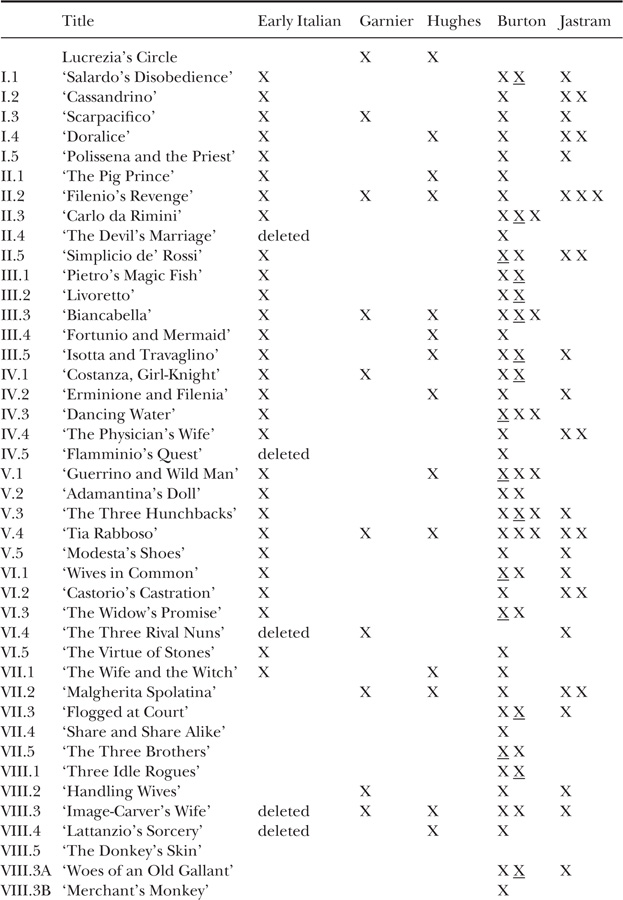

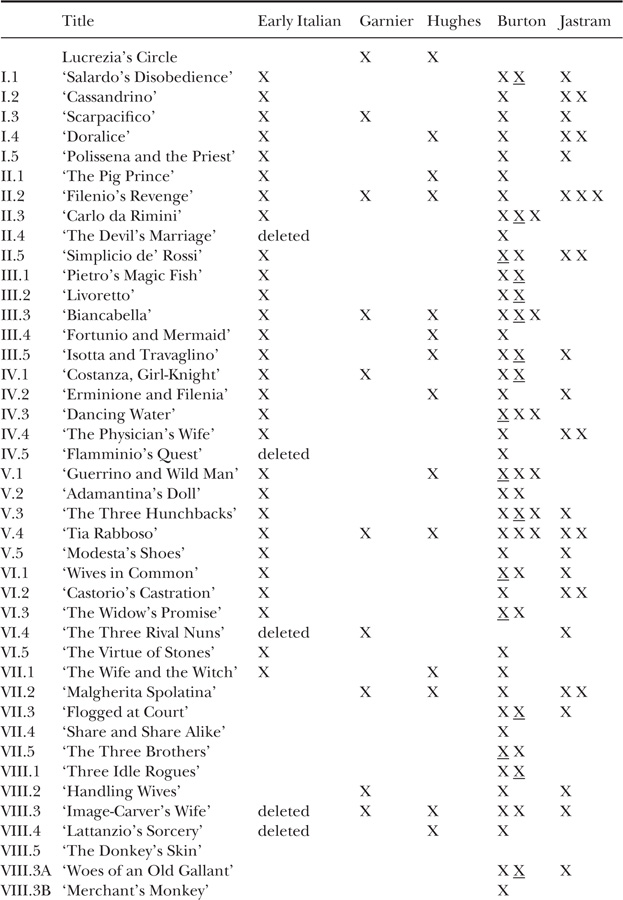

The following chart is an attempt to profile the entire collection in terms of the genres and provenances of the seventy-five stories. It can have but approximate working validity because most of the designations are purely impressionistic or inferential. The ‘types’ of folk tales are usually determined by their characteristic actions or motifs, while ‘genre,’ here, can mean nothing more than ‘kind’ or ‘class,’ such as jest, trickster tale, social vignette, tale of adultery, beast fable, legend, wonder tale – a quadruped’s breakfast of labels. The purpose of the exercise is merely to demonstrate at a glance the variety of the contents, of which we might well ask not ‘what is present?’ but ‘what is missing?’ Straparola’s stories, in rather balanced proportions, make their way through the popular ‘genres’ of the age, from the jest of parking a pasty on a lady’s posterior as an error in the night (XIII.8) to the hauntingly moving tragedy of Malgherita Spolatina, led out to sea, swimming, by her own brothers in a boat, there to drown of exhaustion (VII.2). Such a chart allows for a quick appraisal of the collection’s design, or lack thereof, as a miscellany of popular and erudite tales, the latter recycled through the oral tradition. As for the thorny matter of provenance, there are only educated guesses. This column is the sum of the appraisals made in the course of compiling the commentaries, reflecting my best inferential reasoning about how the stories came to Straparola. The underlying hypothesis is that where cognate versions exist in later oral traditions, often in abundance, of stories lacking any proximate literary versions predating Straparola, probability favours a popular source for the version in the Notti. This is not to say that traces of that story tradition are non-existent in the prior literary record; in fact, most of the stories have left such traces of their passage. But the reason they cannot have served Straparola as sources is that, in order to arrive at what he wrote, he would have been compelled to restore those texts, in every instance, to a version often nearly identical to those surviving centuries later in the oral tradition. The chance that he reinvented the folk versions in such a manner, to my way of thinking, is smaller than infinitesimal. The harder call to make is whether the oral tale was once based on a written source and subsequently assumed the traits of orality. That could well have been the case with certain of the fabliaux-like or novella-like stories, followed by two centuries or more of oral modulation and structural stratification. The parentheses around ‘from written’ mean ‘possibly’ or ‘conceivably,’ nothing more. Speculation remains free. The telling statistic in it all is that of the fifty-three stories in the collection not traceable to Morlini, only five have acknowledged and demonstrable literary sources.

