CHAPTER 1

HISTORY OF CABALES SERRADA ESCRIMA

Centuries old, the Filipino fighting arts have long been a staple of Filipino society. They have played integral and often history-changing roles in the defense of the Philippines and survival of the Filipino. There are several hundred styles of these fighting arts presently being preserved and taught throughout the Philippines. Although known by many names—often descriptive of the styles and names of their founders and enemies—Filipino martial arts can be classified into five general categories: 1) fighting arts of the Indigenous Filipinos, 2) fighting arts of the Muslim Filipinos, 3) classical fighting arts of the Christian Filipinos, 4) contemporary fighting arts of the Christian Filipinos, and 5) modern Filipino interpretations of martial arts brought into the Philippines from other countries.

The Classical Art of Escrima

It is the classical and contemporary fighting arts of the lowland Christian Filipinos—commonly known under the generic rubrics of escrima and arnis—that are the most widely practiced in the Philippines and around the world today. These systems were traditionally steeped in baston y daga, or the concurrent use of a twenty-six inch stick and a twelve-inch dagger. Over the years, the single stick has come to the fore in many of these systems as their primary weapon.

The popularity of the arts of arnis and escrima began to resurface on the island of Cebu during the 1920s, at which time a number of martial arts practitioners began to openly teach their arts. In 1920, the late Venancio “Anciong” Bacon, the founder of Balintawak arnis, opened the Labangon Fencing Club—the first “commercial” arnis club in Cebu. Following Bacon’s lead, Johnny Chiuten, Islao Romo, and the Cañete brothers began openly teaching their respective styles of stick-fighting. The Philippine Olympic Stadium also began to promote full-contact arnis tournaments in the 1920s.

Grandmaster Angel Cabales

The art of Cabales serrada escrima traces its lineage from Stockton, California to Sudlon, Cebu. It is a system whose core techniques and movements are reminiscent of the stick and dagger systems that originated in Cebu during the early part of the twentieth century. It is not surprising, then, that one can find undeniable similarities in the systems of Balintawak arnis, kalis Ilustrisimo, decuerdas escrima, and Cabales serrada escrima. And like its sister arts, the single stick eventually became the primary weapon of the Cabales serrada system. It is important to note that although the serrada method of fighting is common in the Philippines, the art of Cabales serrada escrima per se did not historically exist there. It is a system that was developed by the late Grandmaster Angel Cabales in the United States in the 1960s, stemming from his background in Western boxing, decuerdas escrima, and his own personal innovations.

Dizon and Doce Pares

It was in the 1930s that the prominent escrimadors in Cebu and neighboring islands came together in the interest of perpetuating their indigenous fighting arts. To do this, in 1932 they organized the Doce Pares Association, which became the driving force behind the reemergence of Filipino martial arts and their integration into Filipino society. After the six Cañete brothers joined Doce Pares in 1939, political differences led a number of original members, such as Anciong Bacon, to separate themselves from the group. It was then that Eulogio Cañete became the new Association president—and the Cañetes have headed it ever since.

Angel Cabales often told stories of how his master, Felicisimo Dizon, was not only a member of Doce Pares, but was one of its most prominent fighters. He related how at a young age Dizon wanted to study under one of the greatest exponents of escrima, a hermit who lived in a secluded cave. In order to reach the hermit, Felicisimo had to courageously climb a steep mountain cliff. Upon reaching the top, he had to dive into a shark-infested lagoon, and then swim through an underground cavern to the hermit’s dwelling. This was done to prove his loyalty and dedication to the master.

Dizon was said to have learned the decuerdas style of escrima from this hermit. As Dizon’s abilities improved, he wanted to try out other renowned escrimadors. In those days, the phrase “try out” literally meant a fight to the death.

Dizon was said to have never turned down a challenge, and he would fight for nothing less than the death of one or both participants. As a result of his newfound reputation as a survivor of over a dozen “death matches,” Felicisimo Dizon was admitted into the Doce Pares Society, a brotherhood of the most renowned fighters of the area.

