Kegan Paul disappointed Crowley with slow sales and price reductions on his overstocked titles. Since 1902, only ten copies of Tannhäuser had sold, five of Carmen Sæculare , seven of Soul of Osiris , and two of Jephthah. Appeal to the American Republic, The Mother’s Tragedy, Tale of Archais , and Songs of the Spirit had not sold at all. In May 1904, Crowley closed his account with the publisher 1 and called on Charles Watts of London to do his printing. To combat what he considered mismanagement of his stock of books, Crowley decided to distribute his works himself. He named his publishing house the Society for the Propagation of Religious Truth (SPRT), a parody of the Church of England’s venerable Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Much speculation has surrounded Crowley’s decision to move his book publishing activities from London to Foyers, with some erroneously suggesting he was avoiding criminal charges for strangling a woman. As he rebutted,

My dealings with Kegan Paul had nothing at all to do with the strangling of any woman. The unsold copies of my books were taken over by the Society for the Propagation of Religious Truth, because Kegan Paul were making no efforts to sell them.… So please loosen the rope round the poor lady’s neck. 2

A glut of new releases appeared in privately published editions as he prepared the transition to SPRT.

Alice: An Adultery , commemorating his Pacific affair in one hundred copies on China paper, met with cold press reactions. The Star and the Garter appeared in a companion edition of fifty on handmade paper and two on Roman vellum; although Crowley thought the book contained “some of my best lyrics,” 3 reviewers deemed it unintelligible. The God Eater followed the camel hair wraps format of these previous titles; it was a short play (thirty-two pages) that Crowley would later call “singularly unsatisfactory.” 4

Business stopped at Boleskine on July 28 when Dr. Percival Bott 5 (1877–1953) delivered the Crowleys’ healthy daughter, whom the proud father named Nuit Ma Ahathoor Hecate Sappho Jezebel Lilith. For days afterward, Crowley celebrated with Bott, Back, Kelly, Rose, Duncombe-Jewell, and Aunt Annie. Rose wanted something to read while recuperating, but found her husband’s collection of literature, philosophy, and mysticism far too cerebral. She wanted a simple romance. Having none at his disposal, Crowley decided to write his own brand of romance novel for the entertainment of his convalescing wife and their house guests. Thus, house party activities daily involved a reading of the chapter Crowley had written that day for “The Nameless Novel.”

“Good, by Jesus!” cried the Countess, as, with her fat arse poised warily over the ascetic face of the Archbishop, she lolloped a great gob of greasy spend from the throat of her bulging cunt into the gaping mouth of the half-choked ecclesiastic. 6

So begins the chronicle of a sexually demented archbishop, a novel purposely vulgar and shocking to parody what Crowley considered the only type of book Rose would enjoy. Throughout the writing of this piece, Crowley kept Farmer and Henley’s Slang and its Analogues nearby. The results so entertained his guests that Kelly and Back helped assemble Crowley’s early attempts at vulgar verse and puerile parody into a package titled Snowdrops from a Curate’s Garden . It included such gems as “To pe or not to pe,” “All the world’s a brothel,” “Bugger me gently, Bertie!” and “Girls together.” Of course, there wasn’t an English press that would touch it.

After the household cleared, the Crowleys adjusted to their roles as parents. AC put aside magic to be a husband and father. In a letter to her brother, Rose captured the mood of these times:

All goes well here. The kid—Nuit Ma Ahathoor Hecate Sappho Jezebel Lilith—to be called by the last name—flourishes. She’s a good little maid tho’ she does squawk occasionally which drives Aleister out rabbit shooting. We’ve such a stock to consume in the house! 7

Despite the time that fatherhood took from his magic, Crowley the poet continued to thrive: The Sword of Song, called by Christians The Book of the Beast , dedicated to Allan Bennett, appeared to the astonishment of the press. Stephensen (1930) correctly called it a complex work, and it is the most important of his early books. The edition of one hundred copies, at ten shillings, was one of his most expensive books to date, but, at 194 pages, it was also among his longest. Its navy blue cover, printed in gold, bore mysterious emblems: a three-by-three set of squares depicting the number 666 thrice, and the author’s name rendered in Hebrew such that its numerical value added up to this same number. Within is the autobiographical passage:

Yet by-and-by I hope to weave

A song of Anti-Christmas Eve

And First- and Second-Beast-er Day.

There’s one who loves me dearly (vrai!)

Who yet believes me sprung from Tophet,

Either the Beast or the False Prophet;

And by all sorts of monkey tricks

Adds up my name to Six Six Six …

Ho! I adopt the number. Look

At the quaint wrapper of this book!

I will deserve it if I can:

It is the number of a Man. 8

In this poem, the one who loves him dearly is his mother; Tophet is the abyss of hell, and the last line refers to Revelation 13:18: “Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast; for it is the number of a man; and his number is 666.” This poem is significant because it corrects the common assertion that Crowley identified himself with the Great Beast when he assumed the mantle of prophet of the New Aeon of Horus: this poem was written before The Book of the Law . Similarly, Crowley registered himself in Egypt as “Chioa Khan,” Master Beast, before writing his Holy Book. Thus, his identification with the Great Beast 666 predated The Book of the Law , and most certainly originated with Crowley’s mother, who so often referred to him as such. In this and various other ways, The Sword of Song documents Crowley’s intellectual and philosophical developments that adumbrate The Book of the Law .

Aside from poetry, The Sword of Song also contained the essays “Berashith,” “Science and Buddhism,” and “Ambrosii Magi Hortus Rosarum,” a work that would come back to haunt him in later years. The entire package is an odd and entertaining mix of mystic poetry and essays on Buddhist thought. Its notes and contents are snide, cynical, and often amusing. While the Literary Guide praised the book as “a masterpiece of learning and satire” and its author as “one of the most brilliant of contemporary writers,” 9 reviewers generally reacted with perplexity. Following up on his review of Soul of Osiris , G. K. Chesterton titled his reactions to AC’s latest work “Mr. Crowley and the Creeds,” calling him a good poet but expressing reservations about his Buddhist faith and obvious hatred of Christianity. 10 Crowley reacted defensively, and issued a pamphlet titled “A Child of Ephraim.” It merely signaled the beginning of Crowley’s crusade against Chesterton.

In October, Crowley traveled to the resort town of Saint Moritz, Switzerland, for a holiday of skating and skiing. En route, the bard stopped in Paris around the 28th to arrange with Philippe Renouard the publication of Snowdrops from a Curate’s Garden for his friends. The edition of one hundred copies was bound in green wrappers, bearing the false imprint place of “Cosmopoli” (taken from the homosexual novel Teleny , attributed to Oscar Wilde and printed by Smithers). Equally false was the imprint date of 1881 (the publication year of the homosexual novel Sins of the Cities of the Plain ). 11 Rose, wishing a vacation from mothering, left Lilith with her parents and their nurse, and joined Aleister in November. They stayed at the fashionable Kulm Hotel. The other guests were stunned and amused by AC’s ermine-lapelled velvet coat, silk knee-breeches, and enormous meerschaum pipe. He likewise sneered at the bourgeois patrons. They soon learned that he was not only an accomplished mountaineer, scholar, and poet, but the finest skater there.

Another guest at the hotel was author Clifford Bax (1886-1962), then just eighteen years old. He had come with his two cousins to regain his health, and spent his spare time reading A History of the Rosicrucians . 12 The book prompted a discussion when he and Crowley met. “What do you know of the Great Science?” AC asked eagerly. “Or of Cornelius Agrippa? Perhaps you would find this helpful.” He handed the young man a vellum book. Looking it over, he discovered it was by Crowley. “It is a treatise on ceremonial magic.”

“Thank you,” Bax replied, looking around to see if anyone was watching.

