His faith in the Secret Chiefs and their message renewed, Crowley returned to London with his students and took a flat at 124 Victoria Street as the offices of The Equinox . He decorated the rooms with red curtains, a stuffed crocodile, and several Buddhas, then began work on the second issue. It appeared on the autumnal equinox, September 20, 1909, with a colorful assortment of articles: Crowley contributed an essay on the psychology of hashish as “Oliver Haddo,” his fictitious counterpart in Maugham’s The Magician . Lord Dunsany (1878–1957) offered the short story “A Sphinx at Gizeh,” 1 Neuburg “The Lost Shepherd,” Crowley’s Cambridge follower G. H. S. Pinsent 2 “The Organ in King’s Chapel, Cambridge,” Allan Bennett “A Note on Genesis,” and George Raffalovich “The Man-Cover.” Spare provided illustrations for the article “A Handbook of Geomancy.” Most significantly, Fuller, under Crowley’s supervision, contributed the second installment of “The Temple of Solomon the King.” This chapter recounted Crowley’s initiation into the GD, reproducing every one of its First Order rituals. Crowley believed the Secret Chiefs had released him from his vow of secrecy; as The Book of the Law put it: “Behold! the rituals of the old time are black.” 3 By publishing these secrets, he dissipated their power in favor of the new order.

The Veil of Isis was lifted, and the whole world looked on the undergarments of the GD. Crowley promised to remove even these in the next issue, which would contain the remainder of the GD corpus.

Meanwhile, Clouds without Water appeared under the pseudonym of Reverend C. Verey. The book is a farce, supposedly edited from a private manuscript to reveal the horrors to which Satan can drive lost sheep. Its preface contains the odd semibiographical lines, “the wife of the man, driven to drink and prostitution by the inhuman cruelty of his mistress,” paralleling Crowley’s personal problems. Poetry formed the bulk of the text, with ridiculously pious end notes on its content (“only a Latin dictionary can unveil the loathsome horror” of the word “fellatrix”). It closes with a prayer for redemption.

While many of the poems grew out of his affair with Lola (Vera Bentrovata), Crowley loses sight of her part way through and recalls Rodin’s student, sculptress Kathleen Bruce. Poems V, VI, and VII are for her, and her name even appears as an acrostic in the opening “Terzain”:

King of myself, I labour to espouse

An equal soul. Alas! how frail I find

The golden light within the gilded house.

Helpless and passionate, and weak of mind!

Lechers and lepers!—all as ivy cling,

Emasculate the healthy bole they haunt.

Eternity is pregnant; I shall sing

Now—by my power—a spirit grave and gaunt

Brilliant and selfish, hard and hot, to flaunt

Reared like a flame across the lampless west,

Until by love or laughter we enchaunt,

Compel ye to Kithairon’s thorny crest—

Evoe! Iacche! consummatum est.

Her new husband, explorer Robert Scott, was reportedly furious to find his wife’s name in this bizarre book.

The sharp division between Crowley’s private and magical lives was more pronounced than ever. Although magic proceeded well, he nevertheless spent much of that summer in the Thames valley, brooding over his forthcoming divorce. As he put it, “My soul was badly bruised by the ruin of my romance.” 4 Seeking solace in his childhood nostalgia for weirs, Crowley spent time late that summer in a canoe on Boulter’s Lock, Maidenhead, on the Thames thirty miles west of London. There, in a sixty-hour marathon session, he wrote his classic mystic poem, “Aha!” In the form of a dialogue between the teacher Marsyas (Crowley) and his pupil Olympas (any seeker), it describes the many mystical states he had experienced along the path to becoming a Master of the Temple, including the subjects of equilibrium, the veil of matter (paroketh) , the knowledge and conversation of the holy guardian angel, the vision of the universal peacock (atmadarshana) , the ordeal of the Abyss, the vanity of speech, the destruction of the ego, and the bliss of transcendence (ananda) . In particular, his discussion of the ordeal of the Abyss poignantly mirrors the heartache he was feeling as he penned these verses:

MARSYAS. Easy to say. To abandon all,

All must be first loved and possessed.

Nor thou nor I have burst the thrall.

All—as I offered half in jest,

Sceptic—was torn away from me.

Not without pain! THEY slew my child, Dragged my wife down to infamy

Loathlier than death, drove to the wild

My tortured body, stripped me of

Wealth, health, youth, beauty, ardour, love.

Thou hast abandoned all? Then try

A speck of dust within the !eye!

With his divorce pending, Crowley was vividly aware of the demands of the path he had chosen: he had thrown away his family and fortune to lead the life of a magician. “Aha!” stands not only as autobiography, but as a manual of spiritual attainment.

As the date of his divorce approached, Crowley grew increasingly miserable. If the event itself wasn’t bad enough, Rose was now seeking forgiveness and a second chance. He had managed to refuse so far, but knew he would eventually break down if she persisted. Thus he left town until the whole unpleasant business was over.

On November 10, 1909, Crowley and Neuburg left London for a walking vacation in Algeria. They arrived in Algiers a week later, purchased provisions, and headed south with no plan other than to rough it a few days in a new place. They camped in the open for two nights and slept in a primitive hotel a third before arriving at Aumale, about sixty miles southeast of Algiers, on November 21. The place felt right, so they bought notebooks and settled in.

Going through his rucksack, Crowley examined the papers he had brought on Enochian magic. He planned to publish them in a future Equinox , but they now held a greater usefulness for him. Recalling his abortive attempts at doing the Thirty Calls during his visit to Mexico nine years ago, he realized a lot had changed since 1900. He was a Master of the Temple now. Perhaps the barriers that once blocked the 28th Aethyr from him would now yield.

After dinner on November 23, Crowley and Neuburg found a secluded place in the desert. AC removed his scarlet calvary cross inset with a huge topaz. He gazed into the stone while concentrating on his third eye, the ajna chakra , and when he felt prepared to receive a vision, he began the 28th Call in the Angelic Language: “Madariatza das perifa BAG cahisa micaolazoda saanire caosago od fifisa balzodizodarasa Iaida.” In English, it meant, “The heavens that dwell in the 28th Aire are mighty in the Parts of the Earth, and execute the judgement of the Highest!” Completing the conjuration, he gazed into the topaz and described what he saw and the words that came to him. Neuburg, with pen and notebook, recorded what followed:

There cometh an Angel into the stone with opalescent shining garments like a wheel of fire on every side of him, and in his hand is a long flail of scarlet lightning; his face is black, and his eyes white without any pupil or iris. The face is very terrible indeed to look upon. Now in front of him is a wheel, with many spokes, and many tyres; it is like a fence in front of him.

And he cries: O man, who art thou that wouldst penetrate the Mystery? for it is hidden unto the End of Time. 5

And so it began. The entire vision lasted an hour.

The Edinburgh courtroom came to order on November 24 to hear the uncontested complaint of Rose Edith Crowley (formerly Skerrett, née Kelly) against her husband, Edward Alexander Crowley, a.k.a. Lord Boleskine and Count MacGregor. Lord Edward Theodore Salvesen (1857–1942) 6 listened carefully from the bench as the thirty-five-year-old pursuer gave her testimony, from her 1897 marriage, her elopement six years later, the birth of their first daughter, her abandonment in China, and the death of their child. Mr. Jameson, who questioned Rose, asked, “When you met the defendant, was he then calling himself Aleister Crowley?”

She shook her head. “No, he was then Count Svareff. I knew, however, his real name was Edward Alexander Crowley. Later he called himself MacGregor in order to identify himself with Scotland. That’s the name he used on our marriage certificate, although he gave his father’s name as Edward Crowley. Shortly after we were wed, he began using the name Lord Boleskine. He said it was because Scots took the names of their property.”

