Staring at the letters from his mother and Uncle Tom, Crowley was stunned. Lilith dead? Unbelievable, yet the facts were all there: she didn’t even live long enough to reach London. Lilith Crowley had died of typhoid in Rangoon. Jewell, in one of his callous moments, remarked that Nuit Ma Ahathoor Hecate Sappho Jezebel Lilith Crowley actually died of acute nomenclature.

Despite the heartache, Crowley struggled to recite the preliminary invocation, which he had sustained for the past four months. A sad robot, he reaffirmed his oath to persevere no matter what, offering everything that remained of his life. He wandered the streets of London, emptily running through the words in his head. June 7, on the train to Plymouth where Rose awaited, was the last time he was able to complete the conjuration. When at last he saw his wife, they fell sobbing into each others’ arms. The couple stumbled around—nervous, weak, and weeping—for the next two days.

In the midst of this misery, Crowley discovered that Rose had become an alcoholic. Desperate for something on which to blame his misfortune, he convinced himself that Lilith died because Rose, too drunk to properly sterilize a baby bottle, fed her with a contaminated nipple. But how could he blame his Rose of Heaven? The fault was not hers but the alcohol’s. And the alcoholism he blamed on her family. Tellingly, he never pointed the finger at himself for leaving his pregnant wife and infant to make their own way home from the Far East while he returned in literally the opposite direction.

Crowley’s health declined into a series of illnesses: after doctors removed an infected gland from his groin, his right eye required a series of operations, all unsuccessful. Neuralgia and an ulcerated throat then set in and remained with him most of the year. Life’s miseries left him stunned and numb, sleeping much of the time.

Then, like an angel come to put his life back on track, George Cecil Jones, Exempt Adept (7°=4°) of the Second Order, arrived on June 23 to discuss Crowley’s work. They did so for the next two days, after which Jones advised Crowley to go on a Great Magical Retirement, albeit close to home so he could be reached by telegraph if necessary. The visit eased some of Crowley’s sorrow, and helped him concentrate again on the Great Work. On July 11, three days after he entered a nursing home for an operation, Crowley resumed daily recitation of the Augoeides invocation.

Crowley left the nursing home on July 25 and, the day after, went to stay with Jones. They continued to discuss and compare their magical experiences, and the following day, Jones used a modified version of the GD’s Adeptus Minor (5°=6°) ritual to initiate Crowley: Bound upon the Cross of Suffering, AC once again spoke the words, “I, Perdurabo, a member of the Corpus Christi, do hereby solemnly obligate myself to lead a pure and unselfish life …” as he had done before Mathers in Paris six years ago. However, the ritual was more than mere repetition. It was a potent synthesis of their independent magical work, taking the ceremony to undreamed levels and inspiring him like never before. Thus began a remarkable phase of Crowley’s work, two ex-GD members collaborating on mysteries their parent order scarcely imagined.

On July 29 they started to think about founding a new magical order.

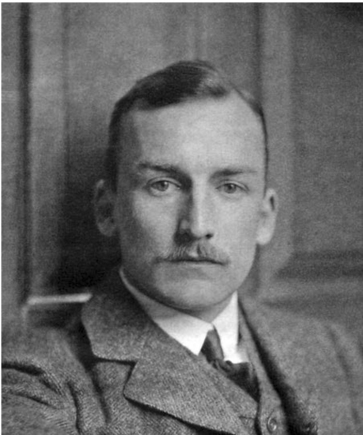

John Frederick Charles Fuller (1878–1966) shared much with Crowley. He was the son of an Anglican cleric—Rev. Alfred Fuller (1832–1927), formerly the Rector of Itchenor 1 —and, having a dreamy and introspective childhood, grew up later than most. He also attended Malvern and, like Crowley, learned to loathe it. In 1897, when Crowley began his third year at Cambridge, Fuller’s parents sent their son to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. The college nearly turned the boy down because he was too skinny, but accepted him on probation on August 30. He graduated a year later and joined the 43rd Infantry.

He spent the Boer War (1899) immersed in two hundred books on religion, philosophy, and other subjects and, while stationed in India in 1903, studied Hinduism, yoga, the Vedas , and the Upanishads . After reading Havelock Ellis’s Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1903) and E. N. Huston’s A Plea for Polygamy (1869), sexual freedom became one of his causes. Fuller believed that mankind needed to tear off the “mystic fig leaf … and stand naked and sublime in all the glory and consummation of perfect Nature.” 2 In 1905 he begged his mother not to tell his father, the cleric, that he had just contributed the first of what would be many articles to the Agnostic Journal; 3 it was his first overt statement of apostasy from the creed of his upbringing. The second was his essay on Crowley’s works, which he wrote during the hot summer of 1905. The Star in the West (1907) would prove to be the first and only entry into Crowley’s contest for the best essay on his works. Throughout, it shamelessly praised the poet: “It has taken 100,000,000 years to produce Aleister Crowley. The world has indeed laboured, and has at last brought forth a man.” 4 The praise, however, was not shallow. Fuller considered Crowley to be England’s greatest living poet, and believed it all his life.

John Frederick Charles Fuller (1878–1966), Frater Non Sine Fulmina. (photo credit 7.1)

In October 1905, Fuller developed a record case of typhoid that lasted seventy days. On February 14, 1906, a medical board recommended an eight-month leave of absence. That April, he was discharged and sent home for a year’s sick leave. He wrote to Crowley about these events, and AC responded with his first letter to Fuller in nearly a year. Arriving August 8, 1906, it read:

I am sorry to hear of your enteric fever, but fate has treated me even worse; for after a most successful trip through China without a day’s illness for any of us, our baby girl died of that very disease on the way home. 5

By mid-August they arranged their first face-to-face meeting at the Hotel Cecil. Under Crowley’s influence, his interest in the occult blossomed into fascination, and he plunged into its study. Likewise, Fuller’s knowledge of Hinduism impressed AC, spurring him on to study as well. Despite his daughter’s death, his pregnant wife’s alcoholism, and his own illness, Crowley devoted himself to magic.

