When the movie PT 109 came out, in June of 1963, Jackie Kennedy invited the entire Kennedy clan to watch it in the White House theater. Several members of the President’s cabinet were also invited, along with their families. We, the McNamaras, were among the chosen ones.

I can remember this event as if it were yesterday. It was a warm summer evening in Washington. We made the drive to the White House, a route that was soon to be familiar to me. Sunlight was still streaming into the theater doors and the room was packed with kids as the film began. Jackie had set out large pillows for us to sit on. Children were running around everywhere. The President’s rocking chair, draped in green fabric, was right up front for the best view.

The movie is based on JFK’s service in the Navy during World War II. Cliff Robertson stars as John F. Kennedy. It was the first movie of its kind: a war thriller about a sitting US president. Once the lights went down and the movie flashed on the screen, I was mesmerized. The excitement of watching a war story set in the Pacific with the President in attendance was overwhelming to me as a thirteen-year-old. I wonder now what it is like to watch one’s own exploits mythologized. I suppose Jack Kennedy had gotten used to it.

I strongly remember watching him watching himself. To me he seemed warm, exciting, and somewhat distant, even though the physical distance was short. I can’t say that I knew him. But sitting on the floor so close to a man who was placed at the center of history, whose inauguration I had attended, how could I not fantasize about moving that impossible distance from his periphery to within his halo? From my pillow to the chair—a small step, great in the heart. My father was very close to the President, and this was something to be proud of.

I was in school at Sidwell Friends when President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas. The news was spoken over the loudspeaker on that Friday afternoon. I don’t remember our principal’s exact words. We were told that school was closing and that our families were coming to school early to pick us up. The hallways were crowded but silent as the shock wave rolled us out the doors. Our first sock hop had been scheduled for that evening. I was president of the student council, and I had organized the dance. I had been looking forward to it, and it vanished in a flash. Saying this now, reflecting on myself as a middle schooler, I’m surprised to remember that I was a leader at that age. In my recent years in public service, I have found my footing in that role. I want to be in the know, I want to be remembered, and I want to be a change maker. Surely some of that desire comes from my close proximity to the President who was killed.

After the assassination, I spent a fair amount of time with Jackie Kennedy and her children. She moved into a home on N Street in Georgetown. I would visit Caroline and John after the end of my school day. They were much younger than me, and this was like a baby-sitting or big brother relationship. On occasion, I would bring John a model plane from my own collection. Together we would race up and down the staircase, pretending that we were flying, jumping from the last steps and flapping our arms in the air. I loved those times with the children. They helped me understand that life would go on. It distracted me from the pain of months and years following the assassination.

After the playdates, Jackie sent me several notes, writing on behalf of John, expressing his glee from our times together. In one of these, “he” says:

