ROYCE’S MOTHER’S HOUSE on Brougham Street was number 74. It was square and old and set back a long way from the street, with a massive bloody lawn in front that he had to do with a push mower. Sometimes, but not very often, old Scotty Ames would come over from next door with his Flymo and do it. Then Royce would have to walk in front and check for stones. One stone and old Scotty was off – he was very proud of his Flymo. And his lawn.

He was proud of Royce’s lawn, too, if truth be told, because of how quickly it dried out after rain – just like his. Usually, ten minutes after the rain stopped, Scotty’d be out there, droning over his lawn with his Flymo. ‘Good publicity for the district, this,’ he’d shout over the roar. ‘Can’t mow your lawns ten minutes after a storm in Christchurch, you know.’

He’d told Royce the technical side of mowing after rain. ‘Limestone, see? Water goes through it like through whitebait netting.’

Seems there was a limestone outcrop that lay under just his place and Royce’s. An isolated outcrop it must have been, because water lay on the Roberts’ lawn next door for ages. And same for Perce Kidder’s lawn on the other side of Royce. They weren’t on the limestone outcrop, poor buggers, explained Scotty.

It was this limestone that made Scotty reckon the Maori land claims that had started up again recently had nothing to do with his place. ‘The ground at my place is made of limestone that was there long before the Treaty of Waitangi! They’ve got no claim on my land.’

One day Royce had been a bit bold and said, ‘I don’t reckon it’s anything to do with limestone, Mr Ames, I reckon it’s just that the Flymo floats over the wet ground.’

‘You watch your lip, boy! It’s because of pre-Treaty limestone! And don’t you go telling the Maoris about my bloody Flymo, neither.’

NUMBER 74 BROUGHAM Street had belonged to Royce’s father’s father. He hadn’t built it – although he could have, because he’d been a carpenter. When Royce was little, his grandfather had moved out into a pensioner’s flat and sold the house to Royce’s parents. Then he died.

The funny thing is, they kept paying for it. Why? What was the use of paying money to a dead person? Where did it go? These were big questions that weren’t answered until Royce got to Tech and found out about banks and mortgages.

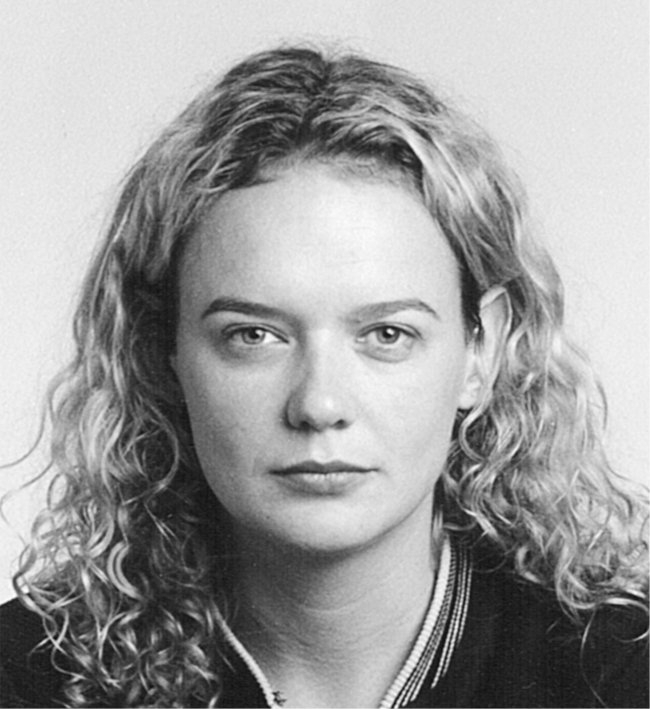

Recently he’d become seriously interested in banks. In particular the Bank of New South Wales. Its manager was Karen Phibbs’ father: little bloke with bulgy blue eyes and a laugh like a tap dripping. Mrs Phibbs was taller altogether, and quite good-looking – which is where Karen got her quite good looks from. But she had the ess lisp too, so she’d had to make do with a little dork like Mr Phibbs.

Mr Phibbs played golf and so did Mrs Phibbs. On Sunday afternoons they’d go out to the golf links, and Grant Franklin from 6B would sneak into the front room of the bank house and he and Karen Phibbs would ‘pash’ – according to Grant.

Yeah, you can imagine what that’d be like: ‘Oh Grant, darling, not there, not my elbow; you know I can’t control myself when you touch my elbow.’ Be like a hot night down at the Darby and Joan Club would that particular pash session.

Grant lived out country. He used to come in for his Sunday pash in a car. His own car. It was a white Anglia that his father had bought him because Grant was ‘so responsible’. It was the only pupil’s car in the district, but then fuddy-duddy Grant Franklin was probably the only pupil whose parents thought he was ‘so responsible’.

