3

How to Make a Ghetto

Throughout the years of World War II, Chester experienced a housing crisis. Thousands of black and white workers had crammed into the small city, drawn to employment in the waterfront’s industrial war machine that built ships and churned out munitions day and night. In addition, demand for housing trebled when the war ended and the troops returned home, but only for a short while. By the late 1940s the pull of the suburbs reduced Chester’s population, just as it did in similar cities in the Northeast and the Midwest. During this short-lived shift from too much housing demand to not enough, entire neighborhoods remained racially segregated. Suburbanization altered the realities of racial segregation, but only in its scale. Chester became smaller, poorer, and disproportionately black, and the towns and subdivisions of surrounding Delaware County became larger, wealthier, and overwhelmingly white.

This quick synopsis of the growth of the suburbs and the ensuing changes and challenges to Chester conforms to the established narrative of American postwar suburbanization and urban decline. In the second decade of the twenty-first century, this history is well-known, primarily because Americans still live with many of the postwar era’s debilitating consequences for its older cities. Yet perhaps as a result of its repeated retelling, the detailed racial mechanics of this process have been lost, ignored, or glazed over at best. This chapter pulls apart the “postwar ghetto and suburbanization” narrative and focuses on the institutions and actors to investigate racial exclusion as a means for regulating the city and developing its suburban hinterlands. It examines the political and administrative coordination involved in pushing racial exclusion from the city to its suburbs. Together, these actions point toward the intentionality, not the inevitability, of suburban exclusion, that suburban development was a collective spatial fix for actors and institutions to both cope with and profit from the pressures of racial integration.

Underlying the rise of the ghetto and the suburb were deep concerns among whites to preserve the racial status quo and fight off threats to undo it. The collective fears of whites conformed to the dominant racial ideology of the time, but they were also strategically stoked by the localized race-baiting by actors and institutions with vested interests in urban and regional change. The chapter begins with the story of a failed effort in the 1940s to construct an all-black private market housing development in Chester called Day’s Village. The Day’s Village story reveals how a race-based strategy facilitated postwar urban segregation, the use of residential restrictive covenants, racial steering, and the other decisions and actions to prevent racial integration in both the city and its expanding suburbs. The chapter closes with two stories of racial violence in 1958 and 1963 in suburban Delaware County. Both stories bring to light not only the most appalling aspects of racial exclusion but also the degree to which entire communities bought into the production of the suburbs as a defensive spatial fix to the threat of racial integration.

Day’s Village and the Complexities of Racial Segregation

For the first half of the twentieth century, Chester’s fate was ruled by the industrial boom-bust cycle that regulated the city’s economy, much of its social life, and the fluctuations in its population. By the time the city’s industries geared up for a second war effort in the early 1940s, its housing stock bore evidence of past overcrowding followed by near abandonment in the Great Depression. The boom-bust economy clearly took its toll on the city’s urban infrastructure. Indeed, there was no incentive to build new housing in the 1930s and the first half of the 1940s. Landlords simply raised rents and packed in more tenants during periods of high demand and during slowdowns allowed properties to age without repairs or upkeep.

As bad as the substandard housing conditions were for white residents, they were much worse for their black counterparts. Although Chester’s black population grew in response to the recruitment of unskilled and semiskilled industrial workers from southern states, the spaces in the city designated as “Negro neighborhoods” following the 1917 riot remained the same size. In 1940 nearly 60 percent of the total black population resided in the city’s Eighth and Ninth Wards. Most of the several thousands who relocated for work during the war stayed on as residents in these confined, segregated neighborhoods. Black communities were further divided by status, tenure, and social class, with the middle-class, longer-term residents maintaining homes in prized sections of neighborhoods and newcomers renting beds in flophouses or tripling up in small rooms in subdivided, aging, and decrepit homes.1

The dismal conditions of everyday life for blacks in Chester in the 1940s were spelled out in the Survey of Race Relations and Negro Living Conditions in Delaware County (1946), part of a report commissioned by the National Urban League. The survey labeled the housing shortage “serious” and found “practically no new homes for Negro occupants having been constructed in the county for nearly 20 years.”2 Half of the black population lived in antiquated dwellings without adequate sanitation, ventilation, or heat. The survey laid most of the blame on segregation. By the early 1940s wartime restrictions on new housing construction, growth in industrial employment, and unyielding racial segregation caused demand to far exceed Chester’s limited and dated “black housing” supply. However, the possibility for a vast improvement in the bleak situation appeared on the horizon in 1942. First, the recently (1939) formed Chester Housing Authority (CHA) opened the 350-unit Lamokin Village in the Ninth Ward. Lamokin Village was not only the city’s first public housing development, it was also its first segregated one, comprised entirely of black tenants. The opening of Lamokin Village eased demand for “black housing” somewhat (rather than build on an undeveloped parcel, the CHA razed 149 Ninth Ward homes, registering a net gain of 201 new housing units).3

A second promising remedy to the “black housing” crisis appeared the same year. The high-stakes real estate developer Joseph P. Day proposed an ambitious plan for newly constructed private market homes for Chester’s black families. Day was a pioneer in large-scale real estate development. Based in New York City, he oversaw the development of thousands of housing units in cities in the Northeast. He began as an auctioneer, selling thousands of lots in Queens, New York, and the parcels later developed as Hunts Point in the Bronx. His early days as an auctioneer brought him to Camden, New Jersey, where he successfully sold hundreds of government-owned wartime housing units, and to Chester. In 1922 the U.S. Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation contracted Day to auction 278 homes, 23 apartment buildings, and 75 vacant lots in Chester’s thirty-five-acre Buckman Village. At the height of World War I, the Shipping Board had purchased land and developed Buckman Village to house shipbuilders and other industrial workers employed at Sun Shipbuilding and other industries along the waterfront. “When the war ended this activity stopped almost overnight,” according to the New York Times, “and Chester entered into an industrial depression of great magnitude.”4

In the twenty years after the Buckman Village auction, Day became a major developer, constructing large tracts of homes in Brooklyn, northern New Jersey, and Connecticut. He championed home ownership for average working-class Americans in the midst of the Great Depression and was an early advocate for the mass adoption of then-novel long-term residential housing mortgages. In 1942 Day returned to Chester at the height of its demand for housing, proposing 150 new homes for black families to be built on a tract of land abutting Highland Gardens, an all-white residential community. Day and a handful of other developers saw demand for (and profit in) black housing developments in northeastern cities experiencing an influx of wartime workers. Chester seemed ideal for the segregated project for blacks called Day’s Village.

