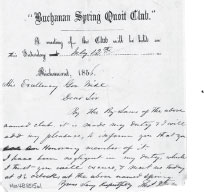

An engraving of Englishmen throwing quoits at megs. Visit the John Marshall House to give the chief justice’s favorite game a try. Virginia Cavalcade, Library of Virginia.

BUCHANAN BARBECUES

Jasper Crouch and John Marshall

Some of the most memorable feasts of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in Richmond were concocted by a caterer and majordomo in demand, Jasper Crouch, a free black man, at the bucolic setting of Buchanan’s Spring, just outside the city, where Hancock and West Broad Streets are now. The spot’s simple pleasures included large oak trees to provide shade, an open-air shed with a large wooden table underneath for the ample meals and a clear stream flowing through the property, which had been inherited by a much esteemed Episcopal priest, the Reverend John Buchanan.

GETTING PUNCHY

The Richmond Light Infantry Blues, the second-oldest volunteer militia in the nation, founded in 1789, held festivities at Buchanan’s Spring through the generosity of Buchanan, and they routinely enlisted Crouch to attend to their massive meals after parading and drilling. Crouch was a believer in pork heavily seasoned with cayenne pepper, among other specialties. Besides knowing his way around roasting a pig, Crouch distinguished himself further with his concoctions of punches and mint juleps that filled the massive, thirty-two-gallon India china punch bowl the Richmond Blues proudly set out at every celebration. His bartender chops gave the punch some serious punch.45 And since a typical Richmond Blues July Fourth celebration at Buchanan Spring included dozens of toasts to the Revolution, to Washington, Lafayette and on and on, it’s easy to imagine more than a few gentlemen punch-drunk by mid-meal. As the Genius of Liberty reported in 1826, the “Richmond L.I. Blues, with their guests, dined, as usual, at Buchanan Springs when the following toasts were drank with great hilarity and good feeling. The Spirit of ’76—The electric flash, which purifies, while it enlightens.” The toasts continued, so much so that the Richmond Enquirer’s sub headline, “Drunk at Buchanan Springs,” makes perfect sense.

Crouch’s prowess with the pig and the punch bowl caught the favor of another group of gentlemen who started their own social club in the late 1780s, including John Marshall, who later became chief justice of the United States and lived in Richmond throughout his thirty-four-year tenure on the court. The club’s origins harken back to Scottish merchants in Richmond looking to gather a group of no more than twenty-five men for a simple meal every other Saturday from May until October under the auspices of the Amicable Society of Richmond. The original plan was simple enough, with “some cold meats for their repast, and to provide a due quantity of drinkables and enjoy relaxation in that way after the labors of the week.” They limited expenses by initially outlawing wine and porter at their gatherings.46 That didn’t last long.

An engraving of Englishmen throwing quoits at megs. Visit the John Marshall House to give the chief justice’s favorite game a try. Virginia Cavalcade, Library of Virginia.

By February 1801, the club had changed its name to the Buchanan Spring Quoit Club and made Buchanan its president, which made sense, since his hospitality allowed them their literal country club. With room to roam, they were better able to indulge in the popular game of quoits, a game brought over from England, similar to horseshoes. Two teams pitched quoits, circular rings made of brass or iron, onto (they hoped) stakes, called megs, in the ground. Marshall was a quoits aficionado, so he usually headed one team while the Reverend John D. Blair led the other. Games took place on both sides of the ample meal, and Crouch was the keeper of the rings, polishing the brass ones most members used and keeping Marshall’s preferred heavy iron rings at the ready. Marshall was competitive enough that he was known to get down on his knees to measure the distance between quoits to determine the winning team.47

THE MEAL’S THE THING

Procuring the best ingredients to make a sumptuous meal was as competitive as the quoits. At each meeting, two members were assigned to act as caterer, which meant going to either Old Market on Main or New Market on what’s now Marshall Street to buy the goods, staying within the club allotment. Here’s just some of what $46.60 bought for a Quoit Club gathering in 1838: “A pig, 47 lbs of mutton, 15 lbs beef, 18 lbs sturgeon, 12 chickens, 2 large hams, 1.5 gallons brandy, 1.5 gallons rum, .5 whiskey, 12 bottles of porter and 1 pint of wine.” Vegetables included potatoes, beets and cucumbers, and seasonings included cayenne pepper, mint and sugar. Lemon, eggs, butter, cheese and more rounded out the order.48

It was then up to Crouch to take the purchased goods and turn them into a celebratory and sumptuous meal. For his services, Crouch charged three dollars to butler and supervise the event, bringing his cart to take the supplies to the springs, providing ice and firewood there and paying cooks and servants.49

Watching the cooking was part of the entertainment of the day for the attendees. One visitor remarked that the roasting utilized the Indian method of cooking that John Smith had seen centuries before: a fire going underneath a platform made by four stakes with sticks across. Roasted pig was the main course of Quoit Club so often that the club’s nickname was Barbecue Club. But there were many delights served at the table. One member recalled “deviled ham, highly seasoned with mustard, cayenne pepper, and a slight flavoring of Worcester sauce.”50 And years later, “Colonel Ellis wistfully recalled that he had never again eaten sturgeon cutlets to equal those prepared for the club.”51

A RULING FROM THE CHIEF JUSTICE

Quoit Club members included such luminaries as attorney John Wickham, who defended Aaron Burr in the trial of the century; president of the Bank of Virginia John Brockenbrough; physicians; military men; and merchants. The current governor of Virginia was an honorary member, and before each meeting, members called at the finer hotels to see if any worthy visitors might lend their wit to the event. General Winfield Scott was a regular attendee. In perhaps a stroke of genius, the rules included a prohibition on talking politics. The fine for flouting that rule was one basket of champagne brought to the meeting. On at least one occasion, Chief Justice Marshall ruled against the guilty parties, and the offenders produced the bubbly, though it had to be drunk from tumblers, as champagne glasses were not on site.52

It’s likely that when John Marshall was the member in charge of the fête, he made sure some of his beloved Madeira made its way into Crouch’s concoction for the quintessential Quoit Club Punch. An old recipe calls for “lemons, brandy, rum and madeira, poured into a bowl 1/3 full of ice (no water) and sweetened.”53

Crouch’s mint juleps were worthy as well. One visitor, Chester Harding, a portraitist in town to paint John Marshall, was invited to attend Quoit Club in 1826. As he tells it:

I watched for the coming of the old chief. He soon approached with his coat on his arm, and his hat in his hand, which he was using as a fan. He walked directly up to a large bowl of mint-julep, which had been prepared, and drank off a tumbler full of the liquid, smacked his lips, and then turned to the company, with a cheerful, “How are you, gentlemen?” 54

A coveted invitation to the Buchanan Spring Quoit Club at 2:00 p.m., July 12, 1856, from Thomas Taylor to Henry Alexander Wise. MSS 4 B8515, Virginia Historical Society.

Crouch continued as a caterer and restaurateur until his death, when he was buried with full military honors by the Richmond Light Infantry Blues, such was their appreciation for his contributions to their celebrations over the decades.

It’s possible to toast Crouch and this chapter in Richmond’s history by taking a tumbler of barman Thomas Leggett’s version of Quoit Club Punch at The Roosevelt on Church Hill. Or you can refer to his recipe in chapter 24, which is adapted from Dave Wondrich’s recipe, which was adapted from the recipe above, which is as close as we’ll ever get to the original.

The throwing of large metal rings after imbibing is optional.