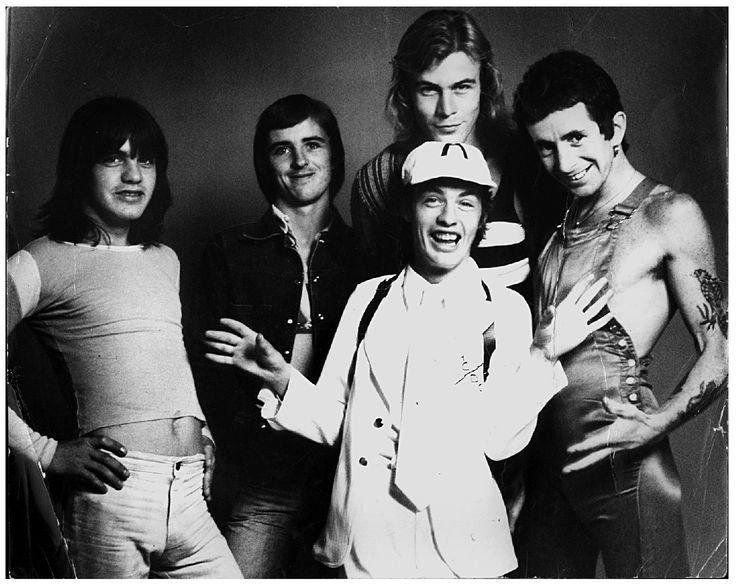

AC/DC begins to coalesce: Melbourne, January/February, 1975. Left to right: Malcolm Young, Phil Rudd, a temporary bassist identified only as “Paul,” Angus Young, and Bon.

Bon: “Fraternity worked on a different level to me. They were all on the same level and it was way above my head.They didn’t have a chance in England. This group has just got it.” (courtesy Mary Renshaw)

9. LANSDOWNE ROAD

Dennis Laughlin was paying AC/DC their wages in drugs and spare change. He wasn’t going to last.

But then, the extraordinary thing about these early days of AC/DC is how so much happened so quickly. Bon joined the band at the end of September 1974. Within six weeks, they were without a manager, but in the studio recording an album. Within six months, with powerful new management and a new lineup, and now based in Melbourne, they would have both a debut single and a debut album in the top ten.

Dennis Laughlin and AC/DC parted company within a few weeks of Bon joining the band. Bon had expected to be based in Sydney, where the Youngs lived, but a management offer from powerful Melbourne player Michael Browning meant that the band would soon move south, although not before they cut the album with George and Harry in Sydney in November. By December, though, the band had set up base in Melbourne.

When Bon first arrived in Sydney in late September he stayed at Dennis Laughlin’s flat in Cronulla. Bon knew Laughlin from when Fraternity used to play gigs at Jonathans, and he liked him.

Bon was mucking around with Malcolm and Angus, comparing musical notes. He was convinced AC/DC could be a world-beater. He was astonished by the musical acuity and empathy of Malcolm and Angus, despite their youth, and he was swept along by their single-mindedness. It was as though he’d been reborn. Any lingering pain from his injuries was overridden in the general rush of it all. And Bon gave something back to Malcolm and Angus in return.

GRAEME SCOTT: “I think Ron put a bit of life into it. I think it was what Malcolm and Angus were looking for.”

“Bon was the biggest single influence on the band,” Malcolm has admitted. “When Bon came in it pulled us all together. He had that real stick-it-to-’em attitude. We all had it in us, but it took Bon to bring it out.”

“When I sang I always felt there was a certain amount of urgency to what I was doing,” said Bon. “There was no vocal training in my background, just a lot of good whisky, and a long string of blues bands, or should I say ‘booze’ bands. I went through a period where I copied a lot of guys, and found when I was singing that I was starting to sound like them. But when I met up with Angus and the rest of the band, they told me to sound like myself, and I really had a free hand doing what I always wanted to do.”

The band played its debut proper, with Bon singing, at the Brighton-le-Sands Masonic Hall. They had to get their shit together quickly because they were due to go out on the road in the second week of October. Laughlin had booked gigs in Melbourne, then over in Adelaide, then back in Melbourne again. Then they would return to Sydney to start recording.

LAUGHLIN: “The biggest problem I had with AC/DC in those early days, being a touring unit, and not having much money, was keeping everything together, keeping everyone happy. There’s a few dope smokers in the band, right? Instead of giving everyone fifty bucks a week, it’s like, alright, whatever you need, we’ll get. Thirty bucks a week plus a bag of dope, a bottle of Scotch. Well, Angus was a pain in the arse, because he says, Fuck ya, I don’t drink booze, or fuckin’ take drugs. I’d give him a bag of fish’n’chips, a Kit Kat, a packet of Benson & Hedges and a bottle of Coke.”

In Melbourne, the band played the suburban dance circuit, some of the new pubs, and the old discos. On October 16, for the first time, they played Michael Browning’s Hard Rock Cafe on its gay night.

From Melbourne, the band headed to Adelaide, where Vince had booked them into the Largs Pier for three nights. Bon was extremely pleased with himself, being back in town with what he believed was the hottest band in the land. However, with the exception of Uncle, who got up one night to have a blow, Bon’s old friends were dismissive, reckoning Bon was selling out to a simplistic three chords. It was the sort of condescension AC/DC faced continually, and would hold against Australia in later years. Bon’s attitude was, Fuck ’em. He trusted only his own gut feelings, and they were good.

Adelaide would be the final showdown for Dennis Laughlin.

MICHAEL BROWNING: “They came down to Melbourne. They had a manager who was a sleazeball. I was just the guy running the club, and I really liked them. They came to collect their money at the end of the night, and told me they were going to Adelaide the following day. So I said, Well, seeya when you get back. Next thing, I got a phone call from Adelaide to say the guy had absconded with all their money or something, and that they were stranded.”

LAUGHLIN: “I got the shits with them one night in Adelaide. Angus was complaining, Oh, Bon’s got a bag of dope, a bottle of Scotch, and I ain’t got nothin’.” So I said, Fuck ya, I’m not workin’ my arse off anymore, here’s your books, you’ve gotta be in Melbourne by one o’clock tomorrow, I’m going home, seeya later.”

