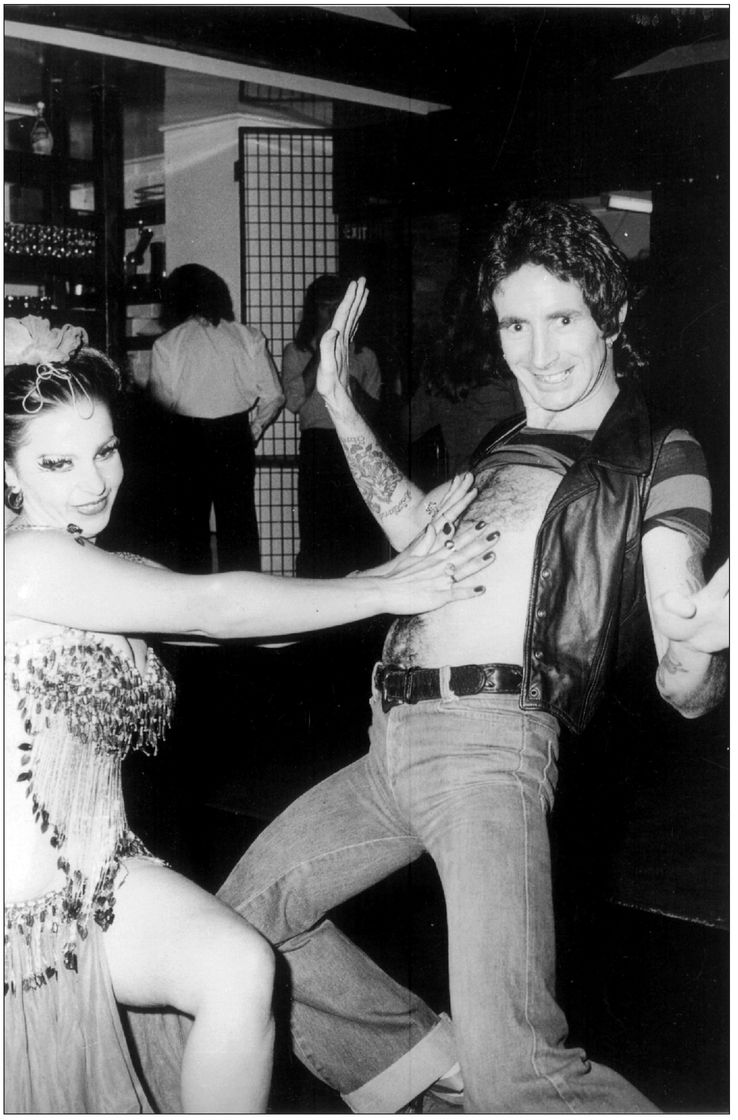

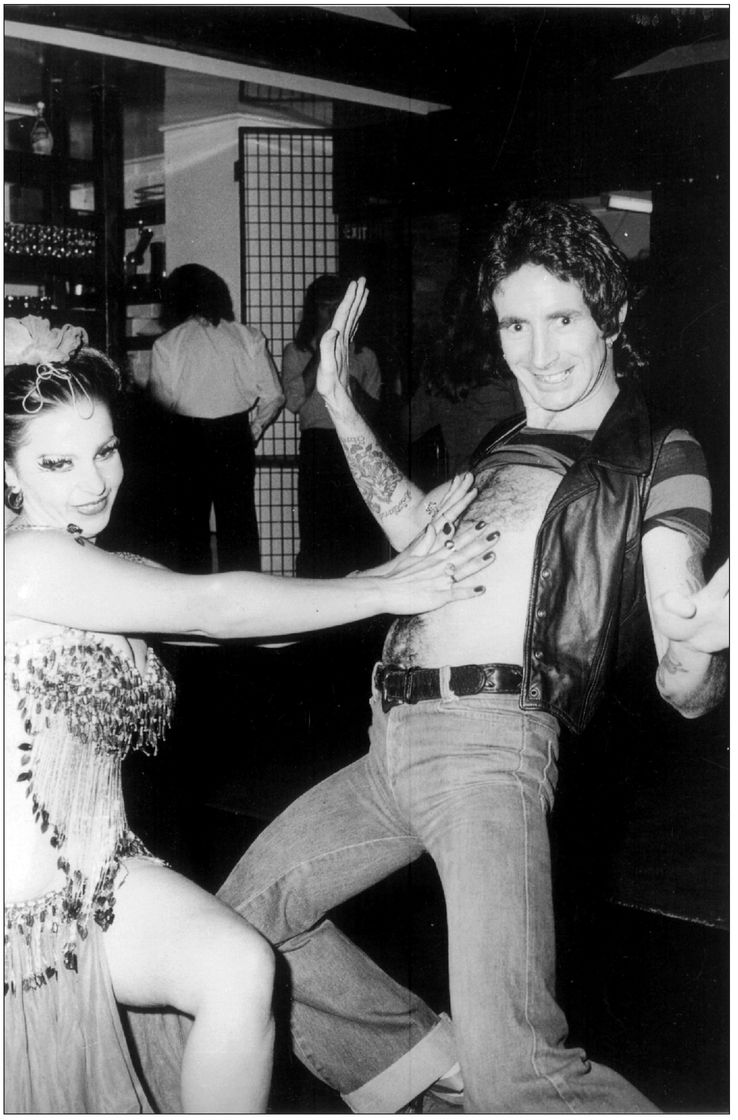

(Roger Gould/Juke)

EPILOGUE: BACK IN BLACK

On Countdown Molly Meldrum was spouting that Stevie Wright would replace Bon in AC/DC. It seemed an obvious conclusion to jump to, but Alberts quickly stood on it. “We don’t know where he got that from,” a spokesperson said, “but there’s absolutely no truth in the rumor. Stevie’s got his own thing to do, and AC/DC have theirs.” Stevie’s “thing” was his heroin addiction, which had effectively seen him frozen out of Alberts altogether.

Molly himself was attacked for tastelessness in even raising the issue of a replacement. “That’s just absurd,” he snapped back. “I’ve known Bon for 12 years, longer than most of these other people who found it tasteless, and I know he wouldn’t have minded. Life goes on; if I dropped dead, I’d expect Countdown to announce a replacement immediately and keep going.”

And indeed, as soon as Malcolm and Angus returned to London from the funeral, they “got straight back to work on the songs [they] were writing at the time it happened.”

Given the band’s deep suspicion of the press it was amazing, as Dave Lewis wrote in the Sounds feature “The Show Must Go On” of March 29, that “the ever articulate Angus allowed himself to become the band’s spokesman at a time when many others would sulkily shun the glare of publicity.” But Peter Mensch wanted it to be known that AC/DC would not fold—were in fact auditioning new singers even then.

Bon meant little to Mensch personally; his primary concern was simply that the band’s momentum was not lost. And everybody, Bon included, had believed this next album was going to be the one. For Malcolm and Angus, their supreme ambition was a bulwark against grief. Besides, they had been granted the highest approval. When they were leaving the funeral, Malcolm has recalled, “Bon’s dad said, ‘You’ve go to find someone else, you know that.’ He said, ‘Whatever you do, don’t stop.’” Quitting the band would have been the travesty, not continuing it, and Bon himself would have expected no less.

