Crowley returned to his war-ravaged homeland just before Christmas, finding merrie olde England much like he remembered it: cold, damp and dreary. It was only the first misery he would find awaiting him. Having no place to live, he stayed with his aunt at the same Eton Lodge abode that he, in The Fatherland , had challenged Count Zeppelin to level. As he wrote at the time, “Not only has the war changed nothing in this house of my aunt’s where I have roosted, but they haven’t altered the position of a piece of furniture since Queen Victoria came to the throne.” 1

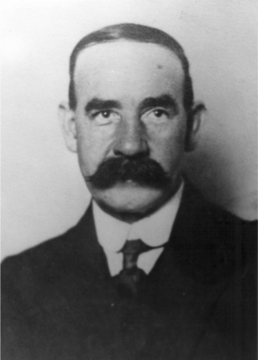

When the weather flared his chronic bronchitis into asthma, Crowley turned to his physician since 1898, Harold Batty Shaw (1866–1936), a specialist in consumption and chest diseases. A man of abnormal energy and strong opinions, Shaw was educated at Yorkshire College, Leeds, and University College, London. He gave the 1896 Goulstonian Lectures before the Royal College of Physicians a year before earning his MD degree and two years before joining the Royal College’s ranks. His students at University College and Brompton Hospital found a dogmatic and precise teacher in him. His most famous patient was arguably Indian mathematical genius Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887–1920). 2 For Crowley, Shaw prescribed a common analgesic: heroin. 3 Despite his physician’s credentials, Crowley became dependent on what was then a legal if not efficacious drug. Alas, passage of the British Dangerous Drug Act in 1921 would leave Crowley in a predicament, as will be seen later.

For now, he was destitute. The money and possessions he had put into storage before the war had vanished: doubtlessly, he believed, at the hands of Cowie and Waddell. Although Crowley inherited £3,000 on his mother’s death, the provisions of his divorce settlement earmarked the money for a trust fund to be split between himself and his daughter, Lola Zaza.

When Crowley checked to see how his old friend Oscar Eckenstein had fared since the war had interrupted their planned attempt on Kangchenjunga, he found him a stodgy married man, and never saw him again. While AC’s disappointment is thinly veiled, the inescapable truth is that Eckenstein was sixty-one years old at this point, to Crowley’s forty-four. Furthermore, in the years since their 1902 expedition, Eckenstein had remained far more active in the sport than Crowley: he continued climbing until at least 1912, when he was fifty-three. In 1908 he redesigned the crampon into the prototype from which modern designs derive; he invented an innovative short ice-ax; and he published technical articles on knot-tying and on the use of nails on climbing boots. 4 Eckenstein died of consumption shortly thereafter in 1921.

The final straw was the yellow press rolling out the welcome mat in its inimitable style. John Bull greeted Crowley with the headline:

Another Traitor Trounced

Career and Condemnation of the Notorious Aleister Crowley

The article read, “We await an assurance from the Home Office or the Foreign Office that steps are being taken to arrest the renegade or to prevent his infamous feet ever again polluting our shores.” 5 Although the attack upset Crowley, he followed the I Ching’s advice to do nothing. Fortunately, Commodore Gaunt interceded to advise authorities against taking action. Thus, while public opinion of Crowley remained low, nothing came of the outcry.

Knowing there had to be something better than this, feeling himself caught up in a new magical current, he wired Leah to meet him in Paris. She arrived eight months pregnant and with Hansi in tow. On January 11, a year after Leah first became the Scarlet Woman, they swore to build an Abbey of Thelema.

At this time, Leah described to AC how, on the boat from America, she befriended a French woman, Augustine Louise Hélène Fraux Shumway, nicknamed Ninette (1894–1990). Born in Decazeville, France, on June 9, 1894, she had lived in the United States since 1911, marrying American Howard C. Shumway in 1915, who died in an automobile accident before their son, Howard, was born in Boston on July 17, 1916. Ninette found work as a nursery governess, but with no family to help support her, she decided to leave Concord, Massachuestts, and return to her homeland, where she could leave Howard in the care of her parents, get a governess job, and possibly help with the reconstruction of France. 6 Crowley could practically read Leah’s mind and agreed that they would need a governess for their new child. Besides, Howard would be an ideal playmate for Hansi. Recognizing another kismet in the Great Work, he arranged to meet Mrs. Shumway in Paris and offer her a position.

A pallid, wilted woman of twenty-five, she stood five feet, two inches tall with gray eyes and brown hair, listlessly holding her child’s hand. Ninette Shumway reminded him of Ratan Devi. The boy was as white and lifeless as her, clinging tightly to his mother and crying incessantly. “They gave me the shock of my life,” Crowley recalled. 7 Offered a job, Ninette, in well-spoken but imperfect English, accepted. She returned with Crowley to Fontainebleau, where they and Leah stayed in a rented house at 11-bis rue de Neuville. Here, Crowley pondered potential locations for his Abbey of Thelema.

Ninette Shumway (1894–1990) and her son, Howard. (photo credit 14.1)

On January 30, Crowley called on his old mistress, Jane Chéron, hoping to make love, smoke opium, and catch up with Walter Duranty. He struck out on all three counts: Duranty was still on assignment in Russia for the New York Times , and Chéron was disinclined to both sex and drugs. However, when Crowley prepared to leave empty-handed, Jane insisted, “Shut your eyes!” Then she unfurled a piece of cloth and told him he could look.

His stunned eyes beheld a four-foot silk appliqué reproduction of the Stele of Revealing. She explained that in February 1917 she and her “young man”—almost certainly Duranty—searched the south of France for a cure for opium addiction. Suffering from insomnia, she awoke one day after dozing off to realize she had drawn, in her sleep, a reproduction of the Stele. This so impressed her that she spent the next three months reproducing it in silk. Such a labor from a woman uninterested in magick also impressed Crowley. That this encounter should come at such a crucial time in his life was, to Crowley, an unmistakable sign that he was on the right course with this Abbey business.

AC’s priapic tendencies did not end with Chéron. He continued writing passionate letters to the distant and faceless Jane Wolfe: “Now I see you before me shining in the dark—I turn out the lights for a little—I hold you closely—our light kindles—.” 8 Impatient for her to visit, he arranged a meeting in Bou-Sâada on June 25, the place and date of his Magister Templi initiation.

Eventually, however, his desires found a more practical object: Ninette Shumway. It began innocently enough, the two taking long walks in the country while Leah convalesced. Crowley soon dubbed her “Beauty,” and Shummy, as she was otherwise known, found him increasingly attractive. Then, one afternoon after lunch at the Barbison, Beauty and the Beast walked in the Fontainebleau forest. The vernal weather made them feel young, the wine made them giddy, and the danger made her irresistible. They chased each other through the glade and finally fell into each other’s arms with a passionate clasp. Crowley and Shummy soon began doing sex magick to locate a suitable Abbey.

Curiously enough, Leah did not object. She knew that, as the Scarlet Woman, she was number one in Crowley’s book. Furthermore, she understood the promiscuous interpretation of “Love under will” and found it was one Crowley encouraged without double standards. Ninette, however, brooded jealously and insecurely about sharing her man.

At 5 o’clock on the morning of Thursday, January 26, Leah’s water broke. She went to the hospital in Fontainebleau and, after an easy labor, gave birth to a daughter at 12:05 that afternoon. She looked like her mother except for the mouth, which was unmistakably Crowley’s. On March 8, Leah returned home from the hospital.

Ever the magician, AC named the baby Anne Lea—after the goddess of summer and the Scarlet Woman, respectively—thus giving her the monogram AL, the Hebrew name of God and the key to The Book of the Law . However, when little Howard declared during a walk in the forest, “I shall call her Poupée,” the name (French for “doll”) was so spontaneous and appropriate that they unanimously adopted it as her nickname.

Shortly after Poupée’s birth, Ninette herself became pregnant.

Although the I Ching directed them to locate the Abbey in Cefalù, Italy, they lacked the money to do so. Thus, on March 21, Crowley took Leah and Poupée to London, where Leah stayed with AC’s aunt and arranged finances with his lawyer; evidently, Crowley had £700 coming in another inheritance. He then fetched Shummy and “the brats” from France and proceeded toward Cefalù. He thought it a good omen that his train seat was number 31, a key value in The Book of the Law . The money arrived for them in Naples on March 30, allowing them to continue to their destination.

