CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

The French Connection

Around November 1925, Crowley left Weida and began working on his incisive and inspirational Little Essays Toward Truth

. After a bout of ptomaine laid him up in Marseilles, he attended a party and met Ernest Hemingway, who described him simply as “a tall, gray, lantern-jawed man.”

1

In January 1926, Crowley settled into a villa at La Marsa, Tunis. Jane Wolfe joined him for five months at the beginning of February. At this time, Crowley was also corresponding with a young Tom Driberg (1905–1976), who, at age twenty, was more concerned about finding an artificial stimulant to help him pass his exams than about the Labour Party for which he would later become a member of Parliament.

2

Crowley invited him to Tunis and later to Paris, but their acquaintance was largely confined to correspondence.

While Crowley was in Tunis, Karl Germer took his wife, Maria, on a trip to the Abbey of Thelema. On January 10, 1926, Ninette received them in the empty shell that was once the stronghold of Thelema. Dirty and dilapidated, just about everything had been sold off. The living conditions appalled Germer. Although he stayed at the Abbey until at least February, he joined Crowley in Tunis that April, describing bluntly and exactly the conditions at the Abbey. Although this convinced AC that Lulu, now five years old, should come to Tunis for proper care and education, repeated complications and miscommunications prevented it.

The positive reception of the Mediterranean Manifesto, coupled with the realization that publicity was the key to putting over the Great Work, encouraged Crowley to spend much of 1926 absorbed in his “World Teacher” campaign. “The Only way of getting proper publicity is to arrange for the World Teacher campaign,” Crowley wrote, hoping Evans or someone else with journalistic connections would pick it up. This World Teacher campaign sought to use as its springboard the publicity that Annie Besant and Charles Leadbeater of the TS prepared to introduce the world to Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986), the boy they had groomed to be the next messiah. Theosophy based its concept

of the World Teacher on the Buddhist Maitreya, a future bodhisattva or enlightened being, which Leadbeater equated with Christ. Leadbeater discovered Krishnamurti as a young teenager on the beach of the TS headquarters at Adyar in 1909. Declaring him the vessel for the expected World Teacher, Leadbeater and Besant adopted him and began preparing him for this role. In 1911 the Theosophists founded the Order of the Star in the East to prepare for the World Teacher’s arrival, and in 1926, Krishnamurti began a lecture tour of the United States as this World Teacher. Crowley planned to use the TS’s propaganda to declare himself, not Krishnamurti, the World Teacher. “If this is done as it should be, there is bound to be a big scrap with unlimited stories of excellent news value.”

3

Thus, AC wrote defiantly to Montgomery Evans, “The World Teacher informs the public that Doctor Annie Besant is in error when she states that He will manifest through Mr. Krishnamurti in December, or at any other time.”

4

Characteristically, Crowley was full of unkind opinions:

About Krishnamurti: There is no objection on my part to pæderasty as such. This is a totally different matter. It is the question of the following practice, which I class as black magical because it is unnecessary, uneconomical from the magical standpoint, and likely to arouse highly undesirable forces as being in opposition to the Law of Thelema.

5

On H. P. Blavatsky’s successor, Crowley called Besant “totally devoid of all spiritual greatness, as of moral decency.”

6

The TS was naturally on Crowley’s radar as it influenced every occultist contemporary with Crowley, from Westcott and the rest of the GD to his own students, like Frank Bennett. As strongly as Crowley admired its founder, H. P. Blavatsky, he disliked just as strongly, if not more so, her successors. When Annie Besant introduced Co-Masonry to England in connection with the TS in 1902, Crowley was outraged. This reaction was only exacerbated when Yarker, in his last years, befriended not only Crowley (and thereby OTO) but also Co-Masonry, contributing to its journal and receiving an extensive obituary;

7

likewise when Co-Mason J. I. Wedgwood attended the first meeting to elect Yarker’s successor.

8

When Crowley prepared his commented edition of Blavatsky’s Voice of the Silence

as the supplement to the blue Equinox

, he expected it not only to send tremors through the TS, but to “have the San Francisco earthquake looking like 30¢.”

9

Indeed, at that time Crowley went so far as to draft a manifesto to the TS, declaring himself Blavatsky’s successor; seeking to turn weakness into strength, Crowley even argued (unconvincingly) in his document, “The fact that he has never compromised himself with any branch of the T.S. is highly significant.”

10

Thus Crowley’s current campaign was an expression of his long-standing ideas regarding Theosophy.

Mudd, who was still collaborating with Crowley at this time, would sneak into London’s TS headquarters and pin the Mediterranean Manifesto to their bulletin board. Crowley followed it up with several other broadsheets swiping at the TS. “The World Teacher to the Theosophical Society” read:

The World-Teacher sayeth:

Find, each of you, your own true Way in the Universe, and follow it with eager joy!

There is no law beyond Do what thou wilt!

Do that, and no other shall say nay.

Greeting and Peace!

ANKH-F-N-KHONSU,

the Priest of the Princes.

Next, “The Avenger to the Theosophical Society” was more to the point:

You have done well to protest against the grotesque mummeries of the bottle-fed Messiah; you will still do wisely to beware of its Jesuitical wire-pullers. The attempted usurpation is most sinister Black Magic of the Brothers of the Left-hand Path.

I need not remind you of the shameless and nauseating fraud by which the Grand Old Procuress worked herself into the presidency of your Society, of her blatant attempts to capture various rites of Freemasonry, and her imbecile parodies of the Romish heresy, of the obscene manusturpations practised by Leadbeater on the wretched Krishnamurti, with a view of making him a docile imbecile, in imitation of the traditions of the Dalai Lamas, or of a thousand other duplicities, tergiversations, and crimes. It is your daily shame to remember.

