2

Waking Nightmares

A Gentleman Pays a Call

The following is an account of a strange experience that happened to my friend Sarah Elizabeth Cox. At the time, Sarah was a university press officer and part-time postgraduate student. She was thirty-two when this happened to her.

To my memory this has only occurred to me once, in 2019. I was in my flat alone in Catford and sleeping. I was particularly stressed out because of the noise from my upstairs neighbour. I’d lived there about six months, and he made a huge amount of noise at night, banging on the floor, talking loudly on the phone for hours on end. Most nights I would sleep in padded ear defenders—it was that bad. I wasn’t drunk as such when I went to bed but had maybe three glasses of wine in the evening, so there was definitely some alcohol in my system. It was during a period where I was probably drinking a lot more alcohol than usual and would have much weirder dreams generally but nothing particularly dark and disturbing.

I remember the door to my flat being wide open (it wasn’t in reality, it was locked and I always double-lock it at night, but it felt very real that it was open into the communal corridor)—the door went straight in to the main living and sleeping space in the studio flat.

A figure came in, tall and hunch-backed, wearing a long black hooded cloak. He didn’t have a face, but the space where the face should have been seemed to kind of glow a dark green. He seemed to be larger than life-size, perhaps around 7 or 8 feet tall, but hunched over. Even though I couldn’t see his face, I felt that he probably did have a face, and would have looked similar to those characters in an episode of Buffy which aired in 1999 when I was 13. I found them particularly scary at that time (especially the way they floated) and I would dream about them a lot in my early teens.

I confess that I was not that familiar with the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer, but Sarah kindly sent me a link to a YouTube clip so that I could see for myself what she was referring to.1 The Gentlemen, as they are called, appeared in “Hush,” the tenth episode of the fourth season of the popular series. This episode is widely acclaimed as one of the best ever by fans of the series. I can see why. The Gentlemen are as creepy as hell! They are pale, silent ghouls with bald heads, sunken eyes, and wide, malicious grins, revealing metallic teeth. They do not walk but instead glide along about a foot above the ground, their legs not moving. They are elegantly dressed in black suits and carry satchels containing scalpels (which are used to remove the hearts of their terrified victims). They communicate with each other using polite, graceful gestures. You would not want these guys in your bedroom. Sarah’s account continues:

The figure stopped at the side of my bed, which is a low platform bed, so he leaned right over me (possibly hovering in the style of the Gentlemen) and let out this god-awful shrieking noise which lasted for what felt like about 30 seconds, perhaps longer, in one long stream. It was a sort of deep guttural sound. I felt like it was imprinted on my brain and I could hear it for days and days afterward. I’m not sure I could replicate the noise myself but I’d recognise it if I heard it.

I felt like I wanted to roll over and shriek back or to punch him in the space where his face should be, but I couldn’t force myself to turn over, so I lay curled up facing the wall and tried to put my right arm over my ear to stop the noise, which seemed to go on forever. I felt like I was shaking from trying to force myself to roll over and also felt really scared that he was going to stab me with a knife in the ear.

I thought it could have been a real person who had broken in and I was about to be attacked. Eventually the noise stopped, and I remember him turning around and leaving the room slowly the way he came in.

Interestingly, I also had an extremely meta and perhaps quite unique experience of knowing exactly what was going on at the time it was happening. I was thinking, “This is terrifying, I’m about to be attacked” but also, “Wow, this is sleep paralysis, isn’t it? I know all about this because of Chris and Alice! Weird that this has never happened to me before but there’s a first time for everything.” So, there was this level of awareness about what was happening which I thought was quite interesting (and funny the next morning, perhaps not at the time).

I remember the sound of the shriek a lot more clearly than everything else.

Sarah actually realized what was happening to her as it was happening because she had already had conversations about sleep paralysis with me and another colleague and friend at Goldsmiths, Professor Alice Gregory. Alice is an expert on sleep in general and has carried out research into the topic of sleep paralysis with me, along with Dr. Brian Sharpless and Dr. Dan Denis, both leading international experts in the field. But Sarah was mistaken in thinking that her experience of recognizing what was happening to her as it happened was unique. In fact, it is quite common—and I have even had previous reports of people telling me that, during the experience itself, they have thought, “Oh, I must tell Chris French about this one!”

Sarah had sent me her account in response to an appeal I had sent out on Twitter just before I started writing this chapter. I know that such firsthand descriptions really bring to life the topic of sleep paralysis. I also know from experience that people who suffer from sleep paralysis—especially in its vivid form as exemplified above—are usually quite keen to share their experiences as they, perhaps more than anyone else, want to make sense of what can be a profoundly disturbing experience. For example, I wrote a column on the topic for the Guardian’s science pages back in 2009 and was overwhelmed by the number of comments from readers wanting to share their own stories.2

Not all episodes of sleep paralysis are as scary as Sarah’s. Indeed, it is far more commonly experienced as simply a temporary period of paralysis, lasting perhaps a few seconds, occurring between sleep and wakefulness. It is typically a little disconcerting but, in its mild form, likely to be quickly (and correctly) dismissed as being nothing to worry about. As we shall see, however, it can sometimes be much more terrifying and can, in some rare cases, seriously impair a person’s quality of life.

The Terror That Comes in the Night

The title of this section is taken from folklorist David J. Hufford’s classic book on the topic of sleep paralysis, subtitled An Experience-Centered Study of Supernatural Assault Traditions.3 That book is required reading for anyone with a serious interest in the topic, along with the excellent volumes by Shelley R. Adler and Brian A. Sharpless and Karl Doghramji.4 Before delving a little deeper into the science of sleep paralysis, I would like to present a few more firsthand accounts. I find reading such accounts endlessly fascinating, and I am always struck by the fact that what we are dealing with here is a common core experience overlaid with peculiar idiosyncratic elements. The main thing to bear in mind when reading these accounts is that, however we might interpret what is going on, these are real experiences happening to real people.

As stated, sleep paralysis in its mild form consists of nothing more than a temporary period of paralysis as one is drifting off to sleep or emerging from it. However, it may be accompanied by a number of other symptoms that can serve to make it altogether more terrifying. The first of these is an overwhelming sense of presence. Even though the sufferer may not be able to see or hear anything threatening in the room with them, they are convinced that someone—or something—is definitely there. Furthermore, whoever or whatever it is, it has extremely malign intentions toward its helpless victim. A good example of this phenomenon was sent to me by Ian Gardiner:

My particular experiences were over a few months about 26 years ago when I was in my early 30s. I would wake up in the early hours, always lying on my right side. I knew that I was awake as I was aware of reading the time on my bedside clock radio. I was unable to move and shortly after waking I would be overcome with a sense of appalling dread which grew greater as time passed.

Our bed was against the back wall of the bedroom and the door was at the bottom left corner (as viewed from the bed). So as I woke I could not see the door but had this overwhelming sensation that someone or something was in the doorway watching me. It was a horrible sensation which I can still bring to mind all these years later. I tried to shout to alert my wife but could not speak. The fear was one of impending doom or the fact that someone was “coming for me.” Gradually the paralysis would ease off and I was able to move again. The first thing I would do would be to look over at the doorway. There was never anything there.

I have had no episodes since that time and cannot put a finger on any reason why they might have started or indeed why they stopped when they did. As I recall an episode would last for between 1 and 2 minutes. Even though this was 26 years ago, the memories are still clear in my mind.

Here is another account in which the sense of presence is a dominant feature. This one was sent to me by Matt Salusbury and includes a description of a second common feature of such episodes: a sense of pressure on the chest.

I had one back in 1986. I was 18. I was travelling in the US during the summer, staying with some distant Japanese relatives in Michigan State University, Ann Arbor, Michigan. I slept on their sofa, which may have had something to do with the incident that followed. I woke up one night, I seem to remember a light had been left on in the kitchen/living room I was staying in. The first sensation I had on waking was that I couldn’t move, I was being firmly pinned down onto the sofa with quite a lot of force and pressure.

