On 14 September 2001, US congressmen and senators voted almost unanimously to grant George W. Bush the power to wage war in response to the 9/11 attacks, with the invasion of Afghanistan quickly following. The subsequent extension of the ‘war on terror’ to Iraq in 2003 was preceded by a public relations campaign that claimed Saddam Hussein’s regime was a threat to US security (through its development of chemical and nuclear weapons, as well as its relationship with al-Qaida). Arguably, the cycle of patriotic war films, including We Were Soldiers, Behind Enemy Lines and Black Hawk Down, which were produced before 9/11 but fast-tracked into cinemas in the weeks and months following the attacks, consolidated the prevailing jingoistic mood (see the introduction). At the same time, a number of high-profile post-9/11 films, including 9/11, United 93 and World Trade Center, linked Ground Zero to the battlefields of Afghanistan and Iraq in ways that could be taken to imply that the waging of war was a natural, inevitable extension of the national will. Nonetheless, even in the immediate aftermath of the attacks, the diverse, often anti-war, views of those New Yorkers shown in the documentary film Seven Days in September indicated that the move to war was a contentious issue from day one. In the present chapter, a cycle of post-9/11 war films is examined as they relate to a decade of both continuous war and continuous anti-war protest.

By 2003 the ‘shock and awe’ invasions and military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq had slid into ill-prepared nation-building, much of it contracted to private companies – including Halliburton, which received single-source contracts to the value of $19.3 billion in their military support role and whose name became synonymous with accusations that the war was a self-interested exercise in capitalist expansionism (see Stiglitz and Bilmes 2008: 15). After an initial period of accommodation, the presence of US forces began to be regarded as an occupation and was fiercely contested, with insurgents using improvised explosive devices (IEDs) to harry and frustrate US troops. A protracted guerrilla war led to the US military operating in heavily fortified military bases and with increasingly indiscriminate tactics. For example, the ‘reduction’ of the city of Fallujah included the levelling by artillery and aerial bombardment of all possible enemy strongholds and the house-to-house clearance of all resistance, resulting in a large number of Iraqi civilian deaths. Atrocities conducted by US troops in Haditha, Hamdaniya and Mahmoudiya, including the rape and murder of civilians, as well as other violations of the Geneva Conventions were reported in the media. Against this backdrop news of the widespread abuse of inmates in military prisons at Abu Ghraib and elsewhere intensified criticism of the war: indeed, the popular cultural response to the news of torture cannot be easily separated from the reactions to the war more generally (see Greenberg and Dratel 2005: xiii–xxxi). The

New York Times’s retraction of its coverage of the build-up to the war in Iraq in May 2004 is indicative of how, from mid-decade, a critical view had gained traction. By 2008, Joseph E. Stiglitz and Linda Bilmes estimate, the cost of the war in Iraq was close to $3 trillion, with ever-diminishing public support (see 2008: 3–32).

A cycle of documentaries (appearing from 2004) and feature films (from 2007) marks this shift from jingoism to anti-war cynicism. Pat Aufderheide (2007) estimates that there have been around twenty feature documentaries showing the war in Iraq that have received limited theatrical releases.

44 These films critique the war in a number of ways.

Fahrenheit 9/11,

WMD: Weapons of Mass Deception (2004),

Iraq for Sale: The War Profiteers (2006) and

No End in Sight (2007), for example, take a broad historical perspective in which the Iraq War is seen as one part of a neoconservative project that seeks to secure a strategic hold over Middle Eastern oil supplies and to generate large profits for civilian contractors involved in reconstruction. These partisan and (at times) polemical films view the Iraq War as the consequence of the selfinterested, semi-criminal actions of a small group of policymakers in high office. In contrast,

Occupation: Dreamland (2005),

The War Tapes (2006),

Ground Truth (2006) and

Body of War (2007) focus on the experience of US troops and draw attention to the mismatch between the pro-war discourse and the frustrating, ineffectual and often debilitating experience of the war on the ground. Most unusually, a number of films, including

Voices of Iraq (2004),

The Blood of My Brother (2005) and

My Country, My Country (2006), in seeking to depict the war from an Iraqi perspective, exemplify how one of the demands that followed the Abu Ghraib torture controversy – that the US must seek a more reciprocal relation with those people in other countries upon which it is dependent – became a feature of post-9/11 cinema.