“I take it he is a little eccentric?”

“Oh, yes!”

The damning evidence came when she described her complaint against Crowley. That summer, on July 21, she left him and took a house on Warwick Road because he had been beating her. Two weeks later, according to testimony from Mrs. Dauby the charwoman (whom Crowley had called a drunken ex-prostitute), Master Crowley had a woman with him: he had asked Dauby to bring them tea in the library that evening, and again in the morning. Throughout the night, she heard laughter coming from the room. If that weren’t scandalous enough, the chauffeur, Charles Randle, testified that Crowley had fathered a child by a friend of his. When Gerald Kelly took the stand, he confessed that, although he was Crowley’s friend, he knew little about his background. AC, he said, purchased Boleskine for far more than its worth; the manor had a lot of land, but most of it was perpendicular. Crowley, he said, was very stupid about money.

“You said he is a writer,” Salvesen posited. “Does he make anything by it?”

Gerald snorted. “Certainly not.”

Salvesen considered the case, granted Rose her divorce, and awarded her custody of Lola Zaza, with £1 a week as alimony. Since Crowley had spent his fortune on publishing and mountaineering adventures, he had no money to offer as a settlement, but with the help of Dennes & Co., he set up a trust fund into which would be deposited the £4,000 he would receive when his mother died; these funds would be divided between Crowley and Lola at the discretion of the trustees, Jones and Eckenstein.

Looking at Crowley’s photograph, the judge sat back and mused. “He looks as if he belonged to the stage.”

Jameson said, “He is a literary character, sir. He rather affects the artistic.” 7

The Crowley family—Rose, Lola Zaza, and Aleister—taken shortly after the divorce. (photo credit 9.1)

In retrospect, their marriage was flawed even before alcohol became an issue. Admittedly, Rose’s love inspired passionate songs from the poet, just as Lilith’s death devastated him and the collapse of their marriage depressed him. And although comparatively uneducated and undisciplined, she was a valuable magical partner, leading AC to The Book of the Law , participating in his rituals, and scrying for his friends. Nevertheless, AC placed her third in his life, after books and magic. They shared little in common: he was a writer, she uninterested in literature. Moreover, they spent little time together: shortly after their marriage, he went on his expedition to Kangchenjunga; left her again in China to travel to America; went on a cruise with Tankerville; and maintained separate residences in London and Paris. In the end, theirs appears to have been a marriage held together by little more than the romance of their elopement.

While the divorce unfolded, Crowley and Neuburg headed out of Aumale into the heart of Algeria. Crowley wore a robe and turban and read from the Qur’an as they marched across the desert. Neuburg’s head was shaved except for two tufts of hair that he twisted into horns. Thus Crowley led his familiar djinn about on a chain, to the amazement of the locals.

That evening, they reached Sidi Aissa and, at 8 p.m., performed the 27th Call. From there, they proceeded to Bou Sâada, where they spent most of their trip. It was a quaint little town with houses gathered upon a hill in the middle of the desert. A stream ran through the land below, framed with palms, cacti, orchards, and gardens.

As they regressed through the Thirty Aethyrs over the course of the next month, Crowley and Neuburg recorded the visions—apocalyptic, passionate, and inspired—which they experienced. AC encountered angels, streams of fire, dragons, ringing bells, and a landscape of knives. When they evoked the 21st Aethyr on November 29, Crowley faced an invisible entity that spoke by rapidly placing tastes into Crowley’s mouth: salt, honey, sugar, asafoetida, bitumen, honey. As they progressed, Crowley understood the images to unify every system of magical attainment.

The Calls also initiated him into greater and greater mysteries. In the 15th Aethyr (December 3), a group of Adepts examined Frater Perdurabo at their Sabbath. The first one thrust a dagger into Crowley’s heart, tasted his blood, and spoke the Greek word katharos , thus deeming him at least an Adeptus Minor (5°=6°); indeed, he had received this initiation in 1900 from Mathers himself in Paris. The second, testing the muscles of his right shoulder and arm, pronounced the Latin word fortis , signifying he was an Adeptus Major (6°=5°). The third, examining his skin and tasting the sweat of his left arm, uttered the Enochian word TAN , declaring him Adeptus Exemptus (7°=4°), an exempt adept at the top of the Second Order’s hierarchy. The fourth, examining his neck, said nothing, then opened the right half of his brain and pronounced the Sanskrit samajh . He had crossed the abyss and was a Magister Templi (8°=3°).

A fifth Adept approached, examined the left half of Crowley’s brain, pondered his evidence, and stiffened. He raised his hand in protest and, in his language, declared Crowley was not yet a Magus, 9°=2°: “In the thick of darkness the seed awaiteth spring.” AC still belonged to the first of the three grades of the third and highest order, the Silver Star.

This vision occurred between 9:15 and 11:10 in the morning. Later that afternoon, the magicians climbed the mountain Dáleh Addin in the desert and, at 2:50, attempted to obtain a vision of the 14th Aethyr, named UTI in Enochian. As he proceeded, Crowley encountered thick veils of darkness. Tearing his way through the veils, trying to penetrate their mystery, the darkness was endless. Finally, a voice instructed him, “Depart! For thou must invoke me only in the darkness. Therein will I appear, and reveal unto thee the Mystery of UTI . For the Mystery thereof is great and terrible. And it shall not be spoken in sight of the sun.”

At 3:15, Crowley abandoned the vision.

Descending the mountain, inspiration seized Crowley. He suggested they gather rocks and build a stone circle around a rough stone altar dedicated to Pan. This they did, and wrote magical words of power in the sand. With the temple established, they now needed to worship the deity. A sacrifice was customary, but Crowley had no animal with him. He knew, however, that sacrifices often symbolized the sex act, the spilling of the seed of life. So upon the makeshift altar, beneath the desert sun, Victor assumed the active role in an act of anal sex with his master.

Crowley staggered back to Bou Sâada in a drunken state of spiritual ecstasy and collapsed on his bed, feeling insights he had never known before. In his own words, the ritual “produced a great wonder,” for he realized for the first time what power could be wielded by using sex in ritual. He also accepted the homosexual component of his sexuality; this stood in sharp contrast to his college relationship with Pollitt, which ended with bitterness and recriminations. The indulgence and transcendence of the last taboo that Victorian-Christian mores had programmed into him completely obliterated “Aleister Crowley” and erased his ego. As he wrote:

It was a repetition of my experience of 1905, but far more actual. I did not merely admit that I did not exist, and that all my ideas were illusions, inane and insane. I felt these facts as facts. It was the difference between book knowledge and experience.… All things were alike as shadows sweeping across the still surface of a lake—their images had no meaning for the water, no power to stir its silence. 8

Through the Enochian Calls, Crowley was reliving all the initiations he had experienced: up to this point, he had had sporadic enlightenments that gave him claim to the exalted grades of the A A

A , but now he was systematically and formally going through his initiations.

, but now he was systematically and formally going through his initiations.

For Victor, that day marked the consummation of a love that had grown steadily within him, and which would never in his life find equal.

At 9:50 that evening, they again tried the Call of the 14th Aethyr. This time the consciousness that had been Crowley penetrated the veil, encountered the angel, and by 11:15 was confirmed as one of the masters.

The remaining visions instructed him in what lay ahead. The 13th Aethyr described the work undertaken by a Master of the Temple (8°=3°). The 12th described the City of the Pyramids, the allegorical name for the third sephira, Binah , on the Tree of Life, which represents the 8°=3° grade. Having been fully instructed on the Grade of the Magister Templi and having had his lease in the City of Pyramids approved, he could now move in. All he had to do was ritually recross the Abyss. Staring into the dark wind-swept void, Crowley beseeched his holy guardian angel, “Is there not one appointed as a warden?”

