10

Skeptical Inquiries

The main focus of anomalistic psychology is on trying to produce and empirically test nonparanormal explanations for ostensibly paranormal phenomena, as the previous chapters illustrate. It must be always borne in mind, however, that the notion that paranormal forces do not exist is itself not proven. Indeed, logically it is one of those negative statements that can never be proven. Even if paranormal forces have not been shown to exist after well over a century of systematic research, it is always possible that proof of their existence will be found at some point in the future.

The idea that psi does not exist is simply a working hypothesis guiding research in anomalistic psychology, which, by its very nature, could never be proven. Having said that, the more ostensibly paranormal phenomena that anomalistic psychology can explain, the less need there is to entertain paranormal hypotheses. In light of the fact that we recognize the theoretical possibility that psi just might exist, however unlikely we may judge this to be, members of the Anomalistic Psychology Research Unit at Goldsmiths (APRU) put considerable time and effort into directly testing psychic claims. This chapter and the next describe some of these tests, most of which were carried out as part of television documentaries and have never appeared in print before.

Britain’s Psychic Challenge

Britain’s Psychic Challenge is a TV series that was broadcast in the United Kingdom by Channel 5 and presented by Trisha Goddard. The main series was broadcast in 2006, but this was preceded in December 2005 by a special one-off program to introduce the series. The idea was that the series would be a kind of X Factor for psychics. Each week, a group of psychics would be set various tasks to perform using their claimed psychic abilities, and at the end of each program, the worst-performing psychic would leave the competition. Eight psychics were selected from almost 2,000 applicants to take part in the series. In the final program, the three remaining psychics competed against each other, and ultimately one was declared the overall winner—in some people’s eyes, this was to be officially declared Britain’s top psychic!

The psychics’ performances were discussed and judged by a “panel of skeptics” consisting of myself, Philip Escoffey, and Jackie Malton. Philip is a professional mentalist and conjurer.1 Jackie is a former senior police officer and now works as a TV script consultant. Her police career provided the inspiration for the fictional DCI Jane Tennison in the hugely successful TV series Prime Suspect written by Lynda La Plante and starring Helen Mirren. I enjoyed working with both Philip and Jackie, but I think it is fair to say that Jackie turned out to be not much of a skeptic as the series progressed.

Needless to say, taking part in this series raised concerns on my part about being a token skeptic whose appearance might lend some legitimacy to a venture that perhaps did not deserve it. After all, I knew in advance that at the end of the series I would be partly responsible for declaring one of the contestants to be Britain’s best psychic. In the end, though, I decided to do the program for a number of reasons. First, because I reasoned that if I did not take on the role, someone else would; second, because I believe that it is important for the views of an informed skeptic to be included in such programs; third, because I needed the money; and finally, because I anticipated, correctly as it turned out, that it would be fun.

From the outset, it was clear that this program was going to present Philip and me with something of a dilemma. Just like Haunted Homes, its intended target audience would be believers, hungry for evidence of amazing abilities that defied conventional explanation. If the tests had been designed by Philip and me, combining his knowledge of the deceptive art of mentalism with my expertise in parapsychological research, we can be pretty certain that very few of the psychics would have passed any of the tests. At least, that would seem to be a fair conclusion based on my many years of carrying out such tests under well-controlled conditions. It is unlikely that the show would have retained its intended audience if, week after week, the psychics had all failed every test set for them. So, as you might have guessed, the tests were not designed by us. In general, they were deliberately designed to ensure that, even on the basis of guesswork alone, there would be some successes, and the conditions were far from properly controlled.

It should be noted that the tests devised for the program were also problematic from the psychics’ point of view insofar as they were not designed around the specific claims of those particular psychics. If a psychic claimant insists that they are able to divine the contents of sealed envelopes, it is clearly inappropriate to test them by, say, asking them to psychically determine which of several women are pregnant. When members of the APRU put psychic claimants to the test, great care is always taken to design the test around the specific claims being made. If this is not done, failure on the test tells us nothing. In fact, we routinely get claimants to sign a document in advance stating that the test is a fair test of their alleged abilities. When the claimants on Britain’s Psychic Challenge failed particular tests, as they often did, they were usually justified in simply shrugging and pointing out that they never claimed to have the specific psychic abilities required to pass that particular test.