45Iraq in Fragments fits within this group. The film received a limited theatrical release in 2006 and won Best Director, Best Cinematography and Best Editing awards at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival, as well as being nominated for an Academy Award in 2007. The film’s title refers implicitly to Iraq’s formation in 1921 as a colonial amalgamation of ‘fragments’ of the disintegrating Ottoman Empire and to the present-day disintegration of the country as a result of the war. The title can also be read as a self-reflexive comment on the process of editing itself, whereby stories are selected and deselected and disparate images of the world are assembled into a coherent picture of a particular time and place. The film’s director, James Longley, is American but studied at the All Russian Institute of Cinematography in Moscow, and also spent time working in Russia as a journalist. These experiences perhaps allow Longley to see Iraq through the lens of Marxist concepts such as class conflict and to seek cinematic form for the expression of these concepts. In the majority of documentaries that show the war in Iraq, filmmakers foreground individual experiences (of US soldiers, generals, policymakers and politicians) and describe history as a process driven by the actions of individuals as historical agents. In contrast, Longley seeks a way of extending the range of narratives in play through including multiple Iraqi perspectives and telling the stories of groups of people who are dispossessed and marginal and have little historical agency. He also searches for ways of telling these stories so that the structural elements of class, religious difference, geographical complexity and generational change are foregrounded. His distinctive approach – which I would suggest is informed by a Marxist framework – is particularly clear in the arrangement of the stories into three, strictly bracketed, thirty-minute sections. I would contend that this narrative design, which has no corollary in the wider cycle of Iraq War documentaries, offers a challenging, thought-provoking view of the war.

The first section, titled ‘Mohammed of Baghdad’, focuses on the story of 11-year-old auto-mechanic Mohammed Haithem, who lives in the Sheik Omar district of Baghdad, a poor working-class area. It begins with a montage sequence composed of shots of bridges across the Tigris, vignettes of city life, US troops in tanks on patrol and a surreal superimposed image of a goldfish swimming in a tank. This opening is followed by a description of Mohammed’s life – his struggle at school, his relationship with his violent adoptive father – over which is layered a soundtrack composed of his thoughts, feelings and hopes for the future. Here the luminous and vivid colour palettes of digital video (and the vivid light conditions of Iraq itself) are fully explored, offering a contrast to the denotative, plain images seen on the television news and the washed out, bleach-bypass processes used in numerous Iraq War feature films. Another montage sequence – Aufderheide calls these sequences ‘visual poems’ (2008: 92) – captures the beauty, vitality, violence and confusion of Iraq under occupation, and makes the transition to the film’s second section, titled ‘Sadr’s South’. This focuses on the followers of the cleric Moqtada al-Sadr, as they rally for regional elections in the Shiite South. We follow in particular 32-year-old Sheik Aws al Kafaji, who is in charge of the Sadr office in Naseriyah. The film shows political strategy meetings, religious rallies, the Mehdi Army militia enforcing the prohibition on the selling of alcohol, a violent encounter with NATO forces and an Islamic festival which features violent self-flagellation. The third section, titled ‘Kurdish Spring’, focuses on a family of sheep farmers in the village of Koretan in the Kurdish North of Iraq. As with the first section, there is an emphasis on the experience and thoughts of children, in particular the friendship between two boys and their fathers who live on neighbouring farms. This section also shows scenes of workers making bricks in large ovens, the observance of Islamic religious custom and enthusiastic voting in regional elections amidst clear signs of a strong Kurdish nationalism.

In his production notes, Longley (2006) describes how, at the time of filming, the Sunni Arabs in Baghdad and other areas were boycotting elections and consequently falling outside the official political process. At the same time, the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution was lobbying for a separate Shiite state in the oil-rich south and the Kurds were pressing for independence and seeking to retain control over oil-rich Kirkuk. Observing these events, Longley noted that ‘the fracture lines had been drawn that would permanently split Iraq’, and so he sought out micro-narratives that would speak to these complex historical forces (each pulling in a different direction) in a suitably complex way. The film thus invites viewers to question preconceptions of the Iraq War as a singular unified event defined in relation to the US invasion and instead to hold in tension the deterioration of security in Baghdad, the strengthening of a well-organised sectarian insurgency in the South and the depiction of a region of relative peace. The documentary’s structure is driven by a concept of history in which context and deeper structures of historical change are placed in a dialectical relation with day-to-day events. The selection of these events and their placement in juxtaposition with one another is not organised via a continuity system or ordered by voice-over narration. Rather, the editing system in play is closer to that of dialectical montage, that is, the theorised approach to film editing associated with early Soviet cinema – and especially the historical films of Sergei Eisenstein – that claims that it is via editing that meaning is made, especially through the ‘collision’ of distinct and different shots that, in the mind of the viewer, combine into explosive new concepts (see Robertson 2009: 1–13). The lack of explicit linking or explanation between the different parts of the film asks the viewer to make sense of them in relation to their own knowledge of Iraq and the Iraq War. Selmin Kara observes that this dialectical relationship is also integral to the film’s sound design, noting that

