Chapter Six

Satyamurthi—the Link that Snapped

The interaction between popular entertainment and

politics in Tamil Nadu has intrigued observers for long. By a historical process unparalleled elsewhere, all five chief ministers who have ruled Tamil Nadu since 1967 have been associated with the film world. They also have a second commonality: they belonged, in one way or another, to the Dravidian movement. But the association is not just a post-Independence phenomenon, but has a long history, which goes back to the early days of the freedom movement. This association was in fact established by S Satyamurthi, the nationalist leader, who belonged to the Congress party. This crucial beginning and Satyamurthi’s role in it has not been studied so far. Had this association between the leaders of the Indian National Congress and the entertainers of Tamil Nadu continued beyond Satyamurthi’s time, the history of the Dravidian movement, and of Tamil Nadu, could well have been different.

Born in 1887 at Tirumayam, near Pudukottai, in a lawyer’s family, Satyamurthi pursued his higher education in Madras and graduated from the Madras Christian College. After earning a degree in law, he joined the bar in Madras but was soon drawn to active politics. He made his political debut in 1919 at a Congress conference in Kanchipuram where his spirited attack on the ideas of Annie Besant attracted the attention of Sarojini Naidu and other leaders of the Congress, who identified him as a potential publicist for the party. Soon he came to lead the nationalist faction of the Congress, which was then based in Madras.1

His fluency in both English and Tamil, coupled with oratorical abilities, helped him play his assigned role with confidence and aplomb and his speeches during his 1925 tour of England projected the Congress’ point of view clearly and forcefully. Satyamurthi’s role in the nationalist movement grew steadily: from 1923 to 1930, he was a member of the Madras Legislative Council and was also very active in the Civil Disobedience movement in the late 1920s. During this period, he developed close relationships with artistes of the entertainment world, and subsequently brought many of them into political activism.

In 1935, Satyamurthi was elected to the Indian Legislative Assembly in Delhi where he made a considerable impact as a debater and as the deputy leader of the Congress party. When the Congress contested the elections in 1937, he led the party’s election campaign in the Madras presidency and in an astute move, harnessed the talents of stage and screen artistes in support of the campaign. Later as the Mayor of Madras, and right up to his premature death at the age of fifty-six in 1943, he maintained an active association with artists .2