The final test of the Doce Pares Society was what some say came to be known as the “decuerdas tunnel” (so-named after Dizon’s fighting style). The tunnel was void of light, and its walls were fashioned with an array of hardwood sticks and sharp steel blades. The floor was rigged with crude foot levers that were triggered by pressure. As an escrimador advanced through the tunnel, he would inevitably step on one of the levers and release one of the weapons from the wall, which would strike out at him. Before he engaged in a test of skill and fate in the tunnels, an escrimador’s family would have a coffin prepared and waiting for him in the event that he was unsuccessful. Dizon, too, had his coffin prepared, as he honestly thought that he would not succeed in emerging from this tunnel alive. He did, and was said to be the only person ever to emerge from the tunnel unscathed.

To say the least, not only were many of Cabales’ students surprised to hear such a fantastic story, but so, too, were the members of the Doce Pares Association, who claimed the story was false. The suspect nature of Cabales’ claims concerning Dizon and Doce Pares stem from three basic facts: 1) the hermit’s cave and the so-called decuerdas tunnels have yet to be located in Cebu; 2) the style of Cabales and the Cañete’s appear to be diametrically opposed; and 3) the officers of the Doce Pares Association have kept detailed records of the various masters and students who came through their association, and Felicisimo Dizon’s name is nowhere to be found.

When I questioned Cabales further on this issue, he said that Dizon was not with the Cañate’s Doce Pares Association, but was a member of a much older Doce Pares Society that was formed somewhere in southern Luzon more than a century ago. When I questioned a number of senior Doce Pares Association members about the notion of there being an older society by the same name, they flat out rejected the idea and instead submitted that Dizon was only a minor master in Cebu, who used to sit and observe their practice, but would not join in.

It wasn’t until 1994—when I made my first research trip to the Philippines—that the stories of an older Doce Pares Society again surfaced. While in Manila I met and interviewed on several occasions the late Antonio Ilustrisimo and Jose Mena, both former friends of Dizon and Cabales. While Mena was unable to elaborate on the Doce Pares Society, Ilustrisimo had some interesting information. It appears that Ilustrisimo’s uncle, Agapito Ilustrisimo, became a spiritual leader on mystical Mt. Banahaw, located in Laguna province, southern Luzon, and that the original Doce Pares Society originated within the caverns of this holy mountain.

Independently of this, my ngo cho kun teacher, Alexander Co, gave me a locally published book by Vicente Marasigan—a teacher and writer of popular religiosity—titled, A Banahaw Guru: Symbolic Deeds of Agapito Illustrisimo (Ataneo de Manila, 1985). This book is a translation of an original religious document with the translator’s commentary. While the story of Illustrisimo’s “calling” to act as a spiritual leader begins in 1935, the book nonetheless provides some important and relevant information relating to Cabales’ story.

Grandmaster Antonio Ilustisimo

Grandmaster Jose Mena

In answer to the question of the viability of digging and living in mountain caves, many of which were made in southern Luzon, Marasigan translates as follows: “The next day, Ama said that they would first work on the cave at Tanag. They made a Templo in Tanag, and those digging were the people from Balibago, Luntel, Palingkaro, and Lian. Ama again departed but told them to continue digging… The next morning, they resumed the work of digging and boring the cave…” (page 156: 88a). And “Afterwards, they went to Balibago and built a cave there. And when they were digging, Ama said: ‘On the other side of that log, you will find two holes where you will take something.’ They continued digging and they found the two holes, and in them, a skull and a small knee-cap, and these were entrusted to the care of Mr. Poruso” (page 157: 89). And further, “The next day, they returned to widen the cave” (157: 90).

In support of the claim that Dizon could have swam through a lagoon to enter the hermit’s cave, it should be noted that Mt. Banahaw is located in Laguna, which was so-named because of its many large lagoons. Marasigan translates as follows: “The next cave to be dug was under the basement of the Central, and it was in that cave that the dignum wood was obtained for making canes and clubs used for exercise. These used to be made by old Costan and Candido. This cave was quite terrifying when those who worked there would come out, they would be bent and dizzy. At the bottom of the interior of this cave, there was water, said to be a sea, and witnesses testified that they could hear cockcrow inside” (158: 94a).