the sonic contrasts among the vernacular urban noise of Baghdad streets in the segment on the Sunnis, the overpowering sectarian sounds of the Shiites, and the suspenseful quiet of the rural Kurds up north open up a dissonant space in which each fragment of the film becomes a testimony to both the cultural, ethnic and religious disquiet of the nation and the heterogeneity of its sonic landscape. (2009: 264)

Kara concludes that ‘together the fragments portray Iraq as an assemblage of discontinuous noises, sights, sounds, voices, and music, which implies that it is impossible to capture the nation (or life under occupation) in its totality’ (ibid.).

The dialectical relationship between the three parts of

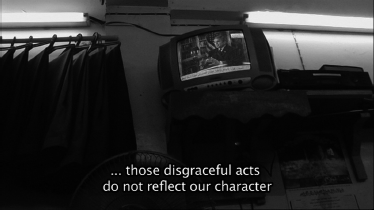

Iraq in Fragments means that Longley’s film contrasts sharply with the feature films (described below) that show the war in relation to the ‘shock and awe’ invasion stage and the ensuing military stalemate. Against this, the structure of the film asks the viewer to understand the war as a fluid, changing and complex reality within which the US invasion is formative, but not absolutely so. This is signalled through the way the dominant Western news discourse is presented in the film, where, at one point, we see Bush’s acknowledgement that prisoner abuse had taken place at Abu Ghraib military prison as part of a news report playing on a television in the background in a small textile shop – and barely noticed by the workers. In

Iraq in Fragments this pivotal news story – so central to the shaping of Western public opinion – is shown as something blended into everyday life under occupation and, crucially, relatively unremarkable.

The dialectical design of narrative structure, editing, sound design, and so on, in Iraq in Fragments extends to the orchestration of point of view. Longley spent over a year with some of his subjects and more than two years in Iraq between September 2002 and April 2005, shooting over three hundred hours of film. This commitment to inhabiting the war alongside ordinary Iraqis stands in contrast to the embedded and securitised filmmaking that typifies almost all other documentary films, which tend to approach Iraq either from afar or from within the military’s security cordons. Where films do seek an Iraqi perspective (as in The Blood of My Brother and My Country, My Country), the filmmaker is usually placed alongside primarily middleclass Iraqi families in relatively safe areas, and as we shall see, fiction films tend to emulate this embedded and securitised perspective.

Fig. 21: Revealing the lives of others: Iraq in Fragments (2006)

Aufderheide claims that

Iraq in Fragments’ montage sequences ‘underscore the way in which the foreigner’s gaze soaks up surfaces where a resident would see only background’ and signal to the viewer ‘the multi-faceted, partial knowledge of the foreign observer’ (2008: 91). In other parts of the film we are made aware (especially through the decision to leave considerable amounts of speech untranslated) of the difficulty (perhaps impossibility) of ever fully understanding the experience of the people we see on screen. Aufderheide concludes that the film ‘says much, and gracefully, about Iraqis, but much more about what Americans do not know about them and, even more, if indirectly, about the wealth of ambiguity in cross-cultural encounter’ (ibid.). While in agreement with this observation, I wish to argue that it is only part of the picture. As the above description of the film’s structure indicates, the filmmaker was keen to find ways of bringing together different perspectives, and the film attempts to offer points of view different from his own (while still acknowledging that these are, to a great extent, his own constructions). Thus, the film details a number of key characters: a 13-yearold boy in the first section, a Muslim cleric in the second, and two families (focusing on two children) in the third. We might think of Longley looking as if from their perspective, acknowledging that he (and likely the viewer) is an outsider but at the same time attempting – through a strategic editing together of voice-over, dialogue, ambient sound, music and sound effects – to offer the viewer some sense of how the war is being experienced from that particular person’s perspective. The film can here be placed alongside those described in the previous chapter, especially

Rendition and

Taxi to the Dark Side, in that it seeks a complex point-of-view system that might resist what Judith Butler calls ‘the narrative perspective of US unilateralism and, as it were, its defensive structures [via description of] the ways in which our lives are profoundly implicated in the lives of others’ (2004: 7–8).

