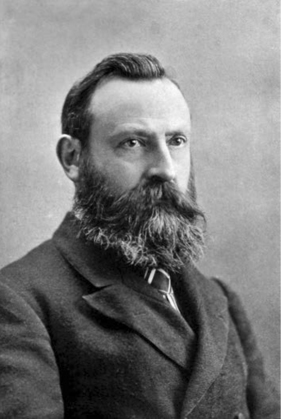

William Wynn Westcott (1848–1925) was a gentle, friendly man, born in Crowley’s hometown of Leamington. His life was like two parallel streams, flowing side by side but never crossing. One river was the medical profession, the other his spiritual journey. His father, the surgeon Peter Westcott of Oundle, died when Wynn was about ten, and he was subsequently raised by his uncle, Dr. Richard Westcott Martyn of Martock, Somerset. Following in the footsteps of his family, Westcott attended University College, London, passing the University of London’s second division MB exam in 1869, and on April 14, 1870, passing his exam at Apothecaries’ Hall to receive a certificate to practice medicine. 1 By age twenty-three—four years before Crowley was born—he became a partner in his uncle’s medical practice in Martock, Somersetshire. Shortly thereafter, he married Eliza Burnett (c. 1851–1921), with whom he had five children. 2 Beginning around 1883 he held the post of deputy coroner for central Middlesex and central London until he was appointed coroner of northeast London in 1894. 3 In this capacity, he held over twenty-one inquests per week into deaths reported in his region 4 until his 1918 retirement. His professional service included stints as president of the Society for the Study of Inebriety, vice president of the Medico-Legal Society, vice president of the National Sunday League, and councillor of the Coroners’ Society. Although he published professionally—authoring the book Suicide: Its History, Literature, Jurisprudence, Causation, and Prevention (1885) and the paper “Twelve Years’ Experience as a London Coroner” (1907) and coediting fifteen editions of The Extra Pharmacopoeia from its original 1883 publication 5 —the bulk of his literary output concerned the occult.

Hermetic philosophy always fascinated Westcott, leading him to study kabbalah, alchemy, and Rosicrucianism. These pursuits led him in 1871—about the time he partnered with his uncle—to join the Parrett and Axe Masonic Lodge, over which he would preside as Worshipful Master in 1877. He also pursued the higher degree rites of Freemasonry, advancing to the Royal Arch and the Rose Croix degrees in 1873 and by 1878 reaching the thirtieth degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite. 6 On December 2, 1886, he was admitted to the prestigious Masonic research lodge, Quatuor Coronati; seven years later, in 1893, he was unanimously elected and installed in a one-year term as its master. 7

Dr. W. Wynn Westcott (1848–1925), cofounder of the Golden Dawn. (photo credit 3.1)

Westcott also joined other initiatory organizations, both allied and irregular. On January 7, 1880—just before becoming Deputy Coroner—he joined London’s prestigious Rosicrucian fraternity, Societas Rosicruciana in Anglica (SRIA). He served as Supreme Grand Secretary of the Swedenborgian Rite, a hermetic revival of an earlier fraternal order based on the teachings of Christian mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772). And he joined the Esoteric Section of H. P. Blavatsky’s (1831–1891) Theosophical Society (TS). The results of his scholarly research into hermeticism took the form of several dozen contributions to Masonic journals Ars Quatuor Coronatorum and The Freemason , to the Transactions of the Metropolitan College of the SRIA, and to Theosophical journals The Theosophist, Lucifer , and Theosophical Siftings . He also wrote books like Numbers: Their Occult Power and Mystic Virtue (1890), translated the Sepher Yetzirah (1893) and The Magical Ritual of the Sanctum Regnum (1896) into English, and cowrote and edited a series of ten monographs issued by the TS as Collectanea Hermetica (1893–1896). 8

In 1887, Westcott discovered in the musty SRIA library an old manuscript written in cipher. Decoding its contents, he discovered ritual fragments and the address of Fräulein Anna Sprengel, a German Rosicrucian adept. Writing her, he was surprised to receive authorization to start an English branch of the esoteric school known as “Die Goldene Dämmerung,” thus marking the inception of the Golden Dawn (GD), the organization that counted England’s intelligentsia amongst its members. This, at least, is the legend.

Whatever the origin of the Cipher Manuscript, the Isis-Urania branch (or, formally, Temple) of the GD was founded in 1888. Like the other societies he had encountered, the GD espoused no particular religious belief, merely transmitting knowledge gained from comparative study of religion and philosophy the world over. Westcott invited two SRIA associates—W. R. Woodman and Samuel Liddell Mathers—to form the ruling triumvirate.

Dr. W. R. Woodman (1828–1891) was a retired physician twenty years Westcott’s senior. He had also studied kabbalah, Egyptian antiquities, gnosticism, philosophy, astrology, alchemy, and tarot. Having begun as SRIA’s secretary in 1867, he advanced in eleven years to the post of supreme magus. Upon his death in 1891 (three years after founding the GD), Westcott would succeed him as SRIA’s head.

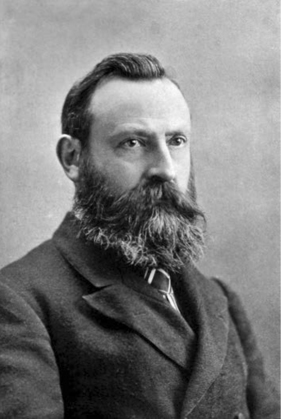

Samuel Liddell Mathers (1854–1918) was the most colorful of the GD’s founders. Born in Hackney, he was the son of commercial clerk William M. Mathers. His father died young, and his mother raised him alone at Bournemouth. After her death in 1885 he moved to London. As an adult he maintained a firm athletic build from boxing and fencing. He also spent countless hours in the British Museum reading room, studying both magic and warfare. He joined the SRIA around 1877, where he met both Woodman and Westcott. In 1887—while Westcott was reputedly deciphering the Cipher Manuscript—he published The Kabbalah Unveiled , a translation of Christian Knorr von Rosenroth’s treatise on the Zohar, Kabbala Denudata (1677–1684), prefaced with his own exposition on the subject. He dedicated the book to Anna Kingsford (1846–1888), past president of the London TS and one of the first English women to obtain a degree in medicine; highly influenced by her and her book The Perfect Way (1882), Mathers became a staunch vegetarian and anti-vivisectionist. 9 At the reading room, Mathers made two friends who would become major players in the GD saga: Mina Bergson and W. B. Yeats.

Mina Bergson (1865–1928) was the younger sister of Nobel Prize–winning philosopher Henri Bergson (1859–1941). 10 A sweet, attractive woman with springy hair and blue eyes, she was a London art student by age fifteen. She met Mathers in 1888 while studying Egyptian art at the British Museum. The mysterious scholar, eleven years her senior, fascinated her, and they wed two years later. She called him Zan, after the protagonist in Bulwer-Lytton’s mystic novel Zanoni (1842). He called her Moïna, his Highland redaction of her name.

William Butler Yeats (1865–1939) placed mysticism second in his life only to poetry. By 1887 he had joined Kingsford’s Hermetic Students and, between 1889 and 1890, organized the Esoteric Section of the TS. He met Mathers in the British Museum reading room around 1889, and came to idolize the man he later characterized as having “much learning” but “little scholarship.” 11 Yeats split with the Theosophists because they discouraged the practice of magic; on March 7, 1890, he joined the GD.

