‘I took the afternoon off [from school] and went to the veterinary college for a consultation with the principal. He said I would be O.K. going in without any Science as they taught all that was necessary there.’

Alf Wight, diary, 28 April 1933

ALF WIGHT TOOK the Corporation tram car across Glasgow to Hillhead High School on 3 September 1928; in more ways than one, he was going up in the world. The Hillhead area in the West End of Glasgow is aptly named. Geologically, it is a series of post-Ice Age clay deposits forming a series of small hills or ‘drumlins’. On top of one of these drumlins sat Hillhead High School; from the school’s windows the view was all downhill to the flatness of the Clyde riverside three miles away.

Hillhead was a shining example of the adage that the rich people live on the hill; since the 1850s the area had been one of Glasgow’s most fashionable suburbs, following the exodus there of the middle class from the inner-city’s smoke and poverty. They went westwards, as the better off did in every British city, to avoid the prevailing west to east wind blowing the diseases of the poor over them. By the turn of the nineteenth century, 80 per cent of Hillhead’s residents were the professional classes, many of them employed in the neighbouring university; most of the rest of the inhabitants were their servants. To tempt the migrating bourgeoisie, canny property developers built honey sandstone tenements and terraces of Greco-Roman elegance; some of the tenement flats in Hillhead contained ten rooms. Visitors to the leafy streets and green spaces of Hillhead were reminded of Bath. Unlike roker, with its industrial din, Hillhead was a world of church quiet, interrupted only by the rustle of leaves and the occasional hansom horse cart. In Hillhead, children played in gardens; when they did play on the street, they did so in muted games of hopscotch and skipping to polite songs, such as Glaswegian William Miller’s famous ‘Wee Willie Winkie’.

Opening on Monday 13 April 1885, Hillhead High School stated its educational aspirations in stone. A forbidding four-storey building fronting Sardinia Terrace, Hillhead High School promised those about to pass through its gates (with separate gates for boys and girls) Calvinistic hard work; indeed, the building was built almost to the parameters of its street-corner plot, leaving small recreational space for its pupils. Inside, the building overran with austere classrooms, so many of them that headmasters numbered the rooms so that they, let alone the pupils, did not get lost. The school’s motto was that of the Burg of Hillhead, Je Maintiendrai (‘I Shall Maintain’), an oath promising to keep high standards of industry and discipline. But the grandiose Doric and Ionic classical columns on the building’s façade, the portico, and the date of construction in Roman numerals – MDCCCLXXIV – advertised the importance the school attached to the making of gentlefolk. As the school’s official history put it, the first headmaster, Mr Edward Macdonald, ‘made his School a centre of learning; but he was still more intent on making it a building place of character, a training-ground for his pupils to fit themselves for the duties, responsibilities, and privileges of citizenship’.

Hillhead was self-consciously modelled on the English public schools and had accordingly suffered an extraordinary toll of its old boys in the Great War, only a decade before. In the axiom of the era, an officer was a gentleman who had attended a fee-paying school, and an officer had the most dangerous job in the trenches of the Western Front; leading the men over the top. No fewer than 178 Hillhead alumni had died in the 1914–18 conflict. The school’s Officer Training Corps continued to be active, as were all the societies that public schools commonly enjoyed, from a debating society to a literary society to a drama club.

Sport was also an essential component in building the character that Edward Macdonald and successive heads wanted. Initially the cramped confines of the Sardinia Road site restricted sports to cycling and running – both of which could be done on Hillhead’s roads – and Physical Training with moustachioed Colour-Sergeant William Walker, late of the Northumberland Fusiliers. The quintessential public and grammar schoolboy team games of rugby and cricket – soccer being regarded as suspiciously ‘infra dig’ in such circles – had to wait until the renting of a pitch at Glasgow Agricultural Society’s showground at Scotstounhill.

