Preface

In the Beginning

The paranormal has always fascinated me. When I was a child, it also terrified me—especially the idea of ghosts. Indeed, it was not until fairly late in my childhood, maybe at the age of ten or eleven, that I was able to sleep on my own without a nightlight. Despite the terror that thoughts of spooks and bogeymen could often ignite in my childish imagination, my fascination for the paranormal would tempt me to read scary short stories or watch spooky TV programs—activities that I sincerely regretted later as I lay awake in my bed trying to get to sleep, listening out for any noise that might indicate an unwelcome nocturnal visitor.

In my teenage years, my interest in the paranormal widened and my fear of ghosts subsided somewhat. I became interested in many other aspects of the paranormal, particularly the books of Erich von Däniken,1 who argued that evidence strongly supported the idea that our planet had been repeatedly visited in the past by advanced alien civilizations. As a curious and somewhat nerdy teenager, I was totally taken in by von Däniken’s arguments and “evidence.” I naively believed that it must be true because it was written in a book. I was somewhat surprised that many people did not find von Däniken’s ideas as fascinating and mind-blowing as I did. Having said that, clearly enough people shared my perspective to ensure that his books sold in the millions. It was not until many years later that I came across critiques such as Ronald Story’s The Space-Gods Revealed: A Close Look at the Theories of Erich von Däniken and fully appreciated how shoddy von Däniken’s arguments were and how frankly dishonest his presentation of evidence was.2

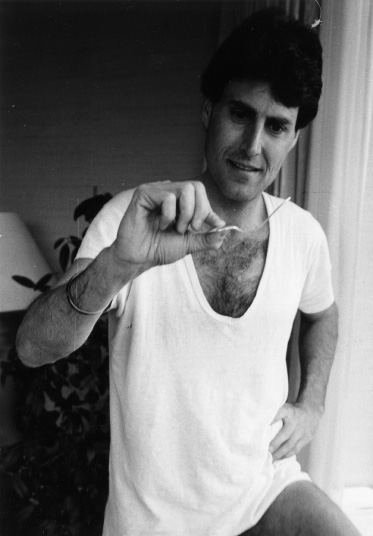

Another memorable moment in my gullible teenage years was the appearance on British TV screens in 1973 of a certain Uri Geller.3 Geller appeared to have amazing psychic abilities. He could apparently read minds, divine the contents of sealed envelopes, fix broken watches with the power of his mind, and, most notably of all, bend metal objects such as forks and spoons merely by gently stroking them (see figure P.1). From the outset, some scientists, including British physicists John Taylor and John Hasted, endorsed Geller as having genuine paranormal ability (although Taylor subsequently changed his mind).4 At the time, I too was totally convinced of Geller’s powers. I so wanted him to be genuine.5

In 1974, I went to Manchester University to study for a BSc in psychology. The topics covered in this book were rarely, if ever, covered as part of my undergraduate degree. After graduating in 1977 and working for a short period as a research assistant at the University of Bangor in North Wales, I embarked on a period of postgraduate research at the University of Leicester under the supervision of Dr. J. Graham Beaumont. My PhD was not in the area of anomalistic psychology. Indeed, I had never heard of anomalistic psychology at that time, not least because the term had yet to be invented. Instead, my research used electroencephalography (EEG) in a largely unsuccessful attempt to study the function and anatomy of the cerebral hemispheres of the human brain.

The Turning Point

I can remember fairly precisely when I stopped believing in the paranormal—and what caused me to do so. After I completed my postgraduate research, I took up a one-year post as a lecturer at Coventry Polytechnic (now Coventry University). As I recall, it was during this period that a friend recommended to me a newly published book called Parapsychology: Science or Magic? by Canadian social psychologist James Alcock.6 It was the first detailed academic critique of parapsychology that I had ever come across. It also put forward plausible nonparanormal explanations for a range of ostensibly paranormal experiences. As my friend had suspected, I loved the book—but I had no idea how massive a role it would play in my life. It opened the door to a whole new world of skepticism that I had never suspected existed.

Figure P.1

When Uri Geller appeared on TV in the UK in the 1970s, millions of people (including the author) were convinced that he possessed genuine psychic powers, including the ability to bend metal by gently stroking it.