Very soon afterwards I had the sensation that there was something very evil standing just out of my field of vision, immediately behind my head. I can’t recall whether I actually sensed something visually in my peripheral vision, I suspect not, or was just aware of some malevolent entity that I couldn’t physically see, but could somehow sense. The pressing down on my chest and my complete inability to move felt like part of that evil and malevolence, this entity was causing it.

I sensed that it was some kind of tall entity, in some way skeletal, like H. R. Giger’s alien design from the Alien movies, or Judge Death in his helmet from Judge Dredd. There was some sort of gristle and muscle between the bones, particularly around the teeth and what was left of the jaw, but I couldn’t see a face. I can’t recall the colour, except for the white teeth with the raw flesh of the gums around it, as if the skin of the face and lips had been peeled away.

I didn’t know whether it had seen me, or seen whether I was awake, or I was in denial about whether it could see me. I closed my eyes tightly, trying to pretend I was asleep, somehow feeling that if it didn’t know I was awake it might not react and might leave me alone. I remember thinking what a lame and hopeless plan this was, but desperately trying to pretend I was asleep, it was for some reason very important that I did. I was absolutely terrified, perhaps the most scared I’ve ever been in my life.

I remember initially trying to cry out, but being unable to make a sound.

Somehow, I managed to get to sleep. I woke up the next day and the daylight came flooding in, it seemed almost impossible that the experience of the previous night had happened. So unlikely, in fact, that I didn’t mention it to my hosts. I had a sneaking suspicion that there was a perfectly logical explanation.

I can’t recall how long the experience seemed to last, I do remember lying there in complete terror with my eyes tightly closed for an awfully long time, perhaps hours, before I eventually drifted off to sleep.

Matt refers to a third extremely common feature of sleep paralysis episodes: intense fear. Now, you may be thinking, not unreasonably, that intense fear is a perfectly understandable reaction to the terrifying experiences described, and it would be hard to argue with that. However, it has been suggested by J. Allan Cheyne and colleagues at the University of Waterloo in Canada that the intensity of the fear experienced is a direct result of activation of the amygdala, the part of the brain that deals with the perception of threat and initiation of the fight-or-flight response.5 Cheyne’s theory will be described in more detail later in this chapter.

It is also interesting to note that in both Sarah’s and Matt’s accounts they felt able to describe what their unwelcome intruders looked like despite maintaining that they could not actually see them. This type of “seeing without seeing” is not uncommon in sleep paralysis episodes. However, some sufferers do actually experience vivid visual hallucinations (see figure 2.1). Garret Shanley here describes a couple of sleep paralysis episodes from his childhood. The first of these features the “Old Hag,” a common nocturnal visitor during such episodes.

Up to the age of 7, I experienced the old hag regularly. She resembled the witch from The Wizard of Oz or from an Irish children’s television programme that was on at the time. She wore black and a pointed hat. I would see her in the corner of the room and she would gradually approach me. Rather than feeling paralysed, I remember deciding not to move. I would remain completely still so she would not know I was awake and I would only glimpse in her direction now and again to see how close she was. When she was close, I would keep my eyes shut and feel the weight of her as she sat on my legs. I did not want her to know I was awake in case she spoke to me. Then, exhausted by the terror that would decrease over time, I would eventually fall asleep. I started to question if this was a kind of dream (it did not feel like my other dreams or nightmares at all) when my mother and siblings said it was. I once wedged several books between my bed and a wall so my bed could not be approached without knocking them over. In the morning, they were all knocked down—I suppose they just fell over by themselves, but I heard them falling, slowly, one by one during the night.

The most distressing sleep paralysis experience I had as a child was when a series of faces appeared in a mirror that hung opposite the bed I was in that night—I was not in my usual room. One deformed face of a gurning monster would be replaced by another—over and over, each more horrible than the last. My eyes were glued to the mirror and the faces were accompanied by an intense sound like feedback, but not quite. I thought the faces would become so awful that I’d eventually see one that would drive me insane. I yelled and my mother came to the room.

Garret stopped having sleep paralysis after that, only to start having episodes again in his twenties. His final episode (to date) occurred in his late thirties.

It is not just visual hallucinations that may be experienced during sleep paralysis. As Sarah’s and Garret’s accounts illustrate, auditory hallucinations may also occur. Indeed, it appears that the hallucinations that are experienced during such episodes can potentially affect all sensory modalities. Here is an account from Angela Keogh, a forty-three-year-old secretary for a property company in London with a lifelong history of sleep paralysis. It is an example not only of a vivid tactile hallucination but also of the strange bodily sensations that often accompany episodes and the difficulty of finding the words to properly describe the experience.

It was January this year, the usual thing happens, I feel like something is trying to get into my chest and everything caves in in my chest, with the sensation of something running through my chest like . . . oh, sorry, I don’t think I have the right words for it, but it’s like a build-up of something happening, like I’m falling or going deeper into the sleep paralysis, and I’m not able to move at all, and I really struggle with it. But this time I can see a claw at the end of my bed. The claw/hand looks like it’s made out of sticks or a tree. So all brown and veiny with long brown fingers with sharp nails and I could actually feel it grabbing my foot. I can feel that sensation of it grabbing and the sharp feel on my foot. And then at this stage I literally jump out of bed and I immediately check under the bed. I think that episode happened one or two more times after that. So I started sleeping with my feet away from the end of the bed.

The following account, sent to me by Nell Aubrey, includes auditory, visual, and tactile aspects:

My first really clear memory of having a full episode, as it were, was when I was about 8 or 9. I was staying with my best friend, who lived in a very large old house. I had stayed there plenty of times before, but as her stepbrother was staying I had to sleep in one of the guest rooms, which had a four-poster bed in it. I should point out that I loved the house, and the family, it was really a magical and very happy place, and I spent as much time there as I could and would have moved in with them and never gone home again, if they had let me!

There were some parts of the house that really scared me, but not the four-poster room, and I had longed to sleep in that bed for ages. I mention this to emphasize just how scared I must have been to give up on the opportunity! I remember being very excited to go to sleep there, but becoming quite fearful and agitated once I was alone and in the dark. I had trouble getting to sleep, although that wasn’t unusual. I woke up thinking that someone had called my name, I had a lot of hypno-hallucinations and still do, but I had no idea what they were at that age and they disturbed me a lot.

At first, I thought one of the cats was in the room, and had jumped on the bed, as I felt that kind of a thud on the covers. I couldn’t sit up and that was when I began to feel really scared. I felt something leaning on my abdomen which was very painful and oppressive and at the same time I saw a figure at the foot of the bed, where the curtains were pulled around the bedpost. It was a thin long humanoid shape and it seemed to stretch its arm out over me, and the pain got worse as it did so. I suppose it was pain from feeling I couldn’t breathe properly, but I’m not sure. It lasted quite a long time and then gradually dwindled away. When I could finally move I abandoned the four-poster and went to sleep on the floor of the room next door.

I have come across several accounts in which episodes are initially interpreted as a family pet jumping onto the bed. Indeed, I have myself had one such sleep paralysis experience some years ago. The familiar sensation of feeling the weight of our cat pressing on the mattress was slowly joined by the realization, as I emerged from sleep into full wakefulness, that the cat had died two years previously. It was not a particularly scary experience as, by this stage, I was fully aware of the nature of sleep paralysis. Carla MacKinnon, a filmmaker and friend of mine, describes a very similar experience:

I am asleep in bed when I am woken by a cat jumping onto the bed. It must have jumped in through the window. I am on the third floor. The window is closed. I know it is a black cat although I cannot open my eyes to look. It is padding on the bed and it is not unpleasant, but it is unsettling, and when I try to sit up in bed to deal with the situation I cannot move. I cannot turn over. My whole body is lead. This time I know what is happening, I’ve been reading about sleep paralysis and how it manifests. I relax and as calmly as I can I examine the feelings in my body. Very soon it ends.

