MIRACLE IN THE CHANNEL

Remember 2009’s “Miracle on the Hudson,” when a commercial airliner had to make an emergency landing in New York’s Hudson River? The passengers and crew of the plane were saved thanks to the fact that everyone remained calm and they had a smart, savvy captain. Here’s the story of a similar plane crash that happened in the English Channel, way back in the 1920s, at the dawn of commercial aviation.

UP, UP, AND AWAY

One afternoon in October 1926, ten passengers—six male and four female—boarded an airplane in Croydon, South London, on a flight bound for Paris. At the time, the airline industry was still in its infancy, and the airline, Imperial Airways, was not quite two years old. In that short span of time, Imperial had flown 25,000 passengers more than two million miles all over the far-flung British Empire, with only one fatal plane crash—an impressive safety record in those early days of commercial aviation.

The plane on this flight was a twin-engine Handley Page Type W, which though a fairly sturdy and reliable aircraft in its day, would be considered a shockingly primitive aircraft by today’s standards. For one thing, it was a biplane made not of aluminum but of wood, canvas, and wire. And though the ten passengers sat in a tiny enclosed cabin, the pilot, Fredrick Dismore, and his mechanic, Charles Pearson, sat in an open cockpit, exposed to the elements. (One modern touch: the Handley Page was the first airliner designed with an onboard lavatory.)

THAT SINKING FEELING

The flight began normally enough, but about an hour and fifteen minutes into the flight, the plane lost power in the starboard (right) engine as it was crossing over the English Channel. Perhaps because the plane was fully loaded with fuel, passengers, luggage, and sacks of mail, the plane’s remaining working engine wasn’t powerful enough to keep the plane in the air. It began losing altitude. Unable to restart the engine, Captain Dismore realized he was going to have to ditch the aircraft in the English Channel. “And to make matters worse,” he later recalled, “there was not a boat in sight.”

Dismore began making distress calls on the radio and kept at it for as long as the plane remained airborne. “I knew that once the airplane touched the water the wireless [radio] would be put out of action,” he said. While he sent out one mayday call after another, mechanic Charles Pearson went back into the passenger cabin and started passing out life preservers to the passengers. “There was no panic of any kind, but we all realized we were in great peril,” a passenger named Bertram Cook said later.

...so she wouldn’t sit on the Iron Throne when visiting the Game of Thrones set.

The plane remained airborne for another four minutes before splashing down about nine miles off the coast of France. “The sea came nearer and nearer. The airplane was going at about forty miles an hour, and I knew that everything depended on landing in such a way that the machine would not be overturned. It was touch and go, but the sea was calm, and I was just able to land absolutely flat,” Captain Dismore told the Daily Express newspaper.

Thanks to a combination of luck and Dismore’s skill, the plane did not break apart when it hit the water, nor did it roll or flip over. It was intact, upright, and afloat… for now. Perhaps one benefit of being made largely of wood and canvas was that it floated better than it might have if it had been made of metal. Captain Dismore estimated it might remain afloat for as long as an hour, but no longer.

LET ’ER RIP

Bertram Cook was seated in the rear of the cabin, and after the plane hit the water he saw a notice on the ceiling that read “In Case of Emergency, Pull the Ring.” He pulled the ring, and “the canvas of the roof came apart,” he later recalled, creating an opening and giving him a means of exiting the cabin. He clambered out of the airplane, then helped two female passengers climb out onto the tail of the aircraft after him. As he did, he saw passengers in the front of the cabin climbing out of a window onto the wings.

Once everyone was safely out of the aircraft, there was nothing to do but wait… and hope to be rescued before the plane sank. Amazingly, considering the plight they were in, the passengers did not panic, as passenger Virginia Bonney, 21, later recounted in a letter home to her fiancé, Joe Jeffrey. “Joe, you never saw such a calm lot of people. No one screamed or even talked loud—maybe I did. I don’t know. I was so dazed I really thought I was dreaming.”

The engines were the heaviest part of the aircraft, and as the plane took on water it began sinking by the nose. As it did, Captain Dismore ordered the people sitting on the wings to move back toward the tail in an attempt to keep the plane level for as long as possible. “The men formed a sort of chain and hauled as many of the women as they could to the best position on top of the tail,” he told the Daily Express.

DEFLATED

By now the passengers had their life vests on, but they were an inflatable type—and in this era, long before mandatory preflight safety demonstrations, no one had told the passengers how to inflate their vests. “The worst thing in the affair was the life belts. No one knew how to use them,” Bonney wrote to her fiancé. “They were no more use than a canvas jacket. Here we were all hanging on the tail of a sinking airplane—all of us in heavy coats, and no air in our life preservers. It was about fifteen minutes before we could get anyone to tell us how to blow them up.”

