Chapter Five

A little lane ran through the bed of the valley – a lane that led to nowhere except Longhanger Farm – and Harriet now heard a car coming along it and changing down for the sharp turn into the farm trackway.

At the sound of it, Wiz loped off and Harriet climbed back over the fence. The car stopped by her, and a woman put her head out of the window and said, ‘Excuse me, but do you have any hens?’

‘Yes,’ Harriet said.

‘I wonder if you could sell me a dozen eggs?’

‘Well, we just keep them for ourselves,’ said Harriet, ‘but I expect I can find you a dozen. They’re laying quite well at the moment.’

‘That’s very kind of you,’ said the woman, smiling. ‘What’s your name, by the way?’

‘Harriet Butler.’

‘OK, Harriet, you run ahead and I’ll meet you up at the farm.’

‘Who was that, Mrs Wisker?’ said Harriet when the woman had paid for the tray of eggs and driven away again.

‘New,’ said Mrs Wisker. ‘Bought the old turnpike cottage, t’other side of the village. Married woman, she is.’

‘How d’you know?’

‘Got a big old gold weddin’ ring on, hadn’t she?’

‘I didn’t notice,’ Harriet said.

‘I did!’ said Mrs Wisker with a shriek. ‘There’s not much I don’t notice, my late lamented hubby used to say. And I’ll tell you another thing I knows about her too.’

‘What?’

‘She likes an egg for her breakfast,’ said Mrs Wisker, screaming yet more loudly.

‘Here’s one pound fifty, Dad,’ Harriet said when her father came in at lunchtime.

‘What for?’

‘Eggs. I sold a dozen to a lady who came. They’ve bought the old turnpike cottage, Mrs Wisker said.’

‘Perhaps we should get a few more birds,’ said her father, ‘and then you could earn yourself a bit of pocket money, selling eggs.’

‘But you pay for all the food.’

‘But you do all the work. Here, have this money back for a start.’

‘Look what I’ve got!’ said Harriet to her hare when she met him as she rode on the downs that afternoon.

‘Money!’ said Wiz. ‘The root of all evil.’

‘Well, everybody needs some,’ Harriet said.

‘Hares don’t.’

‘But you must have money on Pars?’

‘Oh yes. But we treat it sensibly. Here on Earth some human beings have so much money they don’t know what to do with it, and some are desperately poor. On Pars everyone’s equal. Much fairer.’

‘Are you looking forward to going back?’ Harriet asked.

‘It’ll be nice to see my friends again,’ said the hare.

‘Have you got lots?’

‘We’re all friends on Pars. There’s no such word as “enemy” in the language.’

‘I’m your friend, aren’t I, Wiz?’

‘Certainly,’ said the hare, and Breeze whinnied loudly.

‘What’s she saying?’ asked Harriet.

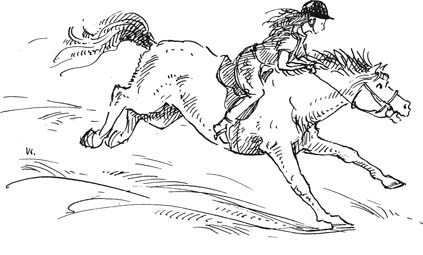

‘She’s saying, “Why are we standing here while you chatter away to that old hare, when we could be having a good gallop?” Come on – race you!’

‘You always win,’ said Harriet. ‘You’re faster than Breeze.’

‘All right,’ said Wiz, ‘we’ll make it a handicap. Go on, off you go.’

Any minute now he’ll pass me, Harriet thought as she urged the pony on, but no hare appeared beside her. When at last she drew rein, she looked round but there was no sign of Wiz. She rode back, puzzled, and after a while she came upon a hedgehog waddling along.

‘Whatever are you doing up here on the downs?’ she said, and the hedgehog gave a kind of grunt.

Harriet rode a little further, looking for Wiz, but then she heard a voice behind her.

‘You won,’ said the voice and, wheeling the pony round, Harriet saw not a hedgehog but a hare.