Cefalù was a small seaport with only one main street, located northwest of Sicily and thirty-seven miles from Palermo. In ancient times, when known as Cephaloedium, it allied with Carthage in 396 BC and was taken by the Moors in 858 AD. More recently, it was known for its marble quarries and the cathedral built by the great Norman hero Count Roger. Here, one night in a dingy hotel changed their lives. When Crowley swore not to stay another day in such despicable lodgings, Giordana Giosus overheard and told them he had a villa for rent. Crowley, again seeing fate’s hand, agreed to view the place.

A sinuous path just beyond town wound up the mountainside to an eighteenth-century villa known as the Villa Santa Barbara. Located south of the rock of Cephaloedium and just beyond a Capuchin monastery, it faced the sea amid a field of grass, trees, and a garden. It was a single-story stone structure, encased in plaster and painted all white except for the red-tiled floor. Five rooms and a shelf-lined pantry flanked its large central room, which Crowley immediately saw as a temple. 9

Crowley assessed the place rapidly. Despite a complete lack of plumbing, gas, and electricity, it had everything he needed: a temple, access to water, and rocks to climb. The size was ample. And near the building, Crowley noted two Persian nut trees; just as they were a sign for the Villa Caldarazzo in 1911, so in Crowley’s mind were they good omens for Cefalù. He struck a deal on the spot to rent the Villa Santa Barbara as the Abbey of Thelema.

They moved in immediately and that evening blessed the grounds with an act of sex magick. “Salutation to the Gods and Goddesses of this place! May they grant us abundance of all good things, and inspire me to the creation of beauty,” 10 he wrote in his journal. And so the Inglesi, Sigñor Caroli, began to prepare the Abbey of Thelema. He dubbed the main building the “Whore’s Cell,” and turned the main room into a temple: he painted a circle on the floor and placed in its center an altar, a copy of the stele, The Book of the Law , numerous candles, and other implements. The Throne of the Beast sat in the east, facing the altar in the center of the room. The Scarlet Woman’s throne sat across from this, in the west. Statues of various gods were placed around the room. The temple, according to Crowley’s design, would be open to all students at the Abbey.

The children soon quit sniveling and became active, healthy boys, Hansi taking to swimming and Howie to chess. Crowley would approach the boys in the morning and point to the sky. “Up there is the sun. When it gets over there , you may come back.” Thus he sent them off to play, and they would invariably return with fruits stolen from local farms or Sicilian bread given to them by the farmers. Equally often, one or both lost their clothes. And they were always full of stories of the day’s adventures.

For Crowley, this was paradise.

The question “Why Cefalù?” naturally arises, and the answer lies in a confluence of several influences. One was the migration to Italy of the literati he admired. Much as he was an individualist, Crowley nevertheless emulated those he esteemed, and validated himself by comparison to them. Thus he modeled not only his poetic style but even the byline of Aceldama (1898) after Shelley; when he left Cambridge without a degree, he followed the footsteps of Byron, Shelley, Swinburne, and Tennyson; after introductions by Gerald Kelly, he became a fixture at Le Chat Blanc in Paris; and he followed Allan Bennett and Oscar Eckenstein to India. Years later, when commenting on being expelled from Italy, Crowley would remark tellingly, “Like Mr. H. G. Wells and many other distinguished Englishmen, my presence was not desired by Mussolini.” 11

Another impetus stemmed from his newfound love of art and the model presented by postimpressionist painter Paul Gauguin (1848–1903). Gauguin was a successful stockbroker whose pursuit of painting led him to abandon his career, wife, and children. In 1891, at age forty-three, he moved to Tahiti and married a native girl. He moved into a cottage that he called the “House of Carnal Pleasure” and filled it with his paintings. Similarly, Crowley, having himself squandered his fortune and divorced his wife, had, at age forty-four, moved to a remote villa he dubbed the “Whore’s Cell” to pursue art. The influence of Gauguin is unmistakable; Crowley paid the painter a high honor by adding his name to the list of saints in his Gnostic Mass in 1921. The versions published in The International (1918) and the blue Equinox (1919) do not contain his name, although subsequent editions do. Clearly, Crowley regarded Gauguin as a kindred spirit.

Crowley’s works are relatively silent on the topic of Paul Gauguin; so what prompted this interest in the painter nearly twenty years after his death? Crowley did not say, although one possibility exists in W. Somerset Maugham’s fictionalization of Gauguin’s life, The Moon and Sixpence (1919), which had just come out. It is easy to imagine Crowley identifying with protagonist Charles Strickland, a man whose single-minded devotion to art ruined his finances and family and even drove his wife to suicide. Strickland’s comment,

“I don’t want love.… I am a man, and sometimes I want a woman. When I’ve satisfied my passion I’m ready for other things. I can’t overcome my desire, but I hate it; it imprisons my spirit; I look forward to the time when I shall be free from all desire and can give myself without hindrance to my work.” 12

is echoed epigrammatically by Crowley: “The stupidity of having had to waste uncounted priceless hours in chasing what ought to have been brought to the back door every evening with the milk!” 13 Crowley and Strickland even shared a passion for chess. Maugham’s description of the artist’s mural-covered walls in Tahiti is especially evocative:

From floor to ceiling the walls were covered with a strange and elaborate composition. It was indescribably wonderful and mysterious. It took his breath away. It filled him with an emotion which he could not understand or analyse. He felt the awe and the delight which a man might feel who watched the beginning of a world. It was tremendous, sensual, passionate; and yet there was something horrible there, too, something which made him afraid. It was the work of a man who had delved into the hidden depths of nature and had discovered secrets which were beautiful and fearful too. It was the work of a man who knew things which it is unholy for men to know. There was something primeval there and terrible. It was not human. It brought to his mind vague recollections of black magic. It was beautiful and obscene. 14

As will be seen, this idea would greatly influence Crowley.

While there is no evidence that Crowley actually read The Moon and Sixpence , Maugham’s book fits chronologically. There’s also an appealing justice to think that the author who modeled Oliver Haddo after Crowley later influenced Crowley to model himself after another of his characters: art imitating life, and life imitating art.

On April 14, Leah and Poupée arrived at the Abbey to complete the family. She and Crowley signed the lease to the villa as Sir Alastor de Kerval and Contessa Léa Harcourt. In this spiritual haven, they donned new names: Crowley became Beast; Leah was Alostrael, Virgin Guardian of the Sangraal; Ninette was Cypris; Howie and Hansi became Hermes and Dionysus. And Poupée, who arrived ill from England, drank goat’s milk, which nourished Jupiter.

They quickly developed a schedule for work at the Abbey: every morning, Leah would rise, strike a gong, and proclaim the Law of Thelema. Everyone present, even the children, would respond with “Love is the law, love under will.” Everyone would follow with the solar salutations of “Liber Resh” (to be practiced morning, noon, sunset, and midnight). Sitting down to a breakfast prepared by Ninette, they would “Say Will,” which was Crowley’s answer to grace. He would begin meals by rapping on the table to call all to attention. “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law,” the diners would say. Crowley, in response, would ask, “What is thy will?”

“It is my will to eat and drink,” came the reply.

“To what end?”

“That my body may be fortified thereby,” came the reply.

“To what end?” he pressed on.

“That I may accomplish the Great Work.”

With that, Crowley would declare, “Love is the law, love under will.” This ritual—or some variation thereon—began the meal. They would then eat in contemplative silence. These progressive questions betrayed his father’s influence, recalling Edward “Get-Right-with-God” Crowley’s repeated use of the question “And then what?” to lead up to his own trademark statement.

Aside from these regimented tasks, the rules permitted individual work and study. Climbing, swimming, studying, and writing filled most days; Ninette, after finishing her housework, took long walks. And in keeping with his philosophy, Beast bought drugs from a Palermo pusher named Amatore and made them available to all residents of the Abbey; his goal was not to encourage drugs, but to make them so readily accessible that he removed all temptation.

With routine at the Abbey established, all that remained was to send invitations to his students.