At this point, not one but two individuals answering to the name “Lola” entered Crowley’s life. The first was a nickname for Vera Snepp, whom Crowley, frustrated by Rose’s alcoholism, took as a mistress during visits with Jones in Coulsdon, Surrey. She acted under the name Vera Neville, 6 and was one of the most beautiful English women he had ever met. AC chronicled their affair in poems which would later become part of Clouds without Water (1909):

Lola! now look me straight between the eyes.

Our fate is come upon us. Tell me now

Love still shall arbitrate our destinies,

And joy inform the swart Plutonic brow. 7

She would also become the dedicatee of Gargoyles (1906) and the model for the Virgin of the World in “The Wake World.” 8

The other Lola appeared in September when Rose gave birth to Crowley’s second daughter, whom he named Lola Zaza, presumably after his mistress. The occasion was hardly glad. The infant was sickly and, for her first three days of life, so inactive that they often feared she was dead. At three weeks of age, bronchitis nearly killed her. Given what modern medicine knows about the deleterious effects of maternal alcohol consumption on a fetus, frailty and low birth weight are unsurprising; but in the Edwardian age the Crowleys could only marvel at their continued misfortune.

With Rose and the baby recovering in Chiselhurst, Crowley returned to Coulsdon to study with Jones and recuperate from his own ailments. Under these conditions, his health returned “suddenly and completely.” As with his health, Crowley also recovered his magical impetus. On September 21, he marked thirty-two weeks’ performance of Augoeides, with only a brief break during his crisis in June.

The following day, Jones and Crowley celebrated the autumnal equinox. For the occasion, Jones adapted the GD Neophyte (0°=0°) ritual, retaining and streamlining its potencies while eschewing unnecessary details. The result was a powerful formula of initiation for their proposed mystic society. Into the typical ceremony of testing and purifying a candidate they introduced spiral dancing and ritual scourging; and rather than binding the candidate to a cross as in the Adeptus Minor (5°=6°) ceremony, the candidate was pinned down and a cross cut on his chest. Jones asked Crowley to write the ceremony in verse form; the result was “Liber 671,” later dubbed “Liber Pyramidos.” 9

After slight alterations by both magicians, they tested the revised ritual on October 9. Crowley considered the result among the greatest events of his career: he attained the knowledge and conversation of his holy guardian angel. He experienced Shivadarshana , the vision of Shiva. He entered the trance of samadhi , union with godhead. After six years of false starts, he succeeded at the Abramelin operation. In response, Crowley “thanked gods and sacrificed for Lola” 10 —his lover, not his child.

While his spiritual life soared with its victories, his personal life crumbled under the stress of its burdens: Lilith’s death, Rose’s alcoholism, and Lola Zaza’s frail grip on life. On November 4 he wrote in his diary, “Dog-faced demons all day. Descent into Hell.” In magical terms, he had plumbed the depths of the Ordeal of the Abyss, a magical rite of passage designed to obliterate the magician’s ego by destroying all he held dear: those physical attachments that Buddha blamed for reincarnation; one’s selfishness, or sense of self. The magical text “Liber Cheth” later described this spiritual desert:

Then shall thy brain be dumb, and thy heart beat no more, and all thy life shall go from thee; and thou shalt be cast out upon the midden, and the birds of the air shall feast upon thy flesh, and thy bones shall whiten in the sun.

Then shall the winds gather themselves together, and bear thee up as it were a little heap of dust in a sheet that hath four corners, and they shall give it unto the guardians of the Abyss.

And because there is no life therein, the guardians of the abyss shall bid the angels of the winds pass by. And the angels shall lay thy dust in the City of the Pyramids …

And behold! if by stealth thou keep unto thyself one thought of thine, then shalt thou be cast out into the abyss for ever; and thou shalt be the lonely one, the eater of dung, the afflicted in the Day of Be-with-Us. 11

Mathers had never warned him about it, and he couldn’t have, because he never advanced this far along the spiritual path. But Crowley now realized the truth: only one who released everything was light enough to cross the desiccated yaw of the Abyss, to surpass the Second Order’s highest grade of Exempt Adept (7°=4°) and follow the path of the Secret Chiefs and their Great White Brotherhood. By contrast, those who clung to some vestige of their former lives were mired forever in the Abyss, doomed as one of the Black Brothers who elevated their egos to the godhead. “I cannot even say that I crossed the Abyss deliberately,” Crowley wrote, illustrating that, although few ever advanced this far, the terrible ordeal was an eventuality for all magicians, a consequence of one’s earliest oaths. “I was hurled into it by the momentum of the forces which I had called up.” 12

Thus Crowley surrendered all he valued, knowing that if he did not, the gods would wrench it from his feeble hands. When British Customs seized Philippe Renouard’s shipment of AC’s latest (Alexandra) , deemed it obscene, and destroyed all copies, it seemed like a test of his resolve.

This illumination also recalled the warning written in the repugnant third chapter of The Book of the Law:

Let the Scarlet Woman beware! If pity and compassion and tenderness visit her heart; if she leave my work to toy with old sweetnesses; then shall my vengeance be known. I will slay me her child: I will alienate her heart: I will cast her out from men: as a shrinking and despised harlot shall she crawl through dusk wet streets, and die cold and an-hungered. 13

And he understood. The gods had killed Lilith because his attachment to her was impeding his progress in the Great Work. The gods killed her because Rose had failed in her role as Crowley’s magical partner. The gods killed her as a warning. In that moment, Crowley realized the cosmos played by very tough rules.