April 1926 saw Driberg distributing these broadsheets for Crowley.

If, as Dorothy Olsen reported, “At last this World Teacher business seems to have caught fire everywhere and we are being interviewed by newspapers and the newspapers seem to be taking it up as quite important news,”

11

they must have been incidental presses since no articles survive among Crowley’s papers. In the end, the campaign fizzled like many of AC’s other grand schemes. Likewise Krishnamurti, it turns out, was uninterested in his spiritual calling, declaring he was not

the World Teacher and precipitating an embarrassing crisis for the TS.

I therefore return Copy No. 2 of your Book, signifying thereby that I revoke all my recognition of you heretofore as Beast, or Priest of the Princes, or as having any authority whatsoever in respect of the Law of Thelema.

13

Karl Germer, who received the unenviable job of selling the American edition of the book, emigrated to the United States with his wife, Maria, on June 12. He checked Crowley’s book stock in Detroit, confirming it was missing. Achad had taken a larger trunk of books to sell in Chicago, but the whereabouts of the second remained unknown. “Achad never handed over the storage checks for us to go seriously into the matter,” Germer recalled.

14

So he got a job, cut back expenses, and sent Crowley the better part of his income to keep the Great Work going: of his $190 monthly salary, he sent Crowley $100.

Although Crowley bought a magical dagger to banish malignant forces and impediments, turmoil nevertheless dogged him. Six days after joining Dorothy and Jane in France that August, he had a major row with Dorothy. As Jane described it in her diary, “Dorothy went on a mad ranting, raving explosion last night which continued until 2:00 a.m.”

15

Two days later, Crowley left for Bordeaux, realizing that Dorothy wasn’t his ideal Scarlet Woman after all. Although she remained his lover for a time, she left England on Crowley’s fifty-second birthday to continue the Great Work in Chicago.

Once again, Beast went on the prowl for a suitable sex-magical partner. He found many candidates, including one Louis Eugene de Cayenne. Crowley’s January 2, 1927, diary entry describes the extent of his quest: “Eugene and all his tribe disappeared, leaving me with nine mistresses in Paris.… I am now eliminating these one by one.”

16

Alas, none of Crowley’s subsequent Scarlet Women would live up to the precedents set by seers like Rose Kelly, Mary Desti, and Roddie Minor, let alone the pillars of strength represented by Leila Waddell and Leah Hirsig.

The most promising contender for the role of Scarlet Woman at this time was K. Margaret Binetti. Crowley met her at the end of August, and despite his promiscuous sex magick couplings, they soon became engaged. Margaret lacked interest in magic and the philosophical rationale behind his infidelity, and this strained their relationship. Crowley soon reconsidered spending his life with the woman to whom he wrote “Lines on being seduced by Madame Binetti.”

17

On February 6, 1927, he burned the talisman of Jupiter he had consecrated for her. “Her callous heartlessness and hypocritical falsity doom her to dire ends,”

18

he recorded in his diary, then cast out his net once again.

Despite the press’s promise, this was otherwise a time of failure for Crowley. Hopfer’s color, diagrammatic revision of 777

was a great idea but would cost an unreasonable $100 per copy. Similarly, plans for a book on the oracle of geomancy,

to sell with a box painted in flashing colors and filled with holy sand from Mecca or Jerusalem, remained just an idea.

Finally, on March 9, a final nail sealed the coffin on Crowley’s Cefalù period. Ninette wrote a letter complaining of her seven years in Cefalù, “Thinking too much, making resolutions and taking oaths, keeping none, violating my better impulses, have worn my nerves to shreds.” Then she bid Jane and Beast “an eternal Adieu.”

19

The Abbey’s financial situation was dire, and although he wired Ninette £500, Crowley realized his dream of a Thelemic community was a lost cause. The best plan was to get Ninette and the children back to France and cut their losses.

AC took her to dinner and, to her surprise, proposed. Four times. He wanted to marry her in Paris the next day. She was too stunned to answer. The next day, having met her daughter Marian, he proposed again. This time, she explained she had to return to Poland (her birthplace had reverted from Austrian back to Polish rule from 1918 to 1939), but promised to return. Crowley wrote to Smith, “I thank you for the galleon of treasure which came under full sail into port here last week. Unfortunately, she has chartered to make more distant shores.”

21

Nevertheless, he hoped to take her to Egypt, where he had had such stunning magical success with Rose.

After graduation, Gerald began to study The Equinox

and Crowley’s other magical writings. He was bright enough to distrust the rumors circulating about Crowley and judge the man for himself, so he contacted Crowley through J. G. Bayley and received an invitation to meet the Master in Paris. What he encountered impressed him immensely: Crowley struck Yorke as a brilliant and talented man with tremendous unrealized potential. His unpublished manuscripts testified to the many important lessons Crowley still had to teach the world … he only lacked a business manager to make a success of his work. Crowley took Yorke’s enthusiasm as an offer and accepted. While The Book of the Law

prophesied a rich man from the west, he found instead a benefactor from Germany and a rich boy from Gloucestershire.