Golden Dawn cofounder Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers (1854–1918) in 1911. (photo credit 3.2)

After losing his job in London and moving to Paris with his wife, Mathers became increasingly eccentric. Rekindling his childhood love of Celtic symbology, he adopted all its trappings: He claimed descent from the clan MacGregor, the name of which had been suppressed under penalty of death and in 1603 changed to Mathers. He adopted pseudonyms like Comte de Glenstrae, Comte MacGregor, and Samuel Liddell MacGregor; rode his bicycle through the Paris streets in full Highland dress; and reputedly performed the sword dance with a knife in his stocking. Back in London, rumor had it Mathers believed himself to be the reincarnation of Scottish wizard king James IV.

That same year, Woodman died; with Westcott succeeding him as supreme magus of the SRIA, he essentially became a silent partner in the GD. This left Mathers as de facto head of the order, and he seized the opportunity to assert his dominance, claiming direct contact with the Secret Chiefs—those mysterious and disembodied masters who ran the order—and managing the London temple from Paris.

When high-ranking members tired of answering to an invisible hand, Mathers responded with a pronunciamento dated October 29, 1896: the Secret Chiefs had appointed him supreme ruler of the GD; as such, Mathers demanded all members sign and return to him an oath of loyalty. He would meet all refusals with expulsion.

Ousted in the shakedown was high-ranking member Annie Horniman. The wealthy daughter of a tea merchant, her £200 annual stipend to Mathers was the only thing standing between his obscure translations—such as The Sacred Book of Abramelin the Mage —and poverty. The expulsion, of course, meant the end of his allowance. Many of the London temple’s 323 members were outraged by Horniman’s suspension and assembled a petition to reinstate her. Mathers refused to yield.

Coincidentally, matters forced Westcott to further distance himself from the GD at this time. Within days of Mathers’s last visit to London, Westcott’s employers confronted him: someone (in retrospect, presumably Mathers or an ally) had left a GD instructional paper on a carriage with Westcott’s name and business address on it. Learning of Westcott’s outside interests, his superiors told him, “A coroner should bury bodies, not dig them up.” Westcott gladly pulled back from the order, finding Rosicrucians much easier to deal with than ceremonial magicians.

In this agitated political environment, Crowley found himself a Neophyte.

A member of that ages-old college of occultism described by Eckartshausen, Perdurabo set out to learn all he could. Upon entering the grade of Neophyte (cryptically denoted 0°=0°, where the first digit represented the grade and the second digit the corresponding position on the Hebrew Tree of Life), he discovered that, like any other school, the GD contained grades through which students passed after examination. Four grades awaited: the Zelator (1°=10°), Theoricus (2°=9°), Practicus (3°=8°), and Philosophus (4°=7°); then he would enter the Portal grade to the mysterious Second Order.

His first lessons as an occultist gravely disappointed him. They were neither new nor arcane. His teachers asked him to learn the Hebrew alphabet, the 10 spheres or sephiroth of the Hebrew Tree of Life, and the attribution of the seven planets to the seven days of the week. The secrets he swore to keep inviolable were trivia he had already known for months, gleaned from countless other books of magic. Jones and Baker were supportive, advising him not to judge the GD until he reached the Second Order.

Equally disappointing was the order’s membership. Expecting to encounter spiritual giants, he discovered a group of nonentities. Crowley was not alone in this opinion. GD member and Irish feminist Maud Gonne (1866–1953) characterized the order as “the very essence of British middle-class dullness. They looked so incongruous in their cloaks and badges at initiation ceremonies.” 12 Even Jones called it “a club, like any other club, a place to pass the time and meet one’s friends.” 13 Despite these views, the GD attracted its share of luminaries. Over the years, it claimed among its membership authors Arthur Machen (1863–1947) and Algernon Blackwood (1869–1951); the aforementioned poet W. B. Yeats and his uncle George Pollexfen; and Constance Mary Wilde (1859–1898), wife of Oscar Wilde. In addition to these better-known names, the GD also hosted men of learning, including chemists (Baker and Jones), physicians (Westcott, Woodman, Bury, Berridge, Felkin, and others), and occult scholars (Waite, Mathers, Bennett). In 1898, Dr. Bury even invited Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930) to join, but he declined.

Despite his protestations, Crowley’s initiation deeply impressed him. He wrote the poem “The Neophyte” 14 about the experience and, like Yeats, would forever after show its influence in his writing and life.

Jezebel and Other Tragic Poems (1898) 15 was a twenty-three-page booklet with a vellum wrapper, privately printed at the Chiswick Press with twelve copies on vellum and forty on handmade paper. Published under his Russian pseudonym of Vladimir Svareff, 16 it featured an introduction and epilogue by Aleister Crowley and a dedication to his Cambridge friend Gerald Kelly.

While Crowley had an excellent printer in the Chiswick Press, he had no way to distribute and sell his books. Smithers introduced him to the London firm of Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Company, printers and booksellers, and he chose them to sell his next book, Tale of Archais (1898). Appearing in January 1899, the edition consisted of one hundred copies which sold for five shillings apiece. One-fourth of the print run was sent out for reviews, which ranged from “a certain command of facile rhythm” to “spurious romanticized mythology.” 17 As early as 1905, Crowley regretted publishing the piece. 18 Later, Crowley recalled it as “simply jejune; I apologize.” 19

Songs of the Spirit (1898) continued Crowley’s association with Kegan, Paul, Trench, Trübner and Company. Although Crowley contracted this edition around December 1898, it appeared after Tale of Archais . Finishing at 109 pages, AC dedicated the volume to Julian L. Baker in gratitude for introducing him to the GD. He issued one copy on vellum and fifty signed, besides the print run of three hundred. This mixed bag of poems, largely dating from 1897, garnered mixed reviews from the press. While the Manchester Guardian admired its intense spirituality and technical superiority, the Athenaeum considered it to be “difficult to read, and where they touch definite things, more sensual than sensuous.” 20 The Outlook called Crowley “a poet of fine taste and accomplishment” and his book “contains much that is beautiful.” 21 By the end of the year, half the print run had sold.

Realizing how easy it was to publish his poetry, Crowley continued turning it out as quickly as the presses could print it.

A cold chill filled the room, but not because it was January. Magical energy charged the temple, but not because of the ritual. No, it was that haggard man with dark wild eyes that put everything out of sorts. AC didn’t know who he was but felt his unsettling energy throughout the ceremony. Crowley anxiously disrobed in the changing room, anticipating a lungful of open air.

As he adjusted his floppy silk bow tie, his heart pounded with the sound of approaching footsteps. The man pierced him with his eyes. He had a thick brow and an almost fanatical gaze. If not for his pallor and the physical suffering exuded by his presence, he might have been handsome. For now, Crowley found him intimidating. “Little Brother,” he observed, “you have been meddling with the Goetia .”

Crowley stared into his burning eyes, transfixed. “No, I haven’t.” It was a lie. He had been playing with magical tomes like Abramelin and the Goetia or Key of Solomon ever since he moved into his Chancery Lane flat. Just the other night, he and Jones watched as semimaterialized figures and shadows paraded endlessly around the temple.

“In that case,” the man continued, “the Goetia has been meddling with you.” Then he was gone again.