Over the six episodes broadcast in 2006, a total of twenty different tests were set for the psychics. Given that there were eight psychics in the first episode that were whittled down to three in the final episode, this means that there were 118 opportunities for the psychics to demonstrate their powers. Unfortunately, this rarely happened.

Given the large number of tests set for the psychics, space limitations preclude a detailed analysis of each and every one of them, but a few general observations are in order. Some of the tests did allow a definite success or failure result. This would obviously be a very good thing if the test itself was well designed and well controlled, but sadly this was virtually never the case. To give an example, one of the tests set for six psychics in the one-off introductory program was to see if they could identify in which of fifty cars in a parking lot was a volunteer hidden in the trunk. If this test had been designed and carried out properly, each psychic would have only a one in fifty chance of being right on the basis of guesswork alone. Should we therefore be impressed that three of the six psychics actually identified the correct vehicle?

The short answer is no. There were a number of serious flaws with this test. For example, the volunteer was allowed to choose which trunk he wanted to hide in. The fifty cars varied considerably in size, color, position, and so on. There would be an understandable desire to choose a car with a reasonably spacious trunk that was not parked in a position that would make it difficult to get in and out of. In an ideal world, the test would involve fifty identical cars, but at the very least fifty similar cars should have been used, all parked in such a way that the trunks were easily accessible. Furthermore, the car that the volunteer was to hide in should have been chosen at random, and all of the other cars should have had weights equivalent to the weight of the volunteer in order to ensure that one car did not stand out because its back end was lower than its front end in comparison to others.

Another major flaw was one that undermined the validity of many of the other tests in the series. No attempt was made to use a double-blind methodology. In any test involving selecting the correct target from a number of potential targets, it is not enough that the person being tested has no prior knowledge of the right answer; it is essential that no one in the vicinity of the test has such knowledge. In the case of the “body in the trunk” test, it was clear that the camera crew, as well as Jackie Malton, who was supervising the test, knew where the volunteer was hidden. This raises the very real possibility of the crew giving unintentional cues as to the target’s location. For example, a camera operator may well zoom in when the psychic is near the correct car. On at least one trial, Jackie was standing right next to the target car as she encouraged the psychic to make a choice!

Given how poorly controlled most of the tests were, the psychics still managed to perform remarkably poorly on most of them. For example, when asked to identify the two women who were pregnant from a group of ten, none of the eight psychics identified both women correctly, and five got neither of them right. Their total score of three was the same as that obtained by a group of eight, presumably nonpsychic, student volunteers and did not exceed what would be expected on the basis of chance alone.

Many of the other tests were even worse insofar as it was virtually impossible to determine just how successful or unsuccessful the psychics had been. These were tests where the possibility of cold reading, either intentional or unintentional, had simply not been taken into account. Once again, a good example was featured in the one-off introductory program. The program was broadcast from Knebworth House, an English country house in Hertfordshire. The residents of the house are screenwriter Henry Lytton-Cobbold and his family. Two of Henry’s ancestors had been killed in tragic circumstances: Antony Lytton-Cobbold died in a plane crash in the 1930s, and his brother, John, was killed during a tank battle in the Second World War. The three psychics who were successful in the “body in the trunk” challenge were handed two envelopes, each containing a photograph of one of the brothers. Their task was to glean information about the two individuals using their psychic ability.

Often in programs that include psychic readings, the reading is heavily edited to include only those parts of the reading that could be deemed, sometimes with a little imagination and interpretation, to be hits. In this case, even careful editing could not produce this impression. This test, along with numerous other similar tests throughout the series, did provide the viewers with nice illustrations of cold reading in action, though. For example, consider this exchange between Henry Lytton-Cobbold and one of the psychics, Amanda Hart:

AH: What I’m picking up so far is a boat. It’s got no sails, but it’s got lots of masts. There’s lots of—all I can see is lots of masts and crisscrossing. It’s quite like—I’ve got a little boat.