It has to be said, however, that this was one of Carla’s least terrifying episodes. Before she became familiar with the nature of sleep paralysis, the experience was often much more frightening. For example:

I awake in bed, next to my boyfriend. It is very dark in the room. In the corner of the room there are two men. I cannot see them but I know that they are there, and what they look like. I can hear them talking. They are talking about murder. I cannot move, my body is frozen but my senses are on high alert. One of the men comes and stands directly above me. I know he is wearing a hat, although my eyes are closed. He spits, and his spit lands in the socket of my closed eye. I can feel the impact, the wetness, the trail of slime.6

It is not uncommon for there to be a strong sexual aspect to these experiences. In some cases, they can even be emotionally positive experiences as the following account from William in Derbyshire illustrates:

I could feel myself lying on the bed and knew that I was in my bedroom. I saw the part of the bedroom that I would expect to be able to see, were my eyes open, e.g. my half of the bed, the window, the wardrobe, but I could feel that my physical eyes were still closed. In addition to seeing what I would expect to be there, there was a young woman standing by the foot of my side of the bed. She wore a fawn pullover with brown stripes and a brown skirt. She had long, thick, brown hair, partly falling down over what should have been her face, but there was just a black void where her face should have been. I recalled having had a previous sleep paralysis experience and remembered that when I’d last had such an experience, it all stopped when I opened my eyes. Sensing that this time, it had the potential to be an enjoyable experience, I deliberately kept my eyes closed, so that the experience would continue. She walked down the side of the bed (towards my head). Without verbalizing the wish, I thought that it would be nice if the woman came and got on top of me. Much to my pleasant surprise, she climbed on top of me. I therefore seemed to discover that one can control such an experience to some extent by willing the ‘intruder’ to do something. As she was kneeling across me, I tried to raise my arms to cuddle her, as I fancied her, but much to my frustration, I could not budge them even a millimetre—I was paralysed. So I had to give up that idea. She then lent forward and her hair fell onto my face—the feel of it was exactly as it would have been, had it have been a real person’s hair. The sensation caused me to ejaculate. When I did open my eyes, of course there was no-one there.

Unfortunately, the sexual side of the experience, when it occurs, is sometimes far from positive, as vividly illustrated by the following anonymous account from a female long-term sufferer:

That’s when the sexual side of it started. I will be brief on this part, but basically with the sleep paralysis came the “rapes.” I mean, obviously they weren’t real. But that is what I could feel happening to my body. The weirdest part of the sexual side was that when I was being raped (so to speak—gosh, that sounds bad, doesn’t it?), the hallucinations made it a bit odd. Basically, I was being turned upside down. So pretty much like a suspended headstand. In my mind, I could feel my hair hanging down and the blood rushing to my head. But I could actually feel something entering me down below. You know I could actually feel something inside me. Weird!! I can’t really remember how long that went on for. But thankfully I’ve been free of that now for at least 6 years or so.

I hope that the accounts provided have given you some indication of the weird and surreal nature of sleep paralysis. But, for those of you lucky enough never to have experienced the more vivid manifestations of this intriguing phenomenon, I recommend viewing Carla MacKinnnon’s award-winning short film Devil in the Room.7 As an animator and long-term sufferer from sleep paralysis, Carla received funding from the Wellcome Trust to support her in making her film, which is partly based on her own experiences. When she first invited me to collaborate with her on this project, she told that she was aiming to produce a film that was “half science documentary, half horror movie.” I think she was 100 percent successful in achieving this.

If you’re brave enough, you might also want to check out The Nightmare, a documentary film about sleep paralysis directed by Rodney Ascher, released in 2015. This is another film that really captures the disturbing nature of this phenomenon, in this case by a mixture of talking-heads-style interviews with eight sufferers and vivid reconstructions of their experiences. My only reservation about this film is that, toward the end of the documentary, all of those involved are asked to give their views on what they think is really happening to them. All but one of them reject the scientific explanation for sleep paralysis and instead opt, to a greater or lesser extent, for paranormal interpretations. The director cannot be held responsible for those views, of course. If that’s what his contributors said, then that is what they said. But I believe that this is not a helpful message to put out to others who are experiencing this perplexing phenomenon. I would prefer to let people know that sleep paralysis, although it can be absolutely terrifying, is essentially harmless—with one possible big exception, to be discussed later in this chapter.

For people who are unaware that sleep paralysis is a scientifically and medically recognized phenomenon, actually experiencing an episode can be extremely frightening and perplexing. Depending on the nature of the episode, a single attack may be dismissed as “some weird kind of nightmare”—albeit one that feels very different from any nightmare previously experienced. Multiple episodes are more difficult to dismiss. The sufferer is likely to consider two main possibilities—either they are “going crazy” or they are experiencing something that is really happening. The latter possibility may sometimes seem marginally preferable to the former.

Sufferers are often reluctant to tell anyone else about their experience because they are afraid, with some justification, that they may indeed be judged to be “crazy” and have to endure the stigma that so often and so unfairly goes along with such labeling. On several occasions, following public talks that I have given, I have been approached by people telling me that they have had the very experience I have described but that they have never told anyone else about it before. The sense of relief that people report on first learning that what they experienced has a scientific explanation is almost palpable.

My aforementioned colleague, Alice Gregory, provides an example of this in her excellent book, Nodding Off.8 I had put seventy-year-old Mrs. Sinclair in contact with Alice after Mrs. Sinclair had contacted me to discuss her sleep paralysis experiences. Living alone in the depths of the countryside, Mrs. Sinclair had eventually been convinced that her 300-year-old cottage must be haunted. For example, in one of her first experiences she had awoken one night with the feeling that someone was trying to strangle her. She had expected to see a burglar upon opening her eyes but instead was shocked to see the face of a childlike imp laughing at her. In Alice’s words:

He began pushing against her sides, tucking the bed sheets in around her. “We’ve nearly strangled you and now we’re tucking you in,” he goaded, in a way reminiscent of bullying children some 60 years previously. She tried to move but instead found herself “tarmacked into the mattress,” paralysed except for the ability to move her eyes. Although non-religious, the petrified Mrs Sinclair began mentally to recite the Lord’s Prayer.9

By the time Mrs. Sinclair contacted me, after several other equally distressing episodes, she had already realized that her cottage was not haunted and that, in fact, she was suffering from sleep paralysis. She had found out more about the topic by consulting reliable sources on the internet. She got in touch with me because she had seen me talking about the phenomenon on daytime TV and realized that I would be interested to hear about her own experiences. She told me that she had been so relieved to learn that she was not being plagued by pesky poltergeists—and that she was not losing her mind!

She had decided, not unreasonably, to visit her doctor to see if he had any advice on how she might reduce the incidence of her episodes. She was still rather nervous at the prospect of talking to anyone about her weird adventures but plucked up the courage to describe them to her doctor, making it plain that she now realized that they were caused by sleep paralysis. Her doctor arrogantly dismissed her on the grounds that he had never heard of sleep paralysis. When I heard this, it made me very angry. Thirty seconds on the internet would have made it clear to this pompous so-and-so that sleep paralysis is actually a scientifically and medically recognized phenomenon. I sent Mrs. Sinclair some papers on sleep paralysis and jokingly suggested that, the next time she visited her doctor, she might like to hit him around the head with them. This is just one illustration of the fact that it is often not just many members of the general public who have never heard of sleep paralysis but also a large proportion of medical professionals.

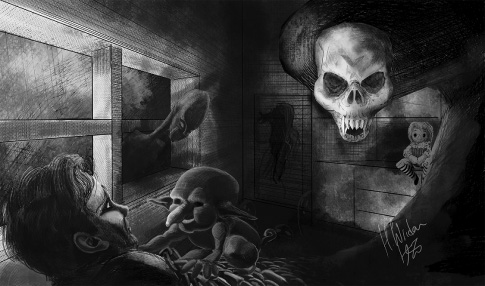

Figure 2.1

During an episode of sleep paralysis, the sufferer may experience nightmarish hallucinations as terrifyingly real. Illustration courtesy of Hawraa Wriden.

