2

The Racial Divide in the Making of Chester

When World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, Chester, Pennsylvania, was “a sleepy, provincial little city through which rushed, without stopping, the more important express trains to Baltimore and Washington.”1 Three years later and as a result of a ramped up war economy, Chester was a full-fledged industrial boomtown. Between 1910 and 1920 the city’s population jumped from thirty-eight thousand to fifty-eight thousand due to an influx of southern and eastern European immigrants and southern U.S. blacks. Waterfront factories making locomotives, ships, and machine parts hummed around the clock, and new stores, hotels, restaurants, and movie houses sprang up across downtown. Worker housing was woefully overcrowded and in short supply, and an antiquated infrastructure of sewers, roads, and transport groaned under the weight of increasing commerce and activity. Like most boomtowns, Chester was unprepared for the dramatic social changes that accompanied rapid growth and instigated class, ethnic, and racial divisions and tensions. And like many industrializing cities in the early twentieth century, those tensions erupted along racial lines. When a race riot broke out in the city in July 1917, Chester joined ranks with seventeen other cities that suffered racial unrest between 1915 and 1919.2 And as in those other cities, the separation of blacks and whites in Chester’s neighborhoods and workplaces hardened.

Racial segregation in northern industrial cities issued from the racial antipathy of whites toward blacks. But the hardening of segregation also reflected the fierce pragmatism of early twentieth-century machine politics bent on preserving control of the ballot box and the perks of local office. The issue of race was not of tertiary concern to political leaders and ordinary citizens grappling with the challenges of fast-paced growth. Indeed, race became the fulcrum for both assigning blame for the social ills that accompanied urban growth and for the consolidation of municipal power based on neighborhood politics. In the years following the 1917 riot, issues of racial contact in public places, in neighborhoods, and in the workplace remained front and center and came to define local politics. After 1917 the preoccupation with race inflected the geography of residence and employment, and the manipulation of racial tensions became a useful means for both politicians and industrialists to push through social change (or prevent it). Despite the dramatic changes brought about by two wars and an economic depression in the first half of the twentieth century, the fixation with race did not wane. Indeed, it intensified and set the strategic tone for the subsequent development of the city and its suburbs.

Race and Small-Town Life

Chester’s backwater status on the eve of World War I had been centuries in the making. Pennsylvania’s oldest city, Chester was first settled by Swedes and Finns as Upland in the 1640s. English settlers arrived seven years later. William Penn spent 1682 there with the intention of making Chester the colonial capital. A land dispute forced Penn to relocate up the Delaware River to present-day Philadelphia, leaving Chester to spend nearly two centuries as “an insignificant provincial hamlet.”3 Chester was the administrative center for county politics, serving as county seat in the first half of the nineteenth century. A borough until 1866, it was incorporated as a Pennsylvania third-class city in 1889 and elected a Quaker as its first mayor. The region’s wealthy landowners and business families built stately homes on the city’s north side, while the waterfront housed a few lumber mills and small shipbuilding companies.

Industry slowly began to exploit Chester’s riverfront location around the time of the Civil War. A number of textile factories, including the massive Crozer mills, joined the city’s oldest industrial firm, American Dyewood, which manufactured dyes for silk, wool, furs, and leather. Access to the Delaware River attracted the shipbuilding business in the 1850s. The expansion of industry and immigration, fast paced in other, larger cities in the late nineteenth century, occurred slowly and modestly in Chester. In the last few decades of the century, steel casting firms set up shop, manufacturing castings used in shipbuilding, dredging, cement and rolling mills, and hydraulic presses. New banks, department stores, theaters, and restaurants gave rise to the city’s central business district. Between 1890 and 1900 Chester’s population grew from just over twenty thousand to thirty-four thousand. Chester’s leaders and its upstanding citizens may well have thought of their city as a more cosmopolitan version of a small town, but its reputation among outsiders had long centered on its notoriety as a freewheeling destination for vices such as drugs and alcohol, numbers rackets and gambling, and prostitution. Decades prior to the vast changes brought by World War I, Chester was widely known as Greater Philadelphia’s “saloon town.”

Overseeing and profiting from Chester’s hybrid mix of industry and vice was the city’s Republican political machine, which came to dominate local politics in 1875 and completed its political control over all of Delaware County by the start of World War II. Both the machine and its leadership are noteworthy for their longevity. John J. McClure took over as political boss from his father in 1907 and oversaw the machine’s operations until his death in 1965. With the exception of 1904–1906, machine politics ruled Chester continuously for nearly a century. A nonmachine mayor was not elected until 1992.

Like most turn-of-the-century political machines, the base of McClure’s power was liquor. The McClures first influenced and then controlled local- and county-level elected officials receptive to (and increasingly dependent on) the city’s liquor licensing and saloon trade through the family’s monopoly of wholesale liquor distribution. Chester and Delaware County’s patronage system was a quid pro quo between tavern and saloon owners and elected officials: judges issued liquor licenses, and in turn bar owners drummed up votes and provided beer and a free lunch to voters on Election Day. Over time the machine deepened its reach into the everyday lives of Chester residents, granting favors in exchange for votes and strongly influencing a whole range of opportunities from their jobs and promotions to where they were welcome to live and the quality of the schools their children attended. The McClure machine handpicked candidates for county, city council, mayoral, and school board elections. The spoils of his rising political and economic power gave John J. McClure access to seats on the boards of banks, industrial firms, and other social and business interests. With his high-profile reputation, he found ardent support among local large manufacturing concerns, small business owners, and the growing legions of industrial workers. From time to time antivice social reform candidates surfaced to battle county and municipal corruption and to unseat elected officials who openly participated in and benefited from the machine-sponsored vice trade. But such efforts at reform and law and order were short-lived and produced no lasting changes to McClure’s stranglehold on local politics. By the early 1900s McClure’s machine was firmly in control of the politics and economy of Chester.4

