlive Eve Babitz,” she wrote in a tweet that went viral. Reading it, I laughed. It was a funny line, but not, in my view, an accurate assessment. Joan wasn’t trying to one-up Eve. Joan was, if anything, trying to join Eve.

As I see it, Eve, with her string of storied lovers, and Joan, with her storied marriage, were both alone. I don’t mean alone at the end. I mean alone always, alone fundamentally. At their cores, these women were solitary, private, implacable, independent in thought and action, near ascetic in habit, almost fanatical in toughness, with spirits indomitable and inviolable. Virgins—or spinsters—in the deepest sense. Brides of Art. No man truly touched either. And each was the closest the other had to a secret twin or sharer.

To a soul mate.