And in defense of a Doce Pares existing in Mt. Banahaw, Laguna, Marasigan translates as follows: “There was a meeting in the Templo; Ama summoned Octoman, Fortunado, Jesus, and Pedro. ‘Remember this, my sons, you represent the Doce Pares and the apostles, and you are responsible for this place: Kinabuhayan….” (185: 157f).

After interviewing Cabales, Ilustrisimo, and Mena, the heretofore fantastic story of Felicisimo Dizon, his hermit master, the cave and tunnel, and the Doce Pares Society started to come into focus. There were only two things that I felt were needed to validate this story beyond a doubt, and they were: 1) to travel to Laguna and try to locate either members of the Doce Pares Society or associates of Felicisimo Dizon and 2) to make a trek to Mt. Banahaw to see these caves and interview the religious dwellers there firsthand. And while I have yet to visit Mt. Banahaw, I did travel to Laguna in 1999.

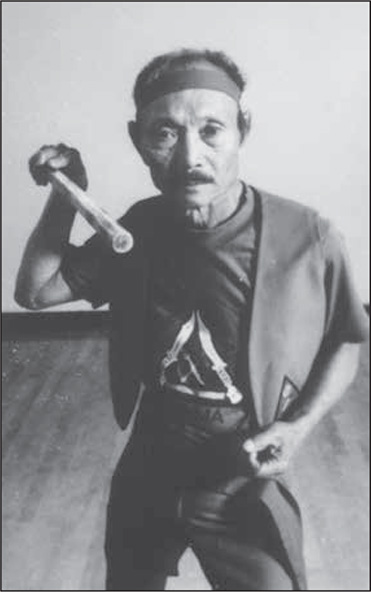

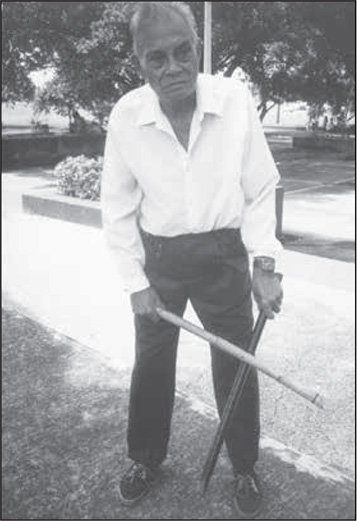

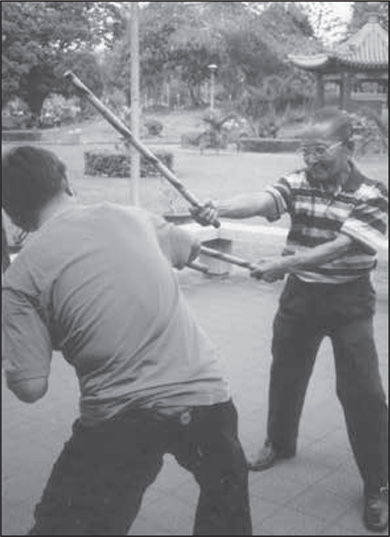

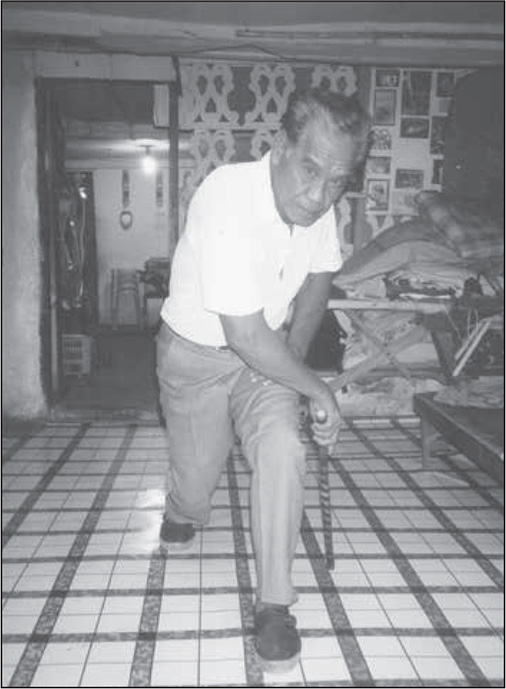

Grandmaster Madrigal

My trip to Laguna was organized by Abondio Baet, one of the area’s leading masters. It was through Baet that I was able to meet, interview, and “play” with six of the province’s leading masters: Modesto Madrigal, Reynaldo Baldemor, Rogelio Alberto, Gregorio Baet, Daniel Baet, and Abondio Baet. And while all of these men were familiar with the Doce Pares Society, it was Abondio Baet and Modesto Madrigal who were able to supply me with information on Felicisimo Dizon.

According to them, the Doce Pares Society was founded by a group of twelve escrimadors on Mt. Banahaw more than 200 years ago. Moreover, whereas the Doce Pares Association of Cebu translates their name as “twelve pairs” of hands or strikes, the Doce Pares Society of Laguna translates their name as a society of “twelve peers” of equally-skilled men.

Although a Cebuano, Dizon was eventually permitted to join the Society because of his skills in escrima and possession of highly powerful oracion (prayers) and anting-anting (amulets). According to Madrigal and Baet, an escrimador’s spiritual powers was the true test of admittance into the Society. In proving their skills, some escrimadors would swing a bolo from their hand at a bamboo tree ten feet away, and be able to cut through it from a distance, or cut loose the fruit from its branches.

