CHAPTER TEN

Aleister Through the Looking Glass

The pungent smell of burning tobacco filled the Dorset home of Commander Marston on May 9, 1910, as he hosted an A A

A ritual based on the lessons learnt in Algiers. The ceremony was designed to summon Bartzabel, spirit of Mars, and the burning of his incense, tobacco, was intended to make the residence more conducive to his appearance. Just as Crowley had sat in the Triangle of the Art during the call of the Tenth Aethyr, so Neuburg now sat in the space reserved for the spirit, ready to act as its conduit. As the ceremony proceeded, Neuburg entered a trance, rose to his feet, and to everyone’s surprise, danced an unscheduled dervish. When the dance ended and Victor began to speak as the god of war, they realized that Bartzabel was among them.

ritual based on the lessons learnt in Algiers. The ceremony was designed to summon Bartzabel, spirit of Mars, and the burning of his incense, tobacco, was intended to make the residence more conducive to his appearance. Just as Crowley had sat in the Triangle of the Art during the call of the Tenth Aethyr, so Neuburg now sat in the space reserved for the spirit, ready to act as its conduit. As the ceremony proceeded, Neuburg entered a trance, rose to his feet, and to everyone’s surprise, danced an unscheduled dervish. When the dance ended and Victor began to speak as the god of war, they realized that Bartzabel was among them.

Marston asked the obvious question: “Will nation rise up against nation?” Bartzabel, through Neuburg, warned them that two wars would break out within the next five years. The first would center on Turkey, the second in Germany. The conflicts would destroy both nations. (The prediction would prove to be correct, with the Balkan War in 1912 and World War I in 1914.)

Although the ritual was an unqualified success—it was the most startling and concrete magical result Crowley had known so far—its significance comes from neither Neuburg’s channeling nor the accurate prediction. The ritual is important because Marston, impressed with the ceremony, half-jokingly suggested they charge admission and perform it publicly. Crowley’s eyes lit up, and he replied, “I think you may be on to something.”

Parry, gravely concerned about the moral character of this frequent campus visitor, summoned Norman Mudd to his office. Mudd, aside from being a Crowley devotee, was also secretary of the Cambridge Freethought Association, which Ward had formed under AC’s direction to host his talks on campus. Dean Parry—explaining that he objected not to Crowley’s talks but to his morality—instructed Mudd to cancel the Freethought Association’s invitation and cease distributing copies of The Star in the West

. Given that AC had just won a popular court case, Parry chose his words carefully to avoid slander.

Outraged, Mudd summoned the Freethought Association’s other members, who sent their rebellious reply to the Dean:

The Association having taken into consideration the request made to it by the Dean of Trinity regrets that it finds itself unable to comply with the request. It regards the right to invite down any person it thinks fit as essential to its principles and wishes to point out that its attitude towards any opinions advocated before it is purely critical.

2

Crowley, meanwhile, fumed that someone—a “Parry-lytic Liar,” as Crowley dubbed him

3

—should accuse him behind his back: shades of Champney! So he wrote Mudd’s father, claiming his son’s tutors were “indulging in things so abominable that among decent people they have not even a name,”

4

and recommended he place his son in the charge of more probitous tutors. That summer, Crowley came to Cambridge as scheduled.

Having failed to control the Freethought Association, Parry had no recourse but to single out one of them and issue an ultimatum. Indeed, Parry has been criticized “for a certain peremptoriness and a tendency to override opposition.”

5

The ax fell on Mudd: he was to resign as secretary of the Freethought Association, write the dean a letter of apology, and promise on his honor as a gentleman never again to contact Aleister Crowley. If he refused, Parry would cancel his scholarship.

Mudd crumbled. As he later recounted, “I will not go into details as to the fight I put up. It was stubborn but unskillful and I was compelled ultimately to give in. You must understand that at this time I was quite poor, having gone up to Cambridge only with the help of scholarships.”

6

That scholarship was his only means of staying in college, and his parents were already hundreds of pounds in debt over his other educational expenses. Set on an academic career, he had no choice but to comply: to resign and apologize. However, he secretly maintained his correspondence with Crowley.

Cambridge banned Crowley, and the battle was over for now. The incident would prompt AC’s poetic critique “Athanasius Contra Decanum,” eventually published in The Equinox

.

In the silent moments following the conversation, Crowley was spiritually charged and uplifted. So, he learned, were his friends. It felt as though they’d just done some powerful, primal ritual. Notions from this performance and the ritual at Marston’s house met and joined: Neuburg’s dance, Leila’s music, and Crowley’s poetry were all powerful adjuncts to dramatic ritual. Based on this sketchy theme, AC wrote two poems to the Mother of Heaven: “The Interpreter” and “Pan to Artemis.” Both are frenetic and infectious invocations:

Uncharmable charmer

Of Bacchus and Mars

In the sounding rebounding

Abyss of the stars!

O virgin in armour,

Thine arrows unsling

In the brilliant resilient

First rays of the spring!

Of love, when I broke

Through the shroud, through the cloud,

Through the storm, through the smoke,

To the mountain of passion

Volcanic that woke—

By the rage of the mage

I invoke, I invoke!

7

On August 23 these elements coalesced into the Rite of Artemis, performed at the Equinox

offices for the press and public. Its name and form were more than a passing nod to the Matherses’ “Rite of Isis” in Paris a decade before.

With lights dimmed, incense burning, and all clad in their magical robes, the rite began with the banishing ritual of the pentagram and purifications of the temple with water and fire. With the space duly cleared and consecrated, Crowley led the others in a circumambulation around the altar. One brother passed the Cup of Libation around the room while another recited poetry. After invoking Artemis via the Greater Ritual of the Hexagram, another libation celebrated the deity. A third libation followed AC’s reading of “Song of Orpheus” from Argonauts

.

Speculation surrounds the contents of this libation: although reporter Raymond Radclyffe described the concoction as pleasant smelling, attendee Ethel Wieland said it tasted like rotten apples and made her intoxicated for a week. The liquid clearly contained some active ingredient, for Neuburg wrote to the Wielands after the performance, “I am glad the effects of the drug have passed off from Mrs. Wieland and yourself.”

8

Neuburg’s biographer Jean Overton Fuller claimed the drug was opium, although Crowley himself gave the best

explanation: to generate a bacchic exuberance without intoxicating patrons with wine, he opted instead for “the elixir introduced by me to Europe”—Anhalonium lewinii

or mescal buttons infused with herbs, fruit juices, and alcohol—with instructions to skip anyone who showed signs of drunkenness. At this time, no laws prohibited the use of such substances.

Following the preliminaries, the brethren led in and enthroned on a high seat the Mother of Heaven. Solemn and reverent, Crowley recited Swinburne’s first chorus from “Atalanta.”

9

Another libation, an invocation to Artemis, and further ceremonies followed. The rite took on a greater energy when Crowley commanded Neuburg to dance “the dance of Syrinx and Pan in honour of our lady Artemis.” Neuburg danced with beauty and grace until he collapsed from exhaustion in the middle of the room, staying there for the remainder of the rite. Crowley recited another poem to Artemis, and after a deathly silence, the Mother of Heaven took her Guarnerius violin and played. Her performance was sensual, subtle, masterful. The stunned audience was wafted away by the very ecstasy Crowley had hoped to produce.

The long, intense silence ended when Crowley announced, “By the Power in me vested I declare the Temple closed.”

Raymond Radclyffe reviewed the ceremony for the August 24 edition of The Sketch

, calling it “beautifully conceived and beautifully carried out. If there is any higher form of artistic expression than great verse and great music, I have yet to learn it.”

10

Radclyffe hailed from an old and distinguished family, beginning as a financial journalist and editor at St. Stepehen’s Review

, where his partner, William Allison, called him “a singularly able man.”

11

As a signatory on the paper’s parent company, Radclyffe was named in a libel suit against St. Stephen’s Review;

although protesting innocence, the lawsuit and other financial troubles doomed the paper.

12

He personally suffered financially, appearing in court to account for over £5,000 in unpaid debt.

13

He recovered and continued to write, contributing to London’s Financial Times

and publishing his memoir, Wealth and Cats

, in 1898.

14

During the 1910s he would go on to be financial editor for the New Witness

, regular financial commentator for The English Review

, and author of The War and Finance;

15

he beame so influential that his word could bolster how the public perceived the integrity of any new company or undertaking.

16

According to AC, Radclyffe, “though utterly indifferent to Magick, was passionately fond of poetry and thought mine first-class, and unrivalled in my generation.”

17

Theirs was a deep friendship, Crowley writing appreciatively of him, “he was one of the very best that ever lived; a City Editor straight as Euclid before Einstein attacked him, and one of the best literary critics and friends in the world.”

18

This explained his presence at the Rite of Artemis, and AC appreciated the good review, inscribing a copy of Clouds without Water

to “Raymond Radclyffe from his grateful friend Aleister Crowley.”

