1

Race Strategies and the Politics of Urban Development

Each day tens of thousands of people pass through the city of Chester, Pennsylvania, making their way to destinations along the mid-Atlantic seaboard from Boston, Massachusetts, to Washington, D.C. Interstate 95 and Amtrak’s Northeast Regional passenger rail line cut right through Chester, and most travelers, speeding along in cars or in trains, are oblivious to yet another blurry patch of redbrick row houses and old, abandoned factories seen repeatedly along their routes. The same holds true for most commuters, shoppers, and others who live in Greater Philadelphia and have very few reasons to think about (much less stop in) Chester. For many of them, Chester is the city “that used to be nice,” a forgotten, dangerous, and mostly deserted place to be avoided, or a highway marker just south of Philadelphia, north of the Delaware state line, and on the edge of leafy and very wealthy Delaware County.

Since 2005 local economic development officials, politicians, business leaders, and developers have worked tirelessly to make Chester less a place to drive through, ignore, or intentionally avoid and more of a destination for middle-class visitors and eventually residents. Their strategy has been to capitalize on the city’s location along major transportation arteries and open a riverfront casino, a waterfront esplanade park, and a soccer stadium for a major league expansion team financed by a mix of public dollars, tax abatements, and private investment. Suburban Delaware Valley gamblers now flock to the casino in great numbers, quickly moving from the Interstate highway to a covered parking garage. Soccer fans see Chester as home to their team, the Philadelphia Union, and celebrate the new stadium as proof of the growing popularity of the sport in the United States. Chester’s revival appears on track—as long as all eyes remain focused on the new developments along the waterfront and are not diverted by the crumbling neighborhoods nearby.

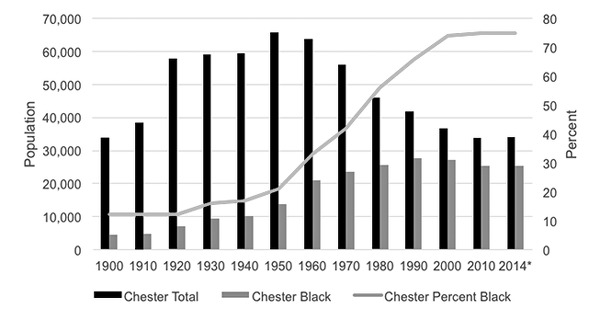

The casino and the stadium sit in striking visual and social contrast to the rest of Chester, the small city left behind long ago—the city people travel through at high speeds, the city people ignore, or, as they have for decades, consciously avoid. Among the residential streets and in the downtown core, the consequences of decades of political neglect and economic decline are readily apparent. The city’s landscape is peppered with dilapidated but still occupied row houses, countless empty storefronts, and abandoned lots, with an occasional corner grocery and a small number of bars, taverns, and liquor stores. Of the thirty-six thousand people who live in Chester, 80 percent of whom are black, more than a third are “officially” poor, and a quarter over the age of twenty-five have earned less than a high school diploma. Chester consistently ranks high in official federal and state statistics for street gang activity, assaults and homicides, poorly performing schools, long-term unemployment, and sagging community health levels. In February 2015 Neighborhood Scout, an Internet website that provides crime, school, and real estate data for cities and neighborhoods across the United States, ranked Chester the second most dangerous city in the country.1 Chester is Pennsylvania’s poorest city and is located in the state’s wealthiest county.

For most of Chester’s poor, black residents, the leisure enclave rising along the waterfront is the source of many changes but few benefits to their daily lives. The casino and the stadium employ residents but primarily in low-wage service sector jobs—as janitors, security guards, and restaurant staff. For most, the waterfront is an off-limits enclave meant for suburbanites to gamble, see a soccer game, or attend a corporate-sponsored event. A casino and a Major League Soccer stadium can hardly be considered meaningful urban revitalization for a disadvantaged city with crumbling infrastructure and no supermarket, “big box” store, or thriving small business district. As a twenty-seven-year-old resident told a New York Times reporter covering the city’s revival, “We’ve got a casino, a prison and now a stadium but we don’t have a recreation center or even a McDonald’s in this city.”2 If anything, the waterfront has further confined its residents to the inner city, as past uses of the waterfront—from hanging out and meeting up to barbequing and fishing—are now unwelcome or simply prohibited. Today, high-tech surveillance and new crime control initiatives police the public spaces along the waterfront and increasingly, the city proper. For young people, particularly young black males, ordinary behaviors such as hanging out or congregating on a street corner, have become coded as suspicious and potentially threatening to the success of the city’s regeneration. In the politics of urban development, the residents of Chester themselves seem to stand in the way of the city’s reinvention as a destination for middle-class suburbanites.