Leah’s arrival on April 14 left Ninette intensely bitter and jealous. In her experience, Leah had always been a convalescing and nonthreatening other woman, and even though she knew better, Ninette felt on top of the situation. She enjoyed having Beast all to herself while Leah was in England, but now the master bedroom belonged to Leah. The Virgin Guardian of the Sangraal commanded Beast’s attention and affection, and Ninette felt rejected.

On April 20, less than a week after Leah’s arrival, their ménage à trois slipped into an emotional morass. That night, all three got intoxicated and aroused; Beast, following an intense sexual performance, jokingly remarked, “You girls would wear out any man’s tool, were it steel or stone. Would God that you were Lesbians and I could sleep alone!” Leah, taking the jibe goodheartedly, made mock overtures toward Ninette, who grabbed a thin cloak to cover her nakedness and dashed into the rain. Crowley cursed and pursued her, fearing what mischief she might discover in her recklessness. Meanwhile Leah fumed, seeing through Shummy’s attention-getting ploy and knocking back some more liquor. Eventually she persuaded Howard to call for his mother.

An hour of searching finally uncovered Beauty, whom Beast convinced to return home. Ushering her into the Whore’s Cell—past Leah, who cursed drunkenly at her—and into bed, Beast emerged to find Leah vomiting. He soothed her next. Finally, he produced his manuscript of the Tao Teh King and recited from it to return their minds to a higher plane. As he read, he smirked inwardly. “Next please! Let’s all live up to ‘Never dull where Crowley is.’ ” 15

The following day, Poupée’s health worsened visibly. Unable to absorb food, she was literally wasting away. This was precisely the augury which the I Ching had given for Poupée’s birth: Hexagram XLI, Diminution. Beast consulted her progressed astrological chart and found Saturn and the sun both opposing Mars: this was bad, and he feared she might not live through the week. “I have been howling like a mad creature nearly all day,” he recorded in his journal. “I want my epitaph to be, ‘Half a woman made with half a god.’ ” 16

To take his mind off his troubles, Beast immersed himself in writing and painting. If he was lucky, he slept at odd times, but in the main he suffered chronic insomnia. And, even though Poupée survived the next week without incident, Crowley’s symptoms continued. This was because the insomnia was not due to stress but to his continuing abuse of heroin and cocaine.

Crowley soon found himself with two expectant “wives” when Leah became pregnant again that May.

On June 21, Leah was with Beast on a train to meet Jane Wolfe. However, he left her in Palermo and continued alone to his rendezvous in Tunis. Beast had become obsessed with the mystery of Jane Wolfe. Having reconsidered summoning Jane to a summer clime as inhospitable as Bou-Sâada’s, he had wired her to meet him in Tunis instead. “I adore her name,” he anticipated her arrival. “I hope she is hungry and cruel as a wolf.” In his diary, he wrote,

I am hers.… I die that She may live.… I drown in delight at the thought that I who have been Master of the Universe should lie beneath Her feet, Her slave, Her victim, eager to be abased. 17

His health failed in Tunis, and he recorded in his diary, “A most unpleasant day of severe illness. I think I may have been poisoned by reading Conan Doyle.” 18 More likely, his illness stemmed from the same sanitary conditions at Cefalù that had given Leah dysentery a month earlier.

When the appointed day came and went without Jane Wolfe’s arrival, Crowley filled himself with cocaine and wrote “Leah Sublime,” a poem dedicated to his Scarlet Woman. While not as subtle or artistic as the poems he wrote for Rose, it certainly holds a unique place in Crowley’s corpus, collecting all his filth into one poem. Its most memorable (and polite) lines were:

By July 3, Crowley impatiently scribbled in his diary, “I shall certainly not wait for more than two weeks for her, one only has to wait three for Syphilis herself.” After a few more fruitless days, he gave up. Crowley returned to Cefalù on July 10.

At this time, Crowley was undergoing what Norman Mudd would later describe as the “mystery of filth,” and Leah happily indulged his wishes. Thus, on July 22, Crowley experimented with masochism in a bedroom game wherein Leah became a dominant, menacing tyrant, exclaiming at Crowley:

So low art thou—crawl to my floor-blackened feet, and call them snow-pure marble.… You dog! to your slaves’ task! to your mock Love, you dog! You dirty dog! Do it, you dirty dog! To my soiled feet, lap them … 20

While the actions of consenting adults are a private matter, this incident is of biographical interest because it sheds light on his perspective. As Gerald Yorke stated about AC’s sexuality: “Crowley didn’t enjoy his perversions! He performed them to overcome his horror of them.” 21 Thus he followed the path of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis to deprogram his mind of Victorian mores. 22

Sitting in her Bou-Sâada hotel room, Jane Wolfe cursed Crowley’s name. Having left home a month ago, she had still to reach her destination. Complicating matters was a cryptic cable from Palermo:

COMME CEFALU

Nobody could shed light on the missive. She had always said Los Angeles was the modern Athens, and it seemed preferable to the Mediterranean. An actor with the Pathé Motion Picture Company, a French company filming on location in Bou-Sâada, finally provided the translation. “It is in English,” he remarked to her surprise. “It says ‘Come Cefalù.’ ” Thus Jane made her way via Algiers, Tunis, and Sicily to the Hotel des Palmes in Palermo. Directed to a second-floor waiting room, she relaxed with a heavy sigh, closing her eyes and resting her head in her palm. Forty days of delays and itinerary changes since leaving Los Angeles left her exhausted.

Actress Jane Wolfe (1875–1958). (photo credit 14.2)

A man’s high, thin voice pierced the silence. “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” She opened her eyes to find AC and Leah in the room with her. In that instant, all their romantic illusions shattered.

Jane’s first thought was “filth personified.” Leah was unwashed and ungroomed, with charcoal-blackened fingers. Crowley, with a striped suit, walking stick, and hat, presented a more wholesome picture, but her clairvoyant sight presented her with a terrifying vision of a bird trapped in mud. Likewise, the actress made a disappointing first impression on Crowley. After months of anticipating the arrival of his “movie star,” he discovered she was older than he anticipated; she was also more masculine, haggard, and unattractive than he had hoped. As he wrote in his diary, “I am like the girl who was to meet a ‘dark distinguished gentleman’ and did, he was a nigger with one eye.” 23

Proceeding to the Abbey the next morning, Jane encountered more rude surprises. It was as filthy as its inhabitants. Finding Ninette five months along in her pregnancy with only one man in the Abbey, Jane deduced Crowley was the father. Having come to Cefalù expecting to be Crowley’s lover, she found the job filled twice over … not that she wanted to be his lover, on closer inspection.

As a newcomer to the Abbey, Jane had three days to adjust to the schedule. She stayed for a time in the Whore’s Cell, but ultimately ended up in the Abbey’s second building. Called the Umbilicus, it was the nursery where Ninette stayed, babysitting and cooking. After three days, Crowley put Jane on a rigorous schedule of yogic exercises and had her typing his manuscripts. Despite his constantly belittling her previous visions—particularly her Persian Master named Schmidt—Jane finally understood that Beast was merely breaking down her preconceptions. After a week or so, she relaxed enough for a new task: to help paint the Chamber of Nightmares.

La Chambre des Cauchemars

was Crowley’s name for the main ritual room after decorating it with three grotesque and disturbing murals. Its north wall, dubbed La Nature Malade

, depicted hell as “false intellectual and moral consciousness”; it bore scenes such as “Japanese Devil-Boy Insulting Visitors,” “Faithful on the Gallows” and “The Long-Legged Lesbians.” The wall depicting heaven, subtitled “The Equinox of the Gods,” encapsulated the A A

A teachings and Holy Books with the theme “Aiwass gave Will as a Law to Mankind through the mind of The Beast 666.” The mural of earth, finally, depicted love in terms of the base desires it spawned. “The purpose of these pictures is to enable people, by contemplation, to purify their minds,”

24

Crowley wrote. Once unaffected by this lurid sensuality, Crowley believed, the mind was clear of the life-negative taboos and mores of Judeo-Christian culture.

teachings and Holy Books with the theme “Aiwass gave Will as a Law to Mankind through the mind of The Beast 666.” The mural of earth, finally, depicted love in terms of the base desires it spawned. “The purpose of these pictures is to enable people, by contemplation, to purify their minds,”

24

Crowley wrote. Once unaffected by this lurid sensuality, Crowley believed, the mind was clear of the life-negative taboos and mores of Judeo-Christian culture.