19

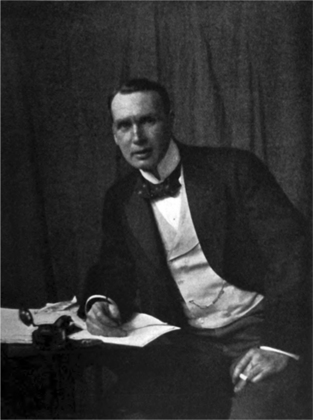

Financial writer and editor Raymond Radclyffe, c. 1898. (photo credit 10.1)

Radclyffe’s positive review encouraged Crowley to compose and perform an entire series of rites. Although Fuller and his friends urged Crowley to leave well enough alone, Crowley stubbornly rented a room at Westminster’s Caxton Hall. To this respectable venue accustomed to whist drives, subscription dances, and meetings of the fledgling suffragettes, Crowley planned to introduce incense, music, chanting, and dancing for the ritual of all rituals.

Ethel Archer, an aspiring poet in her early twenties, came aboard early enough to attend the Rite of Artemis. Ethel Florence E. Archer (b. 1885) was the fourth of five children, born in Slougham, Sussex, to Ormond A. Archer, curate of Whitbourne, and his wife, Emily.

20

Although she had written The Book of Plain Cooking

,

21

she sought creative outlets through fiction and poetry. In 1908 she married artist Eugene John Wieland (c. 1880–1915), son of Thomas Thatcher and Eugenie Wieland of Sunnyfield House, Guisborough, Yorkshire;

22

she nicknamed him “Bunco.” They were passionate lovers, as anonymously documented in a popular article written by a neighbor who watched their unselfconscious behavior through the open window of their

“shabby old garret,” which was furnished with little more than an easel, two chairs, and a mirror.

23

Both Ethel and Eugene became heavily involved with both OTO and A A

A at this time, and Crowley would encourage Eugene to set up the publishing imprint Wieland & Co., which over the next couple of years would bring out subsequent issues of The Equinox

, and several of Crowley’s other works.

24

Archer’s contributions to The Equinox

were limited to love poems, and Neuburg, noting that these addressed women, teasingly dubbed her Sappho; meanwhile, she was surprised that someone as fey as Neuburg would point the finger. Although she explained to everybody’s satisfaction that her poems described how she imagined a man might see her, she nevertheless adopted Sappho as her colorful moniker. Both Neuburg and Crowley intrigued her, and she spent long hours at the Equinox

offices. Both she and Wieland would eventually part with Crowley, and Wieland would go on to serve with the 19th Battalion in the Great War, reaching the rank of sergeant. He would die in a Canadian hospital on October 5, 1915, as a result of injuries sustained at Loos, and be buried at Le Treport Military Cemetery.

25

Archer would continue to publish occasional books, poetry, and essays throughout her life.

26

at this time, and Crowley would encourage Eugene to set up the publishing imprint Wieland & Co., which over the next couple of years would bring out subsequent issues of The Equinox

, and several of Crowley’s other works.

24

Archer’s contributions to The Equinox

were limited to love poems, and Neuburg, noting that these addressed women, teasingly dubbed her Sappho; meanwhile, she was surprised that someone as fey as Neuburg would point the finger. Although she explained to everybody’s satisfaction that her poems described how she imagined a man might see her, she nevertheless adopted Sappho as her colorful moniker. Both Neuburg and Crowley intrigued her, and she spent long hours at the Equinox

offices. Both she and Wieland would eventually part with Crowley, and Wieland would go on to serve with the 19th Battalion in the Great War, reaching the rank of sergeant. He would die in a Canadian hospital on October 5, 1915, as a result of injuries sustained at Loos, and be buried at Le Treport Military Cemetery.

25

Archer would continue to publish occasional books, poetry, and essays throughout her life.

26

As one of Chelsea’s great hostesses, Elizabeth Gwendolen Otter (1876–1958)

27

considered herself unshockable. Her Sunday luncheons attracted all manner of actors, painters, and writers; she even took in her fair share of them. A friend introduced her to Crowley because of her fascination with the odd and unconventional. AC was an admirable addition to her collection of personalities, and the magician became good friends with this plain-looking woman who claimed descent from Pocahontas. She contributed her opinions to the book review section of The Equinox

,

28

while he in turn dedicated “The Ghouls”

29

to her and portrayed her in Moonchild

(1929) as Mrs. Badger.

Vittoria Cremers could have been a storybook figure: she was born Vittoria Cassini around 1859 in Pisa to the Italian Manrico Vittorio Cassini and his British wife, Elizabeth Rutherford. Vittoria made her way to New York, where she was proprietor and editor of the Stage Gazette

. Around February 1886 she married Russia’s Baron Louis Cremers, who was the son of a famous St. Petersburg banking family, the Rothschilds, with a net worth of $40 million. A couple of weeks after the wedding, she reportedly told her husband that she “could not possibly love any man.”

30

It was at this time that he learned of her habit of going out on the town dressed as a man, and Crowley later reports that “She boasted of her virginity and of the intimacy of her relations with Mabel Collins, with whom she lived a long time.”

31

The Baron and Cremers soon separated, then divorced; Vittoria got a butch haircut and began answering simply to “Cremers.” Mabel Collins (1851–1927) was a Theosophist and novelist whose novel The Blossom and the Fruit

(1890) Crowley admired enough to include in the A A

A reading list; he considered it “the best existing account of the Theosophic theories presented in dramatic form.”

32

While Collins and Crowley never met, their mutual acquaintance Cremers doubtlessly

saw parallels: Just as Crowley was editor of The Equinox

, Collins was H. P. Blavatsky’s coeditor of the Theosophical periodical Lucifer

. And just as Crowley claimed to scribe various “Holy Books” dictated by the Secret Chiefs, so too did Collins claim that her books Idyll of the White Lotus

(1884), Light on the Path

(1885), and Through the Gates of Gold

(1887) were dictated by Koot Hoomi, one of the Masters or Mahatmas who guided Blavatsky.

33

Cremers often repeated Collins’s claim to know the identity of Jack the Ripper, and Crowley preserved the claim in “Jack the Ripper.”

34

reading list; he considered it “the best existing account of the Theosophic theories presented in dramatic form.”

32

While Collins and Crowley never met, their mutual acquaintance Cremers doubtlessly

saw parallels: Just as Crowley was editor of The Equinox

, Collins was H. P. Blavatsky’s coeditor of the Theosophical periodical Lucifer

. And just as Crowley claimed to scribe various “Holy Books” dictated by the Secret Chiefs, so too did Collins claim that her books Idyll of the White Lotus

(1884), Light on the Path

(1885), and Through the Gates of Gold

(1887) were dictated by Koot Hoomi, one of the Masters or Mahatmas who guided Blavatsky.

33

Cremers often repeated Collins’s claim to know the identity of Jack the Ripper, and Crowley preserved the claim in “Jack the Ripper.”

34

Cremers was a sincere but penniless seeker, transcribing 777

in New York’s Astor Library because she could not afford to purchase a copy. She wished to help “put the Order over,” as Crowley called it, so AC paid her passage to England and introduced her to his circle. Aged in her fifties, she had white hair and unhappy eyes. Her stern, square face, yellow and hard, reminded Crowley of wrinkled parchment. When she boasted of her undercover work against New York’s drug and prostitution rings, Crowley could more readily believe that she directed

drug and prostitution traffic than fought it. “Crowley is one of three things,” she once said of her mentor. “He is either mad, or he is a blackguard, or he is the greatest adept.”

35

Crowley also got to know W. E. Hayter Preston (b. 1891), a close friend of the Neuburg family, who acted as Victor’s watchdog. Like Victor, he was a Freethinker and poet. Although he worked as a freelance journalist, he soon became literary editor at the Sunday Referee

. Preston, who studied Lévi and the French magicians before he ever met Neuburg, took a dim view of Crowley. A dinner with AC and his mother helped solidify this opinion: according to Preston, Crowley snatched the menu out of his mother’s hands and, closing it, told her, “Mother, you may have boiled toads. Or fried Jesu.”

36

Jeanne Eugenie Heyse (1890–1912) was a young actress and dancer at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, her tuition paid by a local businessman. She was the oldest of three sisters, born in Edmonton, Middlesex, to Holland-born wholesale merchant Ferdinand Francis E. Heyse and his Irish wife, Margaret.

37

Under her stage name Ione de Forest, her major previous experience was playing The Blue Bird

(1909) by Belgian playwright and winner of the 1911 Nobel Prize for Literature Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949). Joan, as she preferred to be called, had no interest in the occult, but she entered Crowley’s circle when she answered an ad in Stage

seeking dancers for a performance at Caxton Hall. Her body was as gaunt and cadaverous, and the pale powders she wore made her anemic skin even more pallid. Black hair dangled to her slight waist, and golden eyes beamed vacantly from her oval face. Beautiful and sweet, she could be manic one moment, melancholic the next. Indeed, two years later her newlywed husband would describe her: “She was in poor health, highly strung, and occasionally suffered from hysteria.”

