THE BLACK SHEILA – Betty – did a friggin’ runner with the fish. Dooley had known she might. She’d bribed that air-headed bloody Marjorie Shaw into giving her an FLD. Five hundred American fuckin’ dollars she’d paid for it. Mind you, no use getting too far up yer high horse; everyone’s amenable to bribery. He’d’ve probably given her an FLD for $US500 as well. And thrown in a Fish Transport Docket as well. Just like bloody Marjorie Shaw had.

Human nature, that was the trouble. She needed help, and human nature being what it is, that help got bought. Probably bribed Ray Hill to bring a truck down, forklifted the coffin into the back, and off. Or someone else as greedy as Ray. Which was anyone with a bloody truck. Headed for Nelson or Christchurch probably – he’d phoned both ports. And both airports. A 700-pound tuna in a fish-tail coffin shouldn’t be that hard to find.

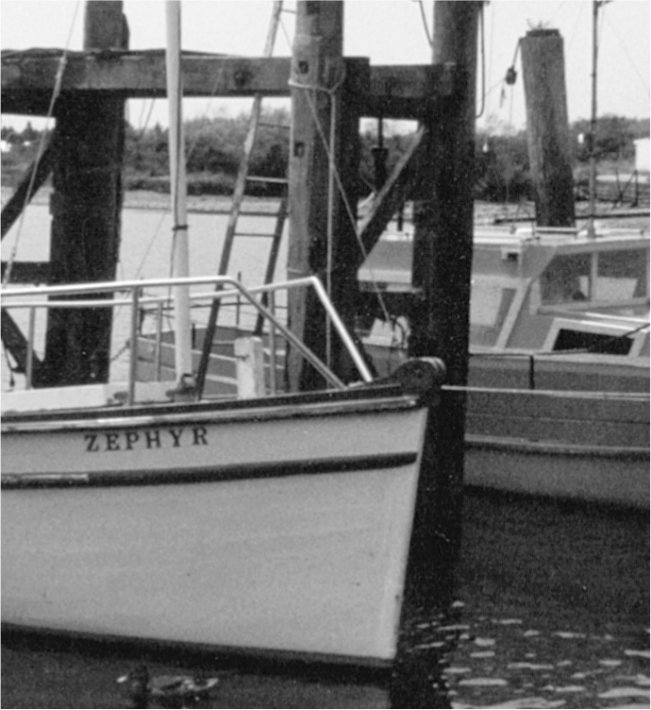

OLD CAPTAIN CALMWATER’S boat wasn’t insured, of course.

‘Nae need, Dooley,’ ole George used to say. ‘Built leek steel: hearrt kauri. Th’ knew hoo ta build vessels in those dees. An’ if she do sink, ee’ll be own er, so wha’ weel ee care?’

He, of course, wasn’t insured either.

Fact of the matter was, the stern of the Aurora bunted the Zephyr fair on the stem. Popped the strakes out of the rabbets clean as a whistle. Every last clinker plank – from the wale down to the garboard – burst open. Down she went in moments. Oh yeah, they sure knew how to build boats in those days. Not a dent in the kauri, of course. There it was, sitting on the bottom of the bloody Floating Basin, every plank as good as new.

How had it happened? Kid denied all knowledge. Marjorie Shaw sort of backed him up. Said she’d gone back to the Aurora with him – ‘just to make sure he made it without drowning,’ she reckoned. Yeah, maybe. Who knows what really happened? But she reckoned nothing. Did he start the boat up? he’d asked her. No, she’d said. Probably true. Hell, you didn’t get Marjorie Shaw on board, then start messing around with engines. There’s better things to mess around with.

But maybe he’d wanted to impress her? Show off? Prove what a big-shot fisherman he was: ‘You wanna see me drive this boat, Marjorie?’

Well, she reckoned he hadn’t and he reckoned he hadn’t, so who knows?

Who else could it’ve been? Best bet was the fishnapper, Betty. If two big things happen at once, it’s more logical to combine them than to look for two separate causes. Had she been gonna set off in the Aurora with the fish? Maybe take it back out to the squiddies? That would certainly be the best way of getting it back to Japan. Which’d be the logical place to take it – biggest fish market in the world, in Tokyo Bay. Must be worth something if she’d pay 500 Yankee bucks for a landing docket.

Yeah, that could be it. She’d been slipping outa the moorings with the fish when she’d backed into the Zephyr. That was it. Pranged up, kid so shickered the hit didn’t wake him. She goes into Plan B: got hold of Ray Hill or someone, headed off to God knows where …

Yeah, that was it. Small matters like how had she got the fish onto the boat – and then off again, and what had she intended doing with the kid etc, came into his mind, waited to be answered, and were shooed away again by Dooley’s inclination. He hadn’t trusted Betty from the start, and he’d been right. There the matter rested as far as he was concerned.

OLD GEORGE DIDN’T take it out on the kid. Why not? Bob wondered. Here he was, the major suspect in the sinking of the Zephyr, and bloody old George believed him. This friggin’ kid had a charmed life! Royce said he’d come on board, crashed in a pissed stupour and not woken till Bob’d doused him in the morning, and Captain Calmwater believed him. Only dent in Royce’s story was he’d missed out the bit about Marjorie coming on board with him. But then he’d looked totally shocked when this bit of information was mentioned. Could well be he was so mullocked he didn’t know. Might even have had his way with her without remembering. It’d be typical of him. Can shag women in his sleep, the lucky little bastard.

