Chapter Eleven

Harriet dressed and went to let out her hens and to feed the calves. As usual, she looked in through the door of the milking-parlour and called, ‘Morning, Daddy.’

‘Hares!’ said her father. ‘You’re meant to say, Hares!’

‘I already have.’

‘Oh, that’s all right then.’

No, it’s not all right, said Harriet to herself. It’s supposed to bring good luck but how could it when Wiz was going? Would she even set eyes on him again before he went?

All morning she wandered about the farm hoping to see her hare, but there was no sign of him. And when in the afternoon she rode over the downs, calling his name, there was no answer except the bleating of sheep, the sad cries of lapwings, and the sigh of the wind.

But when, in the evening, Harriet went out into the kitchen garden to pick the last of the scarlet runners, she found that someone else had got there first.

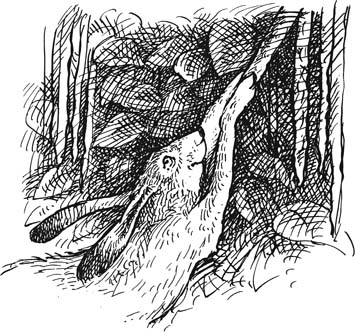

‘Hope you don’t mind,’ said the hare, standing on his hind legs to pull down a bean pod, ‘but I couldn’t resist a last snack.’

‘Don’t you have vegetables on Pars?’ Harriet asked.

‘Heavens, no! We live on synthetic, additive-free, low-cholesterol pills,’ said Wiz. ‘I shall miss being a hare.’

‘I shall miss you,’ said Harriet, ‘dreadfully.’

Wiz bit through the bean pod with his two large front teeth and began to chew, moving his lower jaw from side to side.

‘Very suitable for hares, these beans,’ he said.

‘Why?’

‘They’re both runners.’

Harriet stood watching, without saying anything.

‘It was supposed to be a joke,’ said Wiz.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Harriet. ‘I don’t feel like laughing.’

‘Oont,’ said the hare. He swallowed his mouthful and looked directly up at her. ‘Listen to me, Harriet,’ he said. ‘You mustn’t feel sad. Look at it from my point of view. I’m an alien on a strange planet, and though I’ve had a lovely time, I’m looking forward to going home, to Pars, to my friends. Of course I shall miss you, but I’m happy to be going and you must be happy for me. By this time tomorrow you will be a very happy girl indeed, let me tell you. You told me that you believed every word I said. Believe me now.’

‘All right,’ said Harriet. She bent and stroked his tawny back.

‘Stroke my children when you come upon them,’ said the hare, ‘and think of me.’

‘I will, Wiz,’ said Harriet. ‘But I don’t want to say goodbye.’

‘Then don’t,’ said the hare, and with one easy bound he leaped over the garden wall and was gone.

At the end of that first day of September, Harriet stood at her bedroom window, looking down into the valley below and hoping perhaps for one last glimpse of her hare, but there was no sign of him.

Already the full moon was sailing in the darkening sky, and Harriet stared up at it, thinking as she would now always think that that business of the Man in the Moon was rubbish. What was on the great round disc was, without a doubt, the outline of a hare.

Her father came in to say good-night.

‘You haven’t sold out of eggs, have you, Hat?’ he asked.

‘No. Why?’

‘Might need an extra one for breakfast tomorrow.’

Greedy old Dad, Harriet thought, he never usually has two.

The night was a still one, and for some long time Harriet lay awake, straining her ears for any unusual sound. When she did at last fall asleep, she slept lightly, so that a distant noise woke her.

It was a rushing, tearing, swishing noise – just like the sound a rocket makes on Guy Fawkes Night, but this time it did not come from the valley below but from the opposite direction, far away, right up at the top of Longhanger Farm, up on the downs.

Harriet looked at her watch. It was midnight, the witching hour.

‘Be happy for me,’ he had said, she thought, so I must be, and she lay down again and shut her eyes.

When she opened them again it was to find that she had slept late. She went to the window and saw that her father had finished the morning milking, that the herd was already out at pasture, and that a car was coming up the trackway.

Jessica’s car, thought Harriet. She must be out of eggs. And Harriet dressed quickly and ran downstairs.

Her father was already in the kitchen.

‘Lay an extra place, will you, Hattie, please?’ he called. ‘Jessica’s coming to breakfast,’ and with that there was a knock on the front door.

‘How d’you like your boiled egg, Jessica?’ Harriet’s father shouted from the kitchen.

‘Sort of middling, please, John. Softish yolk, firmish white, if you know what I mean.’

‘I do.’

‘That’s how we like ours,’ said Harriet.

What’s Jessica doing here for breakfast? she thought. I mean, I’m glad she’s here, I like her. Come to think of it I like her very much indeed. But why breakfast?

Not until they had finished eating did Jessica say, ‘You’re wondering why I’m here so early in the day, aren’t you, Harriet? It’s because I’ve got some news to tell you and I couldn’t wait any longer.’

‘Oh no!’ cried Harriet. ‘You’re moving! Dad said you might be moving house.’

‘Yes, I am. Not for some while yet, but then I shall sell the old turnpike cottage.’

‘Where are you going to live then?’ asked Harriet.

‘At Longhanger Farm,’ said her father.

Harriet looked blank. Her mind was still full of thoughts of Wiz, speeding away on his long long journey to Pars, and she could not grasp what was being said.

‘Last Sunday,’ said Jessica, ‘after lunch when your father asked you to go and have a look at Buttercup, it was because he wanted to ask me something.’

‘Over the washing-up,’ said John Butler. ‘Dead romantic.’

‘He asked me to marry him, Harriet,’ said Jessica Lambert, ‘and I said, “Yes, but only if Harriet approves.”’

Suddenly everything was blindingly clear to Harriet.

It was all Wiz’s doing!

This was the good turn he’d promised. This was the really big surprise. He had arranged the whole thing, from the moment when he’d sat in the lane and caused Jessica to go in the ditch, so that Dad could rescue her.

‘Tomorrow you will be a very happy girl indeed,’ he had said yesterday. In fact, Harriet was so delighted that at first she could not speak. She jumped up from the table and dashed round to Jessica and gave her an enormous hug, and then she gave her father another one.

At last she said, ‘It’s like a fairy-tale.’

Jessica laughed.

‘There’s often a wicked stepmother in a fairy-tale,’ she said, ‘but I’ll try very hard to be a good one. And I’ll start by letting you off the washing-up, Harriet. Or can I call you Hattie too, now?’

‘Whatever you like,’ said Harriet happily.

And she sat on by herself at the breakfast table after they had cleared it, and listened to the sounds of talk and laughter coming from the kitchen, and thought how brilliant it was going to be for both of them. For Jessica, after that awful first husband who called her ‘Jess’ like a sheepdog and knocked her about, and for Dad, after almost six long, lonely years.

She stared up at the portrait hanging on the wall.

To Jessica, to her father, to Mrs Wisker or anyone else, it was just a very good likeness of a hare.

But to her and her alone, it was a portrait of a wizard – of a beast of magic who, for a thousand full moons to come, would remain, as he had always been, Harriet’s hare.

THE END