38

Although considered a wooden and untalented dancer by some, her lover, American expatriate modernist poet Ezra Pound (1885–1972), offered the following portrait in his “Dance Figure”:

Dark-eyed,

O woman of my dreams,

Ivory sandalled,

There is none like thee among the dancers,

None with swift feet.

39

This tragic doll of a woman appealed to both AC and Neuburg, and she got the job.

With Leila, Ethel, Gwen, Joan, and Vittoria always around, these students became known as “the Harem.” Crowley would work hard at his desk—on another issue of The Equinox

or one of his students’ books, such as The History of a Soul

and The Deuce and All

by Raffalovich, The Whirlpool

by Archer, or The Triumph of Pan

by Neuburg—while Joan stood behind him, running her fingers through his hair and calling him “Aleister,” even though everybody referred to him as AC. Except for the Mother of Heaven: with her accent, it sounded like “IC.” Her speech invariably prompted Crowley to declare, “Oh, Mother, I do wish you’d lose that accent. It sounds so bad in the Rites!” Although said in jest, it prompted Leila to ask Gwen for help with her dialect: “Will you tell me when I sy anything in Austreyelian?”

40

Occasionally the Vickybird, as Neuburg was dubbed, would look up from his desk and make some offhand pun about Archer’s sapphic tendencies, excusing himself with “If you’ll pardon the ostroloboguosity.” No week passed without Victor using this, his favorite word. Having had his say, he would return to business, reading page proofs or tossing coal onto the fire with his fingers. Both activities kept his fingers blackened, and when things got slow, Crowley would march over to his desk and paternally demand, “Victor, let me see your fingers.” In response, Neuburg would adopt a childlike posture, hiding his hands behind his back and replying, “Shan’t.”

And, when Neuburg commented how lucky Otter was to know Crowley as long as she had without being hurt, she shot back, “How could he hurt me? I’m

not in love with him, and I’ve never lent him money.”

The fourth Equinox

appeared that September, with its usual selection of fiction, poetry, and magic. Regarding Mathers v. Crowley

, the editorial claimed “Mathers has run away too—without paying our costs.” And, as prophetically as the clipping in the last issue, Crowley wrote, “I restrict my remarks; there may be some more fun coming.”

41

In order to induce religious ecstasy in its highest form Crowley proposes to hold a series of religious services; seven in number will be conducted by Aleister Crowley himself, assisted by other Neophytes of the A A

A , the

mystical society, one of whose Mahatmas is responsible for the foundation of THE EQUINOX.

42

, the

mystical society, one of whose Mahatmas is responsible for the foundation of THE EQUINOX.

42

The seven rituals, one for each of the planets in traditional astrology, would occur on consecutive Wednesdays from October 19 to November 30, 1910, at Caxton Hall. The doors would open at 8:30 and lock promptly at 9 o’clock, when the rites began. They would run for one and a half to two and a half hours. Attendees were encouraged to wear colors appropriate to the evening’s performance: black for Saturn, dark blue for Jupiter, red for Mars, and so on. One reporter complained that the rites “proscribe colours which are not in my wardrobe, although a few might be met by the choice of one of those ties which lie unworn at the back of every man’s chest of drawers.”

43

Admission to the entire series cost a hefty £5 5s., and only one hundred tickets were for sale.

Although the price of admission was high—about $200 by today’s standards—Crowley urged Probationers to attend in their robes and assist in the ceremonies. He also sent a complimentary ticket to H. G. Wells,

44

but there is no record of his attendance. Regardless, spectators packed Caxton Hall for the debut. Fuller even brought his mother.

All the participants—Crowley, Waddell, Raffalovich, Ward, Neuburg, and Hayes—were nervous because they had never rehearsed the rituals all together. Nevertheless, when they began by the dim glow of candles and colored lights, the rites came together. They explored and described the metaphysical aspects of the planets as magic and myth understood them. Dance, music, and poetry (mostly Crowley’s own) dressed up the ceremonial formalities.

Leila played from her violin repertoire, featuring numerous selections by the flamboyant Polish virtuoso Henryk Wieniawski (1835–1880). Her selections also included technically demanding works such as Paganini’s “Witches’ Dance,” Bach’s “Aria for G String,” and a polonaise by Vieuxtemps. The remaining pieces were romances and other popular salon music by Beethoven, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Saint-Saëns, and Wagner. She even salted a few original compositions among the classics.

The Rites of Eleusis generated considerable interest in the press, the Washington Post

reporting, “Meetings of the Rosicrucians for the purpose of conjuration and of invoking ‘forbidden knowledge’ have been secret until last week. Then the Eleusinian rites were performed openly in a London hall.”

45

However, reviewers widely panned the first performance—a grim portrayal of death and darkness—as everything from innocuous eccentricity to blasphemy. The Hawera and Normanby Star

(New Zealand) reported:

An atmosphere heavily charged with incense, some cheap stage effects, an infinity of poor reciting of good poetry, and some violin playing and dancing are the ingredients of the rite.… Positively the only relief in a dreary performance was afforded by a neophyte falling off his stool, which caused mild hilarity among a bored and uncomfortable audience.

46

The New York Times

wrote, “the hall was so dark that one might well call the Rites of Eleusis elusive.”

47

Closer to home, A Morning Leader

reviewer warned, “Unless a more cheerful tone is imparted … the people who have paid five guineas for the whole lot will have committed suicide before they reach Luna.”

The Penny Illustrated Paper

, however, articulated the fears of a staid and conservative society about Crowley:

There always has been about his writings and preachings an atmosphere of strange perfume, as if he was swaying a censer before the altar of some heathen goddess.

Not having been initiated, we cannot tell but Mr. Crowley’s Eleusinian rites do suggest an elusive form of Phallicism or sex worship.…

Unfortunately, this Eleusis business is not new. It has been done in Paris, entitled the Black Mass, on several occasions.

Far be it from us to suggest that the large-footed gentlemen from New Scotland Yard should visit Mr. Crowley’s little act … but the idea undermining the whole business is not healthy.

48

By the second rite, the yellow press attacked. The Looking Glass

ran “An Amazing Sect” on October 29; a cruel critique of the rites, it described the adepts’ robes as Turkish bath costumes and explained how the Mother of Heaven attempted acrobatics or jujitsu while standing on Crowley’s chest. John Bull

entered the fray on November 5 with its own attack. Not to be outdone, the Looking Glass

followed with “An Amazing Sect—No. 2” which pried luridly into Crowley’s shadowy past, printing misinformation about him such as his years as an art student, his mirror-covered temple in Boleskine, and his pseudonym Count Skerrett.

49

The attacks outraged Crowley’s circle, whose members urged him to sue. Unwilling to defend his lifestyle to a middle-class Edwardian jury, AC, much to his friends’ consternation, offered various excuses. “Suffer any wrong that may be done to you rather than seek redress at law,” he would say on one occasion. On another, he would quote a friend of his in city journalism (Radclyffe), who advised, “AC, let the fellow alone! If you touch pitch, you’ll be defiled.” Sometimes he didn’t want to stoop to his opponents’ level by acknowledging the attacks. Other times, he heard the Looking Glass

was in financial straits and could pay no damages. Or he was running out of money himself and couldn’t afford to sue. And there were always the vague “mystical reasons.” To defuse the situation, AC published a statement in two articles in the Bystander

. “On Blasphemy in General and the Rites of Eleusis in Particular” appeared the third week of November, defending himself against accusations leveled by the press. The autobiographical “My Wanderings in Search of the Absolute” followed, clarifying accounts of his past. Finally, he planned to publish the Rites in the sixth Equinox

for the public to judge for themselves.