Crowley dismissed his concern. “What do you think the morons in this hotel would make of your interest in the Rosicrucians?”

Before he knew what was going on, Bax found Crowley offering to instruct him in magic. “Most good of you,” Bax replied sheepishly, “but … maybe I’m not ready. I think I should read some more.”

“Nonsense! Reading is for children; men must do. Experiment! Seize the gift the gods offer. If you reject me, you will be indistinguishable from the idiots around us. If you accept my offer, you can help me found a new world religion.” Suddenly, he shifted gears and asked, “What is the date?”

“January 25.” Bloody Sunday, the massacre at St. Petersburg, had just occurred three days before.

“And the year, according to the Christian calendar?”

“1905.”

Crowley nodded. “Exactly. And in a hundred years, the world will be sitting in the dawn of a New Aeon.” 13

When the frost yielded, the Crowleys returned to the British Isles. AC journeyed to London to tend to publishing business. Returning to Strathpeffer to fetch his wife, who was staying with her parents, he found Rose ill. She was also evasive about discussing her condition. Crowley pressed, and Rose finally explained: since Lilith was born, her periods had been irregular and she feared she was again pregnant. Her parents’ nurse, to whom she confided, gave her ergot to induce an abortion. When the prescription failed, a double dose followed. Then she became ill.

Crowley’s head swam with powerful emotions. He was furious that Rose should attempt to snuff a life and jeopardize her health through abortion. He was also suspicious of just what substance the nurse had been giving his wife to make her so ill. Bundling Rose and Lilith, he took his family to the Imperial Hotel and wired Bott and Back, the only physicians he trusted, to meet him at London’s Savoy Hotel. Then he wired Gerald to get Roses’s medicine under the pretense of sending it to her in London, and have a chemist analyze it. Then the Crowleys began a return trip to London. Bott and Back heard the case and, in the end, agreed on the diagnosis: Rose was not pregnant, but she was suffering from the worst case of ergot poisoning they had ever seen.

Having heard enough, he returned to Boleskine. Here he wrote “Rosa Inferni,” a sequel to “Rosa Mundi,” thus continuing what would become a cycle of four poems chronicling the phases of his relationship with Rose. He also wrapped up work on the manuscripts of Orpheus and Gargoyles .

Crowley’s works appeared under the SPRT imprint faster than they’d come out before, with ten new works and various reissues appearing at this time.

The first of these was The Argonauts (1904), influenced by Crowley’s exposure to Hinduism. Reviewers generally liked the writing in this five-act verse play, but considered it uneven. This comment underscores the disadvantage to Crowley’s method of publication: unable to criticize his own works, he published books as he wrote them without an editor to identify their weaknesses. Furthermore, the limited print runs—generally one hundred to two hundred copies—left little opportunity for his name to become known.

The Book of the Goetia of Solomon the King (1904) was Mathers’s translation of the Key of Solomon , which Crowley had acquired during his raid of the GD’s Second Order headquarters in April 1900. Although Crowley was responsible for emendations, introduction, and notes, Mathers is credited only on the title page as “A Dead Hand.”

One hundred copies of his next work, Why Jesus Wept: A Study of Society (1904), sold to subscribers at two guineas through a tacky advertisement:

WHY JESUS WEPT

by

Aleister Crowley

Who has now ceased to weep

With the original Dedication;

With the advertisement which has brought Peace and Joy to so many a sad heart!!

With the slip containing the solution of the difficulty on pages 75–76!!!

With the improper joke on page 38!!!!

With the beetle-crushing retort to Mr. G.K. Chesterton’s aborted attack upon the Sword of Song!!!!!

With the specially contributed Appeal from the Poet’s Mamma!!!!!!

Look slippy, boys! Christ may come at any moment. He won’t like it if you haven’t read the book about His melt.

… I say: Buy! Buy Now! Quick! Quick!

My Unborn Child screams “Buy!”

The poetic play, its title from John 11:35, is a religious satire explaining why Jesus wept. It reprints a letter from Crowley’s mother, wherein she begs her strayed son to give up his evil ways. Crowley signed the dedication in Hebrew such that the name “Aleister E. Crowley” added up to 666, as it did on the cover of The Sword of Song; he dedicated the book to Jesus, Lady Scott (a portion of whose anatomy he compared to a piece of wet chamois), his Buddhist friends, his unborn child, and, particularly, G. K. Chesterton, to whom Crowley wrote, “Alone among the puerile apologists of your detestable religion you hold a reasonably mystic head above the tides of criticism.” Inserted into the book was an eight-page pamphlet reprinting Chesterton’s “Mr. Crowley and the Creeds,” along with Crowley’s rebuttals: “The Creed of Mr. Chesterton” and “A Child of Ephraim.” Chesterton appears in the book, along with “The Marquis of Glenstrae” and a Horny-Handed Plymouth Brother.

In Residence: The Don’s Guide to Cambridge (1904), dedicated to Ivor Back, reprinted Crowley’s undergraduate verse; The Granta , Cambridge University’s undergraduate magazine, replied:

Oh, Crowley, name for future fame!

(Do you pronounce it Croully?)

Whate’er the worth of this your mirth

It reads a trifle foully.

Cast before swine these pearls of thine,

O, great Aleister Crolley

“Granta” to-day, not strange to say,

Repudiates them wholly. 14

Several of these books included the SPRT catalog and an entry form for a contest: Crowley was offering £100 as grand prize for the best essay written on his works. He designed the scheme to promote sales of his “Collected Works” (see below) and the overstock of his previous works. The flier is every bit as silly as that for Why Jesus Wept:

THE CHANCE OF THE YEAR!

THE CHANCE OF THE CENTURY!!

THE CHANCE OF THE GEOLOGIC PERIOD!!!

A CAREER FOR AN ESSAY 15

By this time, SPRT’s booklist numbered nineteen titles, with volume one of the collected works offered at cost to any competitor, who was free to write either a hostile or appreciative essay. His first editions were also for sale, priced from twenty-one shillings (Aceldama, Jezebel, Alice, Goetia , and Why Jesus Wept) to one shilling (Appeal to the American Republic, The Star and the Garter) .

The Works of Aleister Crowley , volume 1, covered his books from Aceldama to Tannhäuser (omitting the anonymous publication White Stains ), edited and footnoted by Ivor Back. The uneven quality of his writing notwithstanding, Crowley’s accomplishment, at age twenty-nine, of a three-volume collection of his published works remains remarkable.

Five hundred copies of Oracles: The Autobiography of an Art (1905) were also available, with the SPRT catalog bound in at the end. This book was a collection of poetic odds and ends, including his early work and selections from the unpublished Green Alps . The author described this book as “a hodgepodge of dejecta membra … [containing] beastlinesses too foul to cumber up my manuscript case any more.” 16

Crowley, ever searching for new ways to make his works rare and desirable, issued the two-volume Orpheus: A Lyrical Legend (1905) in five editions distinguished by the covers’ elemental colors (either white, yellow, red, blue, or olive green). A one-volume edition was also available on India paper. Of this work, Crowley later wrote, “They had never satisfied me.” 17

Rosa Mundi: A Poem (1905), published by Philippe Renouard, featured the fifteen-page title piece and a lithograph of one of the sketches Rodin had given him. Gargoyles: Being Strangely Wrought Images of Life and Death (1906) marked what AC considered a new phase of his work. Finally, in addition to publishing new works, Crowley reissued some of his older books in inexpensive editions, including The Star and the Garter, Songs of the Spirit , and Alice: An Adultery .

Although the effort would not make Crowley famous, this publishing and publicity spree would soon mean more to Crowley than he ever dreamed.

