4

The Birmingham of the North

Notwithstanding the considerable economic and social changes cities faced after World War II, in many ways black-white divisions in Chester remained simply more of the same. The departure of whites to working-class suburbs immediately to the north and west of the city continued apace. The stream of southern black families moving north for employment slowed somewhat as older manufacturing firms relocated or downsized, but in combination with new families, the city’s black population continued its steady rise. Yet in everyday terms the shrinking of Chester’s white population and the rise in black residents changed little in the racial status quo that governed core aspects of everyday life—where people lived, worked, went to school, bought groceries and clothes, saw movies, and ate meals. Chester’s boomtown feel still resonated in the early 1950s regardless of steady but small yearly declines in its manufacturing output since the end of the war effort. Downtown Chester was the center for shopping in the expanding Delaware County, with Sears and Roebuck and Kresge’s 5 and 10 dominating a vibrant business district populated by restaurants, beauty salons, barbershops, shoe stores, corner stores, banks, bowling alleys, and movie theaters. And whereas black residents were welcome to spend their money downtown, most businesses hired few black workers, and many maintained separate facilities for their black customers well into the late 1950s.

Postwar demographic and economic changes slowly put pressure on the city’s long-standing racial status quo and the seeming permanence of white-privileged Chester. Federal court rulings and national legislation targeting the segregation of schools and housing magnified the “work” of Chester’s white elites and institutions to maintain homegrown racial inequality. In hindsight and given the depth of commitment to segregation, the civil rights movement’s disruption of the racial status quo seemed inevitable. As this chapter recounts, Chester’s civil rights struggle in the early 1960s also factored into the local politics of suburbanization.

Speare Brothers Department Store, 7th Street and Edgemont Street, 1961, founded in 1921 and closed in 1973. Reproduced by permission of the Delaware County Historical Society, Pa.

Chester’s established civil rights leaders won incremental gains in improving conditions for black residents in the 1950s. The challenge to the racial status quo took a spectacular and explosive turn in the early 1960s. Over the course of five years Chester emerged as one of the key battlegrounds in the nation’s civil rights movement, earning the city a national reputation for public racial unrest. In the spring of 1964 the national director of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) called Chester “the Birmingham of the North.”1

Civil rights activism has deep roots in Chester, as local religious leaders and the NAACP advanced the cause of racial integration during the peak of overt racial antagonism and institutional discrimination in the 1940s and 1950s. This chapter provides an overview of early leaders and efforts before turning to a discussion of complex cleavages and opposing agendas in the black and white communities set on challenging or preserving the city’s racial status quo. As was the case nationally, internal struggles over tactics and the pace of change divided Chester’s main civil rights organization in the early 1960s. Beyond describing the internal dynamics of civil rights activism, however, this chapter shows how local political leaders shaped and manipulated organized mass dissent against racial segregation and discrimination to benefit their own political aims and financial objectives, namely, furthering the racial divide between the city and the suburbs. In addition to feeding divisions within the black activist community, white elites benefited in a self-serving way from fanning the white fears of racial violence and unrest that they deceptively sanctioned. Chester’s civil rights activism, then, unfolded against a backdrop of elite, seemingly contradictory interests in protecting the racial status quo and white privilege while exacerbating whites’ fears of civil unrest that fed an exodus to the suburbs.

Chester’s ruling white Republican machine had already eased the migration of fellow whites from the city to the suburbs, politically colonizing newly formed towns and unincorporated suburbs and extending its system of political favors to sway suburban residential and commercial developers, bankers, investors, and other business elites—all of whom benefited handsomely from the white exodus from Chester that trebled after the racial unrest and violence of the summer of 1964. They capitalized on visceral racial antagonism and fear, the unsustainability of the racial status quo in the city itself, and the failed efforts by local whites to hunker down and maintain privileges to the exclusion of Chester’s black residents. In the 1960s the Republican machine, now fully invested in the city-suburban racial divide, allowed the racial status quo it had helped build and orchestrate in Chester to fully unravel.

This story of racial manipulation suggests that the processes that led to the condition of the impacted ghetto, a story often explained as the result of large-scale economic and labor market changes in the American economy, have their foundations in a political agency that favored the exodus of white people and capital over racial compromise and integration. As this chapter demonstrates, white elites intentionally interceded in Chester’s civil rights campaign by covertly ratcheting up the scale of protests, answering them publicly with violent “law and order” crackdowns, and squashing efforts at compromise that might lead to racial integration. This duplicitous political strategy heightened racial antagonisms among residents in the city itself, ultimately ushering in black political control (described in later chapters) of a city economically and socially hamstrung by the flight of white residents and white-owned small businesses (and their capital).

Economic and Demographic Challenges to the Racial Divide

In many ways Chester’s economic and demographic changes a decade after the end of World War II duplicated those of small northeastern manufacturing cities such as nearby Camden, New Jersey, and Wilmington, Delaware, and larger ones such as Baltimore and Philadelphia. The waterfront industries continued to be the main sources of employment throughout the 1950s and 1960s, although the number of manufacturing firms and positions steadily declined over time. Sun Shipbuilding, Scott Paper, and the Philadelphia Electric Company remained the city’s biggest employers. Baldwin Locomotive closed. The Ford assembly plant shut down in 1960, shedding 2,300 manufacturing jobs. Total manufacturing employment in Delaware County declined 12 percent from 1950 to 1962, and between 1958 and 1962 the number of county manufacturing establishments fell from 415 to 385. Unemployment was 9.3 percent in Chester compared to 3.0 percent for the entire county. Black unemployment in the city was 14.2 percent, double that of whites at 7.2 percent.2

In comparison with suburban Delaware County, Chester’s labor force was concentrated in industrial manufacturing and low-paying service positions. In 1960 only 9 percent of Chester workers were employed in white collar clerical, professional, and managerial positions, compared to 17 percent for Delaware County. The median family income in Chester of $5,343 was considerably less than the county’s $7,289, reflecting the migration of middle- and high-income families out of the city into the suburbs. Indicative of residential suburbanization, Chester “imported” 11,500 employees from the rest of Delaware County while exporting 6,600 workers to jobs in the rest of the county. The out-migration of mostly whites occurred in tandem with the in-migration of blacks, whose prospects and earnings in manufacturing and service positions were curtailed. The 1959 median income for Chester’s black families was $4,059, less than 70 percent of the $5,880 median income for white families. A third of Chester’s families lived in poverty, with black families comprising 50 percent of the city’s poor and whites 25 percent.3