On the eighth anniversary of his initiation into the GD—his spiritual birthday—Crowley dedicated the epilogue of his collected Works to Jones, who had acted as Kerux at his admission to that group:

Eight years ago this day you, Hermes, led me blindfold to awake a chosen runner of the course. “In all my wanderings in darkness your light shone before me though I knew it not.” To-day (one may almost hope, turning into the straight) you and I are alone. Terrible and joyous! We shall find companions at the End, at the banquet, lissome and cool and garlanded; companions with a Silver Star or maybe a Jewelled Eye mobile and uncertain—as if alive—on their foreheads. We shall be bidden to sit, and they will wreathe us with immortal flowers, and give us to drink of the seemly wine of Iacchus—well! but until then, unless my heart deceives me, no third shall appear to join us. Indeed, may two attain? It seems a thing impossible in nature.… 14

The Silver Star and Jeweled Eye in the triangle were symbols of the Third Order, the A A

A , the Great White Brotherhood of Secret Chiefs. Crowley considered himself and Jones to be alone among the most advanced adepts in the world. However, lacking a third initiate to complete their founding triad (à la Westcott-Woodman-Mathers), they could not begin their new order.

, the Great White Brotherhood of Secret Chiefs. Crowley considered himself and Jones to be alone among the most advanced adepts in the world. However, lacking a third initiate to complete their founding triad (à la Westcott-Woodman-Mathers), they could not begin their new order.

On December 10, Jones served as harbinger for the Secret Chiefs, who again invited Crowley to join their ranks in the Third Order. No longer was he Frater OY MH, as he was known as an Exempt Adept (7°=4°), the seventh in the magical hierarchy and fourth from the pinnacle. He had crossed the Abyss and had advanced to the eighth level, previously considered unattainable by corporeal beings. Or, as Jones put it, “OY MH is 8°=3°.”

“And Mollie Lee rhymes with both,” he replied flippantly. Nevertheless, Jones insisted that, as 8°=3°, Crowley had not only attained the grade of Master of the Temple but had become the Master: the next Buddha, the logos, the prophet of a new age. He thereupon performed a ritual to consecrate Crowley a Master of the Temple. Although Crowley still considered himself unfit for the honor, the ritual made him feel like a genuine master.

The next day—when Crowley went to Bournemouth and placed himself under a doctor’s care for throat trouble—he received a letter from Jones, reiterating the topic of their meeting:

How long have you been in the Great Order, and why did I not know? Is the invisibility of the A A

A to lower grades so complete?

15

to lower grades so complete?

15

Crowley found his attainment increasingly difficult to deny.

As he recuperated, he recalled his conversation with Allan Bennett about the value and necessity of the kabbalah as a universal language for magic. Crowley sat down on December 15 with the table of correspondences that Bennett had left him prior to his move to Ceylon and began to expand the entries. For the first four days, he devoted only eight hours to the project, but soon began to work on it in larger doses. On Christmas, for example, he spent all day and night working. Only a heated discussion between Crowley and Jones on the nature of truth and magical attainment, as discussed in Crowley’s new essay “Amath” 16 (Hebrew for “truth”), diverted him. The completed work tabulated all the information taught by the GD, plus the knowledge Crowley had acquired in his trips to the world’s sacred sites; it would be published as 777 in 1909.

On January 29, 1907, Crowley left Bournemouth and returned home.

Lola Zaza Crowley took a downturn on Friday, February 15. Since her first frail days, she had developed respiratory complications that required a nurse to watch over her. She was on oxygen, and the doctor ordered that only one person be permitted in the room with her at a time.

Rose’s mother, Blanche Kelly, came in to visit the baby that Saturday. Crowley disliked his mother-in-law, and when she broke the rules about Lola’s care, a row erupted. In the end, Crowley threw her out of the flat and, in his mind, saved the baby’s life. Alas, combined with Rose’s drinking and his own affair, the incident only contributed to marital discord.

The evening started out like any other: Crowley walked down to Stafford Street to his favorite haunt, chemist E. Whineray, who supplied unusual ingredients for his ceremonial perfumes and incenses. Whineray’s bald head and large eyes—shining alike with laughter and cynicism—reminded Crowley of an owl. “He knew all the secrets of London. People of all ranks, from the courtier and the cabinet minister, to the coachman and the courtesan, made him their father confessor,” Crowley wrote. “He understood human frailty in every detail and not only forgave it, but loved men for their weaknesses.” 17 Like Eckenstein, he could see through Crowley and understood him—a trait on which Crowley depended.

Edward Whineray (1861–1924) was born in Ulverston, Lancashire, about a year after saddler William Whineray wed Betsy Hodgson. 18 He became an apprentice of the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain in 1875 and helped found the Chemists’ Assistants’ Union in 1898, after which he became managing director at pharmaceutical chemists W. E. Lowe Co. Ltd. on 8 Stafford Street, building a distinguished clientele. 19 Crowley claims that Whineray’s shop appears in novelist Robert Smythe Hichens’s Felix (1902), although Crowley fails to provide any details. In fact, Hichens’s unnamed fictional chemist on Wigmore Street discreetly dispenses morphine to society ladies, even in the dead of night. 20 In his only review published in The Equinox , Whineray wrote of Chronicles of Pharmacy , “To the student of the occult it ought to appeal strongly, as the author gives a long list of drugs used in religious ceremonies in different ages.” 21