McClure perfected his loyalty and patronage system through a multilayered network of political operatives who reached down deeply and bestowed favors to individual households. McClure locked up the votes in the five most populous and poorest wards, appointing ward lieutenants who wielded minor power over everyday affairs in their precincts but deferred to the machine boss over matters of significance. The vast network of machine operatives took orders from a storefront at Third and Kerlin Streets in Chester’s South Ward known as “the Corner,” where high-level Republican Party officials rubbed shoulders with their precinct-level counterparts. From there McClure consolidated his power over the political geography of the city (and soon after, Delaware County).5 McClure also took advantage of the city’s racial geography, defined by stable, unchanging, and seemingly ordinary social and spatial divisions between blacks and whites. Because the machine extended its vote-generating and favor-granting apparatus to all neighborhoods regardless of race, McClure countered periodic challenges to party rule from white progressives by mobilizing working-class districts, both black and white. McClure also found race a reliable and strategic means to effectively cover his involvement in the machine’s lucrative side industries, including vice. In short, Chester’s somewhat unremarkable black-white divide was vital to the success of the machine, and McClure spent considerable time and energy on maintaining it.

Like many other small northern cities, Chester’s geography was a mix of white and black middle- and working-class neighborhoods of varied sizes whose boundaries changed imperceptibly over the decades. By 1900 Chester’s black community had been established for well over a century, and the black population of forty-four hundred fluctuated very little prior to World War I. Although small in comparison to cities such as nearby Philadelphia, the community’s economic and social lives flourished. A 1910 survey by the Pennsylvania Negro Business Directory lists six groceries, eight restaurants, two hotels, pool halls, barbershops, general contractors, cab operators, dressmaking shops, undertakers, and two black newspapers. There were nine black churches, with St. Daniel’s Methodist, Asbury African Methodist Episcopal (AME), Calvary Baptist, Bethany Baptist, and Murphy AME Churches claiming the largest congregations. The Elks, Grand Order of Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias, Masonic Lodge, and smaller fraternal orders, lodges, and social clubs recruited members from the working and middle classes. A neighborhood’s location, character, and amenities reflected the prevailing social class of its residents, defined by occupation, income, and social status. Black small business owners, schoolteachers, ministers, physicians, and lawyers lived in the West End, the residential blocks close to the central business district. Black laborers, janitors, domestics, and saloon operators lived in the crowded blocks of the Eighth and Ninth Wards close to the industrial waterfront. Others employed in the city’s thriving vice economy lived in Chester’s “red light” district, Bethel Court, along with poor newcomers trickling (and later flowing) in from the South. Although separated from white residences, blacks were not confined or strictly segregated within a single area of the city. Instead, the number of small black neighborhoods, whose boundaries were neither rigidly fixed nor policed, expanded or contracted by a block or two depending on industrial hiring booms and busts.6

Regardless of a black neighborhood’s location or the social class status of its residents, many of the everyday operations and the lives of those who lived there were overseen by a network of Republican political machine operatives or lieutenants. In addition to collecting protection fees and assuring voter turnout, McClure operatives mediated disputes among residents; raised bail money and legal fees for constituents in trouble; offered small sums of money, shelter, and other charitable resources to the needy; and supported local events, parades, and sports teams. Their activities and influence were not limited to the livelihoods of just the black working class. The machine controlled the limited professional occupational opportunities available to Chester’s black middle class. McClure himself handpicked candidates for the school board and controlled the hiring of schoolteachers, the foremost career path to the middle class. Faced with no viable alternatives, blacks supported McClure and consistently voted for machine candidates. More than a handful profited from the association and gladly carried out the machine’s bidding. As McClure intended, the machine held sway over the everyday lives of Chester’s blacks, whether they resided in Bethel Court or on a modest middle-class residential street. Owners of funeral parlors, pool halls, hotels, and pharmacies that catered to a black clientele owed fealty to the political machine in one form or another. Chester’s soft racial segregation was a normalized feature of everyday urban life, but what mattered was the political purpose that the racial divide served in assuring the dominance of the local political machine.

The network of black saloon keepers, shop owners, and hotel owners assured the necessary Republican votes on Election Days and the Republican machine in turn provided favors to locals ranging from jobs, school placements, legal assistance, and emergency aid. They were expected to faithfully contribute to campaigns and produce large election majorities for the machine—and they did. To the chagrin of Chester’s black residents, many of the very same political operatives who managed prostitution, gambling, and other vices on behalf of McClure played a hand in determining who obtained and maintained a black middle-class professional status. For the machine, the social (and to some degree physical) distance between the city’s white and black residents allowed for a politically expedient and profitable manipulation of appearances. Black operatives were the visible “front men” on display and seemingly in control of the everyday operations of saloons, brothels, gambling joints, and flophouses, leaving white political leaders to profit outside the public eye.

The selective incorporation of blacks, on whites’ terms, into machine politics was not unique to Chester. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, such incorporation was widespread in cities such as New Haven, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Baltimore, and New York.7 In most cases, this avenue of black entry into urban politics created the opening for autonomous black political leadership and organization commensurate with the waning influence of urban political machines. The power of Chester’s political machine remained uncontested well into the final decades of the twentieth century, however, short-circuiting the development of black political autonomy.

