4

High Spirits, Part 2: Communicating with the Dead

Mental Mediumship

Reports of ghostly encounters are not the only evidence put forward to support the existence of spirits. Throughout history, there have been many reports of communication with the dead. Of course, the important thing here is that the communication is two-way. William Shakespeare makes this point nicely in his play, King Henry IV, Part 1. Glendower boasts to Hotspur, “I can call the spirits from the vasty deep.” Hotspur’s reply: “Why, so can I, or so can any man; But will they come, when you do call for them?”

We have already considered one such claim. The Fox sisters claimed that the rapping sounds heard in their house in Hydesville, New York, were produced by a spirit, and they claimed to be able to communicate with that spirit using a simple code based on the number of knocks. As the Spiritualist movement grew, séances became more elaborate, often involving a wide range of physical effects. Mediums who specialized in this type of séance are referred to, unsurprisingly, as physical mediums, in contrast to mental mediums, who claim that they are able to pass messages between the living and the dead. These days, the latter vastly outnumber the former.

Mental mediumship can sometimes involve one-to-one readings, sometimes be done for a small group, and sometimes be performed in front of large audiences in packed theaters. Professional mediums typically charge for their services, and some become celebrities in their own right, with their own TV shows, bestselling books, and online services. Famous modern examples in the United States include Sylvia Browne, John Edward, and James Van Praagh, while in the United Kingdom the list includes Derek Acorah, Colin Fry, Sally Morgan, and Doris Stokes.

Mental mediums typically appear to go into a trance during their séances. It is claimed that they are then able to “channel” messages from the spirit world. They may do this directly or by means of a spirit guide who acts as an intermediary between the medium and the spirit in question. Sometimes they will even appear to be temporarily possessed by a spirit, resulting in dramatic changes in their voice, mannerisms, and occasionally, it is claimed, their very appearance.

Séances reached the height of their popularity in the Victorian era. Indeed, their popularity was one of the factors that led to the founding of the Society for Psychical Research in the United Kingdom in 1882, followed by the founding of the American Society for Psychical Research a few years later. The other main factor was as a reaction to an obvious implication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published in 1859. Darwin’s work clearly cast doubt on the idea that humans were God’s special creation—and therefore the idea that humans had an immortal soul. The hope was that by applying the scientific method to the question of postmortem survival, proof would be forthcoming that the Christian belief in life after death was valid. The obvious place to start was by testing the claims of the numerous mediums of the day.

Initially there was cooperation between the scientists and the mediums, but this waned as the former were keen to apply greater controls in their investigations. After all, the conditions that typically applied during the séances, of dim illumination and a prohibition on sitters moving around, were ideal conditions for the employment of trickery by the medium and any accomplices. As previously stated, it was indeed a rare medium who was not caught red-handed in executing such deception. Many scientists were dismissive from the start and refused to even look at the evidence. Many of their more open-minded colleagues eventually decided that this was not a fruitful line of inquiry and concluded that no genuinely supernatural phenomena were taking place in the séance room. However, a few notable scientists of the day were convinced of the genuineness of the phenomena that they witnessed, including Alfred Russell Wallace, who had independently come up with the idea of evolution by natural selection at about the same time that Darwin did, and Sir William Crookes, the discoverer of thallium.

Early attempts to evaluate the accuracy of mediums were typically not methodologically sound. For example, an investigator who is keen to find evidence in support of life after death may well be inclined to count many more of the mediums’ often-ambiguous pronouncements as accurate compared to someone without that motivation. Furthermore, a simple tally of accurate versus inaccurate statements is of very limited value. After all, if I simply came out with a lot of statements that had a very high probability of being true for everyone (“Your grandpa had two eyes, one on either side of his nose”), this would not constitute impressive evidence that I was in direct contact with your dearly departed ancestor, would it?

A better approach is to get the medium to make a number of readings for different individuals without actually meeting them. The sitters can then be presented with the reading that was actually produced specifically for them along with one or more readings produced for other sitters. If the medium’s claim to paranormal ability is true, the reading that really was done for that specific sitter should contain more accurate, personal, and specific details than the other readings. This can be evaluated either by getting each sitter to pick the reading that is most applicable to them or by giving an accuracy rating for each reading. The results can then be subjected to statistical testing. Such techniques were first developed and applied in the 1930s.

In 1994, Sybo Schouten published a review of such studies of both mediums and psychics up to that date.1 It should be noted here that the main difference between mediums and psychics is simply their technique. Whereas mediums claim to obtain information via the spirits of the dead, psychics may claim to use ESP. The readings produced are very similar. However, it should also be noted that in general it would prove impossible to decide whether information produced by a medium had actually been obtained via communication with a spirit as opposed to ESP.