Even though Chester’s black community feels left behind, further marginalized, and increasingly scrutinized, city officials and developers are quick to contend otherwise. They argue that the new Chester promises residential, work, and entertainment spaces open and accessible to all—provided they can afford to participate. They claim waterfront redevelopment benefits the entire city despite the fact that it provides few tangible resources to tackle long-standing social problems or to meet needs prioritized by the community. Infused with a language that celebrates the allure of the “free market” and economic capital, the city’s future is shaped by leisure activities, spectacles, and consumption, as evidenced by its “rediscovery” by tourists, visitors, and eventually residents from varied, albeit mostly white middle-class, backgrounds. The new Chester is a more socially inclusive city than the Chester of the past. To claim otherwise is to remain stuck in outdated and failed ideas of urban renewal in which institutional racism, bias, and discrimination were recognized among the main causes of urban poverty. Chester has moved beyond that, embracing a post-racial, nonpolitics of urban development, where the winner is “the city” and the losers are unfortunate individuals—but not entire communities.

This image of Chester as a city embracing all things entrepreneurial and welcoming diversity helps legitimize the current progrowth model of urban development politics in which most of the city’s residents are left out in the cold. Race—or more precisely in this case the denial of the salience of race and racism—serves as a useful strategy to normalize a city’s ambitions for economic development at the expense of meaningful community development. The ideology of racial color blindness sorts out and makes sense of the apparent disconnect between the everyday realities of the inner city and the upscale ambitions of the adjacent waterfront.

This book focuses on how local political leaders, developers, the real estate industry, and other powerful stakeholders intentionally and strategically employ the ideologies and rhetoric of race to facilitate and legitimize certain types of urban development and to exclude others. In the current progrowth politics of urban development, the ideology of color blindness comprises a race strategy that facilitates exclusionary urban redevelopment and, in turn, marks a clear distinction between economic and community development.3 Chester’s redevelopment is meant to attract middle-class, suburban consumers. Redevelopment is not meant to address the collective needs of poor black residents of a city reeling from decades of racial segregation and deindustrialization. This exclusion of community needs is enabled by the ideology of color blindness, which is politically useful because it rejects the contemporary relevance of systematic racism and explains urban inequality as the product of “nonracial dynamics.”4 The social problems of urban poverty, inferior housing, chronic unemployment, and deficient education are largely attributable to individuals or their collective, cultural deficiencies but not to institutional or systemic racism. The race strategy of color blindness provides ideological cover, however thin, for urban development policies and practices that exclude and further marginalize the minority poor without the appearance of doing so.

Color-blind racial ideology is strategic to Chester’s progrowth politics. The economic and social problems of the inner city are seen as the remaining vestiges of inefficient or hindered market forces or the private and unfortunate consequences of the choices and behaviors of residents themselves. The city’s poor black residents are less a community or constituency than a collection of individuals who either comply with the goals of contemporary urban development—as consumers, low-wage workers in the waterfront facilities, or simply bystanders (who neither participate nor stand in the way of revitalization)—or they are obstacles and regarded as potential security threats. The minority inner city, then, is redefined not as a place replete with systematic discrimination and exclusion but as a post-racial realm hamstrung by the deficiencies of individual self-sufficiency, responsibility for one’s social welfare, and participation in the market economy. The reimagined inner city as a space devoid of problems caused by racism and racial discrimination is not epiphenomenal to contemporary urban development, it is at its core. And Chester, like many other American cities, is currently reimagined in this very way. As told in this book, Chester’s past and present are consistently shaped and defined by the different uses of race as a strategy in the local politics of urban development.