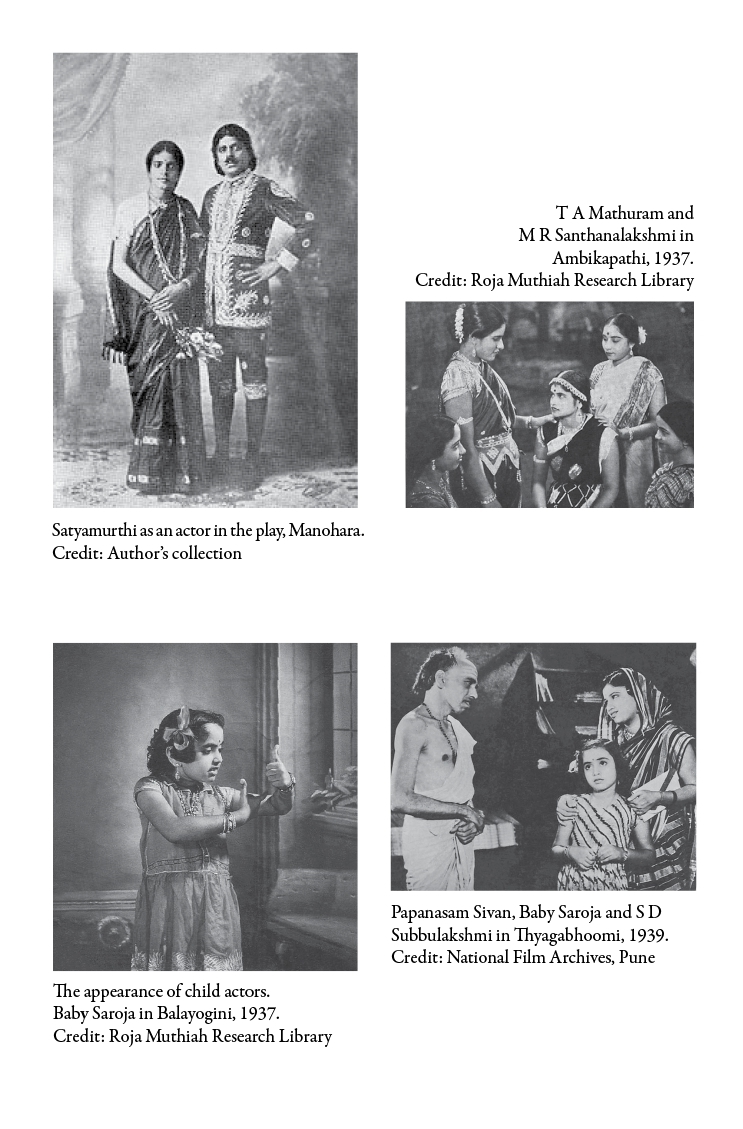

Satyamurthi was first drawn to the world of entertainment when he started his legal practice in Madras. The amateur drama club, Suguna Vilas Sabha of Madras, founded by Judge P Sambanda Mudaliar in 1891 offered a forum for those interested in theatre activities. Suguna Vilas Sabha was an elitist outfit in which bureaucrats, lawyers and other professionals took part, as distinct from commercial drama companies popular with the masses at that time. Satyamurthi joined this troupe and acted in many productions; his performance as the jester in the Sanskrit play Clay Cart / Mrichakatika

and as Manoharan in Manohara,

both within a week of taking over as the president of the Tamil Nadu Provincial Congress Committee, received highly favourable notice.3

After watching a performance of As You Like It

at the Memorial theatre at Stratford-on-Avon in England, he had said, ‘

I visited the place as a pilgrim from Suguna Vilas Sabha.’4

He was soon elected as the vice-president of the Sabha and later held the office of Tamil conductor, a designation assigned to individuals entrusted with the responsibility of directing Tamil dramas.5

As he grew more active in politics, Satyamurthi realized that for building up a popular political base for the Congress, he needed a different set of connections with the people: the world of commercial drama could serve his purpose. In fact, as early as 1922, Motilal Nehru had written to Satyamurthi emphasizing the need to gather support for the nationalist faction in the Congress, ‘Yours is truly a benighted province in this matter... I doubt very much that we shall have any appreciable number to support us unless an intensive propaganda is at once started.’ 6

The performances of commercial drama companies were the most prevalent form of popular entertainment during this period. These troupes had first appeared during the last decade of the nineteenth century; and in just two decades had popularized drama as a major entertainment form. Soon, many newly established companies were touring the presidency. Typical of a form that was trying to make its advent in a culture marked by orthodoxy, commercial drama companies had certain peculiarities initially: there were companies which employed only boys, and others, only women. Their repertoire was quite limited, mostly episodes from Indian mythology and their plays mere vehicles for songs, resembling European operas, and so the actors were required to be singers also. There grew a corpus of songs which enjoyed popularity on stage; and stage actors often gave independent concerts featuring these songs. The nascent gramophone record industry, together with the import of inexpensive gramophones from Japan, spread the appeal of these songs. In spite of such popularity, company dramas were looked down upon by the upper classes; artistes from these drama companies were treated like social outcasts by them.

The surge of anger that erupted all over the country over the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919 drew these entertainers into a vortex of political activity. With the print media coming under severely restrictive censorship, the stage became a convenient and relatively independent forum for mounting attacks on the policies of the British government. Songs from these plays spread the message of nationalism. Offstage, stage actors participated in demonstrations and pickets. Satyamurthi, recognizing the tremendous potential of the stage as a medium for nationalist propaganda, began to associate himself with this group. They, in turn, responded positively. One of Satyamurthi’s favourite statements from political platforms was: ‘We shall sing our way to freedom.’7

Stage artistes found themselves leading an active political life, acquiring in the process a new respectability which they had hitherto lacked. They found that they often appeared on political platforms along with nationalist leaders, a possibility they could scarcely have dreamt of earlier. This was an added incentive for their political activism. It must be noted here that political leaders had till then been dismissive and contemptuous of these artistes as people of no consequence. It was Satyamurthi who first established what had then seemed like an improbable nexus between political leadership and the world of popular entertainment.

