In the introduction I described a patriotic response to the events of 9/11 founded on a pre-existing ‘banal nationalism’. This response cultivated a sense of crisis, cast 9/11 in reductive Manichean terms and recalled US history in a partial way, especially through a jingoistic view of World War II. This avowedly patriotic response could be found in the mass media, in the speeches made by politicians and policymakers and across significant realms of popular culture, including the film industry, which used self-censorship and the reconfiguration of the release dates of a number of films to align itself with the prevailing cultural mood. In contrast to many books that address popular cultural responses to 9/11 – and which trace these responses into film culture – I wish to begin by examining films that, even in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, can be said to take an opposing view. In chapter two I examine a cycle of what I call ‘unity films’, but for the moment I wish to draw attention to those responses that resisted the easy constructions of national identity found in the mainstream media immediately after the attacks. This cycle of films indicates how processes of contestation and resistance were active from the very moment of the attacks, and how these processes would – over the long arc of the next ten years or so – remain available and be returned to.

In The Forever War, Dexter Filkins, a foreign correspondent for the New York Times, describes being at Ground Zero when the attacks took place:

Walking in, watching the flames shoot upward, the first thing I thought was that I was back in the Third World. My countrymen were going to think this was the worst thing that ever happened, the end of civilization. In the Third World, this sort of thing happened every day […] I don’t think I was the only person thinking this, who had a darker perspective. All those street vendors who worked near the World Trade Center […] When they heard the planes and watched the towers fall they must have thought the same as I did: that they’d come home. (2008: 44–5)

Here, Filkins distances himself from the predicted reaction – that the collapse of the Twin Towers would provoke a response of the kind already described in the introduction to this book – and instead identifies with a group of people with lived experience of the Third World for whom the violence would be in some way recognisable. Filkins’s ‘doubled’ response points to the way in which 9/11 propagated not only understandable reactions of fear, anger and the desire for retribution, but also something more complex: that is, reflection on the interconnectedness of the globalised economy, the already established and often unequal relation between the US and other nations and the ways in which the Third World is a part of the lived experience and social and cultural histories of a large number of Americans. Filkins’s response was not unique; journalist William Langewiesche described how the scene he witnessed could be readily related to those he had seen in failed states around the world (2003: 8–9). Similarly, E. Ann Kaplan, in the introduction to

Trauma Culture, describes walking through Manhattan shortly after the attacks and experiencing, in sharp contrast to the wider media discourse, ‘the multiple, spontaneous activities [such as the building of shrines, the adornment of war memorials with peace symbols, graffiti calling for reflection] from multiple perspectives, genders, races, and religions or nonreligions’ (2005: 14). Noam Chomsky, speaking on 21 September 2001, sought to amplify this kind of response as an alternative to the dominant discourse, noting that ‘even’ the

New York Times was reporting that ‘the drumbeat for war […] is barely audible on the streets of New York’, and that calls for peace ‘far outnumber demands for retribution’ (2011: 61). Another figure who adopted a critical and questioning stance was Susan Sontag (2001), who wrote a short polemical column in the

New Yorker, published on 24 September, that suggested that the attacks might have been a consequence of previous US actions, especially the ongoing bombing of Iraq after the first Gulf War. Sontag’s attempt to establish rational cause and context and to figure the event as the result of some form of interrelationship between the US, the perpetrators of the attack and the wider world was quickly censured, and she became the victim of vitriolic condemnation (see Faludi 2007: 28–30).

4 As later chapters of this book will demonstrate, these responses were prescient: it was precisely these themes that would give structure to much post-9/11 cinema, though the shift from the one response to the other would be fraught and take time. The prevailing cultural mood, however – seen clearly in George W. Bush’s Manichean construct, ‘Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists’ – ensured that any response to 9/11 that sought to resist the call for retribution and attempted to figure the attacks as, at least in part, the result of complex, dialectical relations between the US and the rest of the world was, in the wider public sphere at least, quickly subsumed by the dominant media discourse (see Bush 2001).

Faced with censure, those with critical views often loudly protested that they were adhering to principles central to US national identity in their willingness to talk truth to power and in their refusal to bow to the prevailing ideological viewpoint. Todd Gitlin identifies that this disrespect of authority, what he terms ‘egalitarian irreverence’, is a key characteristic of US national identity and, as we shall see, it was an attribute that was widely, and often vocally, upheld (1995: 43). Using a national Random Digital Dialing (RDD) telephone survey in late 2001, Darren Davis and Brian Silver discovered that ‘53 percent of Americans attributed responsibility to the US for the hatred that led to the attacks’ and that ‘even among political conservatives, 42 percent saw the US as at least somewhat responsible’ (2004). The telephone survey indicates how, even under considerable pressure to conform to the mainstream media discourse, many Americans reserved the right to have their own opinions. Critical acts took a more coherent shape as the days and weeks passed: teachers at educational institutions staged teach-ins, consciously emulating the political consciousness-raising strategies of the 1960s and 1970s (see Anon. 2001). As Jacqueline Brady notes,

At a time when dissenting voices and contesting ideas seemed to be absent from public discussion, we hoped these teach-ins would provide a forum for exploring the dense map of political, economic, historical, cultural, and personal coordinates connected to the terrorist attacks. (2004: 96)

A group formed by relatives of some of the victims of 9/11 called ‘September 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows’ stated that their mission was to ‘seek effective nonviolent responses to terrorism’ and ‘to spare additional innocent families the suffering that we have already experienced – as well as to break the endless cycle of violence and retaliation engendered by war’ (see Lawrence 2005: 46). An anti-war bumper sticker read simply: ‘Justice Not Vengeance’.