Short Title |

Class of Tale |

Presumed Source |

||

I.l |

‘Salardo’s Disobedience’ |

moralizing novella |

oral (from written) |

|

I.2 |

‘Cassandrino’ |

popular tale of trickery |

folk tale |

|

I.3 |

‘Scarpacifico’ |

popular tale of trickery |

folk tale |

|

I.4 |

‘Doralice’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

I.5 |

‘Polissena and the Priest’ |

novella of adultery |

oral |

|

II.1 |

‘The Pig Prince’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

II.2 |

‘Filenio’s Revenge’ |

novella |

Ser Giovanni |

|

II.3 |

‘Carlo da Rimini’ |

saint’s life / novella |

oral (from written) |

|

II.4 |

‘The Devil’s Marriage’ |

fantasy novella |

folk tale (from written) |

|

II.5 |

‘Simplicio de’ Rossi’ |

novella |

oral (from written) |

|

III.1 |

‘Pietro’s Magic Fish’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

III.2 |

‘Livoretto’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

III.3 |

‘Biancabella’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

III.4 |

‘Fortunio and Mermaid’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

III.5 |

‘Isotta and Travaglino’ |

novella of adultery |

oral / popular |

|

IV.1 |

‘Costanza, Girl-Knight’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

IV.2 |

‘Erminione and Filenia’ |

novella |

Francesco Bello |

|

IV.3 |

‘Dancing Water’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

IV.4 |

‘The Physician’s Wife’ |

novella |

Ser Giovanni |

|

IV.5 |

‘Flamminio’s Quest’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

V.1 |

‘Guerrino and Wild Man’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

V.2 |

‘Adamantina’s Doll’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

V.3 |

‘The Three Hunchbacks’ |

novella-farce |

folk tale (fabliau) |

|

V.4 |

Tia Rabboso’ |

novella of adultery |

oral / popular |

|

V.5 |

‘Modesta’s Shoes’ |

novella / popular tale |

new / oral |

|

VI.l |

‘Wives in Common’ |

novella |

Boccaccio, et al. |

|

VI.2 |

‘Castorio’s Castration’ |

pop. tale / jest |

oral / popular |

|

VI.3 |

‘The Widow’s Promise’ |

novella / anecdote |

oral / popular |

|

VI.4 |

‘The Three Rival Nuns’ |

jest / popular tale |

oral / popular |

|

VI.5 |

‘The Virtue of Stones’ |

anecdote / jest |

Morlini |

|

VII.l |

‘The Wife and the Witch’ |

fantasy novella of adultery |

oral / popular |

|

VII.2 |

‘Malgherita Spolatina’ |

novella |

oral / popular |

|

VII.3 |

‘Flogged at Court’ |

jest |

oral / popular |

|

VII.4 |

‘Share and Share Alike’ |

novella / anecdote |

oral / popular |

|

VII.5 |

‘The Three Brothers’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

VIII.l |

‘Three Idle Rogues’ |

jest / popular tale |

folk tale |

|

VIII.2 |

‘Handling Wives’ |

novella |

oral / popular |

|

VIII.3 |

‘Image-Carver’s Wife’ |

novella from fabliau |

oral (from written) |

|

VIII.4 |

‘Lattanzio’s Sorcery’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

VIII.5 |

‘The Donkey’s Skin’ |

jest |

Morlini |

|

VIII.3A |

‘Woes of an Old Gallant’ |

novella |

oral (from written) |

|

VIII.3B |

‘Merchant’s Monkey’ |

jest |

Morlini |

|

IX.1 |

‘King Galafro’ |

novella |

oral (from written) |

|

IX.2 |

‘Rodolino and Violante’ |

novella |

Boccaccio |

|

‘Francesco Sforza’ |

pseudo-hist. novella |

written / oral |

||

IX.4 |

‘Papiro Schizza’ |

jest |

oral / popular |

|

IX.5 |

‘Bergamasques’ |

jest |

oral / popular |

|

X.1 |

‘Veronica’s Jewels’ |

jest / anecdote |

no known sources |

|

X.2 |

‘The Lion and the Ass’ |

beast fable |

popular (from written) |