Employing Race Strategies in Urban Change

The use of color blindness to shore up the stark disconnect between Chester’s waterfront economic development and the minority city’s community underdevelopment is but the most recent occurrence of a long-established pattern of employing race in the politics of urban development. Drawing on the history of Chester and its suburbs, this book examines how the systematic and intentional employment of race shapes urban and metropolitan spaces in older, decline belt cities of the Northeast and Midwest. Race does not merely serve as an ideological setting or context in which urban development unfolds. Instead, the rhetoric and discourses about race and racism are intentionally fused to the wide range of local political processes linked to city development—from the early formation of the urban ghetto, to suburbanization and inner city decline, to more recent attempts at revitalization. Race strategies, then, are formative in the sense that rhetoric, representations, and discourses of race are manipulated and employed by key power holders to facilitate and legitimize certain kinds of urban change over others.5

As the chapters in this book recount, the use of race strategies is not exceptional but forms a normalized part of doing business in the spatial development of cities and suburbs over the past century. Repeatedly, race strategies have proven to be a useful and efficient means for local political leaders and private actors to push through, accelerate, and profit from profound changes in the urban-suburban landscape. They remain effective largely because race—or more precisely, fictions about race—consistently resonate in the public consciousness, even as their meanings continue to change over time. As W. E. B. Du Bois warned in 1903, “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.” But like most social problems, the color line in the United States has transformed in ways both intended and unforeseen, stemming from popular collective action, political economic changes, and shifts in cultural and ideological frames. Throughout the long century, issues of race—fictitious and otherwise—have continued to resonate powerfully in the media, on college campuses, in national politics, and in the local politics of space.

In the United States, the history of urban development reveals the enduring significance of race. At the city-suburb level, racial divisions are visible in most aspects of contemporary society, including policing and criminal justice, education, health care, access to financial capital, and social service provision. Progress has been made in narrowing certain dimensions of the racial divide, as evidenced by limited and uneven declines in racial segregation and in the public intolerance of blatant racial prejudice.6 However, whether measurable racial segregation is slowly disappearing or is sustained in new, elusive ways rests on a literal, demographic interpretation of the racial divide. Such a view neglects the ideologies and rhetoric of race and racism, another dimension of the racial divide and one that can be wielded or employed strategically to shape metropolitan development. While the meanings and ideologies of race and the black-white divide have been and continue to be redefined, they nonetheless are consistently used to influence the direction, limits and possibilities of urban change.

The significance of race to the way cities are shaped and formed is not easily severed from the importance of social class inequalities. But in the politics of urban development, race is symbolically and discursively separated from class; issues of race are employed in their own right as a strategic means for local elites and governments to shape and advance the direction of metropolitan change. Class inequalities shape urban restructuring, from suburbanization to abandonment to revitalization. Yet urban restructuring is imagined, worked out, legitimated, and reconciled in an urban politics that consistently relies on the wielding and, more often than not, cynical manipulation of race and the racial divide. This book’s focus on the strategic quality of race is not to deny or downplay the significance of other dimensions of race and racism to urban inequalities but rather to argue the opposite: that race so clearly, consistently, and problematically resonates in American popular culture that it is a highly useful sociocultural prism through which the politics of urban development is represented, understood, and acted on. Urban inequality and division, Georg Simmel reminds us, “is not a spatial fact with sociological consequences, but a sociological fact that forms itself spatially.”7 The utility of race in the politics of urban development will not disappear as long as the fiction of race remains a powerful (and useful) ideological basis for the way Americans perceive and react to their cities and suburbs.

The use of race in the politics of urban development has lasting chilling effects on minority communities. The utility of race strategies relies on the distortion and manipulation of race, racial groups, and purported racial behaviors. The purpose of this book is not to critique the fictive content of racial rhetoric and discourses per se but to trace their utility as a strategic means to legitimize and push through certain forms of urban change over others. Nonetheless, the stories recounted in this book document how urban politics draws from the rhetoric, ideologies, and fictions of race in an attempt to silence or speak authoritatively on behalf of “a black community” and to render invisible the actual diversity of those who reside in the city. Too often, the “noise” of urban politics drowns out the voices of various grassroots proponents of community-focused development. As the following chapters show, race strategies have often thwarted the efforts of community-based networks to shape a more progressive future for the city at different points in its history. But it would be a mistake to assume that the often-stigmatizing discourses that constitute race strategies position black residents solely as “victims” or passive agents of larger, more powerful forces. As the details in the following chapters also reveal, Chester’s black residents organized and promoted their own vision of a livable city at various points and accomplished much in ways both spectacular and mundane, given the context of larger political and economic circumstances. Grassroots social movements, activist churches, local civil rights associations, block associations, and community organizations consistently fought for their constituents against the narrow agenda of powerful stakeholders in city development. The wielding (and manipulation) of race in the politics of urban development does not eliminate community populism and everyday meaningful practices on the ground in black communities. Indeed, such practices and the ordinary lives of most residents may be seen as quiet resistance to the fiction of race put forth and used by those in power.