HL-C: Is it definitely a boat, might it be an airplane?

AH: It’s not that clear. It’s like a man with a helmet but it’s made of, almost, leather—and goggles.

This is a very clear example of the sitter trying hard to fit the utterances of the psychic to what they know to be the facts and, in the process, steering the psychic in the right direction. Elsewhere in this and other readings throughout the series, all of the standard tricks of cold reading, whether intentional or unintentional, can be seen in action.

Dowsing with Dawkins

In 2006, I was contacted by a researcher working on a two-part documentary series titled The Enemies of Reason, which was to be presented by the eminent evolutionary biologist and author Professor Richard Dawkins. The researcher wanted to know if we were carrying out any research projects that might be suitable for inclusion in the program. As it happened, we were planning on a double-blind test of dowsing at the British Association Festival of Science 2006 that was to be held in Norwich that year. Following some discussion, it was decided that our test was indeed suitable for inclusion in the program, which was broadcast in the United Kingdom in 2007 on Channel 4.

Dowsing, as defined by Ray Hyman, is “the practice of finding hidden objects or substances with the aid of a forked twig, metal rods, or some other device that indicates the location of the desired target by its movement.”2 One example of dowsing is the alleged ability to locate a hidden object using a forked rod. A forked stick (referred to as the dowsing rod, dowsing stick, or divining rod) is the most commonly used device, but dowsing rods can be made of almost any other material, including iron and steel.3 Although the rod may vary in material and shape, it is almost always forked and very light in weight.4

The standard method is to hold the dowsing rod in front of the body, arms outstretched with palms facing upward and one fork in each hand, so that the elbows are inward against the body.5 Dowsing can also be performed using L-shaped metal rods, one held in each hand (see figure 10.1). The rods are held in such a way that the long arms of the L point forward in parallel with each other. The belief is that as the dowser approaches the target object or substance, the dowsing rods will cross. Normally, dowsing is conducted outdoors in open spaces, but it can also be practiced indoors. Some dowsers even claim to be able to search for an object not in the immediate vicinity by dowsing over a map. Map dowsers typically use pendulums rather than dowsing rods.

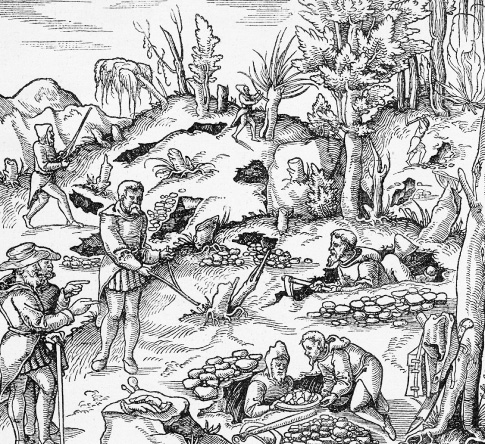

The origin of dowsing is debatable, as is its original purpose. However, most researchers now generally concur that dowsing began, and then became prominent, in sixteenth-century Europe, where it was used by German and English miners to locate underground metal (figure 10.1). Originally used to locate both metal and underground water, dowsing is now used to locate almost anything, including lost objects, missing persons, precious metals, and the flow of electrical current and is even used as a decision-making tool. Some paranormal investigators claim to be able to communicate with spirits using dowsing rods.

Figure 10.1

The author trying his hand at dowsing (without success). Photograph courtesy of Valerie Heap.

Figure 10.2

Woodcut by Georgius Agricola, dated 1556, illustrating the use of dowsing to locate deposits.

Even amongst dowsers themselves, there is considerable debate regarding the question of how dowsing might work. Some practitioners are convinced that when the dowsing rods move it is because some external force has moved them. Others accept that the movement is caused by muscular activity on the part of the dowser, even if those muscular movements are unconscious, but they may still believe that the fact that the rods moved precisely when they did is because the dowser had obtained knowledge of the target location by psychic means.