In proving his oracion and anting-anting, Dizon emerged unscathed from the “decuerdas tunnel,” known in Laguna as kuweba ng kamatayan, or “cave of death.” The only other Society member whose name can be recalled during Dizon’s time is Julian Madrigal. Madrigal passed on the art to five students: Rofu Baguio, Felipe “Garimot” Baet (the father of Abondio Baet), Apolinar de Jesus, Pedro Magracia, and Modesto Madrigal. Modesto Madrigal, now 78 years old, is the last known disciple of the Doce Pares Society.

The Doce Pares Society disbanded in the 1930s, because many of the members lost interest and belief in the spiritual dimensions of the art. With the disbanding of the Society, Dizon headed for Manila, where he eventually became employed as a security guard on the Tondo shipping piers. It was while working the piers that Dizon befriended a young man named Antonio Ilustrisimo.

According to Antonio Diego (the heir of kalis Ilustrisimo) Dizon used to train together with Ilustrisimo and Antonio Mercado in San Nicholas, an area near the waterfront. The fighting arts of these men are similar because not only do they all hail from Cebu, but the men became training partners in Manila.

While many assume that Dizon, Ilustrisimo, and Cabales were contemporaries, they were not. In fact, Dizon was said to have been around 20 years older than Ilustrisimo, who himself was 13 years older than Cabales. So while they may have eventually been part of the same group, Dizon was the elder and more experienced, followed by Ilustrisimo, and then Cabales. In fact, Ilustrisimo told me of how he used to hold Dizon’s sword for him when awaiting his challenger’s arrival for a match. Another member of their training group was Floro Villabrille, the younger cousin of Ilustrisimo. Although both Cabales and Villabrille practiced with Dizon and Ilustrisimo, it was at different times, so they never met. As perspective, Villabrille was 4 years older than Cabales.

During the Second World War, Dizon, Ilustrisimo, and Pedic Naba joined up with the Filipino guerrillas to fight the invading Japanese forces. Toward the end of the war, Ilustrisimo tells of how the three of them were called on to round up the Filipino traitors, and execute them by cutting off their heads with barong (leaf-shaped swords).

Dizon, like Ilustrisimo and Cabales after him, eventually took work as a seaman, where he would not only take on challengers at other seaports, but also use his spiritual powers to heal the sick. According to Fred Lazo, a one-time student of Dizon, in his later life Dizon suffered a number of strokes that left him confined to a chair, and eventually he died of a heart attack in the early 1970s. Although he has passed on, the core of Dizon’s art has been spread around the world through the efforts of his student, Angel Cabales.

