The story for the naming of the Atlanta suburb of Buckhead says that a well-known local killed a large buck and displayed it publicly; the name came to designate the entire area.

The story for the naming of the Atlanta suburb of Buckhead says that a well-known local killed a large buck and displayed it publicly; the name came to designate the entire area.

A few days before my expected start date, I casually strolled into the Ted Turner-run metropolis of Atlanta. I wasted no time unpacking my duct-taped boxes in my new, modest, six-hundred-square-foot apartment, sandwiched between restored buildings on the edge of Buckhead. My apartment was squeezed between Sydney Marcus Boulevard and the 400 freeway. It bordered a shady neighborhood that had plenty of low-rent strip clubs and smut shops, but more importantly, was only a five-minute drive north to the hotel, on Lennox road. Once I tackled the stack of boxes, I busied myself assembling my leftover college furniture along with a newly-bought table and chairs from Target, in between countless runs to the Dollar store. My phone rang. It was my new boss, asking me to come in for a meet-and-greet before my official orientation date.

I changed out of the yellow, four-pocket guayabera that I picked up from a shoeless street vendor in a back alleyway of Havana for pennies on the dollar. It was only fitting to change into a pair of khaki pants and a polo shirt, which I had to dig deep for. After a quick drive to the hotel, I pulled into the interior of the polished, copper porte-cochère in my recently-washed, Isuzu Rodeo SUV. I already felt out of place among the luxury cars that were ahead of me in the valet line. A well-groomed and polished gentleman opened my car door and welcomed me to the Ritz Carlton, Buckhead, and wrote my last name on the valet ticket. Not but fifteen steps later, both twelve-foot, wooden, mahogany doors were opened in unison by a set of men dressed in cobalt-blue tuxedos and gold trim, with dangling tail vents. The gentleman to the right made direct eye contact and said, “Good afternoon. Welcome to the Ritz Carlton Buckhead Mr. Gilbert!” How’d he do that?

I stood in the hotel lobby all alone, while business men left their power lunches and new hotel guests checked in. The entry way was opulent, with traditional English furniture and fresh flowers on each side table. I was approached by the concierge, who had come out from behind his little cubby-hole window to assist me. He looked me over in a millisecond and asked, “Excuse me sir, how can I assist you?” I simply stated, “I am a new kitchen hire and here to meet my boss.” “Please have a seat, Mr. Gilbert,” and the next thing I know, a Lobby Lounge server brought me a Ritz Carlton-branded bottle of water with a lemon, lime and blood orange on a side plate. I went to cross my legs to appear comfortable, but then it dawned on me—I had no socks on! Not having worn any in more than four months, I apparently overlooked them in my excitement to get out the door. Great. While I am attempting to allay my wardrobe oversight with repeated thoughts of, “It’s just a meet-and-greet …” I continued to scan the lobby and take in the attention to detail it represented, from visual aesthetics to the unexpected greetings being offered to guests. My own “attention to detail” was becoming an elephant in the room for me.

Before I knew it, a youngish-looking, but haggard, bone-thin man appeared from the lounge area just off to my right, wearing a starched, white, chef jacket with blue piping and pressed black pants. I saw the embroidered name just above his left breast pocket, below the signature Ritz Carlton horse. I stood up with excitement to greet the baggy-eyed chef, who looked like a pale version of the grim reaper or a tired Steve Buscemi; I extended my right hand as I was welcomed once again.

He thanked me for coming in to wrap-up some additional human resources paperwork, to get fitted for jackets, and most importantly, to meet some of the other key players in the operation. The sounds of the piano music were becoming distant as we headed toward the north hallway. Before my foot crossed the carpet threshold, he stopped me and said, “Guy, it would be nice if you put on socks …” I was already feeling like a fish out of water, but he sure did drive the gaffe right into my flesh. All I could do was agree. So much for trying to hide the elephant.

The hotel tour was confusing. We went in and out of various doors and elevators that were all connected in the back of house. The field trip through the hotel was interesting. I watched nearly every female pass by and say, “Hi Chef!” in a bubbly, teen-age voice. It was hard to tell what was going on, but it didn’t take long before the details came out. This metal-head rock star was a proud Canadian, and once I shared that was also my birthplace, I was no longer American in his eyes. Jacket-fitting and paperwork having just been checked off the list, it was now time to meet the rest of the staff of the elite establishment. The most memorable moment that day (aside from the socks comment) was meeting the illustrious, French-born pastry chef.