“We got a little rehearsal studio and songwriting became our therapy,” Angus said. “Then our manager kept pestering us about what we all dreaded: don’t you guys want a new singer? We kept putting it off . . .”

They can’t have resisted too strongly: after getting back to work two days after their return to London from Bon’s funeral, they were auditioning singers within a couple of weeks; within a month, they’d settled on Brian Johnson, and within six weeks, they were in the Bahamas recording Back in Black. If leaping back into the fray with their blood brother still warm in the ground seems in any way graceless, well, no-one ever called the Youngs great sentimentalists.

What was perhaps even more extraordinary, though, was that they made it work. Where bands like the Doors—and later Nirvana and INXS—failed, AC/DC succeeded, and then some. Not only is Back in Black the greatest resurrection act in rock history, it is one of its biggest selling albums.

The gift in all this was Bon’s anointing. Bon’s generosity of spirit, even in death, outdid anything most people could muster in life.

In their Pimlico rehearsal room, Malcolm and Angus worked over song ideas. It was a bit weird without Bon, but they could still hear him, ghost-like, when they got really pumping on a riff. Even in absentia, he was still, as he himself had said, “the lightning bolt in the middle” that charged the two poles on either side.

Alberts’ Fifa Riccobono announced, “Nine names have already approached them for the job, although of course I can’t say who they are. It will be quite a gap to fill, but the band will be auditioning lead singers almost immediately.”

Speculation was rife. Melody Maker ran with the Stevie Wright rumor; NME and Juke suggested it would be one Allen Fryer. Fryer, erstwhile front man with a small-time Adelaide band called Fat Lip, was George’s choice. Hailing from Elizabeth, near Adelaide, he was another Gorbals boy, a mate of Jimmy Barnes. But George’s opinion was carrying less and less weight, given the way everything was going. (Ironically, Fryer would go on to sing alongside Mark Evans in Heaven, an ’80s heavy metal band managed by Michael Browning.)