Aiwass replied with the torment-spawned last words of Jesus, “Eloi, Eloi, lama sabacthani.” 9

Returning from the 11th Aethyr, Crowley knew he was alone. Just as he had trodden upon mountains where no one had previously set foot, there was no other person living in the areas he now ventured.

“Accursed” was John Dee’s word for the 10th Aethyr. Its path crossed the Abyss, but Choronzon, the demon of dispersion, guarded the higher grades from those unprepared. Edward Kelly called him “that mighty devil,” the first and deadliest of all evil powers. Crowley and Neuburg knew they needed to be prepared to encounter this infernal entity.

On December 6, the magicians wandered until they found a suitable spot in a desert valley filled with white sand. Sparing no precaution, they gathered stones and arranged them in a huge circle. Around it they traced the protective kabbalistic names of God in the sand: Yahweh, Shaddai El Chai , and ARARITA . Due east of the circle, they inscribed a triangle which enclosed the name Choronzon. To fortify it, they wrote on each of its sides a sacred name as advised in the Goetia: ANAPHAXETON, ANAPHANETON, and PRIMEUMATON. At its vertices they put a pair of letters from the name of MI-CA-EL, the archangel bearing the fiery sword. Into this space they would summon the demon. And in this same space Crowley, robed in black, would scry. Neuburg sat in the fortified circle; his duties were to use his consecrated dagger to command and contain Choronzon in the Triangle of the Art, and to record the content of the vision in his notebook. So grave and serious was this responsibility that he swore an oath:

I, Omnia Vincam, a Probationer of A A

A , hereby solemnly promise upon my magical honour, and swear by Adonai the angel that guardeth me, that I will defend this magic circle of Art with thoughts and words and deeds. I promise to threaten with the Dagger to command back into the triangle the spirit incontinent, if he should strive to escape from it; and to strike with a Dagger at anything that may seek to enter this Circle, were it in appearance the body of the Seer himself. And I will be exceeding wary, armed against force and cunning; and I will preserve with my life the inviolability of this circle, Amen. And I summon mine Holy Guardian Angel to witness this mine oath, the which if I break, may I perish, forsaken of Him. Amen and Amen.

10

, hereby solemnly promise upon my magical honour, and swear by Adonai the angel that guardeth me, that I will defend this magic circle of Art with thoughts and words and deeds. I promise to threaten with the Dagger to command back into the triangle the spirit incontinent, if he should strive to escape from it; and to strike with a Dagger at anything that may seek to enter this Circle, were it in appearance the body of the Seer himself. And I will be exceeding wary, armed against force and cunning; and I will preserve with my life the inviolability of this circle, Amen. And I summon mine Holy Guardian Angel to witness this mine oath, the which if I break, may I perish, forsaken of Him. Amen and Amen.

10

Crowley performed banishing rituals of both the pentagram and hexagram, purging their workplace of both elemental and planetary forces. Then, calling on the sacred names of God, he recited the exorcism of Honorius:

O Lord, deliver me from hell’s great fear and gloom!

Loose thou my spirit from the larvae of the tomb!

I seek them in their dread abodes without affright:

On them will I impose my will, the law of light.…

Their faces and their shapes are terrible and strange.

These devils by my might to angels I will change.

These nameless horrors I address without affright:

On them will I impose my will, the law of light.

These are the phantoms pale of mine astonished view,

Yet none but I their blasted beauty can renew:

For to the abyss of hell I plunge without affright:

On them will I impose my will, the law of light. 11

Traditionally, blood sacrifices helped provide the life essence a spirit needed to materialize. In order to assure a clear encounter with the guardian of the Abyss, he slit the throat of a pigeon at each vertex of the triangle and allowed its blood to drain out, all the while being careful that every drop stayed within the triangle lest its barriers be breached. Sacrifice was a practice as old as the Hindu, Jewish, and Greek religions, and this one represented one of the few he would make in his lifetime. 12 Once the blood soaked completely into the sand, Crowley squatted in the thunderbolt asana and recited the Call of the 10th Aethyr, called ZAX .

The vision began with a deep, chilling voice crying aloud, “Zazas, Zazas, Nasatanada Zazas.” According to tradition, Adam once opened the gates of hell with these words. This time, Choronzon entered their midst.

“I am the Master of Form,” the demon declared, “and from me all forms proceed. I am I. I have shut myself up from the spendthrifts, my gold is safe in my treasure-chamber, and I have made every living thing my concubine, and none shall touch them, save only I. From me come leprosy and pox and plague and cancer and cholera and the falling sickness. Ah! I will reach up to the knees of the Most High, and tear his phallus with my teeth, and I will bray his testicles in a mortar, and make poison thereof, to slay the sons of men.”

Next, Neuburg heard Crowley say, “I don’t think I can get any more; I think that’s all there is.” He was not fooled. Choronzon was mimicking his master’s voice.

Suddenly, Euphemia Lamb appeared before him, tempting and inviting him to make love to her. Neuburg shook his head, attempting to dispel the hallucination. This was another of Choronzon’s tricks, an attempt to lure him out of the protective circle. Neuburg refused to comply. In the face of hideous, loud laughter that echoed wildly about the valley, Neuburg commanded him to proceed with the vision.

“They have called me the God of laughter, and I laugh when I will slay. And they have thought that I could not smile, but I smile upon whom I would seduce, O inviolable one, that canst not be tempted.” With that, Choronzon slipped in an appeal to Neuburg’s pride and vanity: “I bow myself humbly before the great and terrible names whereby thou hast conjured and constrained me. Let me come and put my head beneath thy feet, that I may serve thee. For if thou commandest me to obedience in the Holy names, I cannot swerve therefrom. Bid me therefore come unto thee upon my hands and knees that I may adore thee, and partake of thy forgiveness.”

“Back, demon!” Neuburg commanded. “And continue with the vision!”

He did. “Choronzon hath no form, because he is the maker of all form; and so rapidly he changeth from one to the other as he may best think fit to seduce those whom he hateth, the servants of the Most High. Thus taketh he the form of a beautiful woman.” And so he did. “Or of a wise and holy man.” He did so again. “Or of a serpent that writheth upon the earth ready to sting.” And again. Then, shifting gears, Choronzon interrupted his dialogue with a request: “The sun burns him as he writhes naked upon the sands of hell so that he is sore athirst. Give unto me, I pray thee, one drop of water from the pure springs of Paradise, that I may quench my thirst.”

Neuburg held his post and offered no water. “Continue with the vision!”

Next, Crowley’s voice came from the triangle. “Sprinkle water on my head. I can hardly go on!”

Again calling upon the names of god, Neuburg commanded the uncooperative spirit to continue. He hedged, and Victor cursed him with the names and the pentagram. Undaunted, Choronzon simply roared back at the Neophyte. “I feed upon the names of the Most High. I churn them in my jaws, and I void them from my fundament. I fear not the power of the Pentagram, for I am the Master of the Triangle. Be vigilant, therefore, for I warn thee that I am about to deceive thee. I shall say words that thou wilt take to be the cry of the Aethyr, and thou wilt write them down, thinking them to be great secrets of Magick power, and they will be only my jesting with thee.”

His was an unsettling declaration, as one of the basic assumptions of magic was that the true names of God compelled all spirits. But this chaotic entity that they had called forth openly defied these laws. Shaken, Victor commanded, “In the name of Aiwass, continue!”

The demon quickly shot back, “I know the name of the Angel of thee and thy brother Perdurabo. All thy dealings with him are but a cloak for thy filthy sorceries.”

Neuburg replied indignantly to that remark, “I know more than you, foul demon, and I do not fear you. I command you to proceed.”