This day, Whineray had something new for him. The Right Honourable George Montagu Bennet (1852–1931), 7th Earl of Tankerville and Lord Ossulston, sought an introduction. 22 A thirteenth-generation descendent of princess of England Mary Tudor (1496–1533), Bennet was the second son of Charles Augustus Bennet (1810–1899) and Lady Olivia Montagu (1830–1922). He lived a colorful life, beginning as a Royal Navy midshipman in 1865, until severe sea-sickness compelled him to resign. From there, he won the Ottley prize for drawing at Radley College, was a member of the Rifle Brigade from 1872, and aide-de-camp to the Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland. His older brother Charles’s death in 1879 of cholera in Pahawur, India, left him heir to the peerage, so he assumed the title of Lord Bennet and left the army. Next, he went ranching in the western United States, where he was friendly with Teddy Roosevelt (1858–1919). In 1892 he met and befriended American Methodist gospel singer and evangelist Ira D. Sankey (1840–1908), accompanying him on many revivals and conducting some of his own. 23 At one revival, he met Leonora Sophia van Marter, a music teacher of Tacoma, Washington, whom he married on October 23, 1895. 24 The earldom passed to Bennet upon his father’s death in late December 1899. 25 Although one of the richest earldoms in England, with 31,500 acres of land and its chief seat Chillingham Castle in Northumberland (famous for its herd of white wild cattle), it also had the highest rent. Consequently, Bennet was constantly in financial straits, residing in the family’s much more modest Thornington House in Northumberland. 26 Known as “The Singing Earl,” he studied under Giovanni Sbriglia (1832–1916), was first president of the Newcastle Symphonium Society, sang at revivals, and participated in concerts until his death. He was also painted miniatures, some of which won awards 27 and were hung in the Royal Academy. 28

No sooner did Crowley agree to a meeting than Bennet entered from the next room. Taking Crowley aside, the Earl spoke to him like a lifelong friend, disclosing intimate details and discussing family secrets with embarrassing frankness. But most remarkable was his claim that his mother and her friend were trying to kill him with magic. He wanted Crowley to protect him. AC viewed him as suffering from “persecution mania.” His predilections for “his old habit of brandy tippling and his newly acquired one of sniffing a solution of cocaine” not only accentuated his concerns—leading Crowley to nickname him the “Earl of Coke and Crankum” 29 —but also explained his presence at Whineray’s shop.

AC saw him as a religious man with a mystical bent, and although he doubted the accuracy of his story, he knew Bennet himself believed it. Therefore, Crowley suggested they take a retirement that spring so the master could teach him magical self defense. The Earl of Tankerville delightedly agreed, and Crowley gained a new student.

George Montagu Bennet (1852–1931), 7th Earl of Tankerville. (photo credit 7.2)

The magicians were coming out of the woodwork: Jones and Fuller, now the Earl of Tankerville. Crowley pondered what could possibly happen next. Then he met Victor Neuburg.

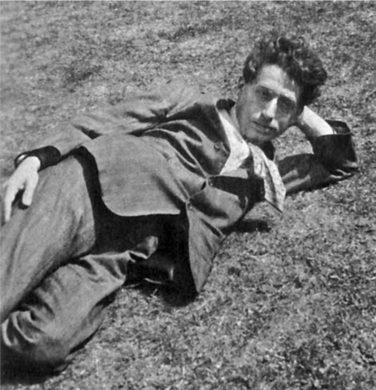

Victor Benjamin Neuburg (1883–1940) was a Jewish poet and native Londoner, born in Islington to Bohemian merchant Carl Neuburg and his wife Jeannette (née Jacobs). 30 Carl left the country shortly after Victor was born, so Jeanette moved in with her mother, Rebecca, where the Jacobs family helped raise Victor. 31 His first published poem, “Vale Jehovah!,” appeared in the October 25, 1903, issue of the Freethinker , which encouraged him to continue publishing regularly, including in The Agnostic Journal . 32 He was a young mystic who believed in reincarnation, vegetarianism, and the existence of a greater reality. Thinking Judeo-Christian religions a sham and finding spiritualism unsatisfying, he was searching for a genuine master.

When he met J. F. C. Fuller in 1906, Neuburg explained that he was studying medieval and modern languages at Trinity College. Fuller remarked on two coincidences: first, he too was a regular contributor to the Agnostic Journal and had admired Neuburg’s writing. Second, his friend—poet and mystic Aleister Crowley—had also attended Trinity. Neuburg was very interested in meeting this friend, and Fuller happily supplied Crowley’s address. Thus he wrote and arranged a meeting.

Crowley stepped into Neuburg’s room and introduced himself. Neuburg was a small man, with a head much too large for his slight body. His lips, Crowley thought, were three times too thick for his face, and he later characterized Neuburg as a “sausage-lipped songster of Steyning.” 33 Despite this, his brown hair and distinguished features made him handsome. Crowley explained that he had read Neuburg’s poetry and was very interested in it because it showed evidence of astral projection. No reply was necessary: Crowley could tell just by looking at him that Neuburg had a terrific capacity for magic. Neuburg confirmed this by stating he had practiced spiritualism and clairvoyance. As the two got to know each other that weekend, they became entranced with each other: Crowley with the apprentice poet and magician, and Neuburg with the older master.

Victor Benjamin Neuburg (1883–1940). (photo credit 7.3)

Despite the dons’ objections, Neuburg invited Crowley to speak at Cambridge on Thursday, February 28, 1907. This “First Missionary Mission,” as AC dubbed it, was one of many visits he would make to Neuburg’s poetry club, the Pan Society, to read poetry, discuss magic, and recruit students into his fold. Neuburg in turn devoted himself to the study of magic.