Jacot-Guillarmod arrived at Boleskine on April 27 and presented the lord of the manor with a copy of his book about their climb on K2, Six Mois dans l’Himalaya . 18 Crowley recalled how Guillarmod spent his hours on the glacier keeping a journal—it was probably the only thing that kept him from snapping like the others—and gladly accepted the gift. He reciprocated with a copy of Snowdrops from a Curate’s Garden .

During his visit, Guillarmod and Crowley discussed their respective adventures. When Guillarmod began to boast of his big game hunting, it piqued Crowley’s interest. “Have you ever seen a haggis?” he asked.

“Haggis? What’s that?” the Swiss asked.

Haggis was a Highland dish of minced sheep’s heart, liver, and kidneys boiled with oatmeal in the animal’s stomach. Drawing a dramatic breath, Crowley explained: “I am one of the only people who would dare answer that question. A haggis is a wild rogue ram.” Guillarmod knew of Burma’s wild buffaloes, and of elephants that were thrown out of their herds. Although he had never heard of a haggis, he equated it with these creatures. Crowley continued, “Just as rogue elephants are taboo, so is the haggis sacred in Scotland. They are rare, and, when found, must only be touched by the chief of the clan. They are also very dangerous.”

Guillarmod nodded gravely, suitably impressed. It gave Crowley a wonderful idea.

Two days later, Crowley and Guillarmod rested in the billiard room after breakfast. Their idyll was interrupted when Crowley’s servant, Hugh Gillies, burst breathlessly into the room, panic and urgency in his eyes. “My lord,” he blurted out, “there is a haggis on the hill.”

Guillarmod’s gaze shot from Crowley to the servant and back again. AC, doing his best to keep a straight face, nodded in acknowledgment. “Good man,” he muttered as he walked over to his gun case. “The best servant I’ve had.” He grabbed his .577 Double Express and handed Guillarmod a 10–bore Paradox with steel-core bullets. “That gun,” he told Guillarmod, “will bring down an elephant with a shot. You may need it. Now fall to. We haven’t a moment to lose.”

Crowley led Gillies, Guillarmod and Rose on a low-crouching, tiptoed course through icy rain that chilled them by the time they reached the artificial trout lake on his estate. Playing his part to the hilt, Crowley insisted, “We must wade through the lake to throw the haggis off our scent.” So, with guns held high overhead, they marched through the neck-high water. Emerging on the other side, they climbed the hill on all fours. Stealthy and cautious, they finally reached the hilltop ninety minutes after leaving the house. Crowley looked over to the servant. “Where is it?”

Gillies pointed a trembling finger through the mist. “Th-there.”

By this time, Guillarmod was so tightly wound that he advanced and fired at the beast in the mist. As the explosion of gunfire echoed through the hills, Crowley grabbed Guillarmod’s arm to restrain him. “If you value your life, stay where you are.” Lord Boleskine stepped into the gray haze. There, he found the ram he had purchased in town from Farmer McNab and tethered on the hill. Both bullets from the rifle had struck and expanded, completely blowing away the ram’s rear section. Crowley arranged to have the ram cooked and served for dinner the next evening. Guillarmod, none the wiser, had the animal’s head mounted on a plaque as a trophy. 19

As great an adventure as the haggis was, Guillarmod did not come to Boleskine to hunt rogue rams. He had come to discuss mountains. Six Mois dans l’Himalaya chronicled their attempt on K2, and he again desired that type of experience. He suggested to Crowley that they climb Kangchenjunga, the third highest mountain in the world.

Located twelve miles south of the main Himalayan chain, it was only forty-five miles north of Darjeeling, eighty miles east of Mount Everest. Its name literally meant “Five Peaks” for its pentad of summits ranging in height from 25,925 to 28,169 feet. These pinnacles were buttressed by huge ridges with several lesser though nevertheless spectacular peaks of their own; running east-west and north-south, they formed a giant X around the range. At 28,169 feet, Kangchenjunga was less than one hundred feet smaller than K2.

Climbers considered it the most treacherous mountain in the world. Receiving more precipitation than virtually any other mountain, hundreds of feet of snow and ice plastered its face and slowly plowed down the mountain in the form of glaciers, and its millions of tons of debris could easily tumble down as an avalanche. Its history testified to its inhospitability: in January 1849—when mountaineering was still in its infancy—Antarctic explorer Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817–1911) attempted Kangchenjunga, but snow turned him back. Returning three months later, difficult conditions cut his climb short. Three years later, in 1852, an earthquake brought thousands of square yards of debris down the mountain, preempting Captain J. L. Sherwill’s attempt. 20 W. W. Graham claimed to have circumnavigated the mountain in 1882 and to have climbed two of its lesser peaks in October 1883, but the account was controversial. Douglas Freshfield’s 1899 tour around the base of Kangchenjunga was cut short when a storm dumped twenty-seven inches of rain on Darjeeling in twenty-eight hours. In 1905, Kangchenjunga remained unclimbed. 21

The challenge appealed to Crowley. Disappointed by his abortive attempt on K2, he saw an opportunity to get it right. He insisted on leading the expedition, and he and Guillarmod both put five thousand francs into expenses. Crowley, realizing what little time they had if they wished to attempt the mountain that summer, devised a plan: Guillarmod would go to London and round up provisions while Crowley proceeded to Darjeeling to arrange transport, hire porters, and coordinate details with the local government.

When Crowley set off for London on May 6 to get his affairs in order, he was prepared to die. He left written instructions for his body to be embalmed, dressed in magical garb, and sealed in a vault on ground chosen and consecrated by his GD mentor, George Cecil Jones. In London, he sought Eckenstein, who considered the adventure foolhardy and declined to participate. Undaunted, Crowley gathered provisions and proceeded to Darjeeling. On May 12, Crowley sailed for India, where a month earlier a severe earthquake had killed over 19,000 people in its northern territory. He arrived in Bombay on June 9 and headed for Darjeeling the same day. From there he could have seen Kangchenjunga—and even the Himalayas—if not for the rain: it never stopped, and left everything damp and musty. Moving into the Drum Druid Hotel, he concluded he simply didn’t like Darjeeling.

While in India, Crowley kept up on business by mail. His contest for the best essay on the works of Aleister Crowley had drawn a contestant in the form of J. F. C. Fuller (1876–1966), a young army captain stationed at Lucknow. He had ordered a copy of Why Jesus Wept based on a review in The Literary Guide; the book impressed him and, finding the contest entry form, he decided to try his luck. Since he had none of the poet’s other works, Crowley sent along copies of everything. This included volume two of the Works of Aleister Crowley , which was still in press.

To prepare for the expedition, Crowley sent four tons of food to be taken as close as possible to the Yalung Glacier, where they would begin their ascent; this was conveyed by 130 porters provided by the Indian government. On the last day of July—having weathered a monsoon and mechanical difficulties—Jacot-Guillarmod arrived with two other Swiss climbers. 22 Crowley and a servant met them at the train station to help bring their bags to the hotel, where the manager had reserved for them his best rooms.

The team that Jacot-Guillarmod had assembled was solid. Charles Adolphe Reymond (1875–1914) of Fontaine, Val de Ruz, was a Swiss Army officer with Alpine experience, quiet and dour. He called himself a Lebenskünstler , or connoisseur of the art of living. His small pension afforded him a pleasant and simple lifestyle; for instance, he once spent an entire winter at Sainte-Croix, Switzerland, skiing and lazing in the sun. He was a natural and skilled climber, having worked with a guide primarily in the Valais and Mont Blanc chains. Until being enlisted for this climb, he worked as an editor at the Swiss telegraphic agency in Geneva. 23 Reymond quipped that the primary purpose of the expedition was to have a good time; beating the world altitude record was secondary. 24 AC liked him: he had good sense and seemed stable.