BROWNING: “I sent them money so they could come back to Melbourne, so they could fulfil their commitments to everyone, including me. When they got to Melbourne, they came and saw me and we talked about management. I’d only seen them once then, and I just remember being totally knocked out. They had a new singer then too—Bon Scott—and my immediate reaction, I suppose, was a little skeptical, because my image of Bon Scott was as the singer in a teenybopper group, and AC/DC were more of a street rock’n’roll band. But it worked. Malcolm and Angus hated anything that was pretentious, or plastic, poofy, and Bon just exuded character.”

If Bon had liked Dennis Laughlin, he was, however, quite prepared to defer to Malcolm and Angus. If Michael Browning was it, then fine.

Browning himself had been looking for an act to get involved with for the past six months—since May, when he had resigned from managing Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs after five years. “One tends to become a little complacent after such a long time,” Browning explained to Go-Set, but more likely, he was disappointed that Thorpe had failed to give it a serious shot overseas.

George Young went to Melbourne to see Browning, and again was impressed with Browning’s track record, and his ambitiousness. Browning and George shared a vision: George wanted to get AC/DC out of Australia as soon as possible. Browning wanted a band he could take overseas.

BROWNING: “My sole personal ambition to be the manager of an Australian band that broke internationally was a motivating factor in AC/DC’s success. I mean, it was one thing for Alberts to say, We want to break this band internationally, but without someone to come along with the drive, and the game plan, well, it really wasn’t going to happen.”

Michael Browning was, indeed, one of the first Australians to seriously consider going overseas with a band. The first band he ever managed was Python Lee Jackson, which itself made a pioneering foray to England in 1968, only to turn up in America in the early seventies with an album called In a Broken Dream, which featured Rod Stewart on vocals. Browning went on, in the late sixties, to join Bill Joseph at AMBO, at which point he also took on management of Doug Parkinson. Doug Parkinson In Focus was probably the biggest band in Australia in 1969, having hits like “Dear Prudence” and “Hair.” But if Parkinson was never going to go the distance, Browning picked up Billy Thorpe on the verge of his second coming.

By 1973, Thorpe was still a big draw, but his star was descending. Moreover, Consolidated Rock, the Melbourne booking agency Browning had formed with Michael Gudinski and Bill Joseph after the demise of AMBO, had itself folded. Gudinski had formed Premier Artists in its place—the agency that still has a stranglehold on live music in Melbourne today—and then went on to launch Mushroom Records, the definitive Australian label of the seventies and eighties.

Michael Browning was in need of a new initiative, too. The scene offered few immediate prospects, but with a more solid infrastructure now in place it was ready and waiting for a resurgence.

Over the Australia Day long weekend of 1974, Browning trooped out to Sunbury yet again with Billy Thorpe. The whole thing was becoming rather routine. Neither the Aztecs nor Sherbet nor the reformed Daddy Cool delivered anything worth getting excited about. But when a new Melbourne band by the name of Skyhooks took the stage and proceeded to tear it apart, people sat up.

Michael Gudinski jumped first and signed the Skyhooks to both management and recording contracts, and by the end of the year, they’d saved the floundering Mushroom’s skin.

Between that and the new ABC pop program Countdown, launched at the end of the year and fronted by Molly Meldrum, the resurgence was finally on. Michael Browning saw AC/DC and he knew that they could not only be part of it—they could also transcend it.

BROWNING: “No doubt about it. Otherwise I wouldn’t have undertaken it. I mean, I was married, and eventually I had kids and all the rest of it, we dragged them all around the world, and there was no way I was going to do that if the group didn’t have the quality that people now recognize. They were definitely special. And still are.”

AC/DC were not strictly speaking a product of the pub circuit. Nor were Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, Chain, and the Coloured Balls, but AC/DC followed on from them in paving the way for pub rock.

It was a process of infusion. Sharing the same influences (Chuck Berry, blues, boogie, the Stones, a trace of metal), AC/DC played to the same audience Billy Thorpe had found—an audience that was young, male and left right out. An audience that liked its rock’n’roll hard, fast and tough. And loud.

In 1974, these suburban boys had nothing they could call their own. Their sisters had all the poofy pap Countdown could throw at them, like Skyhooks and Sherbet. Their older siblings were bonging on and getting into art rock and California soft rock. To these guys, all that stuff was hippie shit, and they hated hippies.

Heavy metal pioneers like Black Sabbath were already past it. The only new light was Status Quo. Or, if you were really hip, Alex Harvey or Lou Reed. No one had even heard of the New York Dolls. The local scene was an absolute desert. The sharpies (a rat-tailed Australian variant of skinheads) had had the Coloured Balls, but sharpies were dickheads, and the Coloured Balls were falling apart anyway.

It was into this yawning gulf that AC/DC stomped—too late, too ugly to be glam; too clever to be metal; too soon, too dumb to be punk.

They were at once a culmination and a fresh start for the push of what Anthony O’Grady, editor of new Sydney-based rock rag RAM, described as “high energy heavy metal boogie bands.” AC/DC were distinguished, to begin with, by the telepathic guitar interplay between Malcolm and Angus, which determined their unique dynamic texture. Bon added color to movement with his street-smart edge, strangled vocals, gift for narrative, and mischievous sense of humor. George’s sensibility and savvy helped pull it all together.

It was just what the suburban boys wanted.

BROWNING: “There were a lot of suburban dances, the sharpies used to go to them; there were certain dances that were just sharpies. The big groups of the time were Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, and Lobby Loyde and the Coloured Balls. It was a scene, an atmosphere, I’ve never seen anything quite like it. AC/DC came in on the tail end of that. I’d stopped managing Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, and there was this club called Berties, which had closed down, which I was also a part of. I’d been to London to the Hard Rock Cafe, and I thought, Oh, let’s just deck it out and call it the Hard Rock Cafe. So I did that, and that’s where AC/DC came in. They became fairly regular performers at the Hard Rock Cafe.”

George was of the old school that doesn’t believe a band can even call themselves a band until they’ve played at least 200 gigs. The heavy roadwork AC/DC did was as important as anything in shaping them.