The popularity of the bestselling book Why Do People Hate America? (2002) suggests that many Americans sought to make the events of 9/11 intelligible by means other than the mainstream news discourse. The relationship figured by the book’s title is phrased in adversarial terms – emphasising how a discourse using the strict binary oppositions of ‘us’ and ‘them’ was operative in popular culture – but authors Ziauddin Sardar and Merryl Wyn Davies offer an alternative to this binary reasoning, constructing instead a series of logical answers to the question posed (2002: 195–203). The book asks readers to consider how countries in the Middle East and Europe might view the US in critical terms, and most importantly, why this might be the case. Sardar and Davies argue that in place of hatred people should seek to make ‘visible the nature, conditions and dimensions of the problem so that new debates, new constituencies of dissent that bridge the divide between America and the rest of the world, can be built’ (2004: xii). In doing so, they claim, a patriotic nationalism, which constructs US national identity in a partial and insular way, might be resisted. ZNet, CNN, Comedy Central’s The Daily Show and other middle-brow areas of popular culture also offered some limited space for discussion and debate, and within a year of the attacks a number of anthologies, including September 11 and the US War: Beyond the Curtain of Smoke (Burbach and Clarke 2002) and September 11, 2001: American Writers Respond (Heyen 2002) sought to understand the attacks via a series of alternative critical frameworks. It is in this context – one of critical questioning, egalitarian irreverence and the active refusal of the kind of dominant ideological response sketched in the introduction and profiled in more detail in the next chapter – that the first wave of film production that directly addresses the experience of 9/11 must be situated. The remainder of the present chapter examines a number of early 9/11 films as articulations of an unruly, democratic and questioning response that would consolidate and gain in confidence and coherence as the decade progressed.

One of the earliest documentary films to show the events of 9/11 was Etienne Suaret’s

WTC – The First 24 Hours.

5 Screened at the Sundance Film Festival in January 2002, Suaret’s documentary is described by Stephen Prince as ‘one of the essential films about 9/11’ (2009: 126). The film is distinctive in a number of ways. First, the opening sequences feature ‘locked off’ shots of the second plane strike and the collapse of the North Tower; these shots are denotative, objective, unflinching: seeming categorical statements of fact. The decision not to edit from one view of the event to another – and thereby establish some form of continuity – leaves the offscreen space resonant and encourages the viewer to search for a suitable framework other than that provided by the mainstream media. Second, the titles are followed by handheld shots taken by Suaret in the aftermath of the attacks (carefully selected parts of his footage also appear in

In Memoriam (2002), discussed in chapter two). These shots are tentative, uncertain, thoughtful and quiet. There is no commentary, only the ambient sound recorded with the image. At regular intervals – almost as if offering a pause for thought – the sound drops out. This has the effect of aestheticising the image for a moment before, as the sound returns, the evidential nature of the footage once again comes to the fore.

These carefully considered aesthetic decisions are striking in part as a result of their marked distinction from the ways that the event was being depicted in the mainstream media and the heavily editorialised documentaries described in the next chapter. There is something forensic about the film’s gaze and its eye for counter-monumental detail. Film of deserted shopping malls and fast food restaurants – the word ‘evidence’ painted on a wall – recall crime scene photographs. Ground Zero is here a place bereft, and in need of investigation. In stark contrast to Ground Zero Spirit, for example, the futility of the rescue operation is expressed through images of workers forming lines, their bodies tiny and their hard work ineffectual against the scale of the ruins. In its blend of handheld vérité footage, careful, quasi-structuralist presentation of iconic scenes and a self-reflexive use of sound, WTC seeks a materialist aesthetic with which to respond to 9/11, one that details what has happened but also seeks to question the act of representation, especially where this is too quick to attribute meaning to an event that demands further, detailed inquiry. In this, the film is a corollary to collections of photographs such as Aftermath (Meyerowitz 2006) and works of careful observational journalism such as American Ground (Langewiesche 2003) that similarly blend an iconoclastic eye for detail, a fascination with the quotidian and the posing of difficult questions.

Other responses, appearing within months of the attacks, sought to record the many voices and opinions in play. In the weeks following 9/11, San Francisco-based experimental filmmakers Jay Rosenblatt and Caveh Zahedi invited 150 independent filmmakers and artists to create a short film in response to the events and their aftermath. From the sixty works received, thirteen were selected to form the feature-length omnibus film

Underground Zero (2002), which was shown at film festivals in the US in early 2002. Gareth Evans claims that the film was intended to ‘offset the monotone of political propaganda with a plurality of opinions’ and that together the short films claim ‘a degree of street-level access and democracy for the moving image, they make central the communal and private in the face of governmental blustering and manipulative patriotism’ (2002: 5). Following this democratic principle, the documentary film

Seven Days in September, directed by Steve Rosenbaum, brings together film footage of 9/11 shot by 27 different filmmakers. Screened in New York and Los Angeles in September 2002, each individual film, or series of film fragments, is edited in parallel in the chronological sequence in which the events unfolded. The film shows that on the day of attacks responses were very similar – shock, sympathy, bewilderment, anger. However, from the morning of 12 September, with some time for reflection, a range of views begins to appear. Filming from Sunset Park in Brooklyn, and reflecting on the now significant gap in the New York skyline, filmmaker Alan Roth admits that, although he is sympathetic to the plight of the people who have been killed, he ‘never liked the World Trade Center’: ‘I always thought, from a political point of view, that these two buildings represented, you know, what I thought was evil about the economic system in terms of its relationship to poor people around the world.’

In plain words, Roth articulates something that emerges across all the films discussed in this chapter: namely, reflection on the ambiguous meaning of the World Trade Center as a symbol. As he cycles across the Brooklyn Bridge into lower Manhattan, Roth films a group of people praying for peace and inviting passers-by to join hands in a circle to sing ‘Amazing Grace’.