“There, in the corner, are Lesbians as large as life,” Crowley would tell visitors. “Why do you feel shocked and turn away: or perhaps overtly turn to look again? Because, though you may have thought of such things, you have been afraid to face them. Drag all such thoughts into the light … ’tis only your mind that feels any wrong.… Freud endeavors to break down such complexes in order to put the subconscious mind into a bourgeois respectability. That is wrong—the complexes should be broken down to give the sub-conscious will a chance to express itself freely.…” 25

Poupée became so sick that Leah took her to the doctor in Palermo on October 8. Although the parents desperately attempted sex magick to cure her, Beast was so grief-stricken that he broke off the operation. On October 11, Poupée went into the hospital. The following day, Crowley passed what he considered his saddest birthday. Waiting and worrying, he returned to Cefalù and tried to lose himself in poetry and painting. It was useless.

On October 14, Leah came home alone. Her heavy sobs said everything. Shattered by grief, Crowley led her into the main temple and pronounced a blessing on Poupée’s soul. In her diary, Leah recorded the tragedy:

A Thelemite doesn’t need to die with a doctor poking at him. He finishes up what he has to do and then dies. That’s what Poupée did. She didn’t pay attention to anything or anybody. Her eyes grew filmy and she died with a grin on her face. Such a wise grin. 26

Leah was inconsolable, her grief impenetrable. She would not heed Beast’s advice to rest and began suffering nocturnal pains, followed on October 18 by heavy spotting. Although Beast sent Ninette after a midwife, it was too late. Besides losing her daughter, Leah had miscarried. She was so far along in her pregnancy that they had to call in a surgeon. “I stood as if petrified in the studio while in the next room the surgeon drew forth the dead from the living,” Crowley wrote. Learning that the unborn child would have been a boy, he added, “My brain was benumbed. It was dead except in one part where slowly revolved a senseless wheel of pain.” 27 In the end it was Leah, suffering physical and psychological loss, who mustered her remarkable inner strength to urge Beast to persevere in the Great Work despite the tragedy.

When Leah noticed that Ninette, who’d always envied her place beside Beast, experienced an uncomplicated pregnancy, she convinced herself that Ninette had caused her misfortune. On November 3, after another of Leah’s tirades, Beast humored her and skimmed through Ninette’s diary. (At the Abbey, all residents made their magical records available to Beast for perusal and comment.) What he read made him feel physically ill. Her diary’s hostility and jealousy convinced him that Ninette’s negativity had indeed claimed the lives of both infants. He entered the temple and exorcized the shadow. Banishment was the only solution, so he left a note for Beauty:

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.

Initiation purges. There is excreted a stench and a pestilence. In your case two have been killed outright, and the rest made ill. There are signs that the process may lead to purification and things made safe within a short time. But we cannot risk further damage; if the hate is still in course, it had better coil back on its source. Keep your diary going carefully. Go and live in Cefalù alone; go to the hospital alone; the day before you come out send up your diary, and I will reconsider things. I shall hope to see the ulcers healing. Do not answer this; simply do as I say.

Love is the law, love under will.

666 28

On November 5, Ninette left the Abbey and went into Palermo to have her baby. She gave birth on Friday, November 26, to a daughter, whom Crowley named Astarte Lulu Panthea; he readmitted Shummy to the Abbey.

C. F. Russell arrived at the Abbey on November 21, full of stories of his exploits of the last two years: how, as a Pharmacist Mate First Class aboard the USS Reina Mercedes in Annapolis, he injected forty grains of cocaine on November 24, 1918, as a magical experiment, resulting in his December 12 discharge; 29 how he made his way to Detroit in May 1919 and helped with the Great Work there; and how he applied for a passport on October 11, 1920—with Ryerson vouching for him—so he could come to Italy for study. 30 His sailor’s coarseness estranged him from the residents, prompting Beast to describe him as “a husk of 100% American vulgarity which conceals a Great Adept.” 31 Jane Wolfe was not so kind:

From the way Russell has done the odd jobs around here, I am bound to say he either lacks intelligence, lives in another world entirely … or does not care especially how a thing is done. 32

Crowley nevertheless saw his potential. Shortly after arriving at the Abbey, he became a Probationer in the A A

A as Frater Genesthai, and Beast prepared to conduct, with him and Leah, the first major magical operation since 1918’s Amalantrah Working.

as Frater Genesthai, and Beast prepared to conduct, with him and Leah, the first major magical operation since 1918’s Amalantrah Working.

The Cephaloedium Working had three goals: to inspire Crowley to finish writing a commentary on The Book of the Law; to invoke Hermes and Apollo; and to obtain true understanding of the tarot trump “The Tower.” The participants included Leah, who ceremonially wore a scarlet Abbai girt with a sword; Russell, who wore a black robe with a gold lining; and Crowley, who wore orange and bore a Janus-headed wand entwined with four serpents. They began with a banquet of fish and yellow wine, then, after appropriate banishings, purifications and consecrations, took an oath:

Hear all that we, To Mega Therion

9°=2D

A A

A The Beast; Alostrael, The Scarlet Woman; and Genesthai

0°=0° A

The Beast; Alostrael, The Scarlet Woman; and Genesthai

0°=0° A A

A do now in The Presence of TAHUTI most solemnly swear to devote ourselves to the Establishment of The Book of the Law

as authored by Aiwaz 93 to 666 by the Way of the Cephaloedium Working as in the record thereof it hath been written.

do now in The Presence of TAHUTI most solemnly swear to devote ourselves to the Establishment of The Book of the Law

as authored by Aiwaz 93 to 666 by the Way of the Cephaloedium Working as in the record thereof it hath been written.

After invoking the gods by song and dance in the tradition of the Paris Working, AC and Leah disrobed and got Russell high on ether. Their intent was to coax him to make love to Crowley, who would thereafter make love to Leah; scryings and prophecies would follow thereafter. Unfortunately, the plan failed. As Russell recalled,

Your Circean enchantment didn’t give me a bone-on—add that Ethyl Ether is no aphrodisiac—you were in bed between me and the Virgin (sic) Guardian of the Sangraal who had to lean over you to do what she did and you played down in the Record—in fact more than merely to shake the hand of a stranger faire gonfler son andouille . 33

The working ultimately ended on a sour note, Beast deeming it a failure on January 20, 1921.

With the unhappy end of the Cephaloedium Working, Beast and Leah traveled to Palermo. With a vow to “give the body to whoever should desire it,” 34 the lovers parted, AC heading to Paris to recruit new students while Leah stayed in town with their landlord, Baron Carlo la Calce. Monsieur Bourcier again let Crowley stay on credit in his Hôtel de Blois at 50 rue Vavin. Nina Hamnett, who saw Crowley regularly at this time, found him despondent and miserable, shattered by Poupée’s death. After passing the hospital where Poupée had been born, he retreated to the forest of Fontainebleau, a place that had always been special to him, and broke down sobbing.

Hamnett introduced Crowley to budding writer and poet Mary Francis Butts (1890–1937), who contributed to The Little Review and The Transatlantic Review . One might call her literary and artistic interests hereditary: her grandfather, Thomas Butts, had been a patron of poet, artist, and Gnostic Catholic Saint William Blake (1757–1827). 35 Her father, likewise, befriended several pre-Raphaelite artists. Butts and Crowley shared a lot in common: Mary was very close to her father, who died in 1904 when she was thirteen. Like Crowley, she lived on a small annuity from her inheritance but tended to over-spend. Also like Crowley, she attended college (from 1909 to 1912) without completing a degree. After a string of lesbian relationships during the war years, Butts married Jewish writer and publisher John Rodker (1894–1955) in 1918, and had a child in November 1920. She had a serious and long-standing interest in the occult and had even spent time the previous year studying Éliphas Lévi’s works at the British Museum. Fair and winnowy, her beaming blue eyes, fiery red hair, and boundless energy nevertheless made her seem immense. Of her, Crowley later wrote, “My relations with her were never very intimate. We enjoyed exchanging views.” 36

When she met Crowley in 1921 she was in the process of separating from her husband and forging an emotional and spiritual bond with writer James Alexander Cecil Maitland (d. 1926). Maitland was “a lovable but dilapidated Scotch ‘aristocrat’ ” 37 whose grandfather worked on the Revised Version of the Bible, and whose father was a Catholic clergyman. Interested in magic and the occult from an early age, he was known to draw chalk circles on the floor of his Belsize Park apartment and attempt various conjurations. Butts and Maitland had, the previous year, ritually bonded by cutting crosses on each other’s wrists, sucking and kissing the other’s wound.