Here is what Schouten concluded from his thorough review:

The main question asked in most of these studies was whether a significant number of correct statements deviated significantly from chance expectation. Another question, less often addressed, was whether psi ability was necessary to explain the correct statements. The present study indicates that the number of studies with significant positive results is rather small. Moreover, in most of these, one or more potential sources of error were present that might have influenced the outcome. It seems, therefore, that there is little reason to expect psychics to make correct statements about matters unknown at the time more often than would be expected by chance.2

A more recent review by Marco Aurélio Vinhosa Bastos Jr. and colleagues assessed studies of mediums carried out this century.3 Assessing accuracy, only five studies were considered to have adequately controlled for potential information leakage and to have employed a suitable triple-blind methodology. This methodology ensures that (a) the mediums are blind to the identities of both the sitters and the deceased persons known to the sitters; (b) the researchers are also blind to these aspects; and (c) the sitters do not know which readings were intended for them as opposed to being decoy control readings. Of these five studies, two reported significantly higher accuracy ratings for target ratings compared to decoy ratings and three did not.4 The two studies reporting significant positive results across three experiments, involving 28 mediums and 102 readings, were all carried out by Julie Beischel and colleagues at the Windbridge Institute in Tucson, Arizona. In contrast to many previous studies, there are no obvious major flaws in the methodology used or the statistical analysis employed. Once again, however, independent replication by other investigators is required before such controversial results are more widely accepted by the scientific community.

Cold Reading

The jury may still be out regarding the possibility that mediums and psychics, not to mention other diviners, really are able to tap into information sources in a way that cannot be explained by conventional science. However, there is no doubt at all that many members of the general public are convinced that they can. What possible alternative explanations are there for this?

One possibility is that all of these practitioners are deliberate frauds using deceptive techniques to persuade people to part with their money. Such techniques do indeed exist, and foremost among them is the practice of cold reading. Cold reading can be used to give complete strangers the impression that you know all about them even though you have never met them before. I used to joke with the students on my final-year course on anomalistic psychology that I would introduce them to the art of cold reading so that if they could not get a job once they graduated, they would have something to fall back on.

I will only be able to present a brief summary of cold reading here, but for any readers who would like to learn more (whatever their reasons!), I strongly recommend two publications. The first is a classic article, published in the first volume of The Zetetic in 1977 (before it changed its name to the Skeptical Inquirer), by Ray Hyman with the straightforward title “‘Cold Reading’: How to Convince Strangers That You Know All about Them.”5 It provides a great introduction to the topic as well as presenting Hyman’s “Rules of the Game.” The other is Ian Rowland’s book The Full Facts Book of Cold Reading, full of useful practical tips.6

Strictly speaking, it would be more accurate to describe cold reading as a set of techniques that work together to produce the desired effect. One such technique relies on a phenomenon known to psychologists as the Barnum effect. It is also sometimes known as the Forer effect, after a classic demonstration of this effect by psychologist Bertram R. Forer in 1949.7 Forer told his class of thirty-nine psychology students that he would provide each of them with a brief personality assessment based on their responses on a psychology test. In fact, unbeknownst to the students, each of them received identical feedback that was not based in any way on their responses on the test. Here are the statements that the students were given:

- 1. You have a great need for other people to like and admire you.

- 2. You have a tendency to be critical of yourself.

- 3. You have a great deal of unused capacity which you have not turned to your advantage.

- 4. While you have some personality weaknesses, you are generally able to compensate for them.

- 5. Your sexual adjustment has presented problems for you.

- 6. Disciplined and self-controlled outside, you tend to be worrisome and insecure inside.

- 7. At times you have serious doubts as to whether you have made the right decision or done the right thing.

- 8. You prefer a certain amount of change and variety and become dissatisfied when hemmed in by restrictions and limitations.

- 9. You pride yourself as an independent thinker and do not accept others’ statements without satisfactory proof.

- 10. You have found it unwise to be too frank in revealing yourself to others.

- 11. At times you are extroverted, affable, sociable, while at other times you are introverted, wary, reserved.

- 12. Some of your aspirations tend to be pretty unrealistic.

- 13. Security is one of your major goals in life.

