Jennifer Steinkamp

Breathing in the World

You can’t fly if you don’t have the hardware,

You just hang there like a heart on a wall.

—Jimmy Destri

In the chaotic narratives of art and culture, there are always jobs left undone and promises unkept. Every age presents its artists with possibilities that, for reasons of fashion or technology, cannot be realized when they present themselves. In any age, there is a logic of practice and stylistic continuation from which we may infer new resolutions that cannot be articulated with the materials at hand. Usually, when this happens, attention wavers, the runner stumbles, the torch falls, flickers, and goes out. The world moves on to more modest and achievable options. The possibility does not die, however. It remains, redolent with potential, in the historical objects and the practices that originally created it. It waits for the moment when it becomes doable—and for the moment that it needs to be done. Some tasks wait forever, but sometimes the original runner picks up the torch again, as Frank Gehry did when he produced the Guggenheim at Bilbao and gave form to a vision that was conceptually and aesthetically available in 1972, even though it was technologically impossible and wildly incongruous with those darkening times. Sometimes a younger runner, sensing the vacancy and the need, grabs the torch, relights it, and runs with it. Suddenly the promise and the conditions of the old vision are new and available again.

This is the case with the work of Jennifer Steinkamp. Early in her career, she perceived, in the untethered ambition and slightly demented optimism of “1960s structuralist cinema,” a job that needed to be done and that finally could be done, twenty years after what Gene Youngblood refers to as the paleocybernetic moment. Most critically, Steinkamp found a job she wanted to do and instinctively made an artistic choice to set off like Gauguin to her own technological Tahiti. To escape the tyranny of contemporary fashion and ideology and to see the world clearly, she relocated her practice to the most unfashionable position imaginable. From this vantage point, the chains of fashion and the intellectual mindset are all too visible and a new future is readily available. One proceeds from there.

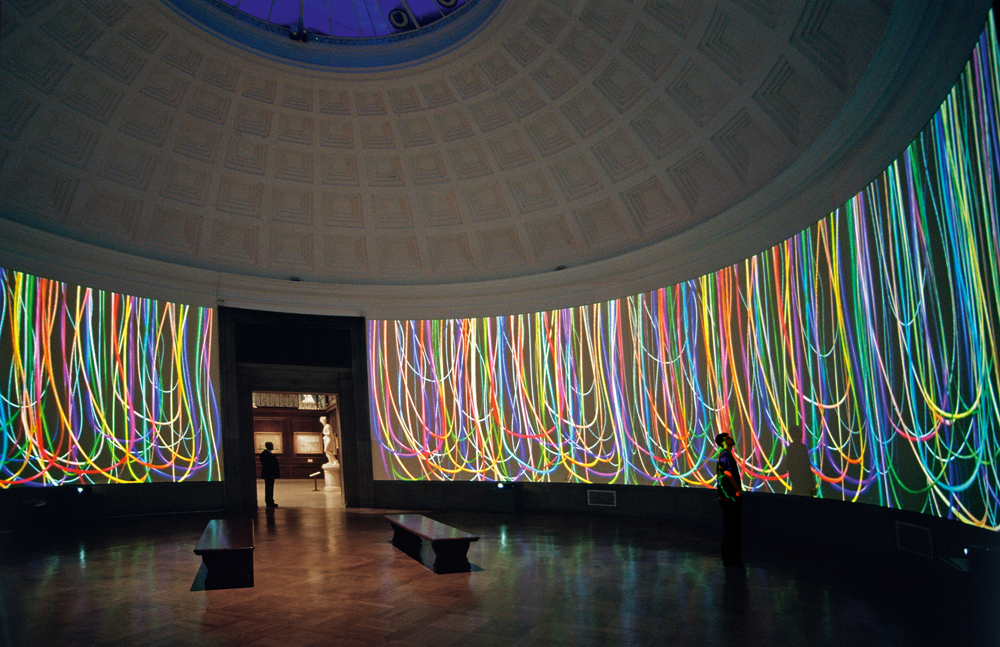

Jennifer Steinkamp, Loop, 2000. Six-channel video projection, 13.5 ft. high. Composer: Jimmy Johnson. Photo: Jennifer Steinkamp. Part of the Collection: The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Courtesy of The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; ACME, Los Angeles; greengrassi, London; and Lehmann Maupin, New York and Hong Kong.