Not surprisingly, there are many dowsers who embrace a host of other New Age beliefs. But interestingly there is a sizeable minority who very much want to distance themselves from what they would deem to be such ‘woo woo’ ideas. These are people who very much see themselves as rationalists and strong supporters of science. I suspect they have come to believe in dowsing on the simple basis of trying it out—and being surprised to experience what appeared to them to be the movement of their chosen dowsing device of its own accord. Rather than asking whether there might be a psychological explanation for this phenomenon, they immediately assume that there is some real physical force at work, perhaps electromagnetism, that could potentially be measured objectively.

The big question is, of course, does dowsing actually work? Anecdotal evidence and field studies are often cited by those arguing in support of the validity of dowsing.6 In contrast, whenever dowsing is tested under properly controlled conditions it appears to be no more effective than pure guesswork.7 Critics of dowsing point out that the apparently positive results obtained in field studies may be based upon the dowsers, either consciously or unconsciously, making use of sensory cues available in the environment. For example, if dowsing is being used to locate underground water, the lie of the land and patterns of vegetation may supply such cues.

We wanted to keep our test as simple and straightforward as possible. Different dowsers, as stated, make very different claims. Although some dowsers insist that dowsing can only be used to locate flowing water, many others claim that dowsing can be used to locate pretty much anything. Our test investigated whether dowsing could be used to identify which of six plastic boxes contained a bottle of water, the others all containing bottles of sand. This test was certainly not rocket science, as the saying goes, but even so it took a lot of setting up and I am grateful to the Society for Psychical Research for providing a small grant to pay for materials and to my trusty voluntary research assistant, Mark Williams, for obtaining all of the required equipment. Thanks are also due to Elaine Beattie and Rosie Bunton-Stasyshyn for their assistance in running the formal double-blind test.

We had recruited eight experienced dowsers for our test, four male and four female, aged between 47 and 76. The number of years of dowsing experience ranged between ten and fifty-six years. All participants considered themselves to be amateurs with the exception of one who was semi-professional. Seven of the participants believed that the forces responsible for moving the rods were grounded in natural science (e.g., conductivity, electromagnetic fields, energy fields, gravity), while one participant believed that God is responsible for moving the rods.

The test was conducted outdoors in a tented area with an audience present and the whole test was recorded not only by us but also by the film crew working with Richard Dawkins.8 Each dowser was allowed to walk around the area to establish clear spots for the location of containers and dead spots where their rods moved indicating ‘interference.’ Any dead spots located were clearly marked and containers were not subsequently laid on these areas.

The dowsers all used their own dowsing rods (or, in one case, their own pendulum). They were asked to check the conditions in order to confirm that their dowsing rods were responding as they normally did. Each dowser was shown a bottle of water and a bottle of sand and asked to hold their rods above each bottle. As the dowsers would expect, the rods crossed above the water bottle but not above the bottle containing sand. They were then asked to repeat this procedure with the bottles inside the plastic boxes with the lids closed. Once again, when the rods were above the box that the dowser knew contained a bottle of water, the rods crossed. Over the other box, there was no movement of the rods. Having satisfied themselves that the conditions of the test were fair, each participant was led away from the test site to a holding area and required to sign a consent form agreeing to take part in the formal test.

Each dowser was then required to take part in six test trials. In accordance with the rules of the tests, all were informed that any one of them scoring four or more hits out of the six trials would be deemed to have passed the test. There was just less than one chance in a hundred that any individual dowser would obtain a score this high or higher purely on the basis of guesswork alone. For each block of trials, the test area was closed off completely from everyone except Rosie. She determined which randomly determined container would hold the bottle of water for each trial, placed the bottles of water and sand as required, and then removed herself completely from the test site. There was thus no opportunity for any information to be conveyed to the dowsers or to anyone else regarding the location of the hidden water bottles. This is what is known as a double-blind testing procedure where no one present during testing knows the correct answer until testing has been completed. This ensures that no one can give any clues to the dowser, either intentionally or unintentionally.

When it was their turn to be tested, each dowser entered the test site and moved up and down the rows of containers, dowsing each one. They were allowed to take as much time as they liked. When they felt they had identified the location of the bottle of water, I placed a marker next to the chosen container. At the end of each individual trial for each dowser, they watched as the containers were opened and they could see how well (or badly) they had done. Of our eight dowsers, two failed to identify any of the containers containing a bottle of water, four got one right, and two got two right. The overall average number of hits was one out of six, exactly the outcome expected on the basis of pure guesswork.