“Thou canst tell me naught that I know not, for in me is all Knowledge: Knowledge is my name.”

“I tell you, proceed!”

“Know thou that there is no Cry in the tenth Aethyr like unto the other Cries, for Choronzon is Dispersion, and cannot fix his mind upon any one thing for any length of time. Thou canst master him in argument, O talkative one; thou wast commanded, wast thou, not to talk to Choronzon? He sought not to enter the circle, or to leave the triangle, yet thou didst prate of all these things. Woe, woe, woe, threefold to him that is led away by talk, O talkative One.”

“I warn you, you anger me. Unless you wish to feel the pain of hell, continue.”

Again Choronzon retorted, “Thinkest thou, O fool, that there is any anger and any pain that I am not, or any hell but this my spirit?” Next, he sprang into a dialogue about Crowley’s stupidity. “O thou that hast written two-and-thirty books of Wisdom, and art more stupid than an owl, by thine own talk is thy vigilance wearied, and by my talk art thou befooled and tricked, O thou that sayest that thou shalt endure. Knowest thou how nigh thou art to destruction? I heard it said that Perdurabo could both will and know, and might learn at length to dare, but that to keep silence he should never learn.”

His words came quicker and quicker. Neuburg, concentrating on his note book, scribbled frantically to keep up. With the magician suitably distracted, Choronzon tossed sand on the circle, trying to fill it in as he rambled. Then, running out of things to say, the demon began reciting “Tom o’ Bedlam.”

Neuburg may have realized in that moment that Choronzon was up to no good, but it was far too late. The demon sprang over the hole in the circle and threw Neuburg hard to the ground. They struggled and rolled in the sand. Choronzon, in the form of a naked savage, tried to tear out Neuburg’s throat and bite through the bones of his neck with his frothing fangs. Neuburg, meanwhile, reached desperately for his dagger. Fingers closing around the hilt of the magical weapon, Neuburg struck with the blade and called on the holy four-lettered name of God, commanding Choronzon back to the triangle.

And he obeyed.

Neuburg repaired the breech in the circle, and the demon continued, “All is dispersion. These are the qualities of things. The tenth Aethyr is the world of adjectives, and there is no substance therein.”

The demon resumed the form of Lamb and again tempted Neuburg to no avail. Then he complained he was cold and asked permission to leave the triangle in order to find something to cover his nakedness. Neuburg refused, and again threatened Choronzon with retribution if he did not proceed.

So he did. “I am commanded, why I know not, by him that speaketh. Were it thou, thou little fool, I would tear thee limb from limb. I would bite off thine ears and nose before I began with thee. I would take thy guts for fiddle-strings at the Black Sabbath.” Then, taunting, “Thou didst make a great fight there in the circle; thou art a goodly warrior!”

“You cannot harm one hair of my head,” Victor stood firm.

He roared, “I will pull out every hair of thy head! Every hair of thy body, every hair of thy soul, one by one.”

“You have no power.”

“Yea, verily, I have power over thee, for thou hast taken the Oath, and art bound unto the White Brothers, and therefore have I the power to torture thee so long as thou shalt be.”

“You lie.”

“Ask of thy brother Perdurabo, and he shall tell thee if I lie!”

“No. It is no concern of yours.”

At that, Choronzon taunted Neuburg, trying to convince him that magic was all gibberish, that the names of power were, in fact, powerless. Realizing that all would be lost if he doubted for even an instant, Neuburg kept the demon at bay.

Choronzon continued, “In this Aethyr is neither beginning nor end, for it is all hotch-potch, because it is of the wicked on earth, and the damned in hell. And so long as it be hotch-potch, it mattereth little what may be written by the sea-green incorruptible Scribe. The horror of it will be given in another place and time, and through another Seer, and that Seer shall be slain as a result of his revealing.” 13

With that prophecy, the demon disappeared. Crowley knew he was gone. He removed his magical ring and, with it, wrote the name BABALON in the sand. Two hours after beginning, the vision was over. Together, Crowley and Neuburg destroyed the circle and triangle, scattering the rocks about. They lit a bonfire to purify the valley of the unholy power they had called to earth, and counted themselves lucky to be alive.

The next day, the Ninth Aethyr described Crowley’s ascent from the Abyss and his arrival in the City of the Pyramids as a Magister Templi. Per its instructions, Crowley prostrated himself on the sand 1,001 times during the day’s march, reciting from the Qur’an:, Qul: Huwa Allâhu ahad; Allâhu alssamad; Lam yalid walam yûlad; Walam yakul lahu kufuwan ahad . 14

On December 8 they continued south, out of Bou-Sâada and toward the winter resort town of Biskra, over one hundred miles away. When one of Victor’s relatives arrived, worried for his safety, Crowley determined to let nothing interfere with their plans. “Where’s Victor?” Crowley was asked.

“There,” he replied, gesturing toward a dromedary. “I’ve turned him into a camel.” At that, he dismissed the chaperone and returned to his business.

Crowley and Neuburg followed the southbound road out of Bou-Sâada only to find it ran out after only a few miles. The rest of the day they walked through the Sahara, and that evening proceeded with the Eighth Aethyr.

The visions proceeded regularly throughout their march, describing the grade of Magus (9°=2°)—ninth in the hierarchy of ten grades and second from last—and Crowley’s final ascent as a Magister Templi into the Great White Brotherhood.

On December 16 they finally reached Biskra, a resort town full of palm trees and camels. They checked into the Royal Hotel, and Crowley dictated a thirteen-page letter to Fuller. In it, he dealt with Equinox business and complained incidentally about his difficulty in keeping Victor away from the bottoms of Arabic boys. While much has been made of this latter comment, it stands simply to reason that Crowley was dictating to none other than Neuburg, and that the comment was a joke; possibly one between Crowley and Neuburg, alluding to their own physical involvement. The poem “At Bordj-an-Nus,” which Crowley wrote at this time, sheds some light on this matter. When Crowley published it in The Equinox , he signed it as “Hilda Norfolk” to disguise its homosexual undertones:

The moon is down; we are alone;

May not our mouths meet, madden, mix, melt in the

starlight of a kiss?

El Arabi!

There by the palms, the desert’s edge, I drew thee to my

heart and held

Thy shy slim beauty for a splendid second; and fell

moaning back,

Smitten by Love’s forked flashing rod—as if the

uprooted mandrake yelled!

…

Great is the love of God and man

While I am trembling in thine arms, wild wanderer of wilderness!

El Arabi! 15

They called the Fourth Aethyr that evening at nine, learning more details about the Grade of Magus. The third, second, and first Aethyrs followed in rapid succession, wrapping up on December 19 at 3:30 in the afternoon.

With the conclusion of these visions, Crowley came to an understanding of the Great White Brotherhood and its three highest grades. He fathomed the sacrifices of the Abyss; understood how, as a Master of the Temple living in the City of the Pyramids under the Dark Night of Pan, he must interpret every event as a particular dealing of God with his soul; knew that as a Magus, he would become the Logos, the embodiment of the Word of the Aeon (Thelema) , but be cursed to have his speech interpreted as a lie; and learned about Babalon, who as a guardian of the Abyss gathered into her chalice the life blood of the Exempt Adept before he crossed the Abyss and, as the priestess or sacred prostitute of the Thelemic system, was the epitome of love under will. Reliving his ordeal of the Abyss and initiation into the Third Order, Crowley completely accepted The Book of the Law and felt genuinely secure in his chosen role as its prophet. Even though he had claimed the grade previously, he now fully understood the tasks of a Magister Templi and knew like never before that he had reached that grade.

