CHAPTER 1

Can One Person Make a Difference?

Nobody made a greater mistake than he who

did nothing because he could do only a little.

—Edmund Burke

This book is about the steps you can take and the choices you can make to combat global warming.

Global warming presents one of the most enormous challenges humanity has ever faced. It threatens to affect nearly every aspect of our lives—our health, the availability of freshwater, the future of many coastal communities, our food supply, and even government stability as nations around the world begin to confront the adverse consequences of climate change.

More than a century ago, a Swedish scientist named Svante Arrhenius recognized that burning fossil fuels would create a thickening layer of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, thus trapping a growing proportion of the sun's heat and causing Earth to warm up.

There's been a lot of misinformation about climate change in recent years. But political spin doesn't change the facts. Since Arrhenius's time, tens of thousands of scientists have studied and measured the climate in great detail and from many vantage points. And the more they learn, the more certain they are that the planet is warming at an alarming rate, that the warming is caused by human activity, and that if this warming is left unchecked, we are on a dangerous and unsustainable path toward disruptions in Earth's climate.

The overwhelming majority of the world's experts on every aspect of climate science have concluded that we need to make swift and deep reductions in our emissions of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping gases to avoid the worst consequences of global warming.

We will review some of the most important scientific details in chapter 3, but this book is not primarily about the science and consequences of global warming. It's about how you can help solve the problem by making thoughtful, effective decisions in your daily life. The fact is, global warming is a human-caused problem, and it is within our power to solve. Individual actions can and do make a difference.

Maybe you're already committed to doing everything you can to reduce your contribution to global warming. If so, that's great. Our team of experts has compiled the information in this book to help you determine which actions you can take to be most effective.

It may be, however, that you haven't taken steps to combat global warming. After all, climate change is occurring on an almost unimaginably vast scale, and you are just one of the world's nearly 7 billion inhabitants. It is natural to feel dwarfed by the numbers. This book will help you see that while the world's reliance on fossil fuels is the basis of our problem, the choices each of us makes every day have enormous consequences. Our goal in these pages is to show you how changes you can make right now—multiplied many, many times over—can make a real difference in helping forestall the worst consequences of global warming.

To appreciate this point, consider the “penny parable,” based on the real-life experience of someone named Nora Gross. Today, Gross is a graduate student at New York University. But 20 years ago, as a young girl growing up in Manhattan, she told her father she wanted to give her penny collection to the homeless man they often passed on the street near their home. In her childlike way, young Nora reasoned that if everyone did what she was proposing to do, perhaps no one would be homeless. Her father might have told her that her pennies couldn't possibly make a dent in the widespread scourge of homelessness. But instead, touched by his daughter's compassion for a stranger, Nora's father encouraged her to follow through on her idea. The two of them soon founded an organization, called Common Cents, dedicated to harvesting spare pennies.

In the ensuing years, Nora Gross's idea has mushroomed beyond all expectation. Since its founding, Common Cents has, amazingly, encouraged more than a million children around the country to collect almost 1 billion pennies. That adds up to $10 million, enough money to alleviate the suffering of thousands of homeless people—people who would not have been helped if one young girl had thought she couldn't make a difference.

Fanciful though the example may be, Nora Gross's story offers an important lesson that is relevant to the problem of global warming. It demonstrates how small individual actions can reap huge dividends in the aggregate, even when the individual actions seem simple. Many of the changes you can make to combat global warming are as easy and painless as giving spare pennies to a good cause, and the cumulative effects can be dramatic. For example, the U.S. government's Energy Star program estimates that if we improved the energy efficiency of residential buildings in this country by just 10 percent (a goal easily met by existing technology), Americans would save about $20 billion and reduce global warming emissions by as much as if 25 million cars were taken off the road. Small individual improvements in energy efficiency, in other words, can make a very big difference.

Of course, you may feel that your hands are simply too full with work or raising your kids to get into the “saving the planet” business. If you are curious enough to look through this book, though, you will still find valuable information. Many of the choices offered in the following chapters won't just lower your emissions of carbon dioxide; they can also improve the quality of your life, save you money and time, and even improve your health.

That's what the people of Salina, Kansas, found when they entered a yearlong competition with neighboring cities in their state to see who could save the most on their energy bills. Many residents of Salina have doubts about the findings of climate science. Nonetheless, these Kansans say they don't like their nation's dependence on foreign oil; plus, like most Americans, they are thrifty and very much like saving money. During this contest, the entire city of Salina (population 46,000) was able to reduce its overall carbon dioxide emissions by 5 percent. Jerry Clasen, a local grain farmer, captured the prevailing sentiment, commenting, “Whether or not the earth is getting warmer, it feels good to be part of something that works for Kansas and for the nation.”

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

According to the U.S. government's Energy Star program, if Americans improved the energy efficiency of their homes by just 10 percent, they could cut some $20 billion from their utility bills and remove emissions equivalent to taking some 25 million cars off the road.