Later that evening, and drawn to the crowds gathering in Union Square, King Mopalo, a filmmaker from South Africa, films a candlelit vigil he claims is driven by a desire to find some respite from the constant repetition of images of destruction on the television news. Stephen Prince notes that Mopalo’s film shows

one man in the vigil [who] decries the US treatment of Muslims, Palestinians and Arabs around the world and says that Americans have to reflect on this in connection with the attacks. Sensing that war could easily follow in the wake of the attacks, and expressing a wish to forestall it, the crowd begins singing ‘Give Peace a Chance’. (2009: 142–3)

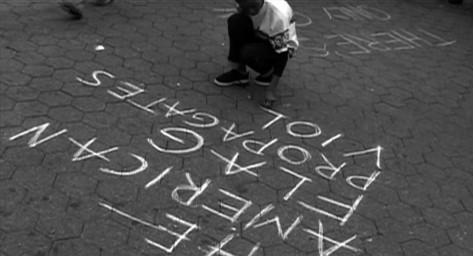

In another sequence filmed in Union Square on 13 September, chalk is given to people to write messages on the pavement. A black woman is shown writing ‘the American flag propagates violence’, leading a man to call for a dog to urinate on the message and a woman to attempt to wash the message away with a bottle of water. The crowd intervene and the documentary reports that an hour-long heated debate ensues, ranging across such topics as freedom of speech and the First Amendment, the necessity of war, the need to resist the call to war and God’s role in the attacks. This sequence ends with the plea, ‘Why don’t we stop arguing and start reflecting’, suggesting that there is also a desire to find some way of reconciling these opposing positions. Because of its inclusion of these difficult, often fraught, encounters,

Seven Days in September can serve as a marker of the critical and challenging views that were quickly excised from the popular media. David Holloway celebrates this response as ‘a decentralised republic of voices’: a complex, inclusive, democratic holler (2008: 102). The film corroborates Chomsky’s sense that the prevailing mood in New York was at odds with that of the mainstream media response and the complex reality on show foreshadows the wholesale questioning of the meaning of 9/11 that would shape popular culture through the following decade.

Fig. 1: Dissenting voices: Seven Days in September (2002)

The omnibus film

11′09″01 September 11, produced by Alain Brigand, brings together eleven directors from as many countries, each contributing a film lasting eleven minutes, nine seconds and one frame. The film was released in late 2002 in Europe, and early 2003 in the US, indicating that the filmmakers were writing, shooting and editing their work in the weeks and months immediately following 9/11. In keeping with this book’s focus on US cinema, I examine here the contribution to the film made by actor/filmmaker Sean Penn. In Penn’s film an elderly man (played by Ernest Borgnine) is shown living in a run-down but clean and orderly apartment in New York. The man has failed to get over the death of his wife and begins each day talking to her and choosing a dress for her to wear; the apartment is darkened by the shadow of the World Trade Center. On the windowsill a pot of roses has shrivelled and died, leading the man to observe that ‘like him’ the flowers ‘need light to wake up’. The use of split screen and slow motion draws attention to the film’s detailed

mise-en-scène: the rusted patina on a faucet, streamers blowing in the draught of an air-conditioning unit. The viewer is encouraged to scrutinise the detail of Borgnine’s craggy face, his stooped and scarred physique, and his vernacular, implicitly political speech – ‘rich people! A bunch of crumbs bound together by dough’; ‘they shouldn’t have been there in the first place’. Photographs on a bedside table show the man’s wife as a younger woman and a soldier in dress uniform. The soldier is possibly the man, or perhaps the couple’s son: in either case, the photograph indicates that this is a family that has served. Unusual shots from above provide an objective vantage point looking in on the man’s life. In this ‘plan view’ we see the apartment’s careful order: the man’s commitment to his chores, his carefully ironed clothes, his clean shoes. By these means the film skilfully conveys the life of an old man who has lived a tough existence replete with hard work and honest resolve, a man who is living in griefstricken limbo.

On the morning of 11 September, as the South Tower of the World Trade Center collapses, the shadow cast over the man’s apartment disappears and the room is filled with brilliant sunlight. Woken by the light, but unaware of what has happened, the man is confused – slow-motion and dropped-focus shots of his bewilderment are composited with fast-motion shots of the roses on the windowsill blooming. This dreamlike reality comes slowly into focus and the man excitedly tells his wife that she will now be able to grow plants. But then, almost immediately, he realises that his wife is dead. The man breaks down and cries and the camera tracks out of the apartment window, leaving him isolated in his grief as the North Tower collapses.

Fig. 2: Lives in context: Sean Penn’s contribution to 11′09″01 September 11

Penn’s simple and moving film – singled out for criticism by many reviewers – searches for a suitably complex response to the events of 9/11 in a number of ways: there is an acknowledgement that before the attacks all was not well (poverty and loneliness might well be the reward for a life of hard work and service; by way of contrast, high capitalism – symbolised by the Twin Towers – casts a long, unyielding shadow). As shown in later chapters, the signature colour of 9/11 is grey: both the colour of dust that subsumed lower Manhattan and a metaphorical colour – neither black nor white – that shades narratives of moral compromise. The shadowy greyness of the man’s apartment – and the short film’s fixation on the play of light and dark – puts Penn in the position of being a pioneer of this new colour array (subsequently picked up by a host of cinematographers across a range of post-9/11 films). For him the shadow, or greyness, is something that lifts on 9/11: the bright blue sky does not disappear in a grey dust cloud that immerses, engulfs, terrifies and disorientates. Instead, for the man, the collapse of the World Trade Center is illuminating. The attacks shed light on the man’s imaginary half-lit fantasy world, forcing him into a difficult and painful process of remembering which requires the acknowledgement of his wife’s death. Only via this painful process of truth being revealed and confronted in the moment of the Twin Towers’ collapse might positive consequences flow (i.e. the man is now in a position to move on). The aspect of the film that reviewers seemed to object to – the overly simple sense that Penn wishes to say that 9/11 is not an ill wind for all – must be judged against these other aspects: for Penn, the consequences of the attacks are manifold and complex, and, crucially, differentiated and calibrated in relation to different social perspectives and positions.