Charles Adolphe Reymond (1875–1914) of the Kangchenjunga expedition. (photo credit 6.1)

Crowley also liked Reymond’s companion, Alexis Pache (c. 1874–1905) of Morges, Switzerland, whom he found to be an unaffected and unassuming gentleman. Aged thirty-one, he was the only son among the four children of Charles Louis Frederick Pache and Henriette Emma (née Cart); his sisters were Helene Marie Suzanne, Marguerite, and Marie. 25 Like Reymond, Pache was a Swiss army officer, having become a dragoon lieutenant in 1894. 26 Between 1899 and 1901, he spent twenty months in the Boer War at Natal, fighting the British on behalf of the Boer government. He returned home to some celebrity: A three-part interview concerning his observations on the war and the respect he found for his indefatigable and chivalrous opponents ran in the Gazette de Lausanne , and was picked up from the London Times to the New Zealand Star . 27 Although lacking in climbing experience, he was energetic and adventure-loving, joining the expedition mainly for the opportunity to hunt in the Himalayas. 28 Indeed, Jacot-Guillarmod noted how excited he got seeing monkeys and other animals from the train to Darjeeling. 29 Pache also brought along several glass specimen vials to collect indigenous ants for Professor Auguste-Henri Forel (1848–1931), a distinguished Swiss psychiatrist and neuroanatamist who retired to devote himself to myrmecology. 30

AC also invited along Alcesti C. Rigo de Righi, the Italian manager of the Drum Druid Hotel on the Mall and proprietor of the Woodlands Hotel adjacent to the railway station. 31 The latter was Darjeeling’s leading inn when American humorist Mark Twain (1835–1910) visited in 1896, 32 and Baroness Mary Victoria Curzon of Kedleston (1870–1906), after nine days’ stay in 1900, raved about how “M. Righi took the greatest pains to see that everything was nice.” 33 Climber Charles Granville Bruce (1866–1939) noted that de Righi was “always ready to assist any traveller to the upper ranges,” 34 while English illustrator Walter Crane (1845–1915), visiting in 1906, remarked, “He occasionally entertained his guests by a lecture in the evenings, illustrated by photographic slides taken on the expedition.” 35 Although de Righi was a novice climber, he spoke Hindustani and Tibetan, which Crowley considered invaluable. Plus, “he spoke English like a native.” 36 Thus, de Righi became the expedition’s transport manager. Much like Guillarmod, de Righi also brought along his camera to document their historic climb. These five—Crowley, Guillarmod, Reymond, Pache, and de Righi—made up the party.

Drum Druid Hotel manager Alcesti C. Rigo de Righi. (photo credit 6.2)

It was raining so incessantly that Darjeeling’s average annual rainfall of 120 inches was already reached in July, and the downpour continued throughout the party’s nine days there. The rain was so persistent that they only caught fleeting glimpses of the famous view of Kangchenjunga. 37 On Tuesday, August 8, 1905, at 10:16 a.m., they marched in the pouring rain on their winding path through the countryside toward Kangchenjunga, with several thousand pounds of food, luggage, and camping equipment carried by an additional hundred porters. Even at this early stage, the expedition was plagued by problematic porters: because of the thin atmosphere at this altitude, it was a difficult haul. Several porters snuck off daily, taking with them days’ worth of rations, requiring one of the team to be designated to bring up the rear. The explorers also resorted to tactics like offering a pack of cigarettes to the first ten porters to reach the next day’s destination. To top it off, they discovered that the 130 porters they’d sent ahead had still not arrived; thus, de Righi went ahead to search for them. It was a sharp contrast to the dependable help they had on K2. 38

At the last possible moment, word arrived that they had received official permission to cross into Nepal, which was normally prohibited to Europeans; 39 this allowed them to take the most direct route to the mountain, marching north from the Singalila Range to the Yalung Valley. On arrival, the 130 porters supplied by the government dropped their supplies at the foot of the glacier and left, refusing to go any further. To the Tibetans, mountains were strongholds of the gods, and these porters feared offending them. Between this and the other defectors, this left them with eighty porters.

On August 21, Crowley left Pache in charge of Camp 1 while he ventured up the glacier and set up Camp 2 at 14,000–15,000 feet, about two miles from Kangchenjunga’s peak. Here, two pinnacles were visible, although clouds obscured the main peak, Kangchenjunga itself. The sight of their goal filled Crowley with excitement: He was in top shape, the weather was good, and the path looked easy. He was sure this ascent would make his adventure on K2 seem like a bad dream.

Guillarmod was not so optimistic. The sight of the glacier discouraged him: he had never seen one so tangled and torn, and the west ridge looked like it was constantly rained with avalanches. He declared this approach unclimbable, and objected to attempting it. That Crowley preferred this approach added more tension to what was shaping up to be a stressful expedition.

Crowley had good reason to choose this course: in 1899, Freshfield, based on his reconnaissance of the mountain, recommended the nearby ridge as a means of overcoming the steep glacier. In the view of the team that later surveyed the mountain in 1954, Guillarmod overreacted while Crowley formulated a reasonable, albeit optimistic, plan. 40

By the next day, Crowley had already picked out the site for Camp 3 with his binoculars. Heading west up the steep slopes, he set up camp in the heart of Kangchenjunga’s basin. From here, he could survey the surrounding landscape. The route to the summit appeared to be clear.

Later that day, from Camp 3 he could also see as Guillarmod and his men came up the ridge and set up their own camp. AC harangued Guillarmod for his failure to follow orders, while Guillarmod claimed Crowley had marked the path poorly and left him no choice but to take control of his own men. Such miscommunications typified the expedition.

Guillarmod and Crowley clashed again over the march to Camp 4. 41 Crowley wished to start early to take advantage of the clear weather; so he rose at 3 a.m. and prepared his men by six. Guillarmod, however, insisted he wait until eleven so the men could warm in the sunlight. “That’s absurd,” Crowley retorted, and set forth. He found the route steep and slick, more difficult than he expected. In a series of short sprints, the team reached the flat ridge at the top of the slope, the site for Camp 4. Crowley thought the spot was a little narrow. Looking up the hill, the only other likely campsite was another three hours’ climb. He noticed Reymond and Guillarmod were exhausted, and opted to set up camp where they were.

After putting a rope down the slope for the porters to retrieve supplies from below, he sent word to Pache: Camp 4 is established, move from Camp 2 to Camp 3. Crowley was surprised when Pache climbed up to Camp 4, reporting that de Righi was not sending up necessary supplies, and they were now low on petroleum and food. Owing to these conditions, some of the porters deserted; one of them, going off alone, had disappeared. Jacot-Guillarmod went down the next day to investigate, and discovered the missing man’s badly mutilated corpse where he slipped and fell on the rocks 1,500 feet below. Examining the remaining porters, Guillarmod noticed some of them exhibiting altitude sickness and ophthalmia, their eyes bloodshot and painful. 42

Leaving Guillarmod in charge of Camp 4, Crowley, Reymond and Pache advanced to Camp 5 at an elevation of 20,343 feet. Waiting for supplies that never arrived, a frustrated Crowley again observed how failure to follow orders stalled their progress. Finally, on August 31, the team pressed on. At this point, Crowley realized ascent would be more difficult than he initially estimated: the mountain was steep at this point, and sported many granite precipices.