We walked through the small, humming, Café kitchen, where I first met The Café’s chef, Robert. This pear-shaped Frenchman spoke a total of five words of English using grunts and plenty of “ahhhh’s” and “ugggghs.” We then passed by the In-Room Dining department, where a voluptuous German princess was in charge. We both stood there saying hello, clearly experiencing sexual tension. I had just been introduced to the lovely Anna Bella.

We went through the main kitchen and stepped into the “igloo,” or garde manger kitchen. I met the one and only “food magician,” who had probably been working at the hotel since they installed the first light fixture. Phillip was a mainstay there and had been through countless executive chefs and even somehow managed to put up with a crazy Vietnamese cook, Tu, for years.

Finally, our last stop was the pastry kitchen, which was separated by the wide, banquet corridor lined with countless hot-boxes from the afternoon’s function. Somewhere between the divided world of savory and sweet we came across a guy that appeared to have eaten ten-too-many servings of butter cookies. This guy had three shiny gold teeth—one with a dollar symbol etched into it—and was dressed in a cheap, polyester, off-white shirt and narrow black necktie he probably bought at Elwood Blues’s garage sale. It was a good thing he wore the hotel-issued “lab coat,” concealing from higher ups most of his sartorial choices. Perhaps it would have sent the wrong message—he had spent all his money on his ore-filled mouth. This was the head steward, Willy, who was proudly born and raised on the south side of Atlanta. He turned out to be a great guy, however, keeping a count of banquet plates, which was his job, was never his forte. Before I could get much more than a hello in, he was already receiving a brutal, but friendly, tongue-lashing from the boss, my new chef. All this was the buildup for meeting the Frenchman.

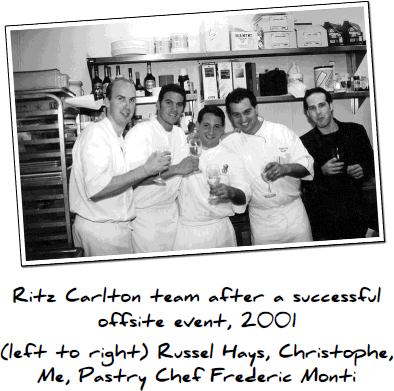

We were greeted, before my foot passed the first tile line of the pastry shop, with a screaming, smiling Frenchman:“What the fuck do you want?” Ganley, my tour guide that first day, was quick to fire off that he had yet another Canadian joining his team. Chef Fred’s response: “I don’t care; neither of you will ever be French …” and that was that. I came to understand that upper-level management at the time, including the executive chef, were all second and third-generation hoteliers and restaurateurs from Lyon.

Ganley, to whom I reported directly, was a 27-year-old, Player cigarette-smoking, rock star and lothario who grew up in Windsor, Ontario, the armpit of Canada. He worked several years in Toronto and spent the better part of his young adult life working his way up the ranks at various Ritz Carlton Hotels. I immediately fell in the groove with his leadership style and his commitment to the kitchen crew.

I worked through the first holiday season in the banquet kitchen and learned the ropes of the operation, the company, and their expectations. Ganley continuously gave me golden nuggets of advice at random times. I would share my thoughts with him at will, or when I was hesitant to speak up or try something different. He used to say, “Guy, sometimes you just need to throw your dick in the fan!” which in his twisted world equated to, “Don’t stick your toes in, just jump!” Ganley has passed along those famous words to hundreds of cooks over the years. I have met other chefs around the globe and as soon as we connect that we know Ganley, it’s the first thing that gets repeated. This guy has created some type of sick, twisted, chef subculture!

Ganley ran a tight ship, but even when we made mistakes, he never came down on us if we were trying our best. That leadership style built a strong core culture in the kitchen and created a team of people that always challenged each other. We pushed the boundaries of creativity and expanded our philosophies on food. Every day there was a new saying or phrase that captured the moment we were all in together. We were a bunch of uncouth pirates when in the kitchen, but always mindful of the setting and standards we had to uphold. What boss at a Ritz Carlton, with black bags under his eyes from being so sleep-deprived, strolls up to employees and can get away with sexual innuendo, racial teasing and religious jokes? You guessed it, Ganley. Everyone knew that he gave so much of himself to each person, that his verbal license was never taken to heart.