As the folks in Salina discovered, the inefficient use of energy in the United States makes it easy for anyone seeking to reduce emissions to reap quick rewards. Did you know, for instance, that fossil fuel power plants typically release roughly two-thirds of their energy as waste heat? Or that less than 20 percent of the gasoline a car burns goes toward propelling it down the road? Even without changing to renewable power sources that can generate electricity with zero carbon emissions, we can dramatically increase the efficiency of our use of fossil fuels with cost-effective, off-the-shelf technology. By one estimate, technologies to recover energy from waste heat and other waste resources in the United States potentially could harness almost 100,000 megawatts of electricity—enough to provide about 18 percent of the nation's electricity.

But we don't have to wait for more efficiency to be built into the system. The chapters that follow show clearly that as end users of this energy, we have at our disposal a wide variety of simple techniques to squeeze much more out of our current energy use, saving money and reducing our emissions.

What this means for you is that you can probably make some simple changes that will yield real improvements in your energy efficiency. Not long ago, a Canadian utility company drove home this point in a much-lauded television commercial that urged its customers to conserve energy. The ad depicts individuals engaging in laughably wasteful behavior. One guy is wrapping his sandwich in aluminum foil, but instead of using one sheet, he keeps wrapping and wrapping until he has used the entire roll. A woman takes just one bite of an apple, then drops it on the ground and picks up a new one, repeating this mindless act until the camera zooms out to reveal the ground below her strewn with bitten apples. The spot ends with a family going out of their house without turning out any of its brightly burning lights. It leaves the viewer to ponder why this behavior isn't every bit as preposterous as the others.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

Our energy systems are remarkably inefficient. On average, only about 15 to 20 percent of a gallon of gasoline goes toward propelling a car or truck down the road. And an average fossil fuel power plant turns only about one-third of the energy it uses into electricity.

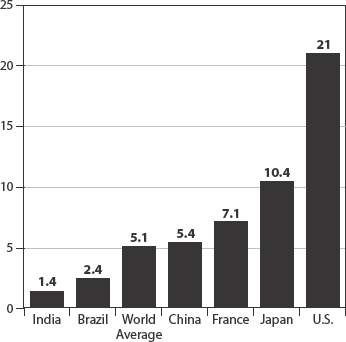

In many ways, the issue really is that simple. If you live in the United States, on average your activities emit a whopping 21 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere annually.* That's one of the highest per-person emission rates in the world and some four times higher than the global average.

There's no getting around the situation depicted in the graph on page 8. Compared with our counterparts around the world, we are responsible for outsized emissions and outsized costs. The emission levels of the average American are roughly four times the global average, as noted above, and they are also roughly 15 times those of the average citizen of India. To be sure, poverty in many parts of India, as in many countries, keeps personal consumption—and associated emissions—far below the level currently found in the United States. But on a per capita basis, even most industrialized European countries—with standards of living similar to those in the United States—emit less than half the carbon dioxide the United States does.

When you do the math, it reveals that, on average as an American, your activities emit just over 115 pounds of carbon dioxide daily. Think about that for a moment: your actions are responsible for sending a fair portion of your total body weight up smokestacks and out tailpipes every day. And the heat-trapping carbon dioxide each of us is contributing is accumulating in the atmosphere to cause global warming.

Figure 1.1. Global Carbon Dioxide Emissions (Tons per Person Annually)

The United States’ per-person carbon dioxide emission levels are about four times the world average.

Source: UCS Modeling and World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2007.

Can we reduce our global warming emissions? Of course we can.

Bear in mind, for instance, that just two decades ago the chemicals in many common products, from refrigerators to hair spray, were eating away at the protective ozone layer in the atmosphere. The resulting ozone hole seemed to present an insurmountable global problem. Scientists and citizens alike were anticipating a future of unfettered ultraviolet radiation wreaking havoc on our skin and health. But with effective planning and innovation, we tackled the problem. Citizens, scientists, and government officials came together to phase out the harmful substances responsible for the problem. Today the stratospheric ozone layer is on a path to recovery.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

On average, Americans each cause more than 20 tons of carbon dioxide to be emitted into the atmosphere annually. That's more than four times the global perperson average and more than twice the amount emitted per person in most industrialized western European countries with high standards of living.

An equally dramatic example is the story of the Cuyahoga River in Ohio. Today the Cuyahoga supports a wide variety of recreational opportunities, from kayaking to fishing, and boasts some 44 species of fish. Just a few decades ago, however, the Cuyahoga was one of the most polluted rivers in the United States. In the portion of the river from Akron to Cleveland, virtually all the fish had died. The situation seemed hopeless. But finally, when debris and chemicals in the Cuyahoga infamously caught fire in 1969, people were galvanized into action. Some have even called the public reaction to the Cuyahoga River fire the start of environmentalism, for that catastrophe helped spur a legislative response that included the Clean Water Act, the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, and the creation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The point is that difficult problems aren't always as intractable as they seem. That doesn't mean they are easy to solve, of course, as any of the concerned citizens, activists, and government officials who fought to clean up the Cuyahoga River could attest. The problem seemed dire, and solutions were often elusive. In fact, the Cuyahoga actually caught fire more than a dozen times, the first time in 1868. It took until 1969—more than 100 years—to spur the necessary actions.