The oldest surviving ice cream recipe dates to 1665. The ice cream was flavored with mace and orange flower water.

Fortunately, those 15 minutes were about all it took for a fishing boat named the Invicta to steam to the rescue. Dismore was wrong when he said that he thought there were no boats in the area: The Invicta and a few others were nearby, and they saw the plane crash into the sea several miles from where they were fishing. As soon as it did, the skipper of the Invicta, Tom Marshall, cut loose his fishing nets (losing the value of the nets and the catch) and steamed at full speed toward the downed plane. By the time he arrived those 15 minutes later, the plane had taken on so much water that some of the passengers were standing in it up to their waists. “In another five minutes,” he remembered, “I think we would have been too late.”

A second fishing boat, the Jessica, arrived soon afterward, and together the two crews loaded the plane’s survivors on board. The boats had been fishing a few miles off the French coast, but rather than drop the passengers off in a French port, they were kind enough to take them all the way back to Folkestone, a port town on the southern coast of England. “Those fishermen were splendid, Joe,” Bonney wrote to her fiancé. “They took their own clothes off their backs and wrapped us in them. They only make 2 pounds a week and they lost 400 pounds by cutting their nets to come to us.”

ROUGH SAILING

But for Bonney and other survivors who were prone to seasickness, the trip back to Folkestone was nearly as harrowing as the crash itself. “We were three hours on that boat, and sick!” Bonney told her fiancé. “I was so cold I had to go down in the cabin and be sick. I couldn’t stand it on deck. It was awfully funny: Five of us huddled in there, taking turns throwing up on the floor, sometimes several of us going at once.”

On the way to Folkestone, the Invicta met up with a British Admiralty tugboat that had a radio aboard; it sent word to shore that everyone aboard the flight had been saved. (This was the first news that Imperial Airways received since Captain Dismore’s distress calls ended abruptly when the plane hit the water, causing the airline’s managers to fear that the plane and everyone aboard had been lost.) By the time the boat arrived in port, quite a crowd had gathered at the pier to celebrate the survivors’ good fortune. Cozy hotel rooms awaited, complete with warm baths that were already being drawn. “Everyone was nice to us,” Bonney wrote to her fiancé. “Except the reporters who literally tried to bribe the chambermaid to let them in our room with her key so they could take pictures of us—this after they had been told we had no clothes—only borrowed nightgowns. When we got to London we were besieged by them—we felt so important!”

In the next 10 million years or so, Neptune’s moon Triton will get too close to the planet, split apart, and form a set of rings around Neptune.

Other boats that arrived at the site of the crash tried to keep the downed plane afloat long enough to tow it back to port, but their efforts were unsuccessful, and the plane sank to the bottom of the English Channel. (The boats did manage to retrieve two sacks of Royal Mail airmail before the plane sank: after the letters were dried out, the letters whose addresses were still legible after soaking in seawater were sent on to their destinations.) Because the plane was not recovered, the cause of the engine failure was never determined. Imperial Airways lost its plane, but its record of no fatalities and no injuries remained intact: Most of the survivors escaped with only cuts and bruises. The most serious injury was suffered by mechanic Charles Pearson, who inhaled some exhaust fumes after he grabbed onto the plane’s exhaust pipe and it broke off in his hand.

There was one casualty, however: a passenger’s Pomeranian dog, which was somehow lost at sea before the fishing boats arrived. “We did not see what happened,” one unnamed female passenger told the Daily Express. “The dog was quite safe one moment, and the next thing we noticed that it had vanished.”

AND THEY LIVED HAPPILY EVER AFTER

“I still can’t believe it was possible to be so lucky,” Bonney wrote. “None of us, down in our hearts, thought we had a chance till we saw those fishing boats coming toward us. Why there happened to be a boat in that very part of the Channel and why they happened to see us go down is so remarkable it’s hard to believe.”

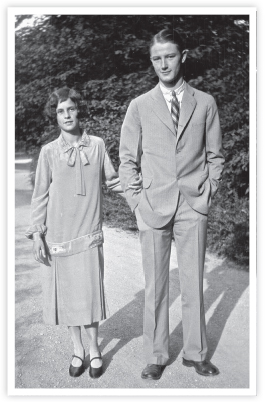

Virginia Bonney and Joe Jeffrey, 1926

(Virginia Bonney was reunited with Joe Jeffrey, and in June 1927 they were married. She lived to the age of 88 and passed away in 1993. The story, her letters, and the newspaper clippings describing the rescue come to Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader courtesy of her son, David L. K. Jeffrey. Thank you, David!)

The division symbol ÷ has a name—it’s called an obelus.