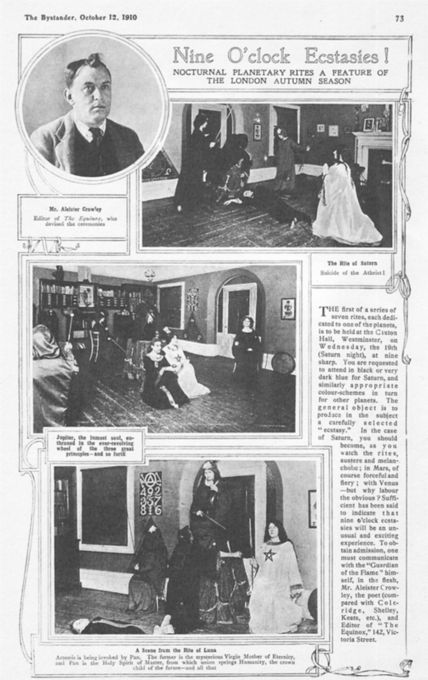

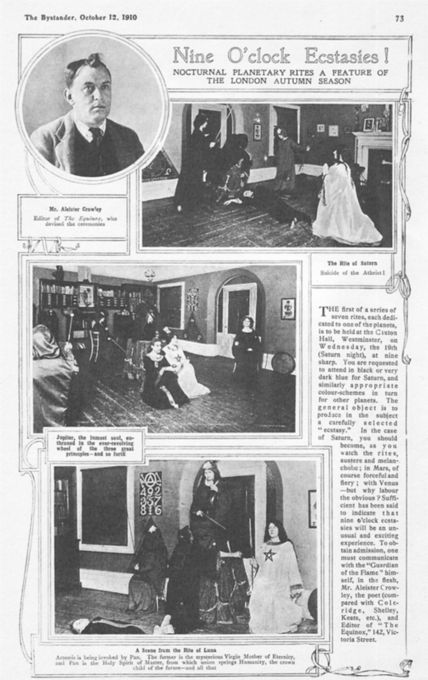

Newspaper photos of the Rite of Saturn (above) and the Rite of Jupiter (below). (photo credit 10.2)

Coverage from The Bystander

. (photo credit 10.3)

John Bull

contended that AC missed the point: at issue was not freedom of thought and expression but whether so notorious a person as he could espouse wholesome doctrines, and whether “young girls and married women should be allowed to go [to him] for ‘comfort’ and ‘meditation.’ ”

50

A third “Amazing Sect” installment followed in the November 26 Looking Glass

. As sensational and inaccurate as its predecessors, it extended its attack to Crowley’s friends. A section titled “By Their Friends Ye Shall Know Them” claimed:

Two of Crowley’s friends and introducers are still associated with him; one, the rascally sham Buddhist monk, Allan Bennett, whose imposture was shown up in “Truth” some years ago; the other a person of the name of George Cecil Jones, who was for some time employed at Basingstoke in metallurgy, but of late has had some sort of small merchant’s business in the City. Crowley and Bennett lived together, and there were rumours of unmentionable immoralities which were carried on under their roof.

51

Unlike Crowley, Jones contacted his solicitor, who wrote the publisher to demand a retraction and damages. The retraction appeared in the next issue, announcing that Jones was no longer associated with Crowley and congratulating him for breaking off with so disreputable a man. The paper felt no damage had been done, but offered him £5 for his trouble. The gesture insulted Jones, and he brought the matter to court.

Four days after this inflammatory passage appeared, the seventh and final rite, of Luna, closed the series at Caxton Hall. Coming full circle, it derived from the Rite of Artemis that started it all. Overall, the Rites were a theatrical landmark, anticipating by fifty years the experimental theater of the 1960s and 1970s.

52

The Rites’ first appreciation in academic writing on theater appeared in the 1975 article “Aleister Crowley’s Rites of Eleusis.” In it, Brown points out how innovative Crowley was in attempting to use theater’s sensory possibilities to alter consciousness.

53

Tupman’s 2003 dissertation argues that “Crowley’s Rites

were not merely a unique event with neither precedent nor subsequent influence.” Indeed, despite the fact that they are overlooked in every major Symbolist or avant-garde study, “the Rites

are a classic example of Symbolist theatre,” and were simultaneously forward-looking:

to include the audience as a part of the production foreshadowed the later work of theatre anthropologists and theorists such as Richard Schechner, and serves to illustrate one of the first attempts in the twentieth century to consciously create a psychological connection between theatrical and religious practice within the western hegemonic society.

54

Lingan’s survey of the theater in New Religious Movements also recognized The Rites of Eleusis

as an example of Symbolist theater.

55

Nevertheless, Crowley reflected on the event with disappointment: “I throw myself no bouquets about these Rites of Eleusis. I should have given more weeks to their preparation than I did minutes.”

56

Subscriptions barely covered costs, and the bad press caused attendance to dwindle so much that he

had to sell tickets to individual performances. Rather than draw flocks of recruits to the A A

A , it drove away members and alienated its cofounders.

, it drove away members and alienated its cofounders.

Fuller, fearing his name would surface in the papers next, refused to risk his military career by contributing to The Equinox

, and began to distance himself from Crowley. His decision would prove prescient, as a quarter century later the Imperial Fascist League’s paper, The Fascist

, would dig into Fuller’s past and run the headline: “Amazing Exposures of Mosley’s Lieutenant: General Fuller Initiated into Aleister Crowley’s (Beast 666) Occult Group.”

57

Fuller was outraged: during their association, Crowley was no more than a little erratic, and the “notorious” exploits of Crowley that The Fascist

described occurred after they’d parted ways. Fuller instructed his solicitor to prepare a writ for libel. While the publisher, Arnold Spencer Leese, maintains that the writ was dropped because “I had so much ammunition concerning him,”

58

the real reason was simple: upon reviewing Crowley’s more objectionable publications from 1907 to 1910, Fuller’s solicitor advised against the lawsuit. If The Fascist

continued its attacks, he reasoned, they could pursue a criminal, rather than civil, suit.

59

However, the headline did not have traction, and the subject matter quickly faded from sight.

Jones was even more displeased. He counted on Crowley’s support in his suit against the Looking Glass

. Instead, AC placed Archer and her husband in charge of The Equinox

and returned to Algiers with Neuburg for new Enochian workings. The disgruntled Jones wrote to Fuller, “Crowley goes to Algeria tomorrow. Some of his friends will say he ran away.” So too did his enemies. Crowley’s quiet departure signaled a victory for the tabloids, which proudly announced:

We understand that Mr. Aleister Crowley has left London for Russia. This should do much to mitigate the rigour of the St. Petersburg winter. We have to congratulate ourselves on having temporarily extinguished one of the most blasphemous and cold-blooded villains of modern times.

60

Crowley and Neuburg motored from Algiers to Bou-Sâada, then advanced with their interpreter, Mohammed ibn Rahman, on the 15th, trekking farther into the desert than on their last visit. Southeast of Ain Rich, despite the proverb “it never rains south of Sidi Aissa,” a torrential rainstorm caught and drenched them and their tents. Their guide refused to continue, so Crowley and Neuburg continued alone into the rain. When the rain let up on the third day, they attempted to pick up where their Enochian work left off: having scried into the thirty Aethyrs, they wished to continue with visions for the

eighteen Keys (another set of conjurations in Dee’s system). At the moment they began, however, Neuburg became ill, and they had to abandon the working. Crowley returned to London to conduct business, leaving Neuburg in Biskra to recuperate, feeling like Rose abandoned in China.

Crowley journeyed home with a fresh crop of ideas in his notebook, most of them inspired by desire for Leila Waddell. While still in Algiers, he wrote “On the Edge of the Desert,” “Return,” and “Prayer at Sunset.”

61

As he sailed, he finished “The Scorpion,”

62

a tragedy based on the 30th degree of Freemasonry; although it reflected Crowley’s idea to reformulate the Masonic rituals (as he would eventually do with OTO), Agatha—Leila’s A A

A motto—was one of its dedicatees. He also wrote “The Pilgrim”

63

for her and, during a layover in Paris’s Pantheon Tavern, penned “The Ordeal of Ida Pendragon,”

64

a short story whose title character combines traits of Leila Waddell, Kathleen Bruce, and a new acquaintance, Jane Chéron; hence the dedication “To I, J, and K,” i.e., I = Ida (Leila’s second name), J = Jane, and K = Kathleen.

motto—was one of its dedicatees. He also wrote “The Pilgrim”

63

for her and, during a layover in Paris’s Pantheon Tavern, penned “The Ordeal of Ida Pendragon,”

64

a short story whose title character combines traits of Leila Waddell, Kathleen Bruce, and a new acquaintance, Jane Chéron; hence the dedication “To I, J, and K,” i.e., I = Ida (Leila’s second name), J = Jane, and K = Kathleen.

During a layover in France, Crowley met Jane Chéron. Despite a French name, her features suggested Egyptian extraction. She was “a devotee of that great and terrible God” opium. Haidée Lamoureaux, The Diary of a Drug Fiend

’s heroin heroine, was based on her:

[She] was a brilliant brunette with a flashing smile and eyes with pupils like pin-points. She was a mass of charming contradictions. The nose and mouth suggested more than a trace of Semitic blood, but the wedge-shaped contour of her face betokened some very opposite strain.… Though her hair was luxuriant, the eyebrows were almost non-existent.… Her hands were deathly thin. There was something obscene in the crookedness of her fingers, which were covered with enormous rings of sapphires and diamonds.

65

She would also make a cameo in Moonchild

, when the narrator spends a Paris evening smoking opium with her. Although she had no interest in the occult, Chéron became Crowley’s mistress at odd intervals over the next sixteen years. Alas, while her “opium soul” inspired Crowley to write, her weakness meant years of addiction for her.

When Crowley finally reached Eastbourne, an expected cable from Leila did not arrive, so he wrote “The Electric Silence,”

66

a summary of his career; “The Earth,”

67

a short essay about Leila; and “Snowstorm,” a three-act play in which Leila, as the lead character Nerissa, expresses her lines through violin solos. Despite the disappointment of the cable, his love for Leila burned strong.