|

X.3 |

‘Cesarino and Dragon’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

X.4 |

‘Andrigetto’s Testament’ |

jest / anecdote |

oral / popular |

|

X.5 |

‘Rosolino’s Confession’ |

novella / anecdote |

oral (from written) |

|

XI.l |

‘Constantino’s Cat’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

XI.2 |

‘The Grateful Dead’ |

wonder tale |

folk tale |

|

XI.3 |

‘Dom Pomporio’ |

jest based on proverb |

oral / popular |

|

XI.4 |

‘The Stolen Veal’ |

jest |

Morlin |

|

XI.5 |

‘Frate Bigoccio’ |

novella / anecdote |

Morlin |

|

XII.l |

‘Florio’s Jealousy’ |

novella / anecdote |

Morlin |

|

XII.2 |

‘The Fool’s Blackmail’ |

novella/jest |

Morlin |

|

XII.3 |

‘Pozzuolo’s Wife’ |

novella / cautionary tale |

Morlin |

|

XII.4 |

‘The Disobedient Sons’ |

novella / anecdote |

Morlin |

|

XII.5 |

‘Pope Sixtus IV |

pseudo-hist. tale |

Morlin |

|

XIII.l |

‘Madman and Hunter’ |

jest / tale |

Morlin |

|

XIII.2 |

‘Diego and the Friar’ |

jest |

Morlin |

|

XIII.3 |

‘Spaniards and Germans’ |

jest |

Morlin |

|

XIII.4 |

‘The Servant and the Fly’ |

jest / popular tale |

Morlin |

|

XIII.5 |

‘The Fateful Sack’ |

Apuleian farce |

Morlin |

|

XIII.6 |

‘The Good Day’ |

jest / popular tale |

Morlin |

|

XIII.7 |

‘Giorgio and His Master’ |

jest / popular tale |

Morlin |

|

XIII.8 |

‘Midnight Famine’ |

jest |

Morlin |

|

XIII.9 |

‘Hermaphrodite Nun’ |

novella / anecdote |

Morlin |

|

XIII.10 |

‘Doctor of Laws’ |

popular tale / anecdote |

Morlini |

|

XIII.11 |

‘The Novice in the Barn’ |

novella |

written sources including Morlini |

|

XIII.12 |

‘Healing of Guglielmo’ |

anecdote |

no known sources |

|

XIII.13 |

‘Pietro Rizzato’ |

moral tale |

Morlini |

Morlini |

22 |

Wonder tales (& beast fable) |

17 |

Oral with possible written affiliations |

11 |

Other popular tales, farces, anecdotes from oral sources |

17 |

No known sources, written or oral |

2 |

From known literary sources other than Morlini |

5 |

From written source, but source unknown |

1 |

Scattered at random throughout the commentaries to follow are story-type numbers originating in the universally employed Aarne-Thompson Types of the Folktale. That work, now called Types of International Folktales, as revised by Hans-Jörg Uther, is the source of the corresponding numbers supplied below. Also appearing sporadically throughout the commentaries are motif numbers derived from Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk-Literature – numbers which are comprehensively listed by D.P. Rotunda in his Motif-Index of the Italian Novella in Prose, and again by Donato Pirovano in his edition of Le piacevoli notti at the bottom of the first page of each story. Given this redundant record of the motif numbers, there is far less need to supply them again here. In the course of the commentaries to follow, my intention has been to identify and profile the many works antecedent to the Piacevoli notti that contribute to an understanding of his story types, and in the process of doing so I have devised analyses tantamount in some cases to early histories of the relevant types. In the centuries after Straparola, those type traditions often luxuriated into proportions far beyond my purposes, resulting in a selective representation of their afterlives. For those wishing to corroborate my type histories and fill in the later centuries from folklore reference works incorporating the ATU numbers, the following, modified from the list initially compiled by Luisa Rubini for the Enzyklopädie des Märchens, should prove useful.123

