3

High Spirits, Part 1: Ghostly Encounters

Belief in ghosts is common in societies throughout history, and yet conventional scientists continue to reject any notion that some essence of a person—the spirit, soul, or consciousness, call it what you will—survives bodily death. If ghosts do not exist, what alternative explanations might there be for such widespread belief and for the fact that, as we saw in chapter 1, a sizable minority of even modern Western societies claim to have had personal encounters with ghosts? Sleep paralysis provides a plausible explanation for many such cases, as described in the previous chapter. In this chapter, we will consider a range of other factors that might lead someone to believe that they have had an encounter with a spirit from beyond the grave.

If ghosts really are the spirits of the dead, this would have profound implications for our understanding of the nature of consciousness. Indeed, any evidence that supported the reality of some form of life after death would necessarily imply that dualism was the correct philosophical view of consciousness. Dualists follow the great French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes in maintaining that the universe consists of two fundamentally different kinds of stuff: the physical and the mental. Physical objects, such as chairs, cakes, and brains, have properties like mass, location, and size, whereas the mental realm does not. Thoughts, dreams, and desires cannot be located in space and measured in the same way that physical objects can.

Dualism is an appealing notion for many people, as it seems to be consistent with human experience. Our mental life does indeed intuitively feel altogether different from the processes that affect the atoms and molecules that make up the universe “out there.” The problem is that no one has managed to come up with a plausible explanation of how an immaterial soul could interact with a material brain. In attempting to solve this problem, some philosophers of mind have considered the possibility that there are not, in fact, two fundamentally different kinds of stuff in the universe: there is just one. Such monist views take one of two forms: either everything is mind or everything is matter. Without going into details, suffice it to say that, to date, the nature of consciousness has not been adequately explained by either philosophers or scientists, although real progress has been made in recent decades.1

According to the vast majority of modern neuroscientists, however, consciousness is entirely dependent on the activity of neurons in a living brain and cannot be separated from that underlying neural substrate. This view is supported by a huge amount of evidence, including consideration of the effects of drugs, brain damage, and direct electrical and magnetic stimulation of the brain, as well as data from recordings of brain activity. Although it would be premature to claim that modern neuroscience can provide a comprehensive explanation of the nature of consciousness, very little evidence appears to support a dualist view—but convincing evidence of post mortem survival clearly would do so (as would some interpretations of out-of-body experiences, as discussed in chapter 7).

There are many reasons to doubt the traditional interpretation of ghosts and hauntings, as this chapter will demonstrate. First and foremost, almost all of the evidence put forward in support of the existence of ghosts is anecdotal in nature. Such hearsay evidence should be treated with caution for reasons outlined by Scottish philosopher David Hume in a famous essay titled “Of Miracles” published in 1748.2 Hume addressed the question of whether one would ever be rationally justified, in the absence of any other evidence, to accept another person’s claim that they had witnessed a miracle. He defined a miracle as an event that violates a law of nature, thus including paranormal events. He then argued that “no testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle unless that testimony be of such a kind that its falsehood would be more miraculous than the fact which it endeavours to establish.”3 He further argued essentially that, whereas evidence for the violation of laws of nature is thin on the ground and possibly even nonexistent, evidence that people sometimes lie and make mistakes is plentiful. Therefore, in practice it is always more reasonable to doubt reports of miracles than to accept them.

It is also worth noting that the reported appearance and behavior of ghosts vary considerably from one society to another as discussed by historian R. C. Finucane.4 Consider his description of ghosts in ancient Greece:

In Homer’s day, ghosts deserting the mangled remains of warriors on the plains of Troy flitted and squeaked like crazed bats all the way down to Hades, where they spent eternity meekly standing around murmuring to each other in hollow tones. Their rather boring conversation ran to gossip concerning recent arrivals, arguments over family pedigrees, and long-winded recitations about famous battles.

Clearly, ghosts in ancient Greece were rather different from those reported in the modern era. As Finucane shows, ghosts from various other eras, such as the early Christian era, the Reformation, and the Victorian era, all had their own characteristic appearance and behavior. Such variation across cultures is best explained by the idea that ghosts are the products of particular belief systems that dominated at particular times and places as opposed to having any objective reality.

For modern Western readers, I suspect that the word ghost conjures up a mental picture of a transparent apparition, perhaps having just walked through a wall (figure 3.1).5 Such depictions are common in works of fiction. In fact, however, reports of ghostly encounters of this kind are relatively rare. It is far more common for people to believe that a ghost is around on the basis of far less dramatic evidence, including such things as a sense of presence, shivers down the spine, sudden drops in temperature, dizziness, and so on, as well as inexplicable smells, noises, or the movement of objects.

Hoaxes

Might it be the case that all reports of ghostly encounters are simply hoaxes, the accounts coming from either the victims or the perpetrators of such hoaxes? This is extremely unlikely, but it should always be borne in mind that deliberate deception is indeed the correct explanation for some cases, albeit probably only a minority.

Figure 3.1

For most Westerners the word ghost conjures up an image of a full-form apparition as in this illustration—but most claims of ghostly encounters are based on much less dramatic sensations.

It is appropriate in this context to outline three possible explanations for so-called poltergeist activity (figure 3.2). The word poltergeist can be literally translated as noisy spirit, corresponding to the traditional interpretation of such reports as being due to the activity of a destructive ghost. Poltergeists are said to engage in a wide range of disturbing behavior, including making loud noises, levitating (and often smashing) objects, starting fires, causing flooding, and interfering with electrical equipment. In some cases, it is claimed that poltergeists may directly attack people.

Although some parapsychologists accept the traditional notion that poltergeist activity is caused by the spirit of a person who has died, others reject this account in favor of an alternative paranormal interpretation. It has often been noted that the disruptive activity typically only occurs around one specific individual, whom parapsychologists refer to as the focus of the activity. This individual is often someone who was experiencing severe mental health problems prior to the outbreak of poltergeist activity. The idea is that this inner psychological turmoil somehow becomes externalized in the form of psychokinetic energy, leading to the effects described. So, according to this view, although the disruption is a genuine paranormal effect, it is caused by the troubled mind of a living person rather than the spirit of a dead person.

Boring old skeptics like me agree that in such cases the cause of the disruption is a living person. They disagree, however, with the idea that anything paranormal is involved. Instead, they view such disruption as deliberate attention-seeking behavior on the part of the focus person—in other words, a hoax. It would be going too far to claim that all alleged poltergeist cases have been proven to be hoaxes. All too often, skeptics are not actually welcomed to investigate with a view to discovering possible nonparanormal explanations as a “genuine” ghost story is considered to be much more interesting than the exposure of a hoax. However, dozens of such cases can satisfactorily be accounted for as hoaxes. We will limit ourselves here to describing a couple of famous cases.6

Figure 3.2

An 1851 illustration of alleged poltergeist activity in the presbytery in Cideville, France.

The first is the case of the Columbus Poltergeist, which received international attention in 1984. The family of Tina Resch reported that objects had started flying around in their home shortly after fourteen-year-old Tina, an emotionally disturbed adoptee, had seen the movie Poltergeist. The Columbus Dispatch sent reporter Mike Harden to interview Tina, and he took photographer Fred Shannon along in the hope that they might catch some paranormal activity on camera. The resulting article included several dramatic photographs allegedly showing precisely that. One famous image shows Tina sitting in an armchair as a telephone flies through the air in front of her. She is apparently screaming in terror as this happens. Parapsychologist William Roll stayed in the Resch house to investigate the case and concluded that genuine recurrent spontaneous psychokinesis was occurring. However, he himself never actually saw any objects fly through the air.

