It’s several months later, a year and a half after my mother died, and my father and I are going to visit her grave again. But first, a tour of the past, a drive down memory lane. In his cluttered car that smells a little rank, we cruise the old suburb. Today I’m not finding it as unattractive as I used to. Or is it that I need a new prescription for my glasses? We visit the library where my mother worked for thirty years. It used to look so ungainly and modern. Now it looks comfortable with itself, stately and purposeful, with ivy growing on brick walls. Inside, under a high, renovated ceiling flooded with light, we look at the desk where she sat with the reference books and microfiche machines she knew so well. She was a core of this library, a reliable face for everyone who used the place. And a pretty good shusher, too. Shhh! Dad is trying to tell the staff all about her now. They’re young and look at him with blank stares. Nobody remembers who she was or even recognizes her name. I tell him they’re very busy and to leave them alone. But can’t they even pretend to be interested? Has it really been that long since she retired?

Around the corner, our house has been fixed up by new owners. There’s elegant landscaping now, ornamental trees and shrubs where there used to be scraggly pines. A tasteful porch has been added to the front. Somebody has seen our house as we never saw it and has put an effort into bringing it up to a level my parents could never imagine. The whole neighborhood looks nicer than I remember, with wide streets bordered by canals and the bright expanse of Great South Bay all around that I took for granted for so many years.

“Why did I dislike it so much?” I ask. “Why was I so unhappy here?”

Dad doesn’t know. And I can’t say I’ll ever know either. I’ve always been insecure, and I’ve always liked to complain. And without anything important to complain about, I guess I needed something, anything, to pick on for all those years. But now I think I’m finally tired of my unhappiness. Maybe all it takes is an adjustment, a decision, like when you stop looking for perfection in a mate and finally fall in love. Maybe happiness isn’t as alien to me as I had thought. Isn’t it in my DNA? Look at my father.

At the end of our old street, he makes a left turn onto the Montauk Highway. We pass rows of medical buildings. We pass the road to the high school. I feel like I’m a teenager again, cruising with a buddy with nothing but time on our hands.

“I didn’t get much of an education here, but I guess I did okay,” I say.

“You did great,” he says.

“I don’t know about that.”

“It’s just a matter of how you look at things, Bobby,” he replies, as he hugs the center line and makes me grip my seat. “Besides, where you’re from doesn’t mean a thing. Look how well you’ve done. You can go as far as you want with your life.”

He’s said this to me since I can remember. But for the first time, I hear it.

What do fathers do for sons? Most of them know they have to be providers. Many of them bond over tennis or golf or fishing trips. Some leave their sons a business. Others leave governments in their hands or create political legacies that can put them in the White House. Some, like Daedalus, are too ambitious, and make their sons fly, like Icarus, too close to the sun. Others are impossible to please. Not my father, my biggest fan, who revels in my life. Finally, as I look into the near future of my own old age, I can see that it isn’t the quality of all those observations or suggestions he is so anxious to share that matters. What matters is the sincerity of the intention, his pleasure in participating in life with me. Even without a father of his own, he has figured out how to express his affection fully, one of the hardest things to do for men of his generation. He has encouraged me to speak up and sing out, unashamed. He has made me see the importance of demanding romance from life, regardless of how elusive. He has showed me that it’s okay to be vulnerable and a little foolish. He has taught me half of the songs in my repertoire and several pretty good dirty jokes, too. Not bad.

We drive west on the industrial Route 109, into the late-afternoon sun, and then pull into Mount Ararat Cemetery, passing rows of identical gravestones before he parks his car. This time we don’t get lost when we walk to Mom’s grave. Maybe it’s the weather or time of year. Maybe it’s all the Sudafed I had to take this morning. Or maybe it’s being in love and knowing my father is, too. For whatever the reason, this time I can’t dismiss this place with such a critical eye. It doesn’t seem unattractive to me now. The trees are blooming in shades of yellow, pink, and white, and it’s very pretty.

“You know, Dad,” I say as we stop at my mother’s grave, now with grass fully grown in around it, “I was just thinking, maybe I will be buried here with you after all.”

Dad looks surprised. “But I thought you don’t like all the traffic noise,” he says.

“I don’t,” I say. “But since I’ll be dead, maybe it won’t bother me so much.”

He laughs. “Good point.”

“Yeah, I’ll be buried here if your offer still stands, but you know that there’s going to have to be room for more than just me.”

He breaks into a smile.

“I was hoping you’d say that, because I just signed for a plot for Ira here, too,” he says. “So now we can all be together at the end for a nice long visit.”

“Perfect. Thank you, Dad.”

We’re quiet for a moment, basking in something that I’d have to say is contentment. One old man, one middle-aged one, finally settling in together. We stare down at my mother’s grave. The budding maple tree branches over us bow in the breeze.

“Those last years were so hard,” I say.

“I wish I could have done better for her,” he replies. “I just didn’t know how.”

I feel the old resentment for a moment. Then I think of my mother, right here with us. And just like that, I let it go. It wasn’t his way to worry, to be dutiful every moment of their marriage. She was the reliable one, like my brother. He was the fun one, the one who made her life amusing—irritating, never dull.

“You know what, Dad? You did the best you could do.”

“So did you, Bobby, so did you.”

He leans over and puts his arm around me. Then he leans in for one of his bonding bear hugs. This time I don’t squirm. I turn and face him, and I open my arms and take him in. His cheek feels smooth against mine. His hair soft against my forehead. His chest expands and contracts. After we pull apart, he’s quiet. Then, just like he does each time we’re here, he looks down at my mother’s grave to serenade her. “Honey,” he says. “This one’s for you.”

When somebody loves you

It’s no good unless he loves you

All the way.

His voice shakes a little. He doesn’t quite have the breath he used to. But as always, his pitch is perfect, and his delivery is smooth as any crooner’s.

Happy to be near you

When you need someone to cheer you

All the way.

He lets the lyrics linger in the air, then he turns to me.

“You know this song, Bobby,” he says. “Why don’t you sing with me?”

So I sing with him, hesitantly at first, then with more conviction. Our voices wrap in harmony, twisting together, and as indistinguishable as a couple of blackbirds in a tree.

Taller than the tallest tree is,

That’s how it’s got to feel;

Deeper than the deep blue sea is,

That’s how deep it goes,

If it’s real.

Suddenly seized with the thought of how shocked my mother would be to see the two of us getting along so well, I laugh. Then emotion wells up inside—grief, happiness, and everything in between, and my eyes fill with tears. My father puts his arm around me, holds me close.

Who knows where the road will lead us?

Only a fool would say.

But if you let me love you,

It’s for sure I’m going to love you

All the way.

When it’s time to go, we walk along the pebbled cemetery path and get back into his car to head home to the brand-new lives we have ahead of us. We’re going our separate ways. Yet we’ve never been closer. Then I sit down in the passenger seat, and, as he starts the engine, I put my brand-new, four-hundred-dollar, brown suede Prada loafer into a half-eaten tuna salad sandwich, heavy on the mayo.

“Dad! What is this?”

“Don’t throw it out,” he says. “I’ll have it later.”

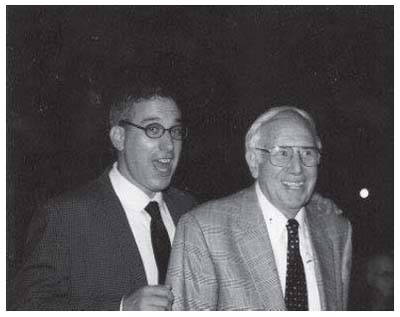

The author with his father in 2003 (Courtesy of Bob Morris)