Other names bandied about included Steve Marriott, the former Small Faces/Humble Pie frontman, who was even older than Bon (and a singer Bon had covered and greatly admired); former Heavy Metal Kid Gary Holton; ex-Back Street Crawler Terry Slesser; and another couple of Australians: Adrian Campbell, who’d previously sung for a band called Raw Glory, and Scottish-born John Swan, who—along with his half-brother, singer Jimmy Barnes—had joined Fraternity (on drums) after Bon left in 1974.

Holed up in the rehearsal studio, Malcolm and Angus conducted the cattle call under the scrutiny of Peter Mensch and Mutt Lange. Gary Holton might have seemed like a good fit but the team was wise to decide against him, since he too would die young, in 1985. They were wiser still to pick Brian Johnson. Johnson at the time was working in a garage back in his hometown of Newcastle upon Tyne, after abandoning the musical career he had dreamed of since the first time he saw local hero Eric Burdon in the early sixties. His band Geordie had enjoyed a couple of minor hits in the early ’70s, but by the latter half of the decade their run was over.

The story goes that an AC/DC fan in Chicago sent Peter Mensch a tape of a Geordie album, and Mensch was immediately interested. Geordie was an undistinguished sort of hard rock outfit, but Johnson possessed a pair of lungs of the capacity required by AC/DC. Malcolm and Angus knew who he was—Bon had told stories of seeing this guy sing one time when Fraternity supported Geordie in the UK. Johnson was located, he squeezed an audition into his “busy” schedule, he impressed with versions of “Whole Lotta Rosie” and “Nutbush City Limits,” and he got the gig. “He’s got the range,” declared Mutt Lange. Bon wasn’t five weeks in the ground and Johnson was already the new singer in AC/DC.

Meanwhile in Newcastle, New South Wales, just north of Sydney, AC/DC’s original singer Dave Evans sat by the phone, dressed head-to-toe in leather and studs, waiting for a call which would never come.

Bon was one of a kind and the band knew he could never truly be replaced. Angus would now be the sole front man, the star attraction. Any singer would have to fall in behind him and just bellow. Which is what Brian Johnson did, and still does.

The next best thing to a Scot is most likely a Geordie, and in terms of temperament Johnson was just the sort of character AC/DC were looking for—down to earth, self-deprecating, and with a salty sense of humor. And Johnson—like Bon—was older, and wise enough to know not to overstep the mark.

The announcement was made on April 8. The band claimed Bon would have wanted it that way, and they were right. To have come this far and not gone on would have been a betrayal of all Bon’s efforts. Bon wouldn’t have sat around feeling sorry for himself. The ultimate irony, of course, given the American label’s complaints about Bon, is that Johnson’s shrieking style is essentially as unintelligible as Bon’s! He may never have rivaled Bon’s songwriting ability, but—helped by superior technology—Brian Johnson has served AC/DC, and Bon’s memory, well.

The band spent the first two weeks of April rehearsing with Johnson and Lange in London, and then set sail for the Bahamas, where they were booked into Compass Point Studios in Nassau.

In the same way they’d claimed they didn’t want a Bon clone—and in Brian Johnson, didn’t get one—the band also claimed they weren’t interested in “grave-robbing” any of Bon’s last song ideas.

But given the way the famous Young/Scott/Young writing team worked, it’s hard to imagine that, at the very least, some of Bon’s ideas didn’t seep into Back in Black, if only indirectly. And if some of these ideas were used—which would not have been unreasonable, since Malcolm, especially, had provided Bon with more than a few lyric lines and themes over the years—at least Bon might have been awarded a credit—but he wasn’t.

Highway to Hell had succeeded because Mutt Lange made the band sound bigger and smoothed out some of its rough edges. Back in Black succeeded because it sounded even bigger still, and because within that huge, enveloping ambience, it could afford to restore some of the sharper edges (culling a lot of the backing vocals). Highway to Hell is a warmer-sounding, more well-rounded album than Back in Black, but the overarching sonic vista of Back in Black, the vastness of its dynamic crunch, makes it irresistible, and although the later album is uneven (several of its songs are relatively weak), the superior half of it is so overwhelming, it sweeps everything before it. It is no surprise that by 2006 it had sold over forty million copies world-wide.

But Back in Black is more than just dedicated to Bon’s memory, more than a fully fitting tribute to him; it’s like a haunted house, a voice from the grave: Bon not going gently into that good night. It is significant that the graph of AC/DC record sales traces a steady ascent up to Back in Black, and after hitting that peak, begins to decline. It’s hard not to ascribe that to Bon’s fading presence.