Finally reaching his London offices, Crowley was displeased with progress on the fifth Equinox

. In addition, Raffalovich had assumed leadership during AC’s absence, endorsing and cashing checks made out to Crowley and altering the content of advertisements. Reading the advertisement for 777

that incorrectly stated that less than one hundred copies remained for sale and that the price would soon rise to one guinea, AC was so furious that he forced Raffalovich to purchase enough copies of the book to reduce the stock to ninety.

Afterward, the pupil broke off relations with Crowley. Raffalovich would go on to write The History of a Soul

(1911), Hearts Adrift

(1912), and The Ukraine

(1914) and contribute to various magazines including the British Review, Vanity Fair

, and New Age

. In 1915 he would emigrate to the United States and work as a lecturer in French. From there, he lived in Italy for five years during the fascist regime as correspondent for British and American newspapers like the New York Times

and Chicago Tribune

.

68

This also gave him the opportunity to write Mussolini’s biography.

69

With a doctorate from the Ukrainian University in Prague, he would become professor of French and international politics, and French and Slavic history; in this capacity, he would serve on the faculties of Harvard, Dartmouth, and Emory. Dying in New Orleans in 1958 at age seventy-seven, he would leave five children and seven grandchildren.

70

Despite these setbacks, the fifth Equinox

appeared as scheduled in March 1911. To meet costs, its price increased from five to six shillings while its length decreased. Nevertheless, the magazine contained its usual rich variety. In addition to Crowley’s poems and essays, it also featured “The Training of the Mind” by Ananda Metteya (Allan Bennett),

71

“A Nocturne” by Neuburg, “The Vampire” by Ethel Archer, and as a special supplement, the record of Crowley and Neuburg’s Enochian vision quest, “The Vision and the Voice.”

His next book, The World’s Tragedy

(1910), also appeared around this time. Bearing the notice “Privately printed for circulation in free countries: Copies must not be imported into England or America,” the book is another swipe at convention. The text is an indictment of Christianity and its morals, while the preface provides an autobiographical sketch of AC’s Brethren upbringing. Pages XXVII and XXVIII of the preface—an unusual defense of sodomy that contained scandalous accusations about the morals of cabinet members and others in high power—were removed from all copies but those in the hands of his friends. Crowley, as usual, considered it his best work.

72

Finally, the April issue of the Occult Review

carried Crowley’s essay, “The Camel: A Discussion of the Value of ‘Interior Certainty.’ ”

73

Crowley sat in the courtroom, amused that neither side planned to call for his testimony. Fenton, he knew, was afraid of being exposed. Jones, meanwhile, he believed, feared what the notorious AC might say on the stand. To Fuller, however, Jones explained, “If, as my friend, he hasn’t the decency to come forward willingly, it would be an insult to myself had I compelled him to do so.”

75

The case opened with Simmons, for Jones, summarizing the charges, stating that the Looking Glass

printed so serious a libel about Jones “that if a tithe of it were true, my client was unfit to associate with human beings.” Because of his friendship with AC, he was linked to Crowley’s rumored immoralities. As a professional with a family to support, such statements were very damaging.

The proceedings were indeed unusual: although Jones and his past were briefly discussed—including his membership in the GD and his trusteeship on behalf of AC and Lola Zaza—the case quickly became a trial of Crowley’s morality. While AC’s failure to file suit with the Looking Glass

was considered telling, the most damning evidence came from Crowley’s own published works. Presented as evidence was “Ambrosii Magi Hortus Rosarum” from the collected Works

. Schiller had marked several of the Latin marginal notes: “Quid Umbratur In Mari.” “Adest Rosa Secreta Eros.” “Terrae Ultor Anima Terrae.” “Femina Rapta Inspirat Gaudium.” “Puella Urget Sophiam Sodalibus.” “Culpa Urbium Nota Terrae.” “Pater Iubet Scientiam Scribe.” The words formed by their initials—quim, arse, tuat (twat), and so on—were Crowleyan mischief that none of his associates had discovered up to that point.

Despite objections from Jones’s counsel that Crowley’s writings were irrelevant to the question of Jones’s character, the defense revolved around a simple premise: the Looking Glass

did nothing more than say Jones was an associate of Crowley. Any libelous meaning coming from such a statement was due to Crowley’s notoriously evil character and not anything written by the paper.

Next was the subject of Allan Bennett recently being attacked in the paper Truth

, and his failure—like Crowley—to file suit. The fact that Bennett, as a monk, had no possessions and was living five thousand miles away didn’t seem to matter. Nor did Bennett’s medicinal use of drugs help matters. In the end, the legal inaction of Crowley and Bennett was seen as admission of guilt.

Finally, Schiller introduced surprise witnesses for the defense: Mathers, the wizened patriarch of the GD, was introduced to the court as Mr. Samuel Sidney Liddell MacGregor, ready to return the favor to Crowley for his defeat in court. The other was Mathers loyalist Dr. Berridge. Mathers fielded questions about the secret Rosicrucian Order, Crowley’s expulsion from the GD, previous incarnations and various pseudonyms attributed to either him or Crowley, and other mystical traditions. At one point, Justice Scrutton interjected, “This trial is getting very much like the trial in Alice in Wonderland

.” Berridge, meanwhile, recounted the rumors of “unnatural vice” that had circulated about Crowley during his GD years.

Fuller was the only witness called in Jones’s defense and could do little to undo the damage done by the previous testimony. The court transcript—while an interesting read—is too extensive to reproduce here.

76

Schiller’s closing comments to the jury, however, captures its gist:

You have heard from Dr. Berridge the type of man Aleister Crowley is. Confessedly Crowley stands as a man about whom no words of condemnation

can be strong enough. That is the man of whose friendship Captain Fuller is proud; that is the man whose associate Mr. Jones is. I submit I have proved to you up to the hilt both by his writing and his own confessions that Crowley is a man of notoriously evil character. If that be so, gentlemen, I have discharged the chief burden on my shoulders, and it only remains for you to say whether I have gone beyond the bounds of fair comment.

Gentlemen, was not the paper justified in showing up this amazing sect of Crowley’s and were not they right in saying and fully justified in the comment they made about Mr. Jones’s association with Aleister Crowley? Though he knew these rumours were flying about, rumours which Crowley did not dare to deny, he still associated with Crowley and would have you believe that he is a man of perfectly unblemished character, a man whom he would not hesitate to introduce to his own wife. If a man values his own reputation so cheaply that he does not mind associating with that kind of creature, he must not complain if comment is made about it and he must not come to you and ask you to give him exemplary damages. When he can associate with a creature of Aleister Crowley’s description and can come here and be proud of it, and to corroborate him, call a friend who is proud of the friendship of a man who writes the kind of stuff you have seen, a man who does not hesitate to advertise his pernicious literature of a gross type by appealing to the worst instincts of degenerates amongst mankind, by appealing to their sense of the morbid, a man who himself publishes the criticisms of his books in order to attract purchasers for his wretched books, books that have been criticized in a well-known publication of one of the two leading universities as dealing with a revolting subject revoltingly handled, and who advertises the whole thing under the hypocritical guise of a society for the propagation of religious truth—what are you to say of a man who boasts of his associations with such a creature?

I ask you to say as twelve healthy-minded men that there is no comment strong enough which a paper is not entitled to make in criticizing the conduct of a man like the plaintiff in this case. It serves him right if he meets with strong criticism under such circumstances. Were we not justified in saying that you must judge this man’s character by his association with this creature? Gentlemen, I ask you to say, and I ask you with confidence to say, that I have not and that I was amply justified in making the comment I did make, that it was a fair and proper comment to make under the circumstances, and I ask you therefore to give a verdict for my clients.

Scrutton posed four questions to the jury: 1. Were the words complained of defamatory of the plaintiff? 2. If so, were the defamatory statements of fact substantially true? 3. Were the defamatory statements so far as they consisted of opinion fair comment on facts? 4. What damage has the publication caused the plaintiff? After thirty-two minutes of deliberation, the jury returned its verdict. They answered the first three questions “Yes,” and the last “None.” In essence, the statements and their unsavory implications were accurate and fair comment on a friend of Crowley’s, and Jones thereby suffered no damages. They entered judgment for the defendants. The Looking Glass

had won.

Jones’s defeat unleashed a new wave of gossip about the notoriously evil Aleister Crowley. When American art patron and book collector John Quinn (1870–1924) visited publisher Elkin Matthews at this time, the subject of Crowley inevitably came up. Matthews had published Ambergris

, and told Quinn, “We had a very ’ard time getting him to cut things out of it. Right now, Crowley’s out of England because of something he’s done.” “What was the trouble?” Quinn asked.

“We don’t know, sir, only he has got himself dreadfully talked about.”

77

The worst ramifications, however, were personal. Because Crowley offered no assistance, Jones ended their friendship. Although he would continue to oversee Lola Zaza’s trust for decades, he maintained distance from Crowley. He would retire in 1939 because of wartime restrictions on trade; his planning would prove insightful, as an air raid would destroy his lab in 1941.