In January 1928 Yorke took the name Volo Intellegere (I will to understand) upon joining the A A

A , and he devoted his spare time to managing Crowley’s finances. He sold his Chinese paintings and ivories to raise money and, that spring, put £400 into a publication account to rehabilitate Crowley’s name and publish his works. From this fund, Yorke paid Crowley a weekly allowance of £10. He also wrote the eight remaining A

, and he devoted his spare time to managing Crowley’s finances. He sold his Chinese paintings and ivories to raise money and, that spring, put £400 into a publication account to rehabilitate Crowley’s name and publish his works. From this fund, Yorke paid Crowley a weekly allowance of £10. He also wrote the eight remaining A A

A members—including Jacobi, Wolfe, Olsen, and Smith—to regularize their membership subscriptions and permit Crowley to continue writing without monetary concerns; of these, only Jacobi regularly contributed $20 a month to the cause, forcing Crowley to rely on the Germers for much of his support. Nevertheless, this permitted Crowley a furnished flat at 55 Avenue de Suffren in Paris.

members—including Jacobi, Wolfe, Olsen, and Smith—to regularize their membership subscriptions and permit Crowley to continue writing without monetary concerns; of these, only Jacobi regularly contributed $20 a month to the cause, forcing Crowley to rely on the Germers for much of his support. Nevertheless, this permitted Crowley a furnished flat at 55 Avenue de Suffren in Paris.

Yorke also paid a typist to copy Crowley’s manuscripts for publication. One of these new projects was AC’s magnum opus, part three of Book Four, Magick in Theory and Practice

. Of this manuscript, Crowley wrote to Yorke:

Montague Summers appears to know what he is talking about. People generally do want a book on Magick. There never has been an attempt at one, anyhow since the Middle Ages, except Lévi’s.

25

Alphonsus Joseph-Mary Augustus Montague Summers (1880–1948), occult scholar, offered a curious contrast to AC. Whereas the latter identified with the infernal trappings of the Great Beast while explicating the holy quest for one’s divine nature, the former was an ordained deacon of the Church of England who specialized in demonology and black magic. Nevertheless the

two men shared a mutual respect. Éliphas Lévi, also cited in the above quote, Crowley claimed as his previous incarnation, and a translation of his book, The Key of the Mysteries

, appeared as a supplement to The Equinox

I(10). Crowley correctly states the literary primacy of his book: whereas Montague Summers, A. E. Waite, and even Francis Barrett (The Magus

, 1801) were primarily purveyors of medieval traditions, Magick in Theory and Practice

was the first modern textbook on the subject in English. How big a market existed for such a book was another matter entirely.

Alas, managing Crowley’s old stock of books was more complicated than Yorke had imagined. While he hoped to inventory these books, Yorke found them scattered around the world: in Chicago with Achad and Olsen, in Naples with Aguel (presumably), in Leipzig with Küntzel, and in London with Pickford’s storage. The latter stock (early works of poetry), he discovered, had been damaged when Pickford’s storage facilities flooded; although Crowley valued these books at thousands of pounds, professional booksellers hired by Yorke estimated that even a good salesperson would be lucky to realize £200 on them. Yorke settled with Pickford’s for the balance of past charges and £40 damages. He then paid the American Express Company to ship Crowley’s remaining works from Naples to Crowley’s Paris address.

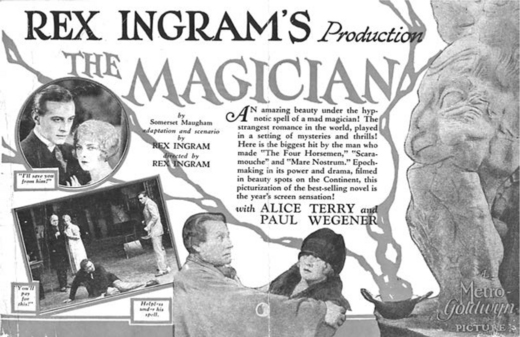

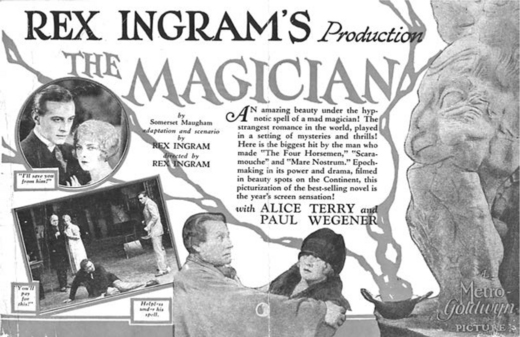

Finally, Yorke kept AC’s pipe dreams in perspective: one such scheme involved Metro-Goldwyn’s film adaptation of Maugham’s The Magician

, which was opening on the Grand Boulevard March 23. Since Crowley received no compensation as the model of Oliver Haddo, he filed an injunction against showing the film. However, when representatives from the film company offered to pay Crowley, he refused. “The lawsuit is a pretext for a business deal,” he explained to Yorke. “I’m holding out for publicity and power.”

26

Crowley wanted a contract to produce a series of educational films on magick. Yorke was pessimistic about the scheme.

I cannot say that I think you will get any damages from Metro-Goldwyn over The Magician

film. Your reputation is too bad to be damaged by that. Nor do I think there is any hope for rehabilitation of character. To my mind, part of your “mission,” if I may use a word I mistrust, is to show that the code of morals of what a Thelemite calls the Old Aeon has been superseded, and that now any act is right provided it is done in the right way, as in interpretation of True Will. It must have been your Will to be the Beast, and a whitewashed Beast is an useless commercial article.

27

He was right: when Crowley could have taken a quick financial settlement, he pushed too hard and got nothing at all from the film company.

Promotional leaflet for Metro-Goldwyn Pictures’ adaptation of The Magician

. (photo credit 17.1)

Kasimira Bass returned to Crowley that spring. While they didn’t run off and marry, they did find bliss together. “She is the one possible magical partner for me, and she is perfect,” Crowley enthused. “Already, despite the greatest difficulties, we have succeeded beyond all my hopes in awakening a current of creative energy of enormously high potential.”

28

Although she began signing her letters to W. T. Smith as 156,

29

she complained that her standard of living fell below the expectations Crowley had given her. While he was used to living hand to mouth with faith that the gods would provide for his needs, Kasimira had no such conviction. “This is her first experience of living under magical laws,” he commented on their finances, “so that the funny little ways of the Gods rather get on her nerves.”