A formative episode in Crowley’s work occurred when he wrote to Jones on March 7, asking permission to take a vow of silence. Jones discouraged Crowley from using this fourth power of the Sphinx, and suggested an alternative: Crowley ought to vow to answer no questions for a week, punishing each violation of this oath with a razor-cut on the forearm. Crowley picked up the gauntlet. On the first day of his oath, he slipped twenty-four times, but with an equal number of gashes on his arm, he quickly learned. The next day, he slipped only twelve times, the total dwindling down to around seven for the following days. In all, he slipped seventy-two times in a week. The exercise taught Crowley an important lesson in vigilance: not only did it make him carefully measure his words and responses, but it raised his consciousness of the world around him. He was so impressed that he incorporated the lesson into his cannon of magical instructions as “Liber Jugorum.”

Rose, seeing her husband’s forearms covered with scabs and slices, hated the exercise. This friction further eroded their conjugal life and made him fear that she was interfering with the Great Work. With precious little in common, and Rose’s drinking poisoning even that, Crowley moved into rooms on the fourth floor of 60 Jermyn Street, London, on the weekend of March 23–24.

Relieved to be alone, he worked to a peak at the end of May, when he took the oath of a Magister Templi (8°=3°) in the presence of “Tankerville.” In so doing, Crowley vowed to emerge from the Ordeal of the Abyss and stand in the entrance hall to the Third Order as a purely magical entity, selfless and unattached. His task as a Master of the Temple was twofold: First, he had to found a temple (which was just the work he and Jones were doing). In addition, he vowed to interpret every event in his life as a particular dealing of God with his soul. While any person could theoretically take this oath to find the significance behind everything, the consequences for one unprepared for the grade of Magister Templi were terrible indeed; at the very least, it swept an inexperienced soul inexorably toward the Abyss.

The next day, Crowley and Tankerville arranged to take the magical retirement they’d planned since their first meeting. It was the perfect opportunity for both to study and learn. They planned to sail to Marseilles, Morocco, Mongolia, Gibraltar, and Spain, and began the voyage that June. Although Crowley attributed Montagu’s claims of magical attack to paranoia, he taught him a protection technique to alleviate his worries. As Crowley wrote:

Whenever he noticed his mother flying past the moon on her broomstick, he would perform a banishing ritual, and sail out in his astral body onto the word and chop the broomstick like Sigfried with the lance of Wotan, and down she would fall into the Straits of Gibraltar, plop, plop. 34

As they journeyed, Crowley also wrote many of the pieces that would appear in Konx Om Pax: “The Mask of Gilt” (July 12), “There is No Other God than He” (July 13), “Return of Messalina” (July 22), and the piece considered by many to be his best poem, “La Gitana” (July 21). The last is about a Spanish gypsy who made Crowley forget his domestic troubles:

Your hair was full of roses in the dewfall as we danced,

The sorceress enchanting and the paladin entranced,

In the starlight as we wove us in a web of silk and steel

Immemorial as the marble in the halls of Boabdil,

In the pleasaunce of the roses with the fountains and the yews

Where the snowy Sierra soothed us with the breezes and the dews!

Crowley agreed with the critics, noting, “The Morocco poems seem to me about the best I have ever done.” 35

Before long, however, both men got on each other’s nerves. Crowley tired of the Earl’s incessant delusions, writing sarcastically in his journal for July 11, “I don’t know about the Power of Samadhi; but I can tolerate Tankerville, and I want a new grade specially for that .” He summed up his feelings about Bennet in “The Suspicious Earl”:

There was a poor bedevilled Earl

Who saw a Witch in every girl,

A Wehr-Wolf every time one smiled,

A budding Vampire in a child,

A Sorcerer in every man,

A deep-laid Necromantic plan

In every casual word; withal

Cloaked in its black horrific pall

A Vehmgericht obscenely grim,

And all designed—to ruin him! 36

Meanwhile, the earl tired of the master’s constant lessons, telling Crowley, “I’m sick of your teaching, teaching, teaching as if you were God Almighty and I were a poor bloody shit in the street!” Shortly after they returned to Gibraltar on July 20, they had a row and parted. On July 25, they arrived in Southampton aboard the Scharnhorst . 37

Throughout these adventures, Crowley continued to produce poetry. He had already completed in February the poems that made up Clouds without Water . Additional 1907 releases from SPRT included Rosa Coeli, Rosa Inferni , and Rodin in Rime , all of which featured color lithographs of Rodin’s watercolors. The last book was a bold gesture on Crowley’s part because it was fashionable to criticize Rodin at this time; but Crowley chose to defend and praise him instead. SPRT also reissued Tannhäuser and The Mother’s Tragedy .

Finally, the winning essay on the works of Aleister Crowley appeared: The Star in the West , by J. F. C. Fuller, appeared as a prodigious, 328-page volume with white buckram covers gilt-stamped with Crowley’s Magister Templi (8°=3°) emblem, or lamen. A vesica enclosed the lamen, which consisted of a crown with a sword’s blade extending through and far above it, balancing on its tip a scale whose pans held the Greek letters alpha and omega; it also sported five V’s, which represented Crowley’s Magister Templi motto, Vi Veri Vniversum Vivus Vici (“By the power of truth, I have conquered the universe”). Although Crowley and Fuller released only one hundred copies of this signed and numbered edition, 38 it was significant in marking the appearance of Frater V.V.V.V.V., the Magister Templi.