Returning to Southampton in January 1910, Crowley kicked into high gear. Although he published various booklets for members of the A A

A —including Thelema

(the Holy Books in three volumes), “Liber Causae” (an account of the collapse of the GD and the A

—including Thelema

(the Holy Books in three volumes), “Liber Causae” (an account of the collapse of the GD and the A A

A ’s emergence therefrom,

included in Thelema

), and Liber Collegii Sancti

(a booklet in which to record the progress of students)—his most personal production was Rosa Decidua

, the fallen rose, the last in his series of poems about his ex-wife. The piece is a mournful dirge, a romantic lament over lost love:

’s emergence therefrom,

included in Thelema

), and Liber Collegii Sancti

(a booklet in which to record the progress of students)—his most personal production was Rosa Decidua

, the fallen rose, the last in his series of poems about his ex-wife. The piece is a mournful dirge, a romantic lament over lost love:

This is no tragedy of little tears.

My brain is hard and cold; there is no beat

Of its blood; there is no heat

Of sacred fire upon my lips to sing.

…

I have no memory of the rose-red hours.

No fragrance of those days amid the flowers

Lingers; all’s drowned in the accursèd stench

Of this damned present …

See! I reel back beneath the blow of her breath

As she comes smiling to me: that disgust

Changes her drunken lust

Into a shriek of hate—half conscious still

(Beneath the obsession of the will)

Of all she was—before her death, her death!

…

Who asks me for my tears?

She flings the body of our sweet dead child

Into my face with hell’s own epitaph

…

And all my being is one throb

Of anguish, and one inarticulate sob

Catches my throat. All these vain voices die,

And all these thunders venomously hurled

Stop. My head strikes the floor; one cry, the old cry,

Strikes at the sky its exquisite agony:

Rose! Rose o’ th’ World.

Crowley printed only twenty copies of the eleven-page poem to commemorate the divorce. It sported a green cover, with a friendly photograph of the poet with his wife and daughter, taken shortly before the court date, tipped in. Crowley dedicated the piece to Lord Salvesen, who presided over the trial. With Rosa Decidua , Crowley closed the door on a tragic phase of his life and bid farewell to his Rose of the World and her brother, Gerald of the Festuses.

Business at the Equinox

offices proceeded as usual toward publication of the next issue, set to contain a wide assortment of contributions: a description of the tasks for students in the A A

A ; Crowley’s “Aha!”; “The Shadowy Dill-Waters,” a spoof on Yeats; Baudelaire’s “The Poem of Hashish,” translated by Crowley; poems by Neuburg and Arthur F. Grimble; a story by Raffalovich; and two installments by Fuller—“The Treasure-House of Images” and the contentious “Temple of Solomon the King.”

; Crowley’s “Aha!”; “The Shadowy Dill-Waters,” a spoof on Yeats; Baudelaire’s “The Poem of Hashish,” translated by Crowley; poems by Neuburg and Arthur F. Grimble; a story by Raffalovich; and two installments by Fuller—“The Treasure-House of Images” and the contentious “Temple of Solomon the King.”

On March 11, solicitor George Rose Cran 16 appeared and served Crowley with a writ: Mathers was seeking an injunction to keep The Equinox from publishing the remaining GD ritual, its 5°=6° R.R. et A.C. 17 Or, in legalese, he was

restraining the defendant, his servants, and agents from publishing, or causing to be printed or published in the third number of the book or magazine known as The Equinox or otherwise disclosing any matter relating to the secrets, forms, rituals, or transactions of a certain order known as the Rosicrucian Order, of which the plaintiff was the Chief or Head. 18

“Balls,” Crowley cursed. The books were already printed and ready to be released in ten days. “Prophetically,” they offered a £10 reward for the source of a fictitious clipping sent to him:

Cox, Box, Equinox,

McGregors are coming to Town;

Some in rag, and some on jags,

And the Swami upside down.

Cran, Cran, MacGregor’s man

Served a writ, and away he ran. 19

This suggests he knew the writ was coming.

On March 14, Mathers applied for an ex parte interim injunction, which Justice Bucknill granted on March 18. One day after the spring equinox, March 21, Crowley’s appeal came before the court. Hearing the case were appeals judges Vaughan Williams, Fletcher Moulton, and Farwell. 20 The plaintiff, the Comte Liddell MacGregor, appeared with long white hair brushed straight back to reveal the withered features of his aging face. He was represented by Frederick Low and P. Rose-Innes. It was an impressive team: Sir Frederick Low (1856–1917) was admitted to the Middle Temple in 1890, invested as king’s counsel in 1902, and knighted in 1906; he would later serve as a member of Parliament for Norwich from 1910 to 1915, and as high court judge of the King’s Bench in 1915. 21 Sir Patrick Rose-Innes (1853–1924) was called to the bar in 1878, established a reputation as a Unionist lawyer and tariff reformer, and in 1905 was appointed recorder of Sandwich and Ramsgate; he would go on to be knighted in 1918. While this might seem an odd fit for the case, the hook may have originated with Rose-Innes’s role as provincial Masonic Grand Master for Aberdeenshire, which he would hold from 1905 to 1920: He may have been helping a fellow brother Mason, especially against someone breaking their oath of secrecy. 22

Crowley’s men were W. Whately and A. Neilson for the firm of Messrs. Steadman, Van Praagh, and Gaylor. William Whately (1858–1937) was a London-born Barrister-at-Law of the Inner Temple who would go on to be a Master of the Supreme Court. 23 Alexander Neilson (1868–1929) was educated at Fettes College and received his MA from Edinburgh University, passing his exam for the Middle Temple in 1891 and being called to the Bar in 1893; with a general practice in the Midland Circuit, “his kindly nature and pleasant manner made him many attached friends.” 24

The courtroom was packed. The last trial with this much interest occurred in 1905, when Mrs. Eliza Dinah Sheffield brought a breach of promise case against the Marquis Townshend; she claimed to be High Priestess of the Rosicrucian Order, but as of late she was known only as a West End hostess. The present trial promised to be just as colorful.

It began with Crowley’s man, Whately, reading Mathers’s affidavit:

I am the chief of the Rosicrucian Order. It is an order instituted in its modern form in 1888 for the study of mystical philosophy and the mysteries of antiquity. The order is upon the lines of the well-known institutions of Freemasonry.

The exclusive copyright of the rituals, ceremonies, and manuscripts of the order is vested in me, I being founder and compiler of them, and I claim such an interest in the same as will entitle me to restrain any infringement of my rights therein.

On November 18, 1898, Aleister Crowley, having duly qualified himself, signed the preliminary pledge form, to which it is requisite intending candidates for membership should subscribe their signatures. After compliance with the necessary formalities he became a member, and thereupon ratified the obligation of his signed pledge form by a solemn obligation in open Temple of the Order.

Throughout the reading, the justices smirked and sneered at the sworn testimony. Their response visibly displeased Mathers.

Whately handed a copy of the pledge form up to the bench, and continued to summarize the complaint. “The plaintiff claims the grossest possible breach of the defendant’s obligations and a serious infringement of the plaintiff’s right by publishing the order’s secrets in the second Equinox under the title ‘The Temple of Solomon the King.’ The article in question referred to the meetings of the Rosicrucian Order, and gave notice to the effect that the publication would continue in the March number.”

At that, Justice Williams chimed in, “Is it a romance?”

“I do not know, my lord. I cannot describe it.” After the laughter in the courtroom died down, Whately continued with his summary. “The plaintiff charges the matter to be printed in numbers three and four would continue the infringement.” Crowley, however, argued that Mathers was certainly not the head of the Rosicrucians, did not write the rituals, had not established any rights with respect to the material being published, and was not entitled to an injunction. “If there is any obligation to anybody it is to the society, and that cannot be a legal obligation, because they are a voluntary association and are not the plaintiffs.”

