CHAPTER 10

ESSENTIAL ATTRIBUTES

This is the first chapter that deals with physical instruction. Without an understanding of the essential attributes (i.e., proper body positioning and mechanics, the concept of distance, methods of footwork, striking qualities, and use of the checking hand) one cannot effectively apply a technique in combat. There would be no foundation from which to build, no substance behind the blocks and strikes, and consequently no integrity behind the techniques.

Body Positions and Mechanics

According to Angel Cabales, there were traditionally thirty-three postures taught in the decuerdas escrima style of Felicisimo Dizon. These postures included, but were not limited to, methods of holding your weapon while walking down a crowded street, how to sit on your stick to allow for quick access if necessary, and how to stand with your stick in an unassuming manner with both of your hands free for use. These positions were essential for the survival of an escrimador in the Philippines at the time of their conception. However, since many of them are no longer practical or useful in our contemporary society, they have been forgotten or discarded. What has been retained, however, are the body positions and mechanics necessary to effectively employ this art for self-defense.

NATURAL POSTURE

The natural posture is just that: the natural posture we assume when standing in line or walking, with our shoulders down and hands by our sides. Since this is the most “natural” position one can assume, and perhaps the position one will find oneself in if attacked, all of the defensive techniques in Cabales serrada escrima are learned and practiced from this posture. In other words, practitioners of Cabales serrada escrima strive to perfect their techniques from a position of disadvantage, wherein they are not “squared-off” with their opponents or in a fighting stance prior to the initiation of an attack. It is believed that this posture offers practitioners the ability to develop the realistic reactions, reflexes, and timing necessary to defend themselves when unprepared.

THE ATTENTION POSITION

The so-called “attention position” is used only when receiving instructions during class time or in other formal settings. It is a position wherein the practitioner stands “at attention” with his or her feet a shoulder’s width apart, and the stick and arms intertwined, thus being non-offensive. This position has no relevant application in self-defense scenarios.

THE FIGHTING STANCE

This is the position that the practitioner assumes when “squared-off” with an opponent and preparing to spar or fight, and it is a variation of the strike two chamber position. To assume this stance, place one foot in front of the other, the distance of a natural step. The hand holding the stick is placed in front of the midsection with the stick in the crook of the elbow of the opposite arm, which is bent at the elbow with the hand placed over the navel (Figure 10-1).

THE LOCKED POSITION

The locked position is the final arm position assumed after the completion of a counter technique, wherein one is in a guarded, or “locked,” position that is said to be impenetrable. This position one finds is basically the transverse of the fighting stance, since the left hand is held above the stick, with hand and stick moving back and forth in small motions (Figure 10-2).

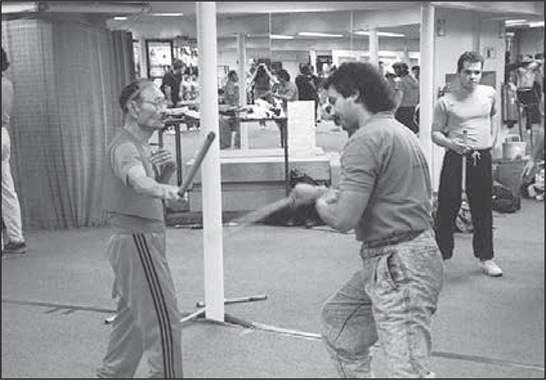

10-1 Cabales in the fighting stance.

10-2 Chuck Cadell in the locked position.

USING PROPER MECHANICS

The techniques of serrada escrima are applied with speed and precision and with as little wasted motion as possible. All of the movements are condensed and solid—that is, with arms and weapon held close to the body, so as to reduce the chances of the opponent being able to counter them.

Any strike that is done with the mere extension of the arm is weak and considerably less than one that makes use of the entire body as a single functioning unit. A strike that is initiated from just the arm is only as strong as that arm, but a strike that involves the entire body is as strong as the combined elements of that body.

The power of the strikes derives from foot, hip, and shoulder rotation and from stomping. If the hips move first and the body follows, there is considerably more power and force generated than if just the arms or wrists themselves are moved. Therefore, the entire body must move in the direction of each strike and step so as to ensure proper body alignment and mechanics for power and stability.

Controlling Distance

Aside from strong fundamentals, one of the most important things an escrimador must develop is the ability to control distance and movement—both his and his opponent’s. In terms of escrima, there are generally three defined critical distances, or combat ranges that all techniques are said to fall within. It is within these distances that certain techniques may be employed more effectively than others. It is also the ability to control these distances, or fighting ranges, that determines the victor of a bout.

A critical distance can be defined as any distance that has the ability to form a crisis, or threatening situation. In escrima this refers to any distance from which your opponent can strike you with edged, impact, or anatomical weapons. Offensive as well as defensive strategies must be understood, developed, and mastered in each of the three ranges in order for one to truly understand the art. Moreover, the concept of distancing, or combat ranges, must be understood because there is no set numerical distance between each range, or between opponents when in a particular range.