Not everyone was convinced. James Randi went to Columbus to investigate for himself but was denied access to the house. By examining the photographs taken by Fred Shannon, Randi was able to present a strong case that the phenomena were faked by Tina herself.7 Shannon had reported that no objects ever took off if he was observing them directly. So he had obtained his shots by looking away, holding his camera pointing in what he hoped would be the right direction, and pressing the shutter when he detected movement in the corner of his eye. The resulting photographs were, according to Randi, all consistent with the idea that Tina had simply waited until no one was watching her and then thrown the objects, pretending to be shocked and terrified as they flew through the air.

As Randi goes on to describe, even stronger evidence of fakery was to emerge, albeit by accident. The case had become something of a media circus, with reporters and TV film crews coming from far and wide to get in on the action. On one such occasion, a crew from WTVN-TV in Cincinnati had been packing up their kit after filming, but the cameraman had inadvertently left his camera running. The recording clearly shows Tina looking around. Thinking she was unobserved, she pulls a table lamp toward herself, screaming with feigned terror. When confronted with this undeniable evidence, Tina claimed that she had only been fooling around because, on this occasion, she wanted the cameraman to leave.

There is a tragic postscript to this story. Clearly, Tina did not have a happy life. It is reported that John and Joan Resch were physically abusive toward their adopted daughter, Tina. Following her time in the media spotlight, Tina subsequently married and divorced twice. She changed her name to Christina Boyer. In 1992, her three-year-old daughter, Amber, was beaten to death. Christina and her boyfriend were tried for her murder. She was sentenced to life plus twenty years.

An even more famous case is that of the Amityville Horror, which became the subject of an internationally bestselling book written by Jay Anson and published in 1977, The Amityville Horror: A True Story. The book allegedly describes a series of terrifying paranormal events that beset the Lutz family after they moved into 112 Ocean Avenue in Amityville in December 1975. Within a month, George and Kathy Lutz and their three children had fled the property in terror. The book was the basis for a series of films, the first of which was released in 1979.

The house certainly had a horrific past prior to being bought by the Lutzes. It was there that, in November 1974, Ronald DeFeo Jr. had shot dead six members of his own family. He subsequently claimed that he had heard voices telling him what to do. A year later, he was sentenced to six consecutive life terms, despite his plea of insanity.8 Shortly after that, the Lutz family took up residence at 112 Ocean Avenue. Knowing the house’s tragic history, the Lutzes took the precaution of calling in a family friend, referred to as Father Frank Mancuso in the book (real name, Father Ralph J. Pecararo) to bless the house. The priest claimed he heard a masculine voice demanding that he “Get out!” as he performed the ritual.

The series of bizarre events that allegedly took place in the short time that the Lutzes were in the house is summarized by Robert Morris, in his review of the book, as follows:

Some were physical: a heavy door was ripped open, dangling on one hinge; hundreds of flies infested a room in the middle of winter; the telephone mysteriously malfunctioned, especially during calls between the Lutzes and Mancuso; a four-foot lion statue moved about the house; windows and doors were thrown open, panes broken, window locks bent out of shape; Mrs. Lutz levitated while sleeping and acquired marks and sores on her body; mysterious green slime oozed from the ceiling in a hallway; and so on. Some phenomena were experiential: Mrs. Lutz felt the embrace and fondling of unseen entities; Mr. Lutz felt a constant chill despite high thermostat temperatures; the Lutzes’ daughter acquired a piglike playmate; the Lutzes saw apparitions of a pig and a demonic figure; the children misbehaved excessively and the family dog slept a lot and avoided certain rooms; marching music was heard; et cetera.9

Despite Anson’s assurance that “all facts and events, as far as we have been able to verify them, are strictly accurate,” the evidence strongly suggests that this case is nothing more than a deliberate hoax. According to Morris, Anson made very little attempt to verify any of the Lutzes’ claims. He appears to have never once visited the property himself nor to have directly interviewed the main witnesses, instead basing his account mainly on tape-recorded accounts from the Lutzes.

Morris discusses a number of factors that should lead us to be dubious regarding the accuracy of Anson’s account, all of which apply to assessing accounts of anecdotal evidence for paranormal claims in general, as discussed in the following sections on the psychology of hauntings. In the present context, the important point is that there is also clear evidence that much of the account is pure fabrication on the part of the Lutzes. There are several examples of the Lutzes giving descriptions of the weather on specific dates that clearly do not match the actual weather on those dates. For example, they claim that a torrential rainstorm on January 13 prevented them from leaving the house, forcing them to spend another night there. Records show that no such storm took place. Furthermore, William Weber, the lawyer who defended Ronald DeFeo Jr. at his trial, is on record as saying, “I know this book is a hoax. We created this horror story over many bottles of wine.”10 In this case, the motive was not attention-seeking behavior, it was simple greed. It is worth noting that no subsequent owners of the property reported any paranormal activity.

Perhaps it is time to introduce French’s First Law: “The more spectacular the claim of any kind of ghostly encounter, the more likely it is to be based on a deliberate hoax.”

Misinterpreting Natural Phenomena

Although the possibility of deliberate hoaxing should always be borne in mind when assessing claims of ghostly encounters, especially the more sensational ones, it is almost certainly the case that most such claims are not attempts at deliberate deception. A number of potentially relevant psychological factors may underlie such claims.11

An individual may become convinced that their house is haunted is because they have had one or more experiences that they simply cannot explain any other way. Of course, just because one cannot explain something does not mean that there is no naturalistic, nonparanormal explanation—but, equally, for someone who already believes in ghosts, it is not completely irrational to speculate about the possibility of a paranormal explanation.

The allegedly inexplicable experience in question may be purely psychological in nature, such as a frightening episode of sleep paralysis as described in the previous chapter. However, sometimes the puzzling experiences may be related to events in the external physical world. Vic Tandy and Tony Lawrence list a number of obscure yet mundane phenomena that might produce unexpected physical effects that could lead someone to suspect that their home was haunted: “water hammer in pipes and radiators (noises), electrical faults (fires, phone calls, video problems), structural faults (draughts, cold spots, damp spots, noises), seismic activity (object movement/destruction, noises), . . . and exotic organic phenomena (rats scratching, beetles ticking).”12

A rather cute example of the mysterious movement of objects was reported in the British media in March 2019.13 Stephen Mckears, a seventy-two-year-old man from Severn Beach, South Gloucestershire, was puzzled when he noticed that his garden shed was being tidied up overnight by unknown means and began to consider the possibility that a helpful ghost was responsible—a kind of anti-poltergeist who did the opposite of more traditional poltergeists by creating order out of chaos. After some months, and with the help of a friendly neighbor, Stephen decided to get to the bottom of the mystery by setting up a video camera to record what was happening when he left his shed. The answer came as something of a surprise—no ghost, but a tiny house-proud mouse spending several hours tidying away the metal objects that Stephen had deliberately left scattered around. These included not only nuts, bolts, and screws but even small metal tools that the determined mouse would strenuously tidy away. This is a wonderful example of an explanation for the mysterious movement of objects that no one would have guessed if we did not have the evidence of the video recording, reminiscent of that scene from Disney’s Cinderella. Needless to say, the video went viral, enthralling viewers around the world.

Of course, if one is able to figure out the cause of the initially puzzling events, one may be able to stop worrying about them (although this often does not apply in cases of sleep paralysis). But if one is unable to come up with a satisfactory nonparanormal explanation, the idea that one’s house is haunted may take hold, and thenceforth even relatively mundane events are interpreted within that context. You can’t find your keys in the morning? Aha, the ghost must have moved them! Your TV malfunctions? Damn it, that ghost is causing problems again! I know from experience that if a light begins to flicker when I am giving a talk on ghosts, I am guaranteed to elicit a nervous giggle from my audience if I suddenly look puzzled and mutter, “Oooh, spooky!” Doing the same thing during a statistics lecture would not elicit the same response. Context is all-important.