So Jennifer Steinkamp decamped to her technological Tahiti. She set up shop in what was, in the 1980s, a lost world—a terrain so remote from the art politics of the time that it didn’t even tick on the meter. And it was all hers: the detritus and fringe atmospheres of the late 1960s techno: the punch cards and Stone Age computer languages, the subculture of acid-dropping science geeks and techno-cosmic weirdos, the rigorous ephemera of Michael Snow, Robert Whitman, Jordan Belson, and Stan Brakhage, the secrets of the old Jewish dudes who animated Fantasia and the proto-hackers who designed Kubrick’s 2001, the strobe-lit Warholians at the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, and the stoner wizards at the Fillmore who concocted oceanic lava flows of light that spilled out, over, and around the Allman Brothers. Needless to say, setting off like this was a brave choice for a young artist in the 1980s, but it was a very, very good one. In an act equivalent to Mary Heilmann embracing painting at its nadir, Steinkamp embraced structuralist cinema at the apex of its obscurity. She removed herself quite literally to the primal site, flung herself into the turbulent soup out of which arose the lineaments of postindustrial digital culture—the world we live in.

As an additional bonus, Steinkamp found herself in a lost art world whose base presumption challenged the most cherished bits of art theology in the 1980s. At that time, for instance, it was widely presumed that, since “history” died in the late 1960s, innovation and the idea of the “new” had died with it. History, it was said, would soon be replaced with a “thick sociological discourse” of personal narratives—his-stories and her-stories—as if Foucault had never laid bare the mindless solipsism of sociology—as if Derrida had never named language a shared prosthetic. The adepts of structuralist cinema agreed that history was dying all around them, but they also knew that time and complex causation were not dying. Nor was genetics. Time goes on, consequences proliferate, as does artistic practice. So innovation is always required. There is no way to do without the new. The alternative is ennui and entropy, and the world in the wake of history is, after all, a new world (and newer than any of them imagined). Moreover, this new world is grounded absolutely, if paradoxically, in the languages of abstraction—in statistics, cybernetics, dynamic systems, and genetics—so discussion in the structuralist conclaves within which I grew up and which Jennifer Steinkamp has happily revived, was never about abolishing abstraction. It was always about keeping it sexy. We worried, and Susan Sontag worried too, about the erotics and ethics of form, the aesthetics of clouds, the allure of liquid dynamics, the beguiling appeal of “pied beauty”—the chemistry of everything that is haptic, fractal, tactile, restless, and multihued.

The art theology of the 1980s, of course, held that abstraction, and abstract art particularly, was an elitist enterprise best avoided by progressive youth. A twenty-minute visit to the early 1970s would have proved just the reverse. At the Fillmore or in the Inevitable, at Paraphernalia (besieged by super-graphics) or listening to Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music, hanging with Billy Klüver at MIT or goofing in an acid lab, watching Laugh-In sound bites or The Steve Allen Show with fake Stella protractors in the background, it was clear enough, at this moment, that Gertrude Stein was right: that abstraction is the American vernacular and fully available to the so-called common man. Around this time, an artist friend of mine, Susan Teagarden, created a large suite of photographs called Proof of Mondrian. The photographs depicted Mondrian’s graphic signature translated to adorn garbage trucks, dry-cleaning establishments, A-line dresses, basketball floors, and other objects of everyday production. She only stopped because she got tired, she said, adding that she could have easily created another large suite called Proof of Jackson Pollock, documenting the numerous instances of casually dripped kitchen enamel as an element of commercial design. My own favorite in this genre is on the front of the Pacific Shores Lounge in Ocean Beach, California.

As Philip Fisher points out in Still the New World, and Jennifer Steinkamp amply demonstrates, abstraction is the base language of democracy. From the Jeffersonian grid to the Nike swoosh, it engages us and unites us at a level of generalization that transcends our differences, and it is this vernacular commonality, I would argue, and not abstraction’s elitist provenance, that created the jihad against abstraction in the art world of the 1970s and 1980s. My position is that pictures divide us, that representations divide us, and for an art world desperately seeking European “distinction,” the photograph proved a happy, frozen redoubt. If this were not the case, the broad positive response to Jennifer Steinkamp’s refined technological inquiries into the “elitist” practice of abstraction and expanded cinema would be all but inexplicable.