Although Crowley professed not to accept this grade until 1909, he clearly claimed it much sooner: on May 30, 1907, five months after Jones declared him 8°=3°, he took his 8°=3° oath with Montagu as a witness; he published The Star in the West with his Magister Templi lamen on the cover; and his diary from this period contains many references to the attainment, such as “I think this stamps me clearly as an 8°=3° elect.” 39 After returning to London from his trip with Montagu, Crowley mailed out cards which bore the lamen of V.V.V.V.V.; this mailing puzzled at least one recipient, who wrote to the Daily Mirror:

Contemporary cartoon about Crowley’s Magister Templi lamen. (photo credit 7.4)

Two days ago I received the enclosed card anonymously, and just glancing at it briefly, thinking it an advertisement of some sort, I placed it on the mantlepiece.

Within a few minutes, disasters of a minor kind began to happen in my little home.

First, one of my most valuable vases fell to the ground and was smashed to pieces. My little clock stopped—the clock was near the card—and then I discovered to my amazement that my dear little canary lay dead at the bottom of its cage! 40

Although the letter is unsigned, Crowley is likely the author.

Alas, The Star in the West turned out to be the name of a children’s book published in London the previous year. 41 This mix-up caused a chagrined Fuller to publish an apologia that summer in the Athenaeum:

I exceedingly regret that through an unfortunate coincidence my recently published volume The Star in the West , a critical essay upon the writings of Aleister Crowley, bears the same title as a Welsh story for children by Miss Mary Debenham, already published by the National Society. But for the fact that my work was already printed and bound before my attention was drawn to this point, I would willingly have changed the title. However, with the courteous consent of both publishers, the title is retained; and I trust this letter will save booksellers any inconvenience that might have arisen from this similarity of the titles. 42

Unlike Crowley’s postcard, no mishaps were reported with Fuller’s book.

By this time, Crowley was living in London at Coram Street, and new works continued to flow from his busy pen: he followed his poetic adaptation of Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” and hymns to the Virgin Mary with “The Hermit,” and “Empty-headed Athenians.” Next, he worked on Konx Om Pax , writing its prologue and dedication and designing its cover. That fall, Crowley wrote the novella “Ercildoune” and the short story “The Wizard Way.” 43

Volume three of his collected Works was also in press at the time. Although The Book of the Law had been typeset and slated to appear as an appendix with a brief commentary, 44 Crowley scrapped the plan. Instead, the appendix became a bibliography of Crowley’s published works up through 1906, compiled by Duncombe-Jewell. Despite intentional omissions—notably, White Stains and Snowdrops from a Curate’s Garden —the bibliography was excellent and progressive; 45 information on print runs, paper type, and binding clarified to all how fine and collectible Crowley’s first editions were.

Familial tension finally erupted at the end of October, when Crowley received a grocer’s bill for the 120 bottles of liquor that Rose had purchased over the past five months. Pondering where the devil Rose could have stashed a bottle of liquor a day, Crowley searched the house but found no trace of alcohol anywhere. He had to assume she drank it all. Armed with the evidence he needed, Crowley confronted his wife with the facts. She admitted to drinking heavily, and Crowley sent her to Leicester to dry out for two months.

When he first read Sri Brahma Dhàra (“Shower from the Highest”) by yogi Mahatma Sri Agamya Guru Paramahamsa (born c. 1841), 46 Crowley had heard that the fierce author was nicknamed the Tiger Mahatma and that he referred to seekers who were too meek for his tastes as “sheep.” A retired judge, he devoted himself to religion and was described by German philologist and orientalist Max Müller (1823–1900) as the only Indian saint he had ever known. His temper was both fierce and legendary, which seemed to attract—and ultimately repel—his followers. 47 Back on November 13, when the guru was on his second trip to London, Crowley had sent him a cryptic letter. “If you are the one I seek,” the note read, “this will suffice.” He had enclosed his name and address and awaited a reply. A response had come the next day, and several days later Crowley had begun meeting the guru for instructions on yoga.

The “Tiger Mahatma,” Sri Agamya Guru Paramahamsa. (photo credit 7.5)

That was last fall. Now that Agamya had returned to London, Crowley rejoined him and his “tiger cubs” at 60 South Audley. Before long, however, Crowley and Agamya had “a devil of a row” 48 at a meeting of students. In response, AC asked Fuller—who, he knew, was well versed in both yoga and Agamya’s writings (of which he thought little)—to attend a meeting the following Sunday. Fuller went, and his disdain for the proceedings was evident. After ninety minutes’ talk, the yogi grew upset with Fuller, crying out, “You pig-faced man! You dirty fellow, you come here to take away my disciples … Crowley send this pig-one, eh?” At that, Fuller politely took his hat and cane and walked to the door. Before closing it behind himself, Fuller poked his head back in and, in Hindi, replied, “Shut up, you son of a sow!” 49 Fuller could hear the yogi’s characteristic fit of anger as he closed the door and walked away.

Agamya’s concerns may have been well-founded. Crowley, trying to found an order with Jones, sought students, and the same purposefulness that caused Tankerville to exclaim “I’m sick of your teaching, teaching, teaching” may have made Agamya uneasy: the Tiger Mahatma’s claim that AC took away his students may reflect either a concern or the truth.

Crowley’s results with magic began to resemble those he obtained in Cairo in 1904. Crossing the Abyss required that he release everything dear to him: his wife, daughter, and that one item for which he had fought so hard—his holy guardian angel. The lesson, he learned, was not to lose these things but to be able to release them and act without attachment; for, that fall, Crowley realized his holy guardian angel was still with him. “I can, I know, get into touch with Adonai at will,” he recorded in his diary. 50 Adonai was the Hebrew word for “lord,” and was used as a title of the holy guardian angel.