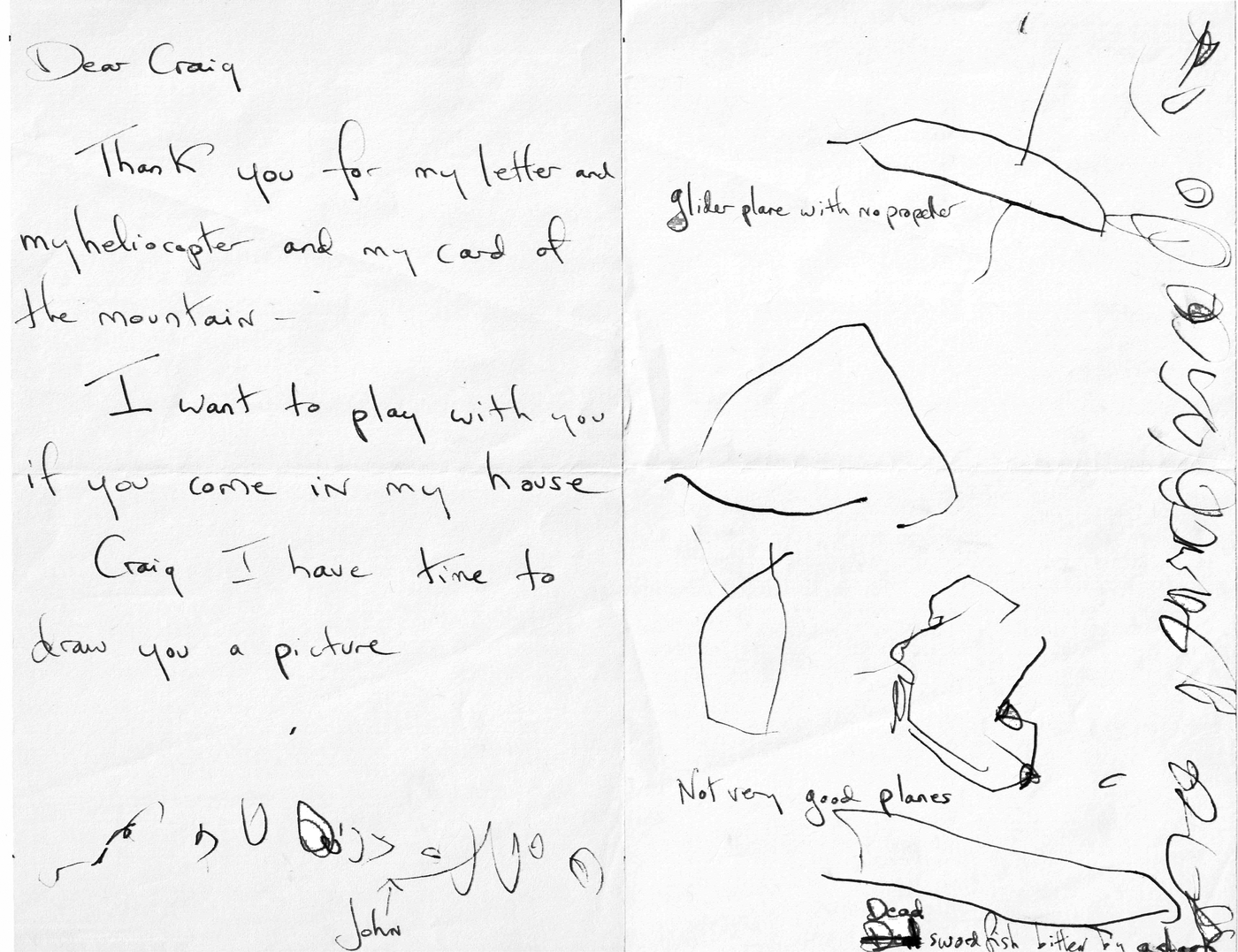

Dear Craig,

Thank you for my letter and my helicopter and my card of the mountain—I want to play with you if you come in my house. Craig, I have time to draw you a picture.

John then draws a “glider plane with no propeller,” some “not very good planes,” and a “dead swordfish bitten by a shark.” I was old enough to appreciate that these were special notes, and I kept them.

It’s unbelievable to me that I never again met John John. Although we were ten years apart in age, it would seem that our lives might have intersected. My father’s relationship with Jackie grew stronger each year. But that’s precisely the point: Dad rarely extended his personal life to me.

Reading John’s cards today, I find them bittersweet—knowing of his early interest in planes, knowing how he died. More than that, they’re haunting. That loss is like a strange and dissonant chord playing over memories of those times. It doesn’t go away; it resounds. It reminds me of the feeling I have when remembering my short-lived relationship with Rich Rusk. We shared a singular experience of growing up in the foreign policy power structure, and of coming out of that experience with significant torments. But he’s gone. Who else can share that with me?

Even the loss of a friend is incalculable and long-lasting. The unknown suffering, the silent wondering. When comparing that with the assassination of a President and the nightmare of a war, I am overwhelmed by the thought that nothing really goes away.

Some months ago, I was researching Jackie Kennedy’s life after 1963. I found an article in Vanity Fair. The piece mentions my parents.

When Secretary of Defense Bob McNamara and his wife, Marg, sent over two painted portraits of J.F.K. and urged her to accept one as a gift, Jackie realized that though she especially admired the smaller of the pair, which showed her late husband in a seated position, she simply could not bear to keep it. In anticipation of returning both paintings, she propped them up just outside her bedroom door. One evening in December, young John emerged from Jackie’s room. Spotting a portrait of his father, he removed a lollipop from his mouth and kissed the image, saying, “Good night, Daddy.” Jackie related the episode to Marg McNamara by way of explanation as to why it would be impossible to have such a picture near. She said it brought to the surface too many things.

Rereading this article, sitting at my desk in my farm office, I find myself looking around at the many “portraits”—images, more accurately—of my father with which I have surrounded myself. On one wall I have a picture of him walking with LBJ. Close by, there is a picture of him in his old age, around the time of his interviews with Errol Morris. There’s a picture of the two of us together on one of his birthdays, wearing coats and ties. There are disembodied portraits of him, like his silver calendar. On occasion I’ve polished the silver calendar, a process that has removed the oils left by my father’s skin. Yet the calendar, to me, is the hand of my father. Whenever I lift it, I’m gripping my father’s hand. It’s a loving gesture.

Keeping an image nearby is painful. It’s easier, in many ways, to throw that image away. Or, as Jackie contemplated, to refuse that image. Disowning my father, getting rid of his image, would enable the conviction that he is not part of me, that I am not like him, that his actions do not continue to weigh upon me, that they have faded from the lifeblood of the world and have run out on the reel of history. None of that would be true. To say that I hate him, to call him evil, to deny the love I have for him—these things would seem, temporarily, to relieve certain pressures. But they wouldn’t be the truth. I don’t want that, because I want to be honest. It’s impossible not to be my father’s son; I can’t be but what I am. This is not the end for me.

Jackie Kennedy’s handwritten note to me on behalf of her son