ANGUS: “When we started, as a band, I don’t think there was anyone around really that was doing what we did. I think here [Australia] was really what geared it for us; when you first start here, a lot of the places you play all everybody wanted to hear was rock’n’roll, you know. The faster the better. For us, that was great,’cos that’s what we do best. And we were lucky, because of George and Harry, from their time in the Easybeats; they always said that the best time they ever had was just playing rock’n’roll songs, and you know, they said, That’s what you guys are going to do.”

Michael Browning proposed a scheme whereby his company Trans-Pacific Artists, which he ran in partnership with Bill Joseph, would absorb AC/DC’s debts, set them up in a house in Melbourne, provide them with a crew and transport, and put them out to work, covering all their expenses, and paying them a wage. It was if nothing else an entrée to the Melbourne scene.

BROWNING: “Basically, they were broke. They needed an injection of capital, and an infrastructure placed around them, in order for them to continue.”

George decided Browning’s offer was a fair one.

Bon, like Malcolm and Angus, had already signed a recording-publishing contract with Alberts. Hamish Henry had been prepared to give Alberts his rights to Bon’s publishing, but Bon said, Ask them for some money, you never made anything out of me before. So Hamish sold for $4,000. The recording deal Bon signed, calculating back from royalty statements, was for an equal share, as one of five members of the band, of 3.4 per cent of retail. Standard rate today is around 10 per cent; back then, it was around 5 per cent. Alberts has always been known for driving hard deals; no favoritism was extended just because Malcolm and Angus were family.

Before the band were dispatched to Melbourne, they went into the studio with George and Harry and cut what would emerge as their debut album, High Voltage. They were barely roadtested after only six weeks of gigs, but ready or not the market was crying out for them.

It is significant that the first single lifted off the album was a cover of the Big Joe Williams blues standard, “Baby, Please Don’t Go.” Widely covered during the sixties, the song had been in AC/DC’s set almost since day one. Of the album’s remaining seven tracks, at least one, “Soul Stripper,” was credited only to Malcolm and Angus; another, “Love Song,” sounds like a leftover from Bon’s Fraternity days, even though the credit is shared. The remaining five tracks bear the Young/Scott/Young credit which would become so familiar. But to a great extent—and hardly unexpectedly—the album was half-baked. The story goes that the band already had a number of instrumental backing tracks arranged, and so Bon simply dipped into his notebooks full of rude poetry to find lyrics to fit. Drummer Peter Clack was asked to stand down during the sessions; the job was done by session-man Tony Kerrante.

Bon himself later conceded, “That album was recorded in a rush.” “It was actually recorded in ten days,” Angus said, “in between gigs, working through the night after we came off stage and then through the day. I suppose it was fun at the time but there was no thought put into it.”

ROB BAILEY: “Malcolm and Angus would just jam out things, like ‘She’s Got Balls’—it was just two sequences—slap ’em together and away you go. If they worked, Bon stuck some words on them. He used to walk around with lyric books, and they were full of some of the funniest stuff you’ve ever read. You could sit down and read them and just laugh and laugh.”

CHRIS GILBEY: “Because the band was called AC/DC I said to them, Look, we’ve got to call the album High Voltage. So that was the title.”

CHRIS GILBEY: “Bon went away saying, What a great title, High Voltage , we’ve got to write a song called ‘High Voltage.’ Well, they wrote ‘High Voltage,’ but not until after the album was finished, so it was too late to include.

“Then I created some artwork—we were just making it up as we went—I came up with this concept, of an electricity substation with a dog pissing against it. It’s so tame now, but back then we thought it was pretty revolutionary. EMI didn’t want to put it out because of the cover either, they thought it was very much in bad taste. But it came out anyway.”

After finishing the album, the band left Sydney for Melbourne, via Adelaide. They got to Melbourne at the start of December, and holed-up in the Octagon Hotel in Prahran, until Browning found them the permanent accommodation he’d promised. Bon immediately looked up old mates like Mary Walton, and Darcy and his wife Gabby.

AC/DC took off in Melbourne like a rocket. Boring old farts like Daddy Cool and the La De Das didn’t know what had hit them when this snotty young support band blew them off stage.

BAILEY: “It was an exciting time, because we knew the impact we were having. The band sounded right there, we had a pack of very good songs, the act was great, the whole thing was just in your face.”

AC/DC worked continually, anywhere and everywhere.

BROWNING: “It was a mixture of pub type crowds to teenybopper girls to gays. There used to be a big gay circuit in Melbourne. Bon used to camp it up, he’d wear his leather stuff, and they fitted into that scene quite well.”

“I remember I first saw them when they were still kicking around Melbourne,” said Joe Furey, who later became a friend of Bon’s. “There must have been about a hundred people there, and there was this little guy rolling around the floor playing guitar, and the whole thing was exceptionally loud, it was about one o’clock in the morning, and everybody was sort of going, Oh, give us a break, it’s late. That was one thing I always admired about them, Angus in particular, was that there was a guy who had his act, and whether there was a hundred people there at one o’clock in the morning or what, he was going to do it. It wasn’t like, Hey, there’s no one here tonight guys, let’s cut the set a bit short. Years later I thought that was probably the difference between them making it and not.”

If Bon felt any physical strain from his accident, he didn’t let on.

DARCY: “He was in pain. Those early gigs with AC/DC really stuffed him up. Once you’ve broken something, it’s never the same again. He had to be jumping around singing his heart out, you had to wonder, How’s he going to hack the pace? People wouldn’t see him to the side of the stage hitting his puffer.”

Juke magazine, which sprang up in Melbourne after Go-Set folded, called AC/DC “new faces refusing to be restricted by an established music scene . . . brash and tough, unashamed to be working at a music style that many describe as the lowest common denominator of rock music, gut-level rock, punk rock.”

The story went on to describe Bon, “an old face,” as “charged by the unleashed drive in the group around him, as determined as the rest to have a good time on stage and off, as determined to shake Australian rock where it matters . . .”

Juke was taken aback by “these red-blooded young studs”: “AC/DC quite obviously are not lax to take advantage of the favors in the offering from some of their more ardent female fans. The adjoining motel room was busy with extra bedding and bodies.”

The party had started.