‘It was you!’ she said, laughing. ‘A sparrow, a goldfinch, a snail and now a hedgehog. Whatever will you turn into next, I wonder?’

‘A Partian, next full moon,’ said the hare.

‘I shall miss you,’ said Harriet. ‘I told Dad I wasn’t lonely here on the farm, but I shall be when you’ve gone and it’s just the two of us again.’

‘Oont,’ said the hare.

‘Why, what have I said wrong?’

‘You’ll see, before long, sure as eggs is eggs.’

‘That’s what I got that money for,’ said Harriet. ‘I sold some eggs to a lady who came to the farm. Dad says we can get some more hens, and then I can sell lots.’

‘Perhaps she’ll come back for more, this lady,’ said Wiz.

‘She might.’

‘She will.’

‘How do you know?’

‘Hares are witches, aren’t they?’

By the time the newcomer to the village came again to Longhanger Farm, Mrs Wisker had found out a lot more about her.

‘She’s a book-writer,’ she told Harriet. ‘Writes little books for kiddies, they say, though she’s got no children of her own. Mrs Lambert, she’s called, but there ain’t no sign of Mr Lambert yet. I expect she’s gettin’ the old place straight first. Any road, she seems to like your eggs, my duck. Goin’ to come regular, she said, didn’t she?’

‘Yes,’ said Harriet. ‘She’s my first customer.’

The next time that Mrs Lambert came to the farm to buy eggs was not on one of Mrs Wisker’s days.

‘All alone, Harriet?’ she said when the door was opened.

‘Yes. Dad’s ploughing the Ten Acre.’

‘I think I must have seen him as I came along the lane. I saw a green tractor. Can I have some more of your big brown eggs, please, Harriet? By the way, I should have said – my name is Lambert, Jessica Lambert.’

‘You write stories for children, don’t you?’ asked Harriet as she filled a tray with eggs.

‘Yes, for very young children.’

‘What about?’

‘Animals, mostly. Possibly your mother read you one or two of my books when you were little?’

‘I wouldn’t know,’ Harriet said. ‘She died when I was very small.’

‘Oh. Sorry. I didn’t know.’

‘That’s all right,’ said Harriet.

Little did she think, as she watched her customer drive away, that she would see her again so soon. For not ten minutes later the door-bell rang again, and there on the step stood Mrs Lambert, a bloodstained handkerchief held to her nose.

‘Whatever’s happened?’ cried Harriet.

‘I’ve had a bit of an accident,’ Mrs Lambert said. ‘I had to swerve suddenly in the lane, and the car went into the ditch and I banged my face. It’s nothing much, just a nosebleed I think, that’s all, but the car’s stuck and I wondered – d’you think your father would come and pull me out with his tractor?’

‘Yes,’ said Harriet, ‘of course he would. I’ll go and fetch him. D’you want to wash your face? Would you like a clean hanky?’

‘Yes please, Harriet,’ said Mrs Lambert. ‘Then I’ll go back down to the car and wait for help.’

A little later, Harriet’s father got down from the cab of the big green tractor and held out a hand.

‘John Butler,’ he said. ‘How do you do?’

‘Not very well, I’m afraid,’ said Mrs Lambert.

‘You haven’t broken your nose?’

‘No, I don’t think so. And I hope there’s nothing broken in the car. It’s just that I can’t get out of the ditch because the nearside wheels are spinning.’

‘We’ll soon have you out of there,’ said Harriet’s father, busy with a rope, and sure enough the big tractor pulled the little car out as easy as winking.

‘All’s well that ends well,’ said Harriet’s father as he unhitched the tow rope.

‘Not quite,’ said Harriet. ‘There is something broken – in the back of the car.’

‘What?’ said Mrs Lambert.

‘Every single egg you just bought,’ said Harriet.

Mrs Lambert smiled ruefully.

‘All the fault of that silly animal,’ she said. ‘I had to swerve to avoid running over it. It suddenly came out of the hedge and calmly sat up in the middle of the lane as though all it wanted was for me to go in the ditch.’

‘This animal,’ said Harriet’s father. ‘What was it?’

‘A hare.’