The plan for Day’s Village met with immediate opposition from the residents of adjacent Highland Gardens and its chief financial underwriter, the Connecticut Life Insurance Company. The development of Highland Gardens was considered a feat for housing-poor Chester. The all-white community of seven hundred brand-new single-family, attached (row) houses opened in 1942, the same year Day proposed his project. Both Connecticut Life and the new residents claimed that the close proximity of Day’s Village would threaten Highland Garden’s property values. They argued that the proposed increase in residents would overburden local roads and water and sewer systems and overstretch the capacities of neighborhood schools (which were all white). Day contended that the site was ideally situated for the size of the project he had in mind. Plans for the site complied with the specifications for Federal Housing Administration (FHA) insurance, and the project won the first rounds of FHA approval. In addition, Day received favorable purchase options on the land where Day’s Village would be constructed. The owner of that property was Chester’s Republican political boss McClure.5

In response to the complaints, the FHA proposed that Day build his project in an all-black neighborhood instead. Day declined, and the agency, under pressure, eventually backed down from its approval to underwrite the construction of Day’s Village. Day’s purchase option expired and the plan for modern housing for Chester’s black families vanished. McClure quickly sold his property to the CHA to build a very different community—a segregated white public housing project called McCaffery Village.6 In spite of civil rights achievements and significant federal and state antidiscrimination legislation that followed in the ensuing decades, McCaffery Village remarkably remained a solidly all-white community until the early 1970s.

Although it was never built, there is much to be gained from the story of Day’s Village. The broad contours of the saga—white protests over an adjacent black community and fears of racial integration in schools—are clearly not exceptional, given the state of race relations in 1940s America. Yet as the following sections reveal, the Day’s Village story demonstrates the unyielding intentionality in and commitment to racial exclusion in urban and regional development. The Day’s Village dispute speaks to the complexities of segregation for the early civil rights movement, the importance of racial exclusion to private and public housing, and the significance of race strategies to the political economy of suburban development.

The Limits of Civil Rights Activism

The Day’s Village saga illustrates the capricious political nature of racial exclusion not only as a strategy of uneven urban development but also as a focal point for resistance to it. First, Day’s proposal and the resistance to it posed a quandary for Chester’s progressive black leaders. Day’s Village, after all, called for a segregated all-black community. Given its mandate in favor of racial integration this proposal was something the NAACP, the key national civil rights organization, found difficult and ultimately impossible to support. The prospect of an all-black community conformed to and upheld the expectations of racial segregation as defined and policed by whites. Yet in a twist, whites rejected Day’s Village because its planned location outside “black space” threatened to upset existing racial boundaries, a prospect Chester’s black civil rights community found appealing. Further, key parts of Chester’s black community supported an all-black development but in a historically all-black area of the city. For many established black families and community leaders, the flip side of segregation had provided the chance for advancement in social class. This was true especially for those with connections to the local white power structure.

For George Raymond, who became president of the local chapter of the NAACP in 1942, the controversy over building Day’s Village amounted to a serious challenge to the struggle against racial discrimination in Chester. Thousands of blacks worked in Chester’s war industries but were denied decent housing and were relegated to racially segregated and overcrowded slums.7 But Raymond found little support or traction for making Day’s Village a high stakes issue either nationally or locally. Raymond focused on the objections to the project’s proposed location, specifically the Highland Gardens residents’ charges that blacks living nearby would lower their property values. He was convinced the FHA’s decision to rescind approval for the project was the result of such charges, a claim the FHA denied. In his petition to the national NAACP, Raymond cited the FHA’s decision as “flagrant evidence of bias.”8 But the NAACP viewed Day’s Village, a segregated housing project, as incompatible with its ideological and practical goals of racial integration and chose not to take up the issue.9

The fact that Raymond found little traction for the Day’s Village issue at the local level reveals the thornier dimensions of persistent spatial segregation and activist efforts to undo it. The residential separation of blacks and whites had clearly hardened over the decades since the 1917 riot; Chester was a fully segregated city in the 1940s. The city’s busy retail and entertainment district barely tolerated black customers by providing separate services or banned them altogether. Its central hospital maintained different wards for white and black patients. White and black students attended separate public schools until the ninth grade.10 The scale and longevity of hardened segregation inevitably produced a separate and viable community life. Middle- and working-class black neighborhoods matured as communities, with churches and civic organizations and black-owned shops, restaurants, bars, and funeral homes. As chapter 2 pointed out, Chester’s white elites and government leaders actively fostered a dependent black leadership, bestowing various favors, political appointments, and a share of often ill-gained cash. Black political incorporation was a strategic and highly useful tactic. The spatial politics of the ward system nurtured the “cooperation” of black leaders (and a large part of the middle class). “Chester’s native-born blacks knew their place,” writes the Delaware County historian McLarnon. “Most accepted the fact that Chester was a segregated city, with all that such segregation implied.”11

For Chester’s blacks, segregation was both unfair and compulsory; their acquiescence or acceptance of it as a fait accompli mattered little. What mattered was that segregation had seeped fully into the dimensions of everyday life, providing countless collective and personal obstacles and some opportunities. The reality of segregation provided a degree of certainty, especially following the violence of 1917. A change in the status quo was much desired, but improvement in housing opportunities and social reform was far from guaranteed. As head of the NAACP, Raymond was fully aware of the skepticism and fear of change in the black community. More importantly, he knew Chester’s white elites had set down the unwritten rules for black acquiescence and compliance and enforced them through carrot-and-stick favors and retributions. But Raymond understood that a radical change in local politics was essential for social change.