One of the earliest links Satyamurthi forged among entertainers was with M M Chidambaranathan, an actor in company dramas who had been trained and inspired by the nationalist poet, Udumalai Sarabam Muthusamy Kavirayar. In 1921, when Satyamurthi led pickets in Madras as part of the Non-cooperation movement, Chidambaranathan organized many performances of patriotic plays. In addition to these propaganda efforts, he donated the gate collections for financing the demonstrations.8

Other troupes also began staging nationalist plays. When the British government imposed a ban on some of these troupes, Satyamurthi, who had by this time been elected to the Madras Legislative Council, raised the matter on the floor of the House. When neither the press nor the political leadership was prepared even to acknowledge the existence of these artistes, Satyamurthi, who advocated their cause, won their loyalty and they looked upon him as their spokesman and leader. From then on, he involved these artistes in all his political programmes. In 1928, when Satyamurthi was appointed the president of the Simon Boycott Propaganda Committee of the Tamil Nadu Provincial Congress to carry out an intensive campaign, his contact with the entertainers proved very valuable.9

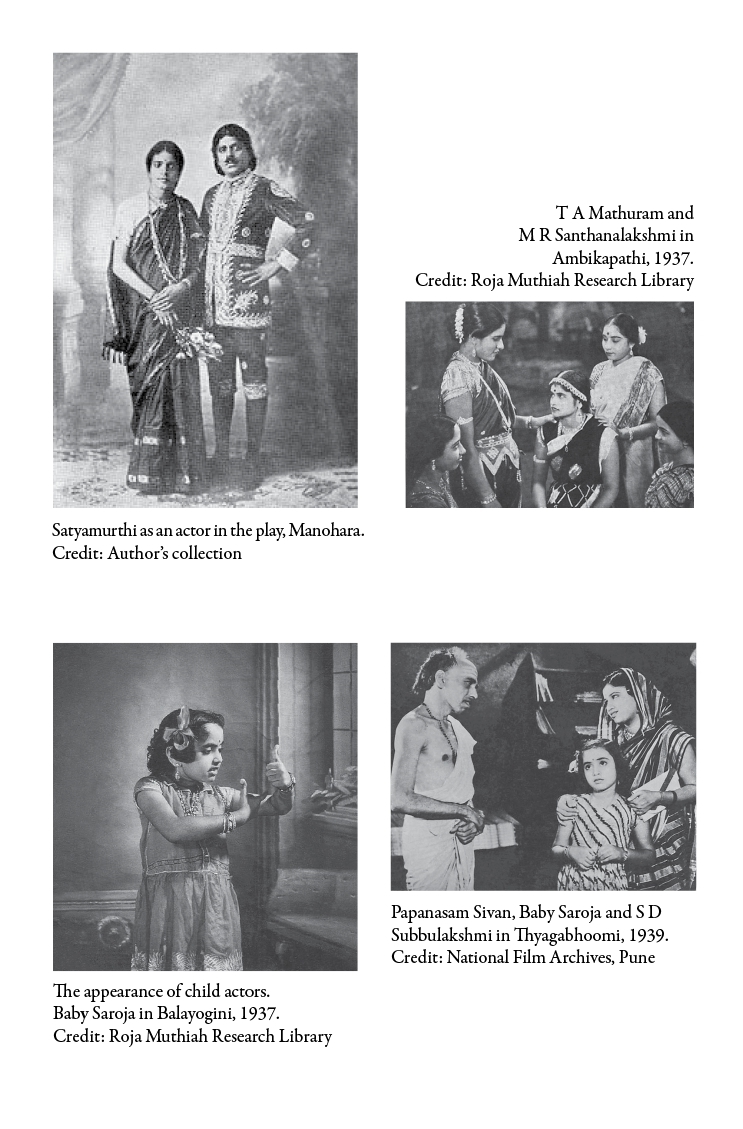

Gradually, Tamil talkies emerged as a popular entertainment form in the early 1930s, and artistes from the stage—playwrights, actors, song writers and musicians—moved en masse into the glittering world of cinema where the advent of sound had created a demand for their talents. Many well-known names from the stage quickly gained screen fame. When they entered cinema, they brought with them their repertoire of nationalist dramas and songs. The very first Tamil talkie Kalidas

had a song totally unrelated to the story of poet Kalidas, a song which extolled the charkha or the spinning wheel, a Gandhian symbol of nationalism. Soon, several films also began to be infused with nationalist propaganda.

Satyamurthi recognized the potential of cinema as an instrument of change and showed keen interest in its development. He used his powerful writing talent to promote the growth of cinema as a social force and predicted that cinema would play a major role in the next thirty years and that in a country with such high rates of illiteracy its influence was bound to be strong. In an article in a daily, he wrote, ‘I hope there will be a synthesis established between the film producers in India, the directors, and the leaders of the nation. The film should be made to comprise a purposeful part in Indian Renaissance.’10

When the film Nandanar

(1935) was released, he wrote about its implications for the Non-Brahmin movement, with whose protagonists he was engaged in a bitter political battle.11