Context and Prior Belief

Indeed, I would go so far as to argue that the two most important psychological factors associated with reports of ghostly encounters are context and prior belief in ghosts. At the anecdotal level, many readers will be familiar with the effects of being told, prior to entering an old building such as a stately home, castle, or pub, “This place is said to be haunted.” Almost at once, one is more alert to stimuli that one would probably not notice unless so primed. These stimuli may be external, such as creaking floorboards or cold drafts, or internal, such as a chill down the spine or the feeling that you are being watched.

Rense Lange and James Houran demonstrated this effect empirically.14 They asked two groups of participants to walk around a disused movie theater and to note whether they experienced any cognitive, physiological, emotional, psychic, and/or spiritual responses in reaction to their surroundings. Half of the participants were simply told that the property was currently being renovated, and the other half were told that paranormal activity had been reported there. As predicted, the latter participants reported significantly more physical, emotional, psychic, and spiritual experiences than those in the former group.

In a somewhat similar study, Richard Wiseman and colleagues demonstrated the role played by prior belief in ghosts.15 They collected data from 678 participants walking around Hampton Court Palace, reported to be one of the most haunted locations in England. It is alleged that the ghost of Catherine Howard still lingers in this historic building. Catherine, the fifth wife of Henry VIII, was found guilty of adultery and sentenced to death fifteen months after her marriage to Henry in 1540. It is said that on hearing the news of her sentence, she tried to run to Henry to beg for her life, but guards blocked her way and dragged her, kicking and screaming, back along a part of the palace now known as “The Haunted Gallery.” Since then, it is claimed that inexplicable screams are sometimes heard in this area and a mysterious woman in white sometimes appears. A range of other anomalous experiences are reported in this and other areas in the palace, including dizziness, a strong sense of presence, and sudden cold spots. In Richard’s study, as predicted, those visitors who believed in ghosts reported more unusual experiences as they walked around than did nonbelievers, and they were also more likely to attribute these experiences to ghostly intervention.

On Seeing Things That Are Not Really There

One of the responses from skeptics to claims of ghostly encounters that causes the most anger and annoyance to claimants is, “Maybe you were just seeing things.” What is clearly implied but not explicitly stated here is that maybe you were seeing things that were not really there. The reason that this suggestion causes such a defensive reaction is that, for most people, suggesting that they may have been hallucinating is akin to suggesting that they are “crazy.” In fact, hallucinations occur far more frequently among the nonclinical population than is generally realized.16 The previous chapter dealt with one particular type of hallucinatory experience—sleep paralysis—but hallucinations can occur in other contexts without necessarily being an indication of serious psychopathology. Furthermore, hallucinations may occur in all sensory modalities, not just “seeing things.”

In recent years, views of mental illness have moved away from seeing psychosis as an all-or-none phenomenon to instead accepting that psychotic symptoms, including the tendency to hallucinate, lie on a continuum. Some people never experience a single symptom in their lives. Others experience such symptoms frequently and, in some cases, may find them distressing enough to require professional help from a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist. But many others are between these two extremes and may experience occasional psychotic symptoms without ever meeting the criteria for clinical psychosis. Indeed, some people even come to view such symptoms as a positive aspect of their lives.17

Hallucinations are not the only way we may perceive things that are not really there. Robert Todd Carroll defines the phenomenon of pareidolia as “a type of illusion or misperception involving a vague or obscure stimulus being perceived as something clear and distinct.”18 Thus, for example, we often see faces and forms in random visual stimuli such as in clouds, the grain of wood, or stains on a floor. Leonardo da Vinci offered the following advice to his followers as a method to facilitate the development of their imaginations and artistic expression:

If you look at walls covered with many stains or made of stones of different colours, with the idea of imagining some scene, you will see in it a similarity to landscapes adorned with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, broad valleys, and hills of all kinds. You may also see in it battles and figures with lively gestures and strange faces and costumes and an infinity of things.19

One of the most commonly perceived categories as a result of pareidolia is faces. This is perhaps not surprising when one considers just how important faces are as a source of information in our day-to-day interactions. From an evolutionary perspective, it was vitally important that an individual could quickly recognize if another human being was a stranger or someone they knew. Were they a threat or not? What was their current emotional state and likely intentions? What were they likely to do next? Our brains have evolved to allow us to quickly decide whether we recognize someone and, if we do, to identify them and what we know about them, as well as their current emotional state. Different parts of our brains are involved in these different components of face recognition. Research using the noninvasive neuroimaging techniques of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG)20 suggests that illusory faces are processed in the brain in the same way that real faces are for the first quarter of a second of processing but are then processed as ordinary objects rather than faces.21 This is consistent with the idea that our cognitive systems are wired to rapidly detect anything that looks like it may be a face even if it is then quickly determined that it is not. It is not the case, therefore, that pareidolia is the product of slower cognitive reinterpretation of stimuli.

For most of us, spotting faces in inanimate objects in the world around us is simply a source of mild amusement, but sometimes such perceptions are deemed to have greater significance.22 It is notable that images of religious figures, such as Jesus and the Virgin Mary, crop up rather a lot. For example, as reported by Wikipedia, images of Jesus “have been reported in such varied media as cloud photos, Marmite, chapatis, shadows, Cheetos, tortillas, trees, dental x-rays, cooking utensils, windows, rocks and stones, painted and plastered walls, and dogs’ hindquarters.”23 True believers are especially likely to be conclude that such images are divinely produced (with the possible exception of the last example listed).

It seems reasonable to suggest that pareidolia may well be responsible for some alleged ghost sightings, given the general human tendency to perceive meaningful forms and figures in ambiguous and degraded visual input. There is evidence supporting the idea that believers in the paranormal may be more susceptible to pareidolia than nonbelievers. Peter Brugger and colleagues presented brief displays of random dot patterns to volunteers.24 The volunteers were asked to indicate any trial where they saw “something meaningful,” having been informed that the experiment was an investigation of subliminal perception and that “meaningful information” was embedded in the images on some trials. In fact, all of the displays consisted entirely of random dot patterns. Believers in the paranormal reported seeing something meaningful on significantly more trials than did skeptics.

Considering the specific tendency to see faces that are not really there, as opposed to a general tendency to see “something meaningful,” it has also been found that believers in the paranormal are more prone to illusory face perception when presented with images of landscapes and scenery, some of which did contain face-like areas and some of which did not.25 Believers were better at spotting the face-like areas when they were there but also more likely to report seeing them when they were not there; in other words, they demonstrated a response bias toward positive responses. Interestingly, the same pattern was found when participants were divided into groups on the basis of their religious beliefs, but it should be noted that paranormal and religious belief were strongly correlated in this study.

On Not Seeing Things That Are There

In the context of providing potential explanations for ghostly encounters, the possibility of claimants seeing things that are not really there has, perhaps understandably, received rather more attention than the opposite: that is, the failure to see things that really are there. However, this is a topic that has been the subject of a considerable amount of psychological research more generally in recent years. Psychologists refer to this failure to notice stimuli that are right before our very eyes when we are engaged in some other task as inattentional blindness.