Crowley instructed them both in basic techniques of magic, meditation, and yoga, and conducted several experiments with them in astral projection. Butts excelled at the latter, referring to herself as a “secular Isis.” Butts’s journals from this period include long entries detailing her magical practices, astral visions, and spiritual meditations. On March 11 she took her I° initiation into OTO, 38 and on the 18th Crowley taught her the “gnostic cross.” 39 She approached Crowley with caution, noting “Aleister is an assistance, not a good or an evil. It is a good practice to notice a phenomena and its antithesis.… In that case it depended which way you looked.” 40 However, she would later write of Crowley, “I believe the Beast to be a technical expert of the highest order.” 41 Her impressions of Thelema were likewise favorable, noting in her diary, “I believe in ‘Do what thou wilt’ etc.” 42

When Crowley invited the couple to stay at the Abbey, they hesitated at first. As Butts noted in her journal, “Aleister Crowley must know by now that we are playing for time with regard to Cefalù, i.e., that we won’t come to him unless driven there by poverty or are reassured as to his intentions.” 43 Whatever their reservations, they were evidently assuaged, as Butts and Maitland would arrive that summer for a stay at the Abbey.

Hamnett also introduced Crowley to John Wilson Navin Sullivan (1886–1937), former mathematical and scientific reviewer for the London Times and Athenaeum . His friend Aldous Huxley described him as having “a very clear, hard, acute intelligence, and a very considerable knowledge, not merely on his own subjects—mathematics, physics and astronomy—but on literature and music. A stimulating companion.” 44 Educated at University College, London, he had broad interests in science, mathematics, literature, and music, and contributed articles to newspapers and periodicals. He even wrote a novel, An Attempt at Life . 45 In the years to follow, Sullivan would establish himself as one of the foremost popularizers of science, combining his love of mathematics, physics, philosophy, and music into classic books like Aspects of Science, Beethoven: His Spiritual Development , and The Limitations of Science . 46 He was one of the few people in Britain to understand the theory of relativity when it was first introduced, and when Einstein visited the University of London, Sullivan was the only journalist able to discuss it in Einstein’s native German. 47 His interest in the intersection of science and aesthetics made him a natural foil for Crowley’s thinking; the following quote from Aspects of Science easily could have flowed from AC’s own pen:

Mathematics, as much as music or any other art, is one of the means by which we rise to a complete self-consciousness. The significance of mathematics resides precisely in the fact that it is an art; by informing us of the nature of our own minds it informs us of much that depends on our minds. 48

They spent long nights playing chess and discussing mathematics. Sullivan had no interest in the occult 49 but, when he responded to Beast’s discussions of The Book of the Law by seeing numerical theorems in its passages, Crowley excitedly invited him to the Abbey to write a mathematical proof of Liber AL .

Sullivan’s wife, (Violet) Sylvia Mannooch (b. 1896), 50 was a beautiful, tragic figure trapped in an unhappy marriage. They shared only a love of music, and Sullivan’s preoccupation with mathematics much eroded even this. Both realized their relationship was pointless. When Sullivan vowed to AC to find his true will, Sylvia became a greater hindrance. Crowley recalled, “He asked me point-blank to take her off his hands for a time.” 51 Crowley agreed and told him, “You can have her back whenever you like by whistling for her.” It was a replay of his affair with Ratan Devi at the behest of her husband.

As in the original liaison, Sylvia became pregnant. She and Beast planned to return to Cefalù, where Sullivan would meet them and write his precis on Liber AL . Sullivan, however, met them at the dock during lunch and demanded, “I want Sylvia back.”

“Righto!” Crowley nodded his head, stuffing food in his mouth and swallowing. “I’ll have to get the cabin changed and take a few of Sylvia’s things out of my trunk.” 52 The scene was a perfect picture of irony, with Crowley agreeable, Sylvia enraged, and Sullivan flabbergasted. In the end, Crowley returned to Cefalù alone. Sylvia would die of typhoid shortly thereafter. 53

Over the years, the relationship between Fratres Merlin Peregrinus and Baphomet had grown strained: Crowley had lost respect for the head of OTO, finding Reuss’s experience in the IX° to be unsatisfactory and nearly nonexistent. As AC wrote of Reuss, “He told me that he had applied it with success but twice in his whole life.” 54 Likewise, Reuss’s own doubts about Crowley resulted in bitter correspondence wherein he denounced The Book of the Law; however, when he visited Beast in Palermo, it was on civil terms. No record survives of this summit. However, when Reuss suffered a stroke shortly thereafter, Crowley claimed to have been named his successor as Outer Head of the Order, pending election by all the world heads. Four years would pass before the appointment was ratified.

Beast returned to the Abbey on April 6, where the following two months passed in miserable dullness. Although he concluded this signified the end of a magical cycle—and the I Ching confirmed this—he was unsure what to do next. Everyone, it seemed, was poor, depressed, and ill. Around May 20, as the sun entered the sign of Gemini, he and Leah conducted an operation of sex magick designed to release within her the power of Babalon. Although, in Leah’s mind, the ritual transformed her from simply being a Scarlet Woman, consort to the Beast, into Babalon herself, for Crowley the lull continued.

Then, on May 23, another inspiration seized Crowley. Sitting at his desk, he knew it was time to take the most awful obligation possible. He scribbled in his diary, “I am mortally afraid to do so. I fear I might be called upon to do some insane act to prove my power to act without attachment.” Then, at 9:34 p.m., his mind became calm. “As God goes, I go,” he told himself. Discarding his clothes, he entered the temple with Leah at his side. There, before his Scarlet Woman and all the powers of the universe as his witness, Crowley took the Oath of an Ipsissimus, (10°=1°), the final grade in the A A

A hierarchy. The oath began his final and greatest initiation, one that would not see its conclusion until 1924. In his diary, he wrote:

hierarchy. The oath began his final and greatest initiation, one that would not see its conclusion until 1924. In his diary, he wrote:

I am by insight and initiation an Ipsissimus; I’ll face the phantom of myself, and tell it so to its teeth. I will invoke Insanity itself, but having thought the Truth, I will not flinch from fixing it in word and deed, whatever come of it.

Along with the grade came the obligation never to advertise its attainment. This vow Crowley kept his entire life, the only hint of his attainment appearing in Magick in Theory and Practice (1929), where, among a catalog of his attainments up to the grade of Magus, he wrote that his holy guardian angel “wrought also in me a Work of Wonder beyond this, but in this matter I am sworn to hold my peace.” 55

By 10:05 p.m., Crowley was back at his desk.

Having had enough of Jane’s obstinate preconceptions and asinine visions, Beast decided she needed a magical retirement. It would span a month and involve six daily meditations: in the first week, these would each last thirty minutes; in the second week, the meditations would be an hour long; by the fourth week, she would be meditating twelve hours a day. Wolfe reacted poorly, however, when Crowley instructed her to go to the top of the rock of Cephaloedium for a month. “You’re crazy,” she told him.

“A boat leaves for Palermo in the morning,” he replied calmly but firmly, pointing to the open door of the Whore’s Cell. “There’s the door.”

When she grudgingly agreed to the retirement and Crowley told her she could take nothing with her—no books, games, visitors or other distractions—she objected again. “What am I supposed to do?”

Beast smiled sagaciously. “You will have the sun, moon, stars, sky, sea, and universe to read and play with.”

Unconvinced, she nevertheless began her retirement on June 13 on a secluded part of the beach designated by Crowley. Russell transported and pitched AC’s Himalayan tent, which she regarded disparagingly because the wardrobe trunk she brought to Cefalù was nearly the same size. Beginning the retirement, she vowed not to speak, except to reply “Love is the law, love under will” when Russell brought her meals—typically grapes, a loaf of bread, and a jug of water. Emotions washed over her that first day: she was nervous lest nothing happen. She missed the niceties of her Hollywood life and resented the rocks beneath her that made her bed and floor uncomfortable. Although angry at Crowley, she nevertheless determined to succeed.