On the one hand, then, the film situates 9/11 within an intensely personal – one might say myopic – realm. On the other, this is not the usual strategy of eschewing the political via a retreat into the personal that gives shape to the films discussed in chapters three, four and six. Here, the personal is a realm shaped, indeed determined, by the political: 9/11 is cataclysmic, refiguring personal relations in ways not fully knowable. The film ends with the man in abject despair, but it is not the hopeless, terrified and fearful state presented as the default reaction to 9/11 by the mainstream media. It is a state that admits possibility for reflection and for change. Penn’s film offers a route out and away from the news footage of the attacks (which play in a very contained way on the man’s aged television set, undifferentiated from old reruns of Jerry Springer) into the various fraught viewpoints in evidence on the streets of New York immediately after the attacks, and from there into the world at large. It is worth mentioning, in anticipation of further discussion later in this chapter, that Penn’s film presents in cinematic form some of the controversies of the World Trade Center site – that the buildings were disliked by many Americans and were considered by many to be symbolic of the inequities of US capitalism.

Stef Craps argues that a key strength of 11′09″01 September 11 is the way it ‘decentres’ the events of 9/11 by bringing together a range of views from around the world, a decentring further indicated by the title’s use of the date as it appears on a European calendar (2007: 195). As such, the film might be said to belong to the kind of response embodied by the reactions of Filkins, Kaplan and the diverse New Yorkers recorded in active, often heated, debate at the various memorial sites in Seven Days in September. Craps notes that the contribution by British director Ken Loach, for example, links ‘11 September 2001 with 11 September 1973, when Chilean president Salvador Allende was killed during a CIA-backed coup d’état that put dictator Augusto Pinochet in power’, and that ‘in the episode contributed by Egyptian director Youssef Chahine, the ghost of a US Marine is lectured on various international atrocities carried out in the name of American foreign policy’ (ibid.). By these means the film contextualises the terrorist attacks within a broader geographical and historical landscape, insisting, as Holloway notes, that ‘9/11 and the war on terror would only become knowable events if knowledge about them was de-Americanised, or at least stripped of its American-centrism’ (2008: 159). Predictably, the film’s spirit of searching inquiry and desire to seek a broader set of reference points led to its denunciation by Variety as ‘stridently anti-American’ (Godard 2002), a fate that would befall myriad attempts to think beyond the dominant discourse in the months immediately following 9/11.

The first scene of Nina Davenport’s personal documentary film

Parallel Lines takes place at a lawn bowling club in San Diego, the affluent setting emphasised by the bright Californian sunshine. Here, Davenport asks an elderly Hispanic woman to reflect on the events of 9/11 and ‘how these events have changed the way you see the world’; the woman struggles to contain her tears and speaking in Spanish laments the lack of love in the world. Davenport, a New Yorker, then explains that on 9/11 she was located in San Diego for work and that she grew frustrated watching the events from afar on television. In mid-November, desperate to return home but also seeking to understand what had happened, Davenport placed her camera and sound recording equipment in her car and embarked on a six-week road trip back to New York.

Parallel Lines is a documentary film of her journey, and brings together digital video footage of the many conversations about 9/11 she had with the wide variety of people she met on the way with her recordings of her own thoughts and feelings in the form of a video diary.

As with the filmmakers who contributed to

Seven Days in September, there is something genuinely brave about Davenport’s commitment to seek out and interview a wide range of people at a time when trust among strangers was at the mercy of a prevailing culture of fear and paranoia. Her interviewees include, among others, a long-distance lorry driver (who did not hear of the attacks until 15 September because he was on the road), a conspiracy theorist (who claims he heard about the attacks five years before they happened), a pastor at a drive-through wedding chapel in Las Vegas, a park ranger, a mixed-race couple, a World War II veteran and beekeeper, a retired cowboy, a waitress, a black homeless man, a pair of teenagers, an ex-Marine and a group of cattle farmers. There are marked displays of patriotism: Davenport interviews a man who has put up a God Bless America sign on the road outside his diner and she joins marksmen shooting at images of Osama bin Laden at a shooting range. There are also accusations of government conspiracy and claims that 9/11 is a consequence of the US’s past misdeeds: two waiters from Waco, Texas, describe the US as the ‘land of the opportunist’ and ask ‘How can a country that has raped the Indians, the blacks, the Chinese, expect anything different than 9/11?’ A teenager in Natchez, Mississippi, states that he hopes that Bin Laden is captured alive ‘just to see how he thinks and how he views things, as opposed to how I see and view things’. Interestingly, as with

Seven Days in September, and with only one exception, religion appears as a force for good, with religious faith providing a moral viewpoint that inclines people to resist the prevailing jingoistic nationalist response. What emerges across many of the testimonies is an intensely personal response whereby 9/11 is measured in relation to pressing everyday problems and losses. A woman working at a petrol station in Ludlow, California, is brought to tears as she talks about her grandparents who live in New York and who she hasn’t seen in many years. In Pine Springs, Texas, an American man and Costa Rican woman who have a baby discuss the difficulty of their relationship: the woman is homesick and cries when asked about 9/11 – she states that when she saw other families suffering it made her feel pain to be away from her own.

