‘WHO PUT THE bloody butter in the fridge?’ bawled Dooley Morgan.

‘I did,’ said Bob.

‘Christ, it’s hard as the hobs of hell.’

‘There were flies all over it.’

‘Christ, Bob, flies don’t eat much.’

Dooley stumped past him and back into his office.

Bob Dodds made himself a cup of tea from Dooley’s Zip. Well, it wasn’t really Dooley’s Zip, in that it belonged to Sculley’s Fisheries, but in that the whole bloody wharf belonged to Dooley Morgan, you may as well say it’s his.

‘Where’s the spoons?’

‘None there? Shit. Bloody George will have pinched them for lures. Use a biro.’ Dooley’s voice was muffled with holding up his cigarette.

‘Bloody nunnery in here,’ grunted Bob. ‘None of this, none of that. Where’s Flag?’

‘Took the Typhoon out. Just to pump the bilge.’

‘Bloody needs it, too, when you see what comes out of that tub.’ Bob stretched the ache in his shoulders. ‘Christ, I’m tired. Something woke me up at five this morning.’

‘What was that then, Bob – Nadine?’

There was a bray of sound from the RT. ‘Shit, that’s Morrie,’ said Dooley. ‘What’s he doing out there?’

‘What’s the problem?’

‘Jackie Mosley’s out. If he sees Morrie he’ll probably ram him.’

‘Raid his pots again, did he?’

‘Yeah, came in last night with seven big crays, laughing like a drain.’

‘At least he’s the one bloody thief that rebaits them,’ growled Bob. He sat down in one of the big, bum-eroded dents in the sofa. Snow shone on the Paparoas through the window. Keeps the sea flat, does snow on the hills: and you need flat to catch flats. Three good days probably. ‘There’d be a ten-twenny high coming up, I reckon.’

‘Yeah, only a skinny bugger though. Might get two, maybe three days out of it.’

Then a northerly: snow goes, sea turns to shit.

The sea off Westport was no place to make a living, as far as Bob was concerned. Couldn’t get out often enough. And bugger-all there when you did get out anyway. His boat was not big or strong enough to get down to the Hokitika Trench for the hoki – just good for inshore trawling. Then if decent schools turned up, bloody Merlord sent a couple of big trawlers down from Nelson and scooped the lot. Had echo-sounders: could see the fish like they were in an aquarium – he didn’t have a shit show.

Used to be a man’s life; now it was a friggin’ accountant’s life. Fishing nowadays was just a sea of levies, deemed value fees, transaction fees, permit charges, lease prices …

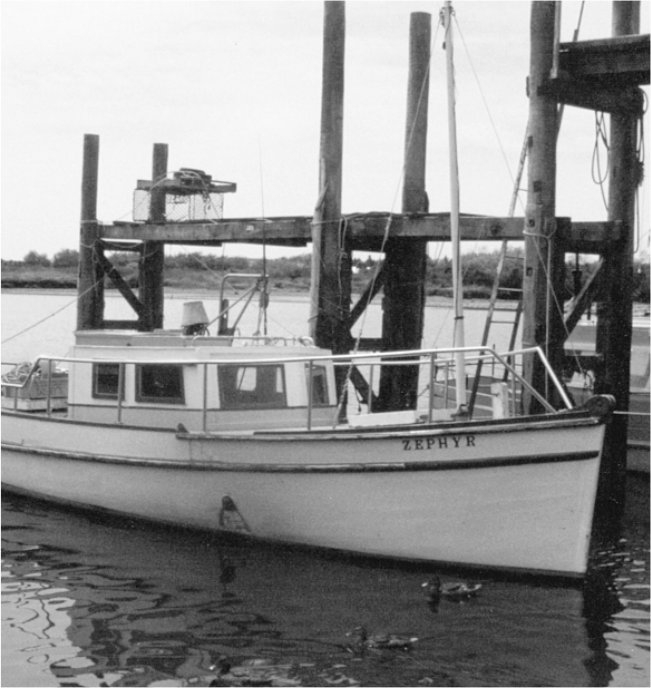

GEORGE WENT PAST the window on the Zephyr, standing on the little open wheelhouse of his sixteen-footer like he was Horatio Nelson on the Titanic … or something. Captain Calmwater they called him: he went no further than the half-mile training wall and put down little nets for kahawai. Jackie Mosley used them for baiting his crayfish pots; Morrie used them for re-baiting Jackie’s crayfish pots. Ha ha.

Interesting story, was the Zephyr. Mine manager, back in the early 1900s, wanted to build a boat. Had the carpenters take off the side of a coal bin – pure kauri – and replace it with beech. Built the Zephyr from the kauri. Coal-powered, of course. George had replaced the boiler with a four-cylinder seventy-five-horsepower Ford. Nice wee craft, the Zephyr, but no good on the open sea. Whenever he came in from his few forays George would jigger over the bar like he was pissed. ‘Captain Calmwater’s been done for DIC on the bar again,’ they’d all say.

The Cheryl Anne G was in: big red sixty-five-footer lying against the loading wharf. You could just see the interesting shape of Marjorie Shaw moving around in the weigh-shed beside the boat. Legs up to her ears and wore the jeans to prove it.

‘Unload the Cheryl Angie last night, Dooley, did you?’

‘Yeah. Hands so sore this morning I could hardly hold me dick.’

‘Get much?’

‘Thirty-three ton.’