Fuller, whom Crowley considered his best friend, sent his last letter ever to Crowley on May 2. He thought Crowley a coward for not defending himself and broke with him on the same grounds as Jones. Fuller would go on to attain the rank of major-general and invent the blitzkrieg, which England would disregard and Germany would adopt. He would be the only Englishman invited to Hitler’s birthday party in 1939. Throughout the years, however, his interest in magic would never fade: he would write books like Yoga

(1925) and Secret Wisdom of the Qabalah

(1937), and contribute articles to journals like Form

and the Occult Review

.

78

Even in his last days, Fuller maintained that Crowley was one of England’s greatest lyric poets.

79

At this time, Ward also became disillusioned with the A A

A . He not only doubted Crowley’s honesty and character but also grew weary and critical of magic. Feeling a need to break away, he welcomed the opportunity to become professor of mathematics and physics at Rangoon College, where he would study Buddhism. His thoughts on the subject remained remarkably close to Crowley’s: “Properly speaking, the ‘theory’ is philosophy, the ‘practice’ is science; and both together are religion,” he would say. In the end, he would become a Christian Scientist.

. He not only doubted Crowley’s honesty and character but also grew weary and critical of magic. Feeling a need to break away, he welcomed the opportunity to become professor of mathematics and physics at Rangoon College, where he would study Buddhism. His thoughts on the subject remained remarkably close to Crowley’s: “Properly speaking, the ‘theory’ is philosophy, the ‘practice’ is science; and both together are religion,” he would say. In the end, he would become a Christian Scientist.

Thus, in very short order, Crowley lost two of his oldest friends and, with Ward and Raffalovich, two of his best students. Two-thirds of the founding triad of the A A

A had seceded, leaving him, like Mathers, sole authority of his occult organization, and bad press caused A

had seceded, leaving him, like Mathers, sole authority of his occult organization, and bad press caused A A

A enrollment to dwindle to only three applicants for the year 1911.

enrollment to dwindle to only three applicants for the year 1911.

The Secret Chiefs were testing him, he decided, and help would soon be on its way.

A lone star shone overhead, the moon set behind a tower, and he thought, I am alone in the Abyss

. It felt as if he were again experiencing that soul-crushing ordeal. Crowley returned to his room and wrote “The Sevenfold Sacrament,”

80

a pendant to “Aha!” describing that evening’s Abyss reprise.

Adversity, however, always inspired Crowley; this time, he entered an annum mirabilis

. With Fuller gone, Crowley prepared to fill The Equinox

with his own works, writing feverishly throughout his stay in Paris and Montigny-sur-Loing. The English Review

’s June publication of “On the Edge of the Desert” served as the starting gun for his marathon.

On August 10, spending Leila’s birthday separated from his love, Crowley dwelt all night on their year together. “A Birthday” resulted, recalling their meeting, her last birthday, the Rites of Eleusis, a tentative parting and reunion, their arrival in Paris. On their present separation, he wrote:

Do not then dream this night has been a loss!

All night I have hung, a god, upon the cross;

All night I have offered incense at the shrine;

All night you have been unutterably mine …

Crowley wrote many other pieces at this time, including two short stories: “The Woodcutter,” about a man with a one-track mind, and “His Secret Sin,” about sexual hypocrisy. Mortadello

,

81

his five-act play of Venice, also came out of this period. Rhythm

gave it a decidedly mixed review, calling it

a dull, stupid, dreary affair. The stale situations, the childish “comedy,” and the peurile grossness, are incredibly school-boyish; though the verse in which the play is written is damnably accomplished. Mr. Crowley manipulates his medium with a deadly dexterity. He works the Alexandrine for all it is worth; and gets unexpected amusement out of it by the skillful surprise of unexpected internal rhymes. He is a master of metrical artifice.

82

Nevertheless, Mortadello

would remain one of his favorite pieces, which he would try throughout his life to produce on the stage.

He got the idea for his play “Adonis” next, and stopped at the Café Dôme in Montparnasse for a citron pressé

before commencing. New inspiration struck unexpectedly when, to his bemusement, he saw Nina Olivier with her latest attachment, Scottish pianist and raconteur James Hener Skene (born c. 1878).

83

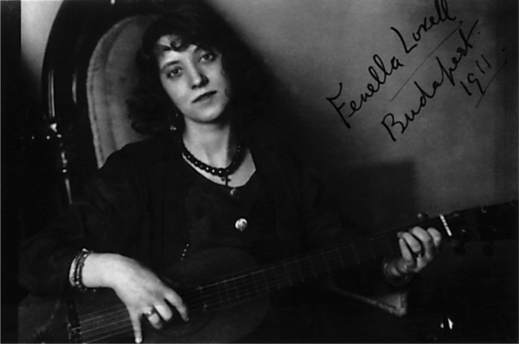

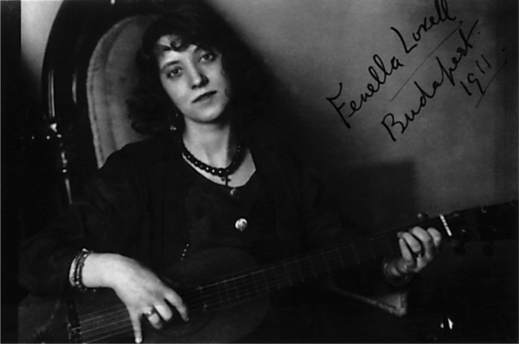

Accompanying them was Fenella Lovell, a consumptive-looking Parisian model of 203 Boulevard Raspail. Of Romany descent, she wrote Gypsy songs in English and Romany, and was involved in the Gypsy Lore Society.

84

In the summer of 1908 she gave Romany language lessons to British poet Arthur Symons (1865–1945), who offered her hospitality and found her to be an accomplished teacher.

85

She also modeled for many, including aspiring Welsh

painter Gwen John (1876–1939), whose younger brother Augustus John (1878–1961) would become better known. Of Lovell, Gwen John wrote, “no one will want to buy her portrait do you think so? … it is a great strain doing Fenella. It is a pretty little face but she is dreadful

.”

86

Her beauty and dress struck Crowley, who mentally cast her as the heroine of some yet-unwritten play. Eyeing her, he wrote in his head:

By the window stands Fenella, fantastically dressed in red, yellow, and blue, her black hair wreathed with flowers. She is slight, thin, with very short skirts, her spider legs encased in pale blue stockings. Her golden shoes with their exaggerated heels have paste puckles. In her pale face her round black eyes blaze. She is rouged and powdered; her thin lips are painted heavily. Her shoulder-bones stare from her low-necked dress, and a diamond dog-collar clasps her shining throat. She is about seventeen years old.

87

Yes, he mused, and left minutes later. Returning to his room at 50 rue Vavin, he wrote “The Ghouls,” then proceeded immediately on to “Adonis.” He completed both in a single forty-three-hour sitting.

Fenella Lovell. (photo credit 10.4)

While most of these stories appeared in the next two issues of The Equinox

,

88

the bulk of his work that summer involved the magical papers of the A A

A , which he wrote in abundance. These documents he divided into four classes: Class A documents were Holy Books, “inspired” or “channeled” works not to be altered in any way; Class B documents were scholarship; Class C were inspirational or suggestive; and Class D were practical instructions.

, which he wrote in abundance. These documents he divided into four classes: Class A documents were Holy Books, “inspired” or “channeled” works not to be altered in any way; Class B documents were scholarship; Class C were inspirational or suggestive; and Class D were practical instructions.

While most of the Thelemic Holy Books were channeled at the end of 1907, the remaining ones came to Crowley this summer. These Class A documents

included: “Liber B vel Magi” (The Book of the Magus), which describes the grade of Magus 9°=2°; “Liber Tzaddi vel Hamus Hermeticus” (The Book of the Hermetic Fish Hook), which calls mankind to initiation; “Liber Cheth vel Vallum Abiegni” (The Book of the Wall of Abiegnus, the great Rosicrucian mountain), which describes crossing the Abyss; and “Liber A’ash vel Capricorni Pneumatici” (The Book of Creation, or the Goat of the Spirit), an instruction in sexual magic in veiled language.

89

Class B documents written at this time include “Liber Israfel,” an invocation of the Egyptian god Thoth written by Allan Bennett and revised by Crowley; “Liber Viarum Viae” (The Way of Ways) on the tarot; “Liber Viae Memoriae vel ThIShARB” (The Way of Memory), a method for thinking backwards to understand the causes acting in one’s life; and a tentative work on the Greek kabbalah.

90

Class C, or suggestive, works include “Across the Gulf,” an allegorical account of a past life in Egypt; and “Liber Os Abysmi vel Daath” (The Book of the Mouth of the Abyss), which describes a method of entering the Abyss based upon logical skepticism. “Adonis” he also classed in this category.

