Hung Liu

The Polity of Immigrants

It used to be that styles and objects traveled, while artists stayed at home; or if they traveled, they soon came home again, bringing exotic manners with them to dazzle the locals. These artists, having traveled and returned, were still assumed to be creatures of the volk or of the finer classes, bound by the conduct and conventions of their own cultural location and social station. Thus, even though they might import, appropriate, and employ the manners and materials of other cultures (the way sorority girls trade party clothes), it was presumed that they could only adapt these alien modalities to the habitus of their “home” culture, as Picasso supposedly adapted the manner of West African sculpture to the conventions of modernist Europe. In this way, the presumed stability of the artist, within his or her culture, was used to validate the power and validity of “culture” itself as an informing concept.

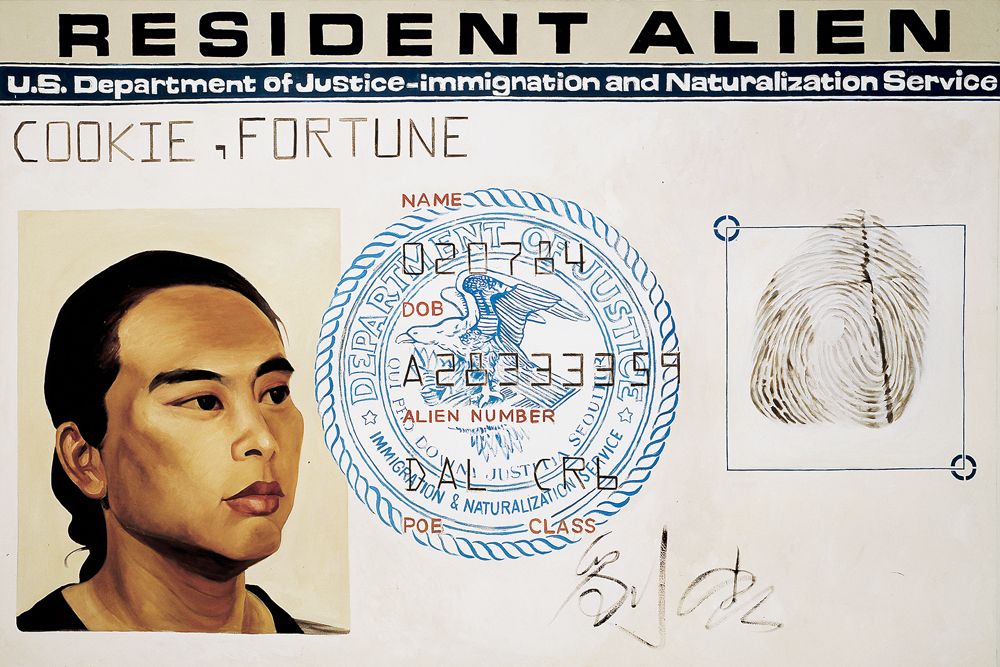

The moment artists begin traveling and not coming home, however—the moment they begin moving from “culture” to “culture,” as Hung Liu and many of her contemporaries have done, the classical idea of “culture,” as proposed in nineteenth-century Germany, begins to dissolve, since, in all of its visible attributes, artists make culture, while culture may no longer be said to make artists. Thus, to anyone who looks, it should be obvious that Hung Liu (an American artist of Chinese descent—who makes “Western” paintings of “Chinese” photographs—who was educated in China in a European tradition—who has struggled to reacquire her Chinese cultural inheritance while living and working in the western United States) may indeed be engaged in “cultural production,” but the works she makes are not “the products of a culture.” They are the products of Hung Liu, and only available to us because the methods, manners, and materials that artists have passed from culture to culture for hundreds of generations have achieved enough transcultural transparency to validate her local resolutions of their multivalent possibilities.