After Day’s Village, Raymond spent the next half decade tackling Chester’s segregation head-on. In 1945 he put together an all-black reform ticket for the city council, magistrate, and school board elections that ran on a platform for improving working-class housing, schools, police services, and support for black businesses.12 The ticket was handily defeated by the candidates the white political machine sponsored, especially in the black precincts. After a similar failed effort in 1947, Raymond abandoned his elections strategy. Chester was a closed society and the way to move forward was to acknowledge the resilience of the local political machine and work within and, to the degree possible, around it.13 To the dismay of a small but ardent group of reformists, Raymond adopted a gradualist approach to civil rights in line with the local moderate Old Guard led by self-professed “practical-minded” church leaders. Key among these was the Reverend J. Pius Barbour, a respected elder in the black community who was a mentor to the young Martin Luther King Jr. when he was a student at Chester’s Crozer Theological Seminary.14 Barbour advised Raymond to act measuredly and patiently and to focus on long-range goals. Raymond had greater success in fighting discriminatory practices in public and commercial spaces than in his efforts to combat housing discrimination and residential segregation. His achievements included the eventual end of segregated accommodations in restaurants, theaters, and hotels..

The Unyielding Commitment to Racial Segregation

For Chester’s whites, Day’s Village threatened to upend the spatial compact that formed the basis of the city’s full-on black-white divide and the range of social, cultural, and economic privileges that came with it. Whites had grown accustomed to such privileges accorded by a segregated city policed and micromanaged by their local Republican political leaders. To them, Day’s Village was yet another possible encroachment of their turf by blacks and an added reminder of the city’s demographic changes, the threat to the status quo, and the emerging possibilities opening up in the suburbs. In this instance, the Day’s Village story is instructive to an understanding of how the city’s power holders played into the white community’s fear of racial integration to shape the political and economic contours of urban and suburban development.

Day’s Village was the largest but not the first proposed private residential development that threatened the status quo of racial physical segregation. But such threats were few and successful threats exceptional. After the 1917 riot whites in Chester felt compelled to maintain, by lawful and unlawful means sanctioned by city leaders, the boundaries between white and black communities. Residential restrictive covenants dated back to the early 1920s. They increased after 1926, when the U.S. Supreme Court validated their use to prohibit individuals from specific racial, ethnic, and religious groups from living in certain neighborhoods. Racial covenants in neighborhoods such as Highland Gardens were enforced by unwritten arrangements between builders, realtors, the city’s building and permits department, and political ward leaders. Local banks rarely approved residential loans without such restrictions implied in the sale contract. The National Urban League’s 1946 study of racial conditions in Chester and Delaware County noted that Chester’s “system of unwritten restrictive covenants” was a highly effective means of preventing blacks from renting or purchasing homes except in certain designated areas (namely the Eighth and Ninth Wards).15 Although the Supreme Court overturned its decision on covenants in 1948, the new ruling applied only to the enforcement of deed restrictions. Secretive covenants between buyers and sellers remained common.16

Exclusionary efforts redoubled as the increase in the numbers of black industrial workers stretched the occupancy of neighborhoods and brought on demands for new housing. Given the power of Republican ward politics, local white control over the spatial allocation of private housing proved manageable and predictable. The machine oversaw building permits and the inspections process, enforced zoning ordinances, and held considerable sway over the practices of banks and other lending institutions. According to the Urban League’s study, private landowners actively blocked plans by home builders to construct new housing for blacks in undeveloped spaces, even on the fringe of the city. The “self-administration” of blacks in specific electoral wards by machine-sanctioned black leaders kept “troublemakers” and any plausible threats to the spatial status quo in check.

Yet Chester’s racial status quo seemed vulnerable to “external” developments on the horizon. The nation’s turn toward government-sanctioned, subsidized housing posed conceivable problems for the persistence of the city’s segregation in its current form. Public housing policies pertaining to financing, site location, and tenant selection were written at the state and federal levels, beyond direct local political influence. Federal housing policy generally addressed a national housing crisis and reflected progressive interests in solving problems of housing affordability. The local NAACP saw the promise of federal housing policy as an external and therefore progressive means to alter the city’s built environment and combat racial segregation.

The promise of relief from housing segregation was short-lived. Federal housing policy was ultimately administered with considerable autonomy by local public housing authorities. From the onset, the McClure machine folded the newly available opportunities provided by federal public housing financing into the patronage operations of the machine, including rewarding loyal operatives with seats on the Chester Housing Authority (CHA) board, which chose site locations for projects, awarded contracts for the construction of projects and their maintenance, and most importantly, oversaw tenant selection.17 Before the first bricks were laid and the mortar dried, the machine compelled black ward leaders to buy into plans for fully segregated public housing projects (or face the option of none at all).18 The all-black Lamokin Village was completed in 1942 and one year later the CHA opened two all-white projects, McCaffery Village (350 units) and William Penn Homes (300 units), in the city’s Seventh Ward. The CHA’s tenant selection office enforced a strict policy of racial segregation in all three projects.19

Despite vast changes in national urban policy after the war, Chester’s public housing situation changed very little. The city government readily dealt with any potential policy threat to segregation. In 1946, for example, local housing authorities who administered federal policies adopted income criteria for the selection of tenants of “low-income” government-subsidized projects across the United States. The CHA began to enforce the income ceiling policy in June 1947, issuing lease termination notices to now-ineligible tenants in the all-black Lamokin Village and the all-white William Penn Homes and McCaffery Village. The vast majority of the war workers housed at McCaffery and Penn earned incomes well above the low-income eligibility criteria. The CHA estimated that 60 percent of the residents of all three projects were ineligible under the new income ceiling policy; Lamokin Village had the smallest share of ineligible residents, with 166 of 350 units to be made available there.20 The purpose of the new federal policy was to free up housing units for low-income families. The expectation was that as families with incomes too high to remain in public housing departed on their own accord or were evicted, more units would be made available to needy low-income residents.