As with Sean Penn’s film, 9/11 is here keyed into a complex web of personal experiences and relations, leading to reflection on the loss of family members to illness or personal difficulties, often within a context where poverty or the complexities of, say, immigration law have exacerbated difficult personal circumstances. As such, 9/11 meshes with a complex depiction of a US capable of treating 9/11 with disinterest, narcissism, empathy and generosity. It is through this collage of responses – some patriotic, some critical, some divisive and racist, many preposterous – that Davenport’s film becomes distinctive; 9/11 loses its sacrosanct status and becomes part of a complex reality. The US flags that feature so heavily in the film’s mise-en-scène mark the ways in which people reached for the flag in the aftermath of 9/11 but also the ways in which the flag takes on different connotations in relation to this range of perspectives. In an interview published on the BBC4 Storyville website Davenport stated:

A lot of the stories I heard were quite sad. I’m still not sure if it was because I was sad or because everyone was sad about 9/11 or whether that sadness was pre-existing. I tend to think it’s a combination – that 9/11 gave people a way to release their own private sadness onto this more national tragedy.

Davenport’s presence in the film, and her video diaries, offer the viewer a distinctly left-liberal perspective; we listen to her reflections on the different testimonies she has gathered and also to her commentary at the end of each day’s drive as she watches the television news and its description of the ongoing ‘war on terror’. In these scenes, there is an imbrication of a mainstream news discourse, the views of the characters that Davenport meets, and Davenport’s own thoughts, across which two discourses interact: one, a hegemonic mainstream response; the other, Davenport’s doubts and questioning of this mainstream view in dialogue with the gathering of a wide range of alternate views. Here the film is something of a model of post-9/11 cinema more generally, and the film’s title, which is said to refer not just to the Twin Towers and the dividing lines of the Interstate, but also to the individual storylines paralleling the nation’s tragedy, has, for this reason, provided the title for this book, which, like her film, seeks to examine these different versions of US national identity as they respond to the shock of 9/11.

There is a further dimension to the film. Davenport’s itinerary combines the serendipity of a series of chance encounters by the side of the road with the seemingly magnetic pull of sites richly imbricated in the US national imaginary. In her attempt to make sense of 9/11 she is drawn to, and intuits connections with, past events and the places in which they occurred. Her first stop is Las Vegas, Nevada, where she stays in a hotel that is a simulacrum of New York City: here there is a sense of unreality: of a doubling of, but separation from, the mediated event. From here she drives via the Grand Canyon to Monument Valley, Utah, the landscape redolent of John Ford’s many westerns. Here, Davenport talks to a Navajo Native American who describes how as a child he was prevented from using his native language. The man implies that violent events like 9/11 have precedents in US history and will continue to occur. In Los Alamos, New Mexico, in a museum commemorating the first nuclear bomb tests and the dropping of the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Davenport meets an elderly couple who had been involved in the project; they reflect that the test explosion was more spectacular than 9/11 and that the bombing was necessary to save US soldiers’ lives. Davenport’s liberal bent is in evidence here: as she leaves Los Alamos she listens to an audio book and explains that some historians claim that the bombs need not have been dropped. She here prefigures later commentary on the way in which the use of the phrase ‘Ground Zero’ recalls these earlier events of World War II (a point discussed further in chapter four). In Marfa, Texas, which she visits on 7 December (the sixtieth anniversary of Pearl Harbor, as already noted a key reference point in relation to 9/11), Davenport meets a beekeeper and World War II veteran, a member of the ‘greatest generation’ who warns that ‘you don’t want to look back too much do you?’ Indeed, in contrast to the way in which World War II was called upon by the mainstream media to celebrate US patriotism and consolidate the call to arms, the veterans of World War II, Korea and Vietnam who appear in Davenport’s film are shown to have been deeply troubled by their experience of war and counsel against it. Davenport states, ‘I wish I could feel wholeheartedly patriotic but instead I feel angry about all there is to be ashamed of in our history’. The symbolic locations she visits point to the way her journey might be understood as something of an unravelling or demythologising of the narrative of Manifest Destiny: an anti-road trip that seeks to encourage critical reflection on the ‘grand narratives’ that hold national identity in place.

Davenport’s journey also includes sites related to more recent events. She stops at the memorial to the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, a reminder that, in contrast to many accounts in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, terrorism had taken place on US soil in the recent past. In Somerset, Pennsylvania, Davenport visits the crash site of the fourth hijacked plane, and she spends time at the Pentagon in Washington, DC. At these sites she observes the informal work of commemoration as people quietly gather to reflect. The film ends on New Year’s Day 2002 with Davenport visiting Ground Zero. She does not film the site directly, preferring to show people as they leave the viewing platform. She interviews a photographer who is eloquent about not looking at Ground Zero directly – ‘you can’t look at the sun directly; you can only look at it through something that is reflective’ – and

Parallel Lines closes with a poetic shot of Davenport’s own shadow on the street in deference to the ways in which the voices that she has recorded and the places she has visited on her journey might speak more eloquently about the meaning of 9/11 than any image of the remains of the Twin Towers. This tactful and complex final image stands in marked contrast to photographs such as

Ground Zero Spirit and the wider official discourse.

Parallel Lines took some time to secure the necessary funding for release, only appearing in film festivals in the US in June and July 2004. However, it has been included in the first chapter of this book because Davenport’s journey and the voices of the people she interviewed were part of the immediate response to 9/11. Like Underground Zero and Seven Days in September, the film screened only at a number of minor film festivals, in independent cinemas and on television outside the US, with this slow and marginal release evidencing the way in which alternative voices and critical perspectives were, initially at least, curtailed.

The films described thus far run against the grain of the dominant nationalist response – that is, a patriotic clamour, the call to arms, the tightening of national security, and so on – and instead visualise a range of different responses, including the placing of the events of 9/11 into the context of the lived experience of an array of different Americans

and a wider historical perspective in relation to both US history and the history of relations between the US and the rest of the world. The films also touch on the

possibility of change of a different nature, that is, change for the better. In addition, these films indicate how the short film format –

Parallel Lines might also be seen as a series of loosely connected vignettes – was found to be the most appropriate form for gathering, but not unifying, a range of responses to 9/11. Of course, these films – the work of independent and amateur video/film artists, a collection of amateur film reportage, a European-funded portmanteau film and a low-budget, single-handed documentary – are marginal. However, the critical views they seek to articulate did also appear fleetingly in the multiplex via Spike Lee’s

25th Hour (2002), albeit as a result of a series of contingent circumstances.