His stories of “downward, dog-posing” chicks of all ethnic backgrounds and his life lessons from being a “rock-star chef” would only keep you laughing and engaged, simply waiting for more! He had a driving intensity that kept everyone on edge, and just when you would think the guy is done, he would sneak out for one of his Player cigarettes and pop back for another several hours of hard work and comedy! Ganley. The man. The myth. The chef-legend.

Over time, Ganley became a mentor for me in many respects. The more we got to know one other, the more he let me into his personal experiences. I went to him after my 90-day probation period and rambled something along the lines of, “I think I should qualify for a sous-chef job, since I have the experience and two degrees.” He turned to me and said, “The years you spent killing yourself so far is what got you into this hotel. You don’t know shit! Get back to cleaning the lobsters for the party.” Like any young hotshot, I thought I knew it all. He would put me in my place in a moment.

This was no mom-and-pop operation. We ranked as the best Ritz in North America, we won accolade after accolade, and we not only had a reputation to surpass every day, but were the flippin’ country club for Horst Schulzy (the famous hotelier, former president and COO of Ritz Carlton) and the corporate office! Everything had to be beyond perfect, no excuses, no compromises.

This step in my life was invaluable and added a building block for the future. I was promoted to chef saucier at the hotel within 10 months and had earned my stripes, along with a bump up to $11.25 an hour. I felt like I was a king. Meanwhile, after nearly a year of Ganley relentlessly riding my ass, he was slated for a transfer to the Ritz Carlton, New Orleans, as executive sous-chef. He had been mentoring me to understand what it took to climb the ranks from schmuck cook to sous-chef. I learned that if I wasn’t there an hour early, then I was late! He was tough, but fair, and to this day I still appreciate that. Furthermore, he demonstrated that job transfers, changes, and new challenges were the norm in the Ritz culture.

My mind began wandering, between bouts of exhaustion and adrenalin, to the vision of other Ritz properties on sunny beaches, where I could advance my position and perhaps have a life outside of the kitchen. Every time I reached for white pepper, I was grasping a pinch of Caribbean sand. Each glance of tropical fruit or flown-in fish conjured memories of bright sun and the adventures of the recent past. One day I impulsively made mention to the Executive Chef my interest in other properties with tropical settings. I had a friend in St. Thomas who periodically reminded me, during occasional, ill-timed phone calls, “what I was missing” in the warmer parts of the world. Work didn’t stop at Buckhead and I all but forgot I had made this casual comment to the Chef.

Relentless days and endless nights blended together; I spent several weeks without seeing day light. I was a train wreck but never thought of slowing down! One morning at 4:00 a.m. I had a breakdown; I sat on the floor at the end of my bed and just started crying. I had no idea what was wrong with me and quite frankly, I felt completely beaten down at that moment! Was this just the “exhaustion” malady, written about in gossip rags? I got my sorry ass up off the ground and headed into work, nearly falling asleep at the wheel; fortunately, it was a short drive. Maybe this was not a smart move, but with bones to slow-roast and stocks to start, production had to get done! In hindsight I should probably thank my father for repossessing my car back in high school, one of the many incidents with my parents where I got the ability to pull myself together and face the facts with the right work ethic.

I finally started to wake up to the sounds and smells of simmering liquids, aromas of 300 sheet pans filled with cooked bacon, and my tenth cup of coffee. Trying to stuff the exhausted reaction of the early morning hours into a box, I plunged into my work with a vengeance. At 6:00 a.m. the Executive Chef, who—once I became the chef saucier—had coffee with me for three minutes each morning, rolled into the kitchen. This third-generation French chef lived up to his reputation, not only for being intense but for always raising the bar. He knew when to turn up the heat, no pun intended.

That morning I strained the silky-sheened, veal jus that had been slow-simmering overnight, caramelized the mirepoix (chopped onions, celery and carrots) for the next stock, and had twelve different sauce reductions working in anticipation of the next two days. He walked in, all intense, and opened his office door. Then I saw the fury on his face, so I kept my head down until he was prepared to say hello. From five feet away, a bellowing voice grabbed my attention: “David, get in here!” As I shuffled in, his head shot up and he commanded me to get two espressos and come back because he wanted to talk to me. Not knowing what the hell was going on in that crazy French mind of his, I did just that. I proceeded into the office and he stood up and threw some papers right at me: “Look at this!” “Yes, Chef!” I replied.