Outline of the Book

The following five chapters examine the different uses of race strategies in the politics of urban development. The chapters are arranged chronologically from the early 1900s to the present but the book in its entirety does not present a comprehensive history of Chester. Instead, each chapter features vignettes that center around how different racial strategies are intentionally linked to changes in urban space, from racial segregation and the emergence of a black ghetto to inner city disinvestment and the more recent revitalization of the waterfront. The chapters illustrate the strategic choices available to actors at key moments, the articulation of their interests through the language of race and racism, and how opportunities to mend the racial divisions were rarely explored and often exploited.

Chapter 2, “The Racial Divide in the Making of Chester,” examines how race first emerged as a strategy in the politics of city building in early twentieth-century Chester. As a consequence of the city’s 1917 race riot, black and white divisions defined the spatial reorganization of the city. Segregation hardened, providing the basis for white privileges in the urban environment but not without ensuring a level of security and stability for the black community with long-lasting consequences for racial integration efforts. The chapter also tells the story of race and industrial employment and how race was used in the workplace politics of industrial unionization in the 1930s and 1940s. As the chapter shows, race emerged as a complex yet reliable political flash point in the social and spatial organization of Chester. Race became the ordering mechanism of urban change and its employment as a strategy would continue to shape the politics of city and suburban development for decades to come.

Chapter 3, “How to Make a Ghetto,” examines how strategically employing racist fears became embedded and institutionalized in the postwar politics of urban and suburban segregation. During the 1950s, political leaders used the threat of integration to goad the public commitment of local whites to uphold and reproduce the city’s black-white divide. In response to the growing black ghetto whites “hunkered down,” taking the lead and joining forces with political and economic institutions to prevent blacks from encroaching into white neighborhoods—and eventually, suburbs. Stoking racial fears would play into the emerging interests of politicians, developers, and institutions in the promise (and profits) of the surrounding suburbs. As the chapter shows, the threat of an undoing of the racial order encouraged white flight from the city. The suburbs in turn became the convenient “spatial fix” to the pressures of racial integration. While racial prejudice and bias reflected the dominant racial ideology of white privilege at the time, chapter 3 explains how race-baiting became normalized in the politics of metropolitan expansion in the 1950s. The officially sanctioned use of racial animus and fears clearly points toward the intentionality, not the inevitability, of suburban exclusion.

Chapter 4 examines the curious circumstances surrounding Chester’s part in the civil rights activism of the 1960s. Chester was a hotbed of demonstrations, protests, and boycotts to end racial segregation, earning the city the reputation of being the “Birmingham of the North.”8 But here the familiar story of 1960s black activism is anything but straightforward, as white political elites embarked on a duplicitous strategy of defending and disrupting the city’s long-standing racial order. Chapter 4 picks up on the racial fears of whites that were exploited and strategically employed to the point where local political leaders were directly implicated in fomenting civil unrest. After months of demonstrations and unrest in the streets of Chester, the politics of suburban development fully exploited white anxiety over the city’s collapsing racial status quo. As chapter 4 reveals, local political leaders added fuel to the smoldering racial divisions and readily profited from the consequences of doing so. By 1970 the outward movement of mostly white families and small businesses and the decline in industrial employment left Chester’s remaining, largely black population concentrated and isolated in an aging core with few economic options.

Chapter 5, “Five Square Miles of Hell,” tells the snaking story of the city’s downturn from the late 1960s to the mid-1990s. The chapter focuses on the way political and private sector elites manipulated and used the racial ideologies and rhetoric of the black underclass to drain the city’s coffers and the remaining residents’ meager resources. Race became the strategic means to create and reproduce a sophisticated parasitic politics of urban underdevelopment. The relatively small gains in economic and housing conditions for the city’s black majority (compelled by Pennsylvania and the federal government’s War on Poverty) were quickly squandered by vast municipal corruption that implicated white elites and emerging black leaders and condemned large tracts of the city to economic despair and social isolation. While the majority of the city’s residents were subject to persistent crime, poverty, and unemployment, city leaders and private investors cannibalized the industrial waterfront, transforming it into one of the major toxic waste zones on the East Coast. Chapter 5 speaks to the strategic political decision to “chase smokestacks” and use race to win over the cooperation of corporations, regulatory agencies, and briefly the people of Chester.