25th Hour tells the story of New York drug dealer Monty Brogan (Edward Norton) and his last day of freedom before submitting to a lengthy jail term. The film was not initially intended as a 9/11 project. In fact, Lee brokered the deal to film David Benioff’s turn-of-the-millennium novel (published in 2000) with Touchstone Pictures well before the attacks. Lee shot the film in 37 days during the early summer of 2001 on a modest budget of $15 million. After 9/11, and in contrast to the many film producers who had attended the Beverly Hills Summit (who were discussing how to digitally manipulate their prints to remove references to the attacks), Lee’s production team discussed how they might create a post-9/11 mood around the existing script, one that would encourage a critical rather than a belligerent response (see Felperin 2003: 15).

6 The creative freedom to make these changes stemmed from a combination of Touchstone’s hope that the film had the potential to win an Academy Award and a supportive A-list star (Norton was paid $9 million for

Red Dragon (2002) but agreed to work on

25th Hour for a nominal fee of $500,000).

25th Hour’s dramatic opening sequence was one of the elements added to help create this post-9/11 mood. The sequence begins with abstract patterns of blue light framed by a cityscape at night. Long-time Lee collaborator Terence Blanchard provides the score – a classical rendition of Irish and Arabic folk music that lends a powerful cry of pain and suffering to the images. As the sequence unfolds, the cityscape is shown to be New York and the light is seen to be emanating from Ground Zero, where an installation of 88 searchlights was placed between 11 March and 14 April 2002 to create two vertical columns of light in remembrance of the attacks. This ‘Tribute of Light’ was a tangible desire to replace the loss, to fill the gap and to turn a negative, traumatic experience into a redemptive, affirmative experience; and yet, the lights are also ephemeral and fleeting, signalling both a desire to move on and the difficulty of doing so. Gustavo Bonevardi, one of the designers of the Tribute, stated,

We set out to ‘repair’ and ‘rebuild’ the skyline – but not in a way that would attempt to undo or disguise the damage. Those buildings are gone now, and they will never be rebuilt. Instead we would create a link between ourselves and what was lost. In so doing, we believed, we could also repair, in part, our city’s identity and ourselves. (2002)

The final shot of the sequence shows lower Manhattan in long shot from the perspective of Brooklyn, the bridge providing a line of sight across and into the city. This latter shot is carefully chosen as it presents the viewer with a perspective found in a number of iconic photographs of the Twin Towers before and during 9/11, and of the skyline without the towers after the attacks. The film’s opening sequence – a musical score of mixed ethnic provenance, the foregrounding of a solemn and reflective act of commemoration and a view of New York that offers some critical distance – conveys anger and loss, but also functions as something like a call to understand. There is no montage sequence of missing person posters and heroic firefighters, no detailed description of communal grieving and therapeutic healing, and no Stars and Stripes. Instead the film’s opening credits seem to wish to prime the viewer to subject the characters and the events of its narrative, and their relation to 9/11, to critical scrutiny.

In keeping with this, the film’s cinematography depicts the city through the understated use of a dark, steely grey colour palette. The reviewer at the Economist observed that the ‘bleached colours suggest a city covered with ashes’ (Anon. 2003), while Ryan Gilbey noted that ‘Lee’s use of space expertly evokes the general air of a city bereft (2003: 58). This style of cinematography to depict post-9/11 New York had become something of a cliché by mid-decade – In the Cut (2003), Flightplan (2004), War of the Worlds (2005), The Interpreter (2005) and The Brave One (2007) all adopt a similar colour palette. But, alongside Penn’s contribution to 11′09″01 September 11 with its play of light and dark and Parallel Lines with its final shot of shadows on a darkened street, 25th Hour is a pioneer of this way of using film form to key a searching account of identity and difference in relation to 9/11 and its aftermath.

The film explores the question of personal responsibility, with each of the main characters – Monty Brogan, Jacob Elinsky (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and Frank Slaughtery (Barry Pepper) – wrestling with alienation, regret and guilt. At key moments of hiatus in the narrative, the three characters are privileged with a shot in a mirror in which they contemplate their ‘distorted or fractured reflection’ in the light of their desire to change themselves and their acknowledgement of the difficulty of achieving this change (Gilbey 2003: 58). The characters’ respective existential crises are in part driven by earlier life decisions and experiences, thus reinforcing the film’s commitment to a thematic and narrative design set on interrogating the relationship between past and present.

The key sequence here is the scene in which Monty stares at his reflection in the toilet of his father’s bar; the sequence is preceded by shots of photographs of eleven firefighters killed on 9/11, and to the right-hand side of the mirror a sticker shows the silhouette of the Twin Towers against the backdrop of a US flag. As Monty looks in the mirror, his reflection (an angry alter ego) subjects him to a misanthropic rant that attacks the homeless, Blacks, Jews, the NYPD, the Church, Jesus Christ, Chelsea homosexuals, Bensonhurst Italians, rich Upper East Side wives, Hasidic Jewish diamond traders, Russian mobsters, Korean grocers, Pakistani and Sikh taxi drivers, Wall Street brokers, Enron, Cheney and Bush, Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, his friends, his girlfriend, his father and Osama bin Laden.

7 Monty’s alter ego’s rage-fuelled invective – blaming others for anything and everything – is a tactic that enables him to avoid negotiating the unpalatable fact that he has ‘been living high on other people’s miseries’ (O’Neill 2004: 6). It can also be read as an articulation of the violent, Manichean discourse prevalent in the aftermath of 9/11, whereby all others are subject to criticism and complaint and no self-reflection is undertaken.