46Longley’s focus on the child’s perspective invites comparison with the narrative trope – observable in a number of the films described in earlier chapters – of disrupted child/parent relations. In much post-9/11 cinema this trope is used to acknowledge anxiety, which is then conditionally disavowed through depictions of parents recovering their authority and protecting the children in their charge. Longley refuses this somewhat reductive construction. In one scene we see Mohammed watching a group of adult Iraqi males (including his violent adoptive father) discussing the whys and wherefores of the war: the men are cynical and angry; Mohammed’s face is blank, his brow furrowed. Here the viewer witnesses a small child trying to understand the adult world at a time of war. To this is added a voice-over consisting of Mohammed’s thoughts – a heartfelt description of his ambition to become a pilot which provides a powerful counterpoint to the difficult reality of his work as a car mechanic and the dark fatalism of the adults’ conversation. This layered and unsentimental presentation of Mohammed’s lived experience – the

mise-en-scène of the machine-shop registering Baghdad as an urban, industrialised city with a marked class divide, the father’s physique displaying injuries sustained during the Iran/Iraq War, Mohammed’s diminished size bespeaking the malnutrition suffered during the UN sanctions period following the Gulf War – speaks of the ways in which structural historical factors have impacted on Mohammed’s everyday life, making him who he is. The power of the scene stems from its recording and revealing of the contrast between grim, everyday reality and Mohammed’s thoughts and hopes for the future and provokes the viewer’s understanding that in war-torn Iraq these hopes will never be realised. Empathy and sympathy are activated (there is some ethical demand being made here that the lives of these children should be better than they are), but this response conjoins with the intellectual work demanded by the film in its entirety; these children are historical subjects and their futures will be dictated by the interplay of forces modelled by the film’s dialectical structure and composition. Here the film demonstrates something of the searching quality of

Parallel Lines, the interconnectedness and structural analysis sought by

Syriana, and the awareness of otherness displayed in

Rendition. This combination – a sharp riposte to the reassuring parent/child melodramas at the centre of

Man on Fire and

War of the Worlds – arguably makes

Iraq in Fragments one of the most important post-9/11 films.

Fig. 22: An Iraqi child’s perspective of war: Iraq in Fragments (2006)

Following the documentary film cycle, a cycle of Iraq War feature films entered production, appearing from late 2007 and into 2008, including

GI Jesus (2007),

The Situation (2007),

Home of the Brave (2007),

In the Valley of Elah (2007),

Redacted (2007),

Badland (2007),

Grace Is Gone (2008),

Conspiracy (2008),

Stop-Loss (2008) and

The Lucky Ones (2008). Both

The Hurt Locker (on wide release in the US from mid-2009) and

Green Zone originate in this period, but the releases of both were held back after the poor box-office performance of their predecessors.

47 Most of the films are contemporaneous, that is, they are set in the period of the war immediately preceding their release, a period in which jingoistic ‘mission accomplished’ rhetoric confronted the reality of a strengthening insurgency and public recognition of prisoner abuse and atrocity. Douglas Kellner argues that ‘the cycle testified to disillusionment with Iraq policy and helped compensate for mainstream corporate media neglect of the consequences of war’ (2010: 222).

The remainder of the present chapter is devoted to a close reading of one film from this cycle,

In the Valley of Elah, and the placing of this film and the cycle as a whole in relation to the wider US war film genre. During World War II, the US war film functioned as propaganda, celebrating individual and group heroism, the sacrifice of individual desires to higher ideals and goals and the effectiveness of military command and technology, as well as emphasising the importance of strong leadership and celebrating war as an exciting and spectacular experience, and as a (male) rite of passage. The war film typically embodied a severely restricted point of view (usually via the experience of a small military unit or patrol) and a prejudicial construction of cultural otherness. A grim, bloody realism was also an essential element of the genre, reminding the viewer that the nation (and the ideals it embodies) was, and continues to be, built on the honourable sacrifice of young citizen soldiers. In post-war films, these propagandist elements (what Thomas Schatz calls ‘Hollywood’s military Ur-narrative’ (2002: 75)) remained a key generic feature, with even the bloodiest war films tending to show war as a ‘progressive’ activity, entered into reluctantly but ultimately proving necessary and productive. The subsequent experience of losing a war in Vietnam marks films such as