Among the political leaders of India at that period, Satyamurthi had established a reputation for being fiercely independent. His association with film artistes was only one such factor which gave rise to this image. He openly opposed Gandhi in the All India Congress Committee meeting at Ahmedabad on 1 March 1930 and did not think that Prohibition was an important cause or that it should be given priority over other issues. He confessed in public his disillusionment with non-violence as a political weapon.12

Speaking at the meeting of the European Association in Madras on 20 May 1936, he was highly critical of socialism.13

When the Congress decided to resign from power in 1939 in protest against the war, Satyamurthi openly opposed the idea.

At a time when the educated elite despised cinema as a plebeian preoccupation and refused to consider it seriously, Satyamurthi, with great foresight, took pains to elucidate its importance. In 1939, in the Senate of Madras University, he pleaded for the introduction of cinema as a subject for study, but his idea was rejected, much to his anger and disappointment.14

He had hoped that the Indian film industry would be able to usher in an era of cultural swaraj (self-rule) and argued that educated women should join films and improve its quality. He was often invited to preside over the premiere of a film or to inaugurate a film’s shooting. When the film Iru Sakodarargal

(1936) was released in the Elphinstone cinema house in Madras, Satyamurthi was able to persuade a leader of Rajaji’s stature to attend the premiere show. The proceeds of this show went to the Patel Purse Fund. He also took note of the charisma these film actors were beginning to acquire; and he used it effectively.

Satyamurthi exercised considerable influence over film stars. Though cinema was looked down upon as low class entertainment, he could persuade classical musician Maharajapuram Viswanatha Aiyar to act in Asandas' classical film Nandanar.

16

While honouring the artistes of the film Thiruneelakantar,

Satyamurthi requested M K Thyagaraja Bhagavathar, the leading male star of the 1940s, to give up silk and wear only khadi; Bhagavathar readily deferred to this request.17

When a felicitation function was organized for the eminent actor-director Raja Sandow, it was Satyamurthi who was called upon to preside. He won over film actor

V Nagaiya to the nationalist cause and sent him as a delegate to the Congress session at Guwahati. All these artistes, in turn, lent their charisma in support of the party.18

However, Satyamurthi’s fascination with film stars at times went beyond their utility for propaganda efforts. He requested Gohar of Mumbai, a star of the silent era, to send him an autographed photo; she did, along with a note which said, ‘I will be greatly delighted to meet you whenever you come to Mumbai.’19

They did eventually meet in 1939, when Satyamurthi was in Bombay to participate in the silver jubilee celebrations of Indian cinema.