Back then, just like today, there were vastly more uncritical pro-paranormal books, articles, and TV and radio programs than skeptical treatments of the paranormal. If anything, the situation was even more biased in favor of paranormal claims than it is today. However, it turned out that there was some skeptical literature out there if only you knew where to find it. I noticed lots of references in Alcock’s book to a publication called the Skeptical Inquirer. I cannot now remember how I did so, but I managed to track down Mike Hutchinson, the UK distributor for this American magazine, and take out a subscription. When an issue arrived, I would eagerly read it from cover to cover.

Some Early Influences

Alcock’s book also made me aware of the work of James (“The Amazing”) Randi. Many readers will no doubt already be aware of this larger-than-life individual, but I confess that back then, in the early 1980s, I was not. I now know that if skeptics were allowed to have patron saints—which of course we’re not—James Randi would probably occupy that role.7

Randi truly lived up to the word amazing in his stage name. During his long career, he had, for example, performed as a conjurer in a carnival roadshow and subsequently in many countries around the word, written an astrology column under the pseudonym of Zo-Ran for a Canadian tabloid (he did this by simply shuffling astrology items from other newspapers and randomly pasting them into his column), escaped from safes and prison cells on numerous occasions, remained submerged in a sealed metal coffin in a swimming pool for 104 minutes, appeared in and hosted numerous radio and TV programs, performed as both a mad dentist and executioner on Alice Cooper’s Billion Dollar Babies tour, and escaped from a straitjacket while suspended by his feet above Niagara Falls. Anyone who would not describe such a career as “amazing” is in serious need of a good dictionary. But it is not for achievements such as these that Randi is held in such high esteem within the world of skepticism.

Born in 1928, Randi retired as a performing conjurer at the age of sixty having achieved international recognition for his skills in that domain. But by this time he had also achieved recognition as a skeptical investigator of paranormal claims. He first came to prominence in this role back in the early 1970s, when a certain Uri Geller was the focus of the world’s media with his sensational claims of amazing paranormal abilities. Randi challenged these claims, accusing Geller of being a fraud and a charlatan who used nothing more than standard conjuring techniques to achieve his effects. I have a vague memory (which may or may not be a false memory) of seeing Randi on television at this time, demonstrating Geller’s most famous feat of apparently bending a piece of cutlery, often to the point where the bowl of the spoon would become detached from the stem, just by gently stroking it. While not revealing how it was done, Randi insisted it was simply a magic trick. At that tender age, I saw Randi’s performance as entirely irrelevant. Okay, so you can do something as a magic trick that looked the same as what Geller was doing. But Uri wasn’t doing a magic trick, was he? He was using his psychic powers to achieve the effect. Dumb or what?8

I now have quite a few friends who are professional conjurers and, as they point out, if Uri really is using psychic powers to achieve the effect, he’s doing it the hard way—it really does look exactly the same when done as a magic trick!9 It should be noted that Geller has never managed to successfully perform this allegedly psychic feat under properly controlled conditions that would rule out the possibility of achieving the effect through the use of conjuring techniques.

As I look back some four decades or so, I can now more fully appreciate the influence that a number of other skeptics had on my own thinking even though I was not so aware of it at the time. I can no longer remember where or when I met most of them, or even the order in which I met them, but each made an impression in their own way. Prominent among them would be Dr. Susan Blackmore. Sue was certainly the most recognized and well-informed skeptic on the UK scene when I first became aware of her back in the 1980s. Extroverted and articulate, she often appeared on TV presenting the skeptical perspective on a range of ostensibly paranormal phenomena, sometimes with her hair dyed three different colors.

Like me, Sue had been a strong believer in the paranormal for many years before embarking on her own parapsychological research, in her case at the University of Surrey. Her belief in the paranormal had been reinforced by a profound out-of-body experience (OBE) she had had as a student in Oxford in 1970, brought on by a combination of tiredness and mind-altering substances.10 She began her PhD research at Surrey convinced that she could produce strong scientific evidence to prove the existence of extrasensory perception (ESP) despite the general skepticism of the wider scientific community. Several years later, after expending much time and effort on this quest, she ended up as a vocal skeptic. The fact that she arrived at this skeptical position after years of research in the area was pretty compelling evidence to me that maybe ESP did not exist after all.

It was also around this time that I met Richard Wiseman. In contrast to Sue and myself, Richard had never been a believer in the paranormal but had always been fascinated by paranormal claims. His other obsession growing up was conjuring (which may go some way toward explaining why he was always skeptical about the paranormal). He is now a member of the Inner Magic Circle, although he decided that a career as a professional conjurer was not for him and instead registered for a degree in psychology at University College London. If my memory is correct, I met Richard shortly after he had completed his PhD at the University of Edinburgh, under the supervision of the first holder of the Koestler Chair in Parapsychology, the late Professor Robert Morris.

Richard is currently the holder of the UK’s only chair in the public understanding of psychology (at the University of Hertfordshire) and is one of the most recognizable British psychologists today. Not only is he an extremely gifted communicator of science, often appearing in the media, but he is also very, very funny. He has over 130,000 followers on Twitter (I just checked), his books have sold over three million copies, and he has been described by Elizabeth Loftus (Past President, Association for Psychological Science) as “one of the world’s most creative psychologists.”11 Not surprisingly, I hate him (joking—he’s actually one of my favorite people to hang out with).

As I began attending skeptics’ conferences, I was also lucky enough to meet Professor Ray Hyman, an American psychologist whose writings I was already familiar with. Ray is respected by those on both sides of the debate regarding the existence of paranormal abilities because his criticisms of parapsychology, like Jim Alcock’s, are based on a detailed knowledge of the field in contrast to the superficial and ill-informed dismissal that unfortunately is all too common among some skeptics. I confess I was somewhat in awe of Ray, but he turned out to be one of the friendliest people you could hope to meet.

Ray was a founding member of a group called the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal back in 1976. CSICOP is usually pronounced “psi cop,” which seems appropriate given that psi is often used as a general term to collectively refer to all types of paranormal ability. The group was founded in response to what was perceived to be an upsurge in interest in the paranormal in the United States at that time. Other founding members included Paul Kurtz, Martin Gardner, James Randi, Carl Sagan, and Isaac Asimov. As well as publishing the Skeptical Inquirer and organizing skeptics’ conferences, CSICOP members often provided skeptical commentary on paranormal claims in the media.

In 2006, CSICOP changed its name to the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry (CSI; not to be confused with the TV program of the same name). This name change came about partly because it made clear that “the paranormal” was, even in those early days, only one area of interest to CSICOP. In the words of Kendrick Frazier, editor of the Skeptical Inquirer:

our underlying interest has never been the paranormal per se, but larger topics and issues such as how our beliefs in such things arise, how our minds work to deceive us, how we think, how our critical thinking capabilities can be improved, what are the answers to certain uninvestigated mysteries, what damage is caused by uncritical acceptance of untested claims, how critical attitudes and scientific thinking can be better taught, how good science can be encouraged and bad science exposed, and so on and on.12

Moving On

After I completed my contract at Coventry Polytechnic, I was fortunate enough to take up a two-year post back at Leicester University, working on a project on automated assessment for my former supervisor, Dr. Beaumont. Next, I worked for a year as a research fellow in the psychometric research unit at Hatfield Polytechnic (now the University of Hertfordshire). Although I believe that psychological tests can be useful, the idea of spending the rest of my academic career as a psychometrician did not set my heart pounding.13 For me, it is not one of the most exciting areas of psychology. And so it was with great relief and gratitude that, in 1985, I accepted the offer of a permanent lectureship at Goldsmiths College, University of London.

At this point, my interest in skepticism was still more a hobby than a serious research interest, but I did feel I knew enough to contribute a two-hour lecture critically assessing parapsychology to a module on theoretical issues as part of our BSc (Hons) psychology program. The students appeared to enjoy the lecture, and I continued to give it once a year for the following few years. In 1990, I presented a paper on cognitive biases associated with paranormal belief at the British Psychological Society’s (BPS) annual conference in Swansea. Two years later, I published a version of that paper in The Psychologist, the BPS’s monthly magazine.14 This was the same year that I published my first empirical paper on paranormal belief. You may have missed it? It was in the Australian Journal of Psychology.15 Thus, I took my first tentative steps as a researcher in anomalistic psychology.16

In 1994, I realized that I knew enough to put on a whole module on anomalistic psychology as an option for our final-year BSc students. Originally, I gave my module the title “Psychology, Parapsychology and Pseudoscience” (much later, I revised the syllabus and gave it the title “Anomalistic Psychology”). It proved to be very popular with the students, and I thoroughly enjoyed teaching it. As you might guess from the title, although many of the lectures did cover paranormal topics, I also wanted to be able to cover additional topics such as homeopathy, cold fusion, and N-rays.

Over the next few years, I published a few more papers in the field of anomalistic psychology, but I was aware of the fact that my interest in “the weird stuff” was only tolerated by my then head of department, not actively encouraged.17 I was pretty much explicitly told that I could carry on publishing the occasional paper on paranormal belief and related topics so long as I mainly published in more academically “respectable” areas. I meekly did what I was told and continued to publish on more conventional topics (such as the relationship between cognition and emotion and the functions of the cerebral hemispheres) as well as in the area of anomalistic psychology.18

With the benefit of hindsight, I wish I had been more courageous and just concentrated on the area that interested me the most. Although the more conventional topics that I was researching were genuinely interesting and important, they did not hold the same fascination as the paranormal. Furthermore, whereas many dozens of researchers all around the world were engaged in investigating these more mainstream topics, there were only a few active researchers in anomalistic psychology. The idea of being a big fish in a small pool, as opposed to an average-size fish in an ocean, certainly had an appeal, and I was already more widely known for my weird research than for my more conventional stuff despite, at that stage, having published relatively little in the area. Furthermore, people like Susan Blackmore and Richard Wiseman were living proof that it was possible to have a (more or less) respectable academic career in the area.

Back in those days, it was quite common for academic colleagues to view research in anomalistic psychology as being pretty much a waste of time. After all, they would say, we all know that ghosts don’t exist. We all know that ESP isn’t real. We all know that people aren’t really being abducted by aliens. So why are you interested in this stuff?

This always seemed to me to be rather missing the point. As discussed further in chapter 1, most nonscientists do believe in the paranormal, and a sizable minority of the population claim to have personally had paranormal experiences. Furthermore, such beliefs and experiences have always been reported throughout history in all known societies. Clearly, they are part of what it means to be human. Their ubiquity might indicate that paranormal phenomena really do exist. If so, the wider scientific community should study them in the same way that scientists investigate other natural phenomena. But if, in fact, psi does not exist, then we can learn a great deal about human psychology by investigating the factors underlying experiences that appear to be paranormal even though they are not.

(At Least) Two Types of Skepticism

In most situations, humans prefer simplicity over complexity. We all have a natural tendency to perceive and think about the world around us in simple binary terms such as good versus bad, right versus wrong, us versus them.19 This is understandable. It makes decision-making much easier if we can immediately see the correct course of action in any given situation. The only snag is that the world around us is in reality complex and nuanced. As Algernon Moncrieff, a character in Oscar Wilde’s play The Importance of Being Earnest famously said, “The truth is rarely pure and never simple.”20

Looking back now at some of the views I held about the paranormal when I first discovered the joys of skepticism, I am very much aware that I was a victim of such black-and-white thinking. For example, I would pretty much have agreed with all of the following statements.

- • Most (if not all) people who claim to be psychic (as well as astrologers, tarot card readers, practitioners of alternative medicine, and so on) are deliberate frauds, knowingly deceiving their clients for monetary gain, or else suffering from some sort of psychopathology.

- • Most (if not all) people who claim to have personally experienced the paranormal are either stupid, lying, or suffering from some sort of psychopathology.

- • Most (if not all) experimental parapsychologists are either incompetent when it comes to experimental design and statistical analysis or knowingly fraudulent.

I would not endorse any of those views now. Having said that, there is certainly a grain of truth in each. The history of psychical research is indeed littered with examples of frauds claiming to possess paranormal abilities, and there are many notable examples on the modern scene (although one must be careful when it comes to naming names, as being on the receiving end of a libel case can be very expensive even if one ultimately wins the case).

Every year, many con artists stand trial for defrauding their victims, having based their deception on a claim that the victim was cursed—and that the fraudster could lift the curse in return, of course, for a substantial sum of money. But my personal opinion is that the vast majority of those who claim psychic powers genuinely believe that they possess them. They are fooling themselves as much as, if not more than, they are fooling others.

When it comes to those reporting paranormal experiences, the evidence is pretty clear that those making the claims are typically not stupid, lying, or mad.21 True, some studies investigating the correlation between intelligence quotient (IQ) and paranormal belief have reported small but significant negative correlations, but some find no such correlation. Equally, there is little doubt that sometimes people do knowingly lie about having had a paranormal experience. But we now know enough about anomalistic psychology to be certain that many ostensibly paranormal experiences can be caused by a range of psychological factors that lead the claimant to sincerely believe that they have had a genuinely paranormal encounter. Finally, studies do indeed consistently show significant correlations between paranormal belief and reports of paranormal experiences, on the one hand, and a range of measures of psychopathological tendencies, on the other. But such correlations are small and account for only a fraction of the variance associated with levels of paranormal belief. Besides, given the high levels of paranormal belief within society (see chapter 1), it would seem somewhat perverse to insist that paranormal belief is necessarily an indication of psychopathology.

My belief that parapsychologists are typically incompetent scientists was revised simply as a result of actually meeting and getting to know several of them (and, to a lesser extent, actually reading reports in parapsychology journals). When it comes to fraud on the part of parapsychologists, there are indeed several notable cases in the history of the field—but the same can be said for all other branches of science, including psychology.22

One notable example of a parapsychologist who influenced me to revise my negative view of parapsychology was the late Professor Bob Morris. Bob was, as stated, the first holder of the Koestler Chair of Parapsychology in the Koestler Parapsychology Unit (KPU) at the University of Edinburgh, taking up the post in December 1985, just a couple of months after I started at Goldsmiths.

If my memory is correct, I first met Bob at the Fifth European Skeptics Conference at the University of Keele in 1993. I was impressed and, I must admit, rather surprised that an actual professor of parapsychology would turn up at a skeptics’ conference, given most skeptics’ generally antagonistic attitude toward parapsychology. However, Bob went one better than that. When it became apparent that one of the keynote speakers was not going to be able to attend after all, Bob stepped into the breach and delivered an excellent overview of his approach to parapsychological research. It was clear that he was well aware of skeptics’ concerns about such research and was committed to trying his hardest to meet those concerns.

The more I got to know this likable American over the years, the more I appreciated his open-minded approach. Bob and his team at the KPU devoted much time and effort to directly testing paranormal claims. However, they devoted almost as much time and effort to investigating psychological factors that may lead people to believe they have experienced the paranormal when, in fact, they haven’t. In other words, they were as interested in (and as knowledgeable about) anomalistic psychology as they were about parapsychology.23 Bob actively encouraged skeptics such as myself to visit his lab and to point out any weaknesses we could detect in their experimental methodologies so that they could be eliminated. I realized from my encounters with Bob that parapsychologists were not, in general, the incompetents that many skeptics assume them to be. In some respects, such as the need for double-blind methodologies, parapsychologists were often ahead of more mainstream sciences (including psychology).

For those who knew him, both believers and skeptics, Bob’s sudden and unexpected death in August 2004 came as a real shock. Only a couple of weeks before this tragic news broke, I had been hanging out with Bob and enjoying his wicked sense of humor at a parapsychology conference in Vienna, blissfully unaware that his days were numbered. His legacy lives on, though. Bob supervised many postgraduate students, including, as mentioned, Richard Wiseman, many of whom went on to successful academic careers. Professor Caroline Watt, the current holder of the Koestler Chair of Parapsychology was another of Bob’s postgraduate students. Like him, she is a great example of a truly open-minded approach to the paranormal and, as a result she is also respected by those on both sides of the psi controversy.

Looking back, I can see that when I first rejected my pro-paranormal beliefs, I went from being a believer to what I now view as being a rather dogmatic and dismissive skeptic. Tribal thinking is natural for humans, and in those early days of skeptical discovery I rather enjoyed viewing all self-proclaimed psychics as con artists, all parapsychologists as either incompetent or dishonest, and all believers as either stupid or crazy. I had found my tribe, and we were the good guys—honest, rational, and, most importantly, right. I was certain of it and did not much like those occasional skeptics I had come across who seemed to believe that things were a bit more complicated. Of course, now I have turned into one of those people.24

The Anomalistic Psychology Research Unit

From 1997 to 2000, I did a stint as head of department. At Goldsmiths, it is standard for different staff members to each serve a three-year term as head before passing the responsibility to the next victim. This system is sometimes referred to as a “rotating head” system, which always brings to mind that famous scene from The Exorcist.

As any head of department will tell you, the administrative responsibilities are very time-consuming, leaving little time for research if you happen to be less than superhuman. In recognition of this, the college provides the head of the psychology department with a research assistant for three years. I employed Kate Holden in that role, and it was in discussions with Kate that the idea of establishing a unit at Goldsmiths dedicated to the study of anomalistic psychology first arose. In 2000, the Anomalistic Psychology Research Unit (APRU) was founded.

Among the stated aims of the APRU was to raise the academic profile of anomalistic psychology. I think that we can reasonably claim to have had some success in meeting this aim. As mentioned previously, when I was first interested in this field, it was quite common for colleagues to view it as not “academically respectable.” Although I still come across such attitudes occasionally, it is much less often. One way we attempted to achieve this aim was to primarily publish our findings in mainstream psychology journals rather than parapsychology journals. Although I have no objections to publishing in the latter, the sad truth is that mainstream science journalists pay very little, if any, attention to such journals regardless of the quality of their contents.

The Skeptic Magazine

By the year 2000, there were several regular magazines for skeptics, including the aforementioned Skeptical Inquirer (founded in 1976 and published by CSI, formerly known as CSICOP) and Skeptic (first published in 1992 by Michael Shermer’s Skeptics Society). In the United Kingdom, Wendy Grossman founded The Skeptic magazine in 1987, just around the time that I was first discovering the delights of skepticism. I was an early subscriber. I don’t recall exactly where and when I first met Wendy, and neither does she, but it was inevitable that we would become friends given our shared interests.

Wendy edited the magazine for the first few years before handing the baton on to Toby Howard and Steve Donnelly, who edited it for the next ten years or so. The British magazine always depended on the enthusiasm and goodwill of the editors and a small army of volunteers to help in its production. It took a lot of time and effort to produce each new issue, and so, perhaps inevitably, busy people like Toby and Steve eventually decided that they had done their bit and wanted someone else to take the reins. Somewhat reluctantly, Wendy agreed to a second stint as editor.

In 2001, I coedited (with Kate Holden) a special issue of the magazine devoted to the work of the newly founded APRU.25 Not long after that, I finally gave in to Wendy’s persuasion and took over the role of editing the magazine on a longer-term basis, along with a series of student coeditors.26 I did so for the next decade or so. Like those who had gone before me, I found the job both a blessing and a burden. On the positive side, it raised the profile of the APRU and put us right at the center of the UK skeptic scene. I have no doubt that it raised my own profile somewhat, given that I could now be presented in the media not only as a professor of psychology at a London University but also the editor of the UK’s longest-running skeptical publication. On the negative side, it was always difficult to find the time, given my other commitments as a full-time academic, to put each issue together, even with the help of numerous volunteers.

Each time a new editor took over, they would typically give the mag a makeover and improve its appearance somewhat. In our case, to mark the magazine’s twenty-first anniversary, we introduced full-color covers, typically featuring fantastic caricatures, by the talented artist Neil Davies, of someone interviewed for that edition.

We also established an editorial advisory board that read like a who’s who of modern skepticism, including academics (such as Richard Dawkins and Brian Cox), writers (such as Simon Singh and Ben Radford), comedians (such as Stephen Fry, Tim Minchin, and Robin Ince), and conjurers (such as James Randi and Derren Brown). We knew that in reality these busy people would not have much time to devote to the magazine, but we were grateful that they were willing to have their names listed in each issue to indicate that they shared the values of the magazine, summarized in our tag line: “pursuing truth through reason and evidence.”

Eventually, I decided that I too had done enough and passed the job on to Deborah Hyde. Deborah has a much better talent for design than me, and she introduced further innovations after she took over in 2011. For example, she introduced full color throughout the magazine. She would also often include as a centerfold work by Crispian Jago, such as his wonderfully satirical (yet informative) illustrations of the Venn Diagram of Irrational Nonsense and the Periodic Table of Irrational Nonsense.

In collaboration with Neil Davies, Crispian produced a wonderful set of Skeptic Trumps cards based on the popular children’s card game Top Trumps (see plate 1).27 Each card featured a caricature and brief description of an individual active in the world of skepticism and listed their special power, weapon of choice, key output, and archnemesis. I was naturally chuffed to be included and find myself in the company of so many of my personal heroes. It took a little while for me to realize that I seemed to have just about the lowest scores of everyone featured. For example, my special power of “Hitting paranormal claims with a large science and reason stick” earned me a mere 63 percent—whereas Simon Singh was awarded a massive 88 percent for his special power of “Casting the shadow of a pineapple with his head”! Oh well, at least I’d been included.

The Skeptic is currently available for free, online only, ably edited by Michael Marshall, project director of the Good Thinking Society, supported by an editorial team from the Merseyside Skeptics Society.28 I continue to write articles for the magazine.