They used to get sixty. The Cheryl Anne G was the only big hoki boat that came into Westport. All the others went into Greymouth, but she was a ‘cased’ ship – all the others were ‘binned’. You could get a thousand cases in the hold, whereas – because of the pointyness of its shape – you could only get three-quarters as many fish in polybins. You could case up on the ten-hour trip back from the Hokitika Trench so you were ready for unloading as you came into Westport. You unloaded at about ten ton an hour. If Dooley was on, you might get up to eleven.

He was a wonder to watch, was Dooley. He was so lazy that he’d re-invented work. If there was a way to make work physical-free, Dooley had found it: he was the most efficient bastard on the wharf. You watched others hauling and straining as they tipped the bins of fish – you watched Dooley and he was doing it with one finger, fag in mouth while he was non-stop talking to someone, maybe you. All the while there were forklifts coming back from the weigh-shed and screaming numbers at him: ‘1143’, ‘621’, ‘794’ … and he wouldn’t even stop talking, just nod. When he’d collected about a dozen of these weights in his head he wandered over to his office and wrote them down. He’d never got a weight wrong yet – though when you thought about it, how would you have known? Nah, the bosses would have known at the other end – they didn’t let anything get past them.

Dooley was ‘ships’ husband’ for Sculley’s, which was a fishermen’s co-op. Bob was part of it. They competed with the big guys – Merlord, Everest … the companies that dominated the fish industry and squeezed the raw prawn outa the little guy. Well – elsewhere, maybe. But in Westport the big guys didn’t have a shit show. Dooley pinched just about every boat that came over that bar.

He’d wander over, as a boat docked at Merlord wharf, find the skipper and say, ‘Merlord giving you four-fifty, are they?’

‘Yeah,’ the skipper’d say.

‘I’ll give you four-ten,’ Dooley would say.

‘Eh?’ the skipper’d say, staring at Dooley as if he hadn’t got both oars in the water.

‘Yeah, four-ten. (Pause.) And I’ll give it to you tomorrow.’

And that was the hook, see? Big companies had so many boats you often didn’t get your money for weeks. And fishermen were always broke. Ten minutes later that Merlord boat was docking at Sculley’s wharf.

The companies knew about Dooley but they reckon they were scared to try to arse-end him because he always had the oil on every illegal or unfaithful thing they’d lately done.

And he was keeping men in business, too. The big companies would fork out if a skipper was short for diesel for a trip, or they’d give them food chits to stock up for a big three-weeker. But then they had you. Zap. You owed money to Everest, then unloaded at Sculley’s, and they’d impound your boat.

So if any Westport boat-owner needed a loan they went straight to Dooley. He must have had something on the bank manager, too, because that loan always came through. Bugger-all other ones in the district did.

And so you busted your gut to pay old Dooley back.

‘HEARD A GOOD story the other day,’ chirruped Dooley, settling back in his chair, feet on the heater. ‘Not even dirty.’ Eyes as wide as pickled onions behind his specs as he set off: ‘See, this river in Canada had hooering big salmon – fat, juicy, tasty. But white. White bloody salmon – can you believe that? People’d open a can and say, “Fuck off, I’m not eating white salmon; salmon’s pink.” Serious case: they couldn’t sell the bloody stuff for love nor money. Tried dying it pink: no good. In the end they got in this famous ad man – “Million bucks if you can make this product saleable.” Well, he put his mind to the case – day in, day out – thinking about how to sell white salmon. Then he got it. He told them to put a certain slogan on each can, and after that, that white salmon sold like hotcakes. Know what the slogan said?’

‘Nah, wadd’d it say, Dools?’ slurred Bob fondly. (There was Johnnie Walker in Dooley’s cupboard under the tea bags.)

‘Said: “GUARANTEED NOT TO TURN PINK IN THE CAN”. Haw haw haw!’

GOOD OLD DOOLEY. He’d been born in Greymouth – though you never mentioned that. Left the district – left the country – and drifted around the world on boats. Spent a couple of years on purse seiners in Hawaii – only local ever to have done that. Bit of a legend because of that.

Bob found it interesting listening to him talking about how you did purse seining. You found the big shoals of tuna and got ahead of them, then lowered the aft launch, with net attached. It did a circle of the shoal, then joined the net up at the front of the boat. So there was a big mesh fence dangling around the shoal. Then you pulled the bottom ends of the fence together like a big purse. Hence the name.

Of course that left a big hole the fish could escape through under the boat, because the net was attached fore and aft, with nothing in between.

So you had these things called tuna bombs – little hand grenades. And some of the crew sat on the net side of the boat, with Cuban cigars, lighting tuna bombs and scaring the fish away from the gap under the boat. Great days. Sitting there smoking and bombing …

Dooley told the story of one of his purse seining mates who was staying in the penthouse of a flash hotel in Honolulu and lit a tuna bomb, biffed it down the dunny and flushed. Was about halfway down the pipes when it went off, and blew out every crapper in the building. Haw haw!

Great story, but you never quite knew with Dooley.

HE WAS A great guy, Dooley, and they’d been going to put his name forward for one of those New Year’s OBEs, or DSMs, or something – for services to Westport fishing – until someone had pointed out that half what Dooley did was against the law and he’d probably end up wearing his friggin’ gong in jail.

So they didn’t nominate him. And the gongs kept going to the people who broke the other half of the law.

But it was true: without Dooley, the sea off Westport wouldn’t have earned you a pauper’s wage.