Race and the Rapid Growth of the City

Chester’s early twentieth-century racial compact proved functional to the local political machine, both maintaining the racial social and spatial status quo and solidifying the local power structure of the Republican Party. But Chester’s rapid growth in wartime industrial workers upended this racial arrangement. Preparations leading up to the U.S. entry into World War I transformed Chester into an industrial boomtown almost overnight. Blame for the subsequent strain on the small city’s resources coupled with increased patronage of its reputed vice district fell squarely on the shoulders of blacks, both newcomers and existing residents. The racial tensions that violently erupted in the summer of 1917 were not unique to Chester but reflected rising hostility among whites in many northern cities toward the influx of southern black workers. But the ease with which Chester’s whites readily blamed blacks for social problems, including machine-run vice, speaks to the power of McClure’s manipulation of racial divisions.

War demands for munitions and supplies brought a quick expansion of shipbuilding docks, assembly plants, and heavy industry along the waterfront and unprecedented growth in industrial employment. Only two years after it opened in 1916, the Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company (also known as Sun Ship) became the city’s largest employer with over sixteen thousand workers manufacturing ships and repairing engines and machine parts. Other giants in Chester’s industrial history—Baldwin Locomotive Works, Chester (later Scott) Paper, Westinghouse, and Sun Oil in nearby Marcus Hook—were founded during this time of extraordinary expansion. Tens of thousands of workers poured into Chester daily. Fifty-six local trains shuttled commuters back and forth from factories to their homes in Philadelphia, Wilmington, and adjacent small towns. But the most notable change was the staggering increase in new residents. Estimates at the time put the population growth rate at 100 percent, doubling the city’s size from forty thousand in 1914 to eighty thousand in 1918.8 Immigrants from Italy, Poland, Lithuania, and other parts of eastern Europe flooded the city, carving out ethnic niches cheek by jowl in existing neighborhoods and suddenly infusing the small city with a cosmopolitan flair.9

Business and political leaders welcomed growth and the fortunes it brought. But the city’s long-term residents and civic leaders viewed rapid growth as mostly negative, as Chester’s small-town feel was soon vanquished by industrial growth and urban congestion. Within eighteen months, the city’s population trebled with the influx of immigrants and southern blacks. Manufacturing employment reached record levels; housing was woefully overcrowded and in short supply; and an antiquated infrastructure of sewers, roads, and transport groaned under the weight of increasing commerce and activity. Sidewalks were overcome by the onslaught of commuters, newcomers, and strangers, and trolley lines teemed with a mix of shipbuilders, welders, factory workers, businesspeople, and mothers with their children. New pupils crammed schoolrooms. The city’s housing supply, meanwhile, grew by only thirteen hundred units. New arrivals looking for employment found limited housing choices. Hastily erected work camps that popped up adjacent to factories were filthy and overpopulated. Many single-family homes became makeshift rooming houses with closets and bed space rented to mostly male boarders. Like all boomtowns, Chester was unprepared for the dramatic social changes that accompanied speedy growth. But among the class, ethnic, and racial divisions fueled by the city’s rapid change, racial divisions rose to the fore.

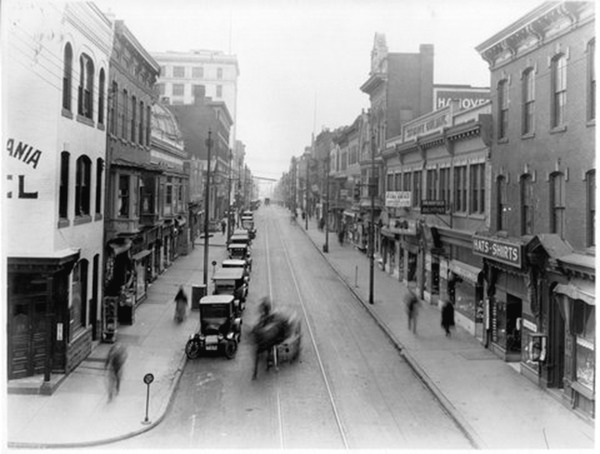

View of Market Street from the railroad, November 28, 1922. Reproduced by permission of the Delaware County Historical Society, Pa.

In 1910 Chester was home to six thousand blacks, who were roughly 15 percent of the city’s total population. At the peak of the war boom, the city’s black population was over twenty thousand, or 25 percent of the total.10 In 1916 and especially in the spring of 1917 thousands of black workers (mostly young males) poured into the Philadelphia region, including Chester, as part of the Great Migration to the North during World War I.11 New arrivals gravitated to the city’s black neighborhoods but found the established working- and middle-class districts unwilling or unable to accommodate such large numbers. Bethel Court, already teeming with Chester’s poorest blacks, provided the main option; others included racially segregated work camps set up by the larger waterfront employers. The camps housed over two thousand black workers. Thousands found residence as lodgers in rooming houses and private homes, as tenants in converted garages and warehouses in the industrial areas, or as squatters in abandoned buildings.12

Chester’s uneasiness, frustration, and uncertainty with rapid growth and congestion found a single, common focus among whites in general and the white middle class in particular. They placed the blame for a host of social ills squarely on the influx of black workers from the South and the subsequent unraveling of the city’s racial geography. Industry’s recruitment and hiring of black migrants into the local labor market fueled racial antagonism in Chester, as it did in many other industrial cities.13 Factory owners certainly welcomed the arrival of new workers, be they blacks from the South or foreign-born whites. Although jobs were plentiful thanks to the wartime economy, most working-class whites were outright hostile to the rising numbers of blacks in the workplace. Blacks, who had once been assigned to menial tasks in most industries, were for the first time working alongside white workers. Additionally, Chester’s white workers were well aware of tensions over the employment of black workers in cities elsewhere in the North and in the Midwest.