The students were impressed with the accuracy of the statements as descriptions of themselves, giving an average accuracy rating of 4.30 on a scale where 0 = very poor and 5 = excellent. The point is, of course, that the statements had deliberately been chosen to be vague and general enough to apply to pretty much everyone while also sounding perceptive about the students’ innermost personalities. The Barnum effect has been the subject of a great deal of psychological investigation, not least because it proves that it would be unwise to judge the validity of any kind of psychological test purely on how accurate those tested reported it to be.8

Although Forer told his students that the profile was based on their responses on a psychology test, the effect is just as powerful if people are misled into believing that it is based on some form of divination. Indeed, it is worth noting here that Forer mainly used statements taken from an astrology book in the original experiment.

I have often combined those statements into a single paragraph and used them in demonstrations of the Barnum effect in the classroom and occasionally on TV. I have found that, particularly for public demonstrations where someone is asked to read the profile aloud before rating it for accuracy, it is wise to exclude statement no. 5 from the profile. This might indicate that people do not struggle with their sexual adjustment as much nowadays as they did in the 1940s, but I suspect it is more likely that most people would prefer not to endorse this statement in public even if it is true!

It is not that difficult to come up with your own Barnum-type statements. One that I am fond of is “You have a good sense of humor.” Of course you do, don’t you? Because if other people don’t laugh at things that make you laugh, they are the ones with the poor sense of humor, aren’t they? Furthermore, the statements need not only apply to your personality. I think it was Richard Wiseman who suggested throwing “I’m getting something about an unfinished book” into a reading. This is a clever one, because if that person happens to actually be writing a book, they will be incredibly impressed. How could you possibly know that? But if they’re not, they will think of a book that they are halfway through reading or one that they gave up on. Either way, you can’t lose.

The type of Barnum statements described above can be sprinkled liberally throughout any reading to pad it out, but a reading can be made somewhat more specific by taking into account demographic factors such as age and gender. After all, one would be unlikely to give similar readings for, say, a fourteen-year-old girl and an eighty-year-old man. Whereas the former is likely to want information about relationships and exams, the latter is more likely to be concerned about health and finances, for example. Furthermore, you may be able to deduce much from someone’s appearance and their accent regarding such factors as socioeconomic class.

There is, of course, much more to cold reading than simply trotting out generalities. Sitters often report being told specific details about themselves that could only, to their minds, be explained in terms of the ability to tap into some paranormal information source. Mediums and psychics are helped by the fact that sitters do not expect them to be 100 percent accurate. Indeed, it would probably arouse suspicion if the reader was too accurate. Given this, it is always worth throwing out a few statements that, although sounding very specific, apply to a surprisingly large percentage of the population.

In 1994, Susan Blackmore published ten statements in a national newspaper, asking readers to indicate which ones were true for them.9 From a sample of 6,238 respondents, over a quarter endorsed each of the following statements: “I have a scar on my left knee” (33.5 percent), “I have a cat” (28.7 percent), “I own a CD or tape of Handel’s Water Music” (28.3 percent), “I have been to France in the past year” (27.1 percent), “My back is giving me pain at the moment” (26.9 percent), and “I am one of three children” (26.4 percent). If such statements had been included in a reading back in the 1990s, there is a very good chance that one or more of them would have been endorsed by the sitter. It is likely that believers in the paranormal would obligingly remember the hits and forget the misses. They may even count near misses as hits. I recall that once, when I was appearing on a live radio phone-in with a medium, the caller agreed with the medium’s assertion that his father had died from lung cancer. Further probing revealed that the cause of death was actually stomach cancer, but clearly, for this caller, lung cancer was close enough. The idea that believers will tend to recall the hits and forget the misses is certainly plausible, but it would be nice to see it tested empirically. I suspect that skeptics may well show the opposite bias.

Selective recall can also result in readings being recalled as being more specific than they actually were. I once took part in a TV program in which volunteers were sent out to have readings done by different types of diviner. The readings were recorded as they were being delivered, and afterward the clients were asked to assess their reading. One young woman reported being particularly impressed that the psychic who had done her reading had correctly stated that her mother’s name was Sheila. No doubt she would subsequently relate this amazing psychic feat to friends and family, with no one able to provide an alternative, nonparanormal explanation. The only problem was that in fact the psychic never said that her mother’s name was Sheila. Instead, he came out with many names during her reading, most of which meant nothing to her. At one point, he said, “I’m getting the name Sheila . . .” To the young woman, it was obvious he was referring to her mother, who was indeed named Sheila. But he never actually said, “Your mother’s name is Sheila.” If her mother had not been called Sheila, she may well have thought of someone else she knew of that name, be it a friend, a neighbor, or whoever. The point is that the cooperative sitter was doing her best to make sense of what the psychic was saying and had put a very specific interpretation on one of the many vague utterances with which she was presented. Subsequently, she recalls that part of the reading as being much more specific than it actually was.