The figure was Frater Iehi Aour (“Let there be light”), affectionately known as the White Knight after Through the Looking-Glass . GD members ranked him second only to Mathers as a magician. They told the story of how, at a party, someone ridiculed the notion of a blasting wand as described in medieval texts on magic; Iehi Aour took offense, produced a long glass prism, and pointed it at the offender. Fourteen hours later, doctors revived the skeptic.

Other gossip described an altercation about Hinduism between Mathers and Iehi Aour. Mathers had rejected Frater IA’s contention that, by calling upon Shiva, one could cause the god to open his eyes and thereby destroy the world. To prove his point, IA plopped down on the floor of Mathers’s living room in lotus position and began chanting, “Shiva, Shiva, Shiva …” Mathers, already agitated by the argument, stormed out of the room. Returning half an hour later to find his guest still at it, he erupted, “Will you stop blaspheming?” The mantra continued. Mathers drew his revolver. “If you don’t stop, I’ll shoot you.” The mantra continued. Moïna entered the room just in time to end the argument, saving not just the White Knight but also the universe.

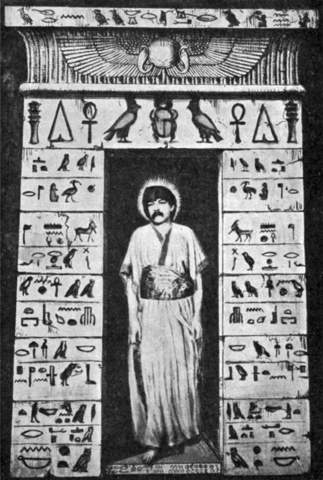

The man behind the legend of Frater Iehi Aour was Allan Bennett (1872–1923). Born Charles Henry Allan Bennett during the Franco-Prussian war, his widowed mother raised him a strict Catholic. According to Crowley, he led a sheltered life, still believing at age sixteen that angels brought babies to earth. When classmates showed him an obstetrics manual, he found the facts of human reproduction so offensive and degrading that he lost faith in a benevolent God and abandoned Catholicism. At eighteen he briefly experienced the yogic trance of Shivadarshana , wherein the entire universe is united and all sense of self annihilated. Although he knew nothing of yoga, the vision was so profound that he vowed, “This is the only thing worth while. I will do nothing else in all my life but find out how to get back to it.” Thus he dedicated himself to the study of Buddhist and Hindu scriptures. By 1894 he had joined the GD and performed many legendary ceremonies. In one of these, he created a talisman for rain that required water to work; he lost it in a sewer, and London had one of the wettest summers on record. By twenty-five his magical prowess was renowned throughout the order.

Allan Bennett (1872–1923), Frater Iehi Aour. (photo credit 3.3)

Like Baker and Jones, he was an analytical chemist. He was tall, but asthma had reduced him to a stoop. Opium, morphine, cocaine, and chloroform each rotated for two months as his antihistamine and inadvertently showed him the ability of certain drugs to open pathways to higher consciousness.

Crowley was stunned to find Bennett living in a south London tenement with Charles Rosher, GD member, inventor, sportsman, and jack of all trades. Such a great scholar ought not to live in squalor, Crowley believed. Realizing that Bennett could teach him more in a month than anyone else could in five years, he proposed a solution: since he needed a teacher and Bennett needed a benefactor, the White Knight could share Crowley’s flat in exchange for lessons in magic. Bennett accepted, and under his tutelage, Crowley progressed rapidly. Possessing all the order’s papers, Bennett provided his acolyte with a preview of the material he would receive. He also demonstrated his infamous wand:

With this he would trace mysterious figures in the air, and, visible to the ordinary eye, they would stand out in a faint bluish light. On great occasions, working in a circle and conjuring the spirits by great names … he would obtain the creature … in visible and tangible form. On one occasion he evoked [the angel] Hismael and through a series of accidents, was led to step out of the circle without effectively banishing the spirit. He was felled to the ground, and only recovered 5 or 6 hours later. 22

In private moments Bennett insisted, “There exists a drug whose use will open the gates of the World behind the Veil of Matter.” This introduced Crowley to the controlled use of drugs for mystical purposes.

Theirs was one of the strongest friendships Crowley would ever know. He always spoke of Bennett with great respect. “There never walked a whiter man on earth,” Crowley described him. “A genius, a flawless genius.” 23

In the months following his initiation, Crowley advanced steadily through the GD’s grades, graduating to Zelator in December 1898; Theoricus in January 1899; and Practicus in February. After an obligatory three-month interval, Frater Perdurabo reached the highest grade in the GD’s hierarchy, Philosophus, in May 1899. He stood at the gates of the Second Order, where the great secrets of magic awaited. Soon he would advance to the Portal.

It was time he met the head of the order, known in the First Order by the motto Frater ’S Rioghail Mo Dhream (“Royal is my tribe”), in the Second Order as Frater Deo Duce Comite Ferro (“With God as my leader and the sword as my companion”), and, in the mundane world, as Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers. He and Crowley shared many common interests. Both were athletic. Both basked in the romance of the Celtic revival, inventing romantic lineages for themselves; Mathers of the clan MacGregor and Crowley from the family O’Crowley. Both were driven by aspirations to spiritual greatness, and both were scholars of recondite wisdom. Mathers saw great potential in Crowley and approved of Bennett’s accelerated instruction.

By summer, Crowley was notorious in the order.

In befriending Bennett and Mathers, he inspired suspicion, uneasiness, and envy among senior members. The best magicians in the order had taken him under their wings. Crowley was sharp, moving easily and briskly through the grades, and grew arrogant about his aptitude. Bennett, although respected, was also a figure of awe and, to some, fear; thus Crowley’s tutelage under the White Knight seemed darker still. Moreso, Perdurabo’s friendship with Mathers allied him in a camp where loyalties were quickly dividing. Mathers was increasingly viewed as a despot, and Crowley became guilty by association.

Part of his bad reputation traced to his friendship with Elaine Simpson (b. 1875), known in the order as Semper Fidelis (“Always faithful”). Born in Kussowlie, West Bengal, she was the daughter of Rev. William Simpson and Alice (née Hall); Elaine’s grandfather was Sir John Hall (1824–1907), the prime minister of New Zealand from 1879 to 1882. Alice Simpson was born in Mahableshwar, India; the family’s temporary move to Germany during the 1860s “laid the foundation of the training in music and languages which enabled her later in life to become a musician of repute and a linguist of considerable fame.” 24 In 1873 she married Rev. Simpson of the Indian Anglican Ecclesiastical Establishment, living with him for some time in India. The Simpsons had two daughters: Elaine was the eldest, while the younger daughter, Beatrice, would move to New York, where she would establish herself as an actress and poet under the stage name Beatrice Irwin. 25 Both Alice and Elaine belonged to the order; although Crowley found Elaine charming, he had nothing nice to say about her mother, whom he described as “a horrible mother, a sixth-rate singer, a first-rate snob, with dewlaps and a paunch; a match-maker, mischief-maker, maudlin and muddle-headed.” 26 The hard feelings stem from a rumor spread by Mrs. Simpson that Crowley had visited her daughter’s bedroom at night in astral form. Both Aleister and Elaine denied the charge (but a few years later it inspired an experiment between them).