I would argue, then, that Hung Liu’s paintings do not derive their authority from “culture,” but from the transcultural appeal of paintings and the manners of painting she employs. The interest and attraction of Hung Liu’s paintings and the pleasure that we take in them today—in the wrecking yard of history and on the precipice of the millennium—discredits one of the most pervasive fantasies in late twentieth-century art: that “painting is dead.” The truth would seem to be that painting is not “dead” simply because paintings indubitably are (dead, that is)—because paintings are inanimate, inarticulate, portable things of considerable longevity, whose semiotics are invariably iconic and bound by their context. So, even though we can and do “read” paintings, we read them rather as we do the weather and rarely read them in the same way for very long. This is to say that paintings are utterances, like birdsong, but they are not language, and they are not texts, since the defining characteristic of linguistic texts is that, even though their meanings may change depending on their context, the way we read them, does not.

In a text, we can easily distinguish “noise” from “information.” In a painting, one day’s “noise” is the next day’s “information.” The “signifying attribute” is never stable, so the first question with a painting is never what it means, but which of its attributes are meaningful, how they become meaningful, and in what order. In a painting, the brushstroke may function as the primary signifier for one set of beholders, the image might serve this purpose for the next, the scale for the next, the color for the next. This is, and always has been, a matter of local fashion, and, as a consequence, paintings are physically incapable of retaining the emotional, ethical, and institutional meanings that we attribute to them. Such meanings may be assigned to paintings, and we may find them there from time to time, but they do not inhere in them.

Thomas Crow may remark that painting in New York, in the 1980s, was “a shorthand code for an entire edifice of institutional domination exerted through the collectors’ marketplace and the modern museum,” and he may be right (although I do not think he is). This, however, does not mean that Crow’s “shorthand code” will still be intelligible in the 1990s, during which period the same painting may just as easily come to function as a “shorthand code” for the haptic, tactile, fractal modes of information that have become endangered attributes in the digitization of postindustrial culture. Because, in paintings, as opposed to texts, the signifier is not absent. It is a matter of choice and deliberation; it is contingent and protean.

The attraction of painting as a practice, then, has never been its precision of expression, but the fact that it has meant so much for so long, in so many ways and so many places. As Chuck Close puts it, “You tie some animal hairs to a stick, dip it in colored mud and rub that mud on a surface.” Human beings around the world have been doing this for a very long time, and there is every reason for them to keep doing it, simply because the act of painting, due to its ubiquity, calls up a world of meaning out of which one can carve one’s own—in which the beholder may find their own, as well. So it well may be that painting, far from being dead, is only now coming into its own as a vehicle of idiosyncratic expression in the practice of artists like Hung Liu.

Consider it this way: For thousands of years, in Western and Eastern cultures, painting was practiced within the domain of the church, the state, and the academy and subject to their authority. For the last hundred and fifty years in the West, paintings made outside these institutions have concerned themselves with the mechanics of practice and the logic of their history. Since painting today is no longer so concerned or so regulated, it may well be that we are only now beginning to see the practice employed to achieve local solutions that may be said to have cosmopolitan consequences because we are no longer parsing the cultural norms purportedly embodied in artists’ practices. We are, however, appreciating the ways in which various artists exploit the transcultural norms of various practices to their own ends.

Now consider how Hung Liu’s situation as an artist exemplifies this change: She is an American artist of Chinese descent who was educated in China in a European tradition, that of mid-twentieth-century “socialist realism”—a style of heroic painting practiced in China and the Soviet Union and grounded in French academic practice from Poussin to David—with Chinese socialist realism tending more toward the “classical” Poussiniste manner and Russian socialist realism tending toward the gaudy heroism of David’s late “Napoleonic” style. To further complicate this situation, both socialist realism and French academic painting have traditionally opposed themselves in different ways to “mandarin” painterly styles that have both Eastern and Western manifestations.