Given Chester’s demographics in the late 1940s, the majority of the city’s low-income families were black. That fact coupled with the discriminatory practices of private housing landlords meant that the demand for housing among low-income blacks was exorbitantly high. Seeing an opportunity for racial integration, Raymond publicly pressed the CHA to enforce the federal policy and rent the vacated McCaffery and Penn units to income-eligible blacks.21 Instead, the CHA maintained its practice of tenant segregation while complying with the new policy. In 1948 the number of vacant public housing units increased due to evictions, but the CHA intentionally left the units vacant. The CHA chose to maintain the segregation status quo; no blacks were housed in either Penn or McCaffery.22

Chester’s white leadership remained committed to preserving the racial status quo at considerable expense to the housing concerns of its citizens. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1948 decision striking down restrictive covenants in private housing had only a negligible effect on racial segregation, given the political machine’s direct and indirect control of the housing market. It did, nonetheless, spell the end of racial segregation in public housing. As pressures from Washington, D.C., Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and Raymond’s NAACP mounted, the CHA begrudgingly took initial steps to integrate over a period of three years. Pennsylvania’s governor eventually intervened, replacing the chairperson of the CHA with a nonmachine Democrat who favored desegregating public housing. In December 1955 the CHA finally passed a resolution formally abolishing segregation in all Chester public housing projects. The action was partly due to Democratic control of the CHA board and partly due to threats by the NAACP to sue the city for violation of the Pennsylvania Housing Authorities Law. According to the CHA resolution, vacant units were to be allocated on the basis of need and income eligibility, not “race, religion, color or creed.”23 William Penn Homes was integrated over a one-year period. The CHA’s Democratic chairperson noted, “Despite the ill-informed and inconsiderate pressures upon us by those who fear any change, I for one, am glad we decided as we did.” He went on to say that desegregation was a “harbinger of things to come at a time of difficult, but necessary, historical adjustment.”24 But he was overly optimistic. Shortly after the resolution passed, the Republicans successfully ousted him.25

The announcement of integration plans for McCaffery Village met with quick opposition. The Republican city council members balked, claiming that the timing for further integration was unsuitable and, as the Republican John Nacrelli, future mayor of Chester, proclaimed, the area was “not yet ready to accept it.”26 When Raymond threatened another lawsuit, the CHA agreed to rent to three black families. The reaction of white residents was swift and violent—two of the homes were vandalized and CHA officials were threatened. According to McLarnon, when the new CHA director asked the mayor for police protection, “the mayor refused, claiming that the less publicity the situation received, the sooner tensions would ease. Absent aggressive support from city authorities, few blacks were willing to risk the move.”27

In clear evidence of the resilience of racial exclusion, Chester’s public housing remained segregated long after the announced end of the CHA’s formal discriminatory tenant placement policies. As noted earlier, McCaffery Village remained occupied exclusively by whites into the 1970s, while two other projects, Lamokin Village and Ruth L. Bennett Homes (built in 1952) housed blacks exclusively. William Penn Homes was officially integrated, but a vast majority of tenants were black. In May 1972 the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission ordered the CHA to “racially integrate its four older public housing projects, directing that tenant selection policies must result in occupancy that reflected the white-black ratio in all projects combined—80% black and 20% white.”28 The commission’s insistence that the city’s housing authority enforce a policy that was two decades old met with little resistance. By 1970 Chester’s white population was barely over half the size it had been in 1950.

Expanding the Scale of the Racial Divide

Even Chester, with its sophisticated apparatus of racial segregation, faced the inevitability of racial progress stemming from demographic changes, the achievements won by civil rights activism, and progressive federal legislation. But the status quo would not go away without a long fight and ultimately a well-developed strategy for whites to abandon the city coupled with an equally calculated scheme to exclude blacks from the growing suburbs. Whites won the battle over Day’s Village, and government agencies, realtors, and banks actively policed the segregated private housing market. White-controlled institutions such as the CHA kept the integration of public housing at bay far longer than Raymond could have thought possible. Indeed, in retrospect the longevity of segregation in Chester seems remarkable. And it is telling that its longevity was due to the diligent enforcement by individuals and institutions and not simply a consequence of changing market conditions that favored suburbanization. Such diligence became the norm throughout the rest of Delaware County. Suburbanization was but the active reproduction of the black-white divide on a larger scale, requiring a significant amount of energy to enact a more expansive racial order. At the heart of it, mass postwar suburbanization was a spatial fix for the eventual upending of the racial status quo in the city.

On its surface, the suburbanization of Delaware County was similar to that of most northeastern cities between 1900 and 1960. As in most metropolitan regions, city growth and suburbanization first occurred in tandem in the early decades of the twentieth century. Wealthier and middle-class whites began to leave Chester in sizable numbers after 1920. Between 1920 and 1940 the city’s white population decreased from 51,000 to 49,000. The downward trend was partially reversed between 1940 and 1950 as a result of the war industry and the return of veterans after 1945. First-ring suburbs grew quickly. The townships of Darby and Ridley, adjacent to Chester, were the first to show rapid growth in the number of lower-middle-class and working-class whites. Glenolden’s population rose from 1,944 in 1920 to 5,452 in 1950, and Sharon Hill’s population rose from 1,780 in 1920 to 5,465 in 1950. The populations of Ridley Park, Norwood, and Prospect Park more than doubled between 1920 and 1950. All these communities were primarily residential towns with some remaining farms, little commerce, and with few exceptions, no industry. Trains and then automobiles shuttled workers to and from their city jobs.29 In the 1950s white out-migration picked up pace and continued unabated for two decades.30 Between 1940 and 1960 the population of Delaware County increased by 250,000 persons, many of them working-class whites who left Philadelphia neighborhoods. By 1960 eight of every nine persons in Delaware County lived outside Chester.31 Meanwhile, in Chester between 1950 and 1960 the white population decreased by 18.8 percent, while the black population increased by 53.4 percent.32

The demographics of suburbanization—the changing racial and class geography of a metropolitan region—are informative, but they do not in themselves explain or shed much light on how and why regional changes occurred the way they did. To adequately address questions of how and why, we need to focus on racial exclusion as the key political and economic strategy driving urban and suburban development. Racial segregation shifted in scale, moving from spatial divisions within the city to divisions between the city and its suburbs. The geographic expansion of racial exclusion, so to speak, is the deliberate outcome of decisions by actors and institutions. Chester, already formed by a half century of hardened segregation, provided the political base or locus for suburban racial exclusion. The growth of the suburbs was less an abandonment of the city than an expansion in spatial scale of racial division.