The Deer Hunter (1978) and

Apocalypse Now (1979) which challenged and questioned many of the genre’s core myths (while never escaping them completely) (see Boggs and Pollard 2007: 90–1). However, after a brief cycle of what might be considered critical (if not resolutely anti-war) films, earlier features of the genre (and the positive view of war enshrined in it) reasserted themselves. A series of revisionist war films – from the

Rambo trilogy (1982, 1985, 1988) to

In Country (1989) – depicted the war primarily through the experience of the ordinary combat soldier (or grunt) and alleviated the traumatic experience of the veteran through the application of discourses of therapeutic overcoming (see Sturken 1997: 85–122). Subsequently a cycle of films released in the late 1990s and early 2000s – including

Saving Private Ryan (1998),

Pearl Harbor (2001) and

We Were Soldiers (2002) – presented war in ways proximate to the propagandist genre staples of the 1940s (see Westwell 2006). This reclaimed sense of war as a noble and necessary activity interlocked with forms of banal US nationalism in the period immediately following 9/11, prompting Andrew J. Bacevich to argue that in the contemporary period ‘Americans have come [once again] to define the nation’s strength and well-being in terms of military preparedness, military action, and the fostering of (or nostalgia for) military ideals’ (2005: 2).

Significantly, though, Bacevich’s claim was made before the release of the cycle of Iraq War films noted above, raising the question: do his claims still hold true? Post-Abu Ghraib, is US culture governed by what he calls the New American Militarism? While Kellner’s view of the cycle – that the films are engaged in anti-war protest – would suggest that the answer is no, analysis in this chapter suggests that such unguarded optimism may be misguided.

In the Valley of Elah contains many elements that would seem to be a very difficult fit with Bacevich’s claim, especially the acknowledgement of atrocities committed by US troops and the depiction of generational angst and republican crisis. By showing these aspects of the war in Iraq the film appears to function very strongly as critique. However, the way in which the film shows that (finally) atrocity can be recuperated is, in the final instance, reconcilable with the New American Militarism, and serves as a further example – following

War of the Worlds and

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close – of the way in which parallel lines converge in the service of hegemonic constructions of the war in Iraq and war in general.

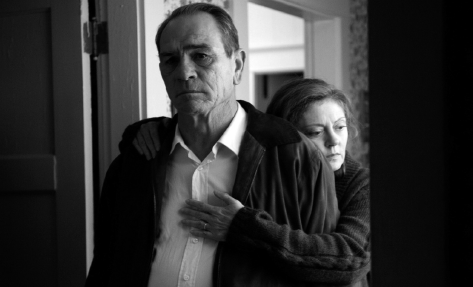

In the Valley of Elah, which is based on events described by journalist Mark Boal in an article for Playboy (2007), focuses on the experience of Hank Deerfield (Tommy Lee Jones), a retired former military policeman and Vietnam veteran, as he investigates the disappearance of his son Mike (John Tucker), an Iraq War veteran. The film shows Hank’s investigation revealing that Mike was murdered by his fellow soldiers. The scene in which Corporal Steve Penning (Wes Chatham) describes to Hank, without emotion or remorse, how he and his fellow soldiers murdered Mike and dismembered and disposed of his body shows how the war has reduced young men to sociopaths unable to feel empathy or even recognise the loss of their ethical bearings. In the same scene Hank is told that his son was a drug addict and alcoholic who took sadistic pleasure in abusing Iraqi prisoners. Here, as with Redacted, which is also based on real events and recounts the rape and murder of an Iraqi girl and her family, the film seeks to acknowledge the role of US troops, and the culpability of the US more generally, in war atrocity. This leads Joan Mellen to claim that the film shows how ‘America’s young men drilled and educated to fight America’s expansionist foreign wars have been morally damaged at the same time as the national ethos’ (2008: 24). Adding to this bleak view of post-Iraq realities, Deerfield’s investigation takes place against a backdrop of apathy and uninterest: as Martin Barker notes, ‘the film is full of people – the police, the military, men at a strip club, some café owners – who simply do not care’ (2011: 29).