Let's be clear: global warming is much greater in scope than a burning river and more complex than a hole in the ozone layer. But as we said at the beginning of this chapter, people caused the problem, and people can solve it. We already have many of the tools and technologies we need to address global warming. The key is for each of us to begin to work toward solutions.

We all have examples of the power of individual actions. But the experience of a builder in Montana named Steve Loken is particularly worth recounting. One day some years ago, Loken visited a spot north of his home in Missoula where the forest had been clear-cut. The visit changed his life. At that moment, he says, he recognized the extent to which his work as a builder wasted precious resources. Loken didn't like the idea of contributing directly to the decimation of old-growth forests. “I realized I was part of the problem every time I blindly followed building practices that were inherently wasteful,” he says.

Instead of continuing with business as usual, Loken decided to be part of the solution. He looked for ways to build that would be sustainable to the environment and the planet's climate. He began with an experiment: spending his savings to build a home for his family using exclusively recycled or salvaged materials. The result was extraordinary. The house Loken built looked and felt in every way like a handsome new suburban home. Visitors would never know that most of the wood in the house was a composite material made from the sawdust and shavings left over from the milling of lumber. They couldn't tell that the home's insulation was derived from recycled newspapers, that its ceramic floor tiles were manufactured from recycled car windshields, or that its carpets had once been plastic milk cartons.

At that time, it was not at all easy to find these new, unconventional materials and learn to use them, but Steve Loken demonstrated that houses could be built sustainably without sacrificing quality. And now, after years of researching new building technologies in the face of much skepticism from other builders, an amazing thing has happened: Steve Loken's house has helped spur dramatic changes in building techniques around the world. Much to his astonishment, many thousands of people, including leading architects and builders, have made the pilgrimage to Missoula to see his home. He founded an organization, the Center for Resourceful Building Technology, to help others find more environmentally sustainable ways to build. But his techniques caught on so quickly and were replicated so widely that he soon decided the organization wasn't needed anymore. Meanwhile, Loken's contracting business—focusing on recycled materials and energy-efficient design—is booming as never before, with offers to build projects all around the country.

When you think about it, this story says a lot about how change occurs. Steve Loken is not that different from the rest of us. All he did was resolve to make some changes and then educate himself about how to do things in smarter ways. The changes reduced his family's environmental impacts, made him feel better about his work, inspired others, and helped his business prosper. When it comes to reducing your global warming emissions, you can very likely achieve similarly good results through your own efforts. And we've written this book so you don't have to do the research on your own, the way Steve did.

If there is any lesson that our fast-paced technological world reinforces over and over again, it is that change often happens more quickly and dramatically than we anticipate. Just over a century ago, only 8 percent of U.S. homes even had electricity, and Henry Ford had produced only a few thousand vehicles in his recently built car factory. Who could have imagined that by the mid-twentieth century, virtually every American home—and millions of others around the world—would have electricity or that the automobile would redefine American lifestyles and fundamentally transform the economy?

For an equally powerful example right at your fingertips, consider the cell phone. If it's a current model, it probably has a storage capacity of up to 32 gigabytes of information. That's more than 10 million times the onboard computer storage capacity of the Apollo 11 spacecraft when it traveled to the moon in 1969.

Who could ever have imagined then that such a dramatic increase in computing power would become so widely available the world over in a handheld wireless device?

The point is that it's hard to envision how dramatically—or how quickly—things could change as we wean ourselves off fossil fuels and move into an economy based on efficiency and renewable energy. One survey of nearly 50 past forecasts of future energy use in Europe and worldwide found that nearly all of the forecasts had underestimated the actual increase in renewable energy generation. In one example, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projected in its 2002 World Energy Outlook that global wind energy capacity would reach 100,000 megawatts by 2020. In reality, the wind industry passed this mark in early 2008 and is now close to achieving double the predicted capacity a decade ahead of the IEA's prediction. When it comes to wind energy, China alone shows how much can be done. In just four years, from 2005 to 2009, that nation achieved an astonishing 20-fold increase in installed wind capacity. The rapid pace of growth shows what's possible in the global shift to a cleaner energy supply.

UCS Climate Team FAST FACT

Global wind energy capacity has increased at almost twice the rate estimated by the International Energy Agency, reaching nearly 160,000 megawatts in 2009. China alone achieved a 20-fold increase in installed wind capacity between 2005 and 2009.

You and your family aren't likely to be building new wind turbines to generate electricity. And you probably aren't in the contracting business like Steve Loken. Nevertheless, you can still go a long way toward weaning your household off fossil fuels and slashing your family's carbon emissions simply by making better choices about what you buy and how you live. The chapters ahead will show you how.

* A note about numbers and terms: Throughout this book, all discussions of emissions, unless otherwise noted, use pounds and tons (2,000 pounds in a ton)—the most familiar units of measurement to most U.S. readers. Similarly, discussions of “carbon emissions” refer to emissions of units of “carbon dioxide equivalent” (CO2e), as will be more fully explained in chapter 7.