Epilogue: The Limits of Skepticism

I taught a module on anomalistic psychology to students at Goldsmiths for many years. I would always inform students at the outset that I could, if I so chose, give them a twenty-hour lecture course that would convince them that psi really existed. I was familiar enough with the strongest evidence in support of paranormal claims to be confident that I could do that. Presenting that evidence alone, with no critical analysis, would probably have been enough to convince any reasonable person that at least some phenomena are indeed genuinely paranormal. Instead of doing that, however, I would present my reasons for not being persuaded by such evidence and spend the majority of my time in those lectures exploring possible nonparanormal explanations for such phenomena.

I would also point out that even book-length reviews of parapsychology written by well-informed commentators could sometimes come to diametrically opposed conclusions. For example, here are the words of Dean Radin, a vocal proponent of paranormal claims:

the effects observed in a thousand psi experiments are not due to chance, selective reporting, variations in experimental quality, or design flaws. They’ve been independently replicated by competent, conventionally trained scientists at well-known academic, industrial, and government-supported laboratories worldwide for more than a century.1

In contrast, psychologist David Marks, an equally vocal critic of parapsychology concluded, after reviewing seven areas of parapsychological research, “My own beliefs are as they are—toward the extreme of disbelief—because the evidence as I see it warrants nothing more.”2

My own position was and is somewhere in between these two extremes, although definitely more on the skeptical side. I pretty much agree with the conclusion drawn by parapsychologists Harvey J. Irwin and Caroline Watt at the end of their book-length review:

as far as spontaneous cases are concerned it seems likely that there are numerous instances of self-deception, delusion, and even fraud. Some of the empirical literature likewise might be attributable to shoddy experimental procedures and to fraudulent manipulation of data. Be this as it may, there is sound phenomenological evidence of parapsychological experiences and experimental evidence of anomalous events too, and to this extent behavioral scientists ethically are obliged to encourage the investigation of these phenomena rather than dismissing them out of hand. If all of the phenomena do prove to be explicable within conventional principles of mainstream psychology surely that is something worth knowing . . . ; and if just one of the phenomena should be found to demand a revision or an expansion of contemporary psychological principles, how enriched behavioral science would be.3

The Borderlands of Science

In chapter 1, I argued that the oft-stated maxim that you “cannot prove a negative” is simply wrong as a generalization but true with respect to some specific statements, including “psi does not exist.” Logically, it is always possible that convincing proof of the existence of psi will be produced at some future date; for that reason, I have always supported the efforts of experimental parapsychologists engaged in efforts to produce high-quality evidence in support of the psi hypothesis.

Researchers make decisions regarding which topics to investigate based on a host of factors, including their own interests and expertise, the availability of resources to support their research, the interest of the wider scientific community and the general public in their chosen topics, and potential practical benefits produced by their efforts. I have long felt that investigating possible nonparanormal explanations for ostensibly paranormal events was more likely to be fruitful than directly attempting to test the psi hypothesis. I have allocated my research efforts accordingly. However, for me an important part of proper skepticism is to always be open to the possibility that you may be wrong, and therefore I have always devoted some time to directly testing paranormal claims, as described in previous chapters.

At the time of writing, I am engaged in an interesting investigation aimed at testing the hypothesis that lucid dreams may sometimes be precognitive. A lucid dream is one in which the dreamer becomes aware that they are dreaming during the dream itself. In some cases, the dreamer may even be able to exert a degree of control over what happens in the dream. Some people who have never had a lucid dream find it hard to believe that lucid dreaming is a genuine phenomenon, but there is no doubt that it is, as shown by numerous well-controlled studies from sleep laboratories.4

This particular investigation came about when I was contacted by an artist named Dave Green. Dave’s unique selling point is that he creates his pictures while in the lucid state and then recreates them once he wakes up. Dave’s website includes a short video explaining the process. In his words:

The dream begins with me separating from my body. Now this is a lucid dream so I know what I need to do. I go over to my desk. I grab a dream pen and a dream piece of paper and I attempt to create a drawing. Now this is nothing like drawing in waking life. The image behaves really strangely. Usually I draw just one or two lines, but then the rest of the image gets filled in by the dream. It’s like a live interaction between my conscious and my subconscious mind just playing itself out on the page. When I feel like it’s done, I memorize the image, then I wake myself up and then, back in my physical body, I go back to my desk and recreate the drawing in waking life.5