The band moved into a house in Lansdowne Road, East St Kilda. Malcolm and Angus had never lived away from home before, and so at the ages of 22 and 17 respectively, they were running amok, free to come and go as they pleased, to smoke and drink and swear and carry on. And fuck chicks.

ROB BAILEY: “That place was a bit of a madhouse. A really big, beautiful old house, it had a flat out the back, with what I’m sure were hookers living there. You’d wake up in the morning and there’d be bodies strewn all over the place, nothing left in the fridge . . .”

Bon divided his time between the house and Mary Walton’s flat in Carlton. He and Mary had consummated their old friendship, since both their marriages had dissolved. But as much as Bon needed that retreat, he also joined in the fun and games down at Lansdowne Road. He wasn’t going to be denied his second youth.

Over Christmas 1974, AC/DC was out on the road in South Australia.

BAILEY: “We had this Ansett Clipper bus, we’d put the PA in the back, but every trip we did, it would break down. It was supposed to be the logistical answer to all the problems we had, but it just became a bigger logistical problem.”

Spending Christmas in desolate steel town Whyalla might not have been so bad for Malcolm and Angus, because everything was so new to them, and besides, they had each other. But Bon was hit by it. He thought of Irene, and where he found her he found Graeme, because Graeme had taken up with Irene’s sister Faye, and they all lived together in Adelaide. And he thought of his folks in Perth, and his other brother Derek, who had a couple of kids by now.

So he had another drink, and rolled a joint. Bon had made his bed, he accepted that, and he knew these little pangs of longing would pass. The Youngs were his surrogate family now, and the music, to borrow Duke Ellington’s phrase, was his mistress. And he could always count on the music’s transcendence. The band was starting to find, and define (if not in so many words) its own identity—and self-discovery is an exhilarating process.

As part of that process, however, Malcolm and Angus decided the rhythm section had to go. Peter Clack just wasn’t good enough, and Rob Bailey, while he played well, insisted on having his wife with him all the time. And that was a pain in the arse. Besides, he was too tall.

On returning to Melbourne in January, Bailey and Clack were separately summoned by Bill Joseph and given their marching orders. Russell Coleman, former sticks man with Stevie Wright, sat in for a few weeks before Phil Rudd joined. Rudd, nee Rudzevecuis, had been playing behind singer Angry Anderson in latter-day Melbourne boogie band Buster Brown. Erstwhile Coloured Ball Trevor Young (no relation) told him about AC/DC’s vacancy, and he would become the band’s secret weapon, a rhythm machine that created the space within which Angus and Malcolm could move around.

Finding a new bassist proved more difficult. One guy lasted all of a few days. “It’s a pretty rare type of bloke who’ll fit into our band,” Bon told RAM. “He has to be under five feet six. And he has to be able to play bass pretty well too.”

Meantime, the band would play as a four-piece, with Malcolm on bass.

Late in January, George flew down to Melbourne to discuss with Browning plans for the release of the single and the album, and to fill in on bass when the band appeared at Sunbury.

Sunbury was a big part of Browning’s marketing strategy. He had seen the reach the festival could have, even though it was declining fast, and he wanted to use it as a launch pad in the same way Skyhooks had the year before. But this year the whole affair was a disaster, one that spelled the end of Sunbury, in fact. Deep Purple had been flown in as an exclusive international attraction; and, as Michael Browning put it, they just jerked everybody around, especially AC/DC. First Purple said they wouldn’t play, so AC/DC had to be located in Melbourne and dragged out to the site to deputize for them. Then they changed their mind. Angus remembers being disgusted when AC/DC arrived backstage to find one of the two caravans reserved exclusively for Deep Purple, while all the Australian bands had to share the other one. Then, when Deep Purple finished their set they refused to let AC/DC follow them. In response, AC/DC simply took the stage as Deep Purple’s crew was still pulling down gear. A full-scale brawl ensued, on stage, in front of 20,000 people.

BROWNING: “What really pissed me off on that occasion, and what really made it clear I had to get AC/DC out of Australia, was the fact that the local crew people actually sided with Deep Purple.

“It just really brought home how subservient Australians were to anyone from overseas. How if you really wanted to gain respect you had to go overseas.”

The High Voltage album and “Baby, Please Don’t Go” single were released simultaneously in February 1975, with the Hard Rock Cafe throwing a “Special AC/DC Performance, New Album, Adm. $1.00.”

Rob Bailey was shocked to discover that his work on the album had not been credited. But then the packaging of High Voltage gave precious little away at all (and when it did, incorrectly attributed “Baby, Please Don’t Go” to Big Bill Broonzy). The story that got around was that George played bass on the album, though that story is still disputed by Rob Bailey, who certainly has never seen any money from Alberts.

Critical consensus, such as it was, had it that High Voltage was, indeed, premature. That’s when scribes weren’t simply damning AC/DC as altogether rude, crude and uncalled for. But certainly the single, with its driving arrangement reminiscent of Golden Earring’s 1973 smash “Radar Love,” looked set to do business.

Mark Evans joined the band just after the record’s launch. Evans, born in Melbourne in 1956, was working in the public service at the time, living with his mother in a council flat in Prahran and just mucking around on bass. There is no truth in the myth that Evans’ introduction to AC/DC came when Bon stepped in to save him from copping a hiding off the bouncers at the Station Hotel. In fact, he was mates with one of AC/DC’s roadies, who told him about them.

MARK EVANS: “I just went down and saw them—Malcolm was playing bass then—and they gave me a copy of the album, I took it home, thought, Okay, that’s fine, auditioned—straight in.

“That’s all it was. I think it was more the look I had than anything else. I don’t know how many times people would find out there was two brothers in the band, and they’d think it was Malcolm and me.

“At that stage, the band was on the bones of its arse. Like, I remember at one stage, Phil even running out of drumsticks, so we had to go and get pieces of dowel from the hardware store and fashion them into drumsticks.”

But it wasn’t long before Evans was convinced to quit the public service.

EVANS: “We had this roadie called Ralph, and he drove me home in the bus after I’d rehearsed with the band once, and he said, Oh yeah, things are looking pretty good, we hope to be in England this time next year. The whole arrangement for the band was to get out of Australia. And I remember thinking, Yeah, sure! But once I’d spent a month with them, I realized they were dead serious. One thing I will give them, they had an absolute solidity of purpose.”