Despite not passing the test, however, all of our dowsers remained confident in their ability to dowse successfully. Their lack of success on our test did not appear to shake their belief at all. They offered a range of reasons as to why they felt their attempts to locate the water were unsuccessful. Four of them suggested that their inability to locate the water was due to it being situated above ground and suggested that they would have been more successful dowsing for moving water below ground level. Two suggested that the plastic containers were interfering with the electrical signals transmitted from the water. One participant felt that their lack of success was due to the fact that God did not want them to find the water on this occasion. However, this dowser decided some time later that he had simply not been asking God the right question. Another dowser felt that there were too many dowsers present and hence the signals from the water could not be detected. This type of post hoc reasoning is common when dowsers fail a controlled scientific test. Our dowsers appeared to be genuinely surprised at their results but nevertheless remained steadfast in their conviction that dowsing works.

The dowsers all seemed to forget that in the pre-test checks, the dowsing rods had shown exactly the expected responses when held over a bottle of water and a bottle of sand, whether in full view or inside a container. Of course, the difference between these checks and the formal double-blind test trials was that the dowsers knew the locations of the water and the sand in the pre-test checks and the rods behaved in accordance with their expectations. The explanation of the movement of the rods was thus due to our old friend, the ideomotor effect, as described in Chapter 4.

Despite the lack of good quality evidence from well controlled studies, many people are still absolutely convinced that dowsing does indeed work, including such no-nonsense people as those who run water companies in the UK. Science blogger Sally Le Page was shocked to discover that no less than ten out of twelve major water companies in the UK confirmed that, in 2017, they were still making use of dowsing to locate leaks in water pipes.9 Her findings were reported on in the Guardian by Matthew Weaver, followed a week later by an influx of angry letters from supporters of dowsing defending the practice.10 The Reverend Martin J. Smith of Wilmslow, Cheshire, was typical in insisting that the reason the water companies and others use dowsing is simple: “it works, it is replicable and it is independently verifiable.” The good reverend and the other angry correspondents are almost certainly mistaken as the results of numerous well-controlled tests of dowsing, including our own, convincingly demonstrate.

The Baby Mind Reader

In 2006, the future was looking very bright for psychic Derek Ogilvie.11 In April that year, he had published a book with the title, The Baby Mind Reader: Amazing Psychic Stories from the Man Who Can Read Babies’ Minds.12 A couple of months later, his own series launched on Channel 5 in the UK.

Derek’s unique selling point as a psychic was his claim that he had an amazing ability to read the minds of very young children, even including pre-verbal babies. Whereas you might assume that babies would rarely be thinking about much other than “I’m hungry” or “Whoops, I’ve just pooed myself!,” it turns out, according to Derek, that they are all too aware of many other aspects of family life including marital problems, employment issues, even issues relating to the family car or home. Who knew?

In 2007, Derek agreed to take part in a further documentary to be broadcast on Channel Five, this time a one-off in the Extraordinary People series. The title of this programme was The Million Dollar Mind Reader, referring to the fact that Derek was to be tested by not only members of the APRU but also by the one and only James Randi. If Derek passed the test set by Randi, he would receive a cool one million dollars (if he passed our test, he would receive a nice cup of tea and a biscuit—which he could also have even if he did not pass the test).13

In his 2006 series, Derek would typically give his reading for babies and young children in the presence of their parents. The parents often expressed amazement at the accuracy of his readings. The problem here will by now no doubt be obvious to the reader. No attempt was made to rule out the possibility that Derek was using, either intentionally or unintentionally, standard cold reading techniques, let alone hot reading. The correct way to test Derek was pretty obvious. He should do readings for a number of children of whom he had no prior knowledge whatsoever without the parents (or anyone else who knew them) being present at the time. Once all readings had been transcribed, the parents would then be invited back and asked to choose the reading that they felt had been done for their child. If Derek could really do what he claimed he could do, there should be one reading that stood out as containing lots of specific and accurate information about that particular family’s circumstances. I was told that Derek referred to our test, as he was being driven down to Goldsmiths to be tested, as “a piece of piss,” a charming British expression which translates as “easy peasy.”