With porters cutting steps out of the ice, they climbed quickly to a height of 21,000 feet. Crowley paused, watching small hunks of broken ice scuttle down the hillside as the workers hacked away. He noticed a few bits of snow also skimming along the surface. When a hiss like hot water coming to a boil reached his ears, he knew an avalanche was beginning. AC ordered the men to brace themselves on the steps, knowing they’d be safe there. They did as the sahib instructed. One porter, however, panicked and began untying his rope in order to sprint across the sliding snow. Crowley again instructed him to stay put. When he ignored the command, AC used the only swift and sure solution: He knocked the porter upside the head with the flat of his ax. 43

Panic far outstripped the size of the avalanche, and the snowslide passed them without incident. Nevertheless, the party called it a day and returned to Camp 5. There, gossip among the porters changed the snowslide into a cataclysm and the blow to the porter’s head into a violent assault. That night, several frightened men deserted, complaining to Guillarmod that Crowley was beating them. Crowley would later claim that the porters were exaggerating the incident during the avalanche. But Jacot-Guillarmod, despite the porters having been unruly and very difficult to keep in line, believed them. 44 Indeed, Reymond recorded in his diary that he and Pache had observed Crowley at Camp 5 beating old Penduck, alternately kicking him and hitting him with his alpenstock as the porter laid in the snow, howled, and pleaded with him to stop. 45 The doctor decided matters had gone far enough.

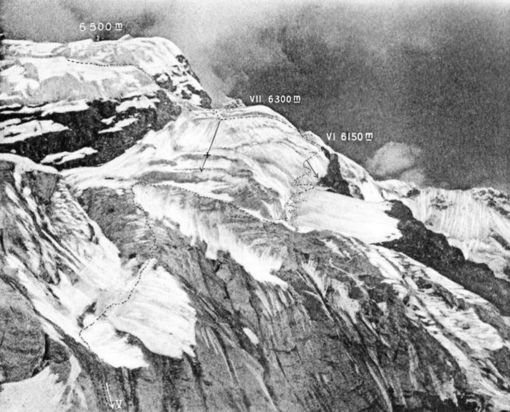

Photo of Kangchenjunga by Jacot-Guillarmod, showing the party’s route up the mountain and the location of several of its camps. The camp numbers differ from Crowley’s: VII is Crowley’s Camp 5, and VI is Camp 4. (photo credit 6.3)

The next morning, as Crowley and his remaining company prepared another attempt on the slope, Guillarmod unexpectedly ascended to Camp 5 with de Righi and his party behind him. What the hell are they doing here? Crowley wondered, dumbfounded. He thought they had supplies but, learning they had none, AC once again pondered: What the hell are they doing here?

The answer was simple: mutiny.

Jacot-Guillarmod had had enough. The unfollowed orders, fleeing porters, and hazardous ascent convinced him to hold a meeting of the expedition’s principals. The climbers voted to oust AC and make Jacot-Guillarmod leader. “You may be a good climber,” the doctor told Crowley, “but you’re a bad general.” 46 The doctor even convinced de Righi, who ascended with him, into backing this plan. Although hurt, Crowley merely scoffed, “There is no provision for this stupidity in our contract.”

“It is only a piece of paper,” Jacot-Guillarmod replied coolly; it was his right as initiator of the expedition. 47 Assuming command at 5 p.m. on September 1, 1905, the doctor declared the expedition over, effective immediately. Crowley watched helplessly as Jacot-Guillarmod wrested the expedition from his hands; watched as all the porters, with insufficient room for all of them at Camp 5, descended to take shelter behind the rocks at Camp 4; watched as Pache, his campmate, sided with Guillarmod. Only Reymond (at Jacot-Guillarmod’s request) remained with Crowley.

They’re fools , AC thought. None of them know the first thing about Himalayan climbing . And there they were, preparing to climb down even though night would fall before they finished. As his friends left, Crowley implored—to Pache in particular—to wait until morning, when it would be safer. “If you go now, you’ll be dead within ten minutes.”

Deaf ears turned away and started down the mountain. Crowley retired to his tent, Reymond thought, with the injured air of a deposed monarch.

Connected by one hundred feet of rope, Jacot-Guillarmod, de Righi, Pache, and three porters with crampons—Bahadur Lama, Thenduck, and Phubu 48 —began their descent, with Jacot-Guillarmod and de Righi in the lead. As they turned a sharp corner of the slope, a porter slipped. “No,” Pache cursed to himself in split seconds, “the descent has barely started.” He watched helplessly as the porter fell over the edge, taking the next porter in line with him. “No,” Pache lamented: “Seventeen porters just passed through here without a hitch.” By the time Pache realized he was tied to the same rope as the two falling porters, he was also plummeting down the slope, taking another porter with him.

Below, Guillarmod and de Righi saw their four comrades plunging toward them. Preparing to intercept their sprawling friends, they spread their legs, planted themselves on the path, and braced themselves. As the four falling bodies slid by, they caught one of them. The rope which encircled the waists of the other three snapped tight. For a moment, they stopped.

Then the snow beneath them slid.

A fifty-yard-wide avalanche of snow started down the hill, and de Righi slipped. Guillarmod held him with one arm while his other gripped his ax—the only thing keeping them in place. He held with all his strength, but the five men were just too heavy. Guillarmod’s fingers slid off the ax handle despite themselves, and the avalanche swept all six men down the mountain. Guillarmod tried to grab an ax in his path, but everything was happening too quickly; all he could do was paddle to keep on top of the sliding snow.

In five seconds, it was over: they fell into a crevice, and Guillarmod watched his friends vanish under the falling snow. Then darkness and debris engulfed him as well.

Breathing was difficult at first. He couldn’t move, and he wasn’t even fully conscious. Gasping for air, he realized he was cold, and then he realized what had just happened. Guillarmod pulled himself free by his rope and found de Righi at the other end, on top of the crevice. He was pinned down by Guillarmod on the one side of his rope and by their buried comrades on the other. Had Guillarmod died, he would have been trapped there and frozen to death. As it was, after Guillarmod freed him, he was so shaken he was unable to stand.

Guillarmod attempted to rescue the others alone. He tugged on the rope which ran vertically into the snow-filled crevice below, knowing four men were on the other end somewhere. With no tools with which to dig, he used his bare hands. Soon, de Righi joined in, but it was just too slow. The doctor cried out in desperation, “Help! Reymond, help! Bring ice picks!”

“What’s that?” Reymond asked.

“What?” Crowley asked with sour disinterest.

“It sounds like de Righi and Guillarmod yelling.”

He shrugged. “So? They’ve been yelling all day.”

Reymond still had his boots on. “I think I should go and look.”

“Well, send word back if you need help.” Crowley obviously didn’t mean it. He figured Reymond was deserting, too. He remained in his tent, drinking tea. When he received no word from Reymond, AC rolled over in his sleeping bag and fell asleep, alone at Camp 5.

So Crowley describes this incident. The account in Reymond’s diary differs: Hearing the cry for help, Reymond, who still had his boots on, ran out of their tent, looked over the edge, and saw Jacot-Guillarmod and de Righi pulling at a rope that disappeared into the snow at their feet.

“Where’s Pache?” Reymond shouted.

“Buried in the snow with three porters,” Jacot-Guillarmod replied. Reymond could hear the deep anguish in his voice. “Come on, hurry!”

Reymond ran back to the tent and reported to Crowley, “Pache and three porters have run into an avalanche.” Crowley didn’t move, but remarked that the stupidity of people could fill an entire avalanche. Not waiting for orders, Reymond packed food into a backpack, put on his crampons, and headed down the path. To his great surprise, Crowley did not follow. 49

Reymond looked like an angel at the top of the crevice, looking down on the doomed party and asking, “Do you need help?” After he rounded up axes and joined them in the pit, they dug at the tons of snow and ice that covered Pache and the others. They worked in turns, individually digging with an ax in the ever-deepening pit and hacking out more snow until white powder coated their bodies and their fingers felt like they were aflame. When darkness came with no sign of their comrades in the snow, they knew the truth:

Pache and the porters were already dead.

Crowley awoke the next morning and climbed down to Camp 4 to look around. He thought he heard voices, but saw no one. When he reached Camp 3, he found Guillarmod badly bruised and his back hurt; de Righi’s ribs were also bruised, and he complained of other injuries. Then he found out: Pache and his three best porters were dead at the bottom of an avalanche.