In fact the generous response to Steinkamp’s work, within and without the art world, is not inexplicable at all. For the length of her career, Steinkamp has moved along a road that began in the 1960s as an eight-lane freeway, shrunk to a bike path, and finally turns out to have been really going somewhere. Today, Steinkamp fashions the conditions for a very special brand of synoptic and synesthetic experience out of light and motion in real and virtual space; she creates externalized visual fields and weather systems in which one’s consciousness may unself-consciously disport itself. Like the recent work of Frank Gehry, Richard Serra, and Bridget Riley, and the work of younger artists like Jim Isermann and Jorge Pardo, Steinkamp’s work, once again, after a long hiatus, places the mind at work in the body—in a mode of high abstraction that is so totally in the service of the body that the Protestant distinction between them disappears. More to the point, she creates work that is so visually persuasive, so rhetorically acute, that we are happy to ignore the fact that its success proves a lot of us wrong about the primacy of representation.

One might argue, of course, that Steinkamp’s recent forays into skeining flowers and twirling trees constitute a divagation from abstraction into this “discourse of representation,” and these works do represent a divagation. They show us things we recognize and, as such, they may be taken as an inadvertent curtsy to prevailing taste on Steinkamp’s part. The works, however, do not divagate into narrative, realism, or even surrealism. Their motion is still the motion of pattern and cycle. They do not propose a reality superseding the one in which we stand, or suggest any aspiration to verisimilar dominance. Their divagation is into an even more decorous idiom, into the language of the decorative arts, where Steinkamp’s rooms of turbulent flowers and trees constitute a knowing, updated allusion to the tradition of designing interior space with natural iconography that dates back to the high modernist glass fronts and from there back to the rococo. This allusion allows Steinkamp to exploit the high resolution of her evolving technology without breaking the bond of sympathy that her works establish with the beholder/participant.

This bond of sympathy, I would argue, is no small thing. It is very real and virtually ineffable. It derives from the residue of art that remains a thing in our world, the noise of music and the stuff of art, the aspect of a work that cannot be read and thus rendered absent or “other.” This bond resides in those embodied and organized accouterments of art that, in their instantaneity, must invariably exceed our description of it. Gilles Deleuze calls this atmospheric effect “the logic of sense,” the ghost of our patterned, precognitive, sensory perception. In Derrida’s phrase, these effects “haunt” the world we know. By refusing to distance her work from us, Steinkamp relentlessly foregrounds a quick kinesthetic logic that is rarely mentioned these days. It is generally presumed not to exist, it would seem, because any engagement with the extant veil of sense smacks of connoisseurship, of the aesthetic as opposed to the anesthetic. Having said all of this, however, we are still unwilling to deny ourselves our pleasures. We will have our cake regardless of the subversive constituents of the recipe and take it as a special case.

Unfortunately, in our quest for pleasure, we have acknowledged so many special cases in recent years that our categories no longer describe anything, and categories should. Let us ask: Is Frank Gehry’s Bilbao a modernist or a postmodernist structure? Is Richard Serra a minimalist or a materialist or a formalist? Does Jennifer Steinkamp make “video art” or “digital art” or “new media” or “new time-based digital video art” or what? The answer to all these questions, of course, is “Who cares? We like it.” The categorical bond between Steinkamp, Gehry, Serra, Riley, and their younger comrades is nothing more than a presently unfashionable assumption about the “sisterhood of the arts,” that unity of the physical arts, and the transposability of the senses they all exploit. All of these artists operate on the principle that painting, sculpture, music, dance, and architecture share a field of concerns that transcends genre—that they present a repertoire of analogous patterns, effects, and frequencies. Sadly, in a world where the visual arts are presumably bound most intimately to literature, philosophy, and sociology, where they are presumably concerned most urgently with concept, narrative, and representation, this distinction is virtually inexpressible and, consequently, we are touched we know not how.