On October 30, Crowley got it in writing. That evening, the automatic writing “Liber VII” was penned, the first of a series of “Holy Books” that Crowley claimed were dictated by his holy guardian angel, Aiwass. In one sitting of two and a half hours, Crowley took down its seven chapters, one for each of the traditional astrological planets; although longer than The Book of the Law , it took thirty fewer minutes to write. “Liber VII,” Crowley explained, was an account of “the voluntary emancipation of a certain Exempt Adept from his Adeptship. These are the birth-words of a Master of the Temple.” 51

Immediately after finishing VII, he began another. Throughout this writing, Crowley basked in the trance of samadhi , his own identity dissolved into the cosmic dance, recording passively the dictation of his inner voice. 52 These writings continued intermittently until November 3, when he finished “Liber Cordis Cincti Serpente,” or “The Book of the Heart Girt about by the Serpent,” the longest of the Thelemic Holy Books. Each of its five chapters (one for each element) contains sixty-five verses describing the relationship of an Adeptus Minor (5°=6°) with his holy guardian angel.

Ever since Kangchenjunga, Crowley and Jones met regularly to discuss, compare and practice magic. They knew they held the key to a newer and more potent formula of initiation than that of old, and this led Crowley to write:

O restless rats that gnaw the bones

Of Aristophanes and Paul!

Come up to me and Mr. Jones

And see the rapture of it all! 53

For the past year, however, their lack of a third member to form a governing triad had stalled their formation of a magical order.

On November 15, Crowley visited Jones with a solution: his bright friend, Frater Per Ardua ad Astra (“To the stars through great effort”), also known as Frater Non Sine Fulmine (“Not without thunder”), known among mundane men as Captain J. F. C. Fuller, would be the third. Jones considered the proposition and consented to forming the triad.

The A A

A , commonly known as the Argenteum Astrum or Silver Star, successor to the GD, was born.

, commonly known as the Argenteum Astrum or Silver Star, successor to the GD, was born.

Through the remainder of that year, automatic writings continued to pour from Crowley’s pen. On November 25 he wrote “Liber LXVI,” or “Stellae Rubae.” Its contents are cryptically described as “a secret ritual of Apep, the Heart of IAO-OAI, delivered unto V.V.V.V.V. for his use in a certain matter of Liber Legis.” 54 The veiled passages of this writing become clear when they are understood to describe a sexual ritual with his current mistress, a golden-haired, green-eyed woman by the name of Ada Leverson. Her name appears as an acronym of the first two lines:

Apep deifieth Asar.

Let excellent virgins evoke rejoicing, son of Night! …

There shall be a fair altar in the midst, extended upon a black stone. At the head of the altar gold, and twin images in green of the Master. In the midst a cup of green wine. At the foot the Star of Ruby. The altar shall be entirely bare.

And so on. She is alo “the gilded lily with geranium lips” in Crowley’s short story, “Illusion d’Amoureux,” which opens with the description:

Kindlier than the moon, her body glowed with more than harvest gold. Fierier than the portent of a double Venus, her green eyes shot forth utmost flames. From the golden chalice of love arose a perfume terrible and beautiful, a perfume strong and deadly to overcome the subtler fragrance of her whole being with its dominant, unshamed appeal. 55

Ada Esther Leverson, née Beddington (1862–1933), a dozen and one years older than Crowley, was an attractive author whose first novel, The Twelfth Hour , Grant Richards had published that year (1907). Although she had known all the important literary people since the 1880s, she made no attempt to write until Oscar Wilde—who dubbed her “The Sphinx” for her “strange, enigmatic expression”—suggested in 1892 that she contribute to the magazines Black and White and Punch . She did and by 1903 had a regular column, “White and Gold,” in the Referee . She had married young and hastily—at age nineteen, she married Ernest David Leverson (c. 1851–1921), an East Indian merchant eleven years her senior, at Marylebone. 56 She had a daughter, Violet, around 1890, but nevertheless found marriage dissatisfying. 57 Finding divorce too scandalous, she simply split with her husband and carried on affairs with William Ulick O’Connor Cuffe the fourth Earl of Desart, Prince Henri d’Orléans, and George Moore. “To marry at Hastings would be to repent at St. Leonard’s,” she often joked, and Crowley had to agree with another of Wilde’s characterizations: she was the wittiest person he had ever met. 58 Reviewing her works, Crowley called her “easily the daintiest and wittiest of our younger feminine writers.” 59 However, neither left much record of the affair; it appears to have been a brief and convenient tryst for them both. 60 Crowley followed Wilde in carrying on her nickname, dedicating to her the sensuous poem “The Sphinx” in The Winged Beetle (1910).

Ada Leverson (1862–1933). (photo credit 7.6)

On December 3, Crowley scribbled down a series of sigils representing the genii of the twenty-two paths of the reverse side of the Tree of Life—the World of Shells known as the Qlippoth—and the genii of the twenty-two paths of the kabbalah, corresponding to the twenty-two major cards of the tarot. This continued to December 5 and 6, when he received twenty-two verses describing “the cosmic process so far as it is indicated by the Tarot Trumps.” 61 He also received the names of the genii whose sigils he recorded several days previously. This constituted “Liber Arcanorum,” one of the more puzzling and inaccessible of the Holy Books, which, some believe, holds the key to a grimoire of magic dealing with the reverse side of the Tree of Life.

On December 8, Crowley took a break from being Aiwass’s scribe and returned to Cambridge despite official protestations. This time he met Norman Mudd (1889–1934) of Manchester, the bright son of a poor certified schoolmaster, William Dale Mudd (b. 1861) and his wife Emma (born c. 1860). 62

Born in Prestwich, Lancashire, Norman was the middle of three children, his other siblings being older sister Nellie (b. 1887) and younger sister Era (born c. 1894). 63 Norman attended Ducie Avenue Schools, 64 earned a mathematics scholarship to Cambridge, and had just entered Trinity that July. Physically short and unattractive, he introduced himself with his meek trademark statement, “You won’t remember me. My name’s Mudd.” His intellect, however, was as virile as any: a Freethinker, he was a friend of Neuburg’s and belonged to his Pan Society. He and Crowley spent hours talking. As Mudd recalled, “I then understood for the first time what life was or might be; and the spark of that understanding has been in me ever since, apparently unquenchable, always working.” 65 Captivated by the magician, Mudd felt that magic was the only thing he had encountered that gave his life any meaning or value, and he gladly agreed to distribute Crowley’s books on campus.