Night |

Story |

ATU Number |

Description of the Type |

I. |

1 |

910A |

Excellent advice |

I. |

2 |

1737 |

Priest in the sack |

I. |

2 |

1525A |

The master thief |

I. |

3 |

1538 |

Revenge of the betrayed, or Deceiving the deceivers |

I. |

3 |

1551 |

The cheating contest |

I. |

3 |

1539 |

Trickery and gullibility |

I. |

3 |

1535 |

Unibos or One-ox |

I. |

4 |

510B |

The princess in the chest |

II. |

1 |

433B |

König Lindwurm (a wingless dragon) |

1 |

441 |

Hedgehog Hans |

|

II. |

1 |

425A |

The beast bridegroom |

II. |

4 |

1164B |

Belfagor |

II. |

4 |

1862B |

The sham physician and the devil in league |

III. |

1 |

675 |

The lazy boy |

III. |

2 |

531 |

Ferdinand the Faithful and Ferdinand the Unfaithful |

III. |

2 |

554 |

The grateful animals |

III. |

2 |

314 |

The girl with the golden hair |

III. |

3 |

403 |

The black bride |

III. |

3 |

706 |

The girl without hands |

III. |

4 |

316 |

The nixie in the pond |

III. |

4 |

554/159 |

The quarrel over the stag |

III. |

4 |

665 |

Grateful animals grant powers of metamorphosis to hero |

III. |

5 |

889 |

The faithful servant |

IV. |

1 |

884/514 |

Woman dressed as a man |

IV. |

1 |

328 |

Corvetto |

IV. |

2 |

1418 |

Isolde’s trial by ordeal |

IV. |

3 |

707 |

The three golden sons |

IV. |

4 |

1364 |

Wife of the sworn brothers |

IV. |

5 |

326 |

The boy who learned to fear |

V. |

1 |

502 |

The wild man |

V. |

2 |

571C |

The biting doll |

V. |

3 |

1536B |

The three hunchbacks |

V. |

4 |

1419C |

The one-eyed husband |

VI. |

1 |

1424 |

The nose-maker |

VI. |

2 |

1133 |

How to get fat |

VI. |

3 |

1565 |

Agreement not to scratch |

VII. |

1 |

891 |

The man who abandoned his wife |

VII. |

2 |

666 |

Hero and Leander |

VII. |

3 |

1610 |

The sharing of gifts and blows |

VII. |

5 |

653 |

The four skilful brothers |

VIII. |

1 |

1950 |

The laziness contest |

VIII. |

2 |

901 |

The taming of the shrew |

VIII. |

3 |

1359C |

Tricks of adultery |

VIII. |

4 |

325 |

The magician’s apprentice |

VIII. |

5 |

1862C |

The naïve diagnosis |

IX. |

3 |

958 |

The shepherd’s cry for help |

IX. |

4 |

1562A |

The barn is burning |

IX. |

4 |

1940 |

Extraordinary names |

X. |

2 |

103C |

The old donkey meets the bear |

X. |

2 |

118 |

The horse that terrifies the lion |

X. |

2 |

125B |

Contest between the donkey and the lion |

X. |

3 |

300 |

Dragon, battle, and dragon-slayer |

XI. |

1 |

545B |

The cat in boots |

XI. |

2 |

505 |

The grateful dead |

2 |

1355A |

Lord of all |

|

XII. |

3 |

670 |

The man who knew the language of animals |

XIII. |

2 |

1526A |

One who leaves without paying the bill |

XIII. |

4 |

1586 |

The fly on the judge’s nose |

XIII. |

4 |

1600 |

The buried sheep’s head |

XIII. |

5 |

958C |

Robber shroud |

XIII. |

6 |

1641 |

Doctor Know-all |

XIII. |

7 |

1562B |

The list of duties |

XIII. |

8 |

1775 |

The hungry priest |

The names of narrators in parentheses are those of the young ladies originally designated to tell the story by the drawing of lots, but who were then replaced. The forward slash between setting locations indicates movement in the story from one place to the other.