Williams asked Mathers’s counsel pointedly, “May I take it there is such a society as the Rosicrucians?”

“Yes,” Low replied, “there is.”

“And does the society have rules?”

“No, there are no rules of the society in fact, but there is a pledge of secrecy, which the defendant signed.” He indicated the copy of the pledge form which had been submitted to the bench.

“I see the plaintiff says he is ‘the earthly chief’ of the order, and subject to the guidance of the ‘spiritual’ order.”

Justice Farwell interrupted the questioning to ask, “What is the ‘spiritual order’?” The courtroom giggled in response.

“I cannot go into it, my lord,” Low apologized, “but it is clear the spiritual head would not be answerable for costs.” Laughter erupted from the observers.

Justice Moulton asked to see a copy of the second Equinox , and the thick tome was handed up to him. Low also asked the judges to read “The Pillar of Cloud,” a Rosicrucian piece by Mathers. As he read, Moulton’s lips curled into a delighted smile. The other judges similarly enjoyed Mathers’s article.

“The article is simply material which Comte Macgregor obtained from old books,” Whately complained for Crowley. “He can have no copyright in such material. Moreover, if publication of the next number of The Equinox is stopped, the publication will practically be stopped altogether, because the subscribers will be scattered. Although the plaintiff knew all about the subject matter of his complaint since November 11, he did not issue his writ until March 11, after the magazine had already been printed.”

“That is a question of pounds, shillings, and pence,” Justice Williams stressed, trying to return to the legal question of infringement.

“It is a very serious matter to my client.”

Low interrupted, “The plaintiff waited until the eve of publication because he was unable to locate Mr. Crowley’s address before then. Our complaint is that wherever our ritual was got from, it was a gross breach of faith for the defendant, after being admitted and allowed to attend the meetings—and then being expelled from the order—to start publishing this matter.”

“He has as much right to publish what is in the old books about the Rosicrucians as anybody else,” Justice Moulton argued.

“But he is not entitled to publish a ritual ceremony which he had pledged himself to secrecy about, even if it was got from the Bible.”

“Anybody who knows anything about these societies knows that the rituals of most of them have been published.”

“Your lordship must not ask me to admit that.”

Justice Williams, trying a different approach, interceded. “I have not observed any indication that you are, either of you, Masons.” The courtroom broke into laughter.

“I don’t propose to give your lordship any, either,” Low replied, generating even more laughter. “This society is in no way a Masonic society.”

Farwell selected several “strange and unpronounceable” words from the second Equinox and with a smile asked Mathers what they meant. Arouerist, Onnophris, Jokam. He could not—or would not—answer. Farwell shook his head in response. “I can understand the publication of a trade secret doing a person irreparable injury, but I cannot see how any damage, irreparable or otherwise, could be done by the publication in question.”

“If the initiation ritual is published in the March number, as Mr. Crowley proposes, the damage will be irreparable,” Low argued. “The cat would be out of the bag.”

Justice Williams replied, “But so much of the cat came out of the bag in September.”

Farwell added, “And I think it is a dead cat.” By this time, the courtroom roiled with laughter.

“Perhaps there is a second cat in the bag, my lord,” Low feebly tried to continue his argument. “If they have let out one, they may let out another. If you cannot stop this sort of thing by an injunction, there is practically no remedy at all. The defendant has been turned out of the order, and is publishing the article as an act of revenge for having been expelled.”

In the end, the Justices ruled that Mathers had waited too long to file an injunction: he could have done it a month or six weeks ago, before Crowley had gone to the expense of printing The Equinox . Based on the content of the second issue, they ruled the third issue would do the plaintiff no harm. Therefore, Mathers was not entitled to restrain the publication in question. Crowley was allowed to publish The Equinox and was awarded costs as well.

Response to the trial was overwhelming. Virtually every London newspaper sported headlines like “Secret Society: Amusing Comedy in Appeal Court,” “Rosicrucian Rites: The Dread Secrets of the Order Revealed,” “Secrets of a Mystic Society: Rosicrucian Ritual to Be Revealed,” and “Secrets of the ‘Golden Dawn’: Quaint Rites of the Modern Rosicrucians.” 25 Everybody knew about the magician Aleister Crowley, who was publishing the Rosicrucians’ secrets. Many papers even excerpted rituals from the victorious Equinox .

Most significantly, as the Evening News reported, “The revelations of Mr. Crowley have created utter consternation in the ranks of the Rosicrucians.” 26 Crowley’s publication of the rituals, however, upset far fewer than did Mathers’s claim to leadership of the Rosicrucian Order. As a result, Crowley was “invaded by 333 sole and supreme Grand Masters of the Rosicrucians,” 27 all of whom conferred upon him membership in their organizations. One of these was Theodor Reuss (1855–1923), head of the German organization Ordo Templi Orientis, which Crowley would come to embrace and direct in later years. At the time, however, he simply “booted [Reuss] with the other 332.” 28

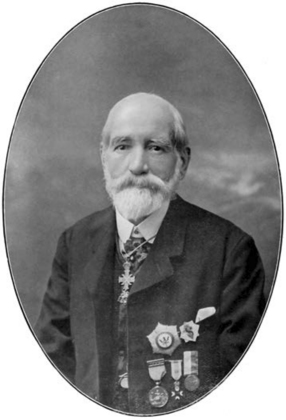

Crowley also became acquainted at this time with John Yarker (1833–1913), a collector of patents to operate various clandestine and pseudo-Masonic lodges, all of which he believed to predate the Ancient and Accepted Rite (i.e., “legitimate” Freemasonry), or at the very least to be just as legitimate. Foremost amongst these was the Ancient and Primitive Rite of Masonry, or of Memphis-Mizraim, which was an amalgamation of two older rites of ninety-six and ninety degrees, respectively, over which Yarker was Supreme Grand Master General. Despite being embattled within and ultimately expelled from the Ancient and Accepted Rite because of his fringe interests, 29 he continued to be an active Masonic scholar, contributing regularly to Masonic publications, including the prestigious journal Ars Quatuor Coronatorum . 30 Many of his ideas in the journal, however, fell on deaf ears. It was in fact Crowley’s positive review of Yarker’s The Arcane Schools (1909) that initially prompted Yarker to contact Crowley and thus initiate correspondence with an appreciative listener. 31 Yarker, as did so many other groups, bestowed on Crowley high rank in various orders. As a result of these deluges of dignities, the list of honors conferred on Crowley at this time filled four dense pages. 32

Illustrious Brother John Yarker (1833–1913) in his later years. (photo credit 9.2)

The publicity resulted in a boom year for the A A

A . Whereas sixteen probationers signed up in 1909, twenty-six joined in 1910. Among these were G. M. Marston, Frank Bennett, J. G. Bayley, Herbert Close, and J. T. Windram.

. Whereas sixteen probationers signed up in 1909, twenty-six joined in 1910. Among these were G. M. Marston, Frank Bennett, J. G. Bayley, Herbert Close, and J. T. Windram.

Commander Guy Montagu Marston (1871–1928) served in the Royal Navy as “one of the highest officials of the Admiralty.”

33

He was born at Rempstone Hall, Dorset, to Rev. Charles D. Marston and Katharine Calcraft. Enlisting in the Royal Navy, he advanced to sublieutenant in 1892, and shortly

thereafter served under Rear-Admiral Bedford on three punitive expeditions to the Gambia (February 1894), the Republic of Benin (September 1894), and Niger (February 1895). In 1901, Marston succeeded his uncle, William Montagu Calcraft, at Rempstone. The same year, he was made a full lieutenant, and in 1905 was promoted to commander, serving with the Hydrographic Department of the Admiralty. He was a friend of English poet Rupert Brook, whom W. B. Yeats had called “the handsomest young man in England”; Brook was also a friend of Equinox

contributor G. H. S. Pinsent, which may provide the connection to Crowley. Marston was an avid reader, and his library reveals an interest in the sexual researches of Freud, Krafft-Ebing, and Havelock Ellis. Marston’s own experiments on the psychology of married Englishwomen demonstrated—he believed conclusively—that shamanic drumming made them restless, intensifying until it resulted in “shameless masturbation or indecent advances.”