What Sleep Paralysis Is Not

Before discussing the defining features of sleep paralysis, we will briefly consider a few common sleep-related anomalous experiences with which it might sometimes be confused. The first and most obvious is the nightmare—or at least the nightmare as that term is commonly understood in modern times. Historically, the term did indeed refer to an experience that corresponded to what we would nowadays call sleep paralysis rather than just being a synonym for “a bad dream.” Even in modern usage, the term should really be reserved for dreams that induce real terror rather than having a slightly negative tone. Dreaming of finding yourself naked in the supermarket or of being stuck in an interminable traffic jam on the M25 do not really fit the bill.

To really count as a nightmare, the dream might involve, for example, the sense of a real threat to one’s very survival or the survival of one’s loved ones. It will be extremely memorable, and the sleeper will be in a state of extreme arousal when they wake up. All of this is likely to also be true for an episode of sleep paralysis, so what are the differences? First and foremost, the latter involves an awareness of the actual surroundings of the sleeper whereas the nightmare does not. Second, paralysis is a defining feature of sleep paralysis whereas this is not the case for nightmares, although they may involve a sense of difficulty moving away from a threat. Finally, on awakening, the dreamer immediately realizes that they have been having a nightmare and that the events experienced did not really happen. The sufferer from sleep paralysis is much less certain that the events experienced did not really happen.

Many of the symptoms of panic attacks are the same as those experienced during sleep paralysis, including intense fear, a rapidly beating heart, sweating, and catastrophic thinking (e.g., “I am going to die”). Furthermore, susceptibility to sleep paralysis is associated with susceptibility to panic attacks, and panic attacks can occur when an individual is emerging from sleep. Thus, the two disorders would be easy to confuse. One big difference is, of course, that someone suffering a panic attack is not paralyzed and will not experience symptoms such as hallucinations and a sense of presence. Finally, the panic felt during a panic attack is unexpected and hits the sufferer in a great rush, whereas that experienced during sleep paralysis typically grows more slowly. Often it is felt to be in response to the other symptoms of sleep paralysis.

Another sleep-related phenomenon that must be distinguished from sleep paralysis is that of night terrors (pavor nocturnis). On closer consideration, night terrors can be seen to be very different from sleep paralysis. Indeed, the only thing they seem to have in common is terror. The sufferer from night terrors will typically scream, leap out of bed, and appear to flee with all their might away from some unnamed terror. The first and most obvious difference between this phenomenon and sleep paralysis is that the sufferer is very definitely not paralyzed. Second, the sufferer typically cannot recall much, if anything, of the episode, whereas the hallucinations experienced during sleep paralysis are all too memorable. Finally, it is extremely difficult for benevolent others to rouse the sufferer from night terrors back into normal wakefulness, whereas sleep paralysis sufferers are easily roused from their torment—and typically extremely grateful to be rescued.

The final sleep-related anomalous experience to be described here is that of the colorfully named phenomenon of exploding head syndrome (EHS).10 EHS refers to a brief hallucinatory experience that occurs just as the sleeper is drifting off into, or emerging from, sleep. Typically, a loud noise is heard, such as an explosion, fireworks, a gunshot, a scream, or a clash of cymbals, but visual sensations (e.g., a flash of light) are also reported in about 10 percent of cases. There are several characteristic differences between EHS and sleep paralysis. First, whereas EHS sufferers report that the jarring sensations wake them up, sleep paralysis sufferers are convinced that they are awake during their ordeal. Second, EHS episodes are short, sharp shocks lasting at most a few seconds; sleep paralysis episodes may last for minutes. Third, the sensations experienced during EHS are nondistinct, whereas the perceptions during sleep paralysis are elaborate and detailed.

Defining Issues

Sleep paralysis is one of four common symptoms of narcolepsy. Together, these four symptoms are often referred to as the narcoleptic tetrad. The other three symptoms are cataplexy (sudden loss of muscle tone often triggered by strong emotion), overwhelming feelings of drowsiness, and vivid hypnagogic hallucinations (that is, vivid hallucinations experienced at sleep onset). Sleep paralysis can also be caused by acute intoxication or as a side effect of withdrawal from certain medications. However, it can also occur in the absence of any of these medical conditions or any other sleep disorder, in which case it should technically be referred to as isolated sleep paralysis (or recurrent isolated sleep paralysis if multiple episodes are being referred to). Brian Sharpless has argued that a useful distinction can be made in the clinical context between those who suffer significant levels of distress or fear as a result of their isolated sleep paralysis and those who do not. The former, he suggests, should be referred to as suffering from fearful isolated sleep paralysis (or, in the case of multiple episodes, recurrent fearful isolated sleep paralysis).11 Most, but not all, of the cases described in this chapter would be examples of this type.

As stated, many members of the general public have never heard of sleep paralysis. If they have a frightening episode themselves, they often have no idea what to make of it. Similarly, if a friend or a family member tells them about an episode that they have experienced, they are at a loss to offer them any explanation or advice. Even worse, as we have seen, many medical professionals have themselves not heard of sleep paralysis, despite it being fairly common among the general population.

Specialists in sleep disorders will be familiar with the condition. The third edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders includes the following criteria for the diagnosis of recurrent isolated sleep paralysis:12

- A. A recurrent inability to move the trunk and all of the limbs at sleep onset or upon awakening from sleep.

- B. Each episode lasts seconds to a few minutes.

- C. The episodes cause clinically significant distress including bedtime anxiety or fear of sleep.

- D. The disturbance is not better explained by another sleep disorder (especially narcolepsy), mental disorder, mental condition, medication, or substance use.

In contrast, the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders contains no mention at all of sleep paralysis.13 As a consequence, the condition is sometimes misdiagnosed by psychiatrists and clinical psychologists, leading to the recommendation of entirely inappropriate courses of treatment (e.g., prescribing antipsychotic medication).

How Prevalent Is Sleep Paralysis?

As discussed elsewhere, the reported lifetime prevalence rates for sleep paralysis vary enormously across studies carried out in different countries.14 For example, a study of prevalence rates in 359 American adults reported a rate of 5 percent.15 In contrast, 62 percent of a sample of sixty-nine adults from Newfoundland, Canada, reported having experienced sleep paralysis at least once in their lives.16 Brian Sharpless and Jacques Barber assessed lifetime prevalence by aggregating data across thirty-five studies, resulting in a total sample size of 36,533.17 They estimated that 7.6 percent of the general population experience sleep paralysis at least once in their lives. However, two particular subgroups report markedly higher prevalence rates: for students, the prevalence rate is 28.3 percent, and for psychiatric patients, it is 31.9 percent. This probably reflects the fact that, in those with an underlying susceptibility to sleep paralysis, it is most likely to actually manifest if sleep patterns are irregular. Both students and psychiatric patients are likely to have irregular sleep patterns, albeit for different reasons.

It is not entirely clear why prevalence rates vary so much from one study to another. It may be that there are genuine differences in prevalence rates across different types of respondents in different countries, but the reported rates are also likely to be affected by the wording of items in surveys or interviews. This possibility was investigated directly by Kazuhiko Fukuda in a sample of 593 Japanese university students.18 Those students who were given a questionnaire asking if they had ever experienced transient paralysis reported the lowest prevalence (26.4 percent) compared to a group who received a questionnaire referring to sleep paralysis as kanashibari, the traditional Japanese folkloric term for sleep paralysis (39.3 percent). Presumably, the students were more willing to respond positively when the question did not seem to imply some kind of medical condition. If the neutral word condition was used in the questionnaire, an intermediate 31 percent of students responded positively. It has been suggested that there may be a general trend for higher prevalence rates to be reported in cultures where the phenomenon is widely recognized to be nonmedical in nature, such as Japan and Newfoundland.

