CHAPTER 4

ART AND ANGEL

By Art Miraflor

My family moved to Stockton, California in 1968, when I was 16-years old. I was brought up in a very good Christian environment. As a teenager, I did not get into a lot of trouble—it’s probably that I just didn’t get caught. My dad, Job Bing Miraflor, asked me one day, “Do you want to learn a martial art?” I didn’t know what martial art meant; I thought it was a new dish or game.

After visiting six or seven schools I became a little disappointed. At the judo school, they were grabbing and throwing students all over the mat, which, being under 100 pounds, scared me. The tae kwon do school was doing some mean kicks that looked too hard for me. The karate school was really hitting hard, grabbing, and throwing. Also not my style.

Then one day, my dad was at his doctor’s office, Dr. Bernadino, who happened to be a Filipino. My dad asked him if he knew of any Filipino martial arts schools in town. He replied that the only one he knew of was open to the public. He gave my dad Grandmaster Angel Cabales’ address on Harding Way and El Dorado streets, next to Gong Lee’s Chinese restaurant (still good food by the way).

After being disappointed by the other schools, within 30 minutes I made up my mind this art was it. I told my dad I wanted to start right away, and said I thought I could whip everybody in the class. Of course he told me to zip it!

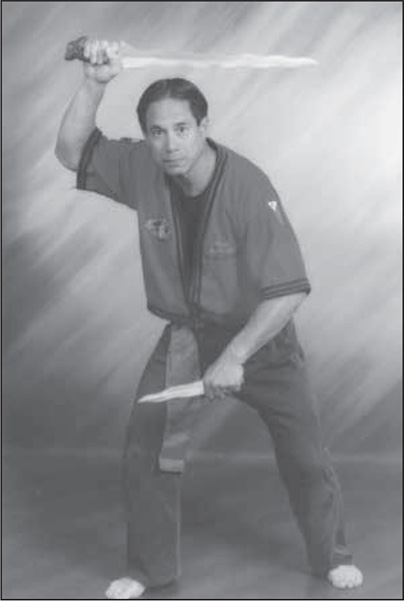

Art Miraflor

I came from a family of four girls and four boys, and we didn’t have a lot of money, so my dad decided to sign just me up. After several months, my dad started to pay for my younger brother Abel B. Miraflor, who at thirteen became my sparring partner.

When I first met Angel Cabales, he had this big smile that would squint his eyes, he had a strong grip, and he was short in stature. I said to myself, How bad is this dude? Only later did I find out how deadly he really was.

Angel told my dad it would be twenty dollars a month and that practice was held on Monday and Wednesday nights, from 7:00–9:00 P.M. I always made sure I was the first to get to class to help my master open the doors and carry in the bag of sticks.

When we talked to some of the other schools, they said only the black belts or advanced students could practice with sticks—I guess for control. What I liked about this class was that you started off the first night with a stick in your hand.

When I started in 1968, Angel did not have any paperwork—not an application, a clipboard, a flier, charts, not even certificates. So since everything was in his head, you had to be at every class consistently, listen very well, and attempt to understand what he was trying to say over his strong accent.

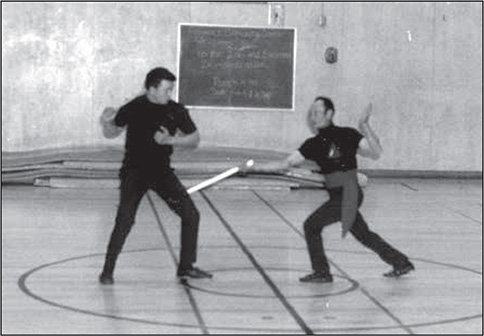

Angel Cabales strikes at Dentoy Revillar.

I don’t remember the names of all the students who were there when I started, but there were about five of us. I think his school had started only a year and a half earlier, so he was just getting the word around. Besides Grandmaster Angel, the next head instructor was Dentoy Revillar (whom I’ve always had respect for as one of the fastest escrimadors around), and the top student was Rene Latosa (this guy was fast and serious).

One of Angel’s students was Kathy Lee, the daughter of the owner of the building and restaurant next door. This girl was deadly; I’ve seen her hit so hard she knocked the stick out of Angel’s hand several times. She would come to visit wearing a minidress and high heels, always dressed up, and she would ask who wanted to practice. Most students started to hide because she was good, and they didn’t want to get hit. As of this writing, she is now the Head Clerk for the City of Stockton.

