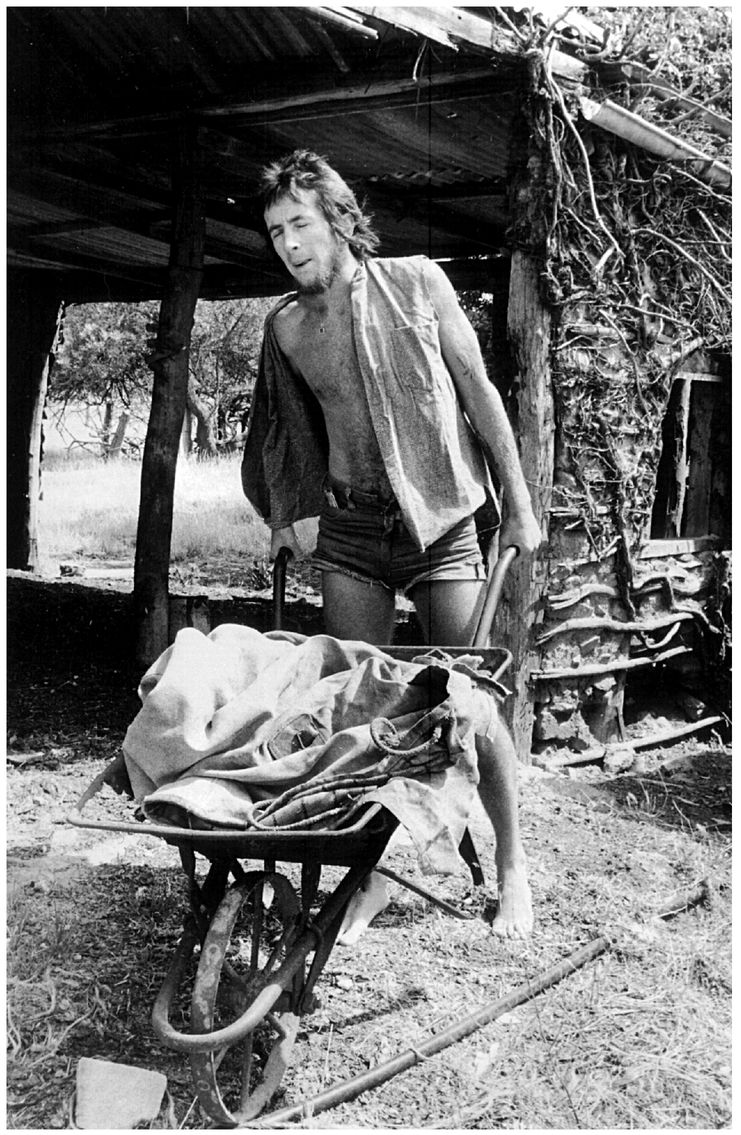

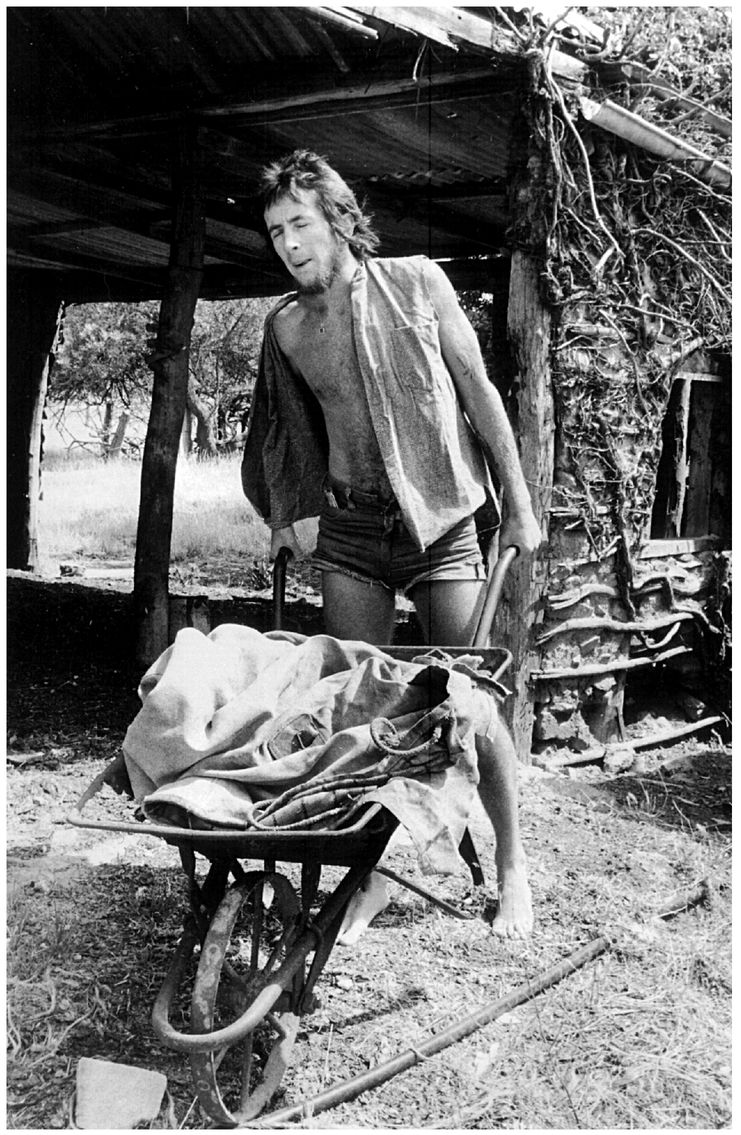

Up in the hills: Bon helps prepare the site for the Myponga Pop Festival outside Adelaide, January 1971. (courtesy John Freeman)

1. ADELAIDE, 1974

Well, I feel like a shirt that ain’t been worn

Feel like a sheep that ain’t been shorn

Feel like a baby that ain’t been born

Feel like a rip that ain’t been torn

Wish I’d done something so I could boast

But I’ve had one less than the Holy Ghost

And I hear that he’s had less than most

I been up in the hills too long

That old sow’s gettin’ too old now

I been up in the hills too long

Ain’t a thing on the farm that’s safe from harm

I been up in the hills too long

Well, I feel like a song that ain’t been sung

I feel like a phone that ain’t been rung

I feel like a barrel that ain’t been brung

Feel like a murderer that ain’t been hung

Wish I’d done something so I could brag

I feel like a squirrel that ain’t been bagged

25 years and I ain’t been shagged

Been up in the hills too long

Well, I feel like an egg that ain’t been laid

I feel like a bill that ain’t been paid

I feel like a giant that ain’t been slayed

I feel like a sayin’ that ain’t been sayed

Well, I don’t think things can get much worse

I feel my life is in reverse

One more fuck it’ll be my first

I been up in the hills too long.

—Bon Scott, “Been Up in the Hills Too Long” (1974)

FEBRUARY 1974. Bon Scott was working on the weigh bridge at the Wallaroo fertilizer plant, down by the docks at Port Adelaide, South Australia. Loading trucks. Unloading trucks. It was backbreaking work, but Bon had never been afraid of work. He was a Scot, after all, and the Scots virtually invented the Protestant work ethic.