George had rung Bob at around half past seven in the morning, in an agitated state. He’d gone down to get the tide out to the training wall for kahawai and his boat wasn’t there. Then he’d seen it through the murk, sitting on the bottom of the lagoon next to the Aurora, with a broken bollard floating above it, still tied to the mooring rope.

The kid had been a total mess. Bob’d had three goes at waking the bastard before he threw water in his face. He’d reckoned he’d known nothing about Marjorie Shaw, and she reckoned she knew nothing about him until Bob’d produced this little silver-grey purse he’d found by the wheel. This is what made Marjorie fess up to having been there – because the purse was bursting with US dollars. ‘Okay, if you weren’t here, this isn’t your purse,’ he’d said to her; ‘better get it down to the cop shop, eh?’ ‘All right, I was here,’ she hissed. ‘Now gimme the purse.’ But she still reckoned nothing had happened between her and the kid; she’d just seen him home, then gone. She must have got distracted when he fell down the ladder and forgotten her purse, she said. All of which may or may not have been true, but then sexual shenanigans weren’t the point at issue. The point was: the purse was found beside the wheel, so why had they been standing there? So the kid could start the motor? They both said no. Bob had been in two minds until George had absolutely believed the kid, and then Bob had gone with the mind that said it wasn’t him. Bob knew of about fifty bad things the little arsewipe had done, and he’d promptly confessed to every one of them, so statistically it was likely he was being honest this time. Statistically, in fact, he was probably the most honest person Bob knew – he had so much to be friggin’ honest about.

So overall, the kid hadn’t done it.

So who had?

From somewhere came a mental murmur of Sticky. With it came a tang of unfairness – hell, there was absolutely no evidence, and Sticky, overall, was a decent sort of bloke. But he wasn’t himself. And he wasn’t himself because of this kid. This kid’s doings had driven him nuts.

Could be a bit of revenge going on: Sticky sees the kid shambling back with Marjorie Shaw, and that would set him off big time – here’s the kid scoring yet another woman after messing around with Sticky’s. He waits until they’ve done whatever they did, waits until Marjorie sets off home, skids on board, starts up the motor, puts her in reverse and scarpers. Bingo, down goes thirty grand’s worth of uninsured vessel.

Kid carries the can whether he did it or not. He was on board; boat was in his charge. They’ll probably refloat the Zephyr; probably restore it. But the cost will come outa the kid’s hide for the next twenty years.

And suddenly, there was Sticky! Sauntering down the wharf, hands in pockets, radiating that total innocence that made you just know he was guilty.

‘Heard about the accident,’ he said.

‘That a fact, Sticky?’ purred Bob. ‘Mind telling me how you heard?’

Sticky gave that pause that was like drawing your hand back for a straight right. ‘It was on the wireless, Bob.’ And he smiled about sixteen teeths’ worth of happiness.

Shit. He was probably right. Both cops and the traffic cop were down here, and so were the harbourmaster and various Marine Department and council flunkies as well as the big serious Westport News reporter they called Scoop. Bloody TV was probably on its way over from Christchurch.

‘You’re looking very cheerful for a man without a job, Sticky,’ said Bob.

‘Heading up to Nelson, Bob. Might lease out the Normandy and do a season of scallops.’

‘Might just look a bit as if you’re running away, Sticky.’

‘Got nothing to run away from, Bob, you know that.’

‘How would I know that, then, Sticky? Eh? Look, old George’s over there, mourning his vessel. Why don’t you wander over, look him dead in the eye and tell him where you were early this morning?’

‘I really don’t think George would be interested in where I was this morning, Bob. Might be more interested in what the kid was doing, eh? Like having nookie with other people’s women and sinking other people’s boats.’

‘You seem to know an awful lot about it, Sticky. You hear that information on the wireless too?’

‘I get my information from a far more reliable source, Bob – Dooley Morgan.’

‘When you heading to Nelson?’

‘This afternoon.’

‘Just cast your eye over the back seat before you set off, check there’s not a 700-pound fish in there.’

He looked deep into Sticky’s faded, tawny eyes. There was no surprise in them. ‘Yeah, I heard you’d lost the kid’s fish. All them people deprived of the joy of looking at it, eh, Bob? All them trophies you’re not gonna get.’

Suddenly Bob had a conviction. That tuna wasn’t on its way to any far-flung fish market somewhere; it was at the bottom of the Buller River, weighted down with a railway wagon wheel or something.

‘You took that fish, you shitbag,’ he growled. ‘Outa sheer bloody-mindedness, you pinched it and biffed it in the river. Well, it’ll rot and float soon enough, and if I see so much as a morsel of it, I’m coming after you.’

‘You know, Bob,’ replied Sticky airily, ‘I remember my days of dredging the berths around here – say, right under where the Buller Lion is right now – and the thing I most remember is the incredible number of eels we used to suck up. Water around this harbour must be about fifty percent eel, I’d say, Bob. Big carnivorous eels.’ He turned to leave.

Bob called after him: ‘Which did you do first, Sticky – sink the Zephyr or the fish?’

Sticky gave a wave with the back of his hand.