Bon’s death was “the defining moment for AC/DC,” David Christensen wrote in the online journal fakejazz in 2001. “It solidifies the band as the hard living thugs they’d always played themselves to be, but is the inevitable end of the lifestyle they led and championed in their music. It gives everything they had previously released a dark pall and a bitter edge. And it was the event from which they could never recover. Though they released another strong record—Back in Black—the AC/DC of 1974-79 was gone and in their place was something else entirely, as evidenced by the tonal shift of Back in Black.”

Back in Black’s opening track, “Hell’s Bells,” is one of the slowest dirges AC/DC have ever recorded. Slowing the tempo a bit generally was one of the keys to opening up the band’s sound, but this track, obviously enough, was a funeral march . . .

AC/DC had a tradition of making ten-track albums, five songs per side. Of the remaining four songs on Side One, only “Shoot to Thrill” and “Giving the Dog a Bone” barely measure up; “What Do You Do For Money Honey?” and “Let Me Put My Love Into You” are both pretty ordinary.

The real riches lie on Side Two. The double punch of its opening, first the title track (the Greatest Riff of All Time), followed by “You Shook Me All Night Long” (the ultimate frat-house party-starter and pole dancer favorite, the only pop record AC/DC have ever made), cements the album’s impact. The side continues strongly too, with “Have a Drink On Me,” “Shake a Leg” and “Rock’n’Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution.”

“Back in Black is a Bon Scott album,” concludes David Christensen. “Though he does not appear on it, his presence, or lack thereof, defines every aspect of it. Though some songs were as menacing (the astounding epic opener “Hell’s Bells”) or as furious (“Shake a Leg”) or as nasty (“You Shook Me All Night Long”) as earlier AC/DC songs, the album feels emotionally heavy and dark. The fun is gone. The jokes fall flat. It’s obviously intended as a tribute to Scott, and it is effective enough in that sense. But the wild abandon is now tempered by an ever present sense of doom.”

But it’s one thing to say that Back in Black is driven by Bon’s spirit, that he was its “ghostwriter”; it’s something else again to find concrete evidence of his input. Listening closely to it, it is possible to hear things that sound like they could be Bon’s work—but also other things that quite clearly aren’t.

“Some songs on Back in Black,” says Anna Baba, “I could have explained too well, with much confusion and tears. They who call themselves mates and declare they don’t do it, but have done it, with cool cheek—sneaky! ‘Shake a Leg,’ ‘Rock’n’Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution,’ ‘Have a Drink on Me’ and others, obviously his, no-one else’s.”

Bon’s mother Isa has also said that Bon had already written a lot of lyrics for the next album when she saw him over Christmas in 1979. The band was always working on new material in the tour bus, Malcolm and Angus constantly trading licks, Bon and the Youngs trading tags and hooklines. This is classic organic rock songwriting, and if Back in Black was born anywhere, it was born there. But more specifically, Bon was in and out of the rehearsal room in London in late January/early February, playing drums behind Malcolm and Angus, trying out vocal lines and honing lyric ideas.

Angus actually told Australian Rolling Stone in 1997, “We were in doubt about what to do [after Bon died] but we had songs that he had written and we wanted to finish them.”

Bon had already sat in on sessions for “Have a Drink On Me” (which had its final title even then) and “Back in Black” (which didn’t). It seems unlikely that he wrote his own epitaph (despite the online myth of a bootleg demo of the song on which Bon sings!), but certainly Angus as well as Anna Baba dates the very Stonesy “Have a Drink On Me” to the period prior to Bon’s death.

“Rock’n’Roll Ain’t Noise Pollution” is another song whose provenance is confused. The party line goes that it was built from the ground up in the Bahamas—the only track to have been created this way. But while this confirms the fact that the other nine were all developed in London, Anna Baba says that this song, too, had its origins in London. Bon was inspired to write the lyric, she says, after the caretaker at Ashley Court, Mr. Burke, asked Bon to turn down the loud music late at night. And it certainly sounds very Bon . . .

Anna Baba isn’t the only one who believes that an examination of Bon’s notebooks would end all this speculation. But although Ian Jeffery, one of the “two big men” who turned over Bon’s flat after he died, has admitted that he has a “folder of lyrics of 15 songs” written by Bon, these lost scrolls remain hidden from view. And the credit for every track on Back in Black reads uniformly “Young/Young/Johnson.”