Chester’s economic changes were coupled with dramatic shifts in its population, especially in relation to the expanding suburbs of Delaware County. In 1950 Chester’s population comprised 16 percent of Delaware County; in 1960 the city’s total population of 63,700 comprised 11 percent of the county. As cited earlier, the total population had declined by 2,300 (-3.5%) between 1950 and 1960, with the white population decreasing by 9,700 (-19%) and the black population increasing by 7,400 to 27,000 (53%). Most of the whites who left for the suburbs in the 1950s were young, newly formed families with higher education levels than the city average. Overall, the city’s population in 1960 was a shrinking community of older, working-class whites (with a median age of 32.3 years) and a growing number of young blacks (with a median age of 18.7 years).4 Black residents over the age of 25 averaged 8.4 years of schooling. Residential segregation prevailed, with over 80 percent of the entire black population residing in five contiguous census tracts in the central part of the city.5

Old Guard Civil Rights Challenges to the Racial Divide

Unsurprisingly, Chester’s decades-old racial status quo creaked and groaned under the weight of the vast changes in the city’s economy and the composition of its population. The city’s black civil rights activists viewed the changes as an opportunity for racial progress but not as an occasion to shift their tried-and-true tactics of quiet resistance. Chester’s Old Guard civil rights activists kept to a pragmatic gradualist approach that relied on a mix of compromise with political elites and court challenges to compel white institutions to change. In the struggle to integrate schools, many older black residents were reminded that leaders working on behalf of white political elites provided important results, such as the opening of all-black schools and the hiring of black teachers and administrators in the 1930s. Thirty years later McClure appointees still served on the school board and hired principals and teachers who were “faithful” to the city-county patronage machine. They served as ward leaders and liaisons between the black community and white elites but functioned primarily as eyes and ears on the ground reporting directly to the political machine. Civil rights activists were consistently reminded that working with the local politics of the racial status quo defined (and defended) by whites was the prudent path to change, however slow and piecemeal. Local civil rights activists, ministers, and community organizers worked through the NAACP, choosing their battles with the white establishment and compromising, albeit reluctantly, to achieve results. They were older and had spent decades at work slowly carving out modest advantages for the city’s black community amid considerable racial hostility. By the early 1960s they found their brand of political action challenged by a new climate of assertive activism, both nationally and locally.

For two decades Barbour, pastor of Calvary Baptist Church, was the chief strategist of local civil rights activism. His reputation as a black leader was defined by his ability to work across racial lines to improve the everyday conditions of Chester’s blacks. An intellectual as well as a spiritual leader, Barbour’s measured and pragmatic approach to civil rights activism earned the respect of Chester’s blacks and white elites and drew national attention. In Chester Barbour was change advocate and peacemaker.

NAACP Bulletin, 1948. Courtesy of the George Raymond Papers, Widener University Archives.

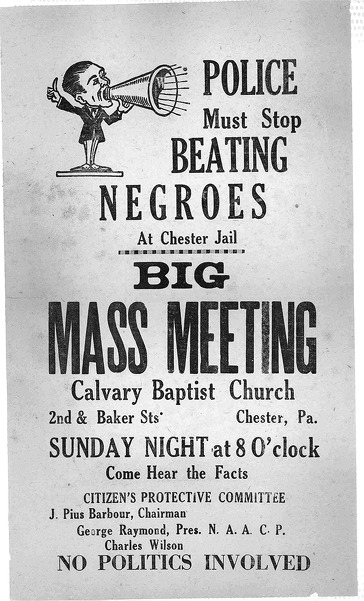

Calvary Baptist Church Meeting Flyer, 1952. Courtesy of the George Raymond Papers, Widener University Archives.

When pastoral duties were done for the day, one might see Rev. Barbour strolling along West Third Street, his black derby sitting at a rakish angle, sporting horn-rimmed spectacles and dangling a giant cigar between his teeth. At times he paused to chat with young folks or stood in front of the pool hall along with some of its habitués. Very often he would visit the office of Alderman Casper H. Green where local political figures frequently held court in the smoke-filled back-room. . . . Pius never failed to pen off letters to newspapers expressing himself on various issues. . . . Seldom getting actively involved in civic or political controversies, Barbour nevertheless maintained a friendly balance between the “Old Guard” and the “New Negro” as the leaders of the two Black factions were beginning to be characterized.6

Barbour played the diplomat to Raymond’s predilection to threaten legal action to advance the civil rights agenda. But Raymond too was a pragmatist. In his early years as president of the local NAACP, he had worked to end the segregation of public accommodations in restaurants, theaters, and hotels. That experience led him to believe that Chester was a closed society and that the only way to bring about change was to acknowledge and work with the entrenched Republican political machine that governed the city and had successfully co-opted the elites of the black community. Working with Barbour, Raymond understood that piecemeal reforms could accumulate as real progress over time.7

Both Barbour and Raymond viewed the odds of upending Chester’s legacy of racial segregation as shifting in their favor. Thanks to suburbanization, Chester was fast becoming a majority black city. The national civil rights movement was making progress even in the Deep South. Economic and demographic changes threatened to upset Chester’s racial order, as the boundaries of white neighborhoods slowly gave way in the wake of continued white flight and expanding numbers of black residents in need of housing. The racial covenants and other collective, neighborhoodwide efforts to defend the status quo tore at the seams, as individual home owners chose the expediency (and money) of renting or selling to black families over a commitment to racial order. Chester’s decades-old racial status quo was clearly not sustainable.

Challenging public school segregation proved much more difficult, however. For decades the local chapter of the NAACP, with support from black churches, kept the demand to end segregated public education at the top of the local civil rights agenda but achieved little success. White parent associations compelled the school board to aggressively defend racially segregated schools. In 1946 the NAACP worked with a committee of black parents to organize a student strike at a decrepit and overcrowded elementary school, demanding integration of students and teachers (who were assigned to work at black or white schools according to their race). In the fall of 1946 the school board agreed to integrate the city’s public schools. But the decision held only symbolic value, as organized opposition by white parents delayed changes and an administrative loophole permitted them to transfer their children to predominantly white schools.

In the fifteen years following the school board’s promise to end segregation, very little changed in Chester’s public education. In 1954 Raymond threatened to take additional legal actions after the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka declared separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. In response to the Brown decision and ensuing threats of lawsuits, the Chester school board devised and implemented a “neighborhood schools” plan to legally comply with the desegregation of Chester public schools. Neighborhood schools would accept all students regardless of race, creed, or color, based on their residence within neighborhoods whose boundaries were determined by the board. Chester’s school board, elected politicians, and white residents found this decision palatable and easy to accomplish, especially given that residential segregation would ensure the de facto racial segregation of schools.