I enjoyed practicing in the old studio. It had a lot of room and that old rustic look, something like what you see in the movies, and the old wood floor was the best. Angel would spar or do “lock and block” with Dentoy, and his shoes would get clacking—it sounded like he was tap dancing.

The first night I started training I had to borrow a stick from Angel. One of the first things he taught me was how to hold the stick. We used a 24-inch stick for the most part. He told me to grab it with a firm grip about 1-inch from the end. He said when you grab a stick, or any weapon, you treat the side your knuckles are on as the blade of a sword. As you swing the stick, you are slicing through your opponent using your complete body torque.

Next he taught me how to stand, and that the defensive stance was a relaxed but ready stance with your stick down at your side ready to block. Your feet should be shoulder’s-width apart and you should be standing normally. He explained that you do not watch the stick, hand, or eyes, but use peripheral vision and watch the chest and neck area. The saying, “the hand is faster than the eye” is very true.

Another early thing I learned was how to twirl the stick. He then showed me some stick and hand exercises. He said now I was ready to deliver strike number one. After he taught me the first strike and I practiced it a dozen times, I was ready for the first block: the outside common. Since he was short and able to get in tight and low, Angel expected everybody else to do the same. I was about 5 foot 6 inches and around 97 pounds. He always stressed to stay low, ready, and balanced. At the end of each block, he would push my chest or shoulders to check if I was braced.

Angel made me do each block at least a dozen times each night we practiced. When I didn’t have anyone to practice with, I would practice in front of a mirror or tall chair. He showed me how to develop speed and control, by striking at an object with a swinging stick at full speed so you could hear the wind, and than stopping it one inch away from the object, until you could do this without hitting it with your eyes closed.

Angel’s classes at this time were not very strict. By that I mean that if you came in or left and forgot to salute, he didn’t make you drop and do twenty push-ups. However, we were taught to respect our master by saluting him as we first met and as we left. He also taught me the proper way to shake hands with anyone. He said that as you shake with your right hand, your left hand should grab the other person’s right wrist. This way the person would have less a chance of starting to shake your hand and then thrusting his right hand into your gut.

We started each class close to seven o’clock. We would stand in a straight line, or two if we had more students. Angel and Dentoy would stand in front facing us, and then we would salute. They told us who we would practice with and what number to teach or practice. We would practice for about an hour, take a 10- or 15-minute break, and then practice until nine or so.

One time, a student named Keith Scott was laughing a little too much while practicing. Dentoy was serious for the most part, and he went over to Keith and told him to punch at him. Being an obedient student Keith punched at Dentoy. Dentoy blocked and took Keith down to the floor. Keith got up and asked, “What was that for?” Dentoy said, “You swung at me so I had to defend myself, next time quit laughing and start practicing.”

As I practiced, I got faster and started to flow with balance and control. When I was there, Angel had his class structured so that it should have taken about 1 month to learn each strike and all the blocks for that strike. Now, to make it through all twelve strikes and blocks would take an average person about one and a half years to complete Angel’s system.

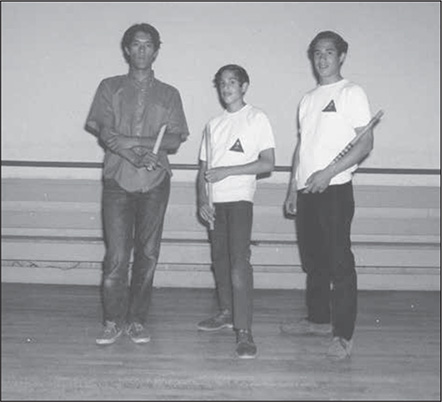

Rene Latosa, Abel B. Miraflor, Art Miraflor, circa 1968.

The Miraflor brothers flank Dentoy Revillar.

From when I started, it took me 10 months to complete all twelve strikes. Now, that was not normal. Angel did not move you to the next level or strike until you passed when he tested you, and he felt you were ready to move up. Up to that time I was paying twenty dollars a month. Then, Angel said he would make me an assistant instructor under Rene Latosa and only charge me ten dollars a month.