Labor’s conflict with industrial management led to a series of well-publicized strikes and work stoppages in which the hiring of blacks was seen as threatening to union gains. Black workers were collectively branded as would-be strikebreakers. The steel and meatpacking industries, for example, hired black workers to break highly publicized strikes in 1892, 1894, and 1904, fueling the racial animosity of white union workers across the country. Closer to home, labor riots broke out at a sugar refinery in nearby South Philadelphia when the management hired black workers to replace unionized strikers in March 1917. Reports of black workers hired as strikebreakers in Chicago, East Saint Louis, and other cities galvanized more far-reaching negative sentiments toward blacks among organized white labor. In the days following the race riot in Saint Louis in early July 1917, the local press drew parallels between the circumstances that led to violence in that city and those festering in Chester.

While the threat to labor mattered to many locals, white middle- and working-class anger over the influx of southern blacks crystallized around the proliferation of vice, the perceived collapse in civic order, and the spike in street and property crimes that accompanied the city’s rapid growth. With the rise in its economic fortunes, Chester’s notoriety as a city “where anything goes” was more conspicuous than ever, rankling social reformers, the local press, and middle-class citizens alike. As industry along its waterfront grew, so too did the number of taverns, beer joints, pool halls, brothels, hotels, and flophouses. By 1914 there were more saloons than police officers in Chester, or roughly 1 saloon per every 987 citizens.14 In 1917 the regional popularity of Bethel Court exploded when army and navy officials banned enlisted men stationed in Philadelphia from frequenting that city’s local brothels and similar “resorts.” Commuter trains and buses shuttled military and civilian patrons to and from Chester day and night. More patrons brought more drunken behavior, noise and commotion, and pickpocketing and similar petty crimes to Bethel Court—all conducted with apparent impunity.15

Whites attributed the surge in public drunkenness and the openness of prostitution and petty street crimes directly to the rising presence of working-age black males in the city. Like their white counterparts, many black migrants surely frequented Bethel Court. Unlike whites, however, many were simply lodgers relegated to the dilapidated rooming houses and second-story lodgings above the brothels, saloons, and gambling dens. Bethel Court had long been the focal point of repeated social reform campaigns and the public scorn of both middle-class whites and established black families. As McClure’s front men, however, blacks appeared to Chester whites to be responsible for the evils of the city’s chief vice district. The machine capitalized on this, paying lip service to social reform campaigns while lining its pockets with protection fees and kickbacks and the profits from liquor and beer sales. Hiding safely behind the cloak of black operators, the machine profited from Bethel Court’s saloons, brothels, gambling joints, flophouses, and rooming houses that catered to low-skilled laborers, the itinerant, and the poor. For Chester’s whites and local newspaper editors, however, blacks were “customers,” not residents. Bethel Court and all its immoral, criminal, and scandalous affairs were perceived as “a distinctly black problem.”16

Cover of September 1926 edition of Chester, a monthly industrial newsletter. Vol. 1, no. 3. Reproduced by permission of the Delaware County Historical Society, Pa.

The vast increase in workers also increased the likelihood of mundane public interactions between whites and blacks. Whites, for the most part, found this new development disconcerting. Their view of poor, mostly young, male southern blacks tested their racial assumptions formed from years of predictable interactions between middle- and working-class whites and the stable working-class and West End middle-class blacks. Charges of “black incivility” abounded in conversations and increasingly in print in local newspapers. Impolite behavior on a streetcar, for example, blossomed into a panic of black insolence and the deliberate intimidation of whites. Tales of belligerent blacks routinely accosting whites on public sidewalks circulated in the city’s white barbershops, beauty salons, shops, and restaurants. Newspaper coverage further racialized the social problems brought about by wartime expansion, adding fuel to racial tensions. In the spring and early summer of 1917 the Chester Times featured several stories about black perpetrators and white victims, ranging from minor affronts on streetcars to purported kidnappings and late night break-ins. Interview quotes from whites spoke of threats by aggressive black men to the public well-being and the moral and physical safety of white women especially. By July 1917 newspaper editorials and public discourse among whites gelled into a seamless rant in which black newcomers were potential scab laborers, disrespectful and threatening toward whites, immoral and indecent, prone to illegal behavior, and allowed to commit crimes with impunity. Discontent carried over into the blame whites placed on municipal leaders who failed to control the situation.