The board’s policy of neighborhood schools, in effect, hardened its commitment to segregation. As the racial composition of the city changed, the neighborhood schools policy remained intact save for the redrawing of neighborhood boundaries to reflect the shrinking sizes of white neighborhoods. The board first established neighborhood boundary lines in August 1954 that reflected the racial topography of Chester. An investigation in 1964 revealed evidence of unofficial redrawing, including an enlargement of the zone for the all-black schools to reflect the growth of a black neighborhood. Consequently, public education in Chester in the early 1960s resembled that of fifteen years earlier: one high school, four junior high schools, and eleven elementary schools. With the exception of the racially integrated high school, all the other schools were either fully or highly segregated. In 1963 the enrollment in three of the eleven elementary schools was 100 percent black, while two others were just over 80 percent. The black majority schools were “mostly old wooden structures, poorly heated, crumbling plaster walls and ceilings, with peeling paint, drafty windows, small classrooms, and inadequate bathroom facilities, with ‘hand-me-down’ books provided to black schoolchildren.” The number of black teachers comprised just under a third of the four hundred and fifty teachers employed by the Chester school system.8 With aging infrastructure, poor funding, and overcrowding, school standards and performance continued to decline, as exemplified in the case of Franklin Elementary School. Built in 1910 for an enrollment of five hundred students, the school was never remodeled or expanded. In 1963 the school’s enrollment stood at just over one thousand students, 99 percent of whom were black.9

Local church and civil rights leaders challenged the Chester School Board’s neighborhood school policy on the grounds that it fostered the segregation of students and educators. The board acknowledged that a racial imbalance existed in individual schools but contended that this was an outcome of prevailing residential patterns, not board actions or policies. As such, school board leaders claimed they were neither legally bound nor financially able to address or fix the root residential causes of racial imbalance. “We have no segregation in the Chester schools. To talk about de facto segregation is not to talk about segregation but about a condition over which we have no control.”10 Regarding the demand that the district apportion all public schoolteachers to achieve the same proportion of black teachers to white teachers in each school, the board contended that teacher assignments were based on qualifications and educational reasons, not racial ones. In a moment of convenient historical amnesia, the board reminded the NAACP that Chester’s black community leaders had successfully petitioned the board for black schools with black teachers and administrators in the 1920s, three decades prior to the ruling that racial segregation was unconstitutional. The special counsel for the school board summed up the district’s position:

Most people think that the Chester School Board are guilty of segregation, that we take school children and because they are black, we send them to Negro schools. Most people think that we take children and because they are white, we send them to white schools. That’s what they think we are doing. . . . Now is the School Board responsible for the geography of the city of Chester? . . . But the geography of our city is a physical fact which has to be taken into consideration. Another physical fact is where the people live. The School Board has nothing to do with where people live. That’s a result of our society and a lot of conditions that all of us are very sorry about and trying to help in our feeble way, but it’s not something that’s in the control of the Chester School Board. . . . So what we’re talking about in Chester is not anything done by the School Board in the manner of segregation but the result of a social problem that has arisen over many, many years with very deplorable results, results that we all regret very, very much.11

The NAACP and the school board remained locked in protracted legal battles in which the board legally complied on paper while the NAACP sought to show institutional culpability in de facto school segregation. Both parties looked to the courts for a resolution. In the decade following the Brown decision, the school board maintained that it was up to the courts “to decide the question whether the maintenance and operation of a racially segregated public school system is lawful and non-discriminatory where such segregation allegedly arises out of racially segregated residential patterns in the City of Chester.”12 Meanwhile, the NAACP continued to rely on negotiation, compromise, and a legal course of action when necessary.

For its part, McClure’s Republican political machine easily tolerated and perhaps even accommodated the gradual pace and civil tone of local civil rights activism. Raymond and Barbour were reformists; neither threatened the underlying political basis of the racial status quo or the machine’s political and economic venture in the expanding suburbs. In the Annual Report of NAACP Branch Activities for 1961, for example, the local branch secretary reported to the national office: “There is something wrong with Chester. . . . The people here seem to live a carefree life. They seem to want us to fight their battles and don’t want to help.” The same report held the local Republican political machine accountable: “Chester is owned and operated by one man, Mr. John McClure. The people here seem afraid of this man’s organization. . . . Mr. John McClure has Chester sewed up, the people here seem afraid of losing their jobs or other things.”13

As the civil rights movement in the South and large cities in the North turned to tactics of civil disobedience and direct action, Chester’s strategy of quiet persistence seemed antiquated and increasingly inadequate. By the early 1960s the national civil rights movement, far from abandoning legal efforts to end segregation, had nonetheless begun to favor other movement tactics, such as direct action and collective protest. Chester’s young blacks in particular did not share Raymond’s patience with working with the political machine and grew frustrated with the slow pace of change. Consequently, membership in the organization declined; membership in 1962 was less than half of that in 1958. Chester’s black-white divide was no longer sustainable, but neither was the strategy of civil rights gradualism.

The question of de facto segregation in Chester was ultimately settled by commissions and courts but not before an upstart civil rights movement tried to end local racial discrimination through ongoing demonstrations in 1964, as outlined in the following section. As expected, politicians, the police, and the white and black ward lieutenants of the Republican machine denounced the civil unrest, sought to contain it, and eventually responded with state violence. But months of street demonstrations and protests revealed another side of the Republican machine’s role: whites’ fears of racial unrest were manipulated to further the demographic and spatial changes already enveloping the region. McClure’s hand in the civil unrest of 1963 does not diminish the intentions and purposes of collective action against racial discrimination. Rather, it reveals how powerful stakeholders can use the racial divide to further their political and economic interests in urban change. The aftermath of the unrest revealed that the Republican machine had little to lose and much to gain by ending the city’s racial status quo. The new realities of Chester and Delaware County—the exodus of the city’s white residents, the growth in its black population, and the intentional shift of political and economic power to the suburbs—meant the status quo in Chester was not sustainable even for the established political order. The question facing political leaders was how to favorably influence the outcome of black dissent.