This observation directly inspired a study of the post-event misinformation effect described previously.10 Krissy Wilson and I presented volunteers with a video of an alleged psychic doing a reading for a client, followed by a postreading interview with the client. Or at least that is what we told our volunteers. In fact, both the reading and the postreading interview were scripted. Furthermore, there were two versions of the postreading interview, with half of the volunteers viewing one version, half viewing the other. During the reading, the “psychic” had said at one point, “I’m getting a name beginning with an ‘S’ or an ‘F’ . . . erm, is it? It’s Sharon . . . or Shelley . . . or Sandra . . . or Sheila?” The “client” replies, “Yes, yes”; that is, she does not explicitly state during the reading that Sheila is her mother’s name.

The two postreading interviews are identical with the exception of a single sentence. In one, the “client” correctly says, “He mentioned the name Sheila, which is my mother’s name.” In the other, she incorrectly says, “He said my mother’s name was Sheila, which it is.” Following the video, our volunteers were asked to indicate their level of agreement, on a 7-point scale (where 1 = strongly agree and 7 = strongly disagree), with a number of statements. The crucial one for our purposes was: “The psychic said that the client’s mother was called Sheila.” Given that this statement is in fact false, higher scores would indicate greater accuracy of recall.

Our results were interesting, albeit not in accordance with our original hypotheses. We had expected to find that the misinformation would distort the memories of all volunteers but that a stronger distorting effect of the misinformation would be found for believers in the paranormal compared to disbelievers, given that the misinformation made the reading seem more impressive than it was, in line with the belief that psychics have genuine paranormal ability. Instead we found that the paranormal believers inaccurately remembered what the “psychic” had said, thus recalling it as being more impressive than it really was, with or without the post-event misinformation. The nonbelievers, in contrast, recalled what the “psychic” had said pretty accurately when no misinformation was presented after the reading. When misinformation was presented, however, their recall became as inaccurate as that of the believers.

There are a couple of common misconceptions about how cold reading works that we should mention here. The first is that it largely depends on body language, also referred to as nonverbal communication. The idea is that people unconsciously give away lots of information about themselves through gestures, body position, eye movements, and so on. Such ideas have often been oversold, particularly in books about how to attract potential sexual partners or how to win in negotiations and so on. In fact, although such cues may occasionally provide some clues to enhance a reading, they play a minor role at best.

The second is what we might call the Sherlock Holmes fallacy. This is the idea that by applying flawless logic and keen observation one can deduce amazing amounts of specific background information about a person simply by looking at them. In fact, on some occasions, Holmes could allegedly perform such amazing feats before ever seeing the object of his deductions. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, he accurately deduces all of the following about Dr. James Mortimer simply by looking at his walking stick: “There emerges a young fellow under thirty, amiable, unambitious, absent-minded, and the possessor of a favourite dog, which I should describe roughly as being larger than a terrier and smaller than a mastiff.”11 Although such feats are hugely entertaining in the context of Holmes’s wonderful adventures, they are regrettably purely the stuff of fiction.

On one occasion, I was talked into passing myself off as a psychic on a popular daytime TV show in the United Kingdom (for British readers, I think it was Richard & Judy). When the researcher contacted me to take part in a discussion about psychics for the next show, I naturally gave her my spiel about cold reading and how it worked. “Great!” she replied. “Can you come on the show and demonstrate it for us?” I was very reluctant to do so. Just as not every client is impressed with the reading they get from a psychic, not all readings based on cold reading impress the person they are done for. But the researcher was persistent, and eventually I agreed to give it a go.

When the day arrived for me to go on the program, I was genuinely nervous. The idea was that I would be introduced to the volunteer sitter as a genuine medium, I would do a reading for her, and she would then comment on how impressive (or not) she had found the reading to be. This would all be prerecorded, and an edited version would be included as part of the live show. Even so, if my reading was a total flop, there would be no way to pretend it wasn’t.

One of Ray Hyman’s “Rules of the Game” is “Get the client’s cooperation in advance.” I decided to use my genuine nervousness to my advantage, explaining to the volunteer sitter that I was very nervous because this was the first time I had ever done a reading for TV. I also explained that I usually spend at least an hour with each client, but, as we only had ten minutes, it would really speed things up if she could tell me in advance if there was anyone in particular that she would like me to try to contact. So, I knew before I even started that granddad was “in spirit,” as we mediums say.