The highly charged atmosphere culminated in a deadly four-day race riot. Late in the night on July 24, 1917, a young black man named Arthur Thomas, his female companion, and another black couple walked through a predominantly white neighborhood on the city’s West End as they made their way home from an evening at a summer carnival. Thomas exchanged words with a white man named William McKinney. Words soon turned to fisticuffs, and McKinney was stabbed repeatedly in the ensuing scuffle and died shortly thereafter. News of the “cold-blooded murder” of a white man by a “black thug” spread throughout the city, and within an hour hundreds of whites milled about the scene of the stabbing demanding retribution. Thomas and his three companions were arrested early the next morning, but by day’s end only Thomas remained in custody, the others having arranged bail. That evening an enraged mob of whites marauded through the streets of Chester’s black neighborhoods, touching off violent street battles that continued for four days. The level of brutality was alarming, as newspaper accounts printed in the riot’s aftermath clearly indicate: the torching of row houses with their black occupants trapped inside, hand-to-hand combat in the city’s West End involving several hundred whites and blacks armed with knives and sticks, block-by-block gun battles, random beatings of unarmed blacks and sympathetic whites, and indiscriminate thrashings of black rail and trolley passengers. The Chester Times referred to the July 26 rampage as “a night of terror in the city.” Early in the mayhem, Chester’s mayor called forth additional state and local police officers, a mounted patrol, and national guardsmen to restore order, but by July 30 seven people had been killed, twenty-eight had suffered gunshot wounds, and hundreds had been treated at a hospital or were still hospitalized.17

The Hardening of the Racial Divide

In the days immediately following the riot, Chester’s political machine kicked in with its usual efficiency to facilitate a return to normalcy. After their bail was posted by a black machine lieutenant who ran a saloon in Bethel Court, one of McClure’s handpicked magistrates had released Thomas’s three companions from jail. But McClure underestimated the rage of his white political opposition, including the editors at the Chester Times. The paper featured several stories about the Republican Party’s ties to the city’s vice district and its deep connections in the black community. Unsurprisingly, the efforts to place responsibility for the unrest on the machine did little to diminish the blame the public accorded to Chester’s black residents, long-term and recent. Reporting indicated that a few weeks prior to the July riot, the same magistrate had released two black males arrested for accosting a white girl in a city park. Their bail had been posted by the same Bethel Court operative. The Chester Times published stories and editorials claiming that local police and courts officially tolerated Bethel Court’s rising lawlessness as part of the quid pro quo with machine operatives who managed saloons. Vocal critics of the machine held municipal politicians culpable for the riot and for abetting black lawlessness in exchange for votes. An editorial in a Philadelphia newspaper put Chester’s Republican Party at the center of blame:

These riots are traceable directly to the system of gang politics which has given Chester an unenviable notoriety. . . . The flaming up of the mob spirit is due to the fact that machine politicians have corrupted and demoralized a large part of the negro element, giving to criminals protection in return for political service. The result is that negro lawbreakers have committed almost endless acts of crime against whites and against the public peace with virtual impunity, and have become defiant of all restraint. It was because of frequent demonstrations that the processes of justice against negro offenders had been paralyzed by political influence that there was created a sentiment for lawless vengeance. . . . Intelligent citizens were aware that the minor judiciary was but an annex of the political machine. . . . This was the real inspiration of the “race riots.” There was prevalent among the whites a firm belief that negro criminals would not be brought to justice because they delivered political support to the machine.18

Within weeks of the riot, the mayor ordered the police to prohibit the sale of alcohol to military personnel visiting Bethel Court. The magistrate who had set low bail amounts for black offenders was dismissed from office. Progressive reformers were emboldened by the public outcry and challenged machine-picked candidates for local judgeships and city council seats in the fall elections. The vote count was close. Machine candidates prevailed but only because of the overwhelming turnout of black voters in their favor.19

The machine, which for decades had managed and manipulated the spaces and opportunities for racial interaction, appeared to have ignored the Chester white community’s mounting racial antipathy toward interacting with an increasing number of blacks. Instead, the machine chose the short-term promise of more money and votes from an increasing black population. With the riot of 1917, the machine’s exploitation of the racial division that it had long helped engineer seemed in danger of imploding. It did not. Despite the damning criticism of Chester’s politics, the social problems that accompanied fast-paced urbanization became effectively racialized. Blacks were the chief cause of the riot, albeit with the help of a political machine unwilling to impose law and order to uphold white privilege, thinly disguised in the aftermath of the riot as “community standards.” Racial division only hardened, offering new possibilities for the Republican machine to maintain its power among Chester’s whites and blacks.

Chester’s black population declined considerably as World War I ended and industries scaled back to prewar levels of employment. Nonetheless, white hostility toward the “encroachment” of blacks in public spaces, neighborhoods, schools, and workplaces not only lingered but toughened. The residential division of blacks and whites that had otherwise gone relatively unnoticed for decades was fully embraced by whites, who sought to formalize and expand it. Responding to this aversion were actors who held strong connections to the political machine and offered a set of spatial fixes to racial tensions amenable to whites. Local realtors, real estate boards, financial institutions, and title companies tendered restrictive housing covenants as a means for white property owners to solidify neighborhood boundaries. Used in existing city neighborhoods and in greater numbers of newer “first-ring” suburbs, covenants bound residents not to sell, lease, or otherwise convey their property to particular groups, including blacks. Covenants and other restrictive devices mollified whites’ reactionary need to hunker down, protect their communities, and exclude blacks from neighborhoods and, importantly, schools.