The details of fratricide and atrocity are revealed through the perspectives of different family members and via generational difference, especially the relation between fathers and sons (and in more dilute form, mothers and sons). The first perspective is that of a grief-stricken and guilt-ridden father. In Boal’s

Playboy article Hank is described thus: ‘Staff Sergeant Lanny Davis, retired, a United States Army veteran, husband, father and proud owner of a tidy ranch home in serene St. Charles, Missouri, lives a life you could call squared away’. The film shows Hank’s carefully tended garden, sharply pressed shirts and carefully organised luggage, the film’s

mise-en-scène cultivating the sense of Hank’s character as ‘squared away’ found in Boal’s prose. Tommy Lee Jones’s performance also seeks to articulate this sense of a man deeply committed to a military ethos, leading Michael J. Shapiro to note that Hank’s ‘body and his verbally expressed allegiance to military protocols…convey the ways in which the Deerfield home is militarized’ (2011: 119). Indeed, the film has identified Hank (as synonymous with a military value system) as the source of the problem: he has made his son in his own image and this sense of self has then been found to be irreconcilable with the experience of the war in Iraq. Mellen notes: ‘When Mike telephoned and pleaded, “Dad, get me out of here!” Hank, a Vietnam veteran, urged him to carry on. That call, repeated several times in flashback, expresses cinematically the father’s sense of his own guilt’ (2008: 26). In contrast to the reassuring return of patriarchal authority found in most films that depict disturbed parent/child relations post-9/11, here the father’s failure to protect his son cannot be redeemed.

Two further points of view – those of a mother in each case – give shape to the film. The first is that of Hank’s wife, Joan (Susan Sarandon). Shapiro notes how the

mise-en-scène brackets her domain (the kitchen) from the rest of the house, which is associated with Hank (2011: 119). Although, on the surface, Joan is supportive of her husband, the film hints at how she resents Hank and the military, identifying his upbringing of their sons as the cause of both their deaths. As Shapiro puts it, ‘For Joan, her son’s death is a result of the way her militarized household left him no option other than enlisting. As she puts it, “Living in this house, he sure never could have felt like a man if he hadn’t gone”’ (2011: 122). Joan’s quiet grief – ‘Both of my boys, Hank?’ she cries at one point, ‘You could have left me one’ – clearly attributes blame in a way that confirms the impression conveyed through the narrative that a military ethos produces the kind of destructive violence unleashed in Iraq and felt by families of soldiers killed or physically and psychologically damaged by the war. The second point of view is that of police detective Emily Sanders (Charlize Theron), who helps Hank investigate his son’s disappearance. The real-life figure on which Sanders is based is described in Boal’s article as a large, bluff middle-aged man named Drew Tyner. By rewriting the character as female, the film doubles Joan’s critical gaze, thereby reinforcing (from another female’s/mother’s perspective) a point of view external to the world of masculine militarism. The final shot of the harrowing central interrogation scene is a cutaway to Sanders’s reaction to Penning’s confession. She holds the gaze of the confessing soldier and then averts her eyes. Refusing to align herself fully with Hank’s shocked, guilty reaction, her turning away seems to offer some kind of alternative moral/ethical position whereby Penning’s sociopathy and Hank’s suffering are shown to be connected. With no easy way of detaching the two realms of experience, it is necessary, the film suggests, to look elsewhere, to seek an alternative viewpoint.

Fig. 23: Atrocity and post-traumatic stress disorder: In the Valley of Elah (2007)

Taken together, these aspects of the film (a willingness to show atrocity and to reflect on the structural elements in US society that underpin the military and that create the conditions for such atrocity) culminate in Hank’s decision, in the film’s final scene, to fly the US flag upside down: something that he has earlier explained to an El Salvadorian caretaker is a signal that there is an emergency. Barker observes that

over these final scenes, a slow ballad accompanies Hank’s acts. It is a woman’s lament that from the moment we are born we are touched by death. The final image is of a dead body in the road, captioned with the words ‘For The Children’. (2011: 31)

Thus, the film shows the republic in crisis, a theme in post-9/11 cinema observable through the documentary films described in chapter one, the conspiracy films in chapter three and the torture films in chapter seven, and which is appropriated late in the decade as a principal response to the war in Iraq.

Can it be concluded from this that In the Valley of Elah challenges a wider societal militarism through an unflinching depiction of atrocity and the structural rootedness of this in a certain male military mind-set? Yes, to a point. However, the focus on young soldiers so brutalised by their experience in Iraq that they have spiralled into abuse of drink and drugs to allay their traumatic experiences may also activate the therapeutic discourse at work in the films described in chapter six, and this resolute focus on the suffering of US troops (extended here to the wider family) also constitutes a turning away from the acknowledgement of the other demanded in films such as Iraq in Fragments.