As if that was not fascinating enough, Dave then let me know that he was collaborating with experimental psychologist Julia Mossbridge and asked if I would like to collaborate on their project. I readily agreed. Julia is convinced that dreams can be precognitive and has carried out experiments the results of which offer support for the reality of precognition. Dave himself is undecided but open to that possibility. Dave and Julia had already carried out a small pilot study—and obtained results that were just about statistically significant. We agreed that it would be a good idea to carry out a second small pilot study primarily with the aim of deciding on the best methodology for a planned larger study.

This is how we carried out that second small pilot study. We decided in advance that we would collect data from five consecutive occasions, each separated by at least a few nights, upon which Dave had a lucid dream. If he did so, he would, while in the lucid state, recall that he was taking part in the precognition study and attempt to create a picture that he hoped would correspond in some way to a target that would not actually be randomly selected until the following day. Upon awakening, he would email me the details, consisting of a brief written description of the dream along with copies of any drawings produced while in the lucid state and reproduced in the waking state.

I would store the dream record digitally on my password-locked computer and only then randomly select a target from a large target pool. This target pool was the “Target of the Week” database, a free online resource produced by Lyn Buchanan for use in parapsychological investigations.6 It includes hundreds of potential targets, each consisting of interesting stories and news events collected from publicly available sources. Each entry might consist of text describing the target, along with photographs and short video clips. I would then send the link to the target to Dave, who would only then be able to access it. Finally, both the dream record and the target link would then be sent to Julia to record in a spreadsheet on a password-locked computer.

The next phase involved judging the degree of match between each dream record and all of the randomly chosen targets. This phase only began once all data had been logged from the first phase. There are different methods available for rating the degree of match, and it is not necessary to go into such details here. The important point is that such ratings can be analyzed statistically—and the degree of match between each dream record and the corresponding target, based on ratings from independent judges, was found once again to be just about statistically significant. In other words, the results of two small pilot studies do offer support for the idea that lucid dreams may sometimes be precognitive.

We are about to begin a larger investigation using essentially the same methodology but this time collecting data across ten lucid dreaming sessions. Having obtained marginally significant results in two small pilot studies, I am obviously intrigued as to what we will find. Will the results of our next investigation also be statistically significant? If so, how will I react? Although I would be surprised by such a result, would it be enough to shake my overall skepticism regarding the paranormal, given my rather long history of failed attempts to find evidence to support the psi hypothesis? I honestly cannot say. At the very least, I would want to carry out further investigations of the phenomenon. If it proved to be reasonably replicable, I would eventually have to conclude that psi is indeed real and that my current skepticism is misguided.

If, on the other hand, we do not obtain statistically significant results, that would probably be enough for me to conclude that the two marginally significant results in the small pilot studies were probably just statistical blips, perfectly explicable as due to nothing more than chance.

Regardless of the outcome of this or any other parapsychological investigation, it is obvious that most people do not base their level of belief in the paranormal on an assessment of the studies published in parapsychology journals. A much more important factor is that of personal experience. This raises an interesting question for me. I have certainly had experiences that a believer would be inclined to interpret as paranormal in nature but that I, an informed skeptic, have explained in nonparanormal terms. But suppose I had one or more such experiences that I felt could simply not be explained away in nonparanormal terms. Might that be enough to convince even me that psi is actually real?

What If Psi Only Occurs Spontaneously?

Some proponents of the psi hypothesis have suggested that it may only operate in spontaneous and unpredictable ways that can never be reliably captured under controlled laboratory conditions. I found myself reflecting at length on this possibility when I received an email out of the blue with the intriguing title “Not a ghost story.” After I had learned more about this intriguing non-ghost-story, via both email and a Zoom call, I asked the sender if I could include an anonymized version of her story in my book, and she kindly agreed. I will tell much of her story by reproducing, with her permission, some extracts from our email exchanges.