30

They soon began quarreling over money and other petty matters. By June 6, Crowley’s glowing praise of her magical talent declined to “Kasimira is that same cauliflower Ego which destroyed Achad.”

31

With £190 left in the publication fund, Yorke was now pulling out—from his trusteeship and from his editorship. His change of heart stemmed from personal difficulties with The Book of the Law:

The crux of the matter is a) I have tried to accept the Law of Thelema and the New Aeon with you as  [Savior of the Universe], Liber Legis [The Book of the Law]

as the book, and Thelema as the logos. I cannot accept it. Liber Legis

and its claims have bothered me throughout, as it bothered you until it beat you, and I suspect still does.… I cannot therefore support a movement whose sole aim is to spread the teaching contained in Liber Legis

and the commentaries thereon.… Owing to my convictions, therefore, I cannot honestly assist in the practical handling of a publication fund or the raising of money for that purpose.

32

[Savior of the Universe], Liber Legis [The Book of the Law]

as the book, and Thelema as the logos. I cannot accept it. Liber Legis

and its claims have bothered me throughout, as it bothered you until it beat you, and I suspect still does.… I cannot therefore support a movement whose sole aim is to spread the teaching contained in Liber Legis

and the commentaries thereon.… Owing to my convictions, therefore, I cannot honestly assist in the practical handling of a publication fund or the raising of money for that purpose.

32

So Crowley hired Carl de Vidal Hunt (b. 1869) to prepare the public for his book. After becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1895, Hunt settled in Los Angeles,

33

where he became part of the nascent motion picture industry, appearing in such early films as Roaring Camp

(1916), The Marriage of Arthur

(1916), and Jeremias

(1922).

34

While in his mid-fifties, he became a journalist, writing racy human interest stories that were syndicated across America.

35

In Crowley’s employ, he published a story about Hollywood “film mother” Jane Wolfe’s stay at Cefalù as a resident of the “mystery house” run by “Sir Aleister Crowley, high priest of Thelema (oriental philosophy)”:

Sir Aleister, known among his disciples as the “Beast,” is a Britisher, who spent his patrimony in search of the stoic philosophies of the East. He had lived with the Yogis in the silent wastes of India and had published books on the subject. Now he is a wanderer, barred even from his own country—but his friends declare him a genius.

36

When publishers Turnbull became interested in taking Magick

, Crowley gave them a £200 deposit; however, they returned his deposit at the end of October after he refused to let them edit problematic passages.

About this time, Kasimira announced she was getting £3,000 for Beast’s publication fund. Yorke loaned her £200 against a promissory note, but it soon became clear that Kasimira was skimming money off the publication account. Yorke suggested Crowley dump her. AC concurred, writing in his diary,

K. has been acting outrageously for some days. She is stupidly jealous of my talking to Yorke. She sulks and rages without sense. She complains of everything in the most idiotic way. She interferes with every act one does. It is intolerable, save for the Magical Necessity.

I definitely appeal to the Gods to let this Cup pass from me.

37

When Crowley sought a new secretary during the summer of 1928, he wrote Regardie and offered him the job. He dearly wanted it but, as a minor, needed parental permission to obtain a passport. Knowing his parents would never let him study mysticism in France with Aleister Crowley, he told his father he had been invited to study with an artist in England.

He sailed from New York, arriving at the noisy Gare St. Lazare station on the morning of October 12. Through the backdrop of French conversation he heard a distinctly British voice say, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” Regardie turned to face Crowley, tall and pudgy, dressed in blue-gray plus fours. They shook hands—firm, Regardie noticed—then gathered his luggage. They took a taxi to Crowley’s flat, where AC made them coffee in a glass apparatus heated by an alcohol lamp. Thus Regardie, henceforth known as Frater NChSh (Serpent) or Frater Scorpio, became Crowley’s new secretary. He was not yet twenty-one.

In person, Crowley proved to be venerable. He played chess frequently because his phlebitis often kept him homebound. On weekends when Yorke visited, he would set each of them up at a chessboard; then, seated in his favorite chair, smoking a pipe of perique tobacco and warming a snifter of brandy, he would sit with his back to them and call out his moves, playing them both simultaneously. Most amazing was that he usually won.

Crowley spent much of his energy teasing timid Regardie, trying to persuade him to be a bit more outgoing. At one point he suggested Regardie forget about magick altogether and first hit the streets of Paris in order to become acquainted with every human vice. One evening he and Kasimira went out to see the sights of Paris and watch a movie. There, away from Beast’s watchful eye, she confided in him: she was leaving Crowley and wanted Regardie to deliver the message.

Hearing the news, Crowley shrugged and calmly responded, “The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away.” On November 3 he recorded in his diary simply, “Kasimira bolted.” In a candid note to Yorke, he wrote:

Relieved from the strain of Kasimira, I have been able to start serious magick with ritual precautions. The Climax of the first ceremony was marked, as it should be, by the sudden arising of a violent wind; and subsequent ceremonies have been equally notable.

39

Shortly thereafter, the mage was furious to learn that his ex-fiancée had previously been the lover of W. T. Smith, to whom he wrote:

You send me a letter in which you tell me as plainly as anything can possibly do that she has been your mistress. She presents me this letter and imagines that I will not understand anything by it and dismiss the whole thing for weeks and months until, in a burst of confidence, the cat comes out of the bag. I am now looking like Diogenes with a lantern of much greater power to find somebody whose mistress she has not been.

40

A year later, Kasimira Bass would be safe and happy, conducting business in South America, eventually finding her way back to the United States.