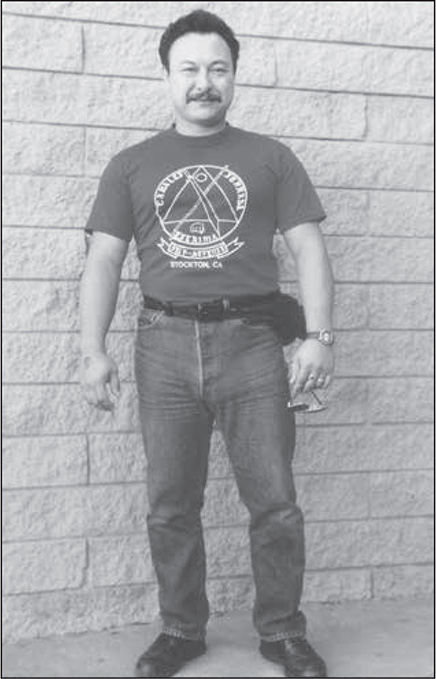

Angel Cabales

Angel Cabales was born on October 4, 1917, in Barrio Igania, Sibalom, Antique, on the island of Panay. Life for Angel began with a series of bad turns. Two weeks after his baptism, his mother, Marta Oniana, passed away. Upon hearing the news of his wife’s death, Melcher Cabales went crazy, sold his slaughterhouse, and moved to Mindoro Island, abandoning his three sons, Vincent, Canuto, and Angel.

Angel and his brothers were lucky because their aunt and uncle took them in and raised them as their own. Cabales’ aunt was a midwife and she took on the sole responsibility of raising Angel and his brothers after her husband’s subsequent sudden death. The four of them were fortunate, for they never lacked food or shelter. During the farming off-seasons, Cabales’ aunt would lend what extra money she had to local rice farmers, and in turn she would receive rice from them during harvest times.

Throughout his childhood Angel dreamed of becoming a professional boxer. One day in 1932, when Angel was fifteen, he witnessed some of the barrio’s young men fighting with sticks. Curiosity aroused, Cabales learned that they were in fact practicing the art of escrima, which was taught to them by a master named Felicisimo Dizon. After four months of pestering Dizon, Angel was finally accepted as his personal student. Realizing that he was more suited to stick-fighting than boxing, Cabales immersed himself fully in his newfound obsession: escrima.

At age seventeen, Cabales opted for the more exciting life of the big city. Going alone, he packed his bag and traveled to Manila. The first year was tough for him as he tried to survive by working various odd jobs. Cabales had no formal academic education; he claimed his wisdom came from the streets. Then in 1937, he gained decent work experience working as a foreman for the Madrigal Cement Factory in Rizal, a province near Manila. Cabales worked there for 1 year before returning to Manila, at which time he had little trouble finding work.

To his surprise, Cabales met up with Dizon again while working the Tondo shipping piers in Manila. It was here that Cabales also befriended Antonio Ilustrisimo, in addition to others, and they would all train together at night.

After a hard day’s work, the men would frequent the many local bars. In those days, girls, rice wine, and trouble came easy. It was then that Cabales fought in a number of challenge matches—some to the death. Through these experiences, Cabales, like Dizon, learned to appreciate the highly practical aspects of escrima.

Tired of violence and attracted by stories of wealth and prosperity overseas, in 1939 Cabales became a seaman aboard the cargo ship Don Jose. This vessel traveled to many ports around the world, including various places along the coastal United States.

As seafaring adventurers usually have it, these were not relaxing times. Long hours of labor with little money and food left an air of restlessness about the ship. Cabales and his friends often found themselves pitted against others they came across on their journeys. Many of Cabales’ friends were killed as a result. Aboard the ship, Cabales became involved in an altercation that led to the coining of his slogan: “Three strikes and a man will fall.” One day he was approached by a man claiming to be an escrimador and was asked if he would like to “practice.” He already knew what to expect because in those days, the word “practice,” like “try out,” meant a fight to the finish. Without hesitation, Cabales obliged this man, and with the third motion of his stick, the man fell and was never to get up.