Mixed with our regular stick practice, we did some kicks, knife, hand-to-hand, and stick-to-hand. Our kicks were never higher than our waist, with several outside and inside blocks. We did knife defenses against one to five strikes, including takeaways (disarms). Our hand-to-hand was real interesting, because when you were able to move the stick with a blur and have 100-percent control, when you put the stick down, your hands were three times as fast. Even to date, I feel my right hand is fairly fast because of this training.

Now, when you practiced stick-to-hand, you were talking about the real thing. That’s when you had to really move and get with the program. I remember Angel always signaling me out to do “lock and block” or spar. On “lock and block,” he would deliver any of the twelve strikes, following in between each strike with a number five strike with a short 12-inch stick in the left hand, thrusting at your gut. You talk about a workout! That and sparring could give you a cardio, if you’re not in shape.

When I sparred, I got down to my knees, touching the ground, and drove you into the wall, going 100 miles an hour. Besides padded stick fighting, sparring stick to stick is the next thing to a real fight. You don’t know what number the other guy will deliver, and it comes from all angles.

I remember another drill Angel would do in class. It was like lock and block, but with one stick; I always called it fakes. He would position himself as if he was delivering a number two, but halfway through his strike, he’d change and hit you with a number four. Or he would start out with a number three and change to a one. This type of drill is what really made you fast, proud of your style, and self-confident.

I was with Angel from late 1968 to 1972, when I was drafted into the Marines and sent overseas. Most people don’t know this, but during this time, there were more masters and escrimadors teaching under the same roof at one time than at any other time in the history of escrima in the United States.

To the best of my recollection, there was Grandmaster Angel Cabales, Grandmaster Leo Grion, Master Gilbert Tenio, Master Dentoy Revillar, Master Max Sarmiento, and several other instructors that always came by to visit and see how the first public escrima school was doing, such as Art Diocson.

I remember Grandmaster Leo Giron coming in and showing us some of his de fondo style with a 30-inch stick. His wife would come with him and sit in the corner, on the left as you would come in the door to the class. She would sit and watch everybody, while crocheting and making gifts for other people. She was a very sweet person, and I miss her.

One of the most respected persons, and one whom I’ve always enjoyed, was Master Max Sarmiento. He just had a certain way about him that made you stop, listen, and ask questions. In my years at the class, I don’t remember one time seeing a stick in his hands. He was deadly with his hands. He would move so fast and gracefully. He was over 6 feet tall and probably just over 200 pounds—the biggest Filipino I ever met. Yet he had a big soft heart, and would do anything for you.

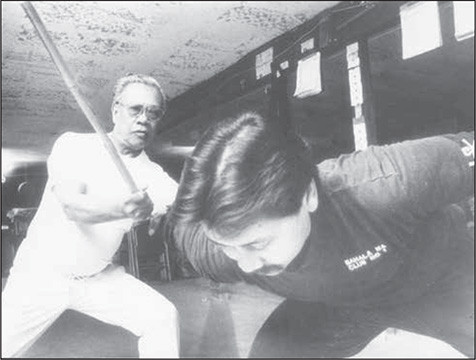

Grandmaster Leo Giron and Tony Somera.

For the most part Angel taught me at least 50 percent of the blocks himself, then I would say Rene Latosa taught me 30 percent, and Dentoy Revillar taught me the rest. My brother Abel and I would come to class every Monday and Wednesday and go home and practice almost every night. We loved what we were learning and wanted our dad to feel he was making a good investment. And he did.

Angel never taught us double stick, and the single stick was not over 24 inches long. The first hour of our class was normally dedicated to the stick, which was taught by Angel, and after break the last hour was for hand-to-hand, taught by Dentoy. We did not do any grappling, wrestling, or fancy kicks.

When sparring with sticks, we did not go looking for 18-inch short sticks; you used the same stick you always used. And when you sparred, you got as low as you could and used your arm, and swung using the full motion. By that I mean you were not allowed to just use your wrist, which is a lot faster, and that’s what most people do now.

My experience with Angel was my first contact with the martial arts world, so my allegiance is first to Grandmaster Angel Cabales over any other instructor. I will always uphold his concepts and beliefs. A lot of people want to claim him, and step forward and use his name since he’s passed on. But as martial artists, I think it is all our responsibility to carry on the arts and not speak negatively about someone who has passed on—or the same thing might happen to you.

This little essay I’ve given Mark Wiley describes my experience with Grandmaster Angel Cabales, and no one can change it or take it away.

May God bless all escrimadors in whatever good they do.