The Science of Sleep Paralysis

Although more research is needed into this perplexing phenomenon, science can already provide a convincing explanation in general terms. To understand what is going on, we must first understand the neurophysiology of normal sleep. At the start of a normal night’s sleep, the sleeper typically progresses through stages, predictably labeled as Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3 sleep.19 As the sleeper moves from one stage to the next, a number of clearly identifiable physiological changes occur, including changes in heart rate, breathing rate, brainwaves, and so on. The sleeper will then begin to reemerge from the deepest stages of sleep into the lighter stages and ultimately into what is referred to as REM sleep. REM stands for rapid eye movement. During this stage of sleep, an observer can actually see the sleeper’s eyes moving rapidly beneath the closed lids. It is during this stage of sleep that the sleeper, if awoken, is most likely to describe being in the middle of a vivid dream. It is also the case that, during REM sleep, the muscles of the body are actually paralyzed—presumably to stop the sleeper actually carrying out the actions of the dream. After spending some time in REM sleep, the cycle begins again.

The cycle typically lasts around ninety minutes and is repeated several times throughout the night. The relative amount of REM sleep to non-REM sleep increases throughout the night. Sleep paralysis episodes can be thought of as glitches in the normal sleep cycle during which, to put it simply, the mind wakes up but the body does not. Thus, the sleeper may be able to open their eyes and clearly see that they are in their bedroom but be completely unable to move.20 Furthermore, they may experience a unique altered state of consciousness in which dream imagery is experienced in combination with the contents of normal waking consciousness.

As described above, normally the sleeper spends some time in non-REM sleep prior to going into the REM stage, so why are sleep paralysis episodes often experienced just as someone is drifting off to sleep? It appears that such episodes are more likely to occur if the sleeper atypically enters straight into the REM stage immediately upon falling asleep. Sleep researchers refer to this as a sleep-onset REM period (SOREMP). Narcoleptics who suffer from sleep paralysis are known to be prone to SOREMPs.21 When narcoleptics prone to sleep paralysis were woken up during a SOREMP, they regularly reported an episode of sleep paralysis, but they did not do so if they were awoken from non-REM sleep or from REM sleep that followed a non-REM period. The claim that the sleep paralysis state is a unique altered state of consciousness that combines both REM consciousness and normal wakeful consciousness is strongly supported by the results of a study by Michele Terzaghi and colleagues.22 They analyzed electroencephalographic (brainwave) data from a fifty-nine-year-old narcoleptic during wakefulness and during different phases of sleep. The pattern recorded during a sleep paralysis episode corresponded very closely to the pattern produced by combining the patterns recorded during eyes-closed wakefulness and that recorded during REM-stage sleep.

J. Allan Cheyne, professor emeritus at the University of Waterloo in Canada, is one of the world’s leading authorities on the topic of sleep paralysis. In 1999, he and colleagues published an influential model of the neuropsychology of sleep paralysis, which, although somewhat speculative, provides a plausible account of the phenomenology of such episodes.23 The model was based on survey responses collected from a student sample and two online samples. These data were analyzed using a statistical technique known as factor analysis, which allows responses that tend to co-occur to be grouped together. This analysis suggested that the various sensations experienced during sleep paralysis episodes could be grouped together into three main factors, which Cheyne and colleagues labeled Intruder, Incubus, and Unusual Bodily Experiences. In addition to identifying these three factors, Cheyne et al. speculated about their neurophysiological bases.

Our brains have evolved to alert us to potential threats in the environment. Even though we may not be consciously aware of it, during wakeful consciousness we are constantly scanning the world around us for potential threats; should such a potential threat be detected, attention will be directed away from ongoing activities and toward the possible threat to allow a proper assessment and the initiation of appropriate approach or avoidance behavior if required. The amygdalae play a major role in dealing with such emergency situations. They are two small, almond-shaped clusters of nuclei, one deep within each cerebral hemisphere, that play a major role in the initiation of appropriate fight-or-flight behavior. Normally, the whole sequence of events, from detecting a possible threat, through identification and assessment, to initiation of appropriate action, takes only a fraction of a second. Cheyne and colleagues argue that heightened activation of the amygdalae may explain the first of the factors that they identified in their study. This possibility is supported by the fact that neuroimaging studies indicate that the amygdalae show significant levels of activation during REM-stage sleep.24

The Intruder factor consists of the sensed presence, extreme fear, and visual and auditory hallucinations. Cheyne and colleagues argue that heightened activation of the amygdalae as one is drifting into or emerging from sleep causes a state of alert apprehension that lasts much longer than it would during wakefulness because there is actually no potential threat to be identified by scanning the surroundings. Because no potential threat can be identified and then properly assessed, the amorphous sense that there is something dangerous nearby can last for seconds or even minutes—hence the overwhelming sense of presence that is such a common feature of sleep paralysis episodes. It is argued that efforts to identify the threat will continue based on both external inputs (such as shadows, ambient sounds, and so on) and internally generated imagery (dreamlike intrusions). The end result is often terrifying visual and auditory hallucinations involving threatening monsters and demons.25

Cheyne and colleagues identified a second factor, consisting of pressure on the chest, difficulty breathing, and pain, which often co-occurred with the Intruder factor. They labeled this factor Incubus. In traditional folklore and mythology, an incubus was a male demon who would typically lie atop a sleeping woman to have sexual intercourse with her. The explanation offered for this group of symptoms focuses on the fact that under normal circumstances breathing can be controlled voluntarily, even though such voluntary control of breathing is not actually necessary. Most of the time we continue to breathe without conscious awareness of our breathing, thanks to involuntary muscles that do the job quite satisfactorily. However, during an episode of sleep paralysis, the sufferer may become aware of the fact that they cannot take control of their breathing, leading them to think that they may be suffocating or being strangled. In fact, there is no real danger of this, as the involuntary system will continue to operate, but the ensuing panic is quite understandable. Strenuous attempts to breathe deeply may cause painful spasms.

Both the Intruder- and Incubus-type experiences imply the presence of another being, one that is perceived as a threat to one’s very survival. It is not unreasonable to suggest that sleep paralysis episodes may be a factor underlying beliefs in demons and other spirit beings that attack individuals while they sleep, as discussed later in this chapter.

The third factor identified, Unusual Bodily Experiences, consists of flying and floating sensations, out-of-body experiences, and sometimes feelings of bliss. In the words of Cheyne et al.:

Respondents indicated that these experiences were rarely the rather passive sensations suggestions [sic] by the term “floating,” but often consisted of more vigorous sensations of flying, acceleration, and even wrenching of the “person” from his or her body. In response to questions about floating sensations respondents spontaneously reported a variety of inertial forces acting on them, which they described as rising, lifting, falling, flying, spinning, and swirling sensations or similar to going up or down in an elevator or an escalator, being hurled through a tunnel, or simply accelerating and decelerating rapidly. . . . Several people reported feeling forcibly pulled or sucked from their bodies, sometimes through the forehead and sometimes through the feet, and one person described a sensation of “falling out of” his body.26

The psychology of out-of-body experiences is explored in more detail in chapter 7, but for now it will suffice to note that the explanation offered by Cheyne and colleagues fits well with recent thinking regarding the most likely explanation of such experiences, whether experienced during sleep paralysis or in other contexts. During wakeful consciousness, the vestibular system coordinates head and eye movements along with other proprioceptive feedback to produce our sense of balance and spatial orientation. Brain areas controlling the sleep-wake cycle are known to be closely associated with such vestibular nuclei in the brainstem. Cheyne and colleagues proposed that activation of these nuclei, in the absence of correlated visual input and head movements, is interpreted as floating or flying. This conflicting interpretation of simultaneously floating or flying above one’s bed while at the same time lying motionless on it is resolved by splitting the phenomenal self and the physical body: in other words, an out-of-body experience. Some people report seeing themselves lying motionless, a phenomenon known as autoscopy. Interestingly, although sleep paralysis episodes are typically reported as being extremely stressful and frightening, those that involve unusual bodily experiences are more likely to be reported as being pleasant and, sometimes, even blissful.