He sweated it out in the heat and grime, listening to a transistor radio. Bon was a small man—5’ 5”—but somehow he was imposing. He had an implacable sort of frame. It took punishment well. The tattoos completed the picture.

No, Bon wasn’t afraid of hard work—Bon Scott wasn’t afraid of anything—it was just that he preferred not to have to do it. That, after all, was why he had got into rock’n’roll in the first place. It wasn’t even so much for the chicks, because Bon could always score—women just seemed to like Bon, and Bon loved women. It was work Bon wanted to avoid, the daily, nine-to-five grind of selling that too-large a piece of your soul in return for what? A nagging wife, an interminable mortgage, screaming hungry mouths to feed? The last thing Bon ever wanted was to feel a yoke around his neck.

Bon wanted to be able to wake up when he felt like it, wherever he found himself. He wanted to do as he pleased, see the world, try everything. He wanted to be able to get on stage and strut his stuff and feel people appreciated it. He wanted to be able to believe in himself.

But Bon’s rock’n’roll dream had recently gone wrong. He’d just returned from England with, or rather without, Fraternity, the band he’d joined after the Valentines broke up. A wastrel tribe of spoiled hippies, Fraternity had gone overseas expecting success to land in their lap. When that didn’t happen, they were stumped. Eventually they straggled home, embittered and in disarray.

With his young marriage also in tatters, Bon was altogether without a rudder. It was the first time since before he joined his first band, the Spektors, in 1964 that he was not in a band; and being in a rock’n’roll band that was going somewhere, or at least entertained the hope of going somewhere, was what justified Bon’s life. Not since the Spektors turned pro had Bon worked a day job. He didn’t even have his wife Irene to support him now.