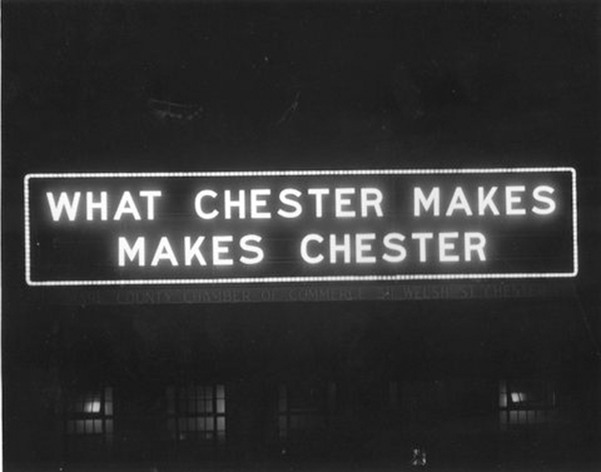

Neon sign atop Crosby St. substation of Philadelphia Electric Company, erected in 1926 and removed in 1973. Reproduced by permission of the Delaware County Historical Society, Pa.

On the other side of the racial divide, the local machine too offered a spatial fix in the form of segregation and the development of a black city within a city. In the immediate aftermath of the 1917 riot, the machine offered Chester’s black residents something progressive reformers could not: protection and security in the face of uncertainty and hostility from whites. After the riot hundreds of black residents fled the city and did not return. Most stayed and turned to their black ward leaders, who readily delivered the political machine’s promise of safekeeping. The promise was kept, garnering deeper loyalty to the Republican Party from a vulnerable population. The machine in turn imposed a harder form of racial segregation. Within a decade white and black ward leaders defined the boundaries of Chester’s black community in the city’s Ninth Ward in the West End, solidifying votes and loyalty to the machine and providing a machine-dominated infrastructure for economic sustainability and social organization of a black ghetto. West Third Street near the intersection with Flower Street became the main commercial boulevard, lined with beauty shops, restaurants, social clubs, bars, and restaurants catering exclusively to blacks or with segregated spaces in white-owned businesses, such as movie theaters. Class distinctions in black communities became more defined, with the social and economic statuses of the middle class tied ever more closely to the operation of the political machine.

McClure intensified his grip on key facets of black city life. He “kept a careful eye on virtually every facet of the Black community—schools, housing, law enforcement, recreation, plus certain jobs in industry. Moreover, if anything escaped his view, there were certain underlings to report to him.”20 Within the boundaries of the West End, social class mobility was directly dependent on individual or family connections to the political machine. In his study of black politics in Chester, Richard Harris describes the development of an oligarchy of ward lieutenants, religious ministers, and civil rights organizations that held sway over economic and social lives well into the 1950s. Machine lieutenants oversaw the hiring of all schoolteachers (a key middle-class occupation), and favoritism in factory positions and promotions was rampant. Harris claims that in 1945 two-thirds of Chester’s black schoolteachers were relatives or close friends of the community’s political families.21

Wielding a Race Strategy in Industrial Employment

The black and white division of residential space in Chester was mirrored in workplaces, particularly in the larger industrial concerns concentrated along the city’s waterfront. Employment was fully segregated by race, with black workers relegated to low-skill and menial labor positions, such as janitorial work. But the racial division of labor had further implications for the relationship between McClure’s Republican political machine and industrial leaders, especially the fiercely antiunion Pew family, owners of Sun Shipbuilding and, in nearby Marcus Hook, Sun Oil (later, Sunoco). As the city’s economy lurched from depression to yet another wartime boom, the machine’s favoritism and patronage systems remained pivotal in staffing the industrial labor force. The relationship between the political machine and big industry remained stable as long as each side benefited. Over the course of workers’ unionization efforts in the 1930s and wartime mass hiring in the 1940s, the machine-industry relationship turned adversarial, with Chester’s black workers routinely caught in the middle of a contested politics of labor.

In the early 1930s Chester’s political machine enjoyed the full support of local industrialists, among them the Pews and the operators of the city’s largest concerns—Baldwin Locomotive, Delaware River Steel, Atlantic Steel Castings, Delaware County National Bank, Westinghouse, and the Philadelphia Electric Company.22 McClure was a state senator the first half of the decade, assuring that the area’s industrial interests were voiced in the state’s capital and maintaining a probusiness climate in Chester and surrounding Delaware County. In Chester McClure benefited from corporate support for the Republican Party, which allowed the machine to adeptly fuse the politics of residence with those of the workplace. Before elections, the machine dialed up its voter turnout system, requiring patronage employees at Sun and other industries to recruit additional voters for polling day. As further evidence of the corporate-machine alliance, the Sun shipyard president John G. Pew called “mandatory meetings” of workers for machine-sponsored political rallies. Republican Party membership was a de facto prerequisite for employment at Sun.23

The value of long-standing ties between the city’s industrial leaders and its political machine became obvious when McClure lost his state senate seat and other machine politicians were swept from power in the 1936 election. Media coverage of the party leader’s ability to avoid imprisonment following his conviction on federal corruption and extortion charges fed the public outcry over his protected status. McClure had even survived a senate measure to force his resignation in 1935 only to lose in the election the following year. Even in Chester the machine’s victory was marginal, as only the majority black Ninth Ward supported the Republican ticket in each of its precincts. Defeated, McClure retreated to Florida. The 1936 elections proved equally disappointing for the Pew family’s interests. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who instituted price controls on various commodities as part of his economic recovery agenda, was reelected. Pennsylvania’s Democratic governor taxed large businesses to finance public relief programs.