The most famous study of inattentional blindness was reported by Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris in 1999.26 Participants were asked to watch a short video clip in which two groups of people, one wearing white shirts, the other wearing black shirts, throw a ball to each other. They were instructed to count the number of times that the people in the white shirts threw the ball to each other, ignoring the people in the black shirts. At the end of this simple task, the volunteers gave their answer to the question posed and were then asked if they had noticed anything unusual as they watched the video. In fact, halfway through the video, someone dressed in a gorilla suit had walked into the center of the action and stood there beating their chest for several seconds before walking out of shot. Surprisingly, around half of the participants in this study completely failed to spot the gorilla. This is a highly counterintuitive result, as most people are convinced, prior to hearing about this experiment, that something so odd and unexpected would be sure to grab their attention.

This reminds me of an incident from my personal life that occurred many years ago when my wife, Anne Richards, and I were looking to move house. We had called in at an estate agent in Blackheath, London, and Anne was busily concentrating on learning more about the available properties in the area. I must confess that I was paying rather less attention to this important task than she was. When we emerged back on the street, I said to her, “That was a bit weird. I wondered if maybe we were taking part in a psychology experiment.” Looking puzzled, she replied, “What do you mean?” “Didn’t you notice anything a bit odd in there?” I asked. She hadn’t. I instructed her to pretend to be looking at the details of properties on display in the window but to actually look through into the office that we had just spent half an hour in. She did so and was surprised to see—I kid you not—a full-size stuffed bison in the middle of the room. Concentrating on the important task of considering possible new properties, she had completely failed to spot this large and totally incongruent object.

The importance of inattentional blindness was recognized immediately by psychologists. After all, many serious accidents occur because people fail to notice stimuli that are right in front of them. Literally hundreds of experiments have now been carried out to learn more about the phenomenon, and, indeed, it became a focus of Anne’s research in the Department of Psychology at Birkbeck College, University of London. She assures me that her interest in this topic is totally unrelated to her inability to spot stuffed bisons in estate agents’ offices!

Some years later, Anne called to ask me if I had a copy of a scale to measure the personality variable known as absorption. If you are the kind of person who would get a high score on such a measure, then you are the kind of person who, when reading a novel, watching a film, or doing a crossword puzzle, would be very difficult to distract from that activity; that is to say, you would become absorbed in whatever you were focusing your attention on. Although the general view among inattentional blindness researchers at the time was that susceptibility to this phenomenon did not correlate with any particular personality variables, we both felt it was likely to correlate with absorption. Furthermore, I was intrigued because I knew from my wider reading that absorption reliably correlated with paranormal belief and the tendency to report paranormal experiences.

The obvious next step was to carry out a study to investigate the relationship, if any, between all three of these variables.27 We did not use the gorilla video in our study but instead used a conceptually similar task. Volunteers were instructed to watch a computer screen displaying black and white letters moving around the screen and sometimes “bouncing” off the edge of the screen. They were asked to count the number of times the white letters bounced off the edge of the screen while ignoring the black letters. Halfway through, a red cross moved slowly across the screen from one side to the other. At the end of the task, participants reported how many times the white letters had bounced off the edge of the screen and were then also asked if they had noticed anything unusual during the task. As expected, around half of the participants did not see the red cross. These inattentionally blind participants had significantly higher scores on both a measure of absorption and on a measure of paranormal belief and experience, results that we replicated in a second experiment.

How might inattentional blindness relate to reports of ostensibly paranormal events? One possibility is that some reports of allegedly ghostly encounters (but by no means all) may have a mundane nonparanormal explanation that had been missed by the claimant because they failed to take in some relevant information at the time. As a hypothetical example, suppose someone were to claim that a book moved from one location to another when no one else was in the vicinity. If one were to suggest that maybe there was someone else around who may have moved the book and that they just did not notice the other person, they would probably indignantly insist that they were absolutely sure that they would notice if anyone else was nearby. But would they? After all, lots of people fail to see a gorilla beating its chest when it is right in front of them.

Although the term inattentional blindness did not appear in print until the late 1990s, the phenomenon had in fact been inadvertently demonstrated almost four decades earlier in a couple of quirky studies by parapsychologist Tony Cornell.28 Cornell appeared to accept the idea that spirits of the dead really do sometimes appear to the living. He wanted to study how people react to such appearances. To do so, he covered himself from head to toe with a muslin cloth and presented himself to unsuspecting individuals in a variety of settings. In his first study, he emerged from behind a small mound in a cow pasture, strolled to the next mound, and then abruptly vanished behind it. To his chagrin, none of the eighty or so passersby gave any sign of having seen him (although apparently the local cows found him fascinating). He hoped that the setting of his second attempt would produce better results: the graveyard of a church. Sadly, he was again disappointed. Of over 140 potential witnesses to his “Experimental Apparition,” only four appeared to notice anything unusual. Matthew Tompkins describes their reactions as follows:

Under questioning, it emerged that none of them believed they had witnessed anything remotely paranormal. The first person described the apparition as “a man dressed as a woman, who surely must be mad” another assumed that it was “an art student walking about in a blanket.” Two witnesses, when questioned together, did realise that the Experimental Apparition was probably intended to simulate a paranormal event, but went on to note that the effect was spoiled because “we could see his legs and feet and knew it was a man dressed in some white garment.”29

Undeterred, Cornell had one last attempt to collect the data he wanted. This time, his Experimental Apparition took fifty seconds to walk from one side of a cinema screen to the other and back again in front of the audience for an X-rated (that is to say, adult) movie. He chose this setting partly because he felt that this would ensure that his witnesses were focusing their attention in the right direction, and partly to ensure that no children would be traumatized by the experience. He need not have worried. In Tompkins’s words:

None of the audience reported anything remotely paranormal. Many saw nothing unusual at all: 46% of the respondents had failed to notice the Experimental Apparition when Cornell first passed in front of the screen, and 32% remained completely unaware of it. Even the projectionist, whose job was to watch for anything unusual, reported that he had completely failed to notice the apparition. Those that did see ‘something’ were not particularly accurate in their descriptions. One person reported seeing a woman in a coat, another thought they had seen a polar bear, and another believed that they had observed a fault in the projector. Only one person accurately described a man dressed in a sheet pretending to be a ghost.

Cornell was disappointed by his results, having no inkling that the phenomenon he had so strikingly demonstrated would become a major focus of psychological research several decades later. Of course, in his case, inattentional blindness had caused people to miss the ostensibly paranormal phenomenon itself, as opposed to any potential explanations for such phenomena. In fact, on the basis of his results, Cornell suggested that there may actually be many more ghosts around than is generally appreciated but that people simply fail to notice them!

The Fallibility of Memory

As Cornell’s experiments, along with literally thousands of others, clearly demonstrate, eyewitness testimony can be extremely unreliable. This is a fundamental lesson to bear in mind whenever one is presented with anecdotal evidence in support of a paranormal claim. As David Hume asked, is it more likely that an event occurred that violated the laws of nature as we currently understand them or that the claimant is mistaken (or lying)?

One of the main reasons that the unreliability of eyewitness testimony has been the subject of so much research is because of its obvious implications for the legal system. The reliance on eyewitness testimony in many criminal trials when making life-changing decisions regarding guilt or innocence continues despite the findings from countless psychological experiments clearly demonstrating the frailty of human memory.30 Of course, the findings from such studies generalize beyond the forensic context to autobiographical memory in general, including memory for anomalous experiences.31

Such research has confirmed a number of commonly held beliefs that coincide with our intuitive expectations of how memory works. For example, it comes as no surprise that memory for peripheral detail is poorer than memory for that which is the focus of our attention, that memory is worse for things seen only briefly or under imperfect viewing conditions, and that memory is less accurate when we are underaroused (e.g., sleepy) or overaroused (e.g., terrified). It is noteworthy that many of the factors just listed often apply to reports of ghostly encounters. Lest the reader conclude that memory science has achieved nothing more than confirming what everyone already knew, it should be noted that many other commonly held beliefs about memory have been shown to be completely false, a fact that has worrying implications for our legal system.32

One of the most widely held misconceptions about memory is the notion that memory works like a video camera, accurately recalling every detail of everything we ever experience.33 In fact, both memory and perception are constructive processes. With respect to perception, despite our intuition that we take in and process all of the available sensory information around us at every instant, we actually process only a small fraction of it. How then are we able to build up and maintain that mental model of the world around us and our place within it that is the basis of our sense of being a single unified consciousness?