Finally, even Crowley’s lifestyle fell under scrutiny. The older, staid members believed that a magician should abstain from sex, drink, and drugs to keep his mind clear, and Crowley’s libertine ways went against the grain on all counts. Under Bennett’s guidance, he drank and took all manner of drugs—the members could only guess which ones. And his promiscuity quickly became legend: gossip linked Crowley not only to Elaine Simpson but also to the Praemonstrix (acting head), Florence Farr, and even Bennett himself. Still others suggested that “he lived under various false names and left various districts without paying his debts.” 27

Yeats and Crowley should have gotten along, considering how much they had in common: the Celtic revival, magic, Decadence, and poetry. 28 However, Crowley’s notoriety made him a difficult figure for Yeats to embrace when they met in the summer of 1899. As Crowley’s friend Gerald Yorke later recalled,

Crowley objected to Yeats on the grounds that he had deserted the Great Work for literature. Yeats of Crowley that he had prostituted the Great Work and was a ‘Black Magician.’ Both verbally to me. I think they were both mistaken, but both had fairly legitimate reasons for their opinion. 29

Instead of becoming friends, circumstances made them rivals in three areas dear to their hearts: love, magic, and poetry.

If there is but one iota of truth to the contention that they were rivals in “at least one romantic affair” 30 —Florence Farr—this alone could have made them mortal enemies. Florence Beatrice Farr (1860–1917) was an early GD friend of Crowley’s, possibly through the astral projection study group she ran. The daughter of a successful doctor, she abandoned college at age eighteen to pursue an acting career. After an unsuccessful marriage to Edward Emery, she became George Bernard Shaw’s (1856-1950) mistress in 1889. She joined the GD a year later and, attracted to Yeats, found herself torn between two loves: Shaw and Yeats, drama and magic. She chose magic, attaining prominence in both the GD hierarchy and Yeats’s affections. Crowley possessed “affectionate respect tempered by a feeling of compassion” 31 for her. Farr’s biographer maintains that, while “There is no doubt that Florence and ‘The Beast’ … shared some sort of rapport for a short while,” 32 they were not romantically linked.

Another rivalry—magic—posed an obstacle to friendship with Yeats. Long a close friend of Mathers, Yeats visited him and exchanged friendly correspondence after his move to Paris. Suddenly, a brash young upstart arrived, apparently brownnosing the order’s head. At the very least, Crowley became the friend to Mathers that Yeats felt he should have been.

If Crowley is to be believed, Yeats was also jealous of his talent as a poet. While correcting the proofs to Jephthah; and Other Mysteries, Lyrical and Dramatic (1899), Crowley asked Yeats his opinion of the piece. Looking it over, Yeats replied politely, but Crowley detected rage and jealousy in his reply. If the critics are right, Crowley may have been somewhat correct: most reviewers received Jephthah with praise. The Manchester Guardian wrote, “If Mr. Swinburne had never written, we should all be hailing Mr. Aleister Crowley as a very great poet indeed,” while the Aberdeen Journal thought “He has caught the spirit in the style of Swinburne, and in some respects the pupil is greater than his master.” 33 The Outlook effused:

Mr. Aleister Crowley possesses uncommon gifts. As behoves a person so blest, he devotes himself to poesy. And there is no department of the sad mechanic exercise in which he fails of a kind of mastery. That is to say, his blank verse is almost unexceptionable; he will rhyme you fair sound rhymes from now to Candlemas; he is good at your strophe, your antistrophe, your chorus, your semi-chorus, your sonnet, your ode, your set of verses of all lengths; and he can build a pleasure-house of sweet words upon the inane. 34

Nevertheless, it would be Yeats, not Crowley, who would go on to win a Nobel prize for literature.

Regardless of the reasons, these rivals in matters of love, magic and poetry strongly disliked each other. Yeats admitted Crowley was handsome, but suspected he was mad. “[W]e did not think a mystical society was intended to be a reformatory,” he wrote of Crowley. 35 As a poet, Yeats felt Crowley had “written about six lines, amid much foul rhetoric, of real poetry.” 36 Meanwhile, Crowley gave Irish writer George Moore (1852–1933) a book with the inscription: “You write of Yeats as ‘a poet in search of a pedigree’—but who told you he was a poet? Read ME!” 37

Accusations of black magic finally emerged from this rivalry. Crowley describes one incident in “At the Fork in the Roads” (1910): 38 During the summer of 1899, AC was visited by Irish poet and artist Althea Gyles (1867–1949), who had drawn the cover of Yeats’s The Secret Rose (1897), Poems (1899), and The Wind among the Reeds (1899) 39 and whose work Yeats praised:

Miss Gyles’ images are so full of abundant and passionate life that they remind one of William Blake’s cry, “Exuberance is Beauty,” and Samuel Palmer’s command to the artist, “Always seek to make excess more abundantly excessive.” One finds in them what a friend, whose work has no other passion, calls “the passion for the impossible beauty” … [H]er inspiration is a wave of a hidden tide that is flowing through many minds in many places, creating a new religious art and poetry. 40

Despite being perceived as naive and spiritual—even Crowley remarked on “her steely virginal eyes” 41 —she was also working, and having an affair, with Leonard Smithers, much to the chagrin of her friends. Mackenzie, in her thinly disguised novel about Gyles, wrote that she,

after treating reasonable admirers with prudish contempt, had fallen into the arms of an abominable creature of high intelligence, no morals, and the vivid imagination which was perhaps what she had been waiting for. He had the worst of reputations even among the Paris set. Ariadne lost caste, and when the affair ended after more than a year of heady intoxication, and with a certain amount of inspired work, she collapsed. 42

According to “At the Fork in the Roads,” after a discussion on clairvoyance, Gyles put on her coat to leave and, in so doing, inadvertently scratched Crowley with her brooch. The next day, when Crowley awoke feeling weak, Gyles admitted that Yeats was using black magic to destroy him. With Crowley, distinguishing fact from fancy in his fiction is nearly impossible; when he calls the account true in “every” detail, the claim wants for caution. It is unlikely Gyles gave Crowley such a confession; if she did, we don’t know if it was volunteered or extracted. Regardless, enough happened for Crowley to write of himself (in the third person):

His house in London became charged with such an aura of evil that it was scarcely safe to visit it. This was not solely due to P[erdurabo]’s own experiments; we have to consider the evil work of others in the Order … who were attempting to destroy him. Weird and terrible figures were often seen moving about his rooms, and in several cases, workmen and visitors were struck senseless by a kind of paralysis and by fainting fits. 43

Similarly, Yeats claimed “Crowley has been making wax images of us all, and putting pins in them.” 44

Neither one of them imagined a real magical war would soon begin.

“As life burns strong, the spirit’s flame grows dull,” Crowley wrote in his first book. Now the life flame of his spiritual beacon Allan Bennett was wracked by spasmodic asthma, was crumbling. Medicine had failed to cure him. Drugs had ceased to help. Something needed to be done.

His only chance was to flee the “old grey country” of England in favor of a warm, dry climate … providing he lived long enough to move. Crowley and Jones recognized the failure of conventional avenues to cure their beloved Frater Iehi Aour, and journeyed down an alley they trusted more than the thoroughfares: magic. In an effort to prolong Bennett’s life enough for him to reach a healthier climate, Crowley and Jones turned to the Goetia .