The loss of county and state senate elections to Democrats worried the Pews and other corporate elites, who had benefited from the machine’s probusiness and low corporate tax policies. Faced with no acceptable local Republican leader to replace the retired McClure, Pew traveled to Florida to convince him to return as Delaware County’s Republican Party leader. Pew offered funding for future election campaigns and complete control over the hiring decisions for all positions at the Chester shipyard and the refinery in Marcus Hook. In effect, all jobs at Sun would become machine patronage positions. McClure accepted, and the ranks of loyal Republican voters swelled. In the 1937 elections Republicans swept back into local offices, and in 1938 the McClure machine experienced its strongest voter turnout ever.24

The McClure-Pew patronage employment deal began to unravel as a consequence of New Deal labor policies and the ongoing pressures for unionization at the shipyard. In an early effort to stave off unionizing, in 1922 Pew set up his own General Yard Committee for employee-management relations, which lasted until 1933. In 1934 the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipyard Workers of America (IUMSWA), a union active in shipyards along the East Coast, launched a campaign to organize Sun employees. Two years later 25 percent of Sun’s forty-two hundred employees were IUMSWA members. In December 1936 the IUMSWA called a strike, leading to a shutdown until non-IUMSWA employees “broke through the picket line and succeeded in entering the shipyard. In the ensuing riot many were injured, some seriously.”25 Pew refused to negotiate a settlement. Instead, he turned to McClure to help form an employer-sanctioned worker’s organization named the Sun Ship Employees Association (SSEA).26

McClure relied on loyal non-IUMSWA workers to break the strike, circulating petitions in support of the SSEA as the workers’ bargaining unit. Within two weeks, twenty-six hundred employees had signed the petitions, and Pew met with SSEA representatives and agreed to negotiate workers’ terms and conditions. The IUMSWA complained of unfair company practices to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and secured a consent election to determine which organization represented Sun workers. McClure designated one of his operatives at Sun to pressure employees to support the SSEA in the NLRB’s consent election in 1937.27 Of the ballots cast, 2,398 voted for the SSEA and 1,412 for the IUMSWA. After the election the SSEA appointed McClure’s operative “chief investigator of grievances,” permitting him to pre-interview applicants for yard positions to gauge their union sentiments and hinder promotion and advancement of pro-IUMSWA workers. McClure’s operatives formed a “strong-arm squad,” selecting “boys good with their fists” who could be called on if there was any trouble.28 For its part, Sun allowed SSEA activities and meetings to take place at the yard and on company time, and it set aside a room in a yard building for SSEA business. On December 31, 1937 Sun and the SSEA signed a labor conditions contract in which the SSEA was recognized as the exclusive representative of all workers employed at the shipyard.29

The IUMSWA continued to set its sights on Sun Ship, Chester’s largest employer, and its unaffiliated labor organization the SSEA. The IUMSWA’s efforts were emboldened in 1942—curiously enough by McClure, who worried that the powerful IUMSWA would eventually prevail and transfer thousands of Sun workers from the Republican ranks to the Democratic Party, the party more closely affiliated with the labor movement. In the NLRB proceedings in 1942, McClure’s operative who had helped form the SSEA testified against the Pews, providing a firsthand account of the company’s direct role in intimidating workers and approving strong-arm tactics to assure workers’ compliance. The historian John Morrison McLarnon III sums up the curious turnabout in the machine’s relationship with Sun:

There was no direct evidence that [the machine’s operative] got involved in the unionization of the shipyard in an attempt to save the labor vote for the Republican Party, no proof that he was sent into the shipyard as an agent of the machine. Nor was there any direct evidence that [he] testified against the Pews . . . at the behest of John McClure. On the other hand, the McClure lieutenant not only seemed to be at the center of most of the shipyard’s labor problems, but had gone out his way to “expose” the illegal labor practices of the Pews. Subsequently, McClure began paying him a regular weekly salary.30

As a result of the machine lieutenant’s damaging testimony, the NLRB found that Sun engaged in unfair labor practices and recommended that the IUMSWA replace the SSEA as the bargaining representative for Sun employees.31 The Pews ignored the ruling, prompting the NLRB to file suit in the Third Circuit Court of Appeals. The court ruled in favor of the Pews, citing inconsistencies in the testimony of NLRB witnesses. But the Pews rightly predicted that the NLRB would force a second consent vote pitting the IUMSWA against the company’s bargaining unit and would win. On June 30, 1943 the IUMSWA defeated the SSEA by a narrow margin.32 But before the Pews’ defeat the company tried another tactic: playing up racial tensions to advance an outright conflict among the ship workers.

In the midst of the labor union tumult, Sun Ship’s operations expanded. At the start of World War II the labor demands of local industry brought a flood of new workers, both black and white, to the city. The wartime labor force for industries along the waterfront soared to 100,000, in contrast with the highest prewar figure of 45,000. The Chester wartime boom was in full swing. Labor demands opened new areas of employment to black workers previously restricted to unskilled jobs.33 In addition to a labor shortage, the hiring of black workers was advanced in 1941 by Roosevelt’s Executive Order 8802, which prohibited government contractors, such as munitions manufacturers and navy shipbuilders, from employment discrimination based on race, color, or national origin.34 Prior to 1941 Chester’s industries abided by the unwritten but rigorously enforced “racial qualification for employment.” Baldwin Locomotive Works had restricted blacks to foundry work, but during the war the company expanded black employment throughout the company with the exception of the machine shop, “where employees threatened to quit if Negroes were employed.” A National Urban League report on black wartime employment found sizable proportions of blacks in several Chester industries, including Penn Steel Castings (36.3%), Crucible Steel Casting Company (50.0%), Chester Electric Steel Company (55.8%), and South Chester Tube Company (18.2%). Sun Shipbuilding employed the overall largest number of black workers, which at peak employment was 15,000 of a total workforce of 35,000.35 During World War II Sun became the largest single shipyard in the world.36