He didn’t like to park it outside the bank in case people started to notice it, but neither did he want it out of his sight in case some jealous bastard let his tyres down or something. Now, 74 Brougham Street was only two blocks away from the bank, and old Grant wasn’t such a bad guy really – played on the other wing for the First Fifteen, though he couldn’t tackle for nuts – and the upshot was, Royce’d said to him why didn’t he leave his car at his place, where it’d be safe? So he did. You’d generally hear it swishing up the wet concrete side-road behind Perce Kidder’s at about 1.30 on a Sunday.

Sometimes Royce used to race to the front door and bellow: ‘Got your rubbers, have you, Grant?’ as the poor mortified bastard headed up the street to the bank.

The only interesting thing about all this was that the back of the bank safe stuck out into the front room that Grant and Karen did their pashing in. You couldn’t get into the bank itself from the house, because of steel doors and whatnot, but there, facing the sofa, said Grant, was the back of the safe. About six feet by six feet, sticking into the room. ‘Made in Kalamazoo’, said a label on it.

‘You’d think they’d wallpaper it or something,’ said Grant, ‘or at least paint it. It’s just a big ugly grey square in the wall.’

‘Does it move?’ asked Royce.

‘Come on, it’s probably bolted into concrete inside the bank.’

‘How thick’s the metal?’

‘Well, you can see a join if you look sideways, along the wall. I’d say about two-thirds of an inch. Plate steel.’

Royce used to daydream about that safe. Thousands and thousands of dollars – millions, maybe! – just two-thirds of an inch away. One night he had a real dream about it. He was with Karen Phibbs on the sofa of the bank house – God knows where Grant was; he’d been locked out of the dream – and she’d said, ‘Do you know what stops you just walking into that safe?’

‘No,’ he’d replied, in his dream.

‘Clothes. All you have to do is take your clothes off and you can walk straight through that steel wall. Watch.’

Well, it became an erotic dream after that and all but turned into a wet dream. He’d looked at Karen Phibbs in a different light for the next few weeks, and made some quite revolutionary plans. Until the esses drove him mad again and he went back to just day-dreaming about the safe.

In metalwork he practised drilling through plate steel. He’d stuffed God knows how many drills and got into all sorts of trouble with Inky before bloody Grant Franklin told him it was probably made of hardened steel that school drills wouldn’t get through anyway.

His boldest scheme was to talk to Terry Ohern about explosives. Well, to start to talk about explosives. Terry was in the fourth form – he was fifteen but they’d kept him back a year. (Sheesh! You had to be dumb to be dumb around here.) Well, talking of dumb, Terry was great mates with Feefi Fyfe. Feefi was a bit of a giant who lived with his mum out the Fairdown Straight. He was only fifteen too, but was about as big as you can get without turning into something else. Apparently he’d been born with a bit too much Darwinism in him. He was a great kid and everyone loved him, but he was a bit dangerous at times so they didn’t let him come to Tech. In fact they’d sent him up to the mines to sort of work off his energy. Can you imagine that? At fifteen, down the mines, shovelling for Jimmy Prince?

‘Do you reckon Feefi could get us some gelignite, Terry?’ Royce’d asked one night, down at the Albion. ‘Bank job, you know?’

Having a kid two years younger than you look up at you with contempt in his eye puts quite a dampener on things. ‘Jesus, Royce, are you nuts? Your hat’s on too tight, man.’

That had more or less been the end of the bank job. It had certainly been the end of the conversation, because not long after that Terry’s dad Brian came into the pub and whispered: ‘What the fuck are you doing here? You’re not old enough!’ ‘Well, you should have had me sooner,’ said Terry, which was a pretty good answer, but the mood was spoilt. He slunk out not long after, not able to look his father in the eye across the bar.

Anyway, Royce’d put robbing the BNSW on the back-burner – although never quite forgetting about it entirely. Meanwhile Grant Franklin continued to turn up most Sundays to go down to the bank for his pash with Karen Phibbs, leaving his car on the cracked concrete back yard under the clothesline at number 74 …

HOLY KERMOLEY! CLOTHESLINE! He had no shirt, no socks, no smalls! They were all on that line, soaking wet, and he had a 4.30 date. Linda Harvey at the Doo Duk Inn.

She wouldn’t go near the Gren, of course, though he’d told her time and again that half of 5bloodyB went down there of a Sunday afternoon – hell, you could hear the strains of Debbie Boone and ‘You Light Up My Life’ from half a block away. But no, not a pub; not yet.

‘Not yet’ was a phrase that had taken on immense importance recently. Just out of the blue the other night, down at the Square when they were doing laps – too cold for training – Linda had said, ‘I’ve a feeling things are going to be different when I’m seventeen.’

November 30th, he knew that. ‘Yeah? How?’ A hard had come on, without him even thinking of his memory of her.

‘Oh, just the way I see things.’

‘Don’t feel like changing now, do you?’

‘No,’ and she’d given him a little punch, ‘not yet!’