Civil Rights Activism and Urban Unrest

Chester’s advocates for a more visible mass politics of collective civil rights action found a leader in Stanley Branche, a twenty-eight-year-old activist who came to Chester in 1962 and immediately began to shake up the local civil rights movement. Branche single-handedly brought the civil rights repertoire of pickets, sit-ins, and demonstrations to Chester. Within a few months Branche emerged as both hero and villain of Chester’s civil rights movement, but not necessarily along black and white lines. A report published after a year of racial protests and violence noted, “The Chester demonstrations and the whole present Chester civil rights movement have been essentially shaped by Stanley Branche.”14

Upon his arrival in Chester, Branche worked in the organizational ranks of Raymond’s NAACP. But he soon grew impatient with the slow pace of the organization. Branche criticized the antipopulist back room deals occasionally struck between NAACP leaders and white politicians and school board members. He lobbied the local NAACP to adopt direct action and mass protest tactics that would give the vast majority of Chester’s black men and women a meaningful stake in the immediate improvement of civil rights. Branche’s democratic tactics found little support among Old Guard gradualists, who worried that confrontation would upset order, prompt violence, and ultimately backfire. Undeterred and without permission, Branche began to recruit activists sympathetic to his call for direct action from inside the NAACP; Swarthmore, the nearby suburban liberal arts college; and the Swarthmore chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP). He formed the NAACP Young Adults to “put life into the Chester civil rights movement”15 as a direct action unit within (but not controlled by) the local chapter, placing the organization in the awkward position of providing emergency assistance to its dissenting members.16

In an attempt to quell or perhaps manage the growing dissent instigated by Branche, Raymond suggested the compromise tactic of threatening direct action and protests to compel change among white institutions. In April 1963 Raymond worked with Branche to challenge the hiring practices of downtown Chester’s large department stores, clothing shops, shoe stores, and other specialty shops. Although the shops welcomed (however reluctantly) increasing numbers of black residents as customers, the vast majority of retail employees were white. The two threatened the Chester Businessmen’s Association with a protracted boycott and pickets by black customers unless shops committed to hiring black employees. The prospect of a boycott worked. The association soon adopted a policy ensuring fair employment practices.17 But Branche was interested in more than the threat of civil disobedience.

Stoking Divisions within the Civil Rights Movement

In June 1963 Cecil Moore, the president of the Philadelphia NAACP, delivered a reproachful speech to a crowd of two hundred gathered at Bethany Baptist Church in Chester. Moore directly challenged Old Guard gradualism on Raymond’s turf, urging, “Negroes of Chester should not be afraid to burn shoe leather in picket lines and should not be afraid to go to jail fighting for their rights.” He reprimanded Chester’s black working and middle classes, including prominent ministers, attorneys, doctors, and politicians, for their blind commitment to “Uncle Tomism.” He took aim at the Republican Party machine, calling parts of the city “McClure’s pasture,” where a black man “sells his soul, gives up his rights for the privilege of participating in numbers, prostitution, gambling or for getting a ticket fixed or holding a political job for which he is not qualified.”18 Moore’s passionate speech may not have disclosed anything new, but it publicly acknowledged the cleavages between the Old Guard and the “New Negro” in Chester’s civil rights movement, lending legitimacy to the demands of younger activists led by Branche.

The well-worn conventional strategies for bringing about progressive change in Chester were quickly challenged. Chester’s mayor, Joseph L. Eyre, formed the Chester Human Relations Commission and turned to Raymond to recommend individuals to serve on its board. The NAACP Young Adults protested, charging that some of Raymond’s choices were “politically bound” with connections to the Republican machine, and that his seniority “doesn’t mean he represents the entire Negro community.”19 The internal dispute over legitimate appointees was never resolved, relegating the commission to the sidelines of the civil rights movement. Raymond felt obligated to remind the public that “general NAACP policy or expressions of official NAACP views on current problems will continue to come from me, as president, or from someone specifically designated to speak for me.” The Delaware County Daily Times capitalized on the apparent rift within the organization, editorializing that “some feel he [Branche] is a headline grabber using the civil rights issue to boost himself.”20

In the fall of 1963 Branche formally resigned from the NAACP, taking several younger members with him and forming a new activist organization, the Committee for Freedom Now (CFFN).21 His resignation, however, did not signal a final break with the NAACP, whose response to Branche and the CFFN was evasive. The national office officially disapproved of Branche’s flagrant disregard of organizational policies and local authority and branded him a rogue troublemaker and media demagogue. Yet in contrast with Raymond’s old guard activism, Branche’s firebrand style promised to reinvigorate Chester’s civil rights struggle. The NAACP feared becoming irrelevant as younger blacks across the United States demanded quicker social change. Regarding Chester, the national office blamed Raymond for improperly handling Branche and not keeping him in the fold of the local chapter. The deputy executive director of the NAACP noted, “Methinks Raymond created a Frankenstein in Branche, let him get out of hand, failed himself to provide aggressive leadership.”

In the remaining months of 1963, the national office pursued two seemingly contradictory solutions to the Branche-Raymond “Chester problem”: to co-opt Branche and bring him and the CFFN back into the fold and to distance itself from Branche by pointing out that the CFFN’s tactics were incompatible with the civil rights cause. In either case, Raymond appeared left out. With the tacit approval of the national office and unbeknownst to Raymond, the NAACP’s regional secretary had supported Branche in organizing the Chester branch’s younger members and forming the CFFN. Upon learning of the NAACP’s role, Raymond protested, “We have an NAACP field secretary forming a new group, further dividing the small army of responsible citizens and the money available—evidently supported by the NAACP.” The national office responded that Branche “has no official capacity at the present time with the NAACP.”22

Branche’s CFFN took on Raymond’s long-term cause: an immediate end to overcrowding and poor conditions at black schools and the larger goal of public school integration. In November 1963 CFFN protesters blocked the entrance of Franklin Elementary and followed with additional protests at the Chester Municipal Building; 240 protesters were arrested. Public attention, stoked by media coverage of the mass arrests, forced the mayor and the school board, in a meeting with Branche and Phillip Savage, the NAACP’s regional director, to agree to make physical improvements at the school and transfer 165 of its students to reduce overcrowding. Encouraged by the successful outcome of Chester’s first mass demonstration, the CFFN took full credit. Branche told the local media “that the Board of Education had given in to many of CFFN’s demands.”23 In light of the successful school protest, Raymond reluctantly invited Branche and Savage to a Chester NAACP branch meeting. Neither man showed up. Instead, a small group of CFFN members still affiliated with the NAACP’s youth organization arrived carrying placards protesting the NAACP’s feeble support of Chester’s awakened civil rights movement. At the meeting one protester asked Raymond if he was tied to Chester’s Republican Party machine.

The CFFN successfully seized control of the school issue, sponsoring boycotts and organizing mass demonstrations against Chester’s segregated schools in the first half of 1964. Mayor Eyre was replaced by James H. Gorbey, who publicly condemned the boycotts and demonstrations and instituted a policy of arresting persons “blocking traffic and entrances to buildings in the course of demonstrations.”24 The stakes became higher in March when the Chester Human Relations Commission formally recommended integration of the elementary school faculties by the next school term and development of a plan for integration of the student bodies. The school board immediately rejected the commission’s recommendation, sticking to its claim that there was nothing it could do about the racial imbalance in the schools caused by the segregation of the city’s neighborhoods.25 Facing public uproar over the board’s refusal to change its policies, Raymond again reached out to Branche to join forces.