The temple was thick with dittany of Crete burning in the censer in the south. An acacia altar, twice as tall as it was square, sat within the protective circle. Outside the circle, the Triangle of the Art awaited the appearance of the summoned spirit. With everything prepared, they conjured Buer, an infernal president who, according to the Goetia , “healeth all distempers in man.” It was a modest working, for Buer, although he commanded fifty legions of spirits, was but a president in rank: neither a king, duke, prince, prelate, nor marquis.

As they conjured, they noticed the clouds of incense dispersing unevenly, hanging in clumps in the air. In places, the smoke became almost opaque. As Fratres Perdurabo and Volo Noscere proceeded, the room cleared of incense except around the censer, where it accumulated thick and heavy in a distinct pillar of smoke. A shape began materializing in the smoke. With their apparent success, the magicians proceeded to the “Stronger and More Potent Conjuration” from the Goetia , which caused parts of the figure to grow vaguely distinct. They made out a helmet, part of a tunic, and solid footgear.

It was all wrong. It contradicted the Goetia ’s description of Buer. Crowley and Jones shot glances at each other, and decided against learning what they had inadvertently summoned. Before the materialization completed, they banished and closed the temple.

Foyers was just another vacation for Crowley, an opportunity to scale the rocks overlooking Loch Ness. He reposed on the north side of the Loch, across from the ruins of Urquhart Castle, one of Scotland’s largest castles until it was bombed in 1692 to prevent the Jacobites from using it. Conquering cliff after cliff, rock after rock, Crowley reached the pinnacle of an outcropping and looked down at the countryside. Precipitous rocks juxtaposed hills of heather. The earth sloped up gently from the Loch. A larch- and pine-covered hillock filled one spot; upon its mound he saw a house.

Named Boleskine, it was a huge one-story lodge, built in the late eighteenth century by the Honourable Archibald Fraser (1736-1815) and passed through the Fraser family ever since. The manor boasted a pillared entranceway and terrace, a large formal garden, lodge, stable, boat house, and sacred well. It overlooked the Fraser burial grounds, a seventeenth-century graveyard enclosed by a spear-tipped wrought-iron fence. A long driveway wound away from the house, through low-hanging trees, and toward the road that led to Foyers, 1.5 miles south, and Inverness, eighteen miles north. The house, he thought, was perfect for the Abramelin operation. The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage stipulated that one’s oratory have windows opening onto an uncovered terrace, plus a lodge to the north. The building met these requirements.

“I must have it,” he thought.

He rang the owner, Mary Rose Burton, and explained his interest. She told him Boleskine was not for sale. He insisted he must have it, and offered her £2,000—twice its market value. 45 She said it was a deal. By November, Boleskine was Crowley’s.

Boleskine, Crowley’s home on Loch Ness. (photo credit 3.4)

In the time between Boleskine’s discovery and sale, Crowley kept busy with magic and poetry. He eagerly discussed magic with Gerald Kelly, and one letter on the subject is particularly illuminating in light of his later philosophy of the True Will:

Conjure up the image of your father in your mind’s eye. When you have got him standing before you almost as solid as if you were there, say, ‘I will go to A.C. at Boleskine, Foyers, Iverness’ in the most determined voice. Let every incident of the day remind you of your will , and devote any spare moment to the imagination formula as well. In a very few days of this, interspersed with frequent letters home stating your will , will certainly have the desired effect. 46

On Halloween 1899, Kelly became Frater Eritis Similis Deo (“You will be like God”) on his introduction to the GD G. C. Jones sponsored Kelly, as he had Crowley. Kelly found Jones sincere and likable; however, unimpressed by its other members, Kelly never advanced beyond the grade of Neophyte.

In November, Mathers authorized Crowley to act as his London agent concerning publication and distribution of his Abramelin translation. Around this same time, AC also arranged to publish five hundred copies of his own An Appeal to the American Republic (1899). Reviews of this twelve-page booklet are not preserved, but the poem was later reprinted in The English Review . He also wrote an essay on the magical significance of numbers; though never published in his lifetime, this fragment represents his first paper on a magical subject.

A happy homeowner, Crowley plunged more than ever into the trappings of his Scottish surroundings. He took long walks over the moors, hunted red deer and grouse, and called himself Laird Boleskine. On the edges of his land, he hung signs reading “Beware of the Ichthyosaurus!” and “The Dinotheriums are out today!” 47 Taking the lead of his GD mentor, he also donned the red plaid kilt of the MacGregor tartan, and affected the name Aleister MacGregor.

With the perfect place in which to retire for the Abramelin operation, he was ready to advance through the portal from the First Order to the Second Order of the GD. He thus applied to the Second Order with all eagerness and sincerity. Their refusal stunned him. Crowley was being made an example for the order. It was nothing personal, as Farr liked Crowley and, several years later, would defend him in the New Age; but she deemed Crowley unfit. It was an example of Farr playing the part of Praemonstrix, “a role which she assumed with occasional outrageous officiousness.” 48

Some time between the ritual for Bennett’s health and Crowley’s rejection by the Second Order, Crowley received another in a series of plaintive letters from one of his lovers. Lilian Horniblow was the wife of Colonel Frank Herbert Horniblow of the Royal Engineers, who was stationed in India at this time. 49 The affair ended when Perdurabo devoted himself to the Abramelin operation and observed the spiritual and physical conditions of abstinence. She pleaded to see him again and invited him to her hotel. Although he had dismissed her previous requests, he agreed to this one because he had a plan.

He arrived at her room, confronted her coolly, and told her: “You are making a mess of your life by your selfishness. I will give you a chance to do an absolutely unfettered act. Give me £100. I won’t tell you whom it’s for, except that it’s not for myself. I have private reasons for not using my own money in this matter. If you give me this, it must be without hoping or expecting anything in return.” 50 Crowley’s private reasons are curious: Bennett needed £100 to leave England. Crowley refused to give the money himself not out of greed but because he feared the transaction would ruin their friendship. Although Crowley provided Bennett with free room and board, he did so in exchange for lessons in magic. Thus both parties retained their dignity.

One hundred pounds. His mistress pondered, and handed it over. Crowley took it and beat a hasty retreat from her life.

The Buddhist monasteries were Bennett’s destination. Magic was useless to him there, so on his departure he gave his GD notes to Crowley. 51 Then he was gone. On Bennett’s departure, AC wrote:

O Man of Sorrows: brother unto Grief!

O pale with suffering, and dumb hours of pain!

O worn with Thought! thy purpose springs again

The Soul of Resurrection: thou art chief

And lord of all thy mind: O patient thief

Of God’s own fire! What mysteries find fane

In the white shrine of thy white spirit’s reign,

Thou man of Sorrows: O, beyond belief! 52

Meanwhile, Crowley’s jilted mistress had more than a cold shoulder in mind when she handed over £100 for mysterious purposes. When all she received was a hurried thank-you, she protested. Word got around, and that January, Laird Boleskine invited her to stay at his new home. He offered to pay her expenses as compensation for the money in dispute. She accepted and made the journey.

No doubt precipitating this invitation, Horniblow had warned Crowley that he was about to find himself in what he, in his diary, referred to as “Great Trouble.” The nature of this trouble varies: one account has Horniblow complaining to the police about her loss of £100, and some of Yeats’s letters (quoted below) support this theory. Another connects this to Crowley’s relationship with Pollitt back at Cambridge. Supporting this homosexual scandal theory, he received two letters on January 15, 1900, warning that the police were watching him and his friends at 67 Chancery Lane because of something related to the “brother of a college chum.” 53 When refused entry into the GD’s Second Order, the reason was suspicion of “sex intemperance on Thomas Lake Harris lines in order to gain magical power—both sexes are here connoted.” 54 Indeed, both scandals may have come into play.