It is generally accepted that we perform this near-miraculous feat on the basis of two sources of information. On the one hand, we do of course process information coming in via our all of our senses. This is sometimes referred to as bottom-up processing. But, as already stated, we actually only fully process a fraction of the sensory information available to us from moment to moment. How then does our brain, without our conscious awareness, fill in the gaps to give us the impression that we have a complete mental model of the world around us? This is achieved via top-down processing. We are able to fill in the gaps in our mental model on the basis of what we already know about the world through our prior experience. Thus, our mental model is based on the constant interaction between bottom-up and top-down processing. The model is constantly updated on the basis of new incoming sensory information.

In general, this system works well and provides us with a mental model that is usually reliable enough for us to safely interact with the world. If we had to process every single detail of every single sensory channel before we had a reliable mental model, the system would simply overload. However, this process of filling in the gaps in our mental model on the basis of expectations built up from prior experience means that there is the potential for illusory perceptions, especially if the current input is degraded or inherently ambiguous. Thus, we may end up perceiving things that are not there.

It may be more accurate to describe memory as a reconstructive process rather than a constructive process. Every time you recall something, you do so on the basis of more or less accurate memory traces laid down at the time the event occurred, but once again you will unconsciously fill in any gaps on the basis of top-down processing. We may thus end up with memories based on what we think must have happened rather than what actually did happen.

As a striking illustration of this, see if you can answer the following question: Without actually looking at any clocks or watches, can you remember how the number four is represented on clocks and watches with Roman numerals on them? As I know from asking this question in countless public talks, most people confidently reply that it is represented as “IV”—and are quite surprised to learn that on the vast majority of such timepieces it is, in fact, represented as “IIII.” Everywhere else it is indeed represented as “IV”—but not on clocks and watches.34

That particular example of a memory error caused by top-down processing has a special place in my heart. My wife, Anne Richards, and I carried out an experimental investigation of this effect that was published in the British Journal of Psychology.35 That paper was, without a doubt, the one that required the least effort of all the papers that we ever published. We collected the data on a single afternoon from volunteers attending an open day at Goldsmiths. Data were collected from three groups. The first group was shown an ordinary clock (our kitchen clock, in fact) with Roman numerals on its face for one minute. The clock was then removed from view and participants were instructed to draw it from memory. The procedure for the second group was identical, with the exception that this group was informed in advance that they would be required to draw the clock from memory. The third group was simply asked to draw the clock with the clock remaining in full view throughout. The results were striking. In both of the memory groups, most participants incorrectly represented the four as “IV.” In the copy group, no one did.

In our paper reporting these results, we described how this curious phenomenon first came to our attention. We were visiting my wife’s parents. Our eldest daughter, Lucy, was about eight years old. Her attention was caught by a clock on the mantlepiece. Here, extracted from our paper, is the conversation that then took place:

Lucy On the clock, why does “V” come after “IIII”?

CCF (without looking at the clock) It doesn’t say “IIII.” It says “IV” for four.

Lucy It doesn’t. Look.

CCF (looking at clock) Incredible! You’d think clock-makers of all people would know Roman numerals! But this is how it should be. (Shows his wrist-watch.) Would you believe it, they’ve got it wrong on here as well!

These days, Anne insists that she had the above conversation with Lucy. She is wrong, of course, thus providing us with another nice example of memory distortion (hers, not mine).36 Regardless of that, we wrote up the paper in a couple of hours, submitted it, and were requested to revise only a single sentence before it was suitable for publication. If only it was so straightforward to get all scientific papers published! Our one regret is that we did not christen this particular example of memory distortion as the Lucy effect (sorry, Lucy!).

Once one appreciates the reconstructive nature of memory, one can understand why one’s memory of an event depends not only on what was happening when the experience itself was happening but also on events that preceded and followed it. Your prior experiences will lead you to have a particular set of beliefs and expectations that will then influence how you perceive what is going on around you, especially if those events are ambiguous and unclear (as in pareidolia, for example). You will subsequently recall your interpretation of the event, not the event itself. As the event itself is taking place, you will only recall those aspects that were encoded at the time as demonstrated by studies of inattentional bias. You will also be affected by suggestions made at the time. Once the event has taken place, it can still be distorted further by events that take place subsequently. All of these effects have been demonstrated in thousands of psychological studies, including many in the area of anomalistic psychology.

Memory for Faked Séances

In order to systematically study the reliability of memory, we need to consider alternatives to reports of spontaneous ghostly encounters. The latter occur at unpredictable times and places, and objective records of what actually happened are typically unavailable. If we need to assess how accurate someone’s recall is, we need to know exactly what was taking place at the time so that we can compare this with the individual’s report. The experiments reported by Cornell provide one approach to this issue, but there are alternative approaches. One of these is to assess how well people recall the events that take place during a faked séance.

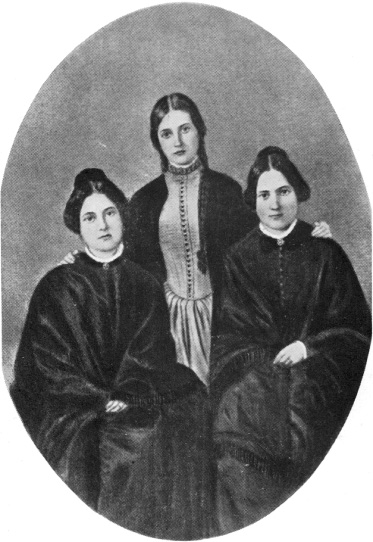

Séances were all the rage in the Victorian era, a period during which Spiritualism grew enormously in popularity.37 We can date the origins of the Spiritualist movement very precisely. In March 1848, in a house in Hydesville, New York, two young sisters by the name of Kate and Margaretta Fox (figure 3.3) reported hearing strange rapping noises and eventually discovered that they could communicate with “the other side” using a simple code. They claimed that the noises were made by the spirit of a peddler who had been murdered and buried in the cellar. Soon others also claimed to be able to communicate with the dead, and séances spread like wildfire across America and Europe.

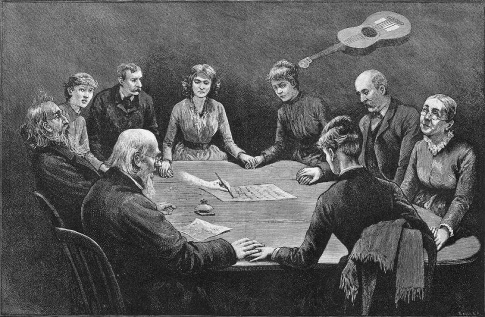

Séances eventually came to involve other phenomena too, including movement of tables and objects; the playing of musical instruments by unseen hands and lips; strange lights in the dark; levitation of objects, the table, or even the medium; the disappearance or materialization of objects; the materialization of hands, faces, or even complete spirit forms (ostensibly composed of “ectoplasm”); disembodied voices; spirit paintings and photographs; and written communications from the spirit world (figure 3.4). All of these phenomena were said to be produced by spirits summoned by the medium.