34

His interest in ritual magic led him to join the A A

A on February 22, 1910, with the motto “All for knowledge.” On November 12, 1910, he would take command of the Blanche

cruiser and leave for Devonport.

35

on February 22, 1910, with the motto “All for knowledge.” On November 12, 1910, he would take command of the Blanche

cruiser and leave for Devonport.

35

Frank Bennett (1868–1930) was a Lancashire bricklayer who, due to personal hardships, worked with his hands since age nine. Magic and Theosophy had interested him for a long time, and he wrote Crowley in the winter of 1910 to ask his advice on a practical course of study. Crowley recommended the Abramelin operation, adding, “I am glad to hear that you are really at work. So many people now-a-days just prattle about magic, and never do any.” 36 To help him along, Crowley sent him a copy of The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage .

Bennett did as instructed but soon sent an alarmed letter to Crowley because he was hearing voices in his head. Crowley wrote back, reassuring:

What you report is rather good in a way, because it shows you are getting some results. But of course it implies also that your sphere is not closed. I should use the banishing Rituals of Hexagrams and Pentagrams to begin and end each meditation and also assumption of the God-form of Harpocrates. I think I should do less reading and more gardening; and in particular I should go to a doctor and make sure that the symptoms are removed so far as they are physical. 37

Here is Crowley at his best as a teacher: rule out medical problems; barring this, work in a more controlled environment and, most importantly, don’t try too hard. The advice must have worked, as the problem did not come up again.

Bennett joined the A A

A as “Sapienta Amor Potentia” (Love of wisdom is power) on March 12, 1910. In order to check on this potential student, Crowley sent his student Herbert Inman to call on him. Inman learned that Bennett shared his interest in Co-Masonry, a new movement in Freemasonry that admitted women alongside men in its ranks. The nature of their conversation is unknown, but shortly afterwards Inman left for Rio and set up a TS

lodge. Despite threat of expulsion, Bennett pursued Theosophy instead of the A

as “Sapienta Amor Potentia” (Love of wisdom is power) on March 12, 1910. In order to check on this potential student, Crowley sent his student Herbert Inman to call on him. Inman learned that Bennett shared his interest in Co-Masonry, a new movement in Freemasonry that admitted women alongside men in its ranks. The nature of their conversation is unknown, but shortly afterwards Inman left for Rio and set up a TS

lodge. Despite threat of expulsion, Bennett pursued Theosophy instead of the A A

A and moved to Australia in 1911.

38

and moved to Australia in 1911.

38

James Gilbert Bayley joined the A A

A on March 22, 1910, taking the motto “Perfectio et Ministerium” (Perfection and service). Although Crowley initially considered him a doubtful member, having been brought in under Inman, he would stand by Crowley throughout his life, serving as his British liaison while he was out of the country in the 1920s and staying in close touch through his final years.

39

on March 22, 1910, taking the motto “Perfectio et Ministerium” (Perfection and service). Although Crowley initially considered him a doubtful member, having been brought in under Inman, he would stand by Crowley throughout his life, serving as his British liaison while he was out of the country in the 1920s and staying in close touch through his final years.

39

Herbert H. Close (1890–1971) was an old friend of Fuller’s, born to a well-to-do family of land owners. Under the pen name Meredith Starr, he was a writer and poet interested in mysticism, aromatherapy, and homeopathy, and described himself as a “constructive psychologist.” He was also a contributor to The Occult Review . 40 Shortly after joining on June 6, 1910, Frater Superna Sequor (I follow the gods) began experiments with Crowley’s drug of choice, the hallucinogen Anhalonium lewinii , commonly known as peyote. 41 After an astral journey convinced Close that he had attained a high grade, Crowley tested his claimed ability to stave off the effects of any drug by giving him ten grains of calomel. A note from Crowley to Fuller sheds light on this meeting: “I saw Starr & slew him. I hope he’ll be all right soon. I’ve given him a week to study Kant and a fortnight to get Kunt.” 42 Close’s poem “Memory of Love” appeared in The Equinox I(7), but he eventually parted with AC, most likely when Fuller did, and later briefly became a follower of Indian guru Meher Baba (1894–1969), helping bring him to the West in the early 1930s. Crowley bitterly assessed the student: “Went out of his mind and never came back.” 43

James Thomas Windram (1877–1939) was a South African accountant who joined the A A

A on August 11, 1910. He chose the magical name of “Servabo Fidem” (I serve the faith), and was one of only eight students who Crowley passed to Neophyte. Like Bayley, he stuck by Crowley for many years, taking on the A

on August 11, 1910. He chose the magical name of “Servabo Fidem” (I serve the faith), and was one of only eight students who Crowley passed to Neophyte. Like Bayley, he stuck by Crowley for many years, taking on the A A

A motto “Semper Paratus” (Always ready) and eventually becoming OTO National Grand Master for South Africa under the title of Mercurius X°.

motto “Semper Paratus” (Always ready) and eventually becoming OTO National Grand Master for South Africa under the title of Mercurius X°.

On April 1, Crowley also admitted into the A A

A Australian violinist Leila Ida Nerissa Bathurst Waddell (1880–1932). who would become one of his most important magical partners. Leila Waddell was the daughter of David Waddell and Ivy Lea Bathurst of Randwick, New South Wales. She was born in Bathurst, New South Wales, a city whose largely aboriginal population was transformed by the 1851 discovery of gold and the 1876 completion of a railway from Sydney. She took violin lessons from age seven, quickly mastering her instrument. However, when her tutor died, it became clear that she was playing by memorizing her teacher’s performance, without either reading music or understanding theory. So she got a new tutor and started over.

44

She was trained by Henri Stael, principal violinist with the Pleyel Concert Company, and in the 1898 annual examinations at the Sydney College of Music she

was first runner-up for a medal in advanced honors in violin.

45

She began teaching in suburban Sydney: at Presbyterian Ladies’ College, a day and boarding school in the western suburb of Croydon, where she taught Junior Violin from 1901 to 1905; at Ascham, a nondenominational girls boarding school in the eastern suburb of Edgecliff, until March 1907; and at Kambala, an Anglican day and boarding school for girls in the eastern suburb of Rose Bay.

46

Australian violinist Leila Ida Nerissa Bathurst Waddell (1880–1932). who would become one of his most important magical partners. Leila Waddell was the daughter of David Waddell and Ivy Lea Bathurst of Randwick, New South Wales. She was born in Bathurst, New South Wales, a city whose largely aboriginal population was transformed by the 1851 discovery of gold and the 1876 completion of a railway from Sydney. She took violin lessons from age seven, quickly mastering her instrument. However, when her tutor died, it became clear that she was playing by memorizing her teacher’s performance, without either reading music or understanding theory. So she got a new tutor and started over.

44

She was trained by Henri Stael, principal violinist with the Pleyel Concert Company, and in the 1898 annual examinations at the Sydney College of Music she

was first runner-up for a medal in advanced honors in violin.

45

She began teaching in suburban Sydney: at Presbyterian Ladies’ College, a day and boarding school in the western suburb of Croydon, where she taught Junior Violin from 1901 to 1905; at Ascham, a nondenominational girls boarding school in the eastern suburb of Edgecliff, until March 1907; and at Kambala, an Anglican day and boarding school for girls in the eastern suburb of Rose Bay.