As if to reconfirm the truism that death is a great career move, interest in AC/DC ran at an all-time high in anticipation of the release of Back in Black. The UK’s Music Week top 75 singles chart for July 9 contained no less than four AC/DC “oldies”—“Whole Lotta Rosie” (at 38), “High Voltage” (48), “Dirty Deeds” (54) and “Long Way to the Top” (55). When the album was released at the end of July, less than six months after Bon’s death, it became an instant world-wide smash.

In Britain, it went straight to number one. In the United States, although it only reached number four, it stayed in the Billboard top ten for over five months. In Australia, it went to number two, held out of the top spot only by the Police’s Zenyatta Mondatta. By the end of the year, it had already sold three million units internationally, earning the band 27 platinum and gold awards in 8 countries.

It was AC/DC’s crowning achievement, and irrevocably established the band as one of the biggest in the world. As a result, the back catalogue—the six albums Bon made with the AC/DC—has never been out of print, and continues to sell strongly to this day.

JOE FUREY: “Again, a lot of the animosity at the time of his death, people just wanted to convey to his parents just how successful he was. Wanting to say, Do you realize now, you are going to become rich. There were people that wanted to make sure that was passed on, didn’t get lost in the vaults.”

Alberts sent Chick and Isa to Singapore for a holiday after all the fuss had died down. They were delighted with that.

GRAEME SCOTT: “Our accountant told us it would probably last two years, but it’s still going. We can’t really say anything, because it’s between the Youngs and the Scotts, AC/DC and us.”

It’s unfortunate Bon didn’t get around to providing anything for Irene, as he so clearly wanted to do, when his estate by now must have accrued millions. Irene stood by Bon through his worst period, and as much as she sometimes must have thought, If only I hadn’t pushed that divorce through, it’s testimony to her strength of character that she hasn’t become embittered.

Irene was pregnant when Bon died, and she went on to have a second son. She lives happily to this day—or like anybody, as happy as you can be with all the troubles you can have. But happy at best. In 2005, she put her collection of Bon memorabilia up for auction at Leonard Joel’s in Melbourne, including the letters published in this book; one item, a leather shaving kit his mother had given him, attracted a bid of $12,540 from an Australian collector. The letters are on now display at a bar called the Cherry, in Melbourne.

Bon may even have legitimate heirs who’ve missed the boat too. Over the years there’s always been talk of children he may have sired. No paternity claims have been made, however, even though a thirty-something Melbourne man was revealed in 2005 to have a very convincing case, and face. This man, a sometime musician, has neither played on his father’s name nor preyed on the estate, opting to protect his privacy and make his own way in the world.

Silver Smith got busted in London not long after Bon died. It was a bad bust: she lost her passport, and had virtually nothing to fall back on, so she went down hard. Bon invested a lot emotionally in Silver, and though she eventually made good—got clean, had a child, and is now a contributing member of the community back in Adelaide—she was probably the wrong woman for him at the wrong time. The sort of domestic dream Bon harbored for them both could never have come true.

Mary and Vince would both have kids, too, but Vince would lose his wife Suzy and son Troy to AIDS. Graeme Scott went to Thailand to live, where he ran a bar.

AC/DC hit the road for the first time without Bon, with Brian Johnson in his stead, in August 1980, after testing the water with shows in Holland and Belgium. They toured America for two months, playing 64 dates into September. It was business as usual. The album was approaching platinum status in the US. In November, the band toured the UK, then went on to Europe.

On the first anniversary of Bon’s death in February 1981, just after they had toured Japan for the first time, AC/DC finally returned to tour Australia for the first time since Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap. It was only four years, but it seemed like a lifetime. It was a lifetime.

Bon’s death was deeply felt in Australia. BON LIVES! graffiti spread fast. Yet Brian Johnson already had a hundred AC/DC gigs under his belt.

With shows in the five major capitals, Jake Berry came out to do a recce on the venues. Now armed with the props (the Hell’s Bell) and pyrotechnics they’d once disdained (their lighting rig was bigger than Kiss’s, the advance publicity claimed), at the dawn of the decade AC/DC led the charge into’80s arena rock.

Despite the high ticket price, an extra show had to be added in Brisbane and also at Melbourne’s Myer Music Bowl. AC/DC was already one of the slickest big touring operations on the international circuit (certainly one of the loudest!), and this visit to Australia was a triumphant homecoming of sorts—but again, this success was tainted somehow.

The Melbourne shows were the last of what ended up as a 119-date world tour. The gig in Sydney, the Young family’s adopted home town, was the wrap party. After opening the Australian tour in Perth at the Entertainment Centre on February 13, at which gig Bon’s family were guests of honor, the band moved on to Adelaide to play Memorial Drive on February 17. On Thursday the 19th, a year to the day after Bon’s death, a typical late summer storm rolled in over Sydney. It probably wouldn’t do to read too much into all the thunder and lightning, but the next day, when the gig was scheduled to take place at the Showgrounds, the wet weather turned bitter, and the show had to be postponed.