That night, Crowley continued on to Paris and visited Mathers. On Tuesday, January 16, Mathers initiated him into the grade of Adeptus Minor (5°=6°), the first grade of the GD’s Second Order. While the First Order was known as the Order of the Golden Dawn in the Outer, the Second Order was called the Rosea Rubea et Aurea Crucis (Ruby Rose and Cross of Gold).

Like all GD initiations, this one involved dramatic ritual. It drew heavily upon Rosicrucian symbolism and Mathers’s connections with the SRIA. The initiate was instructed by officers, then dressed in a black Robe of Mourning and draped with the Chain of Humility. Next, he was tied to the Cross of Suffering, and took the following tenfold oath:

(1) I, [the candidate’s motto is used here], a member of the body of Christ, do this day, on behalf of the Universe, spiritually bind myself, even as I am now bound physically unto the Cross of Suffering:

(2) That I will do the utmost to lead a pure an unselfish life.

(3) That I will keep secret all things connected with this Order; that I will maintain the Veil of strict secrecy between the First and Second Order.

(4) That I will uphold to the utmost the authority of the Chiefs of the Order.

(5) Furthermore that I will perform all practical work connected with this Order, in a place concealed; that I will keep secret this inner Rosicrucian Knowledge; that I will only perform any practical magic before the uninitiated which is of a simple and already well-known nature, and that I will show them no secret mode of working whatsoever.

(6) I further solemnly promise and swear that, with the Divine permission, I will from this day forward apply myself unto the Great Work, which is so to purify and exalt my spiritual Nature that with the Divine Aid I may at length attain to be more than human, and thus gradually raise and unite myself to my higher and divine Genius, and that in this event I will not abuse the Great Power entrusted unto me.

(7) I furthermore solemnly pledge myself never to work at any important Symbol or Talisman without first invocating the Highest Divine Names connected therewith; and especially not to debase my knowledge of Practical magic to purposes of Evil.

(8) I further promise always to display brotherly love and forbearance towards the members of the whole Order.

(9) I also undertake to work unassisted at the subjects prescribed for study in the various practical grades.

(10) Finally, if in my travels I should meet a stranger who professes to be a member of the Rosicrucian Order, I will examine him with care, before acknowledging him to be so. 55

The Robe of Mourning and Chain of Suffering were removed from the candidate, who next learned the history of the Rosicrucian Order: it began with Christian Rosenkreuz, a mythical German noble who was initiated into the Mysteries in Arabia in 1393. He traveled and studied the teachings of world religions until 1410, when he and four Masons whom he had initiated founded a temple of the Rosy Cross. After Rosenkreuz died he was buried in a vault within the temple undisturbed until, over a century later, a brother who had been repairing the temple discovered a secret door inscribed with the words POST CXX ANNOS PATEBO (I will be found after 120 years). The rediscovery of the vault occurred precisely 120 years after Rosenkreuz’s death.

The name Crowley chose as an Adeptus Minor was one he guarded closely all his life. He recorded this motto in only one notebook as Christeos Luciftias. In the Enochian angelic language, it means “let there be light.” Allan Bennett’s motto meant the same thing in Hebrew; the reference to his friend and mentor is clear. Crowley’s motto is also interesting as its surface resemblance to Western Christian terms contrasts and unites the names of Christ and Lucifer. 56 Its only appearance in print is as the “translator” of “Ambrosii Magi Hortus Rosarum,” a satirical Rosicrucian essay included in his Works .

The initiation marked a milestone for Crowley. Dissatisfied with the instructions of the First Order, he had followed advice to wait until he reached the Second Order before judging the system. The First Order, he had learned, served only to prepare the student; the Second Order taught the application of magic. Now he was ready for the real secrets. The initiation was also a victory for Mathers. While the order in London had refused to advance Crowley, Mathers overruled Farr’s decision. The war had begun.

While in Paris, Crowley asked Mathers for advice on the legal trouble brewing in London. Mathers examined Crowley’s astrological chart and, based on the date of the letters of warning, concluded there was real danger. However, his Saturn on the cusp of Capricorn mitigated things. “You are strong and the end of the matter is good,” Mathers counseled. “By all means, avoid London.” 57

Using the lunar pantacle from the Key of Solomon in order to avoid trouble, Crowley took his chances and briefly returned to London to check in with his associates. While Bennett, Jones, and Eckenstein believed his concerns were unfounded, GD member W. E. H. Humphrys warned Crowley that he was indeed wanted, and that the danger was greatest just before Easter.

Crowley left London and reached Boleskine safely on February 7. In his absence, Horniblow had left without warning or explanation. The reason lies in one of Yeats’s letters about the GD’s activities at this time:

We found out that his [Mathers’s] unspeakable mad person [Crowley] had a victim, a lady who was his mistress and from whom he extorted large sums of money. Two or three of our thaumaturgists … called her up astrally, and told her to leave him. Two days ago (and about two days after the evocation) she came to one of our members (she did not know he was a member) and told a tale of perfectly medieval iniquity—of positive torture, and agreed to go to Scotland Yard and there have her evidence taken down. Our thaumaturgist had never seen her, nor had she any link with us of any kind. 58

Nothing would ever come of this, although the gossip would haunt Crowley years later in the yellow press.

Crowley waited langorously in his tranquil new neighborhood for things to quiet down in London. On Saturday, February 24, he began recording his preparations for the Abramelin working, starting with his Oath of the Beginning:

I, Perdurabo, Frater Ordinis Rosae Rubeae et Aureae Crucis, a Lord of the Paths in the Portal of the Vault of the Adepts, a 5°=6° of the Order of the Golden Dawn; and an humble servant of the Christ of God; do this day spiritually bind myself anew:

By the Sword of Vengeance:

By the Powers of the Elements:

By the Cross of Suffering:

That I will devote myself to the Great Work: the obtaining of Communion with my own Higher and Divine Genius (called the Guardian Angel) by means of the prescribed course; and that I will use my Power so obtained unto the Redemption of the Universe.

So help me the Lord of the Universe and mine own Higher Soul! 59

With these words, he also took an Obligation of the Operation, which he adapted from his Adeptus Minor oath.

From the outset, circumstances seemed to oppose this working. Jones was the obvious choice for Crowley’s assistant, but he was unable to come to Boleskine. Therefore, Crowley summoned Bennett’s old roommate, Charles Rosher; he helped for a while but sneaked off early one morning and caught a steamer to Inverness, never to return. Rosher’s replacement was an old Cambridge friend, who also came and left suddenly. Finally, Boleskine’s teatotalling lodge-keeper went on a three-day drinking binge and tried to kill his wife and children. This and similar phenomenon convinced Crowley that the daily prayers and conjurations which constituted the Abramelin working were also attracting malevolent forces. 60

Florence Farr, troubled by her schism with Mathers, resigned as both Praemonstrix of the Isis-Urania temple and as his London representative. Mathers feared her resignation indicated Westcott’s attempt at a coup: on February 16 he sent her a letter claiming that Westcott

has never been at any time either in personal or in written communication with the Secret Chiefs of the Order, he having either himself forged or procured to be forged the professed correspondence between him and them, and my tongue having been tied all these years by a previous Oath of Secrecy to him. 61

The accusation was devastating. If Mathers was telling the truth, then she had been living a lie for years, initiating people under false pretenses.