Fortunately for me, the reading went well. I knew from the many interactions between psychics and sitters that I had analyzed over the years that psychics tend to ask an awful lot of questions during a reading. When you think about it, this is a little bit odd given that they are supposed to be telling you stuff. But the thing is, they often do it in a rather clever way that makes it look like they are only asking for confirmation of something they already know. I decided to use this ploy during my reading. “Was your granddad a tidy man?” I asked. “Oh yes,” came the reply. “I thought so,” I said. “Everything had its place for your granddad, didn’t it?” Of course, if she had replied, “Oh no,” my response would have been, “I thought not. He never used to put things away after himself, did he?” My sitter was duly impressed.

I followed up with “And what about yourself? Are you tidy?” Once the sitter is convinced that you can read them like a book, they will often open up completely, as in this case. “Oh no,” she replied, “I’m terrible!” “I thought so,” I said again. “Your granddad’s saying that you’re always so messy. He’s saying it with love and a smile.” I went further. Following the advice in my recently reread copy of Ian Rowland’s book, I told the sitter that I had a mental image of her room and that I could see stacks of old photos that had not yet been put into albums. The truth is, of course, that before digital cameras became the norm, virtually every home would have such stacks of photographs—but this trivial detail really blew the socks off my sitter!

Now, as you might imagine, I felt a bit mean deceiving my volunteer in this way. The point was certainly not to make her look stupid or gullible but purely to demonstrate how effective the technique can be. Once the reading was over and her glowing review of my paranormal abilities had been recorded, she was informed that I did not really claim to have psychic powers and that I was using a technique called cold reading. I apologized for the deception and explained that we were not out to embarrass her in any way. She was given the option of vetoing the reading before it was broadcast if she wanted to. Fortunately, she was happy for it to be broadcast.

Let me make it very clear at this point that I do not believe for one second that all people claiming to be mediums or psychics—or indeed any other kind of diviner—are deliberate con artists using cold reading and other deceptive techniques to fleece their gullible victims of their hard-earned cash. My personal opinion, for what it is worth, is that most people who claim to have paranormal abilities genuinely believe that they do possess such abilities. They are fooling themselves as much as they are fooling others. There is also good evidence that many Spiritualist mediums really are hearing voices that they attribute to spirits of the dead. For example, Spiritualist mediums have higher levels of both absorption and proneness to auditory hallucinations compared to the general population.12 Research suggests that for many such individuals the belief system of the Spiritualists provides an explanation for anomalous experiences that might otherwise be distressing. Interpreting the hallucinated voices as a gift rather than as a potential sign of mental illness allows the mediums to live happy and productive lives.

Having said that, it is equally clear that some of those who claim paranormal abilities are deliberate fraudsters. At this point, I would like (with tongue firmly in cheek) to propose French’s Second Law: “The higher the profile of the psychic claimant, the more likely it is that they knowingly use fraudulent techniques.” Sincere but deluded low-profile claimants are typically unable to consistently deliver impressive performances that would convince the majority of their clients that they genuinely possess paranormal powers. They are, however, able to deliver a sufficient number of performances that allow them to just about earn a living (or at least a bit of extra pocket money) that way. The high-profile psychic or medium, in contrast, has to consistently deliver impressive performances on stage or in front of TV cameras. The pressure to resort to trickery is high.

The deliberately fraudulent psychic is unlikely to rely solely on cold reading to practice their dark art. While cold reading can sometimes produce amazingly impressive results, it can also sometimes fail to do so. To guarantee impressive readings, it is best to also use hot reading techniques. Whereas cold reading is the only option for someone who is genuinely a complete stranger, hot reading requires gathering information about your client in advance.

There are numerous ways to achieve this, but there is no doubt that the widespread sharing of personal information via social media has made the fake psychic’s task a lot easier. Another technique widely employed during stage performances is for the fake psychic to have confederates queue up with the genuine audience members as they are waiting to go in, engage them in friendly conversation, and surreptitiously feed any information gleaned back to the psychic before the show begins.

This tendency of fraudulent psychics use information fed to them in advance can sometimes be used against them by skeptics determined to reveal their trickery. For example, psychologist Ciarán O’Keeffe exposed the trickery of the late Derek Acorah by deliberately feeding him false information on numerous occasions.13 O’Keeffe worked as the resident skeptic on the popular ghost-hunting British TV show, Most Haunted. Acorah was the medium who would frequently appear to become possessed by the spirits at the various haunted locations featured. O’Keeffe suspected that the information apparently being psychically channeled by Acorah had in fact been gathered in advance. He proved his point by feeding the medium information about fictional characters to see if Acorah would become “possessed” by them. He did. These characters included a South African jailer named Kreed Kafer (an anagram of “Faker Derek”) and highwayman Rik Eedles (an anagram of “Derek lies”). On a shoot at Craigievar Castle, near Aberdeen, O’Keeffe “made up stories about Richard the Lionheart, a witch, and Richard’s apparition appearing to walk through a wardrobe—the lion, the witch and the wardrobe!”14 Sure enough, Acorah repeated all of these stories. In fact, Richard I had reigned 500 years before the castle was even built.