Just as the NAACP signed on to the CFFN’s agenda of protesting de facto segregation in public schools, Branche upped the ante by inviting the controversial activist Malcolm X to speak in Chester. On March 11, 1964 Raymond sent a handwritten note to the NAACP deputy executive director reporting on his progress with Branche: “I believe he’s coming back into the fold—some of his group will meet with the Chester NAACP Board tomorrow night.” In a postscript he added, “Provided he cancels Malcolm X.” On March 14 Malcolm X, speaking in Chester, obliquely referenced the CFFN-NAACP split:

We should be peaceful, law-abiding, but the time has come for the American Negro to fight back in self-defense whenever and where ever he is being unjustly and unlawfully attacked. . . . The political philosophy of Black Nationalism means: We must control the politics and the politicians of our community. They must no longer take orders from outside forces. We will organize and sweep out of office all Negro politicians who are puppets for the outside forces. Whites can help us, but they can’t join us. There can be no black-white unity until there is first some black unity.26

Raymond immediately issued a statement distancing the NAACP from Malcolm X’s visit, Branche, and the CFFN: “The Chester NAACP does not endorse Malcolm X nor those groups and individuals who tacitly or openly support him.”27 Raymond was quoted in the local press as saying, “Malcolm X’s statements regarding violence are not only incompatible with the program of the NAACP but are designed to create an aura of suspicion and misapprehension among white persons regarding peaceful and lawful demonstrations sponsored by legitimate and established civil rights groups.”28

A dozen church ministers telegrammed the national office in anger over the NAACP-CFFN alliance. In response, the NAACP promised to end its ties with Branche and the CFFN unless both “completely disavow their association with Malcolm X and the philosophy he represents.”29 At the same time, the national office continued to pressure the Chester branch to endorse and participate in CFFN-sponsored mass demonstrations or risk being left behind and becoming irrelevant to the next generation of activists. Branche’s contact in the NAACP convinced him to issue a short declaration stating that Malcolm X’s appearance at a “multi-sponsored meeting does not imply an endorsement of his principles.”30

Civil rights leaders Lawrence Landry (SNIC-Chicago), Gloria Richardson (Cambridge, Md.), Comedian Dick Gregory, Malcolm X (New York City), and Stanley Branche (Chester). March 14, 1964, Chester, Pa.

In the first half of 1964 Branche offered Chester a novel brand of civil rights activism that generated a great deal of press attention, deep controversy within the black community, and tensions between the local and the national NAACP leaderships. Branche routinely and provocatively railed against the school board, the police department, and the Republican political machine, generating headlines and undoing Raymond’s legacy of quiet pressure and patient tenacity. In a city systematically governed for generations by institutions anchored in securing white privilege, Branche’s radicalism appealed to many local blacks and shocked and angered whites and conservative blacks. For Branche’s expanding numbers of supporters, months of mass demonstrations and protests meant risking life and limb to undo once and for all the city’s legacy of deep-seated racism. For Raymond, Barbour, and other Old Guard activists, the risk of backlash from the political establishment was matched only by their ongoing suspicion and apprehension of the larger-than-life Branche.

Raising the Stakes of Civil Rights Activism in 1964

Emboldened by the Franklin Elementary School demonstrations, the CFFN recruited new members and began to plan its next moves. In January 1964 the organization opened a storefront recruitment center, sponsored a voter registration campaign, and prepared for a scheduled citywide boycott of Chester’s public schools.31 By spring the CFFN leadership and the Chester police were embroiled in a tit-for-tat struggle over demonstrator tactics and law enforcement response, each ratcheting up the stakes. Ultimately, the police violently cracked down on civil disobedience.

As CFFN leader, Branche planned and directly coordinated a combination of marches, sit-ins, boycotts, and mass demonstrations at targeted institutions (mainly schools and city hall) and commercial streets in the central business district. Throughout the spring unrest, Branche acted as press spokesperson, community liaison, recruiter, and chief negotiator. He nurtured ties with student groups at Pennsylvania Military College, Swarthmore College, and Cheyney State College to ensure large turnouts at marches and demonstrations.32 With few exceptions, the direct action campaigns were large in numbers; frequent (eventually daily); and disruptive to business, government functions, and pedestrian and vehicular traffic.33 On March 27, for example, three hundred protesters marched from a church rally in the West End to the downtown business district escorted by the entire Chester police force of seventy officers. Police arrested three protesters for impeding traffic, prompting all the remaining demonstrators to sit down at a busy shopping intersection. The protesters dispersed after Branche received a tip that sixty Pennsylvania state troopers had been called as backup.34 On the next day the CFFN staged simultaneous midday sit-down demonstrations to intentionally shut down traffic in downtown Chester. Over two hundred protesters assembled in front of the CFFN office, where they were instructed to march together downtown, disperse into small groups, sit in key intersections, sing and clap, and “play dead” if confronted and arrested by the police. The multiple sit-down tactic worked. Downtown traffic came to a standstill, and dozens of white office workers, sales clerks, and curious shoppers lined the sidewalks to gawk at protesters. The police response was swift and violent. On March 28 the Delaware County Daily Times described the incident at Seventh and Edgemont Streets: “Club-swinging city police halted a racial sit-down at the busiest intersection in the city this afternoon.” On March 30 the same paper said that on March 28 police had “moved in, swinging riot sticks.” All the protesters were arrested.35

Protesters responded to the violent crackdown by the police with even larger demonstrations. Ordinary Chester citizens, outraged by the images of passive demonstrators beaten with nightsticks and dragged off to waiting buses, filled the streets to oppose the escalation of police violence. The atmosphere downtown became so tense that the anticipated nightly standoffs between police and protesters overshadowed the original objectives of the demonstrations. Branche took to the airwaves, calling for massive civil disobedience to the police response. The demonstrations grew larger, with an estimated three hundred and fifty persons marching into the center of the city and around the police station on April 2. That day Mayor Gorbey issued “The Police Position to Preserve the Public Peace,” a ten-point statement promising an immediate return to “law and order.”36 The city deputized firemen and trash collectors to handle demonstrators. The mayor formally requested the assistance of the state police. April witnessed successive nights with hundreds of demonstrators arrested and dozens beaten. All Chester’s public schools closed on April 22 amid fears for student safety. With no end in sight, Mayor Gorbey spoke to the slim chance of a negotiated truce: “There’s only one man out there and that’s Stanley Branche that could get them to declare a moratorium [on demonstrations]. And I don’t believe that I could be the person to ask him.”