Still, it would be some time before Evans met Bon.

EVANS: “The audition was held in their house at Lansdowne Road. Bon wasn’t there, I didn’t actually meet Bon until the first gig. He was never at rehearsals. But I knew his name, I kept on hearing about Bon, and I knew, I’d seen the Valentines when I was a kid, at a concert, and I thought, That guy was called Bon, I wonder if they’re the same one. I had this suspicion who he was.”

The scene at Lansdowne Road was one of pure debauchery. AC/DC encouraged every kind of rock’n’roll excess Melbourne had to offer—and Bon, Ronnie Roadtest, would again come very close to going over the edge.

EVANS: “Bon’s personality, and demeanor, would lend him to getting into areas where he would endanger himself. Just from, I’ll try that! And just being lonely, I think, just being isolated.”

Bon offset the deeper rapport he shared with Mary Walton with the pleasures of the flesh available down at Lansdowne Road.

EVANS: “A huge amount of women were hanging around, the only thing that kept [the band] going was the girls that would come around.”

Trudy Worme was one of the teenage girls who was in love with Bon: “I used to visit the guys frequently at Lansdowne Road, tidying up for them and having a lot of laughs. And that’s all it was, too—we were most definitely not into the groupie scene, although several other female visitors were! I used to bake these chocolate cakes, mainly for Angus, every time we called in—it was greatly appreciated as there was rarely any food in the house. My mum used to drop us off and pick us up on our Sunday afternoon visits. My mother had full trust in Bon and the other guys—she considered them a lot safer than ‘real boys,’ the ones our age from school who she thought had more than music on their minds. Angus was only a year older than us, but anyone who liked chocolate cake so much and didn’t drink was okay in my mother’s eyes.”

It was the groupie scene that inspired “She’s Got the Jack,” though it’s ironic that the song places the blame on a woman when it was the boys in the band (or so the self-proclaimed legend goes) who were always running off to the clinic. Bon was well aware of the inflammatory nature of the song. When he wrote to Mary in April after she’d gone to London, he admitted it “may get us castrated by Women’s Lib,” and the recorded version also predicted an outraged crowd reaction.

For all the party atmosphere, though, Malcolm and Angus were deeply suspicious of outsiders—other than chicks, of course. It was part of the clan mentality. Their approach was all or nothing: if you weren’t with them, you were against them. As RAM editor Anthony O’Grady described it: “You’d say hi to them and they’d look at you sideways like, Whaddya sayin’ hi to me for?” Bon was accepted as one of the family, a blood brother, and Mary remembers they were “very, very tight initially.” Malcolm and Angus looked up to Bon as older, wiser and braver. Bon, for his part, was protective of Malcolm and Angus, but he felt more like a conspiratorial uncle than a father figure.

Mary remembers feeling a bit like mum and dad to them. “They were still just babies, and they’re sort of so straight in a way too. Angus didn’t drink, at least not until his eighteenth birthday, when he got totally blotto, and I don’t think he’s ever had another drink since.

“They were so family oriented. They would go and buy a roast, a leg of lamb, and they’d bring it around and ask me to cook it. Because they just missed that home life, I guess.”

Angus once said “Bon gets the women with flats who cook him dinners.” To which Bon replied, “I like to put my feet up. Not to mention other parts of my body. They say to me, Are you AC or DC?, and I say, Neither, I’m the lightnin’ flash in the middle.”

Bon’s code in life was like his attitude to money: if you got it, spend it. Don’t expect it to last, don’t expect it, period. This was his bravado. He sometimes didn’t even seem to fear for his own safety.

Mary was in no position to carp, but when Bon took up with a young girl called Judy King, well, her response was to book a ticket to London. Judy King was an innocent set on a path of self-defilement. Maybe Bon liked the idea of bringing home a beautiful bird, and just a chick at that, with a broken wing. But maybe the attraction was more basic, as Darcy put it: “I just think he did his balls over her, she was so young and fit and tight.”

Bon may or may not have met Judy before she showed up at a gig AC/DC played down the coast at Jan Juc—she was, after all, the youngest daughter in the same King family that Vince Lovegrove had briefly boarded with in 1970. At that time, she was a promising prepubescent athlete, a sprinter. In 1975, at 17, she was an accident waiting to happen.

Within a couple of days of seeing AC/DC, Judy had hitchhiked to Melbourne. Bon was there, and so was her older sister, Christine, who was working in a massage parlor and maintaining a heroin habit. There were also a couple of other girls hanging around the band who would skip school to do afternoon shifts in a parlor in Richmond. Within weeks, Judy too was on the game, sucked into the vortex, complete with a heroin habit of her own. But if Judy was a working girl, she saved her best for Bon. That she was stoned all the time could be a bit of a drag, but she was caught in the classic vicious circle—she worked to make money to buy dope to make work bearable.

The affair flared up for the first time when Bon was hauled in by the cops to account for a stack of allegedly pornographic photographs. Phil, a shutterbug, had taken some shots of Bon and Judy rolling in the hay.

“One morning,” Bon told RAM, “I was in bed—completely out of it—and the chick who was living with me at the time was trying to hitch to work—also completely out of it—well, she got picked up by the police and she’s so gone she can’t speak. [The police were familiar with the house.] So they drive her back and run through the place . . . and what happens but they bust me for pornography!”

Bon was pushing his luck.

“Baby, Please Don’t Go” was starting to sell.

AC/DC enjoyed the support of radio and Countdown. Ever since “Evie” had been broken by 2SM the previous year, radio’s faith in rock’n’roll had been somewhat restored (if only briefly: the arrival of FM later in the seventies saw it turn back to “classic rock”).

Countdown rose in tandem with the music’s renaissance. Coinciding with the arrival of color television in Australia, Countdown quickly became “all-powerful,” as Chris Gilbey put it: “the driving force behind making a hit single.” At its peak, the show had a fair whack of the country’s population watching it. “It was a tough call,” said Gilbey, “because it was very much Melbourne, very much Molly.”