Leaving a life of danger aboard the Don Jose, Cabales jumped ship off the coast of California. Upon coming ashore, he found a temporary home in a small Filipino community in San Francisco, where he made some extra money teaching a few private students the rudiments of escrima.

In 1945, no doubt in search of further adventure, Angel Cabales traveled north to Alaska and found work in the canneries and fisheries. After a short stay, as the result of yet another confrontation in which he severely injured three men, Cabales moved back to California. For the next 20 years, he worked as a foreman in the Stockton asparagus fields.

Life in Stockton was no less eventful. Once again Cabales built his reputation through escrima. After his arrival, he was asked by many to openly teach his art. Angel initially turned down these requests, feeling uneasy with the idea of teaching others how to counter the very skills that had kept him alive. He did, however, begin teaching a number of students privately in his many apartments during the mid-sixties. It was during this time that individuals like Dentoy Revillar were first exposed to his art.

In 1966, Max Sarmiento, Angel’s friend, student, and business partner, urged Cabales on, telling him that the future of escrima rested in his hands and that he should open a public academy. Actually, the idea for the academy was that it was to be a group effort. While Angel was to be the chief instructor, Leo Giron and Max Sarmiento would also teach their respective arts there, while Dentoy Revillar (a student of all three masters) would be available to instruct should one of the masters not be able to attend. Politics being what they are, the masters had a falling out, which led Cabales to open the academy on his own. And according to Dentoy Revillar, while many believe the academy was opened in 1966, it was actually March of 1967 that Angel Cabales opened the first public Filipino martial arts academy in the United States, thus earning him the title “Father of Escrima on the Mainland USA.”

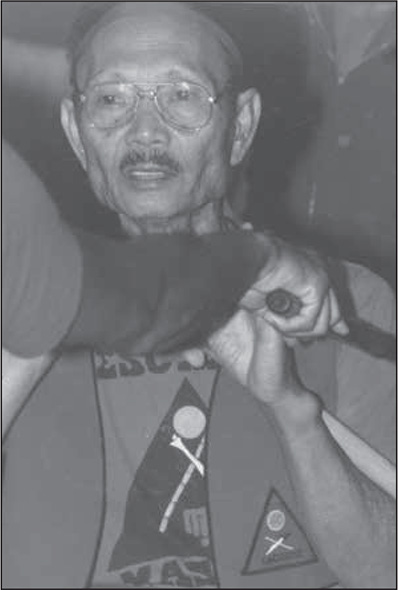

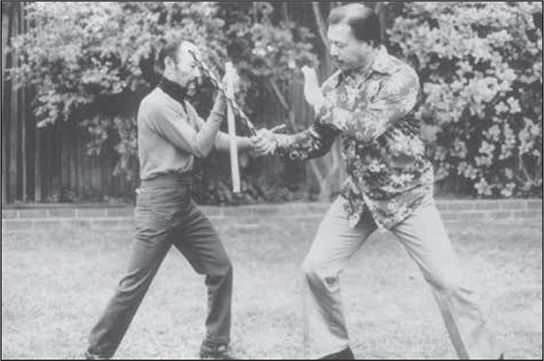

Angel Cabales instructs Max Sarmiento in escrima.

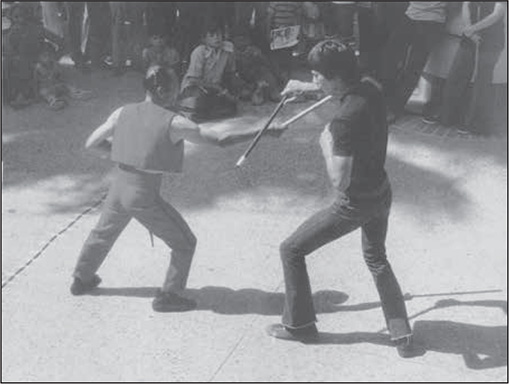

During the last 25 years of his life, Angel Cabales taught thousands of people versed in a multitude of martial styles. He gave annual demonstrations and exhibitions throughout California and much of the United States. During the 1970s, Cabales made two instructional films with his assistant Jimmy Tacosa for Koinonia Productions. He also made an appearance opposite Leo Fong in the movie Tiger’s Revenge, where he demonstrated the art of escrima.