To sort out her feelings, Farr returned to her childhood home of Bromley, where, after much contemplation and soul-searching, she decided to share the letter with six other members of the Second Order. On March 3, these seven formed an informal committee to quietly decide what they should do about Mathers’s accusations. The committee included Farr, Yeats, and Jones, as well as Mr. and Mrs. E. A. Hunter, M. W. Blackden, and P. W. Bullock.

On March 18, Bullock wrote Mathers on behalf of the committee, expressing shock over the letter’s implications and requesting proof of its accusations. Mathers shot an angry letter to Farr, refusing to recognize any committee formed “to consider my private letter to you … All these complications could have been avoided had you written me an open straightforward letter at the beginning of the year, saying you wished to retire from office .” 62

Two days later, Yeats contacted Westcott. The Rosicrucian Supreme Magus’s response was noncommittal:

Speaking legally , I find I cannot prove the details of the origin of the knowledge and history of the G.D., so I should not be just nor wise to bias your opinion of them.

Mr. M. may insinuate and claim the authorship because I cannot disprove him. How can I say anything now, because if I accepted this new story, then Mrs. Woodman would rightly charge me with slandering her dead husband’s reputation, for he was answerable for the original history; and if I say M.’s new story is wrong I shall be open to violent attack by him and I shall have to suffer his persecution.

I must allow you to judge us both to the best of your judgement, and to decide on your responsibility. 63

On March 23, Mathers sent poison pen letters to Farr and Bullock, again expressing umbrage at having his letter shown to others and refusing to recognize their committee. Calling on the vows of obedience to him which all members signed in 1896, he forbade the committee to meet and ordered them to abandon the inquiry. He also dismissed Farr as his representative.

The next day, the committee met to decide on a plan of action, and Bullock wrote apologetically to Mathers, stating that his letter forbidding meetings reached him after the committee had already met. Mathers wrote back to Bullock on April 2 and threatened the committee. “And for the first time since I have been connected with the Order,” he wrote, “I shall formulate my request to Highest Chiefs for the Punitive Current to be prepared, to be directed against those who rebel.” 64

The situation in London had continued for over a month when Crowley made his first contact with the lodge since his initiation by Mathers. From Boleskine, he wrote Maud Cracknell, assistant secretary of the Second Order, whom he bitterly called “an ancient Sapphic crack, unlikely to be filled.” 65 As an Adeptus Minor in the GD, he requested the instructional papers to which he was entitled, but Cracknell told him he needed to deal directly with Mrs. Hunter, his superior in the order. Crowley’s letter to her couldn’t have been worse timed. Hunter was on the investigative committee and unkindly disposed to Mathers. On March 25, Mrs. Hunter sent Crowley a reply wherein she refused to recognize his initiation into the Second Order. “The Second Order is apparently mad,” he mused. In Crowley’s mind, Mathers was

unquestionably a Magician of extraordinary attainment. He was a scholar and a gentleman.… As far as I was concerned, Mathers was my only link with the Secret Chiefs to whom I was pledged. I wrote to him offering to place myself and my fortune unreservedly at his disposal; if that meant giving up the Abra-Melin Operation for the present, all right. 66

A week later, Mathers accepted the offer. In his diary, Crowley noted,

D.D.C.F. accepts my services, therefore do I again postpone the Operation of Abramelin the Mage, having by God’s Grace formulated even in this a new link with the Higher, and gained a new weapon against the Great princes of the Evil of the World. Amen. 67

On Tuesday, April 3, Crowley stopped in London to ask his oldest friends in the order their opinion of the rebellion. Baker told Crowley he was sick of all the politicking in the order, while Jones insisted that, without Mathers, there was no GD. Elaine Simpson also took Mathers’s side. Crowley also consulted Kelly and Humphrys, but their reactions are unrecorded.

That Saturday, Crowley appeared at the Second Order’s meeting room at 36 Blythe Road. His plan was to reconnoiter the order’s property for Mathers, but he found the vault locked and Miss Cracknell on duty. “I insist I be allowed inside,” he pressed her.

“The Vault is closed by order of the committee, and no one can go in without its consent,” she told the intruder coolly.

“Have you a key?”

“I’m a new member and don’t have a private key,” she lied.

“Can you go in yourself?”

“No,” she lied again. “Perhaps you’d better go to Mrs. Emery, or Mr. Hunter or Mr. Blackden.”

“On the contrary. It is they who should come to me.” At that, he dramatically stormed out of the room. Satisfied with his observation of the situation in London, he proceeded to France.

Crowley returned to 28 rue St. Vincent on Monday, April 9, and proposed a strategy to the Matherses: Crowley should return to London and summon the members of the Second Order individually to headquarters. There, they would encounter a masked man (Crowley) and his scribe. They would answer whether they believed in the truth of the teachings of the Second Order and were willing to stop the revolt; then they would sign a vow of obligation to the GD. Any refusal would mean expulsion.

Mathers accepted the plan. On April 11 he penned letters of authorization for Crowley. The next day, Crowley entered the following oath into his diary:

I, Perdurabo, as the Temporary Envoy Plenipotentiary of Deo Duce Comite Ferro & thus the Third from the Secret Chiefs of the Order of the Rose of Ruby and the Cross of Gold, do deliberately invoke all laws, all powers Divine, demanding that I, even I, be chosen to do such a work as he has done, at all costs to myself. And I record this holy aspiration in the Presence of the Divine Light, that it may stand as my witness. 68

Crowley left Paris at 11:50 a.m. on April 13. For protection, Mathers gave him a Rose Cross, the Rosicrucian talisman. He warned Crowley to expect magical attack, and know that sure signs were mysterious fires or fires refusing to burn. It was the best he could do to prepare Crowley for the fight ahead.

Back in London, Crowley’s first tactic was to contact GD members loyal to Mathers. He hired a cab to take him to two of these members, Mrs. Simpson and Dr. Berridge. During the ride, the paraffin lights on the carriage caught fire and the cab could go no further. Most mysterious, Crowley thought, in light of Mathers’s warning about fires. He hailed another cab, and as he rode along the horse bolted inexplicably.

When he finally arrived at Mrs. Simpson’s, Crowley noted the refusal of her hearth fire to remain lit, while his rubber raincoat, nowhere near the fire, spontaneously combusted. Mathers appeared to be correct about the fires: when they should have burned, they did not; when they were burning, they behaved mysteriously; when they should not be, they appeared. Crowley concluded he was under magical attack.

Taking out the Rose Cross, Crowley clenched the protective talisman given to him by Mathers and noticed something unusual about it. Its color was bleaching out, fading. In one day’s time, the talisman was nearly white.

During this time as Mathers’s plenipotentiary, Crowley also had his one and only contact with Supreme Magus William Wynn Westcott:

I only saw the old boy once in my life, and then merely on an errand from Mathers to tell him he had incurred a traitor’s doom. And I only wrote to him once, and that to demand that he should deposit the famous Cypher Manuscripts with the British Museum as their secrecy was being used for purposes of fraud. 69

Westcott was less receptive to Crowley’s communications than he was to Yeats’s.