A team led by postdoctoral researcher Dan Denis, including myself and the aforementioned Alice Gregory, has conducted systematic reviews of variables associated with sleep paralysis.27 Among other findings, it was noted that stress and trauma are strongly correlated with incidence of sleep paralysis, as was post-traumatic stress disorder and, to a lesser extent, panic disorder. It is not clear whether such factors have a direct effect on frequency of sleep paralysis episodes, or if they have an adverse effect on sleep quality and thereby have an indirect effect on sleep paralysis frequency. Poor subjective sleep quality has been shown to be associated with sleep paralysis in several studies. In examining this relationship more closely, it was found that sleep latency (that is, how long it takes to get to sleep) and daytime dysfunction (for example, excessive daytime sleepiness) were predictive of sleep paralysis.28 A study by the same group established, as had long been suspected, that there is a moderate genetic influence with respect to susceptibility to sleep paralysis.29

Cross-Cultural Interpretations of Sleep Paralysis

Although there is still much to learn about the science of sleep paralysis, the general outline presented above is well supported by empirical evidence. However, the science of sleep itself is a relatively recent development in human history. Prior to that, it would be natural for sufferers to explain these bizarre episodes in terms of the actions of spirits. This still applies today in many parts of the world and even among those with strong religious beliefs in modern Westernized countries.

Historically, episodes of sleep paralysis were typically described as being nightmares, but, as previously stated, it is clear that the term had a much more specific meaning in past centuries than it does today. Whereas today the term is used to refer to any type of scary dream, in the past it was reserved for experiences involving inability to move, intense fear, and so on—in other words, for episodes of sleep paralysis.

It would be going too far to claim that episodes of sleep paralysis fully explain human belief in spirits, but it is reasonable to suggest that they may contribute to the development and maintenance of such beliefs. The strong sense of presence that is so characteristic of episodes is typically felt to be a sentient being of some sort with definite intentions, usually malign, toward the sufferer. In many cases, strange beings are not just sensed but are actually seen, heard, felt, and even smelled. Furthermore, these beings appear to be able to appear and disappear without leaving any physical traces. What stronger proof is needed of the otherworldly nature of these beings?

In addition to the fact that some episodes of sleep paralysis are readily interpretable as encounters with supernatural beings, they can sometimes, as described earlier, turn into full-blown out-of-body experiences. In such cases, experiencers would feel that they themselves are no longer inhabiting physical bodies but instead have become free-floating spirits, often able to pass through walls and travel huge distances in an instant. An alternative, nonspiritual explanation for the characteristics of the out-of-body experience is presented in chapter 7.

Although such spiritual interpretations of sleep paralysis can be found throughout history, it is also true that there have always been commentators who argued for a more naturalistic explanation. For example, Samad Golzari and colleagues discuss a manuscript written by Persian scholar Akhawayni Bokhari in the tenth century in which Akhawayni argues that sleep paralysis “is caused by rising of vapors from the stomach to the brain.”30

When considered from a cross-cultural perspective, we can see that the same core characteristics of sleep paralysis are reported throughout the world and throughout recorded history. However, the favored interpretation of the experiences and the label applied to them can vary considerably. Brian Sharpless and Karl Doghramji present no fewer than 118 different terms from around the world that refer to sleep paralysis.31 While it might be seen as inevitable that these bizarre experiences would often naturally be interpreted within the framework of the sufferer’s dominant belief system, it also appears that the belief system can sometimes influence the actual content of the hallucinatory images themselves. This is illustrated beautifully by the articles included in a special issue of the journal Transcultural Psychiatry published in 2005. As the editors noted, “As a paradigmatic case for the study of the interaction of culture and biology in psychopathology, sleep paralysis illustrates how cultural elaboration of experience can occur before, during, and after a biologically patterned event.”32

Owen Davies argues convincingly that the records of witch trials and other writings on witchcraft from the early modern period indicate that accusations of witchcraft were sometimes supported by testimony that appears to modern eyes to be describing sleep paralysis episodes.33 For example, consider these testimonies presented during the Salem witch trials:

Robert Downer’s experience occurred after the accused witch, Susan Martin, had said “some She-Devil would shortly fetch him away.” That night, “as he lay in his bed, there came in at the window, the likeness of a cat, which flew upon him, took fast hold of his throat, lay on him a considerable while, and almost killed him.” Bernard Peach also testified that, one night, “he heard a scrabbling at the window, whereat he then saw Susanna Martin come in, and jump down upon the floor. She took hold of this deponent’s feet, and drawing his body up into an heap, she lay upon him near two hours; in all which time he could neither speak nor stir.” When the paralysis finally began to wear off he bit Martin’s fingers and she “went from the chamber, down the stairs, out at the door.” Bridget Bishop was similarly accused. Richard Coman stated that eight years before, while he was in bed, she had “oppressed him so, that he could neither stir himself, nor wake anyone else, and that he was the night after, molested again in the like manner.” John Louder also testified that, one night, after having argued with Bishop, “he did awake in the night by moonlight, and did see clearly the likeness of this woman grievously oppressing him; in which miserable condition she held him, unable to help himself, till near day.”

It was also commonly believed during the Middle Ages that sex-crazed demons would sometimes come and have their wicked way with their sleeping victims. As stated previously, the male version of such demons was known as an incubus (from the Latin incubare, “to lie upon”) and the female version was known as a succubus (Latin for “prostitute”). It was further believed that the demons could transform themselves from the female form to the male form and back again. The idea was that the succubus would collect sperm from a male sleeper, and then transform into an incubus and use the sperm to diabolically impregnate a female victim. As already noted, there is often a strong sexual element to episodes of sleep paralysis, whether the sufferer is male or female. This can sometimes be so intense that women report feeling as though they have been raped during the night.

In many modern societies, spiritual interpretations are still common. David Hufford’s ground-breaking book The Terror That Comes in the Night describes the widespread belief in Newfoundland that sleep paralysis episodes are best explained as an attack by the Old Hag, who sits astride the sleeper’s chest. The unfortunate victims report that they cannot move and feel as though they are being strangled. They are said to have been “ridden by the Hag” or “Hag-rid” (which may be of particular interest to fans of Harry Potter).

In Japan, sleep paralysis episodes are referred to as kanashibari (which literally translates as “bound in metal”).34 In contrast to many modern Western societies, the phenomenon is widely discussed and featured in the media in the form of films, TV programs, books, and even computer games. Anna Schegoleva interviewed a group of Japanese children aged ten to twelve regarding their knowledge and experience of kanashibari.35 She found that almost all of them were familiar with the term and were generally very excited to have the opportunity to talk about it. Perhaps this is not surprising, given the love that many Japanese people have for horror films and ghost stories. A third of the children reported that they themselves had experienced kanashibari. As would be expected, these episodes always involve paralysis, difficulty breathing, and a sense of pressure on the chest, but the details of the hallucinations experienced varied somewhat. In Schegoleva’s words:

Most common visions include: Sadako [a film character], ghosts (obake), unfamiliar people. Some other examples: spiritual photographs, suicides, zombies, burglars, frightening things seen on TV. One of the girls (aged 10) saw sleeping pills falling down from the ceiling; there were so many she could hardly stand the weight. The most impressive is Sadako, the one from the Ringu movie. A female figure in white clothes, limping up to the sleeper, with her face enclosed by long hair hanging down from her head . . .

The appearance of Sadako in many accounts is noteworthy and is reminiscent of the appearance of one of the Gentlemen as described at the beginning of this chapter. It is clear that terrifying creations from the imaginations of fiction writers are capable of taking on a life of their own. The popularity of horror fiction is a clear indication that many people enjoy the thrill of being scared out of their wits. Indeed, when Schegoleva asked the children if they used any strategies to try to prevent such episodes, she was quite surprised by their responses—far from trying to prevent kanashibari, many had tried different techniques to induce it.