So, for all he knew, he’d just had his first dirty conversation with Linda Harvey. But then again, he might not have, too. Might just as easily have meant she was gonna do the high-jump instead of the long.

Annoying thing was, you couldn’t risk it. If she wanted to go to the five o’clock pictures you had to go, in case this was the day ‘not yet’ became ‘now’. So he’d have an impatient lemonade at the Doo Duk, while she sipped her ‘white coffee’, then they’d go off and watch Bambi or some other socially ruinous friggin’ thing, and wouldn’t even sit in the back row.

She was so dumbly nice she didn’t have a clue that it was his popularity – in a way – that kept her in the social picture. Her reputation was being added to by being with him, while his was being subtracted from, by being with her. By cripes he’d be pissed off if it wasn’t him she turned to when the facts of life kicked in.

They were actually going to Annie Hall, which was evidently pretty boring except the shorts had a Pathe report on Leon Spinks beating Mohammed Ali. She’d rung him and asked if he’d like to go, and he’d said (oh God) of course, so here he was, having to fork out $3 each for a film that Gilbert said had only two people in it. Hell, compare that with Star Wars!

The major issue right now, however, was getting dressed. He didn’t have a thing to wear. It was wash day. His mother had put his shirts, socks and smalls into the washing machine before she went out to change her Mills and Boons at the library, then plugged them all onto the line. Clean and wet.

Royce went out to the clothesline: ‘She hangs a good line of washing,’ he’d once heard old Mrs Ames say about his mother. The line visible between the clothes was shiny with constant use. He looked up into the sky. It was only a few metres above his head. He wet his finger and held it up. No wind. The day was grey, still and misty – you could see the damp ingredients of colourless rainbows hovering above the limestone lawn. It was not, as his mother would say, ‘good drying weather’.

ROYCE HUNCHES OVER the wheel, holding it into his chest like a ball at the bottom of a ruck. Speed is exhilarating but not relaxing. Not yet anyway. Not to someone who’s driven only twice before.

The flax strobes past both side windows like bent picket fences; the white lines down the middle of the road are tracer bullets aimed just past his right wing mirror. Christ: eighty miles an hour! The Fairdown Straight seems to have come to life. It snakes towards him, gyrating and bobbing like the edge of a hula dancer’s hip.

The railway crossing sign at the end of the straight is suddenly a pneumatic windmill that’s being pumped up: bigger, bigger, bigger … Shit!

Brakes. Aaargh! Whoops. Not too many brakes. Speed likes time to slow down in. Sort of a democracy of speed: all the speeds between eighty and nought like to be recognised.

Now, a change down. Shit. Hope those cogs are strong.

Don’t take the S bend, just roll up the little dirt road into Woggy Watson’s cow paddock.

There, turn her around, don’t go in the ditch. Great. Return run. Now, WE HAVE LIFT-OFF! Eeeehaaa!

Royce, Royce, the people’s choice

Off down Fairdown Straight rolls Royce …

‘THIS YOUR CAR, is it, sir?’

Course it wasn’t his car, Harry Reynolds knew that. Knew exactly whose friggin’ car it was. Knew whose every car in the bloody district was.

‘Could I see your licence, sir?’

Could he shit. He knew that too.

‘Do you know what speed you were travelling at, sir?’

Christ, why do traffic cops always pretend you’re a complete idiot who’s been knighted?

There’d been a famous time when Harry Reynolds had stopped Bob Dodds:

‘You been drinking, sir?’ they said Harry said.

‘Yep.’

‘What have you imbibed, sir?’

‘Oh, a dozen pints of Miner’s, five or six whiskey chasers – had a bit of wine with lunch, too.’

‘Would you mind blowing into the bag, sir?’

‘Why?’ says Bob, ‘don’t you believe me?’

‘COULD YOU EXPLAIN the material hanging from the car, sir?’

And so Royce explained to Officer Harry Reynolds how he’d had this brilliant idea for drying his clothes by hanging them out the windows of Grant Franklin’s Anglia and haring off down the Fairdown Straight.

He told it to his mother later that day, and to Grant Franklin, and then over the phone to a pissed-off Linda Harvey. And then next day to Doddy Wold, who was going to be his lawyer, and a couple of weeks later to the judge who charged him with car conversion, excessive speed, dangerous driving and driving without a licence. All which got diverted into fifteen days’ Periodic Detention, starting the day he’d been going to score two tries against United and take Dana Glover to the clubrooms.

He’d walked to her place when they dropped him off the bus from the golf links. Her mother said she’d gone out with friends to the Doo Duk Inn, so he’d gone straight to the Gren and there she was, of course.

She’d been in a bit of a bad mood and told him he should have gone home and changed first, and that a prickle in his jersey had stabbed her in the arm. They’d had a desultory pash in the shed behind the Backpackers part of the pub, but then she said, ‘I’ve got my period, remember,’ and didn’t do a single ‘Oh Gordon’.