Chapter Three

For a couple of days Harriet saw nothing of Wiz.

From her window she could spot the occasional rabbit in the valley below, but she saw no hare, European or Partian. She rode over the farm on Breeze, now and again calling, ‘Wiz! Wiz!’ but no-one answered.

‘Wish you could talk like he does,’ she said to the pony. ‘We could have ever such interesting conversations,’ and Breeze blew a bubbly snort of agreement.

‘At least,’ said Harriet, ‘I can tell you all about Wiz. That’s not breaking my promise to him, because although you can understand a lot of things I say, I doubt if a magic hare from outer space would mean much to you. And I can’t talk about it to Dad, or Mrs Wisker the cleaning lady, or the postman, or the vet, and I haven’t got a mum to tell even if I could. I wish I did – have a mum, I mean. It must be nice.’

That evening, when her father came up to say good-night to her, Harriet said ‘Dad. D’you think you’ll ever get married again?’

Her father sat down on the bed.

‘Would you be pleased if I did, Hattie?’ he said.

‘Well, yes, I suppose so. If it was someone you liked.’

‘Only liked?’

‘Well, loved then.’

Harriet’s father took hold of her hand and with one finger idly tickled the palm of it, just as he used to when she was little and he played ‘Round and round the garden like a teddy bear’ with her.

‘I don’t honestly think it’s very likely,’ he said. ‘Just because Mummy’s not here any more doesn’t mean I’ve stopped loving her. And anyway, I don’t meet anybody much, do I?’

‘No.’

‘I don’t like to think of you being lonely.’

‘I’m not a bit lonely,’ said Harriet. ‘I’ve got you and Breeze and Bran and all the other animals.’

She yawned.

‘And Wiz,’ she said sleepily.

‘Who’s Wiz?’ said her father.

‘Oh,’ said Harriet. ‘Oh . . . that’s my nickname for Mrs Wisker.’

Mrs Wisker was a stout middle-aged widow, a thorough cleaner but not the world’s fastest worker.

‘Funny name for her,’ said Harriet’s father. ‘You don’t call her that to her face, do you?’

‘Oh no,’ said Harriet. ‘She might not like it. But I like her – she’s nice isn’t she?’

‘Perhaps I’d better marry her then?’

‘Oh, Dad!’

That night, Harriet dreamed about Wiz. He had somehow climbed up to her bedroom window and come in.

When she woke, she got out of bed and leaned on the windowsill to scan the valley below, but it was hareless.

There was a house martin’s nest in the eaves just over her window, and she watched one of the parent birds returning from hawking insects. It swooped up with a beakful, just a metre or so away from her face, and she could hear the cheeping of the hungry youngsters in their cup-shaped nest of mud above.

As the martin wheeled away again, a sparrow fluttered out of the creeper on the house wall and landed on the sill, right beside Harriet, and chirped at her.

‘Cheeky thing!’ she said, expecting it to fly off at the sound of her voice so close. But instead it flew past her into the room.

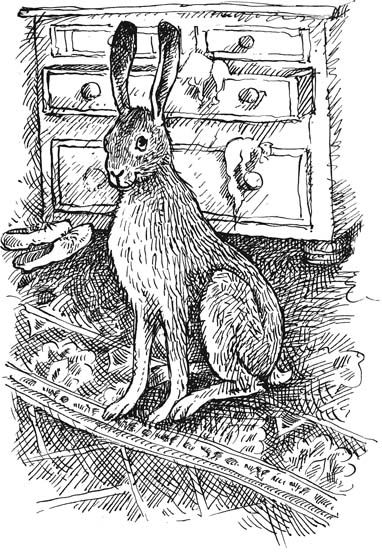

Harriet turned round, to see the hare sitting up on the bedroom carpet. Of the sparrow there was no sign.

‘Wiz!’ cried Harriet. ‘How on earth did you get here?’

‘Not so much on earth as off earth!’ said the hare. ‘I flew.’

‘You were that sparrow? You changed into it?’

‘And back again, I’m glad to say. I don’t think I much fancy being Passer domesticus.’

‘More Latin?’

‘Yes.’

‘But you’ll have to fly out again. You can’t just jump out of the window.’

‘True. But next time I think I’ll be a less ordinary bird. In the meantime, how are you, Harriet?’

‘Quite well, thank you,’ said Harriet. ‘And you?’

‘I’m really rather enjoying my holiday on Earth,’ said Wiz. ‘It’s a lovely bit of country, up here on the Wiltshire Downs. Very different from Pars.’

‘What’s Pars like?’ asked Harriet.

‘Absolutely flat. Not a hump nor a hollow anywhere. That’s why I like it here. And I like being a hare too – it’s fun. We Partians are slow movers, but now I can run like the wind.’

‘Have you come across any other hares?’ said Harriet.

‘Since you ask, Harriet,’ said Wiz, ‘I did meet a rather attractive young doe.’

‘Did you speak to her?’

‘Of course.’

‘Not in English?’

‘No. In Leporine.’

‘Oh. So you can speak animal languages as well?’

‘Certainly.’

In the yard below, Bran barked.