Another look at the narrative structure of

In the Valley of Elah opens up the potential for a more qualified reading of its description of the Iraq War. The events depicted in a fleeting image and aurally at the start of the film (where they remain opaque) are finally revealed as Hank discovers and has decoded the camera footage from his son’s mobile phone. The footage shows that during a military operation a child is run over and left to die by the side of the road. This provides the point of origin for Mike’s descent into despair, and subsequent desensitised, sadistic behaviour. In a world in which a child’s death is barely registered, the moral bearings of young Americans in a war zone are quickly lost. Throughout the film Hank is haunted by the phone call made by his son from Iraq in which Mike pleads for help in the aftermath of the death of the Iraqi child by the roadside; the reason Hank is troubled is that he failed to offer Mike any counsel or support. Here, again, we see how an intervention (support, understanding, empathy) might have headed off Mike’s subsequent breakdown and violent sadism. As Barker notes, ‘Mike’s agony over [the death of the child] becomes the post-facto explanation for his abusive behaviour towards prisoners’ (2011: 30). Indeed, in another scene camera phone footage shows Mike playing with Iraqi children. Barker also draws attention to the fact that Boal’s article considers the possibility (revealed to him by more than one source) that the real-life soldier Mike is based on was killed because he was about to report his fellow soldiers for their involvement in the rape of a young Iraqi girl (see 2011: 81–2). That this event – tackled head on in

Redacted – does not feature in the film suggests that the filmmakers had sought to amend the nature of the atrocities committed in order to retain some audience sympathy. Similarly, Mellen reports that ‘in a scene from the shooting script that did not make the final cut, Mike visits a girlfriend now in hospital, a double amputee returned from Iraq. The parts he was interested in still work, he tells her’ (2008: 31).

Cutting this out suggests a toning down of Mike’s capacity for violence and casual misogyny to retain the possibility of redemption. Barker argues that ‘this whole process of misleading and disclosing creates a space in which soldiers’ cruel and inhuman treatment of Iraqis becomes excusable. We see their brutality simply as a mistake arising out of stress and sickness’ (2011: 32). For Barker, Mike

becomes an exemplar of ordinary soldiers, basically good men, but stressed beyond their limits by the war. Their murderous behaviour, their torturing of prisoners becomes explicable, even excusable, because they must be suffering from that syndrome known as PTSD. (2011: 82)

Here the film keys into the wider discourse: for example, follow-up stories to the iconic ‘Marlboro Man’ photograph – which showed a US Marine taking a cigarette break during desperate fighting in Fallujah – described how on his return home Marine Lance Corporal James Blake Miller had succumbed to PTSD. As such, an image of heroic stoicism segued into a more complex narrative of psychological injury and recovery, and as a result a questionable military operation that resulted in considerable loss of civilian life is subsumed by the wider therapeutic discourse as shaped by the media, including the cinema. Also part of this wider response, Boal’s follow-up articles in Playboy focus on PTSD as experienced by troops who had served in Iraq. Indeed, Boal’s ‘The Man in the Bomb Suit’ (2005) provided the basic plot of The Hurt Locker, the most successful, and arguably the least critical, Iraq War film.

Aligned with critics of the therapy paradigm (see Seeley 2008; Fassin and Rechtman 2009; see also chapter six), Barker argues that PTSD ‘shifts uneasily between being a medical category, a legal manoeuvre and a fictional explanatory device’ and that its centrality to post-9/11 culture is ‘part and parcel of a depoliticising tendency, which needs people to be victims before they can be said to need help’ (2011: 83, 86). Put simply, ‘PTSD has come to function as a key metaphor for America inspecting itself within safe margins’ (2011: 99). A key aspect of this is the way in which PTSD licenses dialogue and agreement between those with differing political points of view (Barker notes how left-liberal cartoonist Garry Trudeau and Republican John McCain both rely on the PTSD paradigm (2011: 87)), leading Barker to argue that the therapy paradigm forms a ‘bridge across conservatives and liberals in America’ (2011: 99). As such, PTSD as it appears as a narrative trope in the Iraq War film cycle is a key marker of one of the main themes of this book, namely the way in which a left-liberal critical perspective cedes ground to the right, thereby backing away from the radical direction critique might otherwise lead, with therapy in this case the key ground upon which the convergence of seemingly irreconcilable positions takes place.