With the assistance of the television production company that was making the documentary, Krissy Wilson and I set up the test as described. On the day of testing, each of six children (aged between 15 months and 2.5 years) was brought, one by one, into the testing room by a registered child minder who remained throughout. Typically, Derek would walk around as he did his readings, sometimes gesticulating wildly. Krissy and I watched proceedings from behind a one-way mirror. Of course, we had no idea as the readings were being given for the children whether they were accurate or not but something interesting did happen at one point. Derek appeared to forget that he was supposed to be giving a reading for the child and started giving a reading for the child minder. She, for one, was impressed with that reading—but, of course, cold reading was one obvious explanation. To pass our test, four or more parents would have to pick the correct reading for their child from the six that they would be given. Purely on the basis of chance alone, such a result would occur less than one time in a hundred.

It was a long day’s filming but the real hard work was just about to begin for one poor researcher who had the task of preparing transcripts of Derek’s readings. It was originally felt that the most efficient approach would be for the transcripts to consist of a summary of the most important points made in each reading but Derek was very unhappy with this idea. When he saw the original summaries, he felt that too much information had been edited out. The actual transcripts used for the judging task thus ended up being rather lengthy, averaging over 500 words each. Certain themes tended to recur in the readings including health issues of the child and parents, relationship and emotional issues, and problems relating to the state of the family home and car.

The level of alleged knowledge regarding the family car was sometimes incredibly detailed, as this extract from the reading given for a 2.5-year-old girl demonstrates:

The child was telling me about a car. The following could be associated with one or two cars. One car has or had a wheel or tyre problem on the front driver’s side; this is associated with a dark colour car. There is also a scratch or sticker on this car on the lower part of the windscreen on the driver’s side. There has also been problems with that car with the rear, driver’s side, tyre and a brake problem. On the inside of the passenger seat there is a mark or tear beside the handbrake. A door handle doesn’t seem to be working all that well either. There is also a noisy exhaust. The child mentioned that there is an issue with getting a car into first gear with a parent.

So, how well did Derek do? By chance, we would expect one reading out of six to be chosen correctly—and that was exactly the result obtained. Derek was extremely upset at this outcome, proclaiming through his tears, “Well, that’s it then! My career is over!” I tried to reassure him that the results of our test would not have any effect on his fans whatsoever.

The next day, Derek set off for Florida to be tested by Randi, in the hope that he would be returning home one million dollars wealthier. Sadly for him, he completely failed that test as well. One might have hoped that his complete failure on two fair tests of his ability would be enough for viewers to draw their own conclusions but the programme-makers apparently felt the need to provide at least a crumb of comfort for the true believers.

In the final part of the programme, Derek had his EEG recorded by Dr Gerald Gluck while attempting a psychic link with another toddler. Dr Gluck opined that Derek’s EEG was very unusual, leaving the more gullible viewer with the distinct impression that maybe he was psychic after all. Even if Dr Gluck’s interpretation of Derek’s EEG was accurate, such a conclusion would be, of course, completely unjustified. The EEG recorded was simply a record of Derek’s brain activity when he was trying to be psychic, not when he was actually being psychic. We can be pretty sure that if the reading produced while Derek’s EEG was being recorded had been at all accurate, the narrator of the documentary would have made a point of saying so. It is also worth noting that Dr Gluck was himself a strong believer in various New Age ideas, even proclaiming himself to be an “energy healer.”

Putting the Claims to the Test

In 2008, Mrs Patricia Putt contacted the James Randi Educational Foundation (JREF) asking if she could be tested with a view to claiming Randi’s million-dollar prize. In common with other mediums, Pat believed that she could communicate with the spirits of the dead and, in this way, glean information about complete strangers without having to speak to them or even see them. Pat believed herself to be the reincarnation of an ancient Egyptian by the name of Ankhara, a discovery that she had made as a result of hypnotic regression. She had worked for many years as a professional psychic.