During the Civil Disobedience movement, with all the other leaders in jail, Satyamurthi found himself the president of the Council of Action.20

Many celebrities from the screen and stage now took part in direct political action. Dramatist Akkur Ananthachari was in charge of the movement in North Arcot district. Famous film artistes of the period like

K S Ananthanarayanan, who had acted in films like Alii Arjuna,

K S Devudu Aiyar (Radha Kalyanam

1935),

M V Mani (Sathi Leelavathi,

1936) and M G Nataraja Pillai21

(The Fire Sacrifice of Daksha/ Dakshayagnam,

1938) all participated in anti-government pickets and courted arrest. Filmmaker and founder of the first sound studio in South India, A Narayanan, a friend of Satyamurthi, lent his support to the movement and organized a bonfire of foreign textiles.22

K S Gopalakrishnan, actor-director (Jalaja,

1938) organized the All India Swadeshi Exhibition in Madras to subsidise the Salt Satyagraha campaign in Madras; he also conducted a music festival in which the great exponent of Carnatic music, Semmangudi Srinivasa Aiyar sang and renowned Bharatanatyam danseuse, T Balasaraswathi performed.23

By identifying themselves with such popular causes, these artistes increased their own popularity among the people.

Satyamurthi’s sustained interest and involvement in the world of cinema culminated in his election as the first president of the South Indian Film Chamber of Commerce in 1939 for a term of three years. It was he who drafted the Memorandum of Association and gave the organization its initial momentum.24

In the same year, he led a contingent from the Chamber to the silver jubilee celebrations of Indian cinema and the Motion Picture Congress at Bombay; he presided over the latter. In his address he declared, ‘The propaganda value, the technique and the appeal of the films will thus be the very best possible. It can in fact be made into a nation-building force in the true sense of those words. With popular governments and Congress governments functioning in the various provinces, there is unlimited scope.’25

He believed that cinema could be used to drum up mass support for the Congress and for tackling social problems like illiteracy.

Satyamurthi had a flair for election campaigns and from 1921 onwards, he insisted that the Congress should enter the legislatures. This was the plank of the Swarajists, a faction of nationalists with which Satyamurthi identified himself. He received financial assistance from C R Das and Motilal Nehru, which enabled him to start a newspaper and to build a cadre of publicists.26

One of Satyamurthi’s principal aims in contesting the elections was to displace the Justice Party, the genesis of Dravidian parties, from the legislature. When the 1935 Constitution brought in provincial autonomy and liberally expanded franchise, the need for using mass media in electoral campaigns was self-evident. He realized that in this changed scenario, film and stage artistes, with their unprecedented popularity, could be used effectively. Many well-known figures from the world of entertainment extended their support to the Congress in its campaign when the party decided to contest the elections in 1937. T K Shanmugam, the lead actor from one of the most successful troupes of the period, TKS Brothers Drama Company, and a film actor (Menaka),

campaigned for the Congress in the villages around Coimbatore. Their method of campaigning was to sing or make a political speech; their popularity as actors ensured that their very presence drew large crowds.27

The film artiste who played the most high profile political role was K B Sundarambal, the star of the film Nandanar

(1935). Influenced by her uncle, Marikozhundu Gounder, a Congress worker, Sundarambal joined the nationalist movement and became a close associate of Satyamurthi. Earlier, when she was reluctant to enter the world of cinema and was still mourning the death of her husband, stage-star S G Kittappa, it was Satyamurthi who persuaded her to sign the contract for the film Nandanar

(1935).28

Similarly, to persuade her to campaign for the Congress, Satyamurthi accompanied Gandhi during one of his visits to Madras to Sundarambal’s house.29

She campaigned hard for the Congress in the 1937 elections. The pattern followed was for her to sing patriotic songs first; which was followed by a speech by Satyamurthi. A gramophone record was also released with a song by Sundarambal on one side, which appealed to the voters to support the Congress, and a speech by Satyamurthi on the reverse side. Throughout her life, she wore only khadi and remained a loyal supporter of the Congress. In 1958 she was nominated as member of the Legislative Council in Madras.