Bon was crashing at a tiny place former Fraternity leader Bruce Howe had in Semaphore. He was getting around on the new bike he’d bought—a Triumph, which everyone told him was just too big—and seeing Irene and squabbling with her.

To keep himself out of any more trouble, and just to keep his hand in, Bon was mucking around with an outfit called the Mount Lofty Rangers, and it was then that he wrote “Been Up in the Hills Too Long.” A bluegrass stomp, it referred nominally to the farm in the Adelaide hills that had once been Fraternity’s communal home. But with its mood of discontent, it was perhaps more prophetic than literal.

One Friday night in late February, the Rangers were rehearsing at the Old Lion Hotel in North Adelaide. Bon arrived on his bike, late, and a bit pissed. There was nothing unusual in that. Bon was always running late, and he always carried a flask of Johnnie Walker or Southern Comfort in his pocket. The heady days of tripping were over, but the scene had now become a pretty heavy drinking one.

Bon was upset and angry. He’d had a tiff with Irene. That wasn’t unusual either—Bon and Irene fought all the time—but this time Bon had been tipped over the edge. Bon’s fuse was by any standards a long one; but that night, with all the energy that had previously found an outlet on stage pent up inside him, he snapped.

Bon got drunker and more agitated, and took it out on the musicians. The musicians responded in kind. Absolutely blind, Bon stormed off, telling everyone to get fucked. This was his dark side, when he didn’t care even for his own safety, when his recklessness became purely self-destructive. Everyone told him, Don’t get on your bike, Bon, you’re too pissed to ride. Bon told them to fuck off. He furiously threw an empty bottle on the ground, and, amid smashed glass, roared off.

The hospital rang Irene in the early hours of Saturday morning. Irene rang Vince Lovegrove, one of Bon’s oldest friends, who lived just around the corner. Calls from his friend at all hours were not unusual, Vince later recalled in the obituary he wrote to Bon, but this time Vince knew something was wrong as soon as the phone woke him. He too had watched Bon ride off into the night.

“I went and picked up Irene and we went down to the hospital,” Lovegrove said. “Bon was a mess. All his teeth were wired up, he was on a respirator, and he was abusing the nurses, abusing them through this respirator!”

A report ran the following day in the News under the headline SINGER INJURED. “Well-known Adelaide pop singer Bon Scott has been seriously injured in a motorcycle accident,” it read. “Scott, who suffered a broken arm, broken leg, broken nose and concussion in the accident at Croydon, is in a serious condition at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital intensive care ward.”

After three days in and out of consciousness, and then four weeks in traction, Irene finally took Bon home. He had almost died; but maybe, as things so often are, the accident was meant to happen. Bon was certainly one to believe in fate. Mobility was central to Bon’s philosophy of life: it was just, keep moving. And here he was laid up with his leg in a cast, with wires through his jaw, resenting the hell out of his condition, but finally being forced to stop and think.

He decided that he had to leave Fraternity, Adelaide, even Irene. He didn’t want to give up on his marriage, but he had to. His calling was somewhere out there on the road, and Irene just wanted to settle down. And while he appreciated the fact that Fraternity had opened his musical horizons after the shallow Valentines, he realized he’d had enough of this serious shit. He wanted to rock’n’roll, pure and simple.

Bon had to find a ticket out.

When he got back on his feet, Vince, who was working as a concert promoter, gave him some odd jobs to do—putting up posters, driving around visiting bands, painting the office. In August, Vince brought a virtually unknown band by the name of AC/DC to town.

It was the answer to all Bon’s prayers.

Vince kept telling Bon how good these kids were, and urging him to come down and have a look at them. They wanted a new singer and Vince had the idea of putting them and Bon together. Bon was skeptical, but he went along to see them one night anyway.

Hobbling into the Pooraka Hotel, Bon had no idea he was staring his future in the face. But AC/DC was everything he could have asked for—a gung-ho young rock’n’roll band in need of a front man. If Bon had any doubts about himself—that he wasn’t fully recovered from the accident, or that at 28 he was getting on a bit—they were swept aside. AC/DC and Bon were made for each other.

Within weeks, Bon was playing his debut performance with the band in Sydney. The Youngs had found the link they were after. AC/DC were on their way.

Inspired though he was, Bon knew it was still going to be a long way to the top, but he was prepared to give everything he had. For the old man, as his new young cohorts called him, it would be third time lucky.