48So, how might we reconcile these two claims regarding the film? Is it a forensic account of US atrocity and the dangers of a militarised domestic realm? Or does the leeway permitted by the PTSD trope constitute a turning away from, and even a redemption of, these difficult issues? Of course, in this specific case the answers to these questions are not clear-cut – the film is ambiguous and contradictory. However, things become clearer if the film is considered in the context of the cycle to which it belongs, and the relation of this cycle to the war film genre more generally. In an article for the

New York Times, A. O. Scott (2010) tracks the widespread denial of politics in Iraq War films and argues that this is a consequence of a focus on PTSD leading the Iraq War (like Vietnam before it) to being reduced to a psychologised and thus ahistorical experience. Scott is here referring to the way in which the difficult legacies of the Vietnam War were subject during the 1980s to a widespread revisionism as part of the consolidation of the wider culture of Reaganism and the rise of the New Right. This revisionism sought to reclaim credibility for the military and rebuild national self-esteem. One of the key strands of this revisionism was a focus not on the war itself (and its political, geographical and symbolic complexity) but on the suffering of the Vietnam veteran, who, according to revisionist logic, had merely done his patriotic duty in difficult circumstances. In relation to cinema, a number of films showed Vietnam veterans overcoming their struggle with PTSD, and this process of ‘healing the wounds’ became the dominant metaphor for rendering the war less divisive a decade after its end (see Beattie 1998: 142). As a result of this process, Scott argues, and in continuation with many others, by the late 1980s the divisive and troubled memory of the war in Vietnam had been settled and this enabled a reclamation of foundational narratives of masculine, military, technological and political superiority, arguably ensuring the necessary preconditions for further wars in the 1990s and 2000s. Scott suggests that a similar strategy (this time working contemporaneously with the war rather than following it) is at work in relation to the Iraq War, with the resolute focus on the suffering of US troops used as a way of screening off more complex views of the war. The US is figured here as a skilful, decent, young soldier who has engaged in war in good faith and then suffered great psychological harm as a result of their experience.

At first glance, a move towards resolution of this sort is not an obvious feature of In the Valley of Elah. The film strikes a provisional note: the redemptive ending is deferred because the war is still being fought, and as a result of the film’s drawing of attention to the structural dimension of militarism, the lines of responsibility and recuperation remain unclear. Kellner notes how in The Hurt Locker, Home of the Brave, The Lucky Ones and Stop-Loss the characters display a compulsion to return to the war. This suggests both an incompleteness and a desire for a different kind of resolution, pointing to the way the cycle acknowledges difficulty but also retains the possibility of a positive outcome (2010: 223–33). However, this critical and provisional quality notwithstanding, the wider cycle does tend to signal that a therapeutic narrative resolution may, with time, be possible: for instance, in Grace Is Gone a father whose wife, Grace, has been killed while serving in the military in Iraq takes his daughters on a road trip to Florida; in the final scene he visits the ‘Evolving Planet’ exhibit at the Enchanted Garden theme park, the mise-en-scène suggesting acceptance and personal growth. The redemptive trope can be seen in Brothers, a film about the war in Afghanistan, which ends with Captain Sam Cahill (Tobey Maguire) finding the courage to tell his wife (again named Grace) of the atrocity he has committed (the murder of a fellow soldier, a fratricide that recalls the murder of Mike in In the Valley of Elah). The final scene shows Grace’s and Cahill’s families pulling together to help heal the wounds the war has inflicted. If the films are read alongside one another, In the Valley of Elah’s guarded movement towards redemptive possibility segues into the more determined therapy narrative of Grace Is Gone and Brothers, thereby enfolding the figure of the returning traumatised combat veteran in discourses of healing and forgiveness.

So what is to be made of claims of an all-pervasive New American Militarism shaping US popular culture in the early twenty-first century? This chapter has demonstrated that the late 2000s witnessed the release of a cycle of films operating at the absolute limits of the war film genre. Within the set of bounded possibilities available to filmmakers working in Hollywood, and at a time when US troops were still being killed on the battlefield, a cycle of war films appeared that could be said to be largely critical of war. Filmmakers have been willing to face up to the facts that US troops have committed atrocity, that the wars have not been a success, and may even have been counter-productive, that the main beneficiaries have been large US corporations, that jingoistic constructions of national identity can be harmful, and so on. Taken together with the myriad documentaries focusing on the war, this critical coverage is almost without precedent, leading one right-wing critic to dub the cycle ‘Bin Laden cinema’ (Philpott 2010: 326). However, and crucially, many of the films that might be said to display this new complexity have been unpopular with audiences in the US (Barker labels the cycle ‘toxic’ (2011)), and the dominant trope emerging is one of the war being brought home, that is, figured as the experience of individual soldiers suffering PTSD, and made available to discourses of forgiveness and healing. This therapeutic closure – described also in chapter six – as well as the reclamation of the possibility of purposeful military action, also inflects

Zero Dark Thirty, described in the next chapter.