The show was postponed again on the Saturday night, but when it finally happened on the Sunday night, it was hailed as “a triumphant return.” Angus gets itchy fingers if his routine is interrupted, and he doesn’t know how to give less than 130%. With the Angels and John Swan’s band, Swanee, supporting, a 30,000-strong crowd as generous of spirit as Bon himself took his replacement to their hearts.

But as warmly as Brian was received, as celebratory as the crowd and the band’s experience was, there was still something incomplete: the absence of the prodigal son was conspicuous. The echo of Bon Scott reverberated in every song, every note and beat the band played.

After the performance came another trophy night. Everybody was there: George and Harry, the entire Young clan, Ted Mulry, Ted Albert and all the Alberts people, Mark Evans, Peter Mensch, Ian Jeffrey, Sherbet, Angry Anderson, Pat Pickett, Lobby Loyde, support bands the Angels, Swanee, Rose Tattoo—everybody except Angus, who slipped away. AC/DC’s backstage set-up now included a hospitality area in the form of a complete mock-English pub. Brian liked an ale or ten, and so did Malcolm. The band was presented with 40 gold and platinum albums. For many of the people in attendance, the occasion was bittersweet, a homecoming without a king. It was a bit like the fake pub backstage; you hadn’t needed props like that when Bon Scott was around, because Bon was a walking, talking one-man party.

A sour note was struck when an unidentified woman in the crowd yelled out for the original members of the band, but AC/DC rewrite their past as it suits them. She might well also have called for Michael Browning; he was going about his business elsewhere in the city, discarded by AC/DC after he’d served his purpose. Mark Evans would eventually win an out-of-court settlement with Alberts over unpaid royalties. “Sometimes,” he says, “when I’m in the right mood, seeing Bon on TV looking straight at me can still freak me out.”

“All I can really say is that Bon is still around and watching,” Brian Johnson said. “I can’t tell you anymore because it’s all so personal, but at night in my hotel room I had proof that he was there in some form. I know that he approves of what the new line-up is trying to do. He didn’t want the band to split up or go into a long period of mourning. He wanted us to build on the spirit he left behind.”

The band had to race to Brisbane the next day for the first of two nights at Festival Hall. And it was here that things started to really unravel. A couple of cars got torched after the show. Remarkably, hillbilly dictator Joh Bjelke-Peterson’s stormtroopers were caught off guard. That wasn’t going to happen in Melbourne, where the police surrounded the Myer Music Bowl, intent on nipping any public drunkenness or petty vandalism in the bud. On the first night, they made 30 arrests as the crowd dispersed after the show.

There was a real sense of closure here, in more ways than one. As Tadhg Taylor put it in Top Fellas, his brilliant history of Melbourne’s sharpie cult, those two AC/DC gigs at the Myer Music Bowl were “one of the most significant moments in the great sharp epic—the grand finale, the last big night on the town. Sharpie ended that night.” Taylor quotes a survivor called “Chris,” who recalls that while the cult was then in its dying days, “Every sharp in Melbourne would have been there and they went berserk, smashed all the trains and trams, pulled the cops off their horses, a riot. By this stage I was into punk and so these kids with moccasins and Bon Scott RIP T-shirts weren’t sharpies, they were headbangers.”

On the second night, the band played as if cowed, but still that didn’t stop the cops from arresting another 30 kids—and this in the city that now names a street after AC/DC! For the band, there was a real sense of déjà vu about it, another storm in a teacup like the punk rock shock Dirty Deeds tour the last time, and they left Australia again with no particular wish to come back soon. Indeed, they wouldn’t return for another seven years.

You would be forgiven, then, for expecting that at this stage the band might take a break, if only to catch their breath, if not reflect on all that happened in the past year. But Malcolm and Angus kept on pushing harder and harder, and that’s how it all finally caught up with them.

After Australia, they never even really went off the road; they toured the US from March until June. Atlantic had finally relented and released the initially rejected Dirty Deeds in May. Five years old, it soared to number three, where it sat for four weeks. The entire back catalogue was peppering the charts at that point; by now, Dirty Deeds and Highway to Hell have each sold over three million copies in the US alone.