Sun’s large black workforce belied the company’s reluctance to comply with Roosevelt’s Executive Order. The Pews only embarked on the mass hiring of blacks to confound unionization efforts and to rebuke McClure for his lapse in loyalty to the very company that had resurrected his political career. Hiring a large number of black workers provided a temporary political fix for the company’s dual problems of an encroaching Democratic union and an increasingly fickle Republican political machine. The Pews employed a race strategy that (barely) complied with Executive Order 8802 and subverted the organizing efforts of the IUMSWA. In May 1942 the company announced a plan to open a fourth production yard that would employ blacks exclusively; seven months later, Sun Ship’s Yard No. 4 opened. By June 1943, 6,500 of the approximately 15,000 black workers employed at Sun Ship worked in Yard No. 4.37

The national office of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) quickly condemned Sun’s Yard No. 4 as a violation of Executive Order 8802 and a clear setback for ongoing campaigns of racial integration in the workplace. Given that blacks and whites were already working together in three of the company’s yards, the NAACP challenged the need for a separate all-black yard.38 However, the vast majority of Chester’s black population welcomed Yard No. 4. First, its opening meant that many more jobs were available and only to black workers. Second, although wartime production demands opened up some skilled positions, in the other Sun yards black workers were largely confined to unskilled jobs. Separate and unequal pay scales for whites and blacks were the norm. As a fully operational unit, Yard No. 4 hired blacks for the entire range of production positions. The company trained local black workers as welders, plumbers, and electricians. Pew also recruited graduates of black colleges in the South and from the federal Engineering, Science, and Management War Training Program operated by the Works Progress Administration.39 For Chester’s working-class blacks, Sun’s vocational training, higher wages, and promotions offered a real chance for economic advancement in an otherwise openly discriminatory labor market.

Despite criticism of segregation at Sun, the opening of Yard No. 4 put Pew in compliance with the employment demands of Roosevelt’s War Labor Board. But Pew’s purposes for Yard No. 4 were expressly local. The IUMSWA’s platform called for improved conditions for black workers at Sun. But the superior workplace benefits existed only in Yard No. 4, as Pew intended. Given the well-publicized and innovative benefits the yard provided its employees, Pew expected loyalty from Chester’s black community and support in his antiunion and antimachine efforts. Pew achieved some measure of success at both, as evidenced by Yard No. 4’s record membership in the SSEA. In the NLRB’s second consent election in 1943, 4,700 Yard No. 4 workers voted in favor of Pew’s SSEA and 700 for the IUMSWA.40 By contrast, the majority of black workers in the other yards stayed home on Election Day, fearing violence from angry white coworkers. The IUMSWA won the consent election by a slim margin: 12,835 votes for the IUMSWA to 11,922 for the SSEA.41

For Pew, support for Yard No. 4 in Chester’s black community could potentially thwart the machine’s lock on the local Republican Party. McClure’s ongoing efforts to secure the favor of the IUMSWA and the labor vote at Sun undermined Pew’s SSEA. In response, Pew publicly endorsed and financed a rival candidate to McClure’s handpicked choice for the state senate in the Republican primary. The loyalty of Yard No. 4 workers to Pew’s candidate proved no match for the machine’s ability to procure a favorable voter turnout.

Pew’s efforts failed, but Yard No. 4’s black workers’ support for the SSEA exacerbated existing tensions between white and black workers (regardless of black workers’ support for the IUMSWA in the other yards).42 As in similar labor standoffs around the country, Pew in effect used the existing black-white tensions to “divide and conquer” and weaken the efforts of organized labor. By escalating racial tensions, “a certain amount of employer-employee antagonism [was] diverted into intra-employee conflict.”43 Yard No. 4 had less effect on worsening tensions in Chester. McClure’s political machine easily fended off a challenge from black shipyard workers and their families. If anything, Pew’s efforts created a minor division within the black community partially along class lines between Sun workers and black machine lieutenants and small business owners. The consequences of Pew’s racial maneuvering were short-lived. With the end of World War II, the number of Sun employees in all yards declined, and Yard No. 4 was closed.44 While employment competition between black and white workers clearly exacerbated existing racial antagonism, Pew used Yard No. 4 to stoke the embers of racial divisions in the working class and gain economic benefits.

Race Matters

Prior to World War I and the accompanying (and overwhelming) growth in the city’s industrial economy, black and white relations appeared of no great concern to the social dynamics of everyday life in Chester. Racial discrimination and inequalities were widespread and obvious but at the same time, normalized and subdued as a result of “McClurism.” Rapid social changes abruptly upended the political machine’s ability to manage racial divisions and benefit handsomely from them, unleashing the wrath of white privilege in the race riot of 1917. Race, as a consequence, became the defining factor in reshaping the geography and social life of the city. What can be learned from these instances when race becomes central? Race did not simply appear or percolate to the top of community and later, workplace concerns. Its centrality to spaces of both residence and employment was intentionally trumped up and aggravated to benefit the political machine and local industrialists.

The events depicted in this chapter point to the historical ascendance of a systematic and strategic manipulation of race for practical political and economic purposes. Black isolation and exclusion became utilitarian, a means to profit from urban development and control workplace conditions. Racial divisions became the preferred standard for dividing spaces and imbuing them with differing levels of economic and social value. Race, then, was intentionally chosen as the ordering mechanism for the development of the city and its suburbs.