The Class D, or official instructions, included the following: “Liber NV” and “Liber HAD” describe, based on the Book of the Law

, how to attain the states of consciousness associated with these Egyptian deities. Practical instructions in yoga were summed up in books on meditation (“Liber Turris vel Domus Dei”), devotion (“Liber Astarte vel Liber Berylli”), and pranayama (“Liber RV vel Spiritus”). “Liber IOD” (The Book of Vesta) contains instructions on thought reduction, while “Liber Resh vel Helios” (The Book of the Sun) contains adorations of the sun for dawn, noon, sunset and midnight.

91

This last exercise Crowley considered most important for reminding students of the Great Work, and Crowley practiced it regularly throughout his life.

On the autumnal equinox, the sixth issue of The Equinox

appeared. Owing to difficulties with Fuller and Raffalovich, it was the slimmest volume to date, and notably missing was the next installment of “The Temple of Solomon the King.” To compensate, Crowley printed “The Rites of Eleusis” as a supplement for the public to judge its contents. Besides several A A

A libri

, this issue also featured contributions from Archer and Neuburg as well as book reviews courtesy of two of his friends, chemist Edward Whineray and Freemason John Yarker. Yarker was a new acquaintance who would go on to influence Crowley’s magick heavily. Yarker had previously awarded Crowley with various Masonic and pseudo-Masonic distinctions after his victory in court against Mathers over the GD rituals reproduced in The Equinox

. AC had since reviewed Yarker’s The Arcane Schools

in the fourth Equinox

, writing “The reader of this treatise is at first overwhelmed by the immensity of Brother Yarker’s erudition” to which the author replied with a letter of thanks for “your kindly review.”

92

libri

, this issue also featured contributions from Archer and Neuburg as well as book reviews courtesy of two of his friends, chemist Edward Whineray and Freemason John Yarker. Yarker was a new acquaintance who would go on to influence Crowley’s magick heavily. Yarker had previously awarded Crowley with various Masonic and pseudo-Masonic distinctions after his victory in court against Mathers over the GD rituals reproduced in The Equinox

. AC had since reviewed Yarker’s The Arcane Schools

in the fourth Equinox

, writing “The reader of this treatise is at first overwhelmed by the immensity of Brother Yarker’s erudition” to which the author replied with a letter of thanks for “your kindly review.”

92

Sweet classical melodies issued from the piano; facile fingers deftly executed the performance; and silence greeted its conclusion. Hener Skene turned from the piano to face the man who had requested a lesson in music appreciation. “That

was Chopin.”

“I don’t know,” Crowley remarked, desperately hiding a smile. “I think it a trifle boring.”

“Oh?” Skene lifted an eyebrow. “Then how about this?” He returned to the piano and played another piece. It was a selection from Cavalleria Rusticana

(1890), the one-act opera by Pietro Mascagni (1863–1945) about a love triangle ending in bloodshed. Skene considered it a clearly inferior work.

Crowley applauded. “Much better! This

music moves me.”

The music stopped. Skene again turned to face Crowley, who quickly replaced the smirk on his face with an inquisitive expression. “No, no,” the pianist objected. “You should prefer Chopin. Let’s try again.” He returned to the piano and began another piece by the Pole.

A smile returned to Crowley’s lips, and he began thinking he had judged Skene too hastily. When Crowley’s fiancée, Eileen Gray, first introduced them in Paris in 1902, Skene came off so witless and conceited that Crowley parodied him in the appendix to The Star and the Garter

.

93

Meeting him at the Dôme for only the second time, he found Skene so unpleasant and cadaverous that he helped inspire “The Ghouls.”

94

When Skene shifted his affections from Nina to dancer Isadora Duncan, to whom he was accompanist, he had “the manners of an undertaker gone mad, the morals of a stool-pigeon, and imagining himself a bishop.”

95

Despite all that, Crowley saw Skene as a potential source of fun.

Chopin’s piece ended, and Skene looked again at Crowley, who wore a pensive, almost pained, scowl. “I—I think

I understand,” AC stammered.

“Again!” Skene declared, and returned to the ivories for more Mascagni.

Crowley was so delighted he was loathe to release the moment. Then he devised a way to milk the game even further. When Skene again finished, Crowley feigned rapture. “Yes, yes, I see! If you would be so kind, I’d like you to repeat this lesson for my good friend, Princess Bathurst.” Princess Leila Ida Nerissa Bathurst Waddell.

Standing at five-foot-five, Mary Desti (1871–1931) was a voluptuous, big-boned woman with curly black hair and attractive—even magnificent—Irish-Italian features. Born in Quebec and raised in Chicago, she moved to Paris and adopted Duncan’s penchant for wearing only sandals and a Greek tunic held together by a pin at her shoulder; indeed, Desti gained some notoriety when her landlord attempted to evict her for dressing too scantily.

97

She was a passionate, worldly woman, and her personality and magnetism attracted Crowley straight off. She felt the same profound emotion toward him. He spent the evening sitting cross-legged on the floor, “exchanging electricity with her.”

98

Mary Desti (1871–1931) in 1916, by E. O. Hoppé. (photo credit 10.5)

Mary Dempsey, to use her legal name,

99

had been married four times. Little is known of her first marriage. Her second husband, Edmund P. Biden, was a heavy-drinking traveling salesman whose banjo playing taught her to despise the instrument. The birth of their son Edmund Preston on August 29, 1898, came as a complete surprise; both were apparently naive about the facts of life. Up to the last minute, Biden believed his wife had a tumor. Their marriage ended in January when Mary, fed up with Biden’s drunken rages, escaped with her infant to France. Reflecting on two wasted years, she detested her ex so much that she could not speak his name. Named after his father, her boy thereby went by his middle name, Preston.

While apartment-hunting in Paris, Mary met Mrs. Duncan, who took her home to meet her daughter, Isadora. The two became close friends, and Mary moved into Isadora’s Paris studio while Mrs. Duncan took charge of Preston. Mary idolized Isadora, seeing in her the person she wanted to be.

Mary wed for a third time in Memphis, Tennessee, on October 2, 1901. Her new husband was childhood sweetheart Solomon Sturges, grandson of the pioneering financier who founded Solomon Sturges and Sons, later known as the Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company of Chicago. Sturges adopted Mary’s son, and the new family was close and happy. Mary wrote a play called “The Freedom of the Soul,” which had a single performance at Chicago’s Ravina Park; of his wife’s penchant for writing, Sturges remarked “it was infinitely to be preferred to bridge whist playing, and it wasn’t so hard on a man’s pocketbook.”

100

After Paris, however, Chicago stifled Mary, and not even the wishes of her husband would keep her from Isadora. The marriage became strained when Mary followed the notorious dancer across Europe. Tolerant at first, Sturges eventually tired of his wife’s dress and constant flitting across the Atlantic. After a terrible argument in 1907, they separated, and Mary later returned to Europe. Sending Preston to a Parisian boarding school, she was free to live an unconventional, liberated life. Solomon Sturges was eventually granted a divorce for desertion in January 1911.

Her fourth and unfortunate marriage would occur in London the following year—on February 12, 1912—to Turkish fortune hunter Vely Bey.

101

They had met years ago in Chicago, where Bey had been trying (ultimately unsuccessfully) to launch a Turkish tobacco import company. This husband liked how she dressed, and as a bonus his father was Ilias Pasha, court physician to the sultan of Turkey.

102

Both mistakenly thought the other was wealthy, and only after the wedding did the economic truth come out. This, combined with Bey’s dislike of Preston, doomed the marriage from the start. Before things blew up, Mary learned the formula for the lotion her father-in-law had concocted to cure a rash on her face; it was supposedly common throughout the harems of Turkey, and it not only cleared up her rash but also smoothed away wrinkles. Seeing a lucrative opportunity, Mary marketed it as “Le Secret du Harem,” and founded at 4 rue de la Paix her renowned perfumery “Maison d’Este.” This name derived from Mary’s dislike of her given surname, Dempsey; some amateur genealogy linked Dempsey to Desmond and d’Este, which she adopted. However, the d’Este family in Paris threatened to sue if she did not change the name of her salon and remove the garish neon sign out front. Hence the salon became “Maison Desti.”

Encountering the free spirit of future entrepreneur Mary d’Este or Mary Desti, Crowley couldn’t help feel she was a perfect match for him. Suddenly he found himself torn between his unshakable affection for Leila and the inexplicable feeling he got from this stranger.

“Preliminary skirmishing” characterized the following months as Crowley tried to make her acquaintance. Two days after the party, he met her for tea and tried to explain the feeling he got when they met. Unsurprisingly, she knew nothing of magic, but having written some plays, shared his literary aspirations. They dined the next evening, and after a snack of chocolate and rolls, Crowley left for northern England.

He must have come on too strongly, for she answered none of the letters he sent over the next two weeks.

Out with the old, in with the new.

On October 29, Crowley sought Mary Desti at the Savoy, prepared to bury her in barbed words the way only a great poet could. How dare she ignore his letters! But his armor melted at the first sight of her, and he forgave all.

