At fourteen, Petr Ginz wrote the equivalent of a captain’s log on a sinking ship: daily reports about the weather and accounts of the general situation and everyone’s activities. He does not mention feelings of fear, powerlessness, sadness, or pain. But they are heavily present in what is left unsaid. Translation usually means to render, faithfully and convincingly, all the nuances of an author’s voice—the words, the tone, the rhythm. In the case of Petr Ginz’s diaries, it was equally important to capture, or at least hint at, the grave silence surrounding his brief entries.

But not all his writing in this book is of the same succinct quality. Petr Ginz was an extraordinary boy—artistic, inventive, creative, observant, very mischievous, and witty. He was extremely well informed about what was going on in the world at large and in his own environment, and, like the real writer he might have grown into, from time to time broke out of his concise style and allowed his feelings and opinions to find expression in a poem, story, or essay. There is a long poem about the humiliating Nazi laws Jews were forced to accept, which satirizes in the sharpest manner not only the absurdity of the rules themselves but also the Jews’ ability to live with them. There is a heartbreaking poem, written as an adolescent in Theresienstadt, about his feelings for the home and life he has lost in Prague. His articles and stories, written for the magazine he edited in Theresienstadt, reflect a unique ability to transcend the environment of a concentration camp and to focus instead on a rich inner world of spiritual and moral values. Everything he wrote was pointing to a future full of excitement and discovery.

The most difficult passage to translate was his description of the day he found out about his own transport, written in Theresienstadt, from memory. Characteristically, it consists not of an emotional outpouring but mostly of a precise description of the work involved in cleaning typewriters, a job he was doing at the time. As I searched for all the right technical terms and even laughed at the pranks he teased his managers with, I understood and felt the acute necessity to concentrate on mundane reality even as it was crumbling all around him, and under his own feet. But the fourteen-year-old Petr Ginz had no illusions: “So I went home. While walking, I tried to absorb, for the last time, the street noise I would not hear again for a long time (in my opinion; Father and Mother were counting on just a few months).”

As a translator, I felt I was watching this boy grow from a child (whose daily life in Prague went on in places so familiar to me from my own Jewish childhood there, many decades later) into a young man, his writing style changing accordingly. But not his voice, which never wavered in its maturity and astonishing self-control. I hope this translation also captures the man in the boy, the extraordinary man he would have become had he been allowed to live.

—Elena Lappin

London

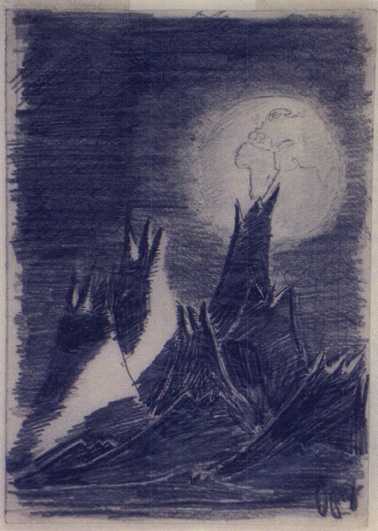

Petr Ginz (1928–1944), Moon Landscape, 1942–1944, pencil on paper, 14.5 × 21 cm; Gift of Otto Ginz, Haifa; Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem.