SIGNED, SEALED

& DELIVERED

July 4, 1776, is best known as the date the Declaration of Independence was adopted, but the founding fathers did something else that day: They appointed a committee to design a “Great Seal of the United States.” A simple job, maybe, but the project dragged on for years.

THE A TEAM

After the Second Constitutional Congress ratified the Declaration of Independence, they assigned a committee of three people with the task of coming up with “a seal for the United States of America”—a national emblem or coat of arms for the new country. In the 1700s, when countries signed treaties and other agreements, they did so by stamping the official documents with their state seals. Now that the United States had declared itself to be an independent nation, it was going to need a state seal too. And fast.

ROUND ONE

The three people chosen to design the new seal were three of the men most responsible for writing the Declaration of Independence: Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin. But they turned out to be better with words than they were with symbols and imagery. After considering numerous biblical and classical themes and failing to come up with something on their own, they enlisted the aid of a Swiss-born artist named Pierre Eugène du Simitière.

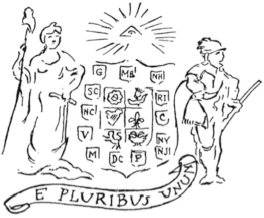

Du Simitière sketched a rough design (shown left) that featured two human figures: an allegorical female representing Liberty and a male representing an American soldier. These figures stood on either side of a large shield, the center of which featured symbols for six countries that large numbers of European Americans hailed from: England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Germany, and Holland. Surrounding the six national symbols were emblems displaying the initials of the 13 colonies, and floating above the shield was an “Eye of Providence in a radiant Triangle whose Glory extends over the Shield and beyond the Figures.”

Most human beings will see more of the surface of the Moon than they ever will of Earth.

A motto on a scroll at the bottom of the scene read: E Pluribus Unum (“From Many, One,” a reference to the 13 colonies that had joined together to form the Union).

ROUND TWO

Du Simitière’s design was submitted to the Continental Congress in August 1776. They were not impressed. Rather than approve it, Congress sat on it until 1780, when it handed off du Simitière’s design and other materials to a new committee and asked them to try again. This second committee passed the buck to Francis Hopkinson, the designer of the first American flag. Hopkinson developed du Simitière’s design further, adding 13 red and white diagonal stripes to the shield, and replacing the Eye of Providence with 13 six-pointed stars surrounded by clouds. He moved the male figure to the left and the female figure to the right, and put an olive branch in her left hand, symbolizing peace. Hopkinson also replaced E Pluribus Unum with Bello vel pace paratus, which means “prepared in war or peace,” and circled the design with the words “THE GREAT SEAL OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.”

ROUND THREE

The Continental Congress must not have liked that design either, because in 1782 it appointed a third committee to revise the work of the first two committees. The third committee relied on the artistic talents of a Philadelphia attorney named William Barton, who came up with his own version of the seal. His design kept the male and female figures with the shield between them, but this time the female (moved back to the left of the shield) represented the “Genius of America.” Her olive branch was replaced by a dove perched on her right hand. Barton also added a small white eagle atop the shield, holding a sword in its right talon and an American flag in its left, with an upper motto that read In Vindiciam Libertatis (“In Defense of Liberty”) and a lower one that read Virtus Sola Invicta (“Only Virtue Unconquered”).

91% of adults admit they pick their nose. (The other 9 percent are liars.)

Barton also proposed a design for the back of the seal that included an unfinished pyramid with 13 rows of stone, topped by the Eye of Providence that had been proposed by the first committee, and featuring the motto Deo Favente (“With God’s Favor”) and Perennis (“Everlasting”).

ROUND FOUR

The Continental Congress didn’t think much of Barton’s proposals either, so in June 1782 it took all the work that had been done by the three committees and dumped it in the lap of the Secretary of the Continental Congress, Charles Thomson. He didn’t have an artistic background, so rather than try and create something entirely new, he just picked the elements that he liked from each of the previous designs and used them to create his own design. He removed the male and female figures, reduced the size of the shield, and greatly enlarged Barton’s eagle so that it was big enough to support the shield on its breast. Over the eagle’s head was a constellation of six-pointed stars surrounded by clouds and rays of light. In its left talon the eagle clutched 13 arrows, symbolizing war; in its right talon it clutched an olive branch, symbolizing peace. In its beak it held a banner bearing the motto from the first design, E Pluribus Unum.

For the reverse side of the seal, Thomson stuck with the unfinished pyramid and the Eye of Providence, but changed Barton’s mottos to Annuit Coeptis (“He Has Favored Our Undertakings”) and Novus Ordo Seclorum (“New Order of the Ages”).

Thomson gave his ideas back to Barton for fine-tuning. Barton simplified the design and altered a few details, pointing the eagle’s wingtips upward and replacing the chevrons on Thomson’s shield with vertical stripes.

Then he presented the design to the Continental Congress on June 20, 1782. At last! The Congress finally had a design it liked, and it approved it that same day. The first seal was created later that same year. And though the unfinished pyramid design was approved for the reverse side, it was never actually made into a physical seal that could be applied to treaties. One of the very rare times it has ever been used for anything was in 1935, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered both the front and the back of the Great Seal to be placed on the back of the $1 bill. It has been there ever since.

Leeches were once used to treat nymphomania.

The Great Seal was first used on September 16, 1782, to sign a document authorizing General George Washington to negotiate an exchange of Revolutionary War prisoners with the British. It remained in regular use for another 59 years. By then it was pretty worn, and like an old coin, some of the details from the seal’s metal die, used to stamp or impress the image of the seal onto documents, had gotten kind of fuzzy. So in 1841 a new die was commissioned. It’s believed that the engraver of the new die simply copied the details from the old, worn die, rather than base his design on the 1782 legislation that established the details of the design of the seal, because that legislation specified that the eagle’s left talon should hold 13 arrows. In the new seal, the eagle holds only six. The new design also used five-pointed stars in the constellation over the eagle’s head. The old seal had six-pointed stars. Because of these discrepancies, the 1841 seal has become known as “the illegal seal,” even though the treaties and other documents that the seal was affixed to were just as legal as they would have been if the design had followed the letter of the law.

NIP AND TUCK

The next die, engraved in 1877, copied the design of the 1841 die. It wasn’t until 1881, when the 100th anniversary of the first seal was approaching, that the State Department decided to have the design of the seal updated to bring it back into compliance with the 1782 specifications. It took until 1884 for the U.S. Congress to appropriate $1,000 to pay for the work, after which the New York jeweler Tiffany & Co. was commissioned to update the design. Their head designer, James Horton Whitehouse, came up with the design for the 1885 seal.

Until he crashed his car in high school, George Lucas wanted to be a race-car driver.

If this seal looks familiar, that’s because very few changes have been made to the design since then. When the 1885 die was ready to be replaced in 1903, the commission went to a Philadelphia firm called Bailey Banks & Biddle, but rather than let the firm’s engraver, Max Zeitler, have a free hand with the look of the new die, he was instructed to produce a “facsimile” of the 1885 seal. So Zeitler produced what is essentially the same design, but brought out in finer, sharper detail (pictured).

The seal that’s in use today is still based on Zeitler’s 1903 design, and it’s unlikely to change anytime soon. In 1986 the Bureau of Engraving and Printing made a “master die” based on the 1903 design. In the future when the metal dies used to emboss treaties and other documents wear out, new dies will be made from this master die.

SOMETHING BORROWED, SOMETHING BLUE

What is believed to be the first official use of the Great Seal as a symbol of the presidency came in April 1877, when President Rutherford B. Hayes used an image of an eagle grasping at arrows and olive leaves on invitations to his first state dinner, given in honor of a visiting Russian grand duke. In 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt ordered that a version of the official seal be installed in the floor of the White House’s Entrance Hall; the designer of that image, a French-American sculptor named Philip Martiny, added the words

THE SEAL of the PRESIDENT of the UNITED STATES

around the edge of the circle. (Another change: the eagle’s head is turned to its left, facing the talon that held the arrows of war, instead of to the right, where the olive branch of peace was held.) That eagle remained in place on the floor of the Entrance Hall until Harry S. Truman became president in 1945. Truman didn’t like the idea of visitors to the White House walking all over the seal, so when he ordered his own extensive renovations to the White House in 1948, he had the seal removed from the floor and installed over the doorway of the Diplomatic Reception Room, where people could admire it but not step on it.

Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, Kent, Surrey, and Sussex are considered the “home counties” of England because they all surround London.

Truman was the first president to codify the design of the presidential seal, in his Executive Order 9646. Before the executive order, presidents used (or didn’t use) the official state seal as the presidential seal however they wished. In his executive order, Truman made a few changes to the presidential seal. He dictated that, as had always been the case with the Great Seal of the United States used by the State Department, the eagle on the presidential seal should have its head turned to its right, facing the olive branch of peace.

Truman also ordered that the presidential seal should be set on a dark blue background and be encircled by 48 stars, representing the 48 states in the Union. (He also considered adding a bolt of lightning issuing from the arrowheads, to represent the new power of the atomic bomb. The “importance of the new atomic bomb is so tremendous that [Truman felt that] some symbolic reference to it should be incorporated into the flag,” Clark Clifford, a military aide, noted at the time. But Truman changed his mind and the idea was dropped.) The only changes to the presidential seal since then came in 1959 and 1960, when a 49th and then a 50th star were added to the seal to represent the admission of the states of Alaska and Hawaii to the Union.

“I am a firm believer in the people. If given the truth, they can be depended upon to meet any national crisis. The great point is to bring them the real facts.”

—Abraham Lincoln

Octopuses can’t be inoculated against disease.