Police retribution climaxed late in the evening of April 22, a night of brutality that a commission appointed by the governor later called “the straw that broke the camel’s back.” That evening Chester police and eighty Pennsylvania State Police troopers surprised a group of three hundred protesters who rallied at the police station. A small cadre of Chester police officers demanded that demonstrators stop singing and disperse or face arrest. Some protesters dispersed, but others began to march until the police physically blocked them. About forty Chester police officers and the state troopers “came in a group with a great rush out of the police station” to disperse the demonstrators.37 Dozens were beaten. At a mass rally against police brutality two nights later, more violence ensued, as the state police again assisted in forcibly dispersing protesters. That night a large number of state police officers burst into the Bull Moose Bar at Third and Lamokin Streets around midnight and “surrounded, cursed, and indiscriminately beat the male and female occupants.”38 On the night of Saturday, April 25 there was “so much tension in Chester that one hardly dared light a match.”39 Only the governor’s intervention on April 26 prevented a “grave race war.”40 Altogether, over six hundred people had been arrested during approximately two months of civil rights rallies, marches, pickets, boycotts, and sit-ins.41

Understanding the “Chester Situation”

The protests of 1964 energized the local struggle against entrenched racial segregation in Chester. The sheer number of local residents, the commitment to a costly and unrelenting campaign, and the consistent threat and frequent occurrence of intimidation and physical violence upended the old order that had defined the city’s history for decades. Given the degree of the local white political establishment’s commitment to racial inequality across employment, housing, education, and everyday activities, the civil rights movement in Chester was clearly an accomplishment, especially for the individual women, men, and children who vowed to bring about real change.

In the weeks following the April unrest, the CFFN collected dozens of statements from protesters who suffered or witnessed excessive use of force by police on April 22 and April 24 and presented them to the Human Relations Commission.42 Although the commission was highly critical of civil rights leaders for calling for continuous demonstrations and considered the sit-ins illegal, it did find in favor of the protesters: “There is reason to believe that the political ‘power structure’ was unsympathetic with the immediacy of demands of the Negro community and that this attitude was to some extent reflected in the methods adopted by the police to repress the demonstrations.”43

The Chester demonstrations also prompted the state to take action on long-standing racial problems. At a meeting in Philadelphia with the state attorney general, the mayor of Chester, the city solicitor, and representatives of the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, Governor William Scranton ordered public hearings on the charges of de facto segregation in Chester schools.44 While the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission held hearings during the summer of 1964, all protests and demonstrations ceased. In November the commission issued its final order requiring the desegregation of schools and an end to the practice of assigning only black teachers, stenographers, clerks, and bookkeepers to predominantly black schools. The commission found that although the Chester School Board was “aware or should have been aware of the existence of segregated schools within its system, it did not act at any time to attempt to correct this condition.”45 The school district appealed the ruling and the commonwealth court partially ruled in the district’s favor, stating that the commission did not substantiate its charges of intentional segregation. The court did uphold the commission’s ruling on faculty placements. Through appeals, the commission and the school district took the case to the state supreme court, which upheld the findings in September 1967. Most of the recommendations remained unfulfilled through the 1970s, as the commission had limited authority to enforce them.

Governor Scranton also supported the formation of an umbrella organization to solicit grassroots participation of resident constituents to reduce the immediate racial tensions in the aftermath of the demonstrations. The Greater Chester Movement (GCM) was formed with a mandate to unify and coordinate the efforts of existing government agencies and community organizations, including civil rights groups. The CFFN referred to the GCM as “a much needed moral face-lift after the city’s real face was unmasked to reveal its grotesque features, distorted by injustice, bigotry, and decadence.”46 Branche was appointed the GCM’s director of operations in 1965.

The mass protests and demonstrations of the civil rights movement came relatively early to Chester, prompting considerable attention from the national media and other activist organizations. For certain, Chester was not the only northern city to experience the sustained mass demonstrations, racial unrest, and police violence that accompanied the civil rights activism in the 1960s. Nor was it the only city where the debate over strategies and tactics split local organizations. That the 1964 protest campaign produced political and organizational costs for the local civil rights movement is to be expected. But in line with this book’s argument that local power holders manipulate racial issues to effect changes for their own benefit, it is worth examining whether and to what degree those costs were influenced by the actions of Chester’s white political establishment. The historical record points to questions about the relationship between Chester’s political establishment and the CFFN during the protests of 1964 and immediately thereafter regarding the adoption of direct action as the key movement strategy, the extent of the tactics deployed, and the role of the CFFN leader Branche. Each of these points is taken in turn.

For the Old Guard activists Barbour and Raymond, the strategies adopted by Branche’s CFFN meant the abandonment of legal efforts to use the courts to push desegregation or enforce desegregation orders. Barbour in particular considered it foolhardy to write off all whites as the opposition and continuously clamored for working with sympathetic whites to improve the civil rights situation.47 Clearly, boycotts and sustained mass protests grabbed newspaper headlines and kept public attention focused on the issue of school desegregation. Few disputed the importance of such attention, but NAACP leaders, including leaders at the national office, questioned the practical implications of nightly protests and mass arrests. “The persistence of the demonstrations seems in part to have been designed to harass the police and to exploit a heightening emotional tension.”48 Old Guard leaders were puzzled and bothered by the CFFN’s lack of an endgame or exit strategy. Branche fired up the young black population with demonstrations, pickets, and boycotts, but he offered few details about the movement’s goals. Some repudiated their decades-long association, writing to the national NAACP in the heat of the unrest in March 1964 that they “[found] it impossible to accept the kind of leadership being manifested now and which has taken over this campaign.”49 Even Savage, the regional director who had once courted Branche and supported the CFFN, complained of Branche’s uncompromising, if not outright obstructionist, attitude toward working with the NAACP or the Chester Human Relations Commission.

Branche engaged in one-upmanship with the established civil rights organizations in the community, boasting that the CFFN was the only true civil rights force in Chester. He cut the lines of communication with mediators and go-betweens in the white community. In open meetings that the press attended, he was prone to give ultimatums to city and school board officials, such as “do-or-die” deadlines for meeting demands. When the ultimatums were rejected or deemed impossible to satisfy, he walked out, held an impromptu press conference, and strongly condemned the other party. Such actions made a settlement of the school crisis that was agreeable to both blacks and whites less likely. In late March 1964 the school board accepted the Chester Human Relations Commission’s call for a study of the feasibility of one large, central school to eliminate de facto segregation. The CFFN refused, insisting that the black leaders who would participate in the study no longer represented Chester’s black community.50 In April Branche announced that he would no longer deal with the Chester Human Relations Commission and would only meet directly with the entire school board. Mayor Gorbey arranged a meeting with Branche, the school board, and the white Chester Parents Association (CPA). Upon learning of the CPA’s planned appearance at the meeting, Branche refused to attend.51

It is no surprise that the civil unrest of 1964 did not sit well with the majority of Chester and Delaware County whites. Angered by the costs of disruptions, downtown store owners and businesspeople pressed city hall with demands for restoration of law and order and welcomed the mass arrest of protesters. White customers opted to shop elsewhere. As the protests wore on and grew larger and the police response grew more aggressive, white residents feared the immediate and long-term repercussions of the end of their privileged place in the racial status quo. Parents demanded police protection of public schools and their mounting fears influenced the school board’s decision to close all schools in April. The protests hardened the resolve of those committed to segregation. The CPA was formed after the November 1963 action at Franklin Elementary School and had grown to thirty-four hundred members by May 1964. “It was obvious that many white parents in Chester are deeply troubled by the new militancy of the city’s Negro citizens and fearful that their children will be sent to strange schools in strange neighborhoods.”52 Those who could afford to do so transferred their children to parochial and private schools. Many expressed frustration with the city leaders’ inability or unwillingness to end the unrest. Feeling abandoned by a political machine that had long preserved white privilege, hundreds left the city for the suburbs, where they were warmly welcomed (ironically) by the same political machine.