In order to talk about Jennifer Steinkamp’s work, then, we need to question the extent to which bad language and slovenly categories have diminished our pleasure in good art and occluded the meaning of its success. Because even those who acknowledge the virtue of Steinkamp’s work are hesitant to suggest what it means for art to be good in this particular way. So let us presume for a moment that we should categorize Steinkamp’s project, as it often is categorized, as time-based digital art? How, then, do we distinguish Steinkamp’s work from the work of slacker chicks in Williamsburg who “video” their bodies or from the work of techno-nerds in Nebraska who create “digital collages” that portray Hillary Clinton making love to the aliens from Men in Black? More critically, how do we characterize the time it takes to experience one of Steinkamp’s works? Is that time analogous to the time it takes to walk around a Donald Judd or to the time it takes to watch Hillary Clinton making love to an alien? Obviously, I suspect the former, and suspect further that the motion in Steinkamp’s work is more closely analogous to the shifting play of shadow and reflection we experience walking around a Judd than to the narrative calisthenics of motion pictures.

So a distinction needs to be drawn about kinds of time and motion. In his fine book, The Sense of an Ending, Frank Kermode defines the expectation of imminent closure (a “sense of an ending”) as the primary attribute of literary time—the marker that distinguishes narrative and history from chronology and cumulative lived experience. On the one hand, Kermode locates kairos (time moving toward some conclusion); on the other, he posits chronos (time that simply moves, occasionally in rhythms and cycles, but never toward the determinate point of closure). This distinction, I would suggest, divides the field of “time-based art” succinctly between art grounded in memory, narrative, and representation (kairos) and art grounded in ongoing experience and living consciousness (chronos). The temporal world of Steinkamp’s work, of course, is clearly more chronos than kairos, more closely akin to the peripatetic temporality occasioned by the work of Robert Irwin, Sol Lewitt, and Donald Judd than to narrative film or video. Like Irwin, Lewitt, and Judd, Steinkamp’s work demands time, but it doesn’t demand any strict portion of time, or any particular order of events, or any precedent memory. It is always happening. The moment we arrive is the first moment. The moment we leave is the last moment; there is no beginning or ending.

The distinction between kairos and chronos in the realm of motion is kinesthetically observable. Narrative motion (kairos) moves and steals our mobility; it supplants our own activity with motion in the narrative space of the representation. Pure temporal motion, however, in its intimacy, moves and moves us with it. This has always been what Jennifer Steinkamp’s work is designed to do, regardless of its technological medium. It moves us, quite literally. It demands motion from us in the way that all multidimensional art does, and through the medium of its own movement it exacerbates our sense of ourselves as physical beings in motion. It takes us nowhere, but it breathes in sympathy with us and embodies cycles of visual events that externalize and mimic our condition of being. (The verb “to be,” it should be remembered, derives from the ancient Sanskrit and bears the meaning “to breathe.”) The motion in Steinkamp’s work, then, causes motion and maybe e-motion. Within the domain of her pieces, children go manic and scamper, adolescents vogue, and adults stroll casually around, generally unaware of the fact that they are being moved, that they are dancing with the art. They imbibe their dose of harmony and anxiety, never knowing whence it came.

The ability to move us, physically or emotionally, is an attribute of the best art, of course, but is not exclusive to it. Nor is the ability of representation to stop us dead. Once a week I lecture to a class of students at a university. I move as I lecture and the students move as well, with me or against me. They are never still unless they are asleep or playing a video game on their mobile phone. Occasionally, however, I bring a movie or a filmed interview into class and play it for them. The minute the image flashes on the screen, the class freezes. Henceforth, for the duration of the event, they only move to readjust their postures, because it’s hard to sit frozen. As a group, though, whatever life they had when they were free, when we were just a bunch of bodies in a room, is stolen from them by the image, as it has been stolen from beholders of art for the past twenty years. Steinkamp’s work is not only an antidote to this condition; it is a cure for this perpetual state of suspended animation we inhabit in the ubiquitous presence of images. If she has done nothing else (and she has, in fact, done a great deal more), Steinkamp has let us breathe again and feel the motion of things, and, in our own clumsy way, dance to the music of time.