The local politics of suburbanization strategically stoked and harnessed the racial fears and anxiety of whites across the class spectrum. As discussed above, Chester’s middle- and working-class whites were accustomed to a segregated city and fought hard to maintain it as such. Although the arising affordability of the suburbs was a pull to larger numbers of white residents (especially with the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act of 1944 or GI Bill), many clung to their city homes and familiar neighborhoods. The racial boundary lines between residential neighborhoods were increasingly put to the test, but they were also enforced and policed largely through intimidation and violence directed at black newcomers. As late as 1960 the local NAACP registered its concerns about the increasing instances of violent retribution by whites toward black newcomers on their blocks.33

In his book-length memoir the Chester native and New York Times columnist Brent Staples recalls his childhood in what was still a predominantly Polish and Ukrainian neighborhood on Second Street near Highland Avenue in the late 1950s. He tells of flying a wooden plane propelled by a rubber band that landed in the backyard garden of a Ukrainian family. The elderly white home owner snatched the plane, split it into several pieces, and returned it to Staples. “A beautiful plane had been reduced to splinters by a grandfather. Grandfathers were supposed to be nice, especially to children. I suspect that grandpa missed the days when black people were confined to small streets and alleys near the river; when the shipyard and the oil refineries were segregated, complete with supervisors for the colored; when the Poles and Ukrainians lived alone with their own, their schools, and their bakeries. Now black people were right next door. Grandpa needed someone to look down on.”34 Staples mentions the white strongholds of Highland Gardens and McCaffery Village in particular. “We knew instinctively not to detour as we came and went from school,” he wrote. “Keep to Highland Avenue: the message was delivered to us on the air.”35 As Staples’s memoir attests, the process of white flight was neither quick nor readily accepted. In Chester and similar cities whites clung to a dying racial order in part because many believed white institutions and politicians would step in and rescue them.

Chester’s well-managed political machine had provided the underlying institutional framework for the city’s entrenched segregation, mustering the powers of the housing authority, the police force, and the electoral ward system fueled by patronage. But the political machine also stoked the embers of racial integration and therefore, conflict. It was, after all, the Republican boss McClure who tendered the sale of the land adjacent to Highland Gardens to Day to build an all-black community, setting off a furor among his white constituency. McClure’s decision may seem surprising, but in the larger context of the politics of urban development, his tug on the seams of the very divisions he helped design and maintain makes perfect sense.

The political infrastructure that led to the eventual city-suburb racial divide was put in place by the outward expansion of the local political machine. As early as the 1920s McClure’s Republican machine realized the potential and the urgency of bringing the growing towns and villages of Delaware County under its control.36 The ability to acquire political control of the nascent suburbs required the skilled management and governance of Chester, a feat fully accomplished by the 1940s. For decades Chester police officers, for example, were election “poll workers,” reminding black and white voters to cast their ballots for Republican candidates while wearing their service uniforms.37 Following the elections, patronage jobs were (re)allocated to ward leaders according to voter turnout numbers.38 Many of these individuals, their families, and their social networks could be called on for similar “party work” in the suburban expanse.

The established political power base in Chester easily allowed the machine to extend its governance to the entire county.39 Chester’s Republican machine found little political resistance to its rapid expansion in the suburbs. The Republican Party dominated the growth of the Greater Philadelphia region (to the north of Chester), especially in nearby Montgomery County.40 In his discussion of Republican politics in Delaware County, McLarnon points to the Chester organization’s high degree of organization and party discipline in the nascent suburbs: “The foundation of the organizational structure was the party’s cadre of committee people—one man and one woman from each of the county’s 250 precincts, chosen at the primary election in even-numbered years. The committee people constituted the standing army of the machine. Each maintained continual oversight over his or her domain, paying particular attention to new arrivals in the precinct. When a family moved in, the committee person made the first political contact, insuring that the new neighbors understood the lay of the political landscape.”41 To help simplify expansion and control, McClure founded an informal executive committee, the Delaware County Republican Board of Supervisors, comprised of prominent local bosses charged with overseeing political affairs in designated regions in the county.42 As McLarnon argues, the genius of what was commonly known as the “War Board” was its ability to pander to the needs and concerns of each region of the county, including Chester. This facilitated an emerging racial divide between city and suburb, with Chester’s political operatives (including black ward leaders) playing to increasing demands for racial inclusion and integration in the city and their suburban counterparts reassuring home owners of their long-term investment in a white community. In one of the more striking examples of race-baiting, McLarnon tells of the 1961 countywide election in which the Republican Board of Supervisors in suburban Springfield had black party workers from Chester pose as potential Democratic home buyers, stoking white voters’ fears (and turnout).43

Chester’s political machine laid the systematic framework for whites to exit Chester and to avail themselves of residential opportunities and the security of an intact racial order, which were both available in nearby suburban towns and villages. As whites moved into newer housing in the small towns that dotted Delaware County, they often held onto their Chester properties, dividing them into rooming houses or apartments for black tenants with the consent of the McClure machine. The expansion of the city’s black neighborhoods did not occur willy-nilly; it too was politically managed. Unlike in larger cities, blockbusting—the sale of homes in white neighborhoods to blacks to encourage panic selling among whites—was finely coordinated and managed. Both black and white political ward leaders communicated and worked with realtors and home sellers in overseeing racial changes block by block. All the while, the political machine conveyed mixed messages regarding Chester’s prospects at integration or continued segregation. As demographic pressures and more progressive national efforts at integration evolved over time, so did the machine’s ambiguity regarding racial changes in the city. It is also important to note that the machine’s reach into the suburbs did not mark an abandonment of its hold over Chester. The machine kept its control over an increasingly black city well in place. As indicated, the expansion of Chester’s political control over Delaware County and its racial landscape was only made possible by the successful control of Chester, including the continued domination of the city’s black wards.