There was still one height AC/DC hadn’t yet scaled, though—the top of the American charts. But they wouldn’t have long to wait. In July 1981, the band went to Paris to start recording the follow-up to Back in Black with Mutt Lange. The sessions became fraught. The band was drying up. The album that resulted, For Those About to Rock, which was released even before the end of that year, was an almost empty vessel. As a consequence, it was the last album Lange cut with the band—even though it became the first AC/DC record to reach number one in the US. It didn’t stay there long—in fact, it was the first new AC/DC album that didn’t outsell its predecessor—but it got there. There wasn’t much now that AC/DC hadn’t accomplished.

But if it is indeed a long way to the top, it can be a quick slide down the other side. AC/DC’s characteristic insularity degenerated, as it could, into paranoia. For drummer Phil Rudd, it was never the same after Bon died, and after touring For Those About to Rock for most of 1982, he started to go off the rails again—but more seriously this time.

The band would bounce back before the decade was out, but the mid-’80s was a testing time, creatively the lowest point of AC/DC’s career. 1983’s Flick of the Switch patently lacked the quality songs the band seemed to turn out at will when Bon was alive. Much had changed, and the production credit—to Malcolm and Angus themselves—was merely the tip of the iceberg. The pair had carried out a purge of the entire band and its support structure. It’s a classic syndrome: the successful campaigner who fears his own troops. But Malcolm and Angus never trusted anyone anyway. After sacking Mutt Lange, who had so successfully (literally) engineered their breakthrough (and who would go on to even greater success, practically inventing ’80s hair metal via former AC/DC support act Def Leppard), they sacked practically everybody else: Phil Rudd, for starters; Peter Mensch, who had himself usurped Michael Browning; even de facto official photographer Robert Ellis. The replacement of Rudd by Englishman Simon Wright meant there wasn’t an Australian-born member left in the band.

The larger disaster of Fly on the Wall, the 1985 follow-up to Flick of the Switch, prompted Malcolm and Angus to rethink their dictatorship. When longtime AC/DC fan Stephen King invited the band to contribute to the soundtrack of the film Maximum Overdrive, Malcolm and Angus re-enlisted brother George and Harry Vanda and found a born-again energy. The resulting track, “Who Made Who,” was a turntable hit in 1986 and served notice that AC/DC were on the comeback trail.

With George and Harry back at the controls, 1988’s Blow Up Your Video completed their return. The single “Heatseeker” was the band’s first bona fide hit (albeit a minor one) since “You Shook Me All Night Long.” The album was further helped, ironically, by a set of videos which saw AC/DC finally catch up, for better or worse, with MTV.

The next album, 1990’s The Razor’s Edge—on which George started work only to be sacked once more and replaced by Canadian Bruce Fair-bairn—consolidated AC/DC’s comeback, yielding the semi-hit single/ad jingle “Thunderstruck.” (By now, Brian Johnson had dropped out of the songwriting, leaving it all to the Young/Young axis.)

AC/DC was now a rock’n’roll institution—a living piece of rock’n’roll history, like the Stones, Tina Turner, or Bruce Springsteen. Successive generations of kids keep coming to see them just so they can say they saw them (which is the basis on which the Stones function today, too). And, just like the Stones, for all their imitators nobody does AC/DC better than AC/DC.

Still, when the band more recently contemplated sacking Brian Johnson—for whatever reason—they ultimately thought better of it. Not even AC/DC, they may have feared, could survive losing its singer for the second time.

George and Harry have never again reproduced the sort of magic they managed with ease in the ’70s, and Alberts today lives largely on the back of AC/DC and its other former glories. The Midas touch with which George steered the company deserted him not long after AC/DC first left the nest. The Angels left the label to sign to Epic in America. Rose Tattoo became an increasingly erratic proposition, and acts like John Paul Young and the Ted Mulry Gang simply faded away.

Alberts eventually moved out of Kangaroo House, studios and all, into a new building on Sydney’s leafy north shore. It was the end of an era. George and Harry found themselves out of time—and out of touch—in the ’80s, producing little except their own Flash & the Pan material. Even the Choirboys had left the label before they produced their one classic hit, “Run to Paradise,” for Mushroom in 1988.

Ted Albert himself had just bought into a promising stage musical called Strictly Ballroom when he died in 1990. The film version of Strictly Ballroom became a phenomenal success, and propelled John Paul Young back into the charts with a remixed version of “Love Is in the Air” from the soundtrack—but with Ted’s death a cloud descended on what was left of Alberts.

In the 1990s, AC/DC’s work rate slowed dramatically, as befitting a band whose members were all at least in their forties by now. Malcolm had already had to take time off to dry out in the late eighties. The official line was that he was suffering from “nervous exhaustion”; nephew Steve Young replaced him on the Blow Up Your Video tour and few people seemed to notice. Malcolm bought a house back in Australia, a palace in boho Sydney harborside suburb Balmain. Soon enough Angus also bought a property “back home”; both brothers divided their time between Europe and Australia.