These are just a few examples of the various culture-specific interpretations of the same core experience across time and space. There are dozens more, as listed by Sharpless and Doghramji. For example, in China, sleep paralysis is referred to as ghost oppression.36 In Germany, it has been referred to as alpdrück (“elf pressure”) and hexendrücken (“witch pressing”).37 Mexicans speak of se me subio el muerto (“a dead body climbed on top of me”).38 Norwegians are sometimes plagued by Svartalfar (black elves who paralyze their victims with arrows, sit on their chests, and whisper horrible things),39 while the Catalan Spanish are familiar with pesanta (an enormous cat or dog that enters homes and sits on sleepers’ chests).40 One of my personal favorites, because it is so creepy, is the interpretation of sleep paralysis found in parts of the West Indies, where the phenomenon is referred to as kokma. Kokma is said to be caused by the spirits of unbaptized children crawling onto the sleepers’ chests and throttling them.

As will be discussed in more detail in chapter 5, sleep paralysis episodes are also implicated in many cases of alleged alien abduction. In most cases, the aliens are not actually seen during the sleep paralysis episode itself, but, for reasons to be discussed, the episode is taken as evidence that the individual has indeed been abducted by extraterrestrials who then wiped the victim’s memory of any further details. Those details, including vivid images of the aliens themselves, may only be recovered via the application of hypnotic regression and are almost certainly based on false memories rather than events that actually occurred.

The most amusing interpretation I ever came across of the strong sense of malign presence that often occurs during a sleep paralysis episode occurred some years ago. I had been taking part in a radio program about sleep paralysis and was being driven home afterward. My driver asked me what I talked about on the show, so I gave him a brief description of the main features of the phenomenon. “I’ve had that,” he said. At the risk of being accused of being influenced by politically incorrect, somewhat misogynistic stereotypes beloved by British comedians in the 1970s, I could not help but smile when he said, in all seriousness, that he had interpreted that evil presence as being his mother-in-law.

On closer consideration, though, this turned out to be a lovely example of an interpretation based on the interaction between culture and physiology. As the driver clarified, he had been convinced that the strong malign presence, staring at him with evil intent, was not actually his mother-in-law at the time the incident occurred—she was his mother-in-law-to-be. When the episode had taken place, he was lying in bed next to his future wife—in her parents’ bed, having taken advantage of the fact that his future in-laws were away on holiday. Furthermore, he was a Cypriot and, within his extended family, premarital sex was definitely frowned upon. So when he woke up in the early hours, unable to move and terrified, even though he could not turn over to look in the direction of the presence, he was convinced it was his very angry future mother-in-law.

Is Sleep Paralysis Always Harmless?

I am keen to spread the message far and wide that sleep paralysis, although it can be absolutely terrifying, is generally harmless. That is not to minimize the very real stress that can be caused when sufferers are unaware of the true nature of the phenomenon and either believe that they are losing their minds or are on the receiving end of bizarre supernatural attacks. In my experience, simply discovering that there is a third possible explanation, one that is scientifically and medically recognized, provides huge relief to sufferers. Sometimes that knowledge alone can be enough to reduce sleep-related anxiety, resulting in more regular sleep patterns, which in turn may reduce the frequency of sleep paralysis episodes. I am therefore somewhat hesitant to point out that it has been argued that, in certain very rare and specific circumstances, sleep paralysis may result in death.

This possibility was put forward by Shelley Adler as an explanation of the phenomenon of sudden unexpected nocturnal death syndrome (SUNDS).41 Between the late 1970s and early 1990s in the United States, over 100 Southeast Asians died in their sleep without any obvious cause. The deaths occurred predominantly among male Hmong refugees, usually within two years of arriving in the country. Several possible causes were investigated, including toxicology, genetics, metabolism, and nutrition, but none of these investigations provided a solution to the mystery. It was found that the victims appeared to have some abnormalities of the cardiac conduction system, but this did not explain why the deaths only occurred following arrival in the United States.

Adler argued that the explanation may involve the conjunction of a number of very specific factors, one of which was sleep paralysis. The Hmong believe that one is at risk of spiritual attack from dab tsog (pronounced “da cho”) during sleep. Dab tsog is a traditional nocturnal pressing spirit, and hence such attacks take the form of sleep paralysis episodes. Whereas one might survive one or two such attacks, repeated attacks were thought to weaken and ultimately kill the victim. Back in their countries of origin, the Hmong would have traditional remedies to deal with such attacks. They would consult the local shaman and engage in various rituals, including animal sacrifice, to ward off the evil spirits. They also believed that ancestor spirits would protect them from evil spirits so long as religious practices had been properly followed. Their belief in the effectiveness of the rituals would be likely to reduce their anxiety, improving the quality of their sleep, and ultimately having the desired effect.

As refugees in the United States, however, these traditional remedies were no longer available. Also, it appeared that whereas the protective ancestral spirits had been unable to relocate, the dab tsog had somehow managed to follow the refugees to their new homes. Other factors also came into play to explain why it was particularly the male heads of households who were prone to SUNDS. Back in their home countries, society was organized in a patriarchal manner, and spiritual protection of the family was one of the responsibilities of the male head of the household. In the context of a new unfamiliar society, the older Hmong men found themselves unable to fulfill their traditional roles. Typically, they were unemployed and struggled to learn English, whereas their children learned to adapt much more quickly. The stress that this situation caused would disturb sleep, making sleep paralysis episodes more likely. Ultimately, according to Adler, it was this deadly combination of a culture-specific belief system, a stressful new context, an underlying cardiac abnormality, and susceptibility to sleep paralysis that resulted in SUNDS.

I cannot emphasize too strongly that, even if Adler is correct in her explanation of SUNDS, in the vast majority of cases, sleep paralysis episodes are essentially harmless, albeit potentially terrifying. It was the tragic and unlikely combination of factors described above that may have had deadly consequences for specific Hmong refugees, factors that, I sincerely hope, will not apply to any readers of this book.

Sleep Paralysis as Artistic Inspiration

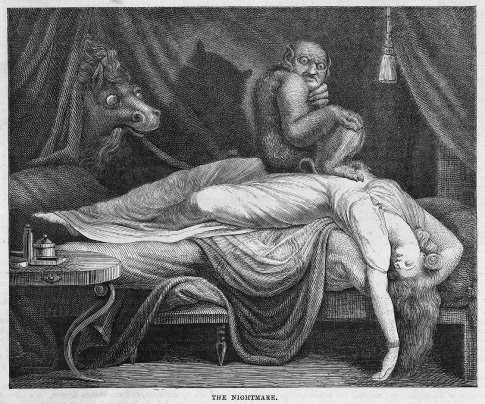

It is not surprising that artists of all kinds have been inspired by episodes of sleep paralysis, given the vivid and nightmarish imagery that is so often a feature of the phenomenon. Without doubt, the most famous painting representing sleep paralysis is The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli (figure 2.2). Painted in 1781, it was enormously popular with the public, inspiring Fuseli to produce at least three other versions of the same scene. The painting presents a sleeping woman, reclining in a supine position with her head and arms dangling over the edge of the bed. A grotesque demon is perched on her chest, his full weight pressing down on her. In the background, a weird horse stares at the scene through eyes that lack pupils. The scene successfully conjures up the frightening and oppressive atmosphere of a nightmare. Interestingly, those who are susceptible to sleep paralysis are more likely to actually experience an episode if they sleep on their backs (although it might be felt that sleeping in the rather extreme position depicted on this canvas is simply asking for trouble).

Figure 2.2

Henry Fuseli’s painting The Nightmare, the first version of which was painted in 1781, memorably captures many aspects of sleep paralysis, including the nightmarish imagery, the sense of being watched, and pressure on the chest.

Fuseli is far from the only artist to produce visual representations of sleep paralysis. Type “sleep paralysis images” into your favorite search engine and an almost endless array of terrifying depictions will appear. The work of photographer Nicolas Bruno is particularly striking.42 His surreal compositions, reminiscent of the works of René Magritte, are beautiful, disturbing, and fascinating in equal measure and are clearly directly inspired by his own experiences of sleep paralysis. They illustrate many of the main features of the phenomenon, including the sense of unreality, impending threat, immobility, and struggling for breath.