Its countywide political infrastructure intact, the Republican machine could rely on its networks in the construction and real estate industries and in credit and financing to actuate effective “racial steering” throughout the suburbs. The compliance of builders and realtors was assured primarily by the vertical integration of political appointments to the county administration, from supervisors to heads of agencies in charge of issuing building permits, licensure, and taxation. Information about suburban homes for sale, new developments under construction, sale prices, and financing opportunities were “tailored” according to the race of the prospective buyer. Pennsylvania laws overseeing construction lending and home financing favored local oversight and enabled discriminatory practices to occur with impunity. Out of state banks were restricted from lending in Pennsylvania, and in state banks were limited to lending in their home counties. According to McLarnon, in 1960 Delaware County was home to two large commercial banks, seven savings and loans, and twenty-five building and loan associations. The small size of the local banking community enhanced the machine’s capacity to approve or deny suburban home mortgages on the basis of race. Although national in scope, the mortgage guarantee and home loan programs of the FHA and the Veterans Administration were not immune from the prevailing racial biases in the local housing market. Loan officers at Delaware Valley banks and savings and loans could easily apply subjective criteria to determine which applicants were qualified, had sufficient credit, and demonstrated the ability to pay for the homes they hoped to purchase.

McClure’s Chester-based political organization did not cause suburbanization, nor was it responsible for the mass exodus of whites from Chester in the 1960s. But it clearly and effectively harnessed the racial fears among white city dwellers. Racial factors exerted far greater influence over the process of suburbanization than social class. While white flight is typically referenced in support of this claim, it is important to note that Chester’s racial politics formed the basis for exclusion in the suburbs. The political machine that enveloped the suburbs and overlaid the patterns of racial segregation countywide had cut its teeth in Chester. The factors that accounted for whites leaving the city are less rooted in individualized racial prejudice and attitudes than in the institutional practices that harnessed racial fears into collective anxieties and an impulse to move. The stoking of racial fears in the city to underscore the “message” of racial integration and the threat of depressed property values that accompanied the encroachment of black residents into all-white, working-class neighborhoods rendered the exodus to the suburbs practical and beneficial to builders, realtors, banks, and politicians.

Toeing the Line in the Suburbs

The rise of Chester’s suburbs was a spatial fix to the purportedly looming threat to whites of residential racial integration, stoked by institutional practices that both worsened the prospects for whites who remained in the city and offered sanctuary in the form of a single-family suburban home for those who left. By the late 1950s the underlying ethos of mass suburbanization was the idea that integration would damage white interests. For whites, relocating to the suburbs meant leaving behind city living and with it the prospect of living with black neighbors. The Republican machine’s political incorporation of the suburbs promoted this spatial thinking of race relations and promised to enforce it. The degree of violent response to any breach of this “racial contract” demonstrates the commitment to the expanded racial divide in the era of mass suburbanization.

Together, the set of discriminatory suburban housing practices drummed up and reproduced on an everyday basis by real estate agents, loan officers, and builders proved a daunting obstacle to blacks seeking to own or rent homes, regardless of their social class status. The Republican War Board openly sanctioned the exclusionary practices of realtors and lenders and turned a blind eye to the intimidation and harassment of potential black buyers by home owner associations. The prevailing public discourse that normalized racial exclusion legitimized suburban exclusion. Ideology, public policy, and the actions of private actors locked up the postwar suburb as the privileged domain of whites. Individual and organized efforts to fight suburban racial exclusion were further challenged by a lack of recourse to state and federal fair housing laws. The Fair Housing Act, Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act, was not signed into law until 1968. Nonetheless, some blacks (along with white supporters) resisted the suburb’s apparent racial order.

Quakers had long played a significant and active role in social justice issues in southeastern Pennsylvania, dating well before their principal roles in the Underground Railroad and the abolition movement. At the height of postwar suburbanization, Quakers prominently fought racial discrimination in residential real estate practices in Delaware County. In 1956 the early civil rights activist and realtor Margaret Collins founded Friends Suburban Housing Inc., a nondiscriminatory real estate brokerage firm. In the face of fierce opposition Collins pioneered efforts to sell homes in suburban Delaware County without regard to color. Meanwhile, other local fair housing advocates formed the Southeast Delaware County Area Committee of Friends Suburban Housing to lobby state and federal officials to pass antidiscriminatory legislation. These individuals spoke out against discrimination, often in conflict with fellow suburban Quakers who were concerned about their role in undoing stable communities. Broader support for integration among Quakers was not approved until May 1961, prompted by a statement printed in the Swarthmorean, the weekly paper of one of the county’s more high toned suburban towns: “As individuals concerned with the community of Swarthmore, our country, and our world, we declare our conviction that neither the color of a man’s skin, his nationality, nor his professed creed, are in any way related to his basic worth as an individual. We therefore believe that these characteristics should in no way prejudice the community’s response to individuals who desire to enter our boundaries, visit our residents, work in our homes or businesses, eat, play, or live among us.”44 Collins and her associates networked with area black civic organizations to assist families interested in purchasing a home, pressured other realtors to provide inventories of homes for sale, and whenever possible, listed homes for sale by supportive sellers. Many of Collins’s listings were homes foreclosed by the Veterans Administration. Friends Suburban Housing counseled black families before and after their moves to the suburbs and tempered the anger of white residents upset by the prospect of black neighbors.45

George Raymond, president of the Chester Branch of the NAACP, was one of the early clients of Friends Suburban Housing. A native of Chester, Raymond decided to relocate his family outside the city in the late 1950s. No stranger to the complications of fair housing and racial integration in Chester, he was acutely aware of the difficulties and potential dangers facing blacks moving to the suburbs. In the spring of 1958 the forty-four-year-old Raymond purchased an eight-room wooden frame farmhouse at 236 Sylvan Avenue in suburban Rutledge for $11,500. The Raymonds were the first black family to relocate to Rutledge, a small, all-white suburb five miles northeast of Chester. Raymond purchased the house from the Veterans Administration, which took possession after the former owner defaulted on mortgage payments. Friends Suburban Housing held the property listing.