Jane awoke the next morning feeling as if the ground beneath her was rocking and swaying. Looking out the door, she found the tent surrounded by the water of the high tide. Fortunately, Crowley and Russell had appeared to check on her and moved the tent back to dry ground. After that, her retirement proceeded as scheduled. Although she grew calm, boredom persisted. To amuse herself between meditations, she exercised and swam naked in the water. Finally, after nineteen days of solitude, her thoughts dissolved into “perfect calm, deep joy, renewal of strength of courage.” 56 Looking about, she understood what Crowley meant about the world being her toy. She had found both herself and a fulfilling spirituality.

At the end of the retirement, Jane returned to the Abbey looking better than ever. Not only had her disposition changed, but the exercise and diet trimmed off sixteen pounds.

Mary Butts and Cecil Maitland arrived at the Abbey on July 5, 1921, and were enchanted by the summer weather and setting. Butts arrived having recently outlined her objectives in studying magick:

I. I want to study and enjoy, and to enter if I can into the fairy world, the mythological world, and the world of the good ghost story.

II. I want by various mystical practices and studies to produce my true nature, and enlarge my perceptions.

III. I don’t only want to find my true will. I want to do it. So I want to learn how to form a magical link between myself and the phenomena I am interested in. I want power.

IV. I want to find out what is the essence of religion, study the various ideas of God under their images.

V. I want to make this world into material for the art of writing.

VI. I want to observe the pairs of opposites, remembering that which is below is as that which is above. From this I wish to formulate clearly, the hitherto incommunicable idea of a third perception. This is a perception of the nature of the universe as yet unknown to man, except by intuitions which cannot be retained, and by symbols whose meaning cannot be retained also. I want to fix it in man’s mind.

VII. I want to write a book not about an early theocracy and fall of man, … but a book written about the subject, historically, under terms of human fallibility without deification of Pythagoras or the writers of the Kabala.… A book to show the relation of art to magic, and shew the artist as the true, because the oblique adept. 57

In Thelemic parlance, it was her Will to be a writer, and she looked to magick to give her both discipline and subject matter for writing. Thus, while staying at the Abbey, she worked on editing her novel Ashe of Rings (1925). 58 However, writing was but one of her activities. There were, of course, the Abbey’s mandated activities and lectures. But she also continued her experiments with astral projection and studied Crowley’s unpublished works. These included Liber Aleph , his commentary on The Book of the Law , and the third part of Book Four which would later become Magick in Theory and Practice . As she read Magick , Butts made a number of recommendations on the content and additional topics for the Master Therion to cover. In his Confessions , Crowley acknowledged his debt to her:

I practically re-wrote the third part of Book Four . I showed the manuscripts to Soror Rhodon (Mary Butts) and asked her to criticize it thoroughly. I am extremely grateful to her for her help, especially in indicating a large number of subjects which I had not discussed. At her suggestion, I wrote essay upon essay to cover every phase of the subject. The result has been the expansion of the manuscript into a vast volume, a complete treatise upon the theory and practice of Magick, without any omissions. 59

Judging from her Cefalù diaries, Butts struggled with many aspects of life at the Abbey, her record punctuated by flashes of anger, disappointment, and doubt. She complained about the rationing of cigarettes, infrequent structured teaching, uninhibited sexuality (even in the presence of children), and the fact that “both [Hirsig and Crowley] dope out of all reasonable proportion.” Privately, she also speculated that Poupée had died because Leah had neglected her. 60 Even while helping with Magick in Theory and Practice , she records a remark by Cecil Maitland regarding the high esteem in which the Thelemites regarded Crowley: “it makes AC tragic, because he is a kind, wise, honourable, gentle man crucified by his utter belief in his own teaching.” 61 Nevertheless, she continued her magical work throughout, and offered suggestions on how to make the Abbey more inviting to other visitors. 62

Reading Herodotus’ account of an Egyptian priestess copulating with a goat in the course of a religious ceremony, Crowley pondered the occult significance of these “prodigies.” The unions of humans and animals was certainly sacred to ancient cultures: the Egyptians venerated gods who had human bodies and animals’ heads. Similar ideas appeared in Greek mythology, with the bull-headed Minotaur and the story of Leda and the swan. Other ancient religions around the world told similar tales. Thus Crowley suggested such a working. Leah agreed to act as priestess. They got a goat, and the Scarlet Woman knelt naked on the ground, presenting herself to the indifferent beast. Crowley tried coaxing the goat to mount Leah, but the animal failed to respond to a human female. To save the ritual from utter failure, Crowley took the goat’s place with Leah, as he recorded in his diary: “I atoned for the young He-goat at considerable length.” 63

On September 14, as their visit drew to a close, both Butts and Maitland signed A A

A Probationers’ oaths. Oddly enough, they left for Paris two days later. Back in London, Butts continued her magical work and struggled with her ambivalence, writing, “ ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.’ That is all right. But people are to be made aware of this by fear, coercion, bribery, etc., a religious movement re-enacted. The founder is to be Crowley and his gulled, doped women.”

64

In the end, she concluded the Abbey was a sham. “I’d sooner be the writer I am capable of becoming than an illuminated adept, magician, magus, master of this temple or another.”

65

Probationers’ oaths. Oddly enough, they left for Paris two days later. Back in London, Butts continued her magical work and struggled with her ambivalence, writing, “ ‘Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.’ That is all right. But people are to be made aware of this by fear, coercion, bribery, etc., a religious movement re-enacted. The founder is to be Crowley and his gulled, doped women.”

64

In the end, she concluded the Abbey was a sham. “I’d sooner be the writer I am capable of becoming than an illuminated adept, magician, magus, master of this temple or another.”

65

When Jane returned to the Abbey from her retirement, all were abuzz anticipating the arrival of Frank Bennett, VII°, Beast’s man from Australia. He was a senior member in Crowley’s circle, both in terms of his fifty-five years of age and his eleven years in the A A

A , and his visit posed a logistic puzzle: there was no room for him in the Whore’s Cell, and the Umbilicus, as a nursery, was

inappropriate for such an August Brother. Crowley asked Russell to give up his room for Bennett. The student refused, complaining that he needed to study and meditate. Jane, seeing Crowley bristle, quickly offered her room. At this point, however, the matter of a room was no longer the point. So the student sulked and the master stewed, until Beast grabbed a towel and told Russell sharply, “Your work doesn’t matter a tinker’s cuss. You’d better be out by the time I finish my bath.” However, he returned from the beach to find Russell still entrenched in the room. AC ultimately confronted him with the tack that had been so successful with Jane: he said he worried that Russell was working too hard and suggested he take a holiday from the Abbey for his own health.

, and his visit posed a logistic puzzle: there was no room for him in the Whore’s Cell, and the Umbilicus, as a nursery, was

inappropriate for such an August Brother. Crowley asked Russell to give up his room for Bennett. The student refused, complaining that he needed to study and meditate. Jane, seeing Crowley bristle, quickly offered her room. At this point, however, the matter of a room was no longer the point. So the student sulked and the master stewed, until Beast grabbed a towel and told Russell sharply, “Your work doesn’t matter a tinker’s cuss. You’d better be out by the time I finish my bath.” However, he returned from the beach to find Russell still entrenched in the room. AC ultimately confronted him with the tack that had been so successful with Jane: he said he worried that Russell was working too hard and suggested he take a holiday from the Abbey for his own health.

The student feared this meant banishment, so on July 18, the day after Bennett arrived, he climbed the rock of Cephaloedium and began a magical retirement. Cleaning his makeshift hut, he kept his mind active by counting the 273 handfuls of dirt and 219 small stones that he threw out. Then he brought in a stone slab to serve as an altar for the Thelemic Holy Books, a copy of the Stele of Revealing, his magical knife, and the Greek Zodiacal cross that Frater Achad had made for him. Then, at 8 p.m., he did the Lesser Banishing Ritual and resolved not to descend the rock for food or water for eight days. Less than an hour later, he began acting like a Master of the Temple, interpreting every event as a particular dealing of God with his soul. Waking early the next morning, he proceeded with solar adorations and recitations of the Holy Books.