Ouija Boards and Table-Tilting

Of course, you don’t necessarily need a medium to communicate with the dead. Several decades ago, when I was a final-year undergraduate at the University of Manchester, I lived in a house with five other male students. One of our favorite things to do on returning from the pub on a Friday night was to set up a Ouija board and converse with the spirits of the dead. Well, maybe that’s not strictly accurate. For one thing, only one of us really believed that these sessions might have anything to do with discarnate spirits, and he steadfastly refused to take part. He would scuttle off to his room and we would not see him again until the next morning.

The second inaccuracy is that we did not have a proper Ouija board.15 Instead, we used the approach, beloved of curious teenagers around the globe, of using an upturned wineglass resting on a smooth table. Before the session, we would write all of the letters of the alphabet plus the numbers from zero to nine on scraps of paper and arrange them in a circle on the table. We would then place the upturned wineglass in the center of the circle, and each of us would place one finger on the base of the glass (which now faced upward). Then one of us would solemnly ask, “Is there anybody there?”

Typically, it would take a while for a session to really get going. Initially, the glass, with our fingers still touching it, would appear to move hesitantly, spelling out short answers to our questions, but after a while the movements appeared to become stronger, almost as if “the spirits” were becoming more familiar with the positions of each letter on the board. During a really good session, the glass would whizz from letter to letter, spelling out messages from the Great Beyond.

Now, the obvious nonparanormal explanation for what was going on here is simply that one of us was knowingly pushing the glass around in response to the questions asked of the “spirits.” However, it was noticeable that, during a long session, each of us would on occasion take our fingers off the glass and just sit back and watch, as if to say, “Well, that proves that I am not pushing it.” I cannot really remember now, but I do not think I had a good explanation for what was going on, but I do know that, most of the time at least, I did not think it was communication from beyond the grave.16 We engaged in this activity for entertainment purposes only, often with weird and hilarious results. For example, on one memorable occasion, it looked like contact had been made with “King Michael of Denmark.” We asked him how he died. “Love of toast,” came the reply. Confused, we asked for clarification. The glass slowly spelled out, “Poison in the marmalade.”

In fact, the movement of the glass around the table is best explained in terms of the ideomotor effect. First used in 1852 by William Benjamin Carpenter, the term is defined in the Skeptic’s Dictionary as “the influence of suggestion or expectation on involuntary and unconscious motor behavior.”17 In other words, we really were pushing the glass around the table, we just were not aware that we doing so. It follows, if the explanation in terms of the ideomotor effect is correct, that no meaningful messages would be produced if all sitters were blindfolded—and that is precisely what is found.18

This is the explanation favored by most scientists and virtually all skeptics, who would view the use of Ouija boards as nothing more than harmless fun. But what about claims from fundamentalist Christians (and some self-styled paranormal investigators) that the use of Ouija boards is dangerous and can open the door to powerful and evil supernatural forces? It is easy to scoff at such notions, and, in my personal opinion, fears of that sort are generally unfounded—but not always. If someone is psychologically vulnerable to begin with, messages spelled out by the Ouija board could potentially feed in to other delusional beliefs with disastrous results.

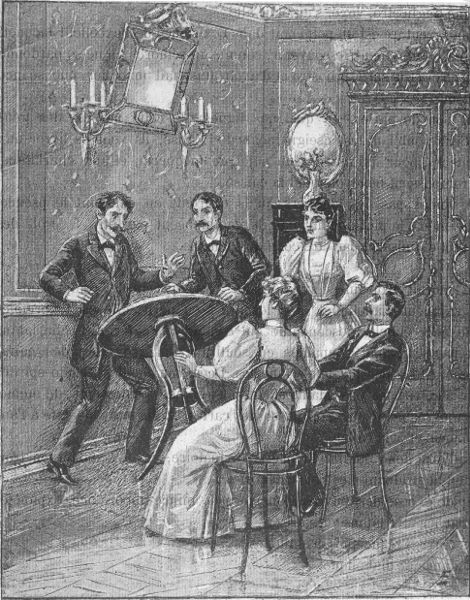

The ideomotor effect provides an explanation for another allegedly paranormal phenomenon, that of table-tilting (also known as table-turning, table-tapping, and table-tipping; figure 4.1). Table-tilting was a craze that caught on in America and Europe at the height of the popularity of séances, back in the Victorian era. It involved having sitters place their hands on a small round wooden table as an alleged means to communicate with spirits. Questions would be put to the spirits, who would respond by making the table move. The movements might consist of nothing more than simple shuddering, but a really good session might result in the table moving quickly around the room.