By November 8, 1928, Crowley found a new mistress in Nicaraguan-born Maria Teresa Ferrari de Miramar. A dark, short divorcée, she was charmingly convivial despite her poor grasp of English. Crowley called her “marvellous beyond words,”

41

and she certainly made an impression: Jack Lindsay described her as “a fairly well-blown woman, oozing a helpless sexuality from every seam of her smartly cut suit, with shapely legs crossed and uncrossed.”

42

Regardie’s first dinner with the new Scarlet Woman was likewise memorable: while he was busy pondering which utensil was proper to use for which portion of the meal, Crowley fell upon Marie and began humping her right on the floor.

Her magical talents were also remarkable. She claimed to have conjured the devil on four occasions while dancing around bonfires in Nicaragua, and Crowley attested to her abilities shortly after their meeting, “She has absolutely the right ideas of Magick and knows some Voudou.… We did proper ritual consecrations, and arranged for the next Work.”

43

Soon thereafter, AC noted in his diary the consequences of their magical workings:

The Magical Phenomena in this apartment are now acute. Lights and shadows, dancing sparks, noises as of people walking about, a large dark ghost in the bedroom lobby, short attacks of rheumatism (to 3 of us) and a Nameless Fear which seized Regardie.

44

The following day, he also wrote about these manifestations to Yorke:

The phenomena that have taken place in this apartment since the High Priestess of Voodoo [Marie de Miramar] displaced the woman from Samaria [Kasimira Bass] would be quite interesting to the Psychical Research Society, if any of them are not in a coma.

45

Visiting Paris in December 1928, Yorke recounts in his diary an impromptu magical working with Crowley, de Miramar, and Regardie. While Crowley banished and recited the Bornless One invocation, Marie saw visions and did a dance to evoke a fire spirit.

Maria Theresa Ferrari de Mirimar and Aleister Crowley. (photo credit 17.2)

By this point, relations between Hunt and Crowley deteriorated. Hunt, realizing he had his work cut out for him, complained to Yorke of Crowley’s

“dormant, inarticulate, wheezy way of speaking what little he has to say.”

46

Crowley, meanwhile, opined

Hunt’s limitation is that he sees everything in terms of journalism. He is apparently unaware of the existence of the serious occult public. The trouble with him is that he is a cynic. If he could only believe in people and look for noble motives instead of base ones.

47

In Crowley’s mind, Hunt, with his irons in too many fires, was unable to devote enough time to any.

Their business dealings came to a head when Hunt asked Crowley to “fix” the horoscopes of a couple to show them as perfectly compatible. “Hunt was bribed by the Infanta Eulalia, the mother of Don Louis, to arrange a marriage by which her son should get about £24,000 a year settled on him for life,” Crowley recorded;

48

to Hunt’s displeasure, he refused to sell the Great Work. Before long, Crowley stopped paying him altogether.

Hunt promised dire consequences if AC did not pay his salary. “It is a type of blackmail well known in France,” Crowley scoffed,

49

and his friend Gérard Aumont concurred. Yorke also noted, “Hunt had written me what AC interpreted as a blackmail letter. It probably was the first step towards blackmail.”

50

Nevertheless, Hunt took a stack of Crowley’s news cuttings and the manuscript of Mortadello

to the Prefecture. He also told the official that Crowley had been questioned regarding rumors that he had strangled three women in Sicily, and asked the authorities to look into the matter.

In response, Crowley alleged that Hunt had stolen his employer’s personal property, i.e. the manuscripts. Furthermore, AC argued, Hunt showed bad faith by going to the police with papers entrusted to him as Crowley’s agent. “His first capital was the pennies he stole off his dead mother’s eyes,” Crowley said.

51

As with his Metro-Goldwyn stunt, Crowley wasn’t out to ruin Hunt as much as he hoped to drum up publicity for Magick

.

Learning of this conflict, Yorke was furious. He had planned to sink a fortune into printing Magick

, and now AC threatened to ruin it with a spate of bad publicity. He fired off a virulent criticism:

you are a bloody, not a divine, fool in attacking Hunt. To start with, he was not in our employ when he sent those papers to the Prefecture. He told me at the time, and wrote to me afterwards, that he honestly thought it was impossible to help you, as you would not play up to the necessary parlour tricks, and that your past reputation was too much of a good thing. He could not, therefore, continue to take your money. He introduced you to good people, and can make a good showing that he worked for you. It was my honest opinion at the time that he was doing his best, and I wrote and told him so at the time.

52

Such blunt exchanges typified the Crowley-Yorke correspondence from this period. Referring to The Book of the Law

ii.59–60, Yorke said their dealings

should “Strike hard and low” when they disagree; if they were kingly men, brutally honest words would not hurt them.

I wrote to my uncle, and he said that I am old enough to choose for myself. I will give you certain books to read, he said, and they will help you think. So I read parts of them. After all, an author’s work is a part of himself. So I have judged him by his own works and what could be fairer? But the answer is no. I really have no time to spend on a man so rude or conceited. His works are a part of him and I am very sorry for the other part. What a hash he has made of it.

53

Her polite refusal must have been a disappointment for Crowley, who so desperately wanted a family. A few years later, on June 9, 1934, she would marry boot and shoe operative Frank Hill; she would outlive her husband, dying of a myocardial infarction at Battle Hospital, Reading, on March 9, 1990.

54

She would never reconcile with her father.

At age twenty-seven, Yorke became director of both Mexican Railways and H. Pontifex & Sons. He offered £800 toward the publication of Magick in Theory and Practice

with a promise of another £1,000. By the end of December, Lecram Press of Paris agreed to take the job. Crowley soon had an estimate in hand and a prospectus in press. He also decided on the book’s format: “By issuing Magick

in four parts,” he told Yorke, “we save 12% buying tax.”