Anguish and anger mixed within Crowley: his rash comrades had died as the result of their ill-conceived coup. “The conduct of the mountaineers amounted to manslaughter. By breaking their agreement, they had assumed full responsibility,” he wrote bitterly. 50 Reymond recorded in his journal that Crowley, to the surprise of the others, explained that he thought the victims had been thrown on the rocks like the last porter, which is why he didn’t come to help the night before. 51 That evening, Crowley took Reymond’s place in de Righi’s tent (forcing Reymond into Jacot-Guillarmod’s), and the next morning, around 11 o’clock on September 3, AC left for Darjeeling. He wired his accounts to The Pioneer and Daily Mail , and awaited the rest of the party.

The others, meanwhile, stayed behind to recover the dead. Three days of digging finally uncovered the deceased climbers. A lama in the group said prayers over the bodies. and the porters lowered their three dead companions, arms crossed, into a crevasse and covered them with snow. “The god of Kangchenjunga took them,” they declared fatalistically, “and they will spend eternity near him.” They carried Pache to Camp 3, where fifty porters helped erect a memorial cairn. Reymond spent three days engraving Pache’s name and the date of his death onto a slab of granite. The moraine hillock where he died to this day is known as Pache’s Grave.

The tension on the mountain that led to Jacot-Guillarmod assuming control of the expedition spilled into the world’s newspapers at what the Alpine Club called “lamentable length.” 52 Initial news of Pache’s death was reported widely, including in the Manchester Guardian, Journal de Genève, Science , and the Alpine Journal . 53 Because Crowley returned to Darjeeling ahead of the rest of the party, his were the first press releases to reach print. He had been documenting the climb’s progress in a series of articles for The Pioneer titled “On the Kinchin Lay.” 54 His latest installment described the tragedy and placed the blame squarely on his teammates, saying that the accident occurred in the course of his team abandoning him on the mountain; they proceeded “ignorant or careless of the commonest precautions for securing the safety of the men.” 55 Crowley described sending Reymond to investigate the ensuing avalanche, and even admitted that he remained in his tent:

Reymond hastily set out to render what help he could, though it was perfectly out of the question to render effective aid. Had the doctor possessed the common humanity or commonsense to leave me a proper complement of men at Camp V, instead of doing his utmost to destroy my influence, I should have been in a position to send help. As it was I could do nothing more than send out Reymond on the forlorn hope. Not that I was over anxious in the circumstances to render help. A mountain ’accident of this sort is one of the things for which I have no sympathy whatever 56

Alexis Pache’s grave on Kangchenjunga. (photo credit 6.4)

This sparked a war of words between the expedition’s principals, beginning with a detailed rejoinder by de Righi, countersigned by Jacot-Guillarmod and Reymond, in the September 29 edition of The Pioneer . Regarding the most serious charges, de Righi wrote:

Mr. Crowley further says that we left him without men. Every coolie with him, owing I suppose to fear of the mountain and of Mr. Crowley, had bolted the night before, so that he only had with him Thenduck senior, who, after his treatment at Mr. Crowley’s hands and feet, begged of us to be taken down. This was the only man we deprived Mr. Crowley of; as of Mr. Pache deciding to come down with us (he was not persuaded by the Doctor), his servant, Bahadur Lama, came down with him, making thus our party up to six men. We, of course, could not refuse them, so the charge that we left him without effective help, our answer is, we only took one man who was sick and bruised. He further states that had the Doctor possessed the common humanity and common sense to leave him men he could have sent an effective rescue party. This Doctor Guillarmod was unable to do as no coolie then would stop with such a Sahib, who convinced his coolies to march with the business end of his ice-axe or the toe of his well shod boot. 57

In his final installment (penned the day after the accident but allegedly not edited in response to de Righi’s letter), Crowley conceded that his last report was written on the heels of the accident while in a charged emotional state and without all the facts. “I was under the (false) impression that the Doctor and Righi were on one rope, and the rest … on another. What I supposed to be the matter was that these five had been seen to fall over the cliffs on to the lower glacier.” So far, so good. However, his list of reasons for not rendering help after the avalanche shockingly concluded, “The doctor is old enough to rescue himself and nobody would want to rescue Righi.” The article ended with the following dig at de Righi: “It is only fair to add that on my return I found (in spite of the absence of the brilliant young manager) that the food and attendance at this hotel had very much improved, even to excellence.” 58

This drama replayed itself in Switzerland, when these stories were picked up and run by the Journal de Genève and Gazette de Lausanne et Journal Suisse . These include de Righi’s account, a detailed series on the climb by Jacot-Guillarmod, and conclude with Reymond’s account of the climb in the February 5, 1906, Journal de Genève . 59 These accounts maintained that Crowley lacked the skills necessary to lead the expedition effectively. The clash ended quietly, however, when Guillarmod threatened, if Crowley did not desist, to accuse him of fraud, sending a copy of Snowdrops along with the complaint. Crowley relented. In the months to follow, Jacot-Guillarmod would go on to report the tale of their expedition to the French Alpine Club, the Swiss Alpine Club, and the Geographical Society of Geneva. 60

In the end, the image that stuck not only with his peers in the climbing community but also with the general public was an unflattering portrait of Crowley painted by his own words, as quoted above. If his flippancy did not seem cold enough, his later letters commented that although it would have taken him only ten minutes to dress, he did not do so because there was no word from Reymond. Writing in the Daily Mail , Crowley added, “I am not altogether disappointed with the present results. I know enough to make certain of success of another year with a properly equipped and disciplined expedition.” 61 Furthermore, the attacks on the Alpine Club couched within his narrative further drew the ire of fellow climbers. As one person wrote of Crowley’s first article for The Pioneer:

From the tone of it, I judge him to be a disappointed candidate for membership of the Alpine Club, to which I may add, I have not the privilege of belonging. The sport of mountaineering will certainly suffer no loss if Kinchenjunga permanently effaces this polished individual. 62

In the end, Crowley painted himself as a detached and uncaring leader who simply did not want to rescue his comrades.

Kangchenjunga was history. The crushing, embittering experience scarred Crowley: he would never again make a climb of any consequence, and Kangchenjunga phobia would haunt him even in his last days.

Long after this tragic attempt, the Five Peaks remained elusive: Raeburn and Crawford’s 1920 attempt was cut short because they were inadequately equipped. In 1929, snowstorms at 24,272 feet turned back Bauer’s expedition. The following year, Dyhrenfurth lost a porter in an avalanche and abandoned the peak in favor of a smaller mountain. Bauer tried again in 1931 but gave up at 25,500 feet when he encountered an unclimbable slope. Cooke’s 1937 expedition failed similarly, while Frey died in his 1951 attempt with Lewis.

Not until 1954 did John Kempe’s expedition successfully conduct reconnaissance of Kangchenjunga’s southwest approach, paving the way for the British expedition that conquered the mountain in 1955. 63

And not until the twenty-first century—a century after this fateful climb—have Crowley’s mountaineering accomplishments been seriously reevaluated. Colin Wells, author of A Brief History of British Mountaineering (2001), called him in 2002, “one of the most accomplished and talented climbers in his era,” and quoted Mick Fowler, who repeated many of Crowley’s Beachy Head climbs eighty-five years later, as saying admiringly,

Crowley was outrageous! He was obviously good; something of a star rock climber, in fact.… He was light years ahead of his time in his attitude to tackling vertical chalk cliffs. The ground he covered was without doubt amongst the most technically difficult in Britain, but his achievements were never really appreciated in his lifetime. 64

Similarly, Isserman, Weaver, and Molenaar conceded in Fallen Giants ,

From far outside the privileged purlieus of the Alpine Club and the Royal Geographical Society (who between them did in fact conspire to diminish or even erase Crowley’s achievement), he found his way to the world’s second- and third-highest mountains and somehow discerned and reconnoitered the routes by which they would first be climbed. 65

Finally, Canadian Alpine Journal editor Geoff Powter noted in Strange and Dangerous Dreams , “Crowley’s rehabilitation in climbing circles has been as dramatic as it has been elsewhere,” 66 due in no small part to the fact that the sport’s vanguard and rock stars of today, living on the edge, share more in common with Crowley than they do with his staid and proper peers.