Before Pat could try for the million dollars in Florida, JREF required her to pass a preliminary test in the UK. Richard Wiseman and I were asked to carry out this preliminary test and we agreed to do so. Once again, the basic idea behind the test was very simple. Pat would be asked to produce ten readings for ten complete strangers using only her psychic powers. Those ten readings would then be presented in random order to each of the individuals for whom the readings had been done and they would be asked to pick the reading that they believed was done specifically for them. If Pat could really do what she claimed she could do, there should be one reading in the collection that stood out from the rest for each volunteer participant as containing lots of accurate, specific details. If five or more of the volunteers chose the correct reading, Pat would be deemed to have passed the preliminary test.

An initial protocol had already been worked out between Pat and members of JREF before Richard and I were contacted and a further round of tweaking the protocol took place after we were contacted. Wherever possible, all reasonable requests from claimants in tests such as these are granted, provided that doing so does not compromise experimental control. For example, Pat asked if the volunteer sitters could read a short pre-specified passage of text as she believed that “the Spirit enters and makes contact through the sound of the sitter’s voice.” Her request was granted. As always, it was crucially important that the claimant was happy with the agreed test conditions. Pat signed a statement to this effect prior to being tested.

Although the basic idea behind this test was very simple, there were many methodological considerations that needed to be taken into account that might not be so obvious. For example, as noted elsewhere:

Mrs Putt agreed not to include in her readings anything that might give an indication of the position of the reading in the series (e.g. “Feeling more confident with this one” would indicate that this could not possibly be the reading for the first volunteer). She also agreed not to make any reference to events that she might overhear outside the testing area (e.g. had there been the sound of children playing during one reading and reference was made to “happy children” in the reading itself). She agreed that all of the participants could be selected from the same ethnic group (Caucasian), be of the same gender (female), and within a restricted age range (18–30). This is because a person’s voice gives away much information regarding such factors.14

The actual test took place in May 2009 (with the invaluable assistance of volunteer helpers Panka Juhasz, James Munroe, Suzanne Barbieri, and Fabio Tartarini). Each volunteer sitter was led into the testing room by myself and seated on a chair facing the wall. Only then was Pat brought in by Richard and seated at a desk at the opposite end of the room, where she quietly wrote her readings down. When she had finished her reading, Richard led her away and the next trial began. One aspect of the protocol agreed between Pat and JREF before Richard and I got involved did give the proceedings a slightly surreal appearance. In order to ensure that Pat could not pick up any clues about the volunteer sitters from their appearance, each one wore a ski mask, wraparound sunglasses, white socks, and an oversized graduation gown.

Once all of the readings had been completed, all of our volunteer sitters returned and were handed a booklet containing the complete set of ten readings, each in a different random order. They read the set of transcripts carefully and selected the one that they felt was most applicable to themselves. Sadly for her, Pat did not get a score of five or more correct. By chance, one would expect one correct hit out of ten purely on the basis of guesswork but Pat did not even manage that. Not one of the sitters chose the actual reading that had been done for them.

Initially, Pat’s reaction to her failure on the test appeared to be refreshingly different from what we had expected. Instead of coming up with excuses for her failure and deciding that the test was not fair after all, she simply declared herself “gobsmacked” and accepted the result. Unfortunately, within a day or two she had changed her mind. As she wrote in an email to JREF, “With them [the volunteers] being bound from head to foot like black mummies, they themselves felt tied so were not really free to link with Spirit making my work a great deal more difficult.”15 In fact, no one was “bound” and Pat did not speak to the volunteers at any point. Any knowledge of how they felt during the test must, one assumes, have been obtained psychically.

In addition to claiming that no one could be expected to get any hits in this test because of the conditions of testing, Pat also went on to argue that, in fact, she had hits on every trial. In a comment on Richard’s blog, she wrote, “with hindsight I realised that every girl had accepted each and every message that I had written down not one had been discarded, not one thrown away each and every one of the ten girls had gone away with something to me this makes a total of 10 out of 10.”16 Of course, this entirely misses the point that each sitter was required by the protocol to choose one reading from the ten as the one most applicable to themselves even if they felt that none of them was particularly applicable!