Table-tilting has a special place in the history of anomalistic psychology because it caught the attention of the great English physicist Michael Faraday (figure 4.2). In 1852, Faraday, with admirable open-mindedness, was so intrigued by the phenomenon that he designed a number of ingenious tests to investigate whether the table really was being moved by some mysterious external force or whether, in fact, those taking part were pushing the table without being aware of it. You can guess what he found.

Figure 4.1

Communicating with the spirits through table-tilting could occasionally get out of hand.

Figure 4.2

The great English scientist Michael Faraday, pictured here giving a lecture at the Royal Institution in London, carried out investigations into the phenomenon of table-tilting.

Electronic Voice Phenomenon

One other means of spirit communication that is particularly popular with many self-styled paranormal investigators is known as the electronic voice phenomenon (EVP). This technique was discovered, if that is the right word, by Swedish artist Friedrich Jürgenson in 1957. He claimed that other human voices were to be found in a recording he had made of his own voice and then, a couple of years later, in a recording he had made of birds singing. He believed these voices to be those of alien life-forms as well as of his deceased mother. However, it was the Latvian psychologist Konstantin Raudive who brought the phenomenon to the attention of a wider public with the publication of his book Breakthrough in 1971.19

The basic technique, as currently employed by numerous amateur paranormal investigation groups, is to leave a recording device in record mode in a reputedly haunted location. Typically, this device will be left running for several hours in, for example, an empty room. It is claimed that when the recording is listened to carefully, voices can be heard. These voices are usually interpreted as being produced by spirits of the dead, but some EVP enthusiasts also entertain the idea that the voices may be those of aliens or even beings from other dimensions.

There is also much variation in the details of how the technique is employed. The recording device is not always left in an empty room. Instead, some investigators prefer to direct questions toward the spirits and then leave a gap of silence in the hope that the response will be recorded. Although no reply is typically heard by those present at the time, it is claimed that clear and coherent replies can be heard when the recording is played back. In the days prior to digital technology, it was claimed that EVP could be recorded from radios not tuned to a particular channel.

Paranormal investigators typically claim that the messages received are very clear and meaningful. There are dozens of websites where you can listen to these messages for yourself, as well as many YouTube videos featuring EVP from both popular paranormal TV series and amateur groups. On the websites, the message is typically displayed on the screen as the audio recording is played. When investigators report their findings, they typically tell the viewer what they think the message is before they play the EVP and often, just for good measure, display it in writing on the screen as the audio clip is repeatedly played.

How can these voice-like sounds be explained if, in fact, they are not being produced by discarnate entities? I think a clue lies in the fact that the recordings fall into two fairly distinct groups. The first set consists of pretty clear recordings of easily discernible messages from what sound like human voices. So the most obvious explanation is that these sounds are, in fact, the voices of living human beings that have been recorded inadvertently. Despite the best efforts of the investigators, it is inevitable that the recording device will occasionally pick up snippets of speech from people who just happen to be within auditory range. Other possibilities, depending on the specific EVP method used (and in which era), include interference from broadcasts and artifacts arising from the technology used (e.g., incomplete erasure of previous recordings).

The second group of EVP clips is much less clear. They are typically very short, poor-quality recordings, often with a lot of background hiss. In fact, it is usually not possible to make out the message unless you read it for yourself or someone tells you. The interpretations given to these vague and ambiguous sounds vary considerably from one person to another. When I discuss EVP in public talks, I like to play examples to the audience without telling them what the message is and ask them to guess. Audience members typically have no idea what the message is. When I tell them what it is supposed to be and play it again, many of them agree that they can now “kind of hear it.” Sometimes I will throw in a trial where I get them to hear exactly the same audio clip in different ways simply by priming them with different messages having a generally similar vowel structure.