On May 24, one day prior to the family’s planned move to their new home, an early morning fire consumed most of the house, rendering it uninhabitable. Although arson was immediately suspected, local fire officials cited the old electrical wiring as the likely cause. Two days before the fire, Raymond had requested the protection of the state attorney general’s office, citing concerns for his family’s safety based on a tip. A Chester Times reporter’s interviews with the town’s residents noted concerns that a black resident would spark an exodus of whites and a general resistance to “blacks mixing with whites” and “them living near me.”

A number of Rutledge residents faulted the methods of Friends Suburban Housing, calling their efforts to racially integrate the town “aggressive and sneaky.” Still others spoke of no communitywide prejudice but noted that black families should consider whether they would “fit into” Rutledge. As part of its effort to prevent violence and temper the hostility from townspeople, Friends Suburban Housing had already reached out to Raymond’s future neighbors before the scheduled move in date. The realty firm found no organized or neighborhoodwide plan to resist or protest the Raymonds’ intended move to Rutledge. Immediately after the fire, Raymond indicated that he and his family intended to rebuild the home. In February 1959, however, the Rutledge Borough Council passed an ordinance to condemn Raymond’s home and take possession of the property. Citing eminent domain, the council planned to raze the home and build a previously undiscussed municipal building. A judge upheld Raymond’s petition for an injunction after the town could not show adequate cause for taking possession of the property. A month later the council repealed the ordinance. Raymond had the home rebuilt, and he and his family moved to Rutledge.46

Subsequent attempts at suburban racial integration by Friends Suburban Housing met with both success and failure, if relatively unnoticed. Unnoticed, that is, until the late summer of 1963, when Friends Suburban helped a young black family purchase a home in Folcroft, a Delaware County suburban bedroom community sandwiched between Philadelphia and Chester. The family’s effort to move into their home set off what the local county newspaper called “a racial binge”—several nights of violence directed against the new home owners. The level of collective fury unleashed against a black couple and their young daughter in Folcroft was alarming; the incident revealed the intense commitment of whites to the suburbs as the spatial “corrective” to racial integration in the city.

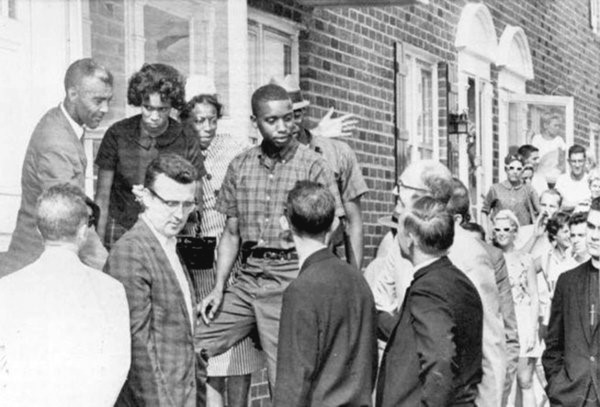

Horace Baker (center, in checkered shirt) and his wife, Sarah (second from left), pause at the door of their new home in an all-white neighborhood in Folcroft, trailed by a crowd.

In 1950, 1,900 people resided in Folcroft. By 1960 that number had risen to 7,861 residents, 3 of whom were black. Folcroft’s Delmar Village of twelve hundred units, one of a number of modest suburban communities built in the 1950s, featured small, brick row houses with tidy, postage-stamp front yards. Its residents—all white—were a mix of skilled industrial workers and white-collar clerical workers, many of whom had moved to Folcroft from Philadelphia. In August 1963 Horace Baker and Sara Baker purchased a two-story brick row house with blue shutters for just over $11,000 through the Veterans Administration.