Inevitably, filmmakers have also been drawn toward this topic. The documentary films of Carla MacKinnon and Rodney Ascher have already been mentioned, but sleep paralysis has also inspired dozens of fictional horror movies and TV shows, including The Conjuring, Dead Awake, Between the Darkness, The Haunting of Mia Moss, Shadow People, Mara, and Slumber, not to mention, of course, The X-Files. Wes Craven’s hugely successful 1984 horror film, A Nightmare on Elm Street, is said to be directly inspired by press reports at that time reporting on SUNDS. Ironically, as Corinne Purtill wrote in an article for Quartz News, sleep paralysis episodes featuring a threatening “man in a hat” are now common around the world, possibly yet another example of a fictional creation—in this case, the notorious killer, Freddy Krueger—making his way from a writer’s imagination into our own nightmares!43

Arguably one of the most bizarre manifestations of sleep paralysis—in a very strong field—was that which occurred to a woman in Moscow in 2016, as described by Matthew Tompkins.44 The woman had been playing Pokémon Go on her smartphone prior to drifting off to sleep. Later, she woke to find herself being sexually assaulted by an actual Pokémon character. Struggling against the pressure holding her down but unable to scream to rouse her boyfriend, who was sleeping beside her, she was eventually able to get up. The Pokémon had gone and was nowhere to be found. She called the Moscow police to report the attack.

Many famous literary works have included descriptions of sleep paralysis, including Herbert Melville’s 1851 classic Moby-Dick, Thomas Hardy’s (1888) story The Withered Arm, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s (1922) novel The Beautiful and Damned, and Ernest Hemingway’s (1938) short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” Here is one literary example, a short extract from Guy de Maupassant’s (1887) story Le Horla:

I sleep—a long time—2 or 3 hours perhaps—then a dream—no—a nightmare lays hold of me. I feel that I am in bed and asleep—I feel it and I know it—and I feel also that somebody is coming close to me, is looking at me, touching me, is getting on to my bed, is kneeling on my chest, is taking my neck between his hands and squeezing it—squeezing it with all his might in order to strangle me.

And then suddenly I wake up, shaken and bathed in perspiration; I light a candle and find that I am alone, and after that crisis, which occurs every night, I at length fall asleep and slumber tranquilly until morning.45

There can be little doubt that Maupassant was all too familiar with the terror that comes in the night.

Prevention and Coping Strategies

Most people will never experience an episode of sleep paralysis. Of those who do, most will only experience the mild form, that is, a period of paralysis lasting a few seconds that spontaneously lifts. Such episodes may cause some consternation but are easily shrugged off and forgotten. A smaller percentage may experience the more florid form of sleep paralysis involving such symptoms as a strong sense of malign presence, hallucinations, difficulty breathing, and intense fear. Not surprisingly, these episodes may cause considerable stress and anxiety in the short term, but most people who experience them will probably only experience them once or twice in their lifetime. If so, they may always be remembered but are unlikely to seriously affect quality of life in the long term. Finally, there is a very small percentage of the population who suffer from what Brian Sharpless refers to as recurrent fearful isolated sleep paralysis. These poor unfortunates may experience the florid form of sleep paralysis on a regular, possibly nightly, basis. There is a strong chance that their quality of life will be seriously impaired by their nocturnal terrors. What, if anything, can be done to help them?

The sad truth is that there has been little systematic research into the best strategies to reduce or eliminate the frequency of sleep paralysis episodes or to cope with them when they do occur. Some general advice can be offered on the basis of previous research findings. Furthermore, numerous websites provide anecdotal accounts of different strategies that people have found to be effective. One of the very few studies to attempt any analysis of the self-reported effectiveness of these strategies was carried out by Brian Sharpless and Jessica Grom.46 They collected data using clinical interviews from 156 undergraduate students who had experienced isolated sleep paralysis. Around three-quarters of the sample reported that they experienced fear during the episodes, with around 15 percent reporting clinically significant distress. About 20 percent reported that they had made attempts to prevent the attacks, and about 80 percent of these claimed some success. This relatively low percentage of respondents who actively sought to prevent the episodes probably reflects the fact that for most respondents the episodes were not frequent. A much larger proportion, around 70 percent, actively attempted to disrupt the episodes when they did occur, but their self-reported success rate was only 54 percent.

It is well established that an irregular sleep pattern makes sleep paralysis episodes more likely in those with the underlying susceptibility, so practicing good sleep hygiene is recommended. In addition to adopting a regular sleep pattern that is appropriate with respect to age, lifestyle, and health, here are some more general tips about sleep hygiene from the National Sleep Foundation:47

- • Limit daytime naps to thirty minutes.

- • Avoid stimulants such as caffeine and nicotine close to bedtime.

- • Exercise to promote good-quality sleep.

- • Steer clear of food that can be disruptive right before sleep.

- • Ensuring adequate exposure to natural light.

- • Establish a regular relaxing bedtime routine.

- • Make sure the sleep environment is pleasant.

As noted, stress, anxiety, and depression are all known to have an adverse effect on sleep quality, and so sufferers from such conditions may well find that any treatment that is effective in improving their mental health also has the indirect effect of reducing the frequency of sleep paralysis episodes. For example, in one study it was found that five of eleven patients suffering from panic disorder and recurrent isolated sleep paralysis showed improvements in the latter even though only the former had been directly treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy.48 For those with strong beliefs that the episodes really are some sort of spiritual attack, traditional remedies may well be successful. This is not to endorse such interpretations but simply to recognize that belief in such remedies may well be strong enough to reduce anxiety, thus improving sleep quality and thereby reducing the frequency of attacks. To date, there are no psychopharmacological treatments for isolated sleep paralysis with proven track records, although anecdotal evidence and case histories suggest that some antidepressants may have potential as treatments.

In addition, those prone to sleep paralysis should avoid sleeping on their backs, as it is known that more episodes occur in this sleep position than any other. In extreme cases, some sufferers try sleeping sitting up or sew walnuts or tennis balls into the back of their pajamas so that the supine position is too uncomfortable to adopt.

Sufferers are generally more likely to adopt strategies to cope with sleep paralysis episodes when they do occur rather than trying to prevent them. The most commonly reported technique is to attempt, by a huge effort of will, to move a finger or a toe. If successful, this will break the spell. It is also commonly reported that the sufferer may attempt to scream at the top of their lungs. However, the only observable result is typically a feeble croak or groan. Sometimes, however, the sufferer’s partner is able to recognize these telltale signs and rouse the sleeper, thus rescuing them from their torment.

Some sufferers learn to recognize that they are having a sleep paralysis attack while the attack itself is occurring and attempt mental relaxation techniques, with varying levels of success. Others go a step further and, on recognizing that they are experiencing sleep paralysis, make no effort at all to disrupt the experience but instead simply let it happen and enjoy the experience in the same way that some people enjoy a good horror movie. This does not work for everyone. Some who try it report that, despite the fact that they are fully aware that what they are experiencing is not real, there is nothing they can do to control the overwhelming terror that grips them.

Brian Sharpless and Karl Doghramji have produced A Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Manual for Recurrent Isolated Sleep Paralysis: CBT-ISP, which is included as an appendix in their book Sleep Paralysis: Historical, Psychological, and Medical Perspectives. This is the most comprehensive, systematic treatment program for the condition currently available, covering such topics as self-monitoring, psychoeducation, sleep hygiene, disruption techniques, and coping with catastrophic thoughts and hallucinations. Although, at the time of writing, no outcome studies had yet assessed the success rate of this program, it does appear to provide a promising first step in the right direction.49 If you suffer from frightening sleep paralysis episodes, I wish you well in finding strategies to reduce their frequency or even eliminate them—or, failing that, at least learning to live with them.