Despite feeling, in hindsight, that this test had not been fair after all, Pat did volunteer to be tested again in 2012. Along with Kim Whitton, a spiritual medium and healer with 15 years’ experience, Pat had responded to a challenge issued by myself, science writer Simon Singh, and Michael Marshall of the Merseyside Skeptics Society. We presented our Halloween Challenge as an opportunity for psychics to prove to the world that they really did possess powers that defied explanation in terms of conventional science.17 After all, if they could really do so, this would be an amazing breakthrough for science—perhaps a Nobel Prize or two was within reach? Unfortunately, all of the British high-earning celebrity psychics (including Sally Morgan, Colin Fry, Gordon Smith, and Derek Acorah) whom we invited to take part flatly refused to accept the challenge, but Pat and Kim were willing to step up to the plate.

This test took place at Goldsmiths on October 21, 2012 and was similar in design to the test that Pat had failed in 2009. Once again, our psychics would do readings for a number of complete strangers without seeing them or communicating with them in any way. Our volunteer sitters would then be required to rate each reading for accuracy on a scale from 1 to 10 and to choose the one reading that they felt best described them. Because we were testing two psychics on the same day, we limited the number of volunteer sitters to five. To be deemed to have officially passed the test, all five sitters would have to choose the reading that had been done specifically for them.18

There were a few changes made to the protocol used in the 2009 test. Rather than having our sitters wear the strange outfits worn on the previous occasion, we simply had them sit behind a specially constructed screen. During their reading, they were asked to think about the sort of issues that they might expect a psychic to tell them about. As usual, our psychics signed a statement in advance of the test confirming that they believed it was a fair test of their claimed ability. In addition, they were asked after each reading to indicate their level of confidence that the sitter would be able to recognize herself in that reading. On a 7-point scale (where 7 = totally confident), Kim gave an average rating across all sitters of 5.2 and Pat’s average was 5.8.

Here is one of the readings produced by Kim (presented with the sitter’s permission):

Affectionate, touchy-feely sort of person. Can’t sleep well at night, all sorts of thoughts running through my head. Badminton, tennis. Wants children. Not yet, too young. Glasgow is an important place. Singing and dancing. Would like to develop performance skills. Collecting old photos of places I’ve been to. Individual likes and dislikes—laws and government, not good. Learn to get along together better would be a good start. Can’t get him out of my head. I wish we could be together. Sometimes pain in leg. Like things with salt not sugar. Dutch ancestry? Optimistic and open-minded. Want to get university degree. Living in London enjoyed very much. September is an important month. Help in canteen sometimes. Brother in Holland at home. I can get into paints and crayons. Birthday November. I enjoy winter months. Have many friends here in London. Want to go home soon to see family. Wants to go to South America.

Psychics often have their own unique style, as we can see in this reading where Kim frequently adopts a first-person perspective as though actually inside the sitter’s mind. The reading above was rated as 8 out of 10 by the sitter, who gave ratings of 3 or less for the other four readings. She acknowledged that some of it was inaccurate (for example, the Dutch ancestry) and some of the comments were pretty safe bets (for example, living in London), but this looked like a pretty impressive hit.

Unfortunately, it was Kim’s only hit, perhaps suggesting that even the hits in this reading were based on nothing more than lucky guesses. Overall, Kim’s target readings were on average rated as 3.2 out of 10 by the sitters, compared to 2.4 for the nontarget readings. The difference was not statistically significant. None of our sitters chose the correct reading from those done by Pat. In fact, for Pat the nontarget readings had a higher mean accuracy rating (4.2) than the target readings (3.2). Once again, the results of our test had failed to produce any compelling evidence that psychics really do have the amazing abilities that they claim to have.

Skeptics are often accused of being closed-minded and afraid of accepting the evidence that their critics believe provides overwhelming proof that paranormal powers are real. Those making such criticisms have typically devoted little or no time to directly testing paranormal claims for themselves. Given the considerable amount of time, effort, and resources that I have put into directly testing paranormal claims for myself, I hope the reader understands why I find it a little bit annoying when such criticism is directed my way.