|

Burton’s Titles |

Narrator |

Setting |

I.1 |

The Disobedience of Salardo |

Lauretta |

Genoa / Monferrato |

I.2 |

The Stratagems of Cassandrino |

Alteria |

Perugia |

I.3 |

Outwitting the Robbers |

Cateruzza |

Near Imola |

I.4 |

Incestuous Designs of a King |

Eritrea |

Salerno / England |

I.5 |

Surprised with a Priest |

Arianna |

Venice |

II.1 |

From Swine to Man |

Isabella |

Anglia (England) |

II.2 |

The Scholar and the Three Ladies |

A. Molino |

Bologna |

|

|

(Fiordiana) |

|

II.3 |

Punishment of a Libertine |

Lionora |

Rimini |

II.4 |

The Devil Worsted by his Wife |

Benedetto |

? / Amalfi |

|

|

(Lodovica) |

|

II.5 |

The Lover in the Sack |

Vicenza |

Santa Eufemia, Padua |

III.1 |

Story of Pietro the Fool |

Cateruzza |

Capraia Island, Liguria |

III.2 |

Livoretto’s Wonderful Horse |

Arianna |

Tunis / Cairo / |

|

|

|

Damascus |

III.3 |

The Damsel and the Snake |

Lauretta |

Monferrato / Naples |

III.4 |

Fortunio and the King’s Daughter |

Alteria |

Lombardy / Polonia |

III.5 |

The Outcome of a Woman’s Wiles |

Eritrea |

Bergamo |

IV. 1 |

The Girl Knight |

Fiordiana |

Thebes / Bithynia |

IV. 2 |

The Husband Outwitted |

Vicenza |

Athens |

IV.3 |

Misadventures of Royal Offspring |

Lodovica |

Provino (Provence) |

The Physician’s Wife |

Isabella |

Padua |

|

IV.5 |

The Finding of Life |

Lionora |

Ostia / environs |

V.1 |

The Wild Man of the Woods |

Eritrea |

Sicily / Manda |

V.2 |

The Wonder-working Doll |

Alteria |

Bohemia |

V.3 |

The Three Hunchbacks |

A. Molino |

Valsabbia / Venice / |

|

|

(Lauretta) |

Rome |

V.4 |

An Adulterous Wife’s Ruse |

Benedetto |

Salmazza, Padua |

|

|

(Arianna) |

|

V.5 |

Shoes for Love-service |

Lucrezia |

Pistoia |

|

|

(Cateruzza) |

|

VI.1 |

Friends with Wives in Common |

Alteria |

Genoa |

VI.2 |

Castrated and Content |

Arianna |

Carignano, near Fano |

VI.3 |

The Widow’s Broken Compact |

Cateruzza |

Venice |

VI.4 |

Three Rival Abbesses |

A. Bembo |

Florence |

|

|

(Lauretta) |

|

VI.5 |

The Virtue of Stones |

Eritrea |

Bergamo |

VII.1 |

Wife, Harlot and Witch |

Vicenza |

Florence / Flanders |

VII.2 |

Daring Death for Love |

Fiordiana |

Ragusa, Dalmatia |

VII.3 |

Flogged at the Pope’s Court |

Lodovica |

Brescia / Rome |

VII.4 |

Share and Share Alike |

Lionora |

Naples |

VII.5 |

The Three Brothers |

Isabella |

‘Our city’ / Chios |

VIII.1 |

The Three Idle Rogues |

Eritrea |

Siena / Rome |

VIII.2 |

The Right Handling of Wives |

Cateruzza |

Corneto, near Rome |

VIII.3 |

The Sin of Luxury |

Arianna |

Florence |

VIII.4 |

The Secret Arts of Sorcery |

Alteria |

Messina |

|

|

(Lodovica, 1555) |

|

VIII.5 |

The Donkey’s Skin |

Lauretta |

Antenorea (Padua) |

|

|

(Veronica, 1555) |

|

VIII.3A |

The Woes of an Old Gallant |

Arianna |

‘Our city’ |

VIII.3B |

The Merchant’s Monkey |

Alteria |

Genoa / Flanders |

IX.1 |

Vain Precautions |

Diana |

Madrid |

IX.2 |

The Fatal Grief of Love |

Lionora |

Budapest / Austria |

IX.3 |

Whilst Chasing a Stag |

Isabella |

Milan / environs |

IX.4 |

The Danger of a Little Learning |

Vicenza |

Brescia |

IX.5 |

Outwitting the Wise |

F. Beltramo |

Bergamo |

|

|

(Fiordiana) |

|

X.1 |

Naked as When Born |

Lauretta |

Verona |

X.2 |

Ser Brancaleone |

Arianna |

Morea, Arcadia |

X.3 |

With the Help of Beasts |

Alteria |

Calabria / Sicily |

X.4 |

The Strange Testament |

Eritrea |

Como |

X.5 |

For Love of a Son |

Cateruzza |

Pavia |

XI.1 |

The Fairy as a Cat |

Fiordiana |

Bohemia |

XI.2 |

The Reward of Goodness |

Leonora |

Trino, near |

|

|

|

Monferrato / Novara |

XI.3 |

Pot Calling the Kettle Black |

Diana (Lodovica) |

‘Famous monastery’ |

The Repast of Veal |

Isabella |

Vicenza |

|

XI.5 |

The Gloves |

Vicenza |

Rome / Florence |

XII.1 |

The Garb of Religion |

Lionora |

Ravenna |

XII.2 |

The Reward of Loquacity |

Lodovica |

Pisa |

XII.3 |

Conjugal Correction |

Fiordiana |

Naples / Pozzuolo |

XII.4 |

Good Counsel |

Vicenza |

Pesaro |

XII.5 |

The Two Vases |

Isabella |

Rome / Naples |

XIII.1 |

The Wise Madman |

Casale of Bol. |

England / forest |

XIII.2 |

The Spaniard’s Feast |

S. Lucrezia |

Cordova |

XIII.3 |

Servant’s Chatter |

Pietro Bembo |

A hostel |

XIII.4 |

Post-mortem Cuckoldry |

S. Veronica |

Ferrara |

XIII.5 |

The Fatal Sack |

Bernardo Capillo |

Pistoia |

XIII.6 |

The Good-day’s Greeting |

S. Chiara |

Cesena, Romagna |

XIII.7 |

The Letter Killeth |

F. Beltramo |

Padua |

XIII.8 |

The Peasant’s Pasty |

Lauretta |

Noventa, Padua |

XIII.9 |

The Hermaphrodite Nun |

A. Molino |

Salerno |

XIII.10 |

The Subtle Ignoramus |

Cateruzza |

Naples |

XIII.11 |

The Novice |

Benedetto of T. |

Near Rovigo (Ferrara) |

XIII.12 |

Doctor Common-sense |

Isabella |

Brittany (Normandy) |

XIII.13 |

The Friends |

Vicenza |

Padua |