That first email began as follows: “I’m sure most of your correspondents protest their sanity at some point, so I’ll get that out of the way right up front! I’m a happy woman with loving family and friends. I have two dogs; I own a house; I’m Googleable in a good way.” As I had a surname as part of her email address, I naturally immediately Googled the name and figured out the identity of my mystery correspondent, subsequently confirmed by the lady in question. She was indeed a reputable person with a solid reputation in her chosen field. I will refer to her as Belle, although that is not her real name.

In that first email, Belle assured me that she had always been a “healthy skeptic” with respect to “all things connected with the afterlife,” but that had changed following the death of her partner, Simon. Simon had died some months earlier while out cycling with Belle. In her words, “Within hours, what are commonly called ‘signs’ began. These were not generic white feathers and random robins, but signs that were so specific to Simon that I could not ignore them.” Belle believed that these signs transcended any explanation in terms of mere coincidence. Intrigued, I asked for more details. Here is a slightly edited version of the email she then sent to me:

This is going to be long—even though I’ll make an effort to be succinct—just because context is important. I’m not going to mention the half-dozen or so incidents of a particular song on the radio or similar things that I feel it’s easy to dismiss as coincidence, even if those things happened at what felt like important moments and the coincidence was notable.

My boyfriend Simon was adopted as a baby and was never interested in finding his biological parents. His mum and dad had lost their first son, Kevin, at 2 years old. I learned this early in our relationship, but it was not something he or his family really talked about. After they adopted Simon, his mum and dad went on to have another boy and a girl, and Simon simply considered himself the big brother.

Simon and I were together for nearly 14 years. I had always been very cheerfully single and found him a bit over-enthusiastic at first, but he was so funny, kind and clever that he won me over. He had a teenage son, Ben, and they lived 20 minutes away, which was perfect.

In 2012 Simon got mouth cancer and underwent multiple radical surgeries, chemo, and extensive radiotherapy that left him unable to speak and eat properly. He went through years of treatment, setbacks, and aftermath with the most incredible bravery and good humour. As part of his recovery he rediscovered cycling and got me into it too, and we would ride miles and miles every weekend.

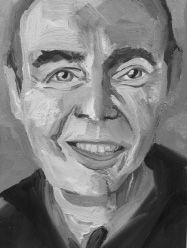

When we saw each other we’d watch TV or go to the movies or stand-up comedy shows. Our favourite TV show was Sky’s Portrait Artist of the Year, which I wasn’t allowed to watch without him. Encouraged into overreaching myself, I once even painted his profile while we watched the show [figure E.1]. It was so bad I didn’t finish it and we both agreed I should hang on to the day job.

I love horse racing. Simon always teased me because even though I bet on horse racing every day, I only spend 50p here and £1 there.

We played poker every Sunday night with friends. Simon’s poker name was Sweetie because I called him that once and it stuck. The other men would call him that sometimes. Always got a giggle.

Figure E.1

Belle’s unfinished portrait of Simon. Image courtesy of Belle.

I bought a trombone with my poker winnings once, but I was so embarrassingly bad that I rarely played it. Simon encouraged me all the time. He bought me a stand and a course of online lessons for one birthday, and later a DVD (which I did not open) called Play Trombone Today! He was always asking if I’d practised. I never had.

We never argued. Just never. Never took each other for granted. Every year our relationship grew stronger, kinder, and funnier. There were only two things we disagreed on—heavy metal and the paranormal. Simon was all about the heavy metal and science. His bad taste was something I could do nothing about, but I—even though I was pretty skeptical myself—used to wind him up by insisting that not being open to things like ghosts, reincarnation, and telepathy is actually unscientific. It was an argument he couldn’t refute. Luckily we were both rabid atheists, so we could always find our way back to common ground.

At the start of the first [COVID-19] lockdown I was diagnosed with cancer myself. I had surgery, radiotherapy, and chemo, but in January last year my cancer had spread anyway, and it looked like curtains. I made my will, bought a plot in a natural burial ground, and insisted on taking my family there as part of being able to talk freely about my death. When Simon visited the burial ground, he asked if he could be buried next to me.

At the eleventh hour I was put onto immunotherapy, which saved my life. Slowly I started to feel better, and around August last year I even got back on my bike—although it was very slow going at first.

Simon would come over on Saturday night, and we would go for a bike ride on Sunday morning.