Pioneer filmmaker A Narayanan made a short film supporting the candidature of Satyamurthi in Madras. The film, lasting a few minutes, featured Bhulabhai Desai and Satyamurthi appealing to voters.30

Thus Satyamurthi harnessed all the three popular entertainment forms—cinema, drama and gramophone—in widening and deepening political activism for the nationalist cause in Tamil society. In this process, the entertainers were brought under one flag and given a cause to work for. At a more practical level, Satyamurthi also pressed into service the most widely used contemporary media artefacts— songs, discs and film. Finally, these unorthodox instruments of electioneering proved quite successful. The Congress emerged victorious with a phenomenal majority in the Madras presidency; its margin of victory was not so decisive in the other provinces where it had won. Out of the 215 seats in the Madras presidency, Congress won 159.

In the Congress party, Satyamurthi acted as a bridge between the field worker and the top leadership. He observed the cultural experience of a vast majority of the people and thereby realized, with remarkable foresight, that popular culture was rapidly emerging as a force that could transform the political scene. The Congress leadership, on the other hand, refused to take cognisance of this development and treated the artistes with contempt as purveyors of cheap entertainment. This was one among the many ramifications of early elitist apathy to popular culture.

In spite of the support extended to the Congress by drama and cine artistes, the other leaders failed to appreciate the role played by these artistes in building up a strong, populist base for their party. Nor were they able to foresee the political dimensions cinema was to assume later. Gandhi, whose arrival on the scene marked the politicisation of the masses, failed to take note of the work of these artistes. His attitude to the entertainment media was typical of many Congress leaders. For its issue commemorating the 25th anniversary of cinema in 1938, a Mumbai film journal requested Gandhi for a message and received the following reply from his secretary, ‘As a rule, Gandhi gives messages only on rare occasions and these only for causes whose virtue is undoubted. As for the cinema, he has the least interest in it and one may not expect a word of appreciation from him.’31

Satyamurthi’s political rival in the Congress, Rajaji, who was seen to undermine Satyamurthi’s power base in Tamil Nadu, did not take kindly to the entertainment world which was so supportive of Satyamurthi.32

While the British government at the Centre and the Justice Party at the provincial level were targets of Satyamurthi’s attack, Rajaji was his chief rival within the Congress. Even in the early 1920s, when Satyamurthi had led a faction known as the Nationalists while Rajaji had headed the other faction, Satyamurthi had hoped to be chosen the prime minister of Madras province and was disappointed when he lost it to Rajaji. In their approach to the world of entertainment also, their opinions were diametrically opposed. Rajaji’s views on cinema were puritanical—as were his views on most other aspects of life—and he had asked people to refrain from watching films. In 1953, as chief minister presiding over a meeting of film celebrities, he described cinema as “poison” and said that if cinema could terminate itself, it would be an extraordinary service.33

Even K Kamaraj, a protege of Satyamurthi who succeeded Rajaji as the chief minister of Tamil Nadu, was quite disdainful of this group and contemptuously referred to them as koothadigal

(Mountbanks) .34

When Satyamurthi died in 1943, the leadership of the Congress in the Madras presidency passed on to Rajaji, his bitter political rival from the early years of his career.