Figure 3.3

The Fox sisters (from left to right): Margaretta, Kate, and Leah. Elder sister Leah acted as manager for her younger sisters for a time.

Figure 3.4

During typical séances in the Victorian era, sitters were instructed to hold hands and remain in their seats throughout the proceedings.

Unfortunately, it was a very rare medium indeed who was not caught at some point engaging in trickery to produce these effects. In 1888, Margaretta Fox admitted that the original rapping noises produced forty years earlier, when she was just a girl, were not in any way psychic. They were produced in a variety of ways but mainly by cracking her toe and ankle joints, a skill she demonstrated in public. What had begun as a prank got out of hand, and the sisters felt unable to own up. Spiritualists simply refused to believe the confession, and the movement continues to this day.

Interestingly, the first systematic study of the unreliability of eyewitness testimony took place in the context of a faked séance. It was reported by S. John Davey in the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research in 1887.38 Ray Hyman provides the following account:

Davey had been converted to a belief in spiritualistic phenomena by the slate-writing demonstrations of the medium Henry Slade. Subsequently Davey accidentally discovered that Slade had employed trickery to produce some of the phenomena. Davey practised until he felt he could accomplish all of Slade’s feats by trickery and misdirection. He then conducted his well-rehearsed seance for several groups of sitters, including many who had witnessed and testified to the reality of spiritualistic phenomena. Immediately after each seance, Davey had the sitters write out in detail all that they could remember having happened during his seance. The findings were striking and very disturbing to believers. No one realized that Davey was employing tricks. Sitters consistently omitted crucial details, added others, changed the order of events, and otherwise supplied reports that would make it impossible for any reader to account for what was described by normal means.39

In 1932, Theodore Besterman reported similar levels of memory distortion in the recall of his faked séance.40 Sitters reported objects as having moved during the séance when they had not as well as failing to report important events such as the experimenter actually leaving the room. This line of research was continued more recently by Richard Wiseman and colleagues with a particular emphasis on investigating the power of suggestion.41 In one experiment, the actor playing the part of the medium suggested the table was moving when in fact it was not. Afterward, one-third of the participants incorrectly reported that the table had moved. Believers in the paranormal were more susceptible to this suggestion than nonbelievers. In a second experiment, it was found that once again believers in the paranormal were more susceptible to the effects of suggestion, but only if the suggestion was consistent with their belief. Although all of the effects demonstrated in the séances were produced by trickery, many participants reported that they believed that they had witnessed genuinely paranormal phenomena.

As an aside, it is also worth noting that the anomalous sensations reported by participants in this study were not limited to the mysterious movement of objects. As Wiseman and colleagues report:

Many people reported the type of quite dramatic phenomena often associated with ‘genuine’ seances, including being in an unusual psychological state (e.g. ‘Feeling of depersonification and elation when the objects moved’); changes in temperature (e.g. ‘Cold shivers running through my body when I concentrated hard on moving the objects’); an energetic presence (e.g. ‘A strong sense of energy flowing through the circle which increased’); and unusual smells (e.g. ‘A smell of hot plastic, combination of sweet and acrid smell’). Thus, the fake seances caused participants to report many of the experiences described by those attending ‘genuine’ seances, suggesting that such effects are the result of psychological processes (e.g. psychosomatic experiences brought about by participants’ heightened expectations or strong beliefs), rather than being caused by paranormal, psychic or mediumistic mechanisms.42

Memory for Other Ostensibly Paranormal Phenomena

The effects of prior belief in the paranormal were also demonstrated in an investigation by Richard Wiseman and Robert Morris of the recall of what they called “pseudo-psychic demonstrations”—or what you and I might call “conjuring tricks.”43 Participants were misled into believing that an individual had presented himself to the Koestler Parapsychology Unit at the University of Edinburgh claiming to possess genuine paranormal abilities. They were then shown videos of this individual performing conjuring tricks that appeared to demonstrate effects that are often presented as being paranormal. Finally, they were asked to rate the degree to which they thought the phenomena were genuinely paranormal and also to answer a number of recall questions.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the believers in the paranormal rated the demonstrations as more “paranormal” than did the skeptics. Of greater interest were the results of the memory tests. Wiseman and Morris had asked about recall for both “important” and “unimportant” details of the demonstration. By this they meant that some aspects of the demonstrations were completely unrelated to the methods used to achieve the apparently paranormal effects. These were the unimportant details. But some aspects of the demonstration did indeed provide potential clues to the trickery that was being employed. For example, a couple of the video clips appeared to demonstrate psychokinetic metal-bending of the kind made famous by Uri Geller, in one case the apparent bending of a key.44 This was achieved by using sleight of hand to surreptitiously switch the originally straight key for a pre-bent copy partway through the performance. This can only be achieved if the key passes out of sight for a split second at some point. This was precisely the kind of detail that the skeptics were more likely to recall than the paranormal believers. Skeptics and believers did not differ in the accuracy of their recall for unimportant details.

The most obvious explanation for this effect is that the two groups of participants approached the task with different intentions. The skeptics were more likely to be in problem-solving mode, assuming the effects would be achieved by trickery and actively trying to spot the techniques being used. They would, therefore, be more likely to actually spot the clues and recall those details accurately. The believers, on the other hand, would be more likely to assume that they were about to witness genuine paranormal effects and therefore would just sit back and enjoy the show. As we know from research into inattentional blindness, if information is not encoded at the time an event occurs, it will simply not be available for recall later.

Although most magicians are convinced that apparent psychokinetic metal-bending is always the result of trickery, many people who witnessed Uri Geller performing this feat early in his career were not convinced by this scientific explanation. One of their main reasons for rejecting this explanation was, they claimed, that the metal object in question continued to bend even after Geller had put it down! How could that possibly be achieved by sleight of hand?45

I suspect that by now readers may already have guessed the explanation for these claims. Was it possible that the reports of spoons, forks, and keys that continued to bend after they had left Geller’s hands were based on nothing more than the power of suggestion, as demonstrated in the fake séance studies? Suspecting that this may well be the case, Richard Wiseman and Emma Greening put this explanation to the test under properly controlled conditions.46 Participants were once again presented with a video clip showing an alleged psychic claimant apparently performing a psychic key-bend. In fact, of course, the effect was achieved using sleight of hand. In one condition, after the key had been bent, it was placed on the table and, with the key still in full view, the “psychic” can be heard suggesting, “It’s still bending.”47 Participants in the other condition were shown an identical video with the single exception that no suggestion was made that the key continued to bend. Around 40 percent of the participants who received the suggestion reported that they thought the key carried on bending compared to only one (out of twenty-three) in the no-suggestion condition.

This effect was replicated in a second experiment. In this second experiment, it was found that those who reported that the key continued to bend were more confident in the accuracy of their own memory than those that did not and also were less likely to recall that the “psychic” had explicitly suggested that the key continued to bend. Surprisingly, given previous similar studies, believers in the paranormal were not found to be more susceptible to suggestion.

Not long after this report was published, I was involved in demonstrating the effect for a TV company. In this case, we wondered how impactful it might be to witness such an effect live as opposed to watching a prerecorded video. In this case, fellow skeptic and amateur magician Tony Youens played the role of our psychic, using a nail instead of a key. By the end of the day, we had enough shots of our volunteers expressing their amazement at the nail that, they claimed, they had seen continuing to bend as it lay in Tony’s palm following his psychokinetic exertions.

One of the most memorable aspects of that day’s filming was the reaction of our cameraman. Before we started filming, he told me that he had seen Geller performing his metal-bending feat back in the 1970s, and he had seen with his own eyes that the metal had indeed continued to bend even after Geller put it down. So, by the end of the day, was he now convinced that this was due to nothing more than the power of suggestion? Not on your life!