The automatic writing “Liber Porta Lucis, Sub Figura X” (“The Book of the Gate of Light”) followed on December 11 and 12. Its brief text described how the Masters sent forth Frater V.V.V.V.V. as their messenger, giving their message and exhorting men to take up the Great Work. In short, it was an invitation to the A A

A . The number of this book, ten, was that of Malkuth, the sphere on the Tree of Life where the initiate symbolically begins.

. The number of this book, ten, was that of Malkuth, the sphere on the Tree of Life where the initiate symbolically begins.

“Liber Tau” followed the next day. The book divided the Hebrew alphabet into seven triads that represented “ideas relating respectively to the Three Orders comprised in the A A

A .”

66

Its number, four hundred, is that of the Hebrew letter Tau, under which the remaining twenty-one letters are subsumed.

.”

66

Its number, four hundred, is that of the Hebrew letter Tau, under which the remaining twenty-one letters are subsumed.

Later that day, he penned “Liber Trigrammaton” (XXVII). This book synthesized the Chinese duality of yin-yang (represented by the solid and broken lines of the I Ching) with the Tao (represented in this system by a dot). The result was twenty-seven trigrams and their corresponding text. Crowley equated this book with the Stanzas of Dzyan, upon which The Secret Doctrine , the cornerstone of Blavatsky’s Theosophical movement, was a comment.

Finally that winter, Crowley received “Liber DCCCXIII vel Ararita.” Its seven chapters described “a very secret process of initiation” 67 whereby any idea is reduced to unity by synthesis, then drawn beyond by the method itself.

The significance of these texts—from Stellae Rubae to Ararita—is that Crowley would ultimately place them in the same category as The Book of the Law: immutable revealed texts transmitted through him by a higher intelligence. Crowley would eventually devote time to explaining the contents of some of these books; 68 however, the meaning of others remains unclear to this day. Regardless, they represented an important spiritual advancement. On December 15, he wrote in his diary, “not since my attainment in October has there been any falling away whatever. I am able to do automatic writing at will … I cannot doubt that I am an 8°=3° … At last I’ve got to a stage where desire has utterly failed; I want nothing.”

The time to advertise the A A

A came at the beginning of 1908. To this end, Crowley commissioned Walter Scott to print five hundred copies of Konx Om Pax

for SPRT. The book was one of Crowley’s more enigmatic offerings, ranking up there with The Sword of Song

for its stupefication value. Its title derived from a phrase used in Greek mystery religions; heated debate has long surrounded its meaning, but the GD equated it with the Egyptian Khabs Am Pekht

, “light in extension.” Illumination. Hence, Crowley subtitled the book “Essays in Light.” Adding even more mystery, the black cover sported a curious design that careful investigation revealed was the title, stretched long and thin across the entire front cover so that it was nearly illegible. The book opened with quotes—in their original languages—from various religious and philosophical sources, including the Qur’an, Gnostic texts, Tao Teh King (Tao Te Ching), and the Stele of Ankh-f-n-Khonsu. The dedication left no doubt that Crowley was writing for a mystical society:

came at the beginning of 1908. To this end, Crowley commissioned Walter Scott to print five hundred copies of Konx Om Pax

for SPRT. The book was one of Crowley’s more enigmatic offerings, ranking up there with The Sword of Song

for its stupefication value. Its title derived from a phrase used in Greek mystery religions; heated debate has long surrounded its meaning, but the GD equated it with the Egyptian Khabs Am Pekht

, “light in extension.” Illumination. Hence, Crowley subtitled the book “Essays in Light.” Adding even more mystery, the black cover sported a curious design that careful investigation revealed was the title, stretched long and thin across the entire front cover so that it was nearly illegible. The book opened with quotes—in their original languages—from various religious and philosophical sources, including the Qur’an, Gnostic texts, Tao Teh King (Tao Te Ching), and the Stele of Ankh-f-n-Khonsu. The dedication left no doubt that Crowley was writing for a mystical society:

To all and every person in the whole world who is without the Pale of the Order; and even to Initiates who are not in possession of the Password for the time being … 69

The text itself was a mixed bag of essays: “The Wake World” was an allegorical account of initiation, using the symbolism of kabbalah and the tarot. The skit “Ali Sloper, or the 40 Liars” parodied several GD members, himself, and a yuletide argument between Bowley and Bones (Crowley and Jones) on the nature of truth. The philosophical essay “Thien Tao” followed, and “The Stone of the Philosophers,” a collection of poems written during his association with Tankerville, concluded the volume.

Although the book is truly clever and witty, it bombed like a joke that needed explaining. The Scotsman considered it “more tolerable in its verse than its prose, for a poet is not expected to be sensible.” Ironically, a reviewer for John Bull —which would make Crowley’s destruction its personal crusade only three years later—was among the few to see its humor: “I was moved to so much laughter that I barely escaped a convulsion.” 70 Perhaps the most critical review came from Mathers, who, objecting to its description of him as a thief, sicced his solicitors, Messrs. Nussey and Fellowes, on the author. Crowley replied simply, “I care as little for your threats of legal action as for your client’s threats of assassination … I am surprised that a firm of your standing should consent to act for a scoundrel.” 71