Life looked pretty grim. Crowley was a man who had climbed among the highest mountains in the world, only to have his first leadership snatched from him and his men buried in ice. As a poet, he had published so many books that his collected Works were available, even though the originals never sold. He had traveled around the world, and was now halfway around it again and finding it stale. And he was a master of magic who chose to forget his experience in Cairo. Now on the verge of his thirtieth birthday, life stared him in the face.

What next?

Empty and lost, he cabled Rose to join him in India and wrote soul-searching letters to his brother-in-law. Everything had soured, seemed stale. Even his poetry, which he had all but forgotten lately, was doubtful:

I have thought of trying serious writing again, but I am 30 and a proud Papa. Shelley and Keats never touched 30—that day is over for me. I think some small bits of work are classical with theirs, I must leave it at that. Anyway, I hope I shan’t simply go bad. At least I am certain to avoid the blunder of making a good thing and copying it forever. 67

The only thing remaining was the truth that he had realized back at Cambridge, when he grasped for something in the world that could stir him: magic. He realized he had to change the world. Thus, The Sword of Song became his manifesto, and he wrote eagerly to Kelly:

This book has been boycotted by English publishers and printers. I am in arms against a world, but after five years of folly and weakness, miscalled politeness, tact, discretion, care for the feeling of others, I am weary of it. Did Christ mince his words with the Pharisees? I say today to hell with Christianity, rationalism, Buddhism, all the lumber of the centuries. I bring you a positive and primaeval fact, magic by name; and with this I will build me a new Heaven and a new Earth. I want none of your faint approval or faint dispraise; I want blasphemy, murder, rape, revolution, anything, bad or good, but strong. I want men behind me, or before me if they can surpass me, but men, men not gentlemen. Bring me your personal vigour; all of it, not your spare vigour. Bring me all the money you have or can force from others. If I can get but seven such men, the world is at my feet. If ten, Heaven will fall at the sound of one trumpet to arms. 68

By these words he would lead the rest of his life.

Crowley kept himself busy waiting for Rose and Lilith to arrive on October 29. He studied Persian, stayed with a maharaja in Moharbhanj, sacrificed a goat to Kali, visited his friend Edward Thornton, and went big-game hunting. Traveling to Calcutta, he also went to the infamous Culinga Bazar on October 28 during a boisterous holiday festival. At 10 o’clock in the evening, Crowley paused on the dark streets of the Bazar to revel in the fireworks and celebration until, despite himself, he stopped enjoying it. Amidst the noise and excitement, he felt uncomfortable.

He was being followed.

In an effort to shake his pursuer, Crowley ducked into an alley. Trouble followed him in the form of six figures. AC pressed into the shadows and held his breath, hoping his mountain tan and his dark clothes would conceal him until the throng passed. Just in case, he placed a tense hand on the Webley revolver in his coat. The first three walked right by him and, for a moment, he thought they hadn’t noticed him.

Then they closed in. Strong hands pinned Crowley’s arms to his sides while others searched his pockets. “Unhand me!” he barked, hoping an authoritative Englishman’s voice would frighten them off. In the glimmer of a distant flare, he caught the glint of a blade and realized his life was worthless in this back alley. His hand, still on the Webley, automatically drew the gun from his pocket and tightened around its trigger. The flash captured the sight of four white-clad figures dropping back and running. Then he found himself in silent darkness. 69

In the pulse-pounding moments that followed, it never occurred to him that a gunshot could pass unnoticed among noisy fireworks. Instead, he frantically imagined the worst: crowds would soon gather to investigate the commotion. The police would frown upon an Englishman—a foreigner—shooting someone in an alley. He pictured himself in prison somewhere, never to be seen again, and desperately sought a solution.

Recalling how he passed unnoticed on the streets of Mexico City, he thought to use that magic to get him out of this fix. Closing his eyes and calling on his holy guardian angel for protection, he cast a spell of invisibility upon himself and slipped down the alley, past the crowds, out of sight.

“Go to your room,” Edward Thornton, groggy with sleep, told him that night. “Go to bed. Come around in the morning and I’ll take you to the right man.” The right man was a solicitor named Garth, who officially advised Crowley to go to the police with his story. “You’d be acquitted, of course. But you’d be kept hanging about Calcutta indefinitely. An unscrupulous man might hold his tongue and clear out of British India p.d.q.” 70 Crowley waited two days before deciding to take action. He didn’t even know if the gunshot had struck anyone.

Rose arrived that day with their child, and Thornton threw them a dinner party that night. Throughout the meal, Thornton caught Crowley’s eye, gesticulated, and held up two fingers. Crowley simply looked back blankly. Thornton finally took him aside and explained: the bullet had struck two of his assailants, who confessed to the crime. The Standard carried the story the next morning; a reward was offered for the apprehension of the gunman. Ironically, the same issue featured an interview with AC as leader of the Kangchenjunga expedition. “Get out,” Thornton advised, “and get out quick.”

Heeding Thornton’s advice, Crowley looked at Rose and asked her, “Which will it be: Persia or China?”

“I’m tired of Omar Khayyam,” she remarked. “Let’s go to China.”

Rangoon began their journey. Crowley checked Rose and Lilith into a hotel while he visited Ananda Metteya, formerly known as Allan Bennett. They discussed the need for a common language if magic were ever to be studied scientifically, concluding that the system most accessible to Westerners was the kabbalah. It convinced Crowley of the importance of tabulating all systems of mysticism and religion according to the ten spheres and twenty-two paths of the Hebrew Tree of Life. Three days later, on November 6, Bennett had to return to the monastery per its rules. Following Allan’s advice on writer’s block, Crowley wrote “The Eyes of the Pharaoh” and what would form chapters I through XX of The High History of Good Sir Palamedes the Saracen Knight , a versified account of the path of initiation. The effort to write even this much, however, was stupendous.

On November 15, the Crowleys boarded the steamship Java for Mandalay. An artistic and intellectual vacuum within, Crowley spent the voyage leaning over the railing, watching the crests the boat cut into the water, watching the flying fish dancing along the surface, and trying to wrench some poetry out of himself. Finally, in his journal, he recorded, “the misery of this is simply sickening;—I can write no more.” 71

By November 29 they reached Bhamo, forty miles from the Chinese border. It marked a new phase in his life. Over the next months, his mundane existence became a series of bizarre adventures while his spiritual life became a simple and stellar affair, yielding to no interference from the mundane world no matter how crippling.

From Bhamo, the three Crowleys, their porters, and Lilith’s nurse began a leisurely journey toward Tengyueh (now called Tengchung), China. All the while AC brooded about the anomie and purposelessness he felt ever since Kangchenjunga. Then, on their fourth day from Bhamo, something happened to snap AC out of his existential crisis.

Having crossed the river that marked the Chinese frontier, they climbed out of a ravine with Crowley bringing up the rear to discourage the porters from straggling. At one point, Crowley dismounted his Burmese pony to walk and stretch his legs. Once adequately limbered, he tried to mount the pony. The beast, however, reared and sent them both down a forty foot cliff. Laying on the ground, looking up at the length of their fall, Crowley waited for the pain of his broken body to kick in. When it never did, he realized he was unharmed and marveled that both he and the horse escaped without a scratch. In that moment, he recalled all his narrow brushes with death: from the bomb he made at age fourteen to the muggers in Calcutta, he concluded his charmed life was being preserved for a greater purpose. It resolved his existential crisis.