Straparola’s stories were first illustrated at the end of the sixteenth century, beginning with the Zanetti edition of 1597, followed by the editions (by the same publisher) of 1601, 1604, and 1608. Without having inspected copies of each, it cannot be said with certainty that the same set of woodcuts was used (four stories were deleted from the 1608 edition), but early practice and the recycling of such valuable printing-house commodities suggest that they were.124 (Those I saw were from the edition of 1608.) The work, by that date, was routinely printed in two octavo volumes – the first of which, in the 1608 edition, contains twenty-eight woodcuts illustrating the first thirty-one stories, less the three deleted by the censors (II.4, IV.5, and VI.4). The illustrator was clearly commissioned to produce one picture for each story. The second volume undoubtedly contains a similar number of woodcuts and arguably more, given that forty-two stories remained, less the seven from this group deleted by the authorities. This represents a substantial endeavour, whatever the final count, and a clear commitment to the book’s ongoing commercial success, despite the indexing and censorship. Some of these woodcuts are more accomplished than others in terms of poses, designs, and execution. A few are striking in the detail of their interiors, or for their accomplished perspectives. By contrast, that of Guerrino standing with his bow and arrow beside the prison grate where the wild man is imprisoned (V.1) is rigid and two-dimensional. The depiction of Tia Rabboso performing her incantations and dancing around her husband, his head inside the sifting basket (V.4), is a successful representation of a scene that would attract all the subsequent illustrators. Surprising to see, meanwhile, are the two which depict conjuring circles surrounded by mysterious symbols (VI.1 and VII.1), given the Church’s displeasure with anything having to do with black magic, spells, divination, and necromancy. The latter is of the witch Gabrina and the naked Isabella standing within the magic circle as the devil Farfarello enters at the left. Three design plans are employed in relation to the narratives: a single scene taking up the entire foreground; two scenes juxtaposed side by side on a split field; or double and even triple story episodes represented in the foreground, near, and distant backgrounds. These strategies relate to matters of aesthetics and late Renaissance design; representations of these pictorial strategies may be seen, for example, in the woodcuts illustrating Sir Thomas North’s The Fables of Bidpai (The Moral Philosophy of Doni), published in 1570 with blocks cut in Antwerp.125 The illustrator must choose either one salient scene to represent the entire story – usually a culminating moment – or show relations of cause and effect, or before and after, through the double use of the space. The picture then achieves a kind of kinetic effect as the viewer fills in the peregrinations that lead from one episode to the other. Insofar as these woodcuts are placed before each text, in a sense they also serve as emblems or enigmas that can only be explained through reading. By dint of these preliminary pictures, the stories become explanatory in the same way that the texts of the emblem books complete the meanings of the images.

Coming to later centuries, Straparola illustrated calls for an introduction to two little-known but accomplished, late nineteenth-century painters and book illustrators: Jules Arsène Garnier (1847–89), who was called upon to supply fourteen images for the 1882, French, four-volume edition of Les facétieuses nuits; and Edward Robert Hughes (1849–1914), who was commissioned for twenty images to grace the Waters translation, which first appeared in the luxurious, two-volume edition of 1894 described above. All of these illustrations were subsequently brought together in the privately printed, four-volume edition of the Waters translation for the Society of Bibliophiles, the first printing in 1898, the second in 1901 (together totalling 1,300 numbered copies). Clearly, both the French and English publishers had recognized the great pictorial potential in these stories and, to redeem their ventures, relied upon the love of handsome and exclusive illustrated books among the purchasers of the Victorian and Belle-Époque periods. For lack of particulars, we can only presume that both illustrators were provided with copies of the stories and invited to choose the subjects, plots, and scenes that most readily inspired their artistic predilections. Intriguingly, they hit upon only a few stories in common, seizing upon moments that appealed to their respective creative impulses or that were deemed the most representative moments of the stories themselves. Those two criteria must, in some ways, have been in competition. There is a particular pleasure in examining their pictures to determine, first, the precise moments in the stories which they represent, perhaps even to supply the corresponding sentences or phrases; second, why the exact scenes they chose best epitomize entire stories; and third, how their artistic talents, tastes, and proclivities found expression through the treatment of their subjects.