55

AC believed this publication had set a powerful magical current into motion. Looking at the turmoil in his life—Kasimira leaving, Hunt threatening, plus minor events like Regardie getting sick and Marie becoming paranoid—he saw himself under magical attack. His most important works always met with difficulty going to press.

Having departed for Fontainebleau on Friday afternoon, Mdme de Miramar went forth for her own base purposes … I think to the cinema … on Saturday afternoon. She was followed, I understand, more or less from the house or its vicinity by Mrs. Bass. At any rate, Kasimira took her seat beside Mdme de Miramar on the omnibus, accosted her, and began a sort of cinema Roman conversation. She was evidently quite furious at having lost her last chance in life.

56

Fearing Kasimira might throw sulfuric acid on her, Marie ran. It convinced Crowley that Kasimira was plotting against him with Hunt.

Domestic worries continued as an ailing Regardie entered the hospital. On January 13, 1929, he was back home again, but would soon thereafter contract gonorrhea from a prostitute.

The inspector rattled off a series of disconnected questions for Crowley to answer: why did Regardie lack a carte d’identité

(identification card)? Why did people refer to Crowley as the King of Depravity? Taking keen interest in Crowley’s Bunsen-powered coffee machine, he asked if it was a drug distillery. Did he take drugs? Was he ever expelled from the United States? Did he write pro-German propaganda during the war? Was he the head of a German occult organization? Was he actually a German spy?

Crowley did his best to set the inspector straight. This wasn’t the first time the authorities got him wrong. As he recounted at this time,

We have a very valuable witness in Aumont.… I once gave a little tea-party at the Tunisia Palace Hotel, and somebody brought him along as interested in literature. Within a few hours the police called upon him, and asked him if he knew who he had been having tea with, because it was a man who had strangled three women in Sicily.

57

The nature of these questions, however, demonstrated that Crowley’s colorful reputation was finally catching up with him. Where had he lived for the past year?

“I have a friend here in France,” Crowley answered, “Dr. Henri Birven, who calls me the Patriarch of Montparnasse. I first went to Montparnasse in 1899 and settled down there in 1902. Since that date, I have lived constantly there.” Crowley paused and looked at the inspector askance; “the only exceptions being when I was elsewhere.”

58

Referring to his diary, Crowley gave the Inspector the address of every hotel he had stayed at for the last year, plus the date and hour of his every move.

Wearied by details, the inspector moved on. “People come to consult you. And what do you advise them to do?”

“That depends entirely upon the questions. My sheet anchor is common sense. In any case, I should not advise them to do anything against the law, which I honestly respect as far as it will allow me to do so.”

“And how much are you paid for your advice?”

“I take no money for consultations.”

He was incredulous. “None?”

“None.”

“Do you tell fortunes?”

“No.”

Stumped, he moved on to the kabbalah.

“It takes seven years of uninterrupted study to even begin to know about it,” Crowley answered. To the bewilderment of the Inspector, he launched into a long disquisition on the kabbalah.

After a while, the inspector commented, “For the first time in my life, I don’t understand at all what is being said to me.”

Crowley smiled. “This is very natural: I have been spending over fifty years trying to make myself clear, but nobody seems to benefit by my endeavors.”

59

At that, the inspector became polite. When he concluded the interview, he seemed satisfied that Crowley was a decent man.

But on February 15, Crowley learned that the authorities had declined to renew his identity card, issuing a refus de séjour

despite his frequent visits since 1920. The news came as a shock, and Crowley searched for a reason: that idiot inspector thought his coffee machine a cocaine distillery; or that miscreant Hunt cried to his government contacts because Crowley refused to falsify those horoscopes to cement an arranged marriage; or perhaps Regardie’s sister, worried about her brother’s welfare, had asked the authorities to intervene. Perhaps all of these played a role. When Paris Midi

reported Crowley had been expelled—not merely having his identity card renewal denied—for being a German spy using OTO as his cover, matters only became worse.

Crowley wrote to the British Embassy, but they would not intercede on his behalf.

60

He then wired Yorke to come over and help clear up the mess. Yorke, reluctant to have himself or his family dragged into the incident, declined. Instead, he urged AC not to start any trouble.

Crowley called Yorke a coward, unwilling to stand up for truth and decency. He was also foolish to think he could hide from the press. If he didn’t rise up indignant, he would only look guilty. No, Crowley decided, he would rather defy the order, stay in Paris, and wind up in prison rather than buckle under and leave. If the government was going to arrest him, they’d have to press charges and prove

he had done something wrong, which he hadn’t. It was a Mexican standoff. The story and its newspaper coverage made Crowley a sensation in Paris … just the thing to generate brisk sales for Magick

.

At the time this bombshell fell in Crowley’s lap, he was sick with a cold. Paris’s winter of 1929 was damp, shrouding the countryside with rain, snow, and frost. A week after the refus de séjour

, Crowley was so ill he spent the next five days in bed. Owing to illness, authorities allowed him to stay in France until he recuperated—which, Crowley planned, would not happen until he saw Magick

through its publication.

Meanwhile Regardie, fingered as an associate of Crowley’s, and Marie, also lacking a valid carte d’identité

, were asked to leave the country. The police told Marie they were doing her a service by separating her from Crowley. On

March 9 Regardie and Marie left for England, only to be refused entry because Marie was neither a citizen nor possessed of a visa. Turned back, France denied them entry, forcing them to go to Belgium. They arrived in Brussels on March 11. Holed up in a foreign nation, Marie took advantage of the naive Frater Scorpio and seduced him.

While Regardie spent the next weeks worrying what Crowley would do when he found out, Beast was performing sex magick with a woman named Lina “to help deM[iramar] out of her trouble.”