Chapter 6, “Welcome to the ‘Post-Racial’ Black City,” returns to contemporary development along Chester’s waterfront. It sets out to explain the strategic relevance of race to making sense of and justifying the physical and symbolic disconnect between the city’s minority community and the new entertainment district rising along the Delaware River. The chapter lays out the political economy of the waterfront development and demonstrates how color-blind racial ideology legitimizes the exclusion of the vast majority of the city’s residents. The chapter concludes with a discussion of what may be learned from the persistent association of race and development as presented in the book. It calls for greater community stakeholder involvement that would generate the kind of urban development that is socially advantageous without furthering racial exclusion. This would require implementation of more inclusive decision-making processes. Instead of excluding the current inhabitants and further downplaying community ties to the future of urban development to attract capital and new residents, strategies should be developed that focus on revitalizing community in meaningful ways.

Racializing How Urban Spaces Are Unevenly Produced

In the 2015 inaugural edition of the journal, Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, the race scholar Eduardo Bonilla-Silva wrote, “Sociologists have done a pretty decent job documenting and theorizing how class . . . and gender . . . shape space and organizations. But we are behind in theorizing how race does the same.”9 The purpose of this book is to respond to this call and to interject the strategic dimensions of race into our existing understanding of the political economy of urban development. Urban sociologists and geographers have long emphasized the structural effects of racially discriminatory governmental policies on metropolitan areas and have provided detailed analyses of the effects of institutional discrimination on concentrated poverty.10 The origin and persistence of racial segregation is clearly connected to the broader political economy of capitalism. In particular, racial discrimination has been directly tied to the workings of real estate investment and development and federal housing programs and policies.11 But established theories of urban political economy tend to emphasize the relevance of capital flows and social class divisions at the expense of other equally important factors, including the discourses and rhetoric of race. To this end, this book should be read alongside important work on political economy to develop a broader understanding of urban development.

This book’s emphasis on the politics of development, in particular the agency and intentionality behind the strategic use of race, is a necessary complement to explanations of American urban development in which structural elements of race and class are highlighted. Much of the short history of the post–World War II U.S. city is neatly condensed in a grand narrative of suburbanization, white flight, deindustrialization, and gentrification. The legacy of post–World War II discriminatory policies and actions, including governmental housing and transportation policies, institutional lending practices, and the private behaviors of realtors and home owners, is today’s racial segregation and exclusion (and the subsequent costs to the health, safety, and education of minority communities). For those who emphasize the successes of the civil rights era in diminishing racial discrimination, the continued existence of inner city black ghettos is but an unfortunate by-product of revitalization efforts or simply the failure of recent urban redevelopment to deliver on its promises. There is nothing inherently wrong with these broad historical brushstrokes except that they have become convenient shorthand for otherwise complex events and processes that transpired in real time on the ground (as the chapters in this book attempt to show). Agency and intentionality are too often flattened in structural accounts of urban development. This book tries to correct that.

By focusing on a single city, this book demonstrates how race is strategically linked to the the local politics of urban development. The intentional use of vignettes (and not a complete social history) avoids a familiar case study retelling of twentieth-century urban rise and decline. That narrative, which incorporates the stories of metropolitan growth, deindustrialization, suburbanization, and gentrification and whose broad contours are indisputably correct, has been told repeatedly, so much so that a convincing inevitability can be read into the past of older American cities. Chester’s story clearly ties in with the urban rise-and-decline narrative, but this book tries to avoid a standard recounting and instead reveals the sometimes unexpected and always complex interplay of context, racial categories, constraints, decisions, and choices regarding urban change in different time periods.

The ideology of race neutrality notwithstanding, racial divisions continue to shape everyday life in ordinary, spectacular, unexpected, and often tragic ways. Strategically invoking the rhetoric and ideology of race and racism is a cynical politics of manipulation, as the stories presented in this book attest. The deliberate stirring of collective anxieties, fears, and animosity through the use of racial stereotypes, racist imagery, and racially coded language is an act of power that undermines the best intentions of individuals and organizations working to solve social problems at the local level and working to create more livable cities. The use of discourses of the racial divide by political leaders and developers to further their own agendas drowns out and threatens to silence the progressive voices of grassroots political and civic institutions eager to rebuild their communities. Although the chapters that follow concentrate on the cynical use of race by those with the power and means to do otherwise, the intended objective of this book is not a pessimistic one. Pointing out the pragmatic uses of race in the politics of urban development is a troubling but necessary and modest step in the ongoing efforts to end the isolation of individuals and organizations seeking to improve their cities.