As a consequence, Hung Liu’s efforts in the United States to familiarize herself with her own Chinese cultural heritage—with the history of Chinese painting and the manner of improvisational, painterly masters like Wang P’o-mo—simultaneously introduced her to the painterly tradition in Western culture that stretches from Titian to de Kooning with its own shifting atmospheres of signification. Not surprisingly, this introduction to Western painterly practice would prove as valuable to Hung Liu’s cultural reorientation as her rediscovery of Chinese gestural painting, since it not only provided a cultural bridge, it provided her with a counterweight to the first artistic academy she would confront in the United States—another Poussiniste establishment at the University of California, San Diego. This American “postminimalist” academy, whose provenance flows from Poussin through David, Puvis de Chavannes, Cézanne, and Duchamp, privileged “conceptual” art rather than the “ideological” art espoused by the Russian and Chinese academies. Over the years, however, this distinction would become as faint as it actually is.

In fact, in the 1970s, the paintings made by the “photo-realist” wing of this academy differed only in minor details and purported intention from the socialist realism in which Hung Liu was trained. Upon arriving in this country, she would exploit the similarity of these painting styles to theatricalize her own peculiar vantage point. To do so, she would exploit the differing status of photographic subject matter in China and the United States. The peculiar power of photo-realism in the United States, of course, was grounded in the fact that photographs are both indigenous and ubiquitous in America. Thus, photo-realist painters sought to redeem this quotidian banality by translating photos into art. Hung Liu’s photo-socialist-realism, however, was informed by the fact that photographs in China were both rare and exotic, yet provided her only visual access to her homeland.

Responding to these local realities, Hung Liu adapted the formalizing strategies of American photo-realism to the more urgent task of humanizing the formality of the Chinese photographs, opening a door to her own past and culture. Thus, in her first body of American work, Hung Liu paints photographs of contemporary China and uses the photograph to distance her manner from the Marxist ideology that informed it in China. At the same time, she works to “open up” the sealed surface of the photograph that in the twentieth century has transformed our historical memory into a strobed sequence of stop-action “moments.” She tries to reestablish that “middle distance” in which the domain of the image and the domain of the artist/beholder intersect—to reestablish that connection and replace the remote instantaneity of photography with the loose, interactive temporality of the “studio time” whose memory is embodied in the finished painting.

In Hung Liu’s paintings, then, the issue is less about making than matching, of establishing some local intersection, some sympathetic resonance between the actions of the artist, the manner of the painting, and the nature of the subject matter. Thus, her paintings of Chinese imperial life are rendered in a Western “mandarin” style of drips and painterly gestures, establishing that bond, and allowing the rhetoric of mourning and mutability that are associated with those “Western drips” to speak of the lost reality of the imperial court. Likewise, when Hung Liu deals with the quotidian subject matter of snapshots, her work segues into a more demotic painterly style that, for Western beholders, evokes both the nineteenth-century “ink wash” and the antiheroic mode of “painterly pop” in the American 1950s—most closely associated with the work of Larry Rivers, early Warhol, Rosenquist, and Wesselmann.

Hung Liu finds what fits, in other words, and this procedure of finding what fits, of achieving local accommodations within the global array of artistic practices, emphasizes an aspect of representation that is rigorously suppressed as long as we regard the artist as coextensive with the culture within which he or she supposedly operates. The fact is that representation is always multivalent: it represents both the objects portrayed and the artist who brings the work into being. Subsequent to that, the work represents the beholders who choose to invest it with public value. If, after a suitable period of time, a representation can be said to represent a substantial segment of those who behold it, it may perhaps be said to represent “the culture,” as Vermeer and Rembrandt are said to represent theirs.

This, however, presumes that the idea of “culture” will remain a viable one in the fluid global tumult that human beings have created for themselves in this century, and the idea of “culture” may not survive. It may be that Hung Liu’s transcultural, local solutions, to her particular desires in her particular social and geographical situation, constitute a new artistic model which is, in fact, as old as America’s transcultural polity of immigrants. This is a model of artistic practice in which works of art represent that which they portray and beyond that represent not the culture but the loose, diverse society of individuals who hold these works in esteem and invest them with social value. In Hung Liu’s case, I count myself a member of this cosmopolitan society.