Given the overwhelming evidence that eyewitness testimony can be so unreliable, there are reasonable grounds to be cautious in taking the uncorroborated testimony of a single eyewitness at face value. Does it make sense to give more evidential weight to those situations when there is more than one eyewitness and they all give similar accounts? The short answer is yes—but even here, there is the potential for serious memory distortion. One factor that may lead to such distortion is referred to as memory conformity. This refers to the phenomenon whereby one eyewitness’s account may influence the memory of a second eyewitness. If the first person’s account is inaccurate in some ways, those inaccuracies may be unintentionally incorporated into the second person’s memory.

Memory conformity is one example of the more general phenomenon of memory distortion due to post-event misinformation. Psychologists have for many decades successfully distorted the memories of witnesses by subtly presenting them with misinformation following the viewing of, say, a simulated crime scene. Elizabeth Loftus and colleagues carried out research using this technique.48 For example, in one study participants were shown a sequence of slides depicting events before, during, and after a car accident in which a pedestrian was injured. Half of the participants saw a slide showing a red Datsun at an intersection with a stop sign in the background. The other half saw the same scene but with a yield (give way) sign in place of the stop sign.

After seeing the slides, participants were interviewed using a standard questionnaire. One of the questions was deliberately misleading for some participants. For example, half of the participants who had viewed a stop sign were asked, “Did another car pass the Datsun while it was stopped at the stop sign?,” but the other half were misled by being asked, “Did another car pass the Datsun while it was stopped at the yield sign?” (italics added). Similarly, half of the participants who had actually originally viewed a yield sign were asked a question implying that a stop sign had been viewed, with the other half being asked the question in a nonmisleading form. Presentation of misleading information in the post-event question increased the probability that participants would subsequently report seeing a sign that was different than the one that they had actually seen. Since that early work, there have been innumerable variations of the original technique leading to one indisputable conclusion: exposure to misleading information about an event after the event has taken place often distorts a witness’s memory of it.

Some more recent post-event misinformation studies are characterized by the presentation of misleading information via a social channel, typically discussion with a co-witness. Witnesses to an unusual and unexpected event, such as a crime, a possible ghostly encounter, or a UFO sighting, are likely to spontaneously discuss what they have seen prior to any formal interview. Studies of memory conformity often involve getting volunteers to watch a video of a staged crime and then discuss it in pairs prior to giving an independent report of what happened. In some studies, one of the members of the pair is in fact a confederate of the experimenters who has been instructed to introduce a few specific items of misinformation (e.g., what the perpetrator was wearing) into the discussion.49 This misinformation is often incorporated into the account subsequently given by the genuine participant.

My friend Fiona Gabbert, now a professor of psychology at Goldsmiths, and colleagues used a novel technique whereby pairs of volunteers watched a short film of the same staged crime but viewed from different angles.50 The filming was carried out in such a way that version A included some details that could not be seen in version B and vice versa. The pairs of volunteers were under the impression that they had both watched the same video. After watching the video, the pairs discussed what they had seen and then independently answered questions regarding their recall of the events. Regardless of the technique used, studies of memory conformity routinely demonstrate that information (or misinformation) only available via a co-witness’s report is incorporated into accounts provided by a significant proportion of witnesses.

Krissy Wilson, at that time one of my postgraduate students, and I decided to investigate memory conformity effects in an anomalistic context.51 To do so, we used the same video clip that Richard Wiseman and Emma Greening had used in their “It’s still bending” study described above. We incorporated a memory conformity element into our study by having participants watch the video in pairs and then discuss it together prior to giving independent reports of what they had seen. As in previous studies, one member of each pair was in fact a confederate who had been instructed to say either that the key continued to bend after it had been placed on the table or to say the key did not continue to bend. In a third condition, the confederate remained neutral, not commenting on it at all. Our results showed that both the suggestion from the fake psychic and the comments from the stooge co-witness had an effect on the reports of the genuine participants. Indeed, around 60 percent of the participants who were in the condition in which they received both the suggestion from the psychic and the reinforcement of this suggestion from the stooge reported that they thought the key carried on bending. In our study, believers in the paranormal were indeed found to be more susceptible to suggestion, possibly as a result of us using a different measure of paranormal belief than that used by Wiseman and Greening.

As demonstrated in the experiments described above, as well as literally thousands of other published studies, eyewitness testimony can be notoriously unreliable insofar as memory for an event can be distorted by experiences that take place before, during, and after the event in question. In fact, we can even have apparent memories in our minds that are not just distorted memories of events we have witnessed but are apparent memories for events that never actually happened. We shall defer further discussion of these false memories until a later chapter where they are arguably more relevant. For now, it should be borne in mind that any individual paranormal anecdote may not just be a distorted version of an event that really happened—it may be a complete fabrication from start to finish, albeit one that was unintentionally generated and is now sincerely believed.

Environmental Factors Associated with Hauntings

There is, as already discussed, evidence that when people are told that a location is haunted, they tend to report more anomalous experiences there than people who are not primed in this way. This is to be expected given what we know about the power of suggestion. But is it also possible that some locations are just inherently spookier than others? This possibility was investigated in two studies, one at Hampton Court Palace, the other at the South Bridge Vaults in Edinburgh, carried out by a team led by—yes, you’ve guessed it—Richard Wiseman.52 Both locations have considerable reputations for being haunted, but, interestingly, within each some areas are reported to be more haunted than others; that is to say, that whereas visitors report a high number of anomalous experiences in some areas, very few are reported in others.

Visitors were asked to walk around the locations and to note any anomalous experiences they had and where those experiences had occurred. One might expect that visitors who already knew something about each location in terms of which areas were reputed to be the most haunted would, by a process of what we might call self-priming, duly report more anomalous experiences in the “haunted” than the “nonhaunted” areas, whereas this pattern would not be observed for visitors who did not possess such knowledge. In fact, this is not what was found. Instead, there was a general tendency for more anomalous experiences to be reported in the “haunted” areas than the “nonhaunted” areas by all visitors, regardless of their prior knowledge. This strongly supports the notion that some locations are just inherently spookier than others, possibly as a consequence of environmental factors.

Fortunately, Wiseman and his team collected data relevant to investigating this notion. Analysis of the data from the Edinburgh study showed that people reported more anomalous experiences when going from a relatively well-lit exterior to the dark interior of a vault than when entering a vault with less discrepancy between exterior and interior lighting levels. This is perhaps not a surprising result, as it is a natural human response to feel more vulnerable in the dark. From an evolutionary perspective, our ancestors were at much greater risk from potential threats in conditions of dim illumination. The same argument might apply to another finding from this study; that is, more such experiences were reported in vaults with higher ceilings. Again, from an evolutionary point of view, one might argue that it makes sense for humans to be more alert on entering caves with high ceilings given the possibility that an attacker might suddenly drop on them from above.

Another suggestive finding, however, cannot be explained in such terms. In the Hampton Court Palace investigation, it was found that, although there was no significant difference in the strength of the local magnetic fields between the “haunted” and the “nonhaunted” areas, the variance in the fields was significantly greater for the former.53 Furthermore, the variance correlated with the number of anomalous experiences reported in each area. No such pattern of results was found in the Edinburgh investigation, however, suggesting that this may be a spurious finding.