Harriet looked out of the window to see her father and the dog setting out to fetch the herd for milking.

‘Well then, what’s Bran saying?’ she asked.

‘He’s saying a number of things,’ said the hare. ‘One is a message to the cows, that he’s on his way. One is a greeting to your father, that he’s glad to be with him. And one is just a general expression of well-being: “It’s a lovely morning and I’m a healthy, happy old dog who’s glad to be alive!”’

‘You can’t tell all that from a bark,’ said Harriet.

‘Oont,’ said the hare.

‘Oont?’ said Harriet. ‘What does that mean?’

‘It’s a Leporine word,’ said Wiz. ‘A sort of mild protest. In this case it means, “Surely, Harriet, you don’t think I’d lie to you?”’

‘Actually, I don’t,’ said Harriet. ‘I believe everything you tell me, Wiz. And by the way, I’ve got something to tell you. Dad’s going to combine the wheat today.’

‘In that case I must remember to make myself scarce,’ said the hare, ‘but before that I’d better make myself into something else. Let’s see – how about Carduelis carduelis?’

‘What’s that?’

‘Have a look in your bird book.’

Harriet took down from her shelves A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe, and looked in the index.

‘I’ve found it!’ she cried after a bit. ‘It’s a goldfinch!’

‘Switt-witt-witt-witt!’ piped a voice in reply, and there, perched upon her bedrail, was a beautiful little bird with a head of scarlet, black and white, and black and yellow wings, as colourful as the sparrow had been drab. For a few seconds it fluttered before Harriet’s face as though bidding her goodbye, and then it flew out of the window and away.

Watching, Harriet saw the goldfinch alight among a large patch of thistles in the home paddock and disappear amongst them. A little later, if she had not turned away to get dressed, she would have seen a hare come out of the thistle clump and lope off down the trackway.

After breakfast, when her father had gone out to clean the parlour and yards, Harriet was washing up when Mrs Wisker arrived. Always she made the same remark.

‘Puffed I am,’ she said, ‘pushin’ that old bike up the hill. But then, ’tis lovely freewheelin’ down again.’

‘We’re going to cut the wheat on the Ten Acre today, Mrs Wisker,’ Harriet said.

‘Are you now, my duck? You goin’ to ride on the combine?’

‘I expect so. To start with anyway.’

‘Rabbit-pie then, eh?’ said Mrs Wisker.

‘I wish he wouldn’t shoot them really,’ said Harriet. ‘I think I might be a vegetarian when I grow up.’

‘Bad for you that is,’ said Mrs Wisker, ‘doin’ without meat. I likes my meat. A nice fat rabbit. Or a hare. Now a hare’s lovely, my late lamented hubby always said, provided you let it get a bit ripe.’

Harriet shuddered.

‘Some people say that hares are witches,’ she said.

‘Course they are, duck, everybody knows that,’ said Mrs Wisker, ‘but that don’t stop me eating one if I gets half a chance.’

‘But you believe in magic, do you, Mrs Wisker?’

‘Course I do. Anyone with any sense does, stands to reason. Even my late lamented hubby did and he hadn’t no more sense than an old sheep. How else are you goin’ to account for that old circle in your dad’s wheat? Got to be somethin’ funny about that.’

‘You don’t think it’s due to natural causes?’

Mrs Wisker gave a loud piercing shriek, the sort of noise someone makes while being murdered, but Harriet knew it was only her way of laughing.

‘Natural causes, duck?’ she cried. ‘Not on your nelly! ’Tis spaceships as makes ’em, I reckons. UFOs, some do call ’em, but I calls ’em UHTs.’

‘UHTs?’

‘Unnatural Heavenly Things!’ said Mrs Wisker with another ear-splitting screech.

Later that morning, once the dew was off, combining began on the Ten Acre. A neighbouring farmer came with his tractor and trailer to help haul the grain away, while Harriet’s father drove the combine harvester and she stood beside him on the platform.

At first she could see one or two rabbits moving about in the shelter of the corn, but she knew that it was not until the still uncut square of wheat became quite small that they would begin to break from cover and make a run for it across the stubble.

‘I don’t want to see you shoot them, Dad!’ she shouted above the roar of the machine. ‘I don’t like it. Let me get down and go home.’

Thank goodness I remembered to warn Wiz, she thought as she walked up the hill, hearing behind her an occasional bang. Though of course if he had been in the wheat, he could always have changed himself into something else – a mole perhaps, that would burrow down into the ground out of harm’s way.

All the same, after the combining was finished, she had to nerve herself to ask her father if he had shot anything.

‘Couple of bunnies,’ he said.

‘Was that all?’

‘And a hare.’

Despite herself, Harriet felt a cold shiver of fear.

‘Was it a buck or a doe?’ she said. Say it was a doe, please, she thought.

‘It was a buck. A big jack-hare. Though I don’t see what odds it makes. Either way it’ll taste the same.’

Harriet made herself go and look at the three bodies hanging, heads down, in the scullery – two grey, one tawny. By the side of the rabbits, the dead hare looked very long. Its ears hung limply down and there was dried blood on its nose.

It can’t be Wiz, she thought.

It can’t.

Can it?