The night before he died, we watched a movie called Jeff Who Lives at Home. It’s a small indie film about a slacker who is obsessed with “signs.” Throughout the film Jeff follows the sign of “Kevin.” Following Kevin takes him through an adventurous day and ends with him saving a man’s life. Spoiler alert: the guy’s name is Kevin 🙄 We both loved the film and chatted about it that night and the next morning as we got ready to go out.

Simon felt cold and a bit weak the whole ride, and it was cold and overcast, but it wasn’t like him to voice any concerns about himself, so after about seven miles I suggested that we cut the ride short and turn around. As we set off for home, with him setting a nice slow pace, the sun suddenly burst through the clouds, and he said “Oh, sunshine!”

About 30 seconds later I heard a car behind us. Simon was riding about 2 metres from the kerb so I said “car.” But he didn’t move back in, so I repeated, “Simon. Car.” But he veered into the middle of the lane and died, literally on his bike, then fell into the road.

I’ll call it a heart attack, although it was something harder to spell.

OK, so this is where things started to be a bit weird . . .

The police drove me home and I gave them his sister’s number so she could tell his parents, who live a couple of hours away.

A few hours later his sister called me and I asked how his parents were doing. She said her dad was okay but that her mother was in a terrible state. Then, without any prompting she said: “Remember, Simon was adopted to replace Kevin.”

I felt it was an odd thing for her to say at that moment, and the coincidence of the movie we’d watched the night before felt big, but not paranormally so.

I then had to go to tell Simon’s son what had happened. Trying to reassure him that Simon had not suffered and that all that could have been done for him had been (three doctors—one an oncologist—were giving him CPR within 30 seconds), I told Ben his last words and it was only when he burst into tears that I remembered that “Sunshine” was what Simon always called him.

Again—a little moment, and a comfort, but not something I’d be writing to you about on its own.

A few days later Ben and I went to see Simon’s parents. They’re old-school stoical people, and although they were upset, they were still all about making tea and offering biscuits. Out of nowhere his dad asked if it was December 5th that Simon had died, and when I confirmed that it was, he said, “That’s the date we lost Kevin.”

That weekend I took my mother shopping. While I waited for her in the car park, a man walked towards my car. I noticed him because he was holding something very awkwardly under his arm. As he passed me, I saw it was a bag-for-life, folded so that only one side of it was showing, and held awkwardly, so that his arm was not across it. It was red, and had the words “HELLO SWEETIE” on it.

After he passed my car, he shifted his position to a more natural one, and covered the bag with his arm.

It was at this point that I started to think these things may be signs from Simon.

Figure E.2

Similar profile in the road to Belle’s unfinished portrait. Image courtesy of Belle.

A few nights later I had a dream that my sister Chloe and I were at a sort of street parade through a town centre where she lives. She’s got a lot of hippie-type friends and she was introducing me to all sorts of jugglers and ballerinas and there were horses everywhere. In the middle of it all, I spotted Simon through the window of a coffee shop. I rushed off the street and hugged him but he was very sad and knew he was about to die. Then the dream switched to him dying in my arms. Regardless, I was happy I had hugged him again because it felt so real, and texted my sister about the dream.

She called and told me that the same time I was having this dream, she and her family were at the Mondol parade in Penzance, where she had just moved, and that there were dancers and jugglers, also many people wearing horse skulls. I’d never heard of the parade but it’s a thing!

I was so sad after Simon died that for a couple of weeks I just sat and did nothing. Finally, I decided to go for a walk. There’s a three-mile loop outside my house so I set off. I was pretty emotional all the way around and then about a mile from home I saw Simon’s profile in the road [figure E.2]. I have walked this loop before and since and never seen anything like this in this spot, whatever the weather conditions, but I immediately thought of the painting I had done of Simon. I didn’t bother finishing it around the glasses and this profile also looks unfinished in the same place.

Figure E.3

Photo of Simon with a sparkle in his eye. Image courtesy of Belle.