Angel Cabales and Jimmy Tacosa give a demonstration.

During the last three years of his life, Cabales’ health began to desert him. With open-heart surgery behind him, he fought the odds, disregarded doctor’s orders, and continued to teach a packed schedule of private students and biweekly classes at his academy located next to Gong Lee’s restaurant on Harding Way in Stockton, California.

In September 1990, Angel Cabales was admitted to the hospital ravaged by walking pneumonia. What the doctors found, after a series of tests were run, was a cancerous tumor in his right lung. After 3 months of chemotherapy, which proved to be ineffective, cancer was also detected in his liver.

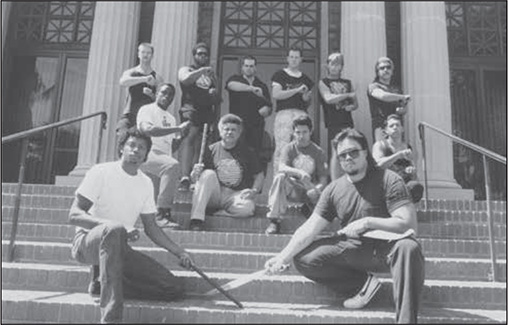

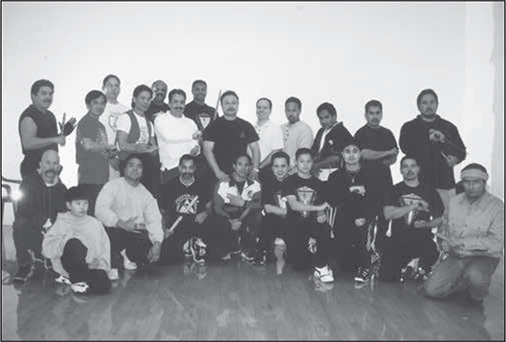

Serrada masters Jerry Preciado and Darren Tibon pose with their students.

Before he died, Grandmaster Cabales asked Darren Tibon and Jerry Preciado, two of his master graduates, to take over his academy. Feeling uneasy with the idea, since both had ties with Angel’s son Vincent, they declined and instead suggested that Angel leave it to his son. Cabales then turned his academy over to his son Vincent, who, although a master of the art, had been inactive for much of the previous decade. As his health deteriorated, more and more people began to come out of the woodwork looking for rank certification, especially a number of Angel’s former students, trying one last time to get what they were previously denied. It was to Cabales’ credit, however, that despite his need for financial stability and the need to feed his wife and two young children, he turned down bribes for certification.

Vincent Cabales

On March 3, 1991, at 11:15 A.M., Grandmaster Angel Cabales passed away. He left this world having led the life of a warrior: true to himself and his beliefs, and never afraid to take a stand.

Grandmaster Angel Cabales had certainly done more than his share of promoting and spreading the martial arts of the Philippines. In 1991, Angel Cabales was posthumously inducted into the Black Belt Hall of Fame as “Weapons Instructor of the Year.”

Angel Cabales’ tombstone.

During the quarter century that Angel Cabales had publicly taught his art of escrima, thousands of people had passed through the doors of his escrima academy. It is truly amazing, in a world of exploitation and self-proclamation, that Grandmaster Cabales had never lost sight of his ideals or compromised rank for political reasons. Forty-nine years after his arrival in the United States, Cabales had only awarded sixteen of his nearly seventy instructors the rank of Master. It is the quality of his master graduates that gives credibility to his system, not the quantity.

10 years after Cabales’ death, Masters, teachers, and students gathered to support the publication of this book.