Michael Nees and Charlotte Phillips played samples of EVP, actual speech, acoustic noise, and degraded speech to participants who were told either that the experiment was about paranormal EVP or that it was about speech intelligibility without any mention of the paranormal.20 Interestingly, despite the participants generally having quite low levels of belief in the paranormal, they indicated that they could detect more voices in both the EVP and degraded speech trials in the paranormal context. However, when a voice was reported, there was very little agreement between the participants on trials regarding what the voice actually said. As noted by many commentators, EVP samples appear to be nothing more than auditory pareidolia arising from speech-like background noises.21

Some paranormal investigators interpret some of the sounds they hear as nonspeech sounds, such as coughing or even animal noises. One paranormal investigator I know of claimed to have recorded a ghost horse neighing. It had been recorded in a part of a building that used to be a stable. The noise did not sound like a horse to me, but I am no expert so I asked my wife, Anne, and one of my daughters, Alice, to listen to the short clip and tell me what they thought it was. Both were keen horse-riders at the time. Neither of them said it was a horse neighing. In fact, when I suggested that that is what someone thought it was, they dismissed the idea outright.

On another memorable occasion, I was taking part in a TV series called Haunted Homes when apparently a ghostly sneeze was recorded on an EVP recorder belonging to our paranormal investigator, Mark Webb. This took place in a reputedly haunted radio station, Radio Beacon, in the United Kingdom. The recording caused great excitement, as a ghostly sneeze had been reported on many previous occasions in the building. As this was the only time in two series that anything objective had been recorded during one of our investigations, the program makers were keen to make the most of this amazing piece of hard evidence.

I did an interview to camera giving my reaction: “In the case of the sneezing, which Mark actually thought he heard himself last night, he’s played that recording back to me, and I have to say, to me it sounds like something that might be a sneeze but it might be a hundred and one other things as well. And this is a general problem with the EVP, the electronic voice phenomenon, that it’s very, very easy for people to read into those very ambiguous sounds whatever it is that they think they are supposed to be hearing.”

On our second night at that location, I decided to pop to the toilet before filming began on the first floor, near to where the ghostly sneeze had been recorded. As I emerged from the cubicle, Mark was there with a somewhat disgruntled look on his face, pointing at the tiled wall. As I looked toward where he was pointing, the mystery was solved—there on the wall was an automatic air-freshener. Within a couple of minutes, sure enough, it operated, making a noise that sounded just like a sneeze. Mark and I both did interviews to camera the next morning, explaining that we now knew what the noise was, and it was definitely not a ghost. When the program was actually broadcast, a lot of coverage was devoted to the ghostly sneeze. Sadly, however, the editors did not appear to have enough time to include our explanation in the program.

Before We Move On . . .

Many years ago, I was lying on the bottom bunk bed with my daughter Kat, about six years old at the time, lying above me in the top bunk. (I can’t remember the details, but I assume her younger sister, Alice, must have been poorly and sleeping with her mum.) All of a sudden, Kat let out a heart-wrenching sob. Panicked, I shot out of bed and asked her what was wrong. “I don’t want to die,” she wailed.

Trying my best to be reassuring, I said, “You don’t need to worry about that. You’re young, you’ve got your whole life ahead of you.”

“Yes,” she replied. “But I will die, won’t I?”

Desperate, I found myself saying, “Well, some people think that when you die you go to heaven . . .”

Interrupting me, she tearfully said, “Yes, but you don’t, do you?”

Sometimes it’s hard to be an atheist.

I have mainly concentrated in the last two chapters on anomalous experiences such as sleep paralysis and various cognitive biases that may be associated with belief in and experience of ghosts. But we should not neglect emotional and motivational factors. Very few people can honestly claim not to be frightened by the idea of their own mortality—or, perhaps even more so, the mortality of their loved ones. Most of us want to believe in some form of life after death, an idea that is an integral part of the world’s major religions. Most of us would like the death of our physical bodies to not mean the end of our subjective consciousness. If there is an afterlife, then there must be something more to us than brains encased in meat machines—each of us must have a soul or a spirit, call it what you will.

However, if that it is indeed the case, it opens up the possibility that sometimes those souls may on occasion fail to move on to heaven (or wherever else they are supposed to go) and instead hang around on the earthly plane. Thus, even though many of us might find the idea of ghosts scary, there is no denying that evidence of ghosts supports the idea of an afterlife.

Confirmation bias is a ubiquitous cognitive bias. It affects everyone. It refers to the fact that we are all more impressed by evidence that appears to support what we would like to be true or that we already believe to be true. We tend to notice more of such evidence compared to evidence that contradicts our belief. We find it more compelling. We think of reasons why the contradictory evidence can be ignored.

Given the strength of our primordial existential fear regarding our own mortality, it is no surprise that so many people find even the weakest evidence for life after death to be so convincing.