My mantel clock had stopped on the day that Simon died, and I hadn’t had the energy to wind it up, so a few days later I went to do that but the hands wouldn’t move. This is a clock I’ve had for years and it’s always kept lovely time, but now it is stuck at 10.23. Simon’s time of death (called on the road by the doctor who attended with the ambulance) is listed on his death certificate as 11.04. I estimated at the time that the doctors and I gave Simon CPR and mouth to mouth for about 10–15 minutes before the ambulance arrived. They worked on him for about 30 minutes before he was finally pronounced dead. 10.23 would have been almost exactly the time when he died.

I became seized by the need to paint Simon’s portrait. I became so restless I couldn’t do anything until I had, so I went and bought proper paints and canvases and an easel. I chose to copy a particular photo of Simon because of the sparkle in his eye [figure E.3]. Apart from that dreadful profile, I hadn’t painted for maybe 15 years, and was never very good! Again, as I painted I became overwhelmed with emotion, particularly with self-doubt. I started to sob as I painted, but was suddenly aware of the feeling of something guiding me. Every time I hesitated to make a stroke, I could feel something telling me that it was right, and I would make the stroke and it was right. It was the most bizarre experience. I was painting and sobbing, sobbing and painting, and I just kept thinking, “As long as I get the sparkle in his eye, it will be OK.”

Figure E.4

Belle’s finished portrait of Simon. Image courtesy of Belle.

And it was! Here are the photo and painting [figure E.4], which I’m sure you’ll agree is an awful lot better than the painter of that profile had any right to expect—and does capture the sparkle in his eye.

When I finished the painting, I realised I’d missed all that day’s racing! Only the evening meeting at Wolverhampton was still available, so I opened up my betting app and looked at the first race.

There was a horse running called Sparkle in His Eye.

Came in at 8–1.

With my £1 weighing it down, of course!

A few days later I dreamed that Simon showed me Elvis as a young man in uniform, but with angel wings behind him. In the dream I said to Simon, “Oh, you won your wings!” I was happy for him but sad for me, because I felt that it meant Simon would be moving on now and not send me any more signs.

When I looked at the racing that day there was a horse called Win My Wings, which won at 20–1.

In March I found a childhood toy had fallen off my bookshelf.

He’s a soft penguin I got as a toddler, and has sat on the bookshelf in the same place for years.

I picked him up and put him back on the shelf.

The next morning, he had fallen off again.

I put him back.

Third morning, same thing.

On the fourth day, Pengie had flung himself across the room. Please consider:

- 1. I live alone

- 2. The penguin is a flightless bird. 😉

So this really made me stop and wonder if it was a sign. I couldn’t work out why Simon would be chucking my penguin across the room. As I went to put him back in place, I looked at whatever he had been hiding: it was a DVD . . . Play Trombone Today!

I did and I do, and Pengie has stayed put ever since.

So . . . Simon is buried in my grave, and I’ve bought the plot next to his. I haven’t had a sign from him for a little while, but tbh I don’t feel the need for any more—I’m so grateful for the ones I’ve had and they have changed my life. Signs from the arch-atheist have led me to belief—first in the afterlife and finally in God. To not believe in the spirit world after what I’ve experienced would be ridiculous; to not believe in God finally just felt churlish. Since I gave in on that point, I’ve had a couple of funny religious “signs” but this is about Simon, so I’ll leave it at that.

I think it’s almost impossible to convince others of the paranormal, but once it happens to you, there’s simply no denying it.

Most of the individual “signs” that Belle described can no doubt be explained away as just coincidences, and the resemblance of her first attempt to paint a portrait of Simon to the profile she spotted (and photographed) on the road may be nothing more than a nice example of pareidolia. The flying penguin toy may be harder to explain, but even that may have been open to a nonparanormal, if obscure, explanation had it been properly investigated at the time. But what is undeniably striking about Belle’s story is the occurrence of so many odd events in such a relatively short period of time following Simon’s death.

What I want you, as a reader, to do is to imagine yourself experiencing a similar run of odd events following the death of a loved one. I am sure many readers of this book would describe themselves as skeptics, but would your skepticism be shaken if you had similar experiences to those described by Belle? Merely reading about Belle’s experiences was certainly not enough to shake my own skepticism, but that is because they happened to her. Would I still be so skeptical if they had happened to me? I honestly cannot say.

