Chapter Nine

It was the final weekend of Harriet’s summer holidays.

‘And of Wiz’s too,’ she said to Breeze as she was mucking out the loose-box, watched by Bran.

The pony blew through her nostrils and the dog whined softly, as though they knew how Harriet was feeling.

‘Life’s never going to be quite the same again without my hare,’ she said. ‘No more magic, no more surprises. He promised to do me a good turn one of these days. I suppose that must have been the trip to London with Jessica. And talk about trips – just think how far he’ll be going on Wednesday night when the moon is full. When I was in the Planetarium, I looked to see which was the furthest away and it was Pluto, but Pars is probably ten times further. I suppose he’ll change into a Partian before he gets into the spacecraft. I wonder where it will land?’

Later, she walked down the trackway and across the first field to the one beyond where, a mere five weeks ago, she had seen that corn circle in the wheat.

Now it had been ploughed and worked down and sown with a grass-seed mixture, and already there was a faint tinge of green against the brown earth.

There was something else brown there too, she could see, just where the corn circle had been, and because it sank as she walked towards it, she knew it was a hare and not just a lump of muck.

Not until Harriet was almost upon it did the hare spring up and run away, and she bent down and put her hand in the slight hollow of its form, and felt the warmth of it.

‘Well, you weren’t Wiz,’ she said, and a voice behind her said, ‘Too true.’

‘Oh,’ said Harriet to her hare, ‘was that a friend of yours?’

‘You could say that,’ replied Wiz.

‘I’m afraid I frightened him.’

‘Oont,’ said the hare, the only word of the Leporine language that Harriet had ever heard. It meant disapproval, she knew.

‘What have I said wrong?’ she asked.

‘You didn’t frighten him, you frightened her,’ said Wiz. ‘I’ve tried to tell her that you wouldn’t hurt her, but she has no confidence in humans. Let’s hope her children may grow to be more trusting.’

‘Children? She has babies?’

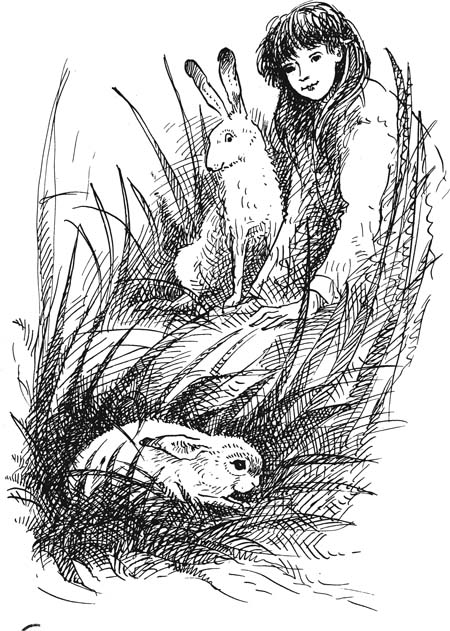

‘Her three leverets are in this field. Unlike their mother, they will not move when you approach, for she has told them to keep perfectly still. Each one has been left in a different part of the field and, when you have gone, she will go to each in turn to feed it.’

‘Why aren’t they all in a nest together,’ asked Harriet, ‘like baby rabbits would be?’

‘Baby rabbits,’ said Wiz, ‘can afford to be born blind and naked and helpless, because they’re safe underground. But hares live above ground, so the leverets stand a better chance of survival if they’re separated. Come, I will show you.’

So Harriet followed as Wiz led her in turn to each of the three recently born babies. Like all leverets, they had come into the world with a covering of hair, open-eyed and able to run, but they all lay still as stone as Harriet bent and gently stroked them.

‘Three little does,’ said Wiz.

‘They’re lovely!’ said Harriet.

‘Aren’t you going to congratulate me then?’

‘You mean . . .? Oh Wiz! How wonderful! To think that when you’ve gone, your daughters will still be here! Will they be magic?’

‘They won’t talk to you, or change into other creatures, if that’s what you mean. But I like to think that maybe they’ll be a little different from the average hare.’

‘How shall I know them from other hares, once they’re grown?’

‘Because, unlike other hares, they will never run away from you. I am going to teach them that right away, now that they’ve seen you. They will run from any other human being, or from any enemy like a dog or fox. But if, in time to come, you chance upon a hare that remains lying in its form and allows you to stroke it, that will be one of my daughters.’

‘That will be brilliant!’ said Harriet. They’ll always remind me of you, Wiz, she thought as she walked home. Not that I could ever forget you.

Jessica Lambert came that afternoon for eggs, and Harriet said to her suddenly, ‘Do you believe in magic?’

‘Of course I do,’ said Jessica. ‘Anyone with any sense does.’

You sound just like Mrs Wisker, Harriet thought.

‘Can animals be magical?’ she said.

‘Some can,’ said Jessica. ‘Hares have always been thought to be beasts of magic.’

That’s exactly what Wiz said, thought Harriet.

‘Dad shot one when he was combining,’ she said.

Jessica sighed.

‘Oh dear,’ she said. ‘I wish he wouldn’t shoot them, really.’

And now, thought Harriet, you sound like me.

‘Couldn’t you ask him not to?’ she said.

‘Why don’t you?’

‘He’d take more notice of you.’

‘Why don’t we both ask him?’

So they did.

‘What’s all this?’ John Butler said. ‘An anti-bloodsports deputation?’

‘No,’ said Jessica. ‘We’re not trying to stop you potting the rabbits and pigeons that damage your crops. We’re just asking you not to shoot hares again.’

‘Ever,’ said Harriet.

‘Why not?’

‘Because,’ said Jessica, ‘we both happen to be rather fond of hares.’

‘I’m fond of hare too!’

‘To eat, he means!’ cried Harriet, close to tears. ‘Please, Dad, say you won’t!’

‘All right, all right,’ said her father. ‘I hereby solemnly promise that I will never again shoot a hare on Longhanger Farm. Will that do?’

‘Yes,’ they said. ‘That will do.’

‘And come and have Sunday lunch with me, both of you,’ said Jessica. ‘I’ll do you roast beef and all the trimmings.’

‘It seems funny,’ said Harriet to her father when her first customer had driven away, ‘to be still making Jessica pay for her eggs. I mean, you ought to give your friends things, not make them pay.’

‘Maybe she won’t be buying them for much longer,’ Harriet’s father said.

‘Why not?’

‘Oh . . . I don’t know . . . she might be moving house.’

‘Oh, I hope not!’ said Harriet.

And I hope so, said her father, but he said it to himself.