However, as Monty vents his spleen, cutaways show the people who are the victims of his tirade, New Yorkers who look directly at the camera. In the early part of the sequence these New Yorkers appear to function as embodiments of Monty’s alter ego’s invective, but as the sequence progresses these caricatures give way to more objective, almost documentary-style portraits and then, finally, to images of neighbourhoods that give a sense of the city as the sum of its many parts. The sequence asks the viewer to reconcile Monty’s alter ego’s perspective with the presence of actual New Yorkers, encouraging an undoing of his reductive stereotyping, in what amounts to a complex acknowledgement of difference. The sequence draws to a close with Monty telling his alter ego in no uncertain terms that he himself is to blame – ‘No, fuck you’, he mutters calmly – and resolving to take responsibility for his own actions. In a theme that runs throughout the film, with people in positions of authority (a mid-level drug dealer, a city financier and a high-school teacher) shown taking advantage of those in less powerful positions than themselves, Monty acknowledges that he has behaved unethically.

This moral awakening is punctuated with flashbacks that show key moments of Monty’s life, thereby creating a strong sense of before and after, of lost opportunities and of regret. As such,

25th Hour indexes the need, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, for self-reflection and the assumption of personal responsibility, especially with regard to how actions in the past lead to consequences in the present. Monty comes to recognise that his past behaviour has harmed others and that he must break the cycle by acknowledging this, atoning for his actions, and pledging to take a different course in the future. This structure – operating in the realm of the personal – lends itself to being read as something of an insistence that the events of 9/11 should also give cause for reflection about US history and can be read in relation to Chalmers Johnson’s (2002) concept of ‘blowback’: namely, that the violent clandestine actions of the CIA and other government agencies may precipitate unanticipated and unpredictable events. While the dominant tendency was to efface the past, with 9/11 detached from any historical perspective,

25th Hour, like Sean Penn’s film (which points to the history of the World Trade Center) and

Parallel Lines (which connects the events to the mistreatment of Native Americans, a qualified account of Pearl Harbor and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), tells a story of how past events cannot be effaced or repressed, and how these events will both shape and determine future courses of action.

Having constructed this difficult reality, the film offers two possible endings to consider. On the day Monty is due to go to prison, one ending has him and his father driving west together – a road trip running counter to the one undertaken by Davenport in Parallel Lines – and we see him starting a new modest life and, in time, raising a family. This is the conventional Hollywood ending that would give the film uplift, activating as it does a deep-seated mythology of Manifest Destiny. Yet easy closure of this sort would simply continue the eschewal of personal responsibility that the film has shown to be the root cause of a wider social and cultural malaise, and, by extension, a causal factor in the terrorist attacks themselves. Monty must serve his time, the film’s logic suggests, if he is ever to get back to those values and experiences that his criminal behaviour has led him to let drift. As such, the film ends with his father ignoring the road west and taking his son to prison, indicating how, if the US is to build a fair, egalitarian, socially democratic society, individual Americans must refuse the myths of self and nation proffered by the mainstream media in the period following 9/11, and instead take responsibility for themselves and their actions. Here the film’s score deploys the Bruce Springsteen track ‘The Fuse’, taken from his seminal post-9/11 album The Rising, leading Jeffrey Melnick to note that

the appearance of Springsteen’s song acts as a final reminder…that 9/11 is the explanation for the feelings of fragmentation and loss that anchor the movie. 9/11 is the 24th hour implied by the title: the 25th hour is what comes after, which Lee’s film tells us looks a lot like prison. (2009: 13)

Through the selection of this seemingly more pessimistic ending, Monty is required to acknowledge how his own actions impinge on those around him – strangers marked by racial and social difference – and to change his behaviour in order to maintain the well-being of these people. At the film’s close, the New Yorkers who were subject to racial slurs in Monty’s alter ego’s earlier rant reappear and wave to him as he leaves, the city’s dispossessed wishing him well. In their hailing of him – a young black boy writes his name on the window of a bus and waves goodbye – they point to a reciprocity and sense of community in marked contrast to a general anger and suspicion based on their racial difference.

Crucially, the film does not offer redemption for those, like Monty, whose actions are exploitative and violent: corrupt corporations (Enron, Worldcom), capitalists (stockbrokers, diamond traders), politicians (Bush, Cheney) and terrorists (Bin Laden). These people – and the historical forces they signify – are identified as related to and responsible for 9/11. Here 25th Hour is more determined to address in a complex, or dialectical, way something gestured towards in Penn’s film and articulated with blunt rhetorical force in Seven Days in September and Parallel Lines: namely, that the inequities and corruption at the heart of neoliberal capitalism had a role in precipitating the events of 9/11.

Adopting a similarly iconoclastic position, a number of left-liberal commentators sought to counter the mass media’s construction of Ground Zero – via photographs such as Ground Zero Spirit – as consecrated ground (see Grant 2005). Edwin G. Burrows describes the troubled history of Manhattan from the colonial era onwards (this long history a counter-narrative to that of Pearl Harbor) and concludes that ‘the city has always been deeply implicated in the world’, and that ‘this is not the first time its people have paid a heavy price as a result’ (2002: 32). Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin argue that ‘however anonymous they appeared, the Twin Towers were never benign, never just architecture’ (2002: xi), and that

from the 1920 bombing of the Morgan Bank to the displacement of the largely Arab community that once thrived on the Lower West Side, to the destruction of an intimate architectural texture by megascale constructions, this part of the city has been contested space. (Ibid.)