61

He spent his remaining time correcting proofs of Magick;

on April 12 he held an advance copy of the book, his first major publication since the blue Equinox

a decade earlier. Crowley spent his last day in Paris speaking to reporters and being photographed. He left France on April 17 satisfied Magick

would appear as scheduled.

Aleister Crowley at the time he left France in 1929. (photo credit 17.3)

Paris Midi

had company in taking up his story. As he recorded in his diary, “Articles going on by the dozen. Hear that U.S.A. has already had lots of wild fables.”

62

On April 17 the New York Times

ran the headline “Paris to Expel A. Crowley.” On April 21, Reynolds Illustrated Newspaper

published an interview with Crowley, who expressed bewilderment at his treatment. “There is no accusation against me,” he told the reporter:

My sweetheart was expelled.… When she demanded what it was the French authorities had against me they suggested that I was a trafficker in cocaine. This is ridiculous. Afterwards, they said: “It is not that. Perhaps that is not true. It is something else. The real reason is too terrible.”

63

Meanwhile, back in England, John Bull

gloated:

Soon Hell will be the only place which will have you. You were driven out of England, America deported you and so did Sicily. Now France has given you marching orders. Since I exposed you for the seducer, devil doctor and debauched dope fiend that you are, not a decent country will tolerate either you or your sinister satellites.

64

Crowley arrived on June 11 for dinner with Colonel Carter. They apparently got along well, for Crowley noted in his diary, “All clear” and thereafter referred to him as “ol’ Nick” and “Saint Nicholas.” Thereafter the two met occasionally for dinner.

While in London, Crowley visited some of his acquaintances, including Gwen Otter, Montgomery Evans II, and linguist Charles Kay Ogden (1889–1957). Observer

art critic Paul George Konody (1872–1933) expressed interest in Crowley’s work, encouraging him to paint. Thus when James Cleugh, literary director of the Aquila Press, mentioned that the press was for sale, Crowley planned to buy it, turn it into a gallery, and charge artists to exhibit their works. Major Robert Thompson Thynne, whom he met at this time, promised to help with the scheme. And although he still planned to sue John Bull

, a publishing contract and £50 advance from the Mandrake Press distracted him.

The Mandrake Press was a small publishing house run by Edward Goldston (1892–1953) and Percy Reginald Stephensen (1901–1965). Goldston was an enterprising businessman who went from working in the Oriental department of Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Company to running his own rare bookstore

and publishing house on Museum Street. Both his clients and his books were rich—in 1925, for instance, he bought and sold the vellum Melk monastery copy of the Gutenberg Bible—and Goldston shrewdly reinvested his profits into other private presses. Jack Lindsay (1900–1990), who sought a publisher for D. H. Lawrence’s artwork, united Goldston with Stephensen to form the Mandrake Press. Stephensen, an Australian nicknamed Inky, was

a thin and immensely energetic young man, with a sandy moustache, fierce, keen eyes and a quick, nervous manner. He was a Rhodes scholar at Oxford, where his views were rarely exactly coincident with those of the university authorities.

67

In his school days, he had been a staunch defender of Communism. He later married but continued to spearhead various causes. In his native Australia he operated for a time the Fanfrolico Press, and this background made him an ideal business partner for Goldston.

Mandrake made a big splash by publishing and exhibiting Lawrence’s paintings at their 41 Museum Street offices: the authorities had already suppressed his Lady Chatterley’s Lover

, and after newspapers attacked the exhibition, the police raided the show and seized any artworks that showed pubic hair or genitalia—about half the pieces. The final trial, held on August 8, ended with Mandrake returning the paintings, stopping the exhibition, and destroying the books; however, no charges were pressed. Although losing Lawrence’s book struck the small press hard, it also gave Mandrake a sensational launch. Through the publicity, Mandrake signed twenty new titles between June and August.

Stephensen, in the midst of a battle against censorship, was eager to take on a dark horse like Crowley. A controversial figure whose theories of sexual liberation were sure to outrage the prudes who attacked the Lawrence exhibit was just what he wanted. The press offered to publish The Stratagem and Other Stories

and talked of exhibiting his paintings. On June 28, AC signed a contract and received his £50 advance. He would use it to rent a cottage in Knockholt, Kent, which he would occupy that fall. Stephensen had found it for him; it was thirty miles south of London and separated from Stephensen’s own weekend place by a household of elderly spinsters.

Returning to work brought new problems. One of them emerged from Crowley’s visit to Germany, where he permitted Birven, who was publishing the magical magazine Hain der Isis

, to serialize a German translation of parts of Magick

, as well the entirety of his article “The Psychology of Hashish” … in violation of his Mandrake contract. Meanwhile, Yorke, Goldston, and Stephensen all agreed that Crowley needed to change the names of Moonchild

’s characters, which AC had modeled after real-world people such as Yeats, Mathers, and Desti, before they could publish it. Finally, on August 29, Crowley instructed Lecram Press to send the copies of Magick

to Mandrake for distribution; however, December would arrive before the books.

Nevertheless, Mandrake soon released new Crowley titles. The Stratagem and Other Stories

came out September 10, followed on September 25 by Moonchild

, which boasted a dust jacket by artist Beresford Egan (1905–1984). Mandrake also released another book of lesser interest to the Crowley corpus: not only did Merry Go Down

by Rab Noolas contain poetry by Victor Neuburg but Noolas was a pseudonym for Philip Heseltine, better known as Peter Warlock (1894–1930). He was one of Stephensen’s drinking buddies who had helped with the Fanfrolico Press.