Ninette, who considered Russell a child requiring gentle treatment, begged Beast to intervene. He simply shrugged his shoulders, “Let him come down. He’s up there by no will of mine .” Crowley thought Russell had lost his mind. “He has no sense of proportion, and so mixes the planes that he attaches real importance to the number of handfuls of dirt he finds in his hovel.” 66 Ninette, however, carried a rucksack of food and water up the rock. While Russell would neither talk nor eat, he was grateful for the water. On July 24, after a week on the rock, Russell descended shortly after noon and slept on the nursery’s living room floor. 67

As Crowley told the end of the story, the sound of his name being shouted hoarsely awakened Beast from his lunchtime nap. He opened his eyes just in time to see Russell, unshaven and bedraggled, drop a rucksack at his feet and run off whooping. He had supposedly visited the barber for a shave but, after being lathered, remembered his oath not to descend the rock for water and dashed out of the shop, shaving cream flying in all directions. When Crowley opened Russell’s rucksack, he found it full of incoherent diaries and concluded Russell had lost his mind.

Frank Bennett’s spiritual awakening occurred during a walk on the beach with Leah and Beast. The morning was cloudless and still, the sea a clear indigo. Although a poor swimmer, Bennett joined the other two in the water and afterward sat naked with them in the shade, admiring the scenery. “Progradior,” Beast launched into a lecture, “I want to explain to you fully, and in a few words, what initiation means, what is meant when we talk of the Real Self, and what the Real Self is.” In speaking, he equated the holy guardian angel with the subconscious mind: illumination began when one let it work without interference from the conscious mind, for the conscious mind repressed impulses of the subconscious, resulting in restriction and evil. “There is no sin but Restriction,” The Book of the Law said, and it applied here. The most ubiquitous urge, which was constantly repressed to the detriment to our mental and physical health—and Freud concurred with this—was sex. Rather than treat it as an unfortunate and shameful accident of nature, AC saw it as a basic part of himself, not only physically but as a symbol of God’s ability to create.

This was news to Bennett, who thought the holy guardian angel was super-conscious. If Crowley was right, then all he had to do was listen to his subconscious. That was one meaning of “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” The revelation made his head reel. He next had a wild impulse. Rather than ignore it, he gave in. Bennett ran down the beach and jumped into the water, joined shortly thereafter by Leah and Crowley. After the swim, Bennett excitedly asked Beast, “Please tell me again what you said just now.”

“How the devil should I remember?” he asked, but with Bennett’s reminders, he reconstructed the discussion as best he could. Bennett smiled with satisfaction. “You have given me the key to the inmost treasury of my soul.”

Returning to the Abbey, he pondered his illumination, musing, “I wish I knew this before. It would have saved me a lot of misery.” Going to bed at eleven that night, the churning in his mind kept him awake, and his head throbbed painfully with a pressure within, threatening to split. Suffering for four hours, suffocating, he rose from his sweat-soaked bed, threw open his window, and pressed his hands to his head to ease the pain. Then, palms to temples, Bennett dashed out into the night, gasping for air like a drowning man. Finally, a voice deep within instructed, “Breathe deep.” When he did, his body relaxed. He felt the sweat coating his skin, the stones and thorns pressing into his feet. The pain dissolved, and the pressure folded upon itself. Bennett returned to the Abbey thirty minutes after leaving and quickly fell asleep. “Absolute blackness pervaded my whole being,” he recorded in his journal.

Bennett stayed in his room the next day and went to bed early. His claustrophobia returned that evening, but one thought penetrated the chaos in his brain. Bennett grabbed a piece of paper and desperately scribbled it down.

What fools we men are! We make for ourselves a prison, and erect mirrors that cover all the four walls of this prison; and not being satisfied with this, we cover the ceiling with a mirror as well. And these are our five senses which reflect themselves in hundreds of forms until we are so befogged that we believe that these reflections of ourselves—of man as Man and Bull—are all that is. But there are a few who have examined these mirrors and polished them, and discovered that the more the mirrors are polished the less reflection they give. Then a time has come when they have found that they are not mirrors at all, but only veils, and that one can see through the veils. 68

Thus he understood that one could find one’s holy guardian angel.

On the third night of his trance, Bennett’s mind remained placid. He felt no pain or discomfort, and he understood Thelema better. In his diary he recorded what, in his mind, was conclusive proof of the Law’s importance: “Our Father, which art in Heaven, Hallowed be Thy Name. Thy Kingdom Come, Thy WILL be done …” Frank Bennett understood.

Frater Progradior, Frank Bennett (1868–1930). (photo credit 14.3)

As 1921 drew to a close, the Abbey’s visitors returned to their homes. Butts and Maitland’s appearance reputedly shocked their Parisian friends, with Nina Hamnett describing them looking “like two ghosts and were hardly recognizable.” 69 Goldring’s description of them in 1925, from South Lodge , shows no sign of the health-wrecked drug fiends he claimed the Abbey made of them; Butts would live on for another fifteen years, while Maitland would commit suicide in 1926, the year after he and Butts parted company.

Frank Bennett, meanwhile, advanced to the A A

A grade of Adeptus Major (6°=5°) and the OTO grade of IX° during his stay. Beast gave him a X° charter as head of the Australian OTO on October 5, and, in November, Bennett returned to Australia to set up branches of OTO and A

grade of Adeptus Major (6°=5°) and the OTO grade of IX° during his stay. Beast gave him a X° charter as head of the Australian OTO on October 5, and, in November, Bennett returned to Australia to set up branches of OTO and A A

A .

.

The year 1922 began with a visit from Ninette’s two sisters. Her twin, Mimi, thought Crowley impressive, while Helen Fraux found him loathsome. When Beast threw out the latter sister for trying to poison the children’s minds,

she went to the Palermo police with all sorts of wild stories. A resulting visit and search of the Abbey by the sotto-prefetto

turned up nothing to validate her complaints. Shortly thereafter, Russell married Mimi and prepared to leave. Beast asked if he would visit Australia and help Bennett set up the order there. This he did, the cocky sailor finding Bennett “puffed up like a frog with the importance of his recently gained grade of Adeptus Major in the A A

A and IX° in the OTO.”

70

Without a meeting of the minds, they simply traded copies of Crowley manuscripts and parted. Russell arrived back in the United States on January 28, 1922;

71

years later, he would found his own Crowley-derived magical organizations, the Choronzon Club and GBG.

and IX° in the OTO.”

70

Without a meeting of the minds, they simply traded copies of Crowley manuscripts and parted. Russell arrived back in the United States on January 28, 1922;

71

years later, he would found his own Crowley-derived magical organizations, the Choronzon Club and GBG.

Winter rolled in damp and cold, and brought with it the first snow in Cefalù’s history. The unheated villa was miserable, driving Crowley and Leah, dispirited and impoverished, back to Paris that February while Jane, back at the Abbey, sold Crowley’s liquor for spare change. AC again called on the Bourciers at 50 rue Vavin, where they stayed on credit. Unable to muster any enthusiasm, his attempts to recruit new students found no takers. “For the first time in my life, Paris disappointed me,” Crowley wrote. 72

On February 14, Crowley left Paris and returned to Fontainebleau (while Leah returned to London). Here he stayed at Au Cadran Bleu, near the hospital where Poupée had been born, and again confronted the painful memories of his recent losses:

I was so happy and hopeful here two years ago; and now my little Poupée has been dead over a year and her little brother never came to birth; and my manhood is in part crushed. 73

Two years before, he had first been searching for an Abbey. Now he was broken in spirit and wallet. Furthermore, he was facing the ugly truth about himself: despite his philosophy about drug use, he had become addicted to heroin.