Marshall Berman respectfully acknowledges the human losses on 9/11 – from stockbrokers to cleaners – but argues that this does not change the fact that the World Trade Center was an expression of ‘an urbanism that disdained the city and its people’ (2002: 6). Gabriel Kolko refers to the World Trade Center simply as ‘Wall St’, with the Twin Towers no more than synonyms for the US financial system in its entirety (2002: 11). These attempts to ground the experience of 9/11 in the material facts of the destroyed building’s primary use were not part of the mainstream response. David Harvey observes that on 9/11 the BBC reported that the terrorists had attacked ‘the main symbols of global US financial and military power’ whereas the US media reported an attack on ‘America’, ‘freedom’, ‘American values’ and the ‘American way of life’ (2002: 57). Afterwards, as ‘New Yorkers, faced with unspeakable tragedy, for the most part rallied around ideals of community, togetherness, solidarity, and altruism as opposed to beggar-thy-neighbor individualism’ (2002: 61), the media (via a series of short obituaries in the New York Times)

celebrated the lives and special qualities of those that died, making it impossible to raise a critical voice as to what role the bond traders and others might have had in the creation and perpetuation of social inequality either locally or world-wide. (2002: 59)

It is precisely this kind of stance in the mainstream media that the films described in this chapter, and 25th Hour in particular, seek to challenge.

In another key sequence in

25th Hour (also added to the film after 9/11 and shot on location at Ground Zero), Frank and Jacob have a conversation in an apartment overlooking the ruins of the World Trade Center. They discuss how real estate values will be damaged by the attacks and their own culpability in Monty’s crimes. The music from the film’s opening sequence returns here and combines with a zoom that takes us out of the window and allows us to gaze on the remains of the foundations of the Twin Towers. In contrast to the abstracted New York of the opening sequence, Ground Zero is shown here in documentary style, lit by the floodlights of the men working there (the scene is evocative of Joel Meyerowitz’s photographs).

8 In stark contrast to

Ground Zero Spirit, at the centre of the site an improvised American flag on a scaffold is dwarfed by the scale of the destruction. The combination of image and sound here suggests that Blanchard’s score is not a call to arms – two value systems/musical styles in conflict – but rather a dialectical synthesis, a call for a forensic look at how things are interconnected in the eerie light and emptiness of Ground Zero. By activating a critique of the system (and its victims within the US and further afield, with New York standing in for globalisation and its negative effects), the film hints that the US requires a period of critical self-reflection in which it admits that its power and status comes at the expense of others.

In realigning and augmenting 25th Hour in the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks, Lee sought to register and decipher the experience of 9/11 through the mechanism of a complex and challenging narrative of guilt, critical reflection and atonement. Monty’s personal journey can be read allegorically: the US has pursued a bare-toothed capitalism (of which drugdealers are metonymic), presided over by opportunist and self-interested politicians and corrupt corporations and financial institutions. The protection and maintenance of the system has required the condoning of clandestine, often terrorist, actions, as well as supporting repressive regimes in the Middle East and Latin America. Implicit here is the belief that activities in the past have played a role in shaping the circumstances of the present, that, in other words, 9/11 constitutes a return of the repressed. Monty’s decision to face up to these difficult facts (rather than blaming others who have had little power or role in defining this reality) offers an alternative to the overtly patriotic nationalist sentiments at play in the immediate post-9/11 aftermath.

On its release in December 2002 and into early 2003, reviewers accused 25th Hour of opportunism and insensitivity as well as heavy-handedness. Like those films with a more satirical or critical view of war, such as Buffalo Soldiers and The Quiet American, the film was discreetly sidelined, opening in only five theatres in New York and Los Angeles, and then left to languish without a suitable marketing budget, reaching 460 screens at its most visible (Spider-Man, by way of contrast, opened on 3,500 screens). More generally, the fate of the film illustrates the ways in which the dynamic, unruly reaction to 9/11 described in the present chapter struggled to gain purchase amidst mainstream offerings of escape and elision.

This chapter has demonstrated that one of the more remarkable consequences of 9/11 is the way in which the event precipitated not only an outpouring of anger, patriotic nationalism and a desire for revenge but also pleas for unity, altruism, forgiveness and love. In an attempt to capture how these different emotional states might form the basis for different possible futures, British novelist Martin Amis described the moment of the second plane strike as ‘the worldflash of a coming future’ (quoted in Randall 2010: 3). Amis’s description here recalls one of Walter Benjamin’s theses on the philosophy of history, that

the past can be seized only as an image which flashes up at the instant when it can be recognised and is never seen again […] To articulate the past historically does not mean to recognise it ‘the way it really was’…It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger. (1969: 247)

The attacks and the contested struggle to make sense of them made visible what had previously been invisible. The questions – Who? How? Why? – led many, in resistance to the view offered by the mass media, to reflect on the rise of the US as the twentieth century’s most significant superpower, on the limits and abuses of that power and on the unequal and unfair but thoroughly interdependent relationship between developed and developing countries. As well, an intensely personal form of reflection asked how the violence of the attacks also mirrors violence across the lives of those in the US who are also disadvantaged by the vagaries of capitalism. These aspects did indeed ‘flash up’, and as the films discussed here indicate, were recognised and seized upon. In this moment of crisis, two choices – parallel lines, if you will – became available: close down the uncertainty or embrace it. From the moment the terrorists struck, films were produced that sought to ask questions, challenge authority and protest against injustice. Journalists, teachers, screenwriters, bloggers, activists and filmmakers shouldered the task in different ways, but each sought to detail the complex nature of the genealogy of the attacks and the wider response to them. Even just a few days, weeks and months after the attacks, patriotic nationalism was being actively resisted. The films described here were certainly not the dominant response, but they were part of a spectrum of critical responses that, if followed, might have illuminated a path that avoided the quagmire of the ‘war on terror’ and Abu Ghraib. Indeed, the films discussed above have much in common with the more avowedly critical post-9/11 cinema that will be described in later chapters of this book. However, this critical sensibility notwithstanding, a hegemonic jingoistic nationalism did initially prevail, as the next chapter will demonstrate.