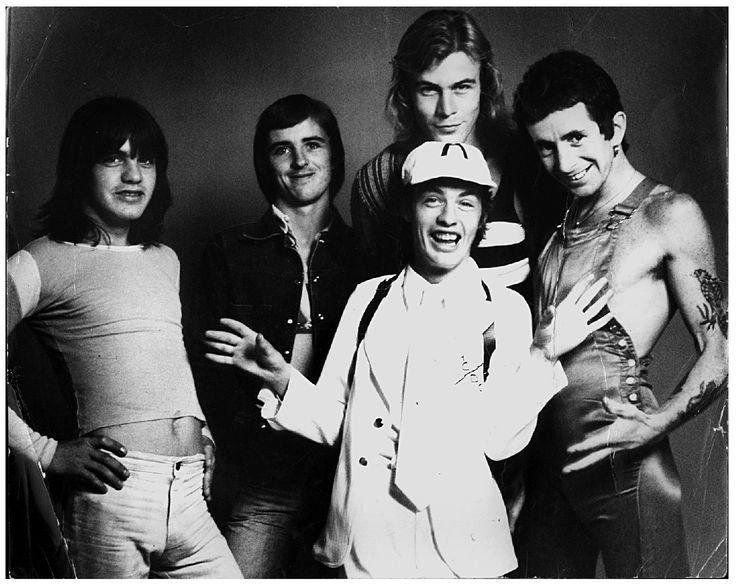

Bassist Mark Evans joined AC/DC in March 1975, completing the band’s classic lineup. L-R: Malcolm, Bon, Angus, Phil Rudd, Evans. (Philip Morris)

Molly Meldrum and Bon knew each other from way back, of course, though their relationship was always awkward. Molly had been a Zoot, not a Valentines groupie. Much later, in 1978, Bon said to RAM, “If you don’t show your arse to Molly Meldrum all the time here, you’re fucked.” But when Molly first saw AC/DC, at one of the Starlight gay discos, he was knocked out, as many people were. And, of course, Countdown too got value out of AC/DC.

But as much as AC/DC were becoming part of the Melbourne scene, they would always be interlopers. That they were for the most part native-born Scots, who would soon enough virtually renounce Australia altogether, was the least of it. Nor was it the fact that they were by rights a Sydney band that made them so unusual, because Sherbet, Hush and the Ted Mulry Gang were also Sydney bands. (Melbourne’s status as pop capital was because of Countdown, its live circuit, and Michael Gudinski’s growing power. But it was one of the ironies of Countdown’s early days that apart from Skyhooks much of its talent was effectively bussed in from Sydney, including also Marcia Hines, Jon English, William Shakespeare and John Paul Young.)

In any case AC/DC were like a cat among the pigeons on Countdown—rough and ready, for real. Sherbet were clearly little more than froth and bubble, and while Skyhooks were always likely to be “outrageous,” they were also playing down to their audience. But what really distinguished AC/DC was the sense they gave that they were just passing through, that all this was just a stepping stone to bigger and greater things. It was obvious even then that such favorites of the moment as Sherbet and Skyhooks would never surpass their Countdown heights. But AC/DC had something more.

Back in Sydney, Alberts was well pleased with itself. Cabal-like even in its hometown, it had penetrated Melbourne and its mafia. Alberts enjoyed an incredible reign during 1975-76, when you would sit down to watch Countdown every Sunday night (along with virtually every other household in Australia), as the show lurched forward, coughing and spluttering and glittering—and if you didn’t love it, you most certainly loved to hate it.

After “Evie” put George and Harry back on the map, they followed up this success at the end of 1974 with William Shakespeare, a sort of cross between Gary Glitter and Pee Wee Herman, who scored two consecutive number ones with “My Little Angel” and “Can’t Stop Myself from Loving You.”

AC/DC, with their long-term potential, would become Alberts’ flagship act, but Alberts had other fish to fry, too—and these were bigger in the short term. Between AC/DC, John Paul Young and the Ted Mulry Gang, AC/DC was the only act not to score a number one before 1975 was out.

CHRIS GILBEY: “It was an incredibly exciting period. Alberts was so small, it wasn’t like a big record company. We were just making up the rules as we went along. And everything we put out became a hit.”

John Paul Young’s disco-pop sound was as different from AC/DC as anything could be. George and Harry wrote and produced his material, which only confirmed their range. “Yesterday’s Hero” hit number one in April; “Squeak,” as Molly Meldrum dubbed John Paul Young, would go on to produce a string of hits. Chugalug boogie merchants Ted Mulry Gang, produced by Ted Albert himself, had been on the road even longer than AC/DC—often with AC/DC—when in November, their second single, “Jump in My Car,” went to number one.

This was good, George thought. He liked to work, just as much as he liked to drink; both of which he did with a peculiarly Scottish zeal. The studio at Alberts was finally finished, complete with a 16-track mixing desk shipped over from England. George and Harry spent every waking hour there.

Appearing on TV show Countdown changed AC/DC’s audience. The mixed crowd the band had attracted to its live gigs was driven away by the onrush of screaming teenyboppers. Not all the little girls, after all, could swallow the smarmy Skyhooks or Sherbet, or Abba, the Bay City Rollers or Peter Frampton. There were plenty of tough chicks to whom AC/DC’s rough and ready image appealed immensely. “They were everything the Bay City Rollers didn’t stand for,” said RAM. “Maybe it was the way [Angus Young] jumped and rolled around stage like a demented epileptic while not missing a note of his guitar duties. Maybe it was the way Bon Scott leered and licked his lips while his eyes roamed hungrily up and down little girls’ dresses.”

MARK EVANS: “They could see, I guess, there wasn’t any bullshit involved, like high heels and make-up.”

Teen fandom is totally partisan, of course, but only to the same degree that it is transient. The difference between AC/DC and Sherbet or Skyhooks was that AC/DC had the vision for longevity. Skyhooks may have been the first Australian band to write hit pop songs that had overtly Australian flavored lyrics, but AC/DC went beyond the literal. They had a deep-seated originality that has stood the test of time.

AC/DC would outlive teen pinupdom because when the little girls abandoned them—as the little girls are wont to do—the boys came back. This to the band was a transient phase, as Australia itself was—a stepping stone to greater things.