While fighting the British government at the national level and at the provincial level, Satyamurthi was also constantly trying to out-manoeuvre the Justice Party, the ideological forerunner of the Dravidian parties, and he managed to keep it at bay. As long as he was active, they could not make much headway in the face of his campaigning skills. As mentioned earlier, his principal objective in persuading the Congress to enter the legislature was to evict the Justicites. He fought the Justice Party in the 1926 elections for the provincial council and defeated it, bringing to an end the first six years of its rule in Madras. The Justice Party’s opposition to the Congress, was because it feared that if the British handed over power to that party, it would only perpetuate the dominance of Brahmins in the province.35

Satyamurthi had consistently opposed all that the Justice Party and the later the Self-respect movement had stood for. He, who had studied Tamil only up to fourth standard in school, believed that Sanskrit should be accorded a prime place in education and declared that he looked forward to the day when Hindi would be the national language. He was orthodox in religious matters and believed in astrology and horoscopes. He advocated early marriage for women recommending that about fifteen years was the ideal age, and opposed inter-caste marriage.36

He therefore clearly took a position against the efforts that were on in the province to establish a Dravidian identity. 37

After his death, artistes from the world of entertainment, now leaderless and directionless, gravitated towards the Dravidian movement, whose leaders offered them recognition and patronage. In fact, many of the leading lights of the movement, including C N Annadurai and M Karunanidhi, were themselves playwrights and often acted in plays. It was they, the Dravidian leaders, and bitter political enemies of Satyamurthi, who eventually inherited the force that he had assiduously nurtured, and used it in their journey to power, creating the phenomenon of star-politicians.

The Dravidian movement, which was then expanding its mass base, first began using the stage for propaganda, with many artistes joining the movement. Later, when Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam was formed in 1949, stage and film artistes also came in handy as tools for propaganda; the party’s first organizing committee included K R Ramasamy, a film star, and T V Narayanasamy, a drama actor. N S Krishnan, yet another actor was also one of the main supporters of the party.38

In fact, the career of N S Krishnan, who dominated the Tamil film scene for more than two decades as a comedian and acted in more than a 100 films, epitomizes the fortunes of stage and screen artistes in the political arena during that crucial period in history. Since the time of the Civil Disobedience movement, Krishnan had been actively carrying on political propaganda for the Congress. He wrote the story of Gandhi’s salt satyagraha as a villupaatu

, a traditional form of musical narration, and performed it as a part of Swaminatha Sarma’s famous play Desabakthi,

and later, as a separate show. After Independence, for the first general election in 1952, Durgabai Deshmukh persuaded him to contest as a Congress candidate from Madras. When Krishnan was in Delhi to finalise his candidature, some Congress leaders from Madras ridiculed the idea, saying that a komali

(clown) should not enter the legislature. Piqued, Krishnan refused to contest.39

In the 1952 general elections, N S Krishnan, along with actor

M R Radha and K R Ramasamy, campaigned against the Congress candidates.40

Later, he lent his support to the Dravidian movement and was of invaluable assistance in building up the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, though he was never a member of that party. S S Rajendran, a lead player of the nationalist TKS Brothers Drama Company, joined the DMK and became the first film star to be elected to a legislature when he won the election to the Tamil Nadu Assembly in 1962 from the Theni constituency.Later, he also became a Member of Parliament.

M G Ramachandran, the best known star-politician of the Dravidian movement, had acted in the nationalistic play The Triumph of Khadi/Kadarin Vetri

as a company drama artiste and was a khadi-wearing Congress sympathizer before he joined the DMK.

Notes

This chapter is based on an article of the same tide, published in

The Economic and Political Weekly,

Vol.XXIX, No. 38 (1994).

1. The building housing the headquarters of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee in Madras is called Satyamurthi Bhavan, largely due to the efforts of K Kamaraj.

2. Parthasarathy, R,

S. Satyamurthi

(Builders of Modern India series) (New Delhi, Publication Division, 1979) pp 193-201.

3. See Satyamurthi, S, “Mrichakatika—A Sanskrit Drama”, in

Indhunesan,

Annual (1923).

4. Parthasarathy, S,

Satyamurthi,

p.62

5. Satyamurthi Papers, Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi.

6. Copley, Anthony,

C.Rajagopalachari: Gandhi’s Southern Commander

(Madras, Indo-British Historical Society, 1986) p.74.

7. Parthasarathy, S,

Satyamurthi

, p.196.