It would be five years before the band followed up The Razor’s Edge with the Rick Rubin-produced Ballbreaker in 1995, by which time a clean and sober Phil Rudd was back in the fold. “The best thing was the return of Phil,” Rubin told Rolling Stone. “To me, that made them AC/DC again. You can hear it in how he drags behind the beat. It’s the same rhythm that first drew me to them in junior high. That groove is timeless.”

It would be another five years again before 2000’s Stiff Upper Lip. Stiff Upper Lip was AC/DC’s seventeenth album, produced by none other than big brother George. The family ties are still strong, and some of the touch is still there.

Of course, AC/DC could never be the same after Bon died. Not since the first rush of hits off Back in Black have they produced much to equal their best earlier songs. But while the Young brothers’ suspicion that they were regarded less highly post-Bon fed their paranoia for a long time, with the continuing success they have had, Malcolm and Angus are today much more comfortable with who they are. Like a vintage bluesman, AC/DC deserve the respect and success they enjoy. The energy and commitment they display is the least the punters should expect from any rock’n’roll band. But AC/DC have always been distinguished by their sense of humor and lack of pretension, too, and these are qualities they still retain.

Bon was contemptuous of the critics who misunderstood AC/DC, but the band’s critical reputation improved over time as it became clear not only that they weren’t going to go away, but that what they’d started had influenced the course of rock’n’roll history. They’re now a touchstone, and Bon himself is recognized as one of the great lost figures of rock.

Calling AC/DC a heavy metal band in the seventies was as inaccurate as it is today. To start with, they’ve never looked like a heavy metal band. Forgetting AC/DC’s glam-rock origins, Malcolm once commented, “It’s disgusting to see men prancing around with make-up on and hairspray wafting around them.” But AC/DC were never anything more or less than a straight rock’n’roll band. The confusion arises today because of the enormous influence they’ve had. The headbangers loved AC/DC from the very first, because—like Led Zeppelin—they could be embraced as a heavy metal band, even if they transcended the genre. AC/DC were a rock’n’roll band that just happened to be heavy enough for metal—and, as it also turned out, funky enough for hip-hop!

“The other thing that separates AC/DC as a hard rock band is that you can dance to their music,” says Rick Rubin. “They didn’t play funk, but everything they played was funky. And that beat could really get a crowd going. I first saw them in 1979, before Bon Scott died, opening for Ted Nugent at Madison Square Garden. The crowd yanked all the chairs off the floor and piled them into a pyramid in front of the stage.”

Before grunge, there was thrash; before thrash, there was hardcore; and before hardcore, there was punk. Before punk, before metal, there was heavy rock, as it was called in the early ’70s. AC/DC never fitted the punk stereotype, but as soon as hardcore came along they were recognized as an influence. And by the time thrash emerged—and remember that Metallica, for example, were called a thrash band when they first appeared in the mid-eighties—AC/DC’s influence was pervasive. (And who managed Metallica? And, for that matter, Def Leppard? Peter Mensch . . .) When Henry Rollins guested with Australian trio the Hard-Ons on a 1991 single version of “Let there Be Rock,” it was but one of a stream of tributes that continues to this day. The 2004 Australian feature film Thunderstruck makes a pilgrimage to Bon’s grave, which has become such a tourist attraction that it’s now protected by the National Trust.

AC/DC was a band that made their own path, and it was Bon who gave them the character and spirit they’ve only ever been able to approximate since he died.

“I don’t think there would have been an AC/DC if it hadn’t been for Bon,” says Angus today. “You might have got me and Malcolm doing something, but it wouldn’t have been what it was. Bon molded the character and flavor of AC/DC. He was one of the dirtiest fuckers I know.”

For all his flesh and blood reality, Bon lent AC/DC a mystique that the band now sorely lacks. Angus still parades in the school uniform he should have grown out of years ago, a cartoon character who comes off stage and admits it’s a role he plays. The band has become two-dimensional. They’re no less pudgy-faced and red-eyed, no less obviously, honestly human—which is admirable when one of the great failings of so many rock bands is patent, show-business phoniness—but they seem to be set on autopilot. Angus should cut that blues album Atlantic was always pestering him to do.

Bon provided the spark—sweet inspiration!—that ignited the fire, that elevated Malcolm and Angus above mere guitarsmiths, churning out riff after riff in a rote fashion. Malcolm and Angus patched up the band as best they could, and carried on. What else could they do?