Some readers may wonder why these investigators were measuring magnetic fields in the first place. What on earth could they have to do with reports of ghostly encounters? They were gathering data relating to an interesting, albeit controversial, theory put forward by the late Canadian professor of psychology, Michael Persinger.54 For several decades, Persinger had been arguing that a range of ostensibly paranormal and religious experiences might actually be the result of unusual activity in the temporal lobes of the brain, causing hallucinatory experiences of the type often associated with reputedly haunted locations. Furthermore, such neuronal activity, he argued, could be induced in susceptible individuals if they were exposed to certain types of weak, complex electromagnetic fields.

Before we go any further, it should be pointed out that there is, in fact, absolutely no doubt that exposing brains to strong magnetic fields can have immediate and unambiguous effects. A technique known as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) has become increasingly popular among neuropsychologists as another method to investigate brain function. TMS involves the application of simple, high-intensity magnetic pulses near the cranium that are known to be strong enough to induce currents within areas of the brain that are close to the source of the field. The biophysics of the technique is well understood. The technique provides a way of studying brain function by essentially temporarily “knocking out” specific parts of the brain so that the effects on cognition, behavior, and subjective awareness can be assessed. The technique is also used in diagnosis and treatment.

What is happening when TMS is applied is very different from the kind of effects claimed by Persinger, as pointed out by Jason Braithwaite.55 Whereas TMS involves the use of simple, high-intensity magnetic pulses, Persinger claims that anomalous experiences may be induced in the presence of weak yet complex electromagnetic fields. Indeed, it has been pointed out that Persinger’s fields are about 5,000 times weaker than that produced by a typical fridge magnet!56 There is currently no plausible biophysical mechanism whereby such weak magnetic fields could have an effect on brain function. Whereas the effects of TMS on brain function are instantaneous, definite, and specific, Persinger claims that the effects of the weak fields that he is referring to take time to build up (some twenty to forty minutes) and are rather nebulous in nature. Furthermore, TMS works on everyone, whereas according to Persinger you will only have anomalous experiences as a result of exposure to weak, complex electromagnetic fields if you already have sufficiently labile temporal lobes. Persinger gauges the lability of an individual’s temporal lobes by administering his Temporal Lobe Signs Inventory, which is a subscale on his Personal Philosophy Inventory.57

Braithwaite has comprehensively reviewed the evidence for and against Persinger’s claims of a link between electromagnetic fields and anomalous experiences.58 The evidence put forward in support of these claims is primarily of three types. First, Persinger claimed the number of anomalous experiences reported is significantly correlated with changes in the Earth’s background electromagnetic field. This would appear to be highly unlikely, given that one would experience much greater fluctuations in electromagnetic fields walking through the average home as a result of the use of electronic devices. It is likely that the significant correlations reported by Persinger are simply the result of data-trawling through massive data sets until spuriously significant correlations were found.

The second line of evidence is the claim that magnetic anomalies are more frequently found in reputedly haunted locations than in appropriately matched control locations. It turns out, however, that only two examples of the type of temporally complex fields that Persinger claims are required to induce hallucinatory experiences have been reported from around fifty locations investigated. Whether the fields in these two cases played any direct role in the anomalous experiences reported in these cases is a moot point, but these studies do not provide support for the idea that weak, complex electromagnetic fields are a major factor underlying reports of ghostly encounters.

The third and final strand of evidence comes from laboratory studies. Persinger claimed that he could induce the required pattern of unusual activity in the temporal lobes of susceptible volunteers by getting them to wear a specially constructed helmet that could generate the appropriate weak-intensity, temporally complex electromagnetic fields near their craniums. Although Persinger referred to this device as a “Koren helmet,” others tend to call it the “God helmet,” as Persinger claimed that the experiences induced were often interpreted as religious experiences.

Persinger published many papers with results from experiments using the God helmet, reporting a range of anomalous experiences.59 It was even claimed that application of the technique had led to the subjective experience of a full-blown apparition in a middle-aged man with a prior history of such experiences.60 As one might expect, this line of research has received much media attention. It has been featured in two Horizon documentaries produced by the BBC. In the first, in 1994, renowned skeptic Susan Blackmore volunteered to don the helmet as she lay back in a dentist’s chair in a soundproof room in Persinger’s laboratory. For the first ten minutes, nothing happened. Here is her description of what happened next:

Then it felt for all the world as though two hands had grabbed my shoulders and were bodily yanking me upright. I knew I was still lying in the reclining chair, but someone, or something, was pulling me up.

Something seemed to get hold of my leg and pull it, distort it, and drag it up the wall. It felt as though I had been stretched half way up to the ceiling. Then came the emotions. Totally out of the blue, but intensely and vividly, I suddenly felt angry—not just mildly cross but that clear-minded anger out of which you act—but there was nothing and no one to act on. After perhaps ten seconds, it was gone. Later, it was replaced by an equally sudden attack of fear. I was terrified—of nothing in particular.61

A decade or so later, Horizon featured Persinger’s God helmet again, this time in a program titled God on the Brain. On this occasion, the presenter was Richard Dawkins. After trying the God helmet, Dawkins reported, “It pretty much felt as though I was in total darkness, with a helmet on my head and pleasantly relaxed.” In the words of Craig Aaen-Stockdale, “Not exactly a road to Damascus experience, but Dawkins is, of course, a damned sceptic and Persinger simply argued that he wasn’t temporal-lobey enough.”62

The main problem with this body of evidence is that, by and large, it has all been produced by a single laboratory—that of Michael Persinger himself. Furthermore, concern has been expressed over the degree to which Persinger employed proper double-blind methodologies in his published research. In studies using double-blind methodologies, neither the participant nor the experimenter is aware of whether the participant is in the experimental or the control condition until data analysis has been completed. That way, there is no possibility of bias, either intentional or unintentional, affecting the results.

There is an urgent need for independent replication of Persinger’s results by other laboratories using appropriate double-blind methodologies. One attempt to do this was reported by Pehr Granqvist and colleagues.63 They used equipment borrowed directly from Persinger’s laboratory but were unable to replicate his finding of a link between the application of weak, complex electromagnetic fields and reports of a sensed presence. Instead, they found that scores on various measures associated with suggestibility, including absorption, temporal lobe signs, and New Age lifestyle orientation, correlated with the tendency to report such experiences. Their report was highly critical of Persinger’s research, arguing that his findings may reflect little more than the effects of priming, suggestibility, and poor methodology. Predictably, Persinger rejected these criticisms, but it remains the case that, without more supporting evidence from independent researchers, the wider scientific community is unlikely to accept Persinger’s claims.64 Braithwaite concludes his examination of the evidence by advocating a position that “acknowledges the possibility of an effect, but an effect which is rare and requires considerable further investigation.”65

A second invisible environmental factor has also been suggested as possibly producing similar anomalous experiences: infrasound. Infrasound is sound energy below the audible frequency range (i.e., lower than 20 Hz). The late Vic Tandy, inspired by his own ghostly encounter, put forward the idea that infrasound is capable in some circumstances of inducing hallucinatory experiences, including a sense of presence, feelings of depression, cold shivers, and even apparitions.66 On more than one occasion, I had the pleasure of listening to Vic recount the story of how he first came up with his theory in front of rapt audiences. It is a good story, well worth summarizing here.

Vic used to work for a company producing medical equipment. The laboratory had a reputation for being haunted, but Vic never took the reports of strange experiences seriously until he had one himself. Working late one night, alone in the lab, he started to feel uncomfortable. He felt depressed. He was sweating even though it was cold. He also had a strong sense of presence. As he wrote at his desk, the feeling that someone—or something—was watching him grew stronger. He slowly became aware of a blurry gray figure on his left, in the periphery of his vision. Terrified, he managed to pluck up the courage to turn and face the apparition—at which point it simply faded away. Convinced that he was cracking up, he went home.