At the end of March, as both the single and album entered the charts, and AC/DC were playing a good eight gigs a week in Melbourne and elsewhere, Bon’s relationship with Judy King came to an ugly climax.

Smack was never far from the surface of the seventies rock scene. Most people still came on like hippies, but the heady days of communal tripping were over. The me-decade demanded a more self-centered high. Harder drugs came in: at the up end of the spectrum, cocaine and speed; at the down end, heroin. No less an icon of cool than Keith Richards was a brazen junkie.

Bon’s drinking had been on the increase ever since he joined Fraternity in 1970. As AC/DC progressed, Bon consumed more of everything. His drinking could be on and off—he was a binge drinker really—but the grog was a persistent presence. And smoking pot was a habit he never kicked, never saw the need.

But if there’s ever been a suspicion Bon was more deeply involved with narcotics than it seemed, the fact is that he never really got into heroin. Certainly though, he dabbled in it, as Judy King went down on it. On at least one occasion, in Melbourne in early 1975, he almost died of an overdose. But that, it seems, was enough to warn him off it, even though heroin would surround him and touch him as a codependent for the rest of his life.

Until the Vietnam War, heroin had been only a minor presence in Australia, mainly in Sydney’s Chinatown. In the early seventies, though, the drug spread out of Kings Cross. Supply reached Melbourne, where it flowed through massage parlors and hamburger joints on Fitzroy Street, St Kilda.

Judy King was working in the parlor and spending every penny she earned on smack. One night, Bon found her and Christine out of it as usual. But rather than just being on the nod, they were in high spirits, mischievous as sisters can be. They began goading Bon, trying to entice him to have a taste. Of course, if there was one thing Bon couldn’t resist it was a dare, even if it went against his better judgement. He rolled up his sleeve.

The girls tapped out a measure of brown rocks into a spoon. Adding water and a dash of lemon juice over a match, the heated mixture dissolved. Judy drew it into a syringe through a filter from a cigarette. Bon took off his studded belt to use as a tourniquet. Judy found a vein, which wasn’t difficult on Bon’s sinewy arm, and shot him up.

Bon felt the warm, sickly sweet rush—and then . . . nothing. He slumped in his seat. He had no tolerance, and he was small-framed, too. He turned a hideous blue-gray color. But he was still breathing. Judy was hysterical. Stoned as she was, Christine thought quickly enough to shoot Bon up with some speed in an attempt to negate the heroin. She moved in a panicked sort of slow motion, fumbling with the syringe, having difficulty finding the vein without any tension left in Bon’s body. When she did, he let out a whimper, but that was all. It wasn’t enough. An ambulance would have to be called. The girls did so. As they waited, a scared Judy paced the room as Christine gave Bon mouth-to-mouth and massaged his heart.

When you overdose on heroin, it is a near-death experience, but it has no romantic qualities. There’s no light, or St Peter waiting at the gates, just a falling into a deep gray void. Your life does not flash before your eyes. You are not privileged with the opportunity to repent for your sins.

Bon sat bolt upright into consciousness when the ambulance officer revived him. He felt like he had been set rigid in cement, alive, looking out, but hit so hard upside the head he didn’t know where he was. Certainly, he had no immediate past. Then he remembered, and that was the worst part, when he looked up and saw the scene: Judy in tears and Christine relieved, the ambulance men packing up their gear and shaking their heads. He remembered everything, and he felt so bad.

Later in life, Bon resented forgetting. After his body and mind had taken so much for so long, his memory, both short- and long-term, was eroded. Remembering may be bad, but not being able to remember was worse. When he was younger, though the pain was sharper, his body was also stronger, more resilient. The spirit, spunkier.

Bon didn’t blame Judy. But if this was a case of his non-judgmental attitude getting the better of him, he was about to have the illusion literally beaten out of him.

In a report in Melbourne’s notorious Truth newspaper, under the headline, POP STAR, BRUNETTE AND A BED: THEN HER DAD TURNED UP!, Bon told Dave Dawson: “The girl’s father had warned me once before not to sleep with her. But she is 17 and capable of making up her own mind. I had returned from Sydney the night before and she was there waiting for me. We were making love when our roadie Ralph knocked on my bedroom door and said someone wanted to see me urgently. I told him to come back in two hours because I was busy. Eventually I went to the door and was sprung by the girl’s father. I was wearing only shorts. He said, I can see you’ve got your fighting shorts on. He took out his false teeth and said, Come outside.

“I followed him outside where he had two of his mates aged in their 30s. He said, Where’s my daughter? I said, She will have gone by now. You are always bashing her up. Suddenly, he started punching me in the head and body. He knocked me into a rose bush and dragged me through it. Then his two mates came over and dragged him away. They could see that because I was just 5’ 5” I didn’t have a chance.

“That was the worst beating I have ever had. My manager Mike Browning took me to a dentist who couldn’t stop laughing when I explained how my dental plate was smashed and my teeth were knocked out. It wasn’t so funny for me because the dental bill will be at least $500.

“The girl’s father has never given her any love and he certainly showed me none.

“After he bashed me he said, If she is not home by night I will send another ten blokes around to bash you. I’m certainly not going out of my way to see her again.”

Eerily, Bon had almost predicted this incident in the lyrics of Fraternity’s “Annabelle.”

Annabelle’s got problems,

The doctors can’t repair . . .

When her daddy gets here,

He’ll come knockin’ on my door,

The next thing I replace

Bear-skin rug on the living room floor.

Bon was in disgrace.

In April, AC/DC played two momentous shows in Melbourne as “Baby, Please Don’t Go” peaked at number ten nationally. The High Voltage album also reached the charts, where it stayed for an unprecedented 25 weeks. Overseas, Michael Browning’s sister Coral was sniffing around.

Coral, who’d met the band in Melbourne earlier in the year, was based in London, where she was well positioned in the music business, working for the management company that handled Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Gil Scott-Heron. She was very enthusiastic about her brother’s new charges.

AC/DC’s staple Hard Rock gigs in Melbourne remained. On Sunday, April 13, the band played a “Heavy metal rock nite” with the Coloured Balls; the next Saturday, with Richard Clapton. The very next day, they played bottom of a big bill on a Freedom from Hunger show at Myer Music Bowl. The following week, they supported the Skyhooks at Festival Hall.