The public eye also beheld Crowley in Betty May’s biography, Tiger Woman: My Story

. Published by Duckworth in 1929, it identified Crowley only as “The Mystic,” painting a kind picture of him. Most significantly, the book stated that Raoul died not from drinking cat’s blood during a ritual but from contaminated water. When he lunched with Duckworth’s representative Anthony Powell (1905–2000) one afternoon, Crowley complained just a bit about Tiger Woman

, his main gripe being the hard life of a magician. Powell would model Dr. Trelawney of his acclaimed twelve-volume novel sequence Dance to the Music of Time

(1951–1975) after Crowley.

Marie, meanwhile, became difficult. The new Mrs. Crowley drank heavily, and her suspicious nature blossomed into rabid paranoia. The day before their move to Knockholt, she had made a scene; then, the day after they moved, Crowley recorded in his diary that Marie “had several bad attacks of delusion.”

Two days later, during Crowley’s fifty-fourth birthday party with the Germers and Stephensens, “Marie relapsed badly in P.M. & there was a most nerve-wracking scene.”

68

When, shortly thereafter, Marie worsened and began having fainting spells, Crowley sent her to a nursing home. “Seven hours’ rest worked wonders,” he noted.

69

Crowley’s luck with women was again showing.

Regardless, that October was important as the press got hold of Crowley’s newest books. While the Birmingham Post

panned The Stratagem and Other Stories, Moonchild

met with mixed reviews. The Aberdeen Press and Journal

called it “one of the most extraordinarily fantastic yet attractive novels we have read,”

70

while the New Statesman

expressed perplexity, writing, “Possibly the author may know what this nonsense is all about.”

71

Finally, the New Age

slammed its sensational jacket blurb:

I had no idea that Mr. Crowley was one of the “most mysterious” of living writers, or even that he was mysterious. What does it mean, anyway? That he writes mystery novels? That it is a mystery why he writes novels? That no one knows who he is? Or what?

72

Mandrake also released Crowley’s autobiography. Although the author titled it The Spirit of Solitude

, Stephensen “re-antichristened” it The Confessions of Aleister Crowley

after St. Augustine’s autohagiography. It was so long that Mandrake planned to issue it in six volumes. The October 1929 invoice for volume one cited printing costs of £167. The book was handsome, bound in oversize white buckram, and sold for two guineas.

Unfortunately, October 1929 was the worst possible month to release expensive, privately printed books, for the stock market crash on Black Friday, October 28, meant slow book sales. Furthermore, the Germers lost a lot of money on the stock market, making support of Crowley more difficult.

Stephensen attributed the difficulty in selling Crowley’s books to his anonymity, which exceeded his notoriety. Since Mandrake had such success with its D. H. Lawrence exhibition, he planned to show Crowley’s artworks. When Goldston skeptically refused to fund the exhibit, Crowley’s people paid to ship and frame his paintings with reimbursement from Mandrake pending a successful show. On Friday, November 1, starting at 10 a.m., the public could pay £1 to see AC’s artwork at the Mandrake offices. With many of Crowley’s works remaining soiled and unframed, it was disappointing and, unlike the Lawrence exhibit, generated no interest.

Goldston, convinced of Stephensen’s folly, finally closed the Mandrake offices for the winter. Among Mandrake’s last official actions that December were releasing Volume Two of the Confessions

, working on Volume Three, and transferring three thousand unbound copies of Magick in Theory and Practice

to England for distribution. This last book was supposed to bear a talisman on its cover, but no engraver would take on so ignominious a task; but the four paperbound volumes did include a color plate reproducing the talisman.

A

A , and he devoted his spare time to managing Crowley’s finances. He sold his Chinese paintings and ivories to raise money and, that spring, put £400 into a publication account to rehabilitate Crowley’s name and publish his works. From this fund, Yorke paid Crowley a weekly allowance of £10. He also wrote the eight remaining A

, and he devoted his spare time to managing Crowley’s finances. He sold his Chinese paintings and ivories to raise money and, that spring, put £400 into a publication account to rehabilitate Crowley’s name and publish his works. From this fund, Yorke paid Crowley a weekly allowance of £10. He also wrote the eight remaining A A

A members—including Jacobi, Wolfe, Olsen, and Smith—to regularize their membership subscriptions and permit Crowley to continue writing without monetary concerns; of these, only Jacobi regularly contributed $20 a month to the cause, forcing Crowley to rely on the Germers for much of his support. Nevertheless, this permitted Crowley a furnished flat at 55 Avenue de Suffren in Paris.

members—including Jacobi, Wolfe, Olsen, and Smith—to regularize their membership subscriptions and permit Crowley to continue writing without monetary concerns; of these, only Jacobi regularly contributed $20 a month to the cause, forcing Crowley to rely on the Germers for much of his support. Nevertheless, this permitted Crowley a furnished flat at 55 Avenue de Suffren in Paris.

[Savior of the Universe], Liber Legis [The Book of the Law]

as the book, and Thelema as the logos. I cannot accept it. Liber Legis

and its claims have bothered me throughout, as it bothered you until it beat you, and I suspect still does.… I cannot therefore support a movement whose sole aim is to spread the teaching contained in Liber Legis

and the commentaries thereon.… Owing to my convictions, therefore, I cannot honestly assist in the practical handling of a publication fund or the raising of money for that purpose.

[Savior of the Universe], Liber Legis [The Book of the Law]

as the book, and Thelema as the logos. I cannot accept it. Liber Legis

and its claims have bothered me throughout, as it bothered you until it beat you, and I suspect still does.… I cannot therefore support a movement whose sole aim is to spread the teaching contained in Liber Legis

and the commentaries thereon.… Owing to my convictions, therefore, I cannot honestly assist in the practical handling of a publication fund or the raising of money for that purpose.