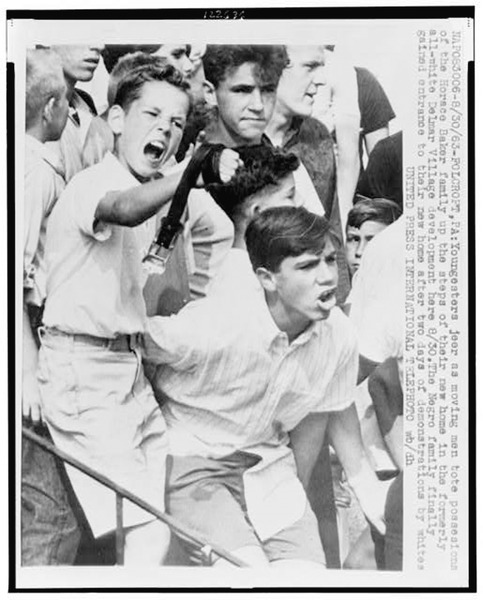

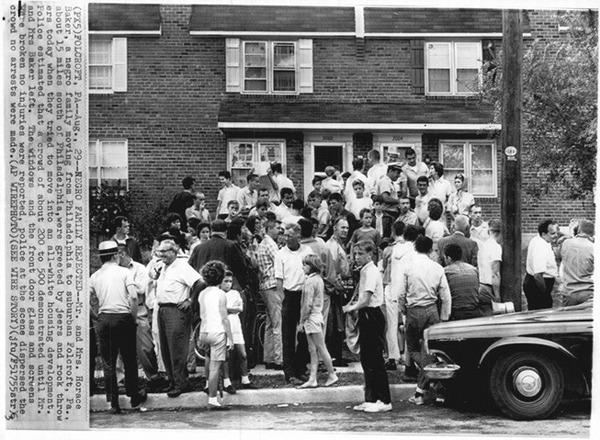

On the night Delmar Village residents learned that a black family had purchased the home, racial epithets were painted on its brick walls. In the two days that followed, all the house’s windows were broken, its front and rear doors were severely damaged, and the plumbing and electrical systems were vandalized. A crowd varying in size from twenty to close to a thousand kept vigil in front of the home the day of the Bakers’ anticipated arrival. The Bakers attempted to enter their home three times that day, only to be turned back by the angry mob. “A cursing, rock-throwing crowd estimated at five hundred persons threw yellow paint at their car and forced them to leave,” described one account. “The men of Delmar Village, at least most of them, were at their jobs. Wives and children met the Bakers to protect the all-white community.”47 When the crowd reached close to a thousand, the Folcroft police chief requested the assistance of the state police, who quickly sealed off the neighborhood to keep the crowd from expanding. The next day the Bakers attempted to enter their home with an escort of state police patrol cars. Glenn A. McCurdy’s 1964 account of the incident published in the Negro Digest describes the atmosphere prior to the Bakers’ arrival: “Numbering about eight hundred as the arrival time approached, the gathering had the appearance of a harmless community outing, a family entertainment. Children played in the street, running among the legs of adults standing there; teenage boys sat on the hoods of police cars, legs dangling; and wives with their hair in curlers pushed baby carriages up closer to the center of festive excitement so they wouldn’t miss anything.”48 McCurdy also recounts the intense jeering, swearing, and egg pelting directed at students from Chester’s Crozer Theological Seminary and black and white ministers from local parishes who came to welcome the Bakers. After the Bakers arrived and entered their home, the mob swelled in size and directed its animus at the state troopers ringing the home. The rock and bottle throwing continued into the night, subsiding around midnight. The Bakers’ front lawn, according to McCurdy, was covered “an inch deep in broken glass and garbage.”49 Eventually, one hundred state troopers controlled the crowd outside the Bakers’ home.50

Angry young boys gather at the Baker home, August 30, 1963.

One of the Bakers’ failed attempts to move into their new home. August 29, 1963.

The day after the Bakers took possession of their home, one hundred Delmar Village home owners issued a statement to the media deploring the violence and blaming “outsiders” (the NAACP, among others). They called for a boycott of any business “which serves or deals with the Bakers.” Their manifesto concluded: “We do not welcome the Baker family into our community. Perhaps this small borough can show this great nation that the federal government cannot force social integration upon the population.”51 In the weeks that followed, sporadic protests continued, but the violence and property damage subsided. Local ministers raised over $1,500 to help pay for repairs to the Bakers’ home, and the local AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations) fronted the costs of labor for the repairs.52 However, conditions did not improve and the Bakers endured verbal assaults and occasional violence to their home for months. In January 1964 the state Human Relations Commission filed injunction petitions against fifteen Delmar Village residents, including some borough officials, charging them with harassment. The state senate Democratic minority leader claimed that Folcroft was “synonymous with racial injustice throughout the world” and charged county and state officials with blatant indifference.53 With the harassment unending, the Bakers sold their house in 1966.54

Given the scale of the protest and the extent of the mob violence, the “Folcroft incident” received considerable coverage in both the local and national media. But neither Rutledge nor Folcroft was unique; both resembled similar efforts to exclude blacks in postwar suburbs across the United States. Neighborhood home owner associations monitored home sales, recommended and worked with like-minded realtors, and organized petition drives aimed at black buyers with purchases in escrow or against leasing homes to blacks. Suburban racial exclusion was practiced institutionally by banks and realtors and individually by white home owners, reflecting the commonly held sentiment that blacks should not live in white neighborhoods. Accordingly, should blacks pose a threat, it stands to reason that exclusion was deemed rational at any cost.55 Such thinking was prevalent in the working-class, first-ring suburbs that were home to large numbers of whites fleeing Chester and Philadelphia. More importantly, white county political leaders, home builders, lenders, and realtors legitimized racial exclusion explicitly or through unspoken actions. In addition to waging a difficult fight against housing discrimination, the work of Friends Suburban Housing laid bare the extent to which culpability was shared among the most vocal opponents to integration and those who remained silent.

On the whole, the political incorporation of the suburbs, the institutionalized mechanisms of racial exclusion, and the community-sanctioned intimidation and threats of violence prevailed, (re)producing the racial divide between Chester and the rest of Delaware County. Whites clearly dominated first-ring suburban towns surrounding Chester. The respective population numbers bear this out. Nearby Marcus Hook had 3,224 whites and 74 blacks; Tinicum 4,373 whites and 2 blacks; Eddystone 3,006 whites and 0 blacks.56 Meanwhile, in Chester the 1960 census registered a population of 63,000, of which blacks numbered 27,000, just shy of half the city’s residential total. Chester’s total population declined by 2,300 (-3.5%) between 1950 and 1960, with the white population decreasing by 9,700 (-19.0%) and the black population increasing by 7,400 (53.0%). The full brunt of racial division was also becoming apparent. Chester’s black unemployment rate in 1964 was 14 percent, compared to 7 percent for whites. In Delaware County the unemployment rate was 3.8 percent. Unemployment rates for blacks were twice as high as they were for whites in both 1950 and 1960. Most of the whites who left in the 1950s had higher education levels than the city average and were young adults and families leaving behind elderly parents (with lower education levels). The median age of the white population in 1960 was 32.3 years; for the black population, it was 18.7 years.57

Fear and the Intentionality of Exclusion

Chester’s postwar suburbanization and the ensuing black and white divide between the city and the county were similar to the processes in other metropolitan regions in the Northeast and the Midwest after World War II. The suburbs offered the promise of comfort, open space, and newly built homes within commuting distance to factories and offices. Indeed, many city dwellers weary of noisy streets and older, tiny homes aspired to the suburban lifestyle. But the postwar suburb was for whites only, and our existing understandings of the important processes of racial steering, blockbusting, outright discrimination, violence, and communitywide prejudice clearly apply to Chester. This chapter has sought to highlight the significance of urban segregation to city-suburban racial division, especially the degree of political and administrative coordination involved in pushing the scale of racial exclusion to the regional level. Perhaps most importantly, this chapter underscored the intentionality, not the inevitability, of suburban exclusion, that suburban development was a collective spatial fix that fed on and amplified white fear of and uncertainty about racial integration. The ideology of racial division was the guiding strategy of the stakeholders in the spatial development of the suburbs. Consequently, Chester was increasingly hamstrung politically and economically, as outlined in the next chapter. The resulting turmoil of the 1960s civil rights era proved to be yet another instance of race used as a strategy to promote spatial change.