It was the JD power, quality rating scores; we had slipped in only one area by the smallest of margins and excelled in all others. He went into a rage, yelling, “What is the fucking problem here?” Meanwhile, being so tired and showing such little emotion, I was not sure what response he wanted from me. Did the Chef just want to vent? How do I know? Maybe he didn’t get laid; maybe he didn’t take his meds? Maybe his dog pissed on his breakfast croissant? How the hell did I know … ? I simply stood up and looked him dead in the eyes and told him, “Chef, I am in this for the long haul; we will exceed your expectations.” He sat down and said, “You have some big balls Da-vide, and that’s what I wanted to hear; you have a call Tuesday morning with the Executive Chef in St. Thomas for a sous-chef position.” I was floored.

How this guy operated was beyond me, but he always pushed his staff to the bitter end of sanity. The days that followed were a mixed bag of regret: what if St. Thomas doesn’t pan out? Maybe I would get treated with resentment for looking elsewhere. What if it does work out, and I walk away from the best-of-the-best excitement? Walking out of the hotel that night, I passed a small entourage of folks tending to a famous, now unconscious, rock star (sorry Ozzy!). I was struck by the image of myself as a protégé of Ganley’s army of walking dead. Looking over photos from Mission Maya in the middle of the night, after a grueling shift, the possibilities for the future began to crystallize like sugar on a Georgia pecan pie. In the two-and-a-half years of learning and advancing—and acquiring an appropriate pair of socks—I had overcome any doubts that I harbored from my many conversations with Ganley. He was talking directly to me and my mixed emotions, when he said, “Some people have it, and some people never will.” “It” had become embracing change and new opportunities, and mastering them all in turn.

My years in Buckhead were spent primarily in the kitchen, often passing on a social life and going weeks without seeing the sun. Through two-plus years of sleep deprivation and self inflected pity parties, I learned the foundation of what it takes to be the best. This road isn’t the easy ride or quick rise to fame, that so many culinary schools pitch as pipe dreams to capture prospective students, attempting to coerce them to “just sign the dotted line.” The journey is long and slow and—in reality—is no different than developing the right flavors in a perfect fond de veau.

100 lbs. veal knuckle bones

1 bunch of celery, rough-chopped

6 carrots, rough-chopped

6 onions, diced large

1 handful of fresh thyme

8 oz. tomato paste

1.5 gallons red wine

12 pepper corns, crushed

3 leeks, whites only (for albumin content), split in half

15 garlic cloves, smashed

Roast the bones for 6 to 8 hours at 250 degrees Fahrenheit, until dark brown (avoiding caramelization of the marrow). Add the garlic, onions, celery, and carrots for the last hour and a half of roasting. In the stock kettle, add the wine, tomato paste, and thyme until 2/3rds reduced (by volume). Pour off the excess fat from the bones (reserve for confit veal shoulder), and place the bones into a stock kettle. Add cold water and leeks, and keep on a VERY low temperature until bubbles begin to break the surface. Set it off the burner, and skim fats and impurities from the surface carefully, with a ladle. Allow stock to gently simmer for 24 hours, removing impurities every hour. Strain through chinois (a conical sieve) or a fine mesh sieve, with crushed black peppercorns. Refill the stock pot 2/3 of the way with cold water and repeat this process for 24 hours, saving the remouillage or 2nd run, to replace the cold water for the next new veal stock.

My lunch is a little more than halfway gone now and I’m getting the hang of how to eat this simple, but complex, dish. I take a short break and walk into the sea to cool off before I continue. The further I let the current take me, the more within reach the island formations seem. “Chai way-la tao rai?” (How long does it take?) I use the single-ply napkin to wipe off the salty water from my sunglasses. Time here really doesn’t seem to matter, I reflect, as I glance over my right shoulder at the vacant, long-tail boats. With that thought, I peel off my dive watch to reveal slightly paler skin underneath, and shove it hastily into my pack. I pick the chopsticks back up and wonder what life would be like if I were scuba-diving here under the water …