THE CONCEPT OF COMBAT RANGES

Combat ranges in escrima are divided into long, medium, and close, and are those distances between opponents that at once affect and determine the effectiveness of one technique over another. When developing an appreciation of combat ranges in general, it is essential to understand that they are not predetermined but relative. In other words, one cannot say for sure, for example, that “long range” is a distance of 4 feet from an opponent. Rather, the critical distance of each range is determined by the height of both opponents and length of their respective weapons.

Combat ranges, then, are not “set” but conceptual, and determined by such factors as the relative height of the opponents, the length of their arms, and the relationship of both typology and length of the weapons they employ. Moreover, and depending on these characteristics, it is improbable that you and your opponent will ever be in the same range at the same time. In other words, while you are in medium range, depending on the physical characteristics of your opponent and both of your weapons, your opponent might actually be in long or close range.

Let’s now look at each of the three general ranges more closely.

Long Range

Long range is generally determined as that distance between you and your opponent wherein you can effectively strike your opponent’s body with your weapon at full extension of your arm, but you are too far away to check his weapon or use your empty hand (if unarmed) to strike him. At this range, aside from evasion, the only options open to you for defense are deflecting the weapon with your weapon, deflecting the weapon (if a stick) with your empty hand, or employing a time-hit by directly striking your opponent’s attacking arm or hand with your weapon while stepping or leaning off its angle of attack.

Medium Range

Medium range is the farthest distance wherein you are able to strike your opponent’s body or head with the extension of your weapon. While maneuvering in this range, there is also the possibility that your opponent may also be at a critical distance wherein he can strike you with his weapon. It is as a result of this danger that the checking hand comes into play at this range. The majority of disarming techniques are also executed in this range, because it gives you the opportunity, with the proper use of footwork, to effectively take away an opponent’s weapon while being in a position in which the opponent cannot strike you with his free hand.

In spite of popular belief, Cabales serrada escrima is a medium-range fighting art. This is evidenced in the concurrent use of the stick and checking hand during counters, and the insistence of Cabales that the exponent of his art not be so close to the opponent during technique execution that he or she can be struck by the opponent’s secondary hand. Furthermore, the term serrada, as used here, refers to methods of “closing-in” or maintaining a “closed guard” while countering, and not necessarily “close range.” Moreover, while many contemporary practitioners of the art use a short, 18-inch stick, the original length of the stick was between 24 and 26 inches—the length utilized by most medium-range escrima styles. And again, the concept of combat range is conceptually relative; so just because one might be in close proximity to an opponent does not necessarily indicate one is in “close range.”

Close Range

Close range represents that distance wherein you can effectively strike your opponent with either the butt end of your stick or with either hand, in addition to locking or choking him. Cabales used to say that when in close range, one is a bit too close to effectively use one’s stick to strike one’s opponent. At that distance, he continued, one should drop one’s stick and continue the altercation hand to hand. The empty-hand blocking and locking techniques of Cabales serrada escrima, then, are best utilized in close range. If one attempts to employ many of the serrada empty-hand locks from medium range, the elements of leverage and balance are lost to the opponent, who can use them to counter or “reverse” the locks.

Methods of Footwork

The effective execution of offensive and defensive techniques is grounded in proper movement and placement of oneself relative to an opponent. The control of distance and maneuvering to the opponent’s blind or weak side are best accomplished through skillful footwork. In the Cabales serrada system, there are five such methods of maneuvering in relation to an opponent.

REPLACEMENT STEPPING

Replacement stepping is the core of the defensive footwork because it effects both body shifting and zoning in the same movement. With this footwork, you are effectively replacing your lead foot in an effort to change your position in relation to a strike, while not changing your relative distance from the opponent. It accommodates the philosophy that while defending against attacks to the left side of your body, it is better to have your right side forward, and while defending against attacks to the right side of your body, it is better to have your left side forward (Figure 10-3).

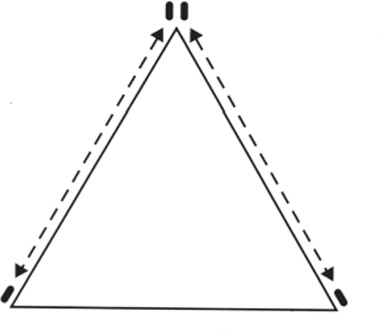

Although all replacement steps are based on the same theory of maneuvering along two sides of an isosceles triangle and replacing the lead foot at the apex, and although all employ the same general movements, there are several ways to perform the replacement steps, each depending on the type of attack and the practitioner’s last movement.

To perform the basic replacement step, begin in either the fighting or locked stance, with your right foot on the apex of the triangle and with your left foot at the left base corner. Move your left foot to the point of the triangle, next to your right foot, and as it meets your right foot, move your right foot to the right base corner of the triangle. You have now changed leads and shifted your body to face an attack from the right. Perform this sequence again on the opposite side, and then replace your steps as many times as necessary to effectively defend yourself and end the altercation.

10-3 Replacement Stepping Triangle

A secondary method of employing the replacement steps is performed by first sliding back the lead foot a quarter-step followed by a full step with your rear foot before replacing your steps and lead leg. This variation is generally initiated from the natural position and is used when more distance is needed to effectively block or avoid an oncoming strike, especially when you have yet to achieve a “good” distance between you and your opponent.