It was a freezing cold Melbourne Sunday, but in spite of that, 2,500 still showed up at the Music Bowl. They paid $3.50 or $2.50 to see the Moir Sisters, Ayers Rock, AC/DC, Jim Keays, the La De Das and Jeff St John with Wendy Saddington. AC/DC, as one newspaper report read, “got the best audience response . . . As they walked off the stage at the end of their set, nearly half the audience decided to leave as well.”

“Sure surprised us,” Angus said in RAM. “Everyone always told us we were shit compared to real bands like Ayers Rock.”

Perhaps as a gesture of appreciation, AC/DC were presented after the show with supergroupie Ruby Lips. A good time was had by all, so much so that Bon later eulogized Ruby Lips in Let There Be Rock’s “Go Down.”

But not even success opened AC/DC up. Quite the opposite, in fact. Countdown was an opportunity for bands to get together—when they were all busy working by themselves they seldom saw each other—but AC/DC didn’t fraternize with other bands. Malcolm and Angus always regarded themselves as separate, if not superior, to other bands. Bon would often go off on his own and meet other people, but when he was with the band, even Bon hesitated to break formation.

MARK EVANS: “We hated everyone as a matter of policy, the same way we hated hippies. No other band existed, except for maybe the Alex Harvey Band. Little Richard. Chuck Berry. Elvis. But no one admitted it. We just didn’t even talk to other bands.

“Bon could get on with anyone, but Angus and Malcolm had this incredible tunnel vision where no one else counted. It must have had an effect on Bon too. There were times, I’m certain, when Bon would have gone home and said, Fuck this, I’m not putting up with it anymore.”

Being so antisocial was against Bon’s natural inclination, after all. He had acquired the nickname Bon the Likeable, after Simon the Likeable, a character on Get Smart whose secret weapon was that he was impossible to dislike.

MARK EVANS: “My mother was in love with him. He’d come around for dinner and say, Can I do the dishes?”

AC/DC’s aloofness and arrogance was partly due to well-placed self-belief—a quality any artist needs to become great. But it was also a mask for something more troubling—an insularity that bordered on paranoia. It was an understandable defensiveness at the resentment, if not contempt, so often directed at AC/DC; but it was also a shield for insecurities. Maybe due to their sheltered upbringing, maybe just because of their lack of education, Malcolm and Angus were not blessed with many social skills. They were not articulate and were wary of other people. The family had always provided for them, and they saw little need to step outside it now. Bon had to skate around such obstacles.

The band played with Skyhooks at Festival Hall. “Needless to say what happened,” said Bon cockily in a letter to Mary (AC/DC especially hated Skyhooks). Opening band Split Enz were booed off stage. “Only the little fellows of AC/DC really pulled it off,” reported the Sun.

Bon wrote further to Mary:

I’ve been in the badbooks with everybody lately & I’m really such a nice person. I just don’t understand . . .

Off to Sydney on the weekend for a couple of weeks. Life is so boring in Melbourne, still no word on Europe but it shouldn’t be too long. I reckon before Xmas or we’ll all go fuckin’ mad. We just keep copping the same shit week in and out. We feel like packin’ it in and going to Sydney and spend all our time putting down songs in Alberts. The rest of the country’s fucked. Don’t I sound like a bloody whinger. Grrr!!!

The band had started dropping into Alberts on their Sydney visits. They were eager to start recording again, now that they had a proper line-up and even had a few song ideas. AC/DC never rehearsed, as such, but Malcolm and Angus would sometimes sit around together with acoustic guitars. Bon had his notebooks, and he was scribbling away—if scribbling’s the right term because his handwriting was extremely neat.

Bon wrote to Irene:

Times is tough at the moment cause Caruso ’ere ’as lost ’is vocal sound, know wat I mean. Worked so hard this last few weeks, it’s just said, Fuck you lot I’m havin’ a rest. Had to cancel a week’s work but because we’re in Sydney we can spend all our time in Alberts recording our next smash . . .

I miss ya sometimes ’Rene. Strange that comin’ from me but it’s true. It’s probably the weather.

Bon was obviously still feeling a little sorry for himself. There can’t have been much money around either, as Bon concludes the letter with a PS to Graeme: “If you can still manage the other $50 I’d love ya f’rever. It’s no fun waiting round to be a millionaire!!!”

During the May school holidays, AC/DC played a special “Schoolkids Week” of daytime gigs at the Hard Rock. It must have seemed a lot like déjà vu for Bon, being back under siege at the club that had previously been Berties.

MARK EVANS: “Because it used to be so packed downstairs, we used to get changed in Michael’s office, which was right by the front door, go out on the street, unscrew the air-conditioning ducts and we’d go in through there; they’d close them up after us.”

On the Queen’s Birthday holiday in June, in anticipation of the release of a new single, “High Voltage Rock’n’roll,” AC/DC played, for the first time, their own headline show at the Melbourne Festival Hall. Stevie Wright and John Paul Young supported. The concert was filmed, and it was this footage, with judicious doctoring, that would effectively argue the band’s case in England.

CHRIS GILBEY: “We did a video, this was before videos were the norm. I was pushing Ted, We’ve got to do videos. I wanted a video of AC/ DC, and I wanted it to be something really sensational. Anyway, we shot it, it was live, they used four cameras, which was unheard of then, it was quite a big budget. And then we added applause at the beginning and end, which we took off the George Harrison Concert for Bangladesh album, to make it seem like it was live.”

The gig itself marked AC/DC’s conquering of Melbourne. It had taken just over six months.

Bon wrote to Irene:

HV (LP) has made a gold album (last week) so it caused a slight celebration. I’m going to give it to mum. So I told her to make a space on her mantelpiece. She told me to write some clean songs for the next one but. Wait till you hear a couple of ’em. The band is nothing like it was when you heard it last. Got a couple of better players, better equipment, and songs, just better all round. So watch out.

With Melbourne in the bag, and the lease up on Lansdowne Road, Sydney was beckoning. Bon wrote to Mary:

I think we’ll be living in Sydney soon and try to get the band as big up there as we are down ’ere. We all prefer Sydney to Melbourne but we wish we could drop in and see you over there instead. This country’s driving us sane.