Not all white residents opposed the racial integration of public schools and an end to the social and political exclusion of Chester’s black community. Many whites expressed an interest in working with black leaders either for reasons of social justice or pure pragmatism. But the NAACP-CFFN rift and the intransigence of Branche rendered cooperation among blacks and whites difficult. Branche canceled a number of planned meetings between CFFN leaders, the Chester Human Relations Commission, and the Chester School Board, prompting more protests and rallies. The Delaware County commissioners tried to organize a meeting with Chester city officials, the Chester School Board, the NAACP and CFFN leaders, and representatives of state and local human relations agencies. But the CFFN carried out a series of demonstrations at several Chester schools and public buildings the same day, prompting the school board to close all eighteen of Chester’s public schools.53

The Chester School Board finally accepted a legal hearing—as Barbour and others prescribed—to allow a court to determine its role in ending de facto racial segregation, but complained of a lack of a single authoritative voice in the black community. At a meeting on April 17, 1964 Guy De Furia, the counsel for the school board, stated, “It’s difficult for me to believe that the NAACP, an organization of that standard, refuses to go into court in a matter like this and would prefer to create turmoil and disorder in our city.”54 But the NAACP was powerless to do so. Branche’s approach favored an end to communication with the white community. In April 1964 the question was posed at a board meeting: “Is there any responsible group who speaks for the Negro community? Who is the plaintiff in the court here? And I can’t see any distinguishable, responsible group that anybody can deal with.”55 Conservative elements in the black civil rights movement questioned whether the strategy of direct action and official disengagement played into the hands of Republican politicians, a point noted by the Pennsylvania Human Rights Commission.

The two issues mentioned above would have amounted to very little but for the final, most important concern that Chester’s civil rights community voiced—that of Branche’s central role. In spite of the rankling within the NAACP and complaints about the CFFN leader’s tactics and motivations, observers at the time conceded that nothing much would have happened in the Chester civil rights movement without Branche. But Branche had not created the conditions that brought thousands of Chester’s black residents to the streets in protest; their discontent was decades in the making. Nor was he responsible for the growing unease and increased fear of whites over the impending demise (and comfort) of the city’s racial status quo. The departure of whites for the suburbs may have accelerated after the unrest of 1964, but it had begun in earnest a decade earlier. But Branche was clearly a catalyst of events that led to significant changes in the black-white divide and the spatial order that upheld it. Even Raymond conceded, “We needed Stanley to light the fuse.”56

During the summer of 1964, during the state Human Relations Commission’s open hearings on Chester’s school segregation, details about Branche’s connections to the Republican machine began to emerge. Branche, it turns out, had spent some time in Chester prior to his reported arrival in 1962. In the spring of 1955 a Republican city councilman convinced him to work on an upcoming mayoral election. When he reappeared in Chester in 1962, it was widely reported that Branche became involved in the local civil rights struggle after his wife Ann Branche introduced him to Raymond. His wife had been raised in Chester by her aunt and uncle, the latter a prominent black lieutenant in McClure’s Republican Party. Along the way to becoming the city’s main civil rights leader, Stanley Branche had “cultivated a supposedly close friendship” with a local Republican magistrate. Through his earlier contacts with civil rights leaders in Maryland, Branche had become acquainted with Attorney General Robert Kennedy. In 1963 he accompanied the Republican Gorbey (who became Chester’s mayor in 1964) to Kennedy’s office to discuss Gorbey’s possible appointment to a federal judgeship (it did not happen). The state Human Relations Commission heard testimony from McClure’s operative at Sun Ship responsible for assisting the Pews’ antiunionization efforts in the mid-1940s.57 The commission learned that Branche was a “McClure plant” intentionally sent to infiltrate Chester’s civil rights movement—not to uncover information (a network of machine lieutenants could easily have accomplished that) but for something far more nefarious: to stir up black discontent and instigate civil unrest that would provoke reaction from the white community. Apparently, McClure calculated that even Democrats fearful of urban unrest would flock to Republican candidates on Election Day. That failed to happen.58 Raymond—who had long suspected that Branche was a McClure operative who routinely communicated details about civil right activities to machine officials—felt vindicated by such claims.59

With his appointment as director of operations with the GCM, suspicions regarding Branche’s role in the civil rights unrest of 1964 and his motivations as an activist gathered further momentum. That appointment revealed the extent and depth of his connection to the Republican political machine. His former CFFN associates balked at his new position, calling his appointment an “insult to the Negro community and the Chester population at large.”60 “Many Negroes are wondering,” penned a letter writer to the local newspaper, “if there are any ‘power structure strings’ attached to Stanley Branche’s lucrative GCM salary.”61

Branche once again resurfaced as an activist in the civil rights struggle in 1968, this time in Philadelphia, where he sided with the more radical elements in the Black Coalition, a short-lived multiracial action group formed in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. In the summer of 1968 the coalition sponsored dozens of large and small programs in Philadelphia’s black neighborhoods, including reading programs, sports leagues, college placements, big sisters, and a children’s aid society. Branche was appointed executive director, and from his West Philadelphia storefront office he spearheaded an adult job placement program that showed initial success in matching applicants with employers. His fiery rhetoric immediately won over many young followers and he did much to defuse tensions surrounding the Black Panthers convention held in the city in September 1968. But Branche’s motives and leadership skills were soon questioned. The coalition grew alarmed at his ability to spend large sums of money and his lack of bill paying and financial record keeping. His appointment was terminated and the coalition disbanded in the fall of 1968.62

Whether or not McClure was directly responsible for stoking the embers of racial unrest, his political machine clearly benefited from its consequences. The spring of 1964 highlighted the differences between the city and its suburbs for Chester’s whites who were still on the fence, considering a move. McClure and the Republican machine had already quietly constructed the political and economic supremacy of the suburbs, and the white exodus would only further consolidate the machine’s power. McClure may have planted the activist Branche, but he commanded neither the sequence of events of 1964 nor the sense of grassroots achievement among black residents long silenced by the political workings of the machine.