The matter of their periodicity merits comment, for both artists were men of their times. Garnier, arguably, makes a more concerted effort than Hughes to create interiors appropriate to historical pasts, or at least to keep them relatively spare and neutral, whereas Hughes luxuriates in the rich textures and decorative clutter of his own age. In matters of period costume, however, Hughes may have the better imagination. Garnier’s clerics appear particularly unconvincing and his young women at times look like gypsies, but specialists in these matters will be more adequately informed. Garnier has a sense of humour, of drama, and of the erotic, as well. The pose of the naked young woman fleeing the barn as the novice falls down from the loft (XIII.11) is hauntingly familiar from a formerly depicted scene of disaster. Hughes, by contrast, is thoroughly imbued with the aesthetics of the Pre-Raphaelites and has a penchant for beautiful women, nudity, and eroticism with overtones of mysticism, along with a tendency towards expressionist symbolism all his own. Many of his illustrations began as full-scale salon paintings and are circulated today under different titles. ‘Bertuccio’s Bride’ (XI.2) is one of his best known in this regard (it is still widely available as an art print). As the beautiful maiden, the subject of male barter, stands apprehensively in the background, Bertuccio spreads all his wealth on the ground before the rigid and death-like man, hooded and armed with a massive sword. The scene is the psychologically revealing moment of contest and suspense that culminates most renditions of ‘The Grateful Dead.’ But without that story line, the figures assume enigmatic poses, their respective gestures generating rich symbolic overtones at correspondingly archetypal levels: ‘Youth, Death, and the Maiden,’ or ‘The Vanity of Worldly Goods.’ His painting called ‘Biancabella and Samaritana’ (III.3) – representing the moment at which the snake sister provides the heroine with a beautifying bath of milk – when viewed independently from the narrative depicts a childish Venus, delightfully pretty, innocently naked, and erotically entwined by a serpent. Out of context, the snake might incite a number of interpretations, and perhaps intentionally so, for in 1895 the painting was taken to Venice for the Biennale where it raised a sensation. The most mystical of them all is the portrait of Isabella Simeoni (from ‘The Wife, the Courtesan, and the Witch,’ VII.1) on the back of the devil Farfarello, here converted into a magnificent black Pegasus flying high above the city of Florence with its Duomo and the River Arno in clear view below. She is seated side-saddle, holding the backs of the wings, her flaxen hair streaming in the wind. Today, the picture is known as ‘The Valkyrie,’ far from its source of inspiration. But Hughes was not always a symbolist. A naked man leaping from on high to escape the fatal cut in the presence of the two kneeling nuns and the image-carver’s bemused wife may be but a naked man … (VIII.3). This grand ‘tutti’ scene is the finale of the tale and features the escapee suspended in midair; it is the work of a consummate illustrator of stories, revealing meanwhile that Hughes had a reasonable sense of humour. At the same time, the symbolism of the world-upside-down in the nuns’ amazement at the miracle of the resurrected Christ appearing in the person of a ‘defrocked’ priest is not Hughes’s symbolism, but originates in the story itself.

Jules Garnier was born in Paris but trained for a time in Toulouse and later at the École des Beaux-Arts, where he was the student of J.-L. Gérôme. He travelled a great deal thereafter, venturing as far as Holland, Spain, and Morocco. The restive and truculent scenes he found in the pages of Rabelais marked his artistry and some of the Straparola illustrations are clearly in this vein. Beginning in 1869, the Salon exhibited his works annually until 1888. In his lifetime he achieved a considerable reputation for his paintings of social drama, many of them concerned with punitive attitudes towards extramarital sexuality and the exploitation of women, as in ‘Constat d’Adultère’ (1883); ‘Supplice des Adultères’ (1876), set in Medici Florence; and ‘Le Droit du Seigneur’ (1872). These themes are not demonstrably visible, however, in the Straparola interpretations. Garnier had been sickly in his youth, followed the tastes of the academy, married twice (his first wife died a year after their marriage), had an influence on Seurat, and was by no means a radical, although he was a man of polemical tendencies in his painting.126 Tellingly, only shortly after Garnier had completed his illustrations for Les facétieuses nuits (1882), he was engaged in the creation of a vast circular panorama of Constantinople. It was a study in geometry and perspective involving architecture and landscape, to be viewed by popular audiences from a platform in the centre of the room.127