Crowley decided to break his drug habit, setting up a progressive method of weaning himself: each day there was a time he called “Open Season,” when he could take as much heroin or cocaine as he wanted. “Closed Season” was the remaining part of the day when drug use was prohibited. His goal was to reduce gradually the length of Open Season until Closed Season was twenty-four hours. He also planned to reduce his heroin intake during Open Season. He began on February 15. He had taken no drug since 8 the previous evening, and only one dose that morning. By 4 o’clock that afternoon, he encountered the Storm Fiend, his name for withdrawal: “The acute symptoms arise suddenly, usually on waking up from a nap. They remind me of the ‘For God’s sake turn it off’ feeling of having an electric current passing through one.” 74 Despite taking a 2 milligram dose of strychnine to help fight withdrawal and eating to reduce his craving, his withdrawal ran the classic course: mucous lined his throat, and the bronchitis that first drove him to heroin use reappeared. He felt emotionally blunt and indifferent. Throughout, Crowley recorded his rationalizations for taking the drug: “A small dose—to show my indifference to these considerations”; “Simply because I feel rotten”; “I felt no craving today, but … I had so much expectation that I took 3 small doses.” 75

While cocaine proved easier to quit, his heroin need persisted. And although he failed to stop heroin altogether, he did substantially reduce his intake. On March 20 he recorded his “triumph over temporal trials.” 76 He was kidding himself in the way any addict rationalizes his or her behavior. Drug addiction would continue to weigh heavily on Crowley’s mind. Over two years later, he would write to Norman Mudd,

I have thought the matter over very thoroughly in the last few weeks, and can give you (at last) a considered judgement.

1 I have never maintained that any man could stop at any time under any condition.

2 Favorable conditions are that a man should a) will to stop, b) know his True Will, c) be able to take steps to carry it out, d) be free from physically depressing stress.

3 I’m all right for a and b. For c I should be all right if I were all right as to d.

4 Given, therefore, that I am safely entrenched at Hardelot or some such place, I think there should be little or no trouble in stopping either suddenly or gradually, as may seem desirable. 77

Yet the same letter contains more rationalization: “a little solid heroin (the first in that form for two months—immediate violent activity) have made me better than my normal good form. I have certainly recovered my drug-virginity; which is clear proof that I can stop at will, the moment physical conditions permit of my throwing a little temporary strain on my constitution.” In the end, it would be the summer of 1924 before his drug addiction was broken.

Back at the Abbey, Jane received instructions from Beast to spend two weeks in a brothel to get a healthy idea about sex. Interpreting this as a great spiritual ordeal, she applied to the local brothel to find the madam only interested in career whores. Undaunted, Jane propositioned la Calce; the landlord, however, had his eye on Ninette and promised to bring by some friends who might be willing. Although he did bring one or two men to meet her, none returned for her favors. Thus Jane, unwilling to walk the streets, resigned herself to failure.

In May, Crowley joined Leah, who was waiting for him in London. Having nothing but £10 and some Highland garb he had put into storage before the war, he pawned his watch and tried to raise money. His first thought was to sell his stock of unsold books. Since Jacobi had published them, however, Chiswick Press had changed owners, and the new company refused to release the books because they found their imprint irregular. Try as he may, Crowley could not convince them to release his books.

He next called on English Review editor Austin Harrison (1873-1928), hoping to get back in touch with London’s editors and sell some manuscripts. Harrison was the same man who had introduced Crowley to Viereck in London before the war and who had rejected Crowley’s “King of Terrors,’ thinking it was an unsubstantiated factual account. 78 Although Crowley was now unpopular in London, Harrison agreed to buy some pieces out of friendship and publish them pseudonymously. Some of them—the centennial article on “Percy Bysshe Shelley,” “The Jewish Problem Re-Stated,” and “The Crisis in Freemasonry”—showed Crowley up on some soapbox or another, but failed to impress. As Michael Fairfax, he offered the poems “Moon-Wane,” “The Rock,” and “To a New-Born Child.” 79 More interesting were two pieces he wrote on his newly enlightened view of drug addiction. “The Drug Panic,” by a London Physician, was Crowley’s attack on the recent Dangerous Drugs Act, which made illegal the sale of drugs to which Crowley was accustomed to purchasing from his local chemist. In a telling autobiographical passage, Crowley complained, “The public is ignorant of the existence of ‘a large class of very poor men’ who would die or go insane if morphine were withheld from them. Bronchitis and asthma, in particular, are extremely common among the lower Classes.…” 80 Crowley had but little experience with morphine; in a 1932 letter he wrote, “I have not touched morphine in any form bar about a dozen minute doses by the mouth in 1917.” 81 He claimed that ignorance inspired the Dangerous Drugs Act and called instead for compulsory education.

Crowley’s article “The Great Drug Delusion” (written under the pseudonym “a New York Specialist”) described his own drug delusion: “Though I obtained definitely toxic results, I was always able to abandon the drug without a pang.” 82 He again advocated legalization of drugs, claiming it would eliminate underground traffic. Toward the end of the article appeared the germ of a new idea brewing in Crowley’s mind:

In the author’s private clinic, patients are not treated for their ‘habit’ at all. They are subjected to a process of moral reconstruction; as soon as this is accomplished, the drug is automatically forgotten. Cures of this sort are naturally permanent, whereas the possible suppression of the drug fails to remove the original causes of the habit, so that relapse is the rule. 83

Of course, AC had no private clinic, and he treated no patients. But he had a theory: that drug use guided by morality and Will was harmless, and addiction occurred from casual or indiscriminate use. While this was not his own experience, it was his interpretation of The Book of the Law ’s “To worship me take wine and strange drugs whereof I will tell my prophet, & be drunk thereof! They shall not harm ye at all.” 84 It worked on paper; he just needed to test it.

On May 24 he met with book publisher Grant Richards (1897–1948) and tried to sell him on a book idea. Richards’s firm had published books by Crowley’s old Le Chat Blanc acquaintance Arnold Bennett, as well as G. K. Chesterton and George Bernard Shaw. Offered Crowley’s autobiography, however, Richards demurred, doubting its marketability. Offered a shocker about drug addiction, Richards again declined, referring him to Hutchinson or Collins. On his way home, Crowley therefore moved on to the firm William Collins. There, science fiction novelist, essayist, and literary advisor John Davys Beresford (1873–1947) liked the idea of a drug shocker. Beresford, who started as an advertising writer, knew Crowley from his days as the editor of What’s On:

We had one remarkable contributor during my editorship, I may add, none other than Aleister Crowley, who was supplying a serial narrative something in the manner of Tom Hood, speckled with problems and puzzles, for the best solution of which a money-prize was offered. 85

Beresford had recently written articles on metaphysical topics for Harper’s magazine. 86 His recommendation, and Crowley’s forthcoming articles in the English Review , convinced Collins to take the book. On June 1, 1922, AC received a £60 advance on the manuscript. He later admitted that, aside from a few chapter titles, “I had in fact no detailed idea of how the story would develop.” 87

Crowley summoned Leah to his side and began dictating immediately. In twenty-seven days, twelve hours, and forty-five minutes, Crowley dictated the entire 121,000-word text of The Diary of a Drug Fiend , a story of wretched pharmacological excess and the redemption of its drug-crazed protagonists by the philosophical code of Thelema. The book is inelegant and unimpressive; but, written in under a month, it was never intended as more than a potboiler. Throughout it appear thinly veiled caricatures of acquaintances and Abbey residents. For instance, Crowley modeled the hero of the story, Pendragon, after Cecil Maitland, who supposedly became an addict at the Abbey. Crowley himself was Mr. King Lamus. Most interesting was the book’s note to Part II:

The Abbey of Thelema at “Telepylus” is a real place. It and its customs and members, with the surrounding scenery, are accurately described. The training there given is suited to all conditions of spiritual distress, and for the discovery and development of the “True Will” of any person. Those interested are invited to communicate with the author of this book. 88

When he wrote “The Great Drug Delusion,” his drug treatment clinic was just a theory. With this manuscript, Crowley prepared to make it a reality.

When Crowley appeared in Collins’s office with the manuscript, the publisher couldn’t believe anyone could have written an entire novel since they last spoke. But there it was on his desk. Impressive. When Crowley asked about his autobiography, Collins considered the offer and paid him a £120 advance on the manuscript. They also offered to publish Crowley’s Simon Iff stories, promising an advance by November 9, but this compilation never materialized.

With the novel completed, Leah returned to the Abbey to recover from illness and to help Ninette, who was pregnant by their landlord. Crowley remained in Paris, visiting friends like writer Jane Burr (b. 1882–1958) 89 and banker-patron of the arts Otto Kahn, hoping to find new students.