8. Chidambaranathan, M.M., “

Sudhanthira Poratathil

Kalaignargal

” in

Nadigan Kural

(Tamil) August 1957.

9. Visswanathan, E Sa,

The Political Career of E.V.Ramasami Naicker: A Study in the Politics of Tamil Nadu. 1920-1949

(Rau & Vasanth Publishers, Madras, 1983) p. 118.

10.

The Mail

(Daily

),

26

December 1936.

11.

Cinema Ulagam

(Tamil), 11 August 1935.

12. Copley,

C.Rajagopalachari,

p.99 and p.143.

13. Parthasarathy, S,

Satyamurthi

, p.181-182.

14.

Film Gazettee,

Vol.1, No.2, December 1939.

15.

The Hindu,

8 January 1937.

16.

Cinema Ulagam,

21 April 1935.

17.

Dinamani Kadir

(Tamil), 27 May 1990.

18.

Dinamani Kadir,

9 February 1973.

19.

Satyamurthi Papers,

Letter dated 26 December 1928 from Gohar to Satyamurthi.

20. Parthasarathy, S,

Satyamurti,

p.94

21. Known as “Salt Satyagrahi Nataraja Pillai”, a street has been named after him in his home town Mannargudi.

Adal Padal

(Tamil), 3 June 1939.

22. Dr N Kalavathy (daughter of A Narayanan), interviewed by the author in Madras, 25 April 1976.

23. This incident paved the way for the founding of Music Academy. K S Gopalakrishnan interviewed by the author in Madras , 19 January 1976.

24. Lakshmi Krishnamurthy (daughter of Satyamurthi), interviewed by the author in Delhi, 27 March 1986.

25. Indian Motion Picture Congress, Presidential address, (Pamphlet) Mumbai, 7 May 1939.

26. Baker, Christopher,

The Politics of South India 1920-1937,

(London, Cambridge University Press, 1978) p. 158.

27. Shanmugam, TKS

Enadhu Nataka Vazhkai,

(Madras, Vanadhi Pathipagam, 1972) p. 135.

28. K B Sundarambal interviewed by the author in Madras,

9 April 1975.

29. Kumari Anandan in

Kumudam

(Tamil), 9 May 1991.

30. P G Sundararajan alias Chitti (Tamil writer and associate of Satyamurthi) interviewed by the author in Madras,

28 April 1975.

31. Dogra, Bharat B, “When the Censors Tried to Block Out the Congress”,

Filmfare,

27 July 1975.

32. Copley,

C.

Rajagopalachari,

p.147. For a detailed account of the Rajaji-Satyamurthi rivalry, see Copley’s book.

33. Bamouw, Eric, and S Krishnaswamy,

Indian Cinema

(New York, Oxford University Press, 1963) p. 176.

34. Pandian, M S S,

The Image Trap,

(New Delhi, Sage Publications, 1992) p.38.

35. Sattanathan, A N,

The Dravidian Movement in Tamil Nadu and its Legacy,

(Madras, University of Madras, 1982) p.14.

36.

Satyamurthi Pesugirar

(Tamil, collection of speeches), (Madras, Thamizh Pannai, 1945) see chapters “

Namadhu Latchiyam

”

(Our Goal) and “

Indhu Vivaham

”(Hindu Marriage).

37. Irschick, Eugene F,

Politics and Social Conflict in South India: The Non-Brahmin Movement and Tamil Separatism, 1916- 1929,

(Berkley, University of California Press, 1969) p.249.

38. In his last public function as chief minister, in 1969, C N Annadurai unveiled a statue of N S Krishnan, in an important road junction in Thyagaraya Nagar in Madras.

39. Subrahmanyam, K, “

Viruppum Veruppum Atra

Kalaivanar

” in

Kalaivanar Malar,

Souvenir marking the 13th death anniversary N S Krishnan (Madras, 1968).

40. Sivagnanam, Ma Po,

Enadhu Porattam,

(Madras, Inba Nilayam, 1974) p.559.