Thirty-six Blythe Road was the rebel base. As the Second Order’s London headquarters, it was the source of the insurrection’s power. Without it, they would be dead in the water.

On Monday, April 16, Crowley met C. E. Wilkinson, landlord of the room, and convinced him that he had authority to enter and occupy the premises. The next day, he returned with Elaine Simpson to wrest headquarters from the dissidents. They found Cracknell in the room, repeating her statement that the rooms had been closed by Farr’s order. As Mathers’s plenipotentiary, Crowley gleefully expelled the Sapphic Crack from the order. She rushed off and sent a telegram to E. A. Hunter: “Come at once to Blythe Road, something awful has happened.”

When Hunter arrived, he was shocked to encounter resistance in entering the room. Then he found Crowley in the supposedly locked premises, having apparently forced open the doors and changed the locks. Crowley proudly declared, “We have taken possession of headquarters by the authority of MacGregor Mathers.” He handed over his letters of authority.

Hunter looked the papers over. “The authority of that gentleman has been suspended by a practically unanimous vote by the members of the society,” he replied dryly.

Undaunted, Crowley turned his attack to Cracknell, who had entered the room with Hunter. Jabbing a finger in her direction, he continued. “That woman must leave the room. She has been suspended from membership.”

Hunter shook his head. “I will not allow it. Not without her consent.”

Meanwhile, Farr appeared with a constable. Unfortunately, the authorities were powerless to help her. The landlord was not present to verify ownership of the premises, and Farr had not put into writing her orders for the rooms to be closed. Crowley was technically in possession of the rooms.

Victorious, AC proceeded according to plan. To cancel the proposed meeting of the renegade Second Order on April 21 and to summon all members for their test of allegiance, he sent the following telegram:

You are cited to appear at Headquarters at 11:45 am on the 20th inst.

Should you be unable to attend, an appointment at the earliest possible moment must be made by telegraphing to ‘MacGregor’ at Headquarters. There will be no meeting on the 21st inst.

By the order of Deo Duce Comite Ferro,

Chief of the S O

O 70

70

Two days later, on April 19, Yeats and Hunter found Wilkinson, the landlord. Since members came and went regularly, he explained, he assumed Crowley was as welcome as any other. However, he agreed that Farr, who paid the bills, could do whatever she wanted with the rooms. They thereupon showed him a letter from Farr, authorizing them to change her locks.

At 11:30 that same morning, Crowley’s figure cut a spectacle through the shop below. He appeared in Highland dress with a plaid over his head and shoulders, a huge gold cross around his neck, and a dagger at his waist. According to plan, he wore a black mask over his face to conceal his identity. 71 Crowley marched past the shop clerk, who notified Wilkinson. The landlord—having passed word along to Yeats, Hunter, and the constable—stopped Crowley in the back hall and forbade him from entering the premises. When the constable arrived, he advised Crowley to get a lawyer.

Yeats and Hunter spent the rest of the day refusing as “name unknown” the flood of telegrams which arrived for “MacGregor.” This was interrupted at 1 o’clock by the arrival of a burly fellow who had been wandering the London streets for two hours trying to find 36 Blythe Road. Crowley had hired him outside Alhambra, a Leicester Square pub, for thirteen shillings four pence. The man had no idea why he was wanted there: he thought some sort of entertainment would be provided.

Later that day, the committee met and suspended Mathers, Berridge, and Mrs. and Miss Simpson from the Second Order. They further moved “no person shall be deemed to belong to the London branch who has not been initiated by that body in London.” It was a smack in Crowley’s face. The Mathers loyalists were unamused by their suspension. On Friday, April 20, Dr. Berridge (c. 1843–1923) replied to the committee upon learning of his expulsion:

I am in receipt of your note of yesterday in which you convey to me the decision of the self-appointed and unauthorised committee of your new Archaeological Association.

I have read it carefully but am at present unable to decide where impudence or imbecility is its predominant characteristic.

As I have never been a member of your new Society I cannot be suspended from such non-existent membership. 72

The next day, the committee reached a decision about Mathers: if his accusations of forgery were true, then he was guilty of fraud. If he was lying, then he was guilty of slander against a brother of the order. In either case, Mathers’s word was worthless.

Even at this point the battle raged. Crowley summonsed Farr to appear before the police magistrate of the West London Police Court on April 27 on charges of “unlawfully and without just cause detaining certain papers and other articles, the property of the Complainant.” 73 He wanted either the items returned or £15 remuneration. Appealing to friends in high places, the Second Order rebels hired as their representative Charles Russell, son of the Lord Chief Justice. Yeats feared his name would be dragged into the case and, awaiting the court hearing, wrote:

The case comes on next Saturday, and for a week I have been worried to death with meetings, law and watching to prevent a sudden attack on the rooms. For three nights I did not get more than 4½ hours sleep any night. The trouble is that my Kabbalists are hopelessly unbusinesslike and thus minutes and the like are in complete confusion. 74

To their advantage, however, they learned Crowley had been blacklisted by the Trades’ Protection Association for a bad debt; so they called in a trade union representative to testify in their defense.

Cracknell sent a letter to Crowley’s counsel in an effort to clear matters up. She explained that Farr was president and Hunter treasurer of the order; Mathers acted only as honorary head, but had never been in 36 Blythe Road, let alone contributed financially to its upkeep. She also described how Crowley broke into the premises, adding, “certain things of pecuniary value to the society were found to be missing.” 75

The day of the trial, Yeats—having just been elected the GD’s new leader—sat at home like an expectant mother, awaiting the news. He wrote to Lady Gregory:

I do not think I shall have any more bother for we have got things into shape and got a proper executive now and even if we lose the case it will not cause any confusion though it will give one Crowley, a person of unspeakable life, the means to carry on a mystical society which will give him control of the conscience of many. 76

He finished and sealed the letter but, before he could mail it, the news arrived. They had won. Crowley’s solicitor, concluding they had no case, feared the GD would claim their losses exceeded £15, thus taking the case to a higher court. To avoid this complication, they withdrew charges for a £5 penalty.

Easter had passed, and it was thus too late for Crowley to resume the Abramelin operation. He returned to Boleskine for a few somber days, then returned to Mathers in Paris. Berridge, he learned, had joined Westcott to set up a new branch of Isis-Urania under Mathers’s direction. 77 Evidently the controversy did not prevent Mathers and Westcott from collaborating.

During his visit, Crowley convinced Mathers to unleash the punitive current against the rebels. He thus spent a Sunday afternoon watching Mathers baptize dried peas in the names of the rebels and rattling them around inside a sieve. Crowley, unimpressed, recorded, “nobody seemed a penny the worse.” 78

Thus ended the revolt in the GD, with Mathers believing he had been the victim of a conspiracy, and Yeats regretting the loss of a friend. Shortly after the break, Yeats recalled Mathers respectfully: “MacGregor apart from certain definite ill doings and absurdities … has behaved with dignity and even courtesy.” 79 Years later, he recalled his old friend in a poem:

I call MacGregor Mathers from his grave,

For in my first hard spring-time we were friends,

Although of late estranged.

I thought him half a lunatic, half knave,

And told him so, but friendship never ends … 80

In 1925 he fondly dedicated his book A Vision to Moïna. Although they parted bitterly, the Matherses’ influence upon him never faded.