At that moment, Aleister Crowley achieved the rank of Exempt Adept (7°=4°), the highest grade of the Second Order. With this illumination came a resolve to resume magical work. Daunted by his perceived role as the world’s greatest magus, Crowley confided in Clifford Bax:

It is very easy to get all the keys, invisible and otherwise, into the Kingdom, but the keys are devilish stiff, some of them dampered. I am myself at the end of a little excursion of nearly seven years in Hell, and the illusion of reason, which I thought I had stamped out in ’98, was bossing me. It has now got the boot. But let this tell you that it is one thing to devote your life to magic at 20 years old, and another to find at 30 that you are bound to stay a Magus. The first is the folly of a child; the second, the Gate of the Sanctuary. 72

On February 11, Crowley pledged to conduct a magical retirement even as they marched across China. He devoted the next three days to studying the Goetia for inspiration, then decided once and for all to contact his holy guardian angel. To this end, he decided to recite the Goetia ’s Preliminary Invocation every day. Of paramount importance was to perform the invocation daily, unfailingly. Rain or shine, tired or rested, good or bad, he had to do it.

He began on February 16, typically doing the invocation, which he called Augoeides, after Bulwer Lytton’s term for the holy guardian angel, on the astral plane, performing the rite in his imagination as he rode across the countryside on his pony. He maintained his resolve, performing the ritual every day until June 7, when he could continue no longer.

China’s Boxer rebellion was well underway when, at the beginning of January 1906, the Crowleys stayed at Tengyueh. On January 23 they reached Yungchang (what is now Paoshan), where the mandarin Tao Tai treated them to a twelve-hour banquet. Chinese New Year followed two days later.

After crossing the Mekong river on January 26, Crowley noticed that all his porters smoked opium in their free time. Although his previous exposure to the drug through Bennett had been fruitless, Crowley bought an opium pipe to learn about the fashionable drug that wealthy and intellectual Europeans flocked to the far and middle east to sample. After five hours and twenty-five pipes, AC experienced neither euphoria nor tranquility. Regardless, his muse returned, and he wrote “The King Ghost” and “The Opium Smoker.”

From there, the next two months’ journey took them to Yunnan, Mengtsz, Manhao, Hokow, Laokay (now part of northern Vietnam), Yen Bay, and the capital, Hanoi, “but only stayed for lunch.” 73

Toward the end of March, AC decided they would return home by two separate routes. Crowley wished to stop in America and seek out backers for another Kangchenjunga expedition while Rose retrieved their hastily abandoned luggage from Calcutta, returning to England via the continent. Rose was very annoyed about being cast off in China with their young daughter to return home alone. Crowley reasoned that, being wanted in Calcutta, he couldn’t return there with her. She finally agreed, with the intent of staying with her father when she arrived in Scotland. She needed his help because she was three months pregnant.

Meanwhile, her husband, unknown to her, was on his way to Shanghai to look up Elaine Simpson, the former Soror Fidelis. He arrived on April 6. There, he read tarot cards for Elaine and her friends. In private moments, Crowley and Elaine discussed The Book of the Law . She read it and, much to Crowley’s chagrin, believed it to be a prophetic book; he was hoping she would denounce it and thus relieve him of the role of prophet, a burden that the book called for him to assume.

Crowley asked her to help him invoke Aiwass and speak to him. She agreed, and two days later they conducted the ceremony. In what would become Crowley’s preferred method, he summoned Aiwass while Elaine looked for him on the astral plane. Aiwass appeared to her as brilliant blue with a wand in hand. “He has followed you all along,” Elaine explained her impressions of him. “He wants you to follow his cult.” Crowley instructed her to take his wand. When she did, Aiwass turned into brilliant light and dissipated. “He seems to be tangled in a mesh of light, trying to escape.”

“Tell him that if he goes away, he cannot return,” Crowley instructed.

“He has a message: ‘Return to Egypt, with same surroundings. There I will give thee signs. Go with the Scarlet Woman, this is essential; thus you shall get real power, that of God, the only one worth having. Illumination shall come by means of power, pari passu … Live in Egypt as you did before. Do not do a Great Retirement. Go at once to Egypt: money troubles will be settled more easily than you think now. I will give you no guarantee of my truth.’ Then he turns black-blue, and says, ‘I am loath to part from you. Do not take Fidelis. I do not like the relations between you; break them off! If not, you must follow other Gods … Yet I would wish you to love physically, to make perfect the circle of your union. Fidelis will not do so, therefore she is useless.’ ” 74

Satisfied with the ritual and the messages they received, they purified the area and finished. Despite Aiwass’s suggestion that Elaine make love to Crowley, she lived up to her magical motto and remained faithful to her husband. On April 21, Crowley left Soror Fidelis and sailed for America on the Empress of India . While they would remain in touch—in 1929, Crowley would note “My old and dear friend Fidelis wants me to go to Frankfurt” 75 —their bond would never be as strong as during their alliance in the GD years.

On April 24, while his ship docked at the Japanese port of Kobe, Crowley dutifully performed his invocation on the astral plane. This time, a vision appeared to him. In it, he entered a room in which a naked man was nailed to a cruciform table. About this table sat a group of venerable sages, busily eating the flesh and drinking the blood of the naked man. A voice told Crowley that these sages were the adepts he would someday join. As the vision continued, Crowley entered a filigreed ivory hall, a square altar in the center its only contents. “What wouldst thou sacrifice upon the altar?” the voice asked.

Crowley replied, “I offer all save my will to know Augoeides.” Knowledge and conversation of one’s holy guardian angel, after all, was the goal of all magic. At least as far as he knew. Looking about, Crowley realized he stood before the Egyptian gods, their forms so immense he could only see up to their knees.

“Would not knowledge of the gods suffice?”

Crowley was adamant. “No.”

“Thou art critical and rationalistic.”

The magician apologized for his blindness, kneeling at the altar and placing both hands upon it, right over left. A luminous figure clad in white appeared before Crowley, placing his hands upon the magician’s, then spoke, “I receive thee into the Order of the Silver Star.”

With that, Crowley returned to earth in a cradle of flame. The Secret Chiefs had accepted him as one of them, a member of the Third Order—those grades that awaited beyond the highest ones in the GD; those reserved for the Secret Chiefs. He worried whether he was ready for the demands of the job. On April 30 he wrote in his journal:

It has struck me—in connection with reading Blake—that Aiwass, etc. “Force and Fire” is the very thing I lack. My “conscience” is really an obstacle and a delusion, being a survival of heredity and education. Certainly to rely on it as an abiding principle in itself is wrong. The one really important thing is the fundamental hypothesis: I am the Chosen One. All methods will do, if I only invoke often and stick to it. 76

No matter what else might happen, he had to prove himself by invoking often; otherwise, he would lose everything. Such was his understanding. What he didn’t know at the time was that, if he did stick to it, he would have to lose everything anyway.

As he sailed, Crowley’s muse moved him again, and he wrote “The True Greater Ritual of the Pentagram” and worked on commentary to The Book of the Law . The thought of returning to his wife and family also inspired him to compose “Rosa Coeli,” the third in his cycle of poems to Rose.

The Empress of India reached Vancouver, British Columbia, in twelve days; he had just missed the earthquake and fires that gutted San Francisco on April 18. From Vancouver, Crowley traveled east across the continent, passing through Calgary, Winnipeg, and Toronto. Across the border in the United States, Niagara Falls impressed him. On May 15 he reached New York City, fatigued by travel. After ten days of restaurants and theaters, he found no one willing to invest in a Himalayan climb and sailed for England on May 26.

Arriving at Liverpool on June 2, Crowley picked up his mail, read the telegram, and his life fell apart.

His daughter Lilith was dead.