McClure died on March 28, 1965. Whether or not he had intended to perpetrate race-baiting on such an organized and massive scale might never be fully known, but the answer is perhaps less important than the fact that his successors clearly capitalized on ensuing racial fears to further isolate Chester from the rest of the increasingly wealthy Delaware County. Thereafter many whites viewed Chester as a place of hostility and potential danger and a place to avoid.

An Opportunity to Move Forward: The Greater Chester Movement

Governor Scranton’s direct intervention in the Chester crisis marked a pivotal turning point in the local civil rights movement. The timing of Scranton’s commitment to address racism and poverty—especially his support for the GCM—coincided with the rollout of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty initiatives. The passage of the federal antipoverty Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 permitted cities to plan and implement comprehensive and coordinated approaches to solving pockets of entrenched poverty, such as black inner-city communities impoverished by various and lasting forms of institutional discrimination. In August 1964 the federal Office of Economic Opportunity designated the GCM as the Committee Action Agency in Delaware County to administer Johnson’s War on Poverty programs.

The founding of the GCM in the wake of the unrest of 1964 provided a rare chance for local organizations to tap directly into emerging federal and state programs for poverty relief. The promise of the War on Poverty for grassroots change should not be underestimated. For the first time, the supremacy of Chester’s local Republican machine politics could be bypassed. The GCM’s core mission was to coordinate existing social services and determine means for delivery to the poorest residents at the block level.63 Several mechanisms were designed to link agencies with residents. First, the organization formally networked with existing civil rights groups in Chester, including the NAACP, the local branch of CORE, the CFFN, the West End Minister’s Fellowship, the Young Adult Council, and the Chester Civil Rights Committee. The GCM also created new block-level organizations and developed leadership training at the neighborhood level. Second, the city’s poorest areas were divided into five geographic areas, each with its own social services coordinator who supervised block captains (four to each area) with direct links to residents. Coordinators worked with block captains to implement Community Action Projects centered on jobs, housing, and education. They organized volunteer work crews to paint houses, repair masonry, and fix or replace windows. In addition, the GCM opened Neighborhood Action Centers (NACs), storefront offices that functioned as a “casual drop-in center, handy, unpretentious, deliberately eschewing an air of officialdom, a bridge between the poor and existing aid programs.”64 NACs were intended as informal spaces that would build trust and “intimate rapport” between poor people and social service providers and government agencies. The staff served both as agents of city and county social services and as advocates for residents, “thereby increasing democratic participation in community government.”65 NACs organized meetings; programs on housing, credit unions, consumer cooperatives, employment, and business development; and elderly and youth programs.66

In 1965 the GCM received $1.5 million in funding from the federal government for the Jobs Corps program that led to the opening of the city’s Opportunity Center, a combined educational and job skills training facility. The Adult Education and Vocational Education Divisions of the Chester School District also expanded their offerings through the GCM. Numerous occupational training courses, most of which were funded under the Manpower Development and Training Act, were offered through a cooperative program with the Pennsylvania State Employment Service.67 The early efforts paid off. The GCM developed youth services and job programs with the help of General Electric, Scott Paper, and other local corporations.68 The ability to keep a lid on further social unrest was attributed to the GCM as its most notable accomplishment.

Initially, the GMC appeared to offer Chester’s poor minority residents a stake in grassroots political input, a means toward racial progress, and a path toward the alleviation of poverty. Such meaningful efforts at social change were short-lived, however. Its undoing was caused by a mix of national politics and inexorable pressures from Chester and Delaware County politicians to exert control. The GCM was one of hundreds of community action agencies tied to Johnson’s War on Poverty. State and local social service programs worked directly with community activist organizations in poor minority districts in Philadelphia, New York, Cleveland, Buffalo, and many other cities, as statutorily required by federal policies aimed at maximizing representation and participation from the residents of affected communities. Federal antipoverty initiatives assumed that local institutions would have the motivation and capacity to design, support, and implement the necessary antipoverty programs. However, the grassroots response was not matched by an appropriate level of federal funding or oversight.69 Many programs, including the GCM, were quickly beleaguered by the scope of community problems, lack of expertise, and overtaxed budgets.70

Within a year of its founding, the GCM was effectively hijacked by the Delaware County Republican political machine, which saw the organization as an easy front to funnel federal dollars into the pockets of political operatives. The GCM had sought to tap into leadership in the black community outside the influence of Chester politics, but local politics proved too resilient. The machine cleverly usurped the GCM’s mission and provided “expertise” for managing the War on Poverty. The GCM’s grassroots origins faded and block-level volunteers with direct access to their neighbors were distanced from policy making. As the next chapter details, the GCM became one of several institutional mechanisms implicated in the establishment of a parasitic economy in the inner city.

From Containment to Fear

In the early 1960s the strategic employment of race in Chester transitioned. At the start of the decade, the racial social and spatial order in which blacks were separately and unequally contained was already under pressure from demographic and economic changes enveloping the region. By the close of 1964 the framing of the racial divide by whites and white institutions had shifted toward a focus on the menace posed by black efforts toward social justice. This new narrative of the ghetto as a threatening space to be feared by whites proved useful to local stakeholders in urban change for decades to come.

The repeated standard history of the civil rights movement rightfully emphasizes the struggle of black Americans for equal treatment and fair access to social, political, and economic opportunities. The Chester story is no different. However, the collective endeavors of the city’s poor and disenfranchised inspired a perverse secondary function that facilitated urban changes benefiting those with capital, power, and privilege. This second, duplicitous function, based entirely on deception and the raw abuse of power, by no means detracts from the significance and meaning of mobilization and resistance for the thousands of Chester residents who participated in protests and demonstrations. But it is a clear, albeit unusual, example of how misshapen ideas and accepted wisdom of the racial divide enabled and arguably accelerated urban transformation. For many whites, the civil unrest of 1964 solidified the suburban option as not only ideal, but as a solution that was urgently necessary and incriminated the city as a space to fear.

For a city suffering from the consequences of entrenched institutionalized racism, the founding of the GCM afforded an opportunity as a truly grassroots force for social change. The opportunity was squandered. Under the guise of providing assistance to the city’s poor and addressing patterns of racial discrimination, the Delaware County political machine marshaled its network of resources to transform the GCM into a money-peddling enterprise rewarding faithful political operatives. The GCM’s origin as a grassroots solution to racial discrimination provided racial cover for a new, post–civil rights local politics of disinvestment and extraction of urban resources. As the following chapter details, the pilfering of the GCM was the first of several incidences in which local elites used the prevailing rhetoric of race and racism as a means to profit from and reinforce control over poor minorities. The result was more of the same—disappointment and fatalism among Chester’s dwindling population.