E.R. Hughes was born in London, an only child who nevertheless spent much of his time with his uncle – Arthur Hughes, the painter – and Arthur’s five children. He was of a gentle and docile nature, which continued with him throughout his career; he was retiring and without marked ambition, yet he was widely liked and admired. He entered the Royal Academy Schools after being encouraged by his uncle, became a student of the watercolours of Edward Burne-Jones, and was part of an active circle of young painters and architectural draughtsmen. He started exhibiting at the Royal Academy in 1872 and had his own studio in Chelsea by the time he met Burne-Jones in person. The greatest part of Hughes’s early production was devoted to portraiture, but at the fashionable galleries and shows he turned towards symbolist subjects, often painted in rich golds and blues, many of his themes influenced by Italian literature. He took particular pride in his fine gift for representing nudes, including the several to be seen in the Straparola illustrations, their snowy textures in stark contrast to the dark backgrounds. He was also among the outstanding illustrators of Shakespeare’s plays. Later in his career he became an assistant to Holman Hunt who, with his diminishing eyesight, needed a careful and meticulous collaborator; Hughes actually finished some of his most famous paintings, including ‘The Light of the World’ in St. Paul’s Cathedral and ‘The Lady of Shalott.’ Among the paintings still in his own studio at the time of his death was his splendid ‘Night and her Train of Stars,’ which was purchased from Hughes’s estate by friends and presented to the Birmingham Art Gallery in 1914.

The effect of these often pictorially imposing images, positively or adversely, is the transposing of Straparola’s stories to other ages and airs. With Hughes in particular, the Victorian world is before our eyes, as in the love scene between Galeotto and Feliciana (IX.1). We see them in a Pre-Raphaelite pose in a bourgeois parlour with a period piano, a Wilton-style carpet, a Chinese, multi-drawered chest in the background covered with flowers in vases, and still more potted flowers. These scenes likewise interpret characters in most particular ways through their gestures and expressions, their levels of social energy or lassitude. Ultimately, they may be said to violate the imagination in all the ways for which book illustrators have been blamed, which is essentially by imposing upon and replacing our own text-generated representations. Yet these images are, in themselves, no more tyrannical than the interpretations of theatrical roles by individual actors. They lend particularity, substance, and often a grandeur beyond the capacities of scantier imaginations. In brief, they are readings, an added aesthetic dimension – and, in the instances of Hughes and Garnier, often very fine pictures in their own rights, employing all the most refined workshop methods from a great age of book illustration.

The images by the two hands in the Burton edition of 1906 are of a different order. Presumably both artists were commissioned by Charles Carrington, the publisher, to embellish a semi-pirated translation intent upon displacing the Garnier-Hughes-Waters extravaganza of 1898, published for the Bibliophiles. Certainly in numbers of images, this edition takes the prize. Every story is graced, often with two or three pen and ink drawings of considerable skill scattered throughout, the text forming columns around them. They are signed by a Dombrecht or Gombrecht and appear to have been executed in 1900 – six years before the book was released. News of this artist would have been welcomed, but only at a cost proportional to the level of my curiosity. This holds equally true for the Lebègue who is responsible for the spirited but naïve and sometimes cartoon-like full-page aquarelles. These are printed on thick paper and surrounded with elaborate rose-gray or burnt-sienna borders featuring intertwined figures and stylized knights with lambrequins, or naked caryatids and harpies – all too redolent of illustrated fairy-tale books for children. The colours are nevertheless varied and subtle and the nature scenes, with their ferns, flowers, and tuffets, have a significant charm bespeaking the tastes of an age. These aquarelles, no doubt expensive to produce, are covered with printed paper tissues identifying nights, fables, and the specific texts to which the pictures refer.

The pen and ink illustrations by Inge Jastram of the twenty-five Straparolan stories in Die ungetreue Polissena (1989) are of yet a different order, for while they are rather more minimal in their execution they are full of movement, expression, humour, and conceptual imagination. These are not essays in scenic representation or historicism, but in intrapersonal relations, moods, human frivolity, or human vanity, with playful eroticism galore. The contrasting expressions on the faces of the three nuns staring at the priest who is masquerading as the nude Christ on the cross are, to borrow a cliché, precious (VIII.3). These drawings contribute generously to the spirit intended by the publisher in choosing all of Straparola’s raciest tales, a collection to which is appended the descriptive title, ‘ergötzliche and tolldreiste Novellen aus dem alten Italien’ (amusingly absurd, impudent, and wanton tales out of old Italy). Of the nun about to catch an apricot seed, Jastram has her standing on her head, headgear and all, with her robe down around her waist, prepared to seize the falling pit between her nether cheeks (VI.4). No greater graphic fun with Straparola could be imagined. Jastram creates a spirit of Renaissance life of her own, reading the stories in a personal way and taking impressions, which she then drafts into these striking and memorable images.128 This artist has also illustrated Lucian of Samosata’s Hetärengespräche (Dialogues of the courtesans, 1983) and Süsser als Liebe is nichts (Nothing is sweeter than love, 1988), the sayings and poems of nine Greek women from antiquity.

A Chart of Selected Illustrators of the Piacevoli notti