In November—even though he was hard at work on the next Equinox

, which would include The Book of the Law

and an account of its reception—AC and Mary set out on a vacation to one of his favorite spots: St. Moritz. They

spent November 18 at Montparnasse, leaving Paris the next evening. As they traveled, Crowley studied his 1904 notebooks, The Equinox

page proofs, and the manuscript of The Book of the Law

. On the night of November 20, Mary dreamed she saw the heads of five old men called the White Brothers telling her, “It’s all right.” She didn’t know what it meant, and, when she told AC, he showed no interest. It wasn’t her mind that he wanted to get inside.

Weary from travel, they spent the night of November 21 at Zurich’s National Hotel. “This town is so hideous and depressing that we felt our only chance of living through the night was to get superbly drunk,”

108

Crowley wrote. More drinks followed; then they had sex. As a lover, Crowley was magnetic and experienced; Mary was no less so, carrying on like an amorous but infuriated lioness.

As they rested in bed, exhausted but unsatiated, Mary slipped into a calm, relaxed state and began talking about the old white-bearded man from her dream. She said he held a wand in his hand, and on his hand was a ring with a feather in its glass. A large claw was on his breast.

Overstimulated, Crowley surmised. The combination of alcohol and sex was too much for her. As she continued, however, Crowley realized she was not recounting her dream of the previous night but was describing this old man as she saw him right now. It reminded him of Rose’s strange, dazed condition when she contacted the Chiefs.

He sat upright and instructed her, “Make yourself perfectly passive. Let him communicate freely. What do you see?”

The five white brethren turned red, she said, and spoke: “Here is a book to be given to Frater P.” Crowley nearly fell over with surprise: Mary did not know his magical name. “The name of the book is Aba

,” she continued, “and its number is four.”

Crowley computed the values of the letters a, b

, and a

and came up with four. This was more knowledge she did not possess. So far, so good. Mary went on to describe a swarthy man named Jezel, who was hunting for the book. However, the elder commented, Frater P. would get it.

Suddenly, the vision became unclear, and Mary grew frightened. She didn’t understand what this was all about. Crowley encouraged her to continue. “What’s his name?” he asked.

Abuldiz, she replied.

“What about seventy-eight?” AC asked, giving a number of Aiwass.

“He says he is

seventy-eight.”

“What is sixty-five?” he tested again, giving the number of Adonai

, the general godname for the holy guardian angel.

“Frater P is sixty-five, and his age is 1,400.” Pure gibberish, he thought.

“What of Krasota?” he asked about the Word of the Equinox. Abuldiz the wizard only frowned in reply. Crowley was dissatisfied, and remained skeptical even though Abuldiz insisted Crowley show faith. Through Mary, Abuldiz

promised to clear everything up in a week, at precisely 11 p.m. He instructed Crowley, at that time, to invoke as he did in Cairo in 1904.

An odd coincidence, he mused, as the rituals he used with Rose in 1904 were again in his possession as he prepared to publish The Book of the Law

. Furthermore, he just happened to have with him all the necessary ritual implements, including the robe he wore at the Cairo Working in 1904. Mary had even packed a blue and gold abbai like Rose’s. Arriving at St. Moritz the next day, their suite at the Palace Hotel contained a tall mirror very much like the one in his honeymoon suite in Cairo. This impending publication of The Book of the Law

, he assumed, was causing a magical stir.

In the following days, Crowley told Mary everything he knew about magic. This way, he ensured that Abuldiz could only convince him of his authenticity by revealing something neither of them knew; it would have to be big. “Anything she said three times she believed fervently,” her son attested to Mary’s imagination. “Often twice was enough.”

109

Coming from an intellect like Crowley’s, the words opened a new dimension of reality that she accepted wholeheartedly. She found this business of magic fascinating.

On November 28 they prepared for the ceremony as instructed. They stowed all unnecessary furniture. Five chairs sat out for the five brethren. An octagonal table served as the altar, holding the magical weapons, invocations, and incense. Mary, wearing her abbai with rich jewels as described in The Book of the Law

,

110

sat on the floor facing the mirror in the east. Dressed in his usual robes, Crowley kindled the incense and performed the Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram at 10:38 p.m. By 10:45, he began reciting the Augoeides vigorously. At the stroke of eleven, he uttered, “Cujus nomen est Nemo, Frater A

A

A

, adest.”

(I am he whose name is Nemo, a Brother of the A

, adest.”

(I am he whose name is Nemo, a Brother of the A A

A .)

.)

“He’s here,” Mary replied solemnly. “He wants to know what you want.”

“Nothing!” he snapped. “Did I call him, or he me?”

“He called you … but there is seventy-seven.”

That was Leila’s number, and Crowley momentarily remembered his lover in London. Then, returning to the present, he asked, “Why did you call me?”

“He says, ‘To give you this book.’ ”

“How will it be given?”

“He says, ‘By the seer.’ But I don’t have any book!”

“Do you claim to be a Brother of the A A

A ?”

?”

“He has A A

A in black letters on his breast.”

in black letters on his breast.”

“What does A A

A mean?”

mean?”

With this test, the vision became garbled. She saw images and symbols, numbers that meant little to either of them.

“Ask him to be slower and simpler,” Crowley finally insisted. “Give further signs of your identity: Are you Sapiens Dominabitur Astris?” This was the motto of the GD’s German contact, Fraulein Sprengel.

“I see nothing but a skull,” Mary replied.

Good

, Crowley thought to himself: Sprengel is dead

. “Is Deo Duce Comite Ferro one of you?” He dragged Mathers into it.

“No. No longer,” she replied as Abuldiz. After a few more questions, Mary began to complain of someone beside her, breathing on her. Looking about, Crowley could see small elementals bounding about the room.

“Ask who breathes,” he instructed.

“The black man,” she replied. “He has now a white turban.” Using a technique Crowley had taught her, she banished the figure away. More garbled communication followed, with Abuldiz finally stating, “Ask me about nine.”

Crowley raised an eyebrow. “Consider yourself asked.”

“Nine is the number of a page in a book.”

“We have none in stock. What book?”

“A book of fools.” Only in later years would this make sense to Crowley, referring to his authorship of The Book of Wisdom of Folly

after he assumed the grade of Magus (9°=2°). The communication went off on another apparent tangent. After a futile exchange, Mary announced, “He shows another book with a blazing sun, and covers in gold. He says, ‘The Book IV. Your instruction to the Brothers.’ ”

“Then I’m not to publish it?”

“Abuldiz gives the sign of silence.”

He nodded. “I understand by that that I am not to publish it.”

“Never. But you are to find it.”

When more gibberish followed, Crowley lost his patience. “Does he wish to go on with this very unsatisfactory conversation?”

Mary, as Abuldiz, replied, “Go to London, find Book IV, and return it to the Brothers.”

“Where is Book IV?”

“In London. When you get Book IV, you’ll know what the white feather means. Obey and return Book IV to the Brothers.” By this time, after over nearly an hour, Mary complained she was tired.

Crowley agreed. “Ask for another appointment.”

Abuldiz replied, “The fourth of December, between 7 and 9 p.m.”

Fine. “Good-bye!”

Further communications with Abuldiz occurred on December 10, 11, 13, and 19. In all but the last instance, the communication began with champagne, sex, and incantations. They gradually came to the understanding that they

needed to go on a retirement and write Book IV themselves. During the last communication, at Milan, Crowley received the final details.

By this time, Crowley asked questions in acronym form to further test the wizard. “N.w.a.t.V.?” Now what about the villa?

Abuldiz replied, “What you will. Patience; there is danger of health.”

“H.o.f.?” Here or further?

“No. You asked wrongly.”

“H?” Here?

“W?” Where? “R?” Rome?

“No.”

“N?” Naples?

“Yes.”

“Is Virakam to work herself, or only to help Perdurabo?”

“Virakam is to work, to serve.” This was appropriate, as Abuldiz had previously told them the word meant “I serve the light.” “Tomorrow you will find what you seek; you will know, for he will be with you and give you the sign. Don’t hesitate and don’t worry, bring forth the fruit. Till tomorrow.”

“Good-bye!”

“There is no good-bye. There’s work to be done; I’m always ready. Don’t struggle. Accept and believe.” He held a finger to his eye, and was gone.

Crowley now understood: he and Mary were to travel past Rome and rent a villa. When Abuldiz told Crowley how to recognize the Villa—“You will recognize it beyond the possibility of doubt or error”—he had a vision of a villa on a hillside, with a garden and two Persian nut trees in the yard. There they would write Book IV, a text of practical magic.

They left for Rome the next day.

111

As instructed, they moved past Rome after two or three days, combing the Naples countryside for a place matching Abuldiz’s description. They expected to find dozens of suitable villas, but were sadly disappointed: after days motoring through the city and suburbs, they failed to find a single match. The villa became an obsession. They discussed it while driving and eating, and one night Mary even dreamed of it.