46

With the press dubbing her “a very clever violiniste,” 47 she—along with a pianist, contralto, and bass—played a Grand Concert on January 21, 1904, under the management Walter E. Taylor. Selections included Grieg’s Sonata No. 3 in C Minor (Opus 45) and Wieniawski’s “Cappricio-Valse” in E major (Opus 7), both for violin and piano. This latter piece she played “with great delicacy and brilliancy, exciting prolonged applause.” After two recalls, “her virtuosity being amply demonstrated,” “the talented young lady” returned with “Le Cygne,” the thirteenth movement of Saint-Saëns’s Carnival of Animals; the “Romance” from Wieniawski’s Violin Concerto No. 2; and Bohm’s “Papillons.” 48 In August 1905, she debuted as a soloist at a Sydney Town Hall concert recital given by Arthur Mason, dubbed “one of our busiest musicians” for his jobs as City Organist, organist at St. James’ Church, and director of the Sydney Choristers. 49 A 1906 concert was held to honor the celebrated violinist’s charitable works. 50 This attracted the attention of Henry Hawayrd, who hired her for the Brescians, a group of Anglo-Italian instrumentalists and vocalists who served as the movie-theater orchestra for T. J. West’s West Pictures in New Zealand. Works performed by Waddell at this time included Charles Flavell Hayward’s “Grand Concert Duet (Olde Englande) on English Airs, for Two Violins” (with Auelina Martinego) and Francesco Paolo Tosti’s song “Beauty’s Eyes,” with violin accompaniment and obligato. 51

Waddell played with the Brescians from 1906 to 1908, when she left for England to hone her craft. This is likely when she studied with world-class violin teacher Émile Sauret (1852–1920), who was teaching in England at this time; several years later, she would also study with Leopold Auer (1845–1930) in New York. 52 Success followed her, as the Sydney Mail reported in June 1909, that “the well-known Sydney violinist has been meeting with marked success at Bournemouth.” 53 Soon she was performing as part of the Ladies’ Orchestra in George Edwardes’s revival of Oscar Straus’s A Waltz Dream , which opened at Daly’s Theater in Leicester Square on January 17, 1911. While the Times reviewer was admittedly jaded by having seen previous productions and thus gave the show a lukewarm reception, The Play Pictorial raved. 54 The show ran for 106 performances through the end of April 1911. 55

Part Maori, Leila Waddell had square brusque features and thick eyebrows, nose, and lips. Her straight dark hair reached down to her waist. She was slender, attractive, and exotic, and Crowley fell madly in love with her. He dubbed her “the Mother of Heaven”—often referring to her simply as “Mother”—and through her the “purely human side of his life reached a proper climax.” 56 She became one of the most intriguing and important figures in Crowley’s life. Within a week of her acquaintance, he was inspired to write “The Vixen” and “The Violinist.” The first is an occult-horror short story about an heiress who uses black magic against her lover. The latter belongs to the same genre, about a woman who evokes a demon from one of the watchtowers though her music. In these pieces he portrayed Leila as happy, honest, shrewd, and huntress lithe. During a May trip to Venice, Crowley wrote The Household Gods , also dedicated to her. Penned at Hôtel Pallanza in Lago Maggiore, he called it “a charming little play showing how heaven confused a domestic quarrel between husband and wife.” 57 In his Confessions , Crowley admitted a secret affection for this piece, and the writer Louis Wilkinson claimed it contained one of the funniest exclamations in literature. 58

The Ladies’ Orchestra for George Edwardes’s revival of A Waltz Dream , 1911. (photo credit 9.3)

Crowley noted that since the Mathers trial, “For the first time, I found myself famous and my work in demand.” 59 His poem about the Sahara, “The Tent,” appeared in the March 1910 Occult Review , 60 followed in the May issue by a long discussion of the court case.

His next book was The Scented Garden . Purportedly translated from a rare Indian manuscript by the late Major Lutiy and another, it was fully titled The Scented Garden of Abdullah the Satirist of Shiraz . It appeared early in the year, was printed anonymously, and was issued privately in an edition of two hundred copies. Written during Crowley’s Asian wanderings, it was his parody of the Iranian poets and their texts on mysticism and homosexual love. It was also a tribute to his hero, Sir Richard Burton, whose scholarly books on sexual customs of the near and far east had caused a moralistic stir. “The Scented Garden deals entirely with pederasty, of which the author saw much evidence in India,” Crowley wrote of his book. “It is an attempt to understand the mind of the Persian, while the preliminary essay does the same for the English clergyman.” 61 When he wrote these words in 1913, most copies of the book had been seized and destroyed.

In the preface to his next book, Crowley wrote “In response to a widely-spread lack of interest in my writings, I have consented to publish a small and unrepresentative selection from the same.” This anthology was Ambergris , published by Elkin Matthews. In typical manner, Crowley ran up £6 worth of proof corrections. He found the charges astronomical, and attacked the printer during his review of the book in the fourth Equinox . The investment was worthwhile, however, as the Evening Post declared it “the most interesting volume of new English verse seen this year.” 62 The Nation found Crowley “as passionately possessed by his theme as any poet has ever been. 63 The New Age similarly declared that any lack of interest was attributable to the high price of his lavish editions, adding “Mr. Crowley is one of the principal poets now writing.” 64 D. H. Lawrence (1885–1930)—his The White Peacock (1911) not yet published and his famous Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) nearly two decades off—disliked the book, remarking, “If Ambergris smells like ‘Crowley,’ it is pretty bad. Civet cats and sperm whales—ugh!” 65 Ironically, Crowley and Lawrence would both be underdogs of the Mandrake Press stable some twenty years later.

The Winged Beetle collected many of Crowley’s newer works, some reprinted from previous works 66 and others appearing for the first time. He dedicated its poems to various people in his life, including G. C. Jones, Euphemia Lamb, Austin Spare, Lord Salvesen, Raymond Radclyffe, Kathleen Bruce, Rose Crowley, Commander Marston, Elaine Simpson, J. F. C. Fuller, Victor Neuburg, Frank Harris, Norman Mudd, H, Sheridan-Bickers, Allan Bennett, Mary Waska, George Raffalovich, and his mother. Yielding to his publisher’s concern that verse three of the dedication was too indelicate, Crowley consented to pen a less offensive substitute. However, the book’s “Glossary of Obscure Terms” allowed readers to translate it back to read:

Yea! God himself upon his throne

Cringed at thy torrid truculence;

Tottered and crashed, a crumbled crone,

at thy contemptuous ‘slave Get hence!’

Out flickered the Ghost’s marish tongue,

And Jesus wallowed in his dung.

It also featured a poem called “The Convert (A Hundred Years Hence),” which took a tongue-in-cheek view of his current popularity:

There met one eve in a sylvan glade

A horrible Man and a beautiful maid.

“Where are you going, so meek and holy?”

“I’m going to temple to worship Crowley.”

“Crowley is God, then? How did you know?”

“Why, it’s Captain Fuller that told us so.”

Fuller also had the honor of designing the book cover and having the volume as a whole dedicated to him. It remains one of the best anthologies of Crowley’s works, and the press received it enthusiastically. A critic with the Occult Review wrote:

I declare that Aleister Crowley is among the first of living English poets. It will not be many years before this fact is generally recognized and duly appreciated.… The range of his subjects is almost infinite … his poems are ablaze with the white heat of ecstasy, the passionate desire of the Overman towards his ultimate consummation, reunion with God. 67

Alas, Crowley was about to learn the press was quite fickle.

Leila Waddell (1880–1932). (photo credit 9.4)