Although I have no doubt that Belle really was a skeptic before these events occurred, there may be readers who doubt that. After all, we are all familiar with those paranormal anecdotes that begin, “Before this happened to me, I was the most skeptical person you could imagine . . .” and then go on to describe the amazing events that forced them to acknowledge that the paranormal is real.7 I have yet to come across anyone who began such an anecdote with the words, “Me, I’m the most gullible person you could imagine!” Would a series of amazing coincidences ever be enough to convince a “proper skeptic” to seriously entertain the idea that the paranormal is real? The answer is yes.

From Skeptic to Zetetic

As stated at the beginning of this epilogue, I used to illustrate the opposite extremes of the paranormal belief continuum to my students with quotations from Dean Radin and David Marks. There is absolutely no denying that for much of his career, Marks was a complete skeptic regarding the paranormal. He not only wrote one of the most influential critiques of the paranormal ever, he was also one of the co-founders of New Zealand Skeptics.8 However, in his recent book, Psychology and the Paranormal, he has softened his position considerably, preferring to describe himself as a zetetic in contrast to what he describes as his previous “entrenched skeptical stance.”9 He defines a zetetic as “a person who suspends judgment and explores scientific questions by using discussion or dialogue to enquire into a topic.”10

In Psychology and the Paranormal, he reviews evidence from several areas of experimental parapsychology, including telepathy, precognition, and psychokinesis. His conclusion is as damning as it ever was: “In spite of the continuing claims of advocates, the facts show that reliable, replicable laboratory evidence of psi has not been demonstrated.” Marks concisely summarizes his new position: “If psi exists, it happens in a spontaneous, unpredictable and uncontrollable manner—e.g., as a remarkable coincidence or other anomalous experience.”11

Marks describes in detail one such coincidence that he experienced and the profound impact it had on him. He refers to it as “The Chiswick Coincidence.”12 One day in August 2018, Marks found himself with time to kill. He could not go home, as an estate agent from the company Chestertons had arranged a viewing of his apartment for a potential tenant. He decided to go for lunch in a pub next to the Thames called the City Barge. He then opened his Kindle and decided to continue reading a novel he had started a few days earlier. The novel was The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare by G. K. Chesterton. The ancestral family of this author founded the estate agents of the same name. As he began to read, Marks realized that a pub described at that point in the novel was the very pub that he had moments ago decided to visit.

Marks describes in total what he refers to as “seven layers of synchronicity” associated with this coincidence. They include the fact that Martin Gardner, who had written the foreword to Marks’s own classic, The Psychology of the Psychic, had also written the annotations for a special edition of Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday. Marks had been unaware of this prior to carrying out further research into his Chiswick Coincidence.

Marks estimates that the overall combined probability of his seven synchronicities is somewhere in the region of one in a quintillion (that is, a million million million). He concludes, “These odds are so astronomical that one must consider the possibility of a paranormal explanation. Not to do so would be irrational and contrary to open inquiry.”13 This from an erstwhile vocal skeptic who has written extensively about the psychology of coincidence in his previous publications.

Concluding Comment

For me personally, robust, replicable evidence in support of the paranormal from well-controlled scientific studies would always be much more convincing than any number of anecdotal accounts reported by others, no matter how compelling those accounts were to the people reporting them. Therefore, if psi really does exist but it is in the very nature of psi to elude such controlled experimental demonstrations, it may be that the truth about psi will always be beyond my reach. Or perhaps, like Belle and David Marks, I will one day experience one or more events that I deem to be so remarkable that I decide that psi is real even if it cannot be proved to exist scientifically.

The late Robert Morris pointed out that one of the founding fathers of modern psychology (as well as of the American Society for Psychical Research) had considered this issue of where one draws the line with respect to deciding one’s beliefs. I will finish with his wise words:

William James (1907/1968) makes the distinction between two kinds of people, the tender-minded and the tough-minded (I prefer to call these people hard-headed). Tough-minded people are those whose love for the truth is so great that they want to be sure that truth is all they have, and so they exclude all information, all procedures which do not meet very strict criteria by which they can know they have the truth. On the other hand, the tender-minded are individuals whose love for the truth is so great that they are willing to risk error in taking a chance to grasp the truth. One approach is conservative, the other is liberal. One approach is restrictive, the other approach is expansive. As James points out, whether or not a person is one type or the other is very much a product of his temperament.14