Tucked away on the curriculum was the all-important lesson in the making of a gentleman: Elocution, twice a week. Later in life, Alf would refer to his own voice as ‘glottal Clydeside’; maybe it was so when he first walked, wearing his cap, blazer and shorts, through Hillhead’s boys’ gate, but it wasn’t when he left. It was a soft Scottish burr, refined at Hillhead. (Elocution lessons, unintentionally, did Alf the nascent writer a favour. By drawing an attentive ear to dialect, speech patterns and rhythms, it actually made them easier to reproduce. So when Alf transmogrified into James Herriot and wished to reproduce the dialogue of Yorkshire farmers and characters, he already had his ear in.)

In the Second City of Empire, only Glasgow High School rivalled Hillhead for its academic standards. A report by the Scottish Education Department in the summer of 1928 found that Hillhead’s head of modern languages was ‘outstanding’, while the teaching of Latin was ‘excellent’ (a knowledge of the Classics being a sine qua non in the making of gentlemen and gentlewomen), Maths of ‘a very high standard’, and English ‘thoroughly sound’.

Hillhead’s list of literary luminescence did not end with Herriot. The future Daily Express editor Ian McColl – who 50 years later would serialize Herriot’s books in his newspaper – was in the same class. Bestselling author Alistair Maclean also attended from 1937 to 1939. And perhaps a brighter star still in Hillhead’s firmament was Robert W. Service, the ‘Canadian Kipling’ and the ‘Bard of the Yukon’, who had been a pupil in the 1880s. Service’s ‘The Shooting of Dan McGrew’ is probably the best-selling poem of all time. Service wrote in his autobiography, Ploughman of the Moon: An Adventure into Memory, that ‘At home it was a struggle to make frayed ends meet, yet each day we trooped off to what was then the Finest School in Scotland.’ Forty years on, Alf Wight also set off to the fine school from a home worried by money. Most of the boys and girls were from very well-off homes on the doorstep, but there were others like Alf whose parents were hard pushed to pay the bill for the school on a hill.

It was quite a bill. When Alf started at Hillhead in 1928, the fees were £2-10s-0d a term; in April 1930 the fees were raised to £2-16s-0d a term so that the school could build up its clubs and societies. On top of the basic fees there was all the uniform, kit and caboodle to pay for: a boy’s navy all wool blazer, with ‘HHS’ badge, cost 14/6d from Hoey’s (‘For Value’) at 449 Dumbarton Road, or 18/6d for the tailor-made version; a cap with badge was 2/11d; the striped school tie 1/6d. If Alf’s parents had been tempted to shop for school colours at Rowans on swish Buchanan Street, the prices were grimacingly expensive: a basic blazer was 21 shillings, a cap was 3/6, stockings (long socks to wear with shorts) were 2/6, a tie 2/6. A pair of ‘Anniesland’ rugby boots was 19/6d. In 1930, Alf’s second year at Hillhead, his parents would have spent around £13 in fees, uniform and extras.

And this at a time when the Depression was raging. By April 1930, the number of shipyard workers on the Clyde had dropped to 29,000; in 1931 the most vivid proof of the Clyde’s shipbuilding troubles came at John Brown’s yard with suspension of work on the Cunard liner Queen Mary, the biggest ship in the world. A year later 125,819 people were unemployed in Glasgow. Porage and thin soup became the sole diet of thousands of the city’s children, who would forever bear the mark of deprivation in stunted growth. But even those who had work found things tough; following the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the average wage for a 47 hour week for a tradesman in Britain fell to £2-4s-0d. Even when Pop was in work, he was earning less.

If the modesty of his Yoker background affected Alf Wight, he hid it well. Or, more likely, it simply did not bother him. Photographs of Alf in school uniform show a boy with an unfailing smile. In the privacy of his diary, Alf wrote about Hillhead: ‘Of course school in some of its phases is an excrescence on the face of the earth – getting up at 7.45, homework, etc, but nevertheless there is something about it which makes it OK.’ What made it OK? Larking with friends was one thing:

My face is pretty sore tonight having been the target for a great number of snowballs during the course of the day. During the dinner hour, we had a great scrap on the hill behind the school – the janitor, who is an officious wee man tried to stop us but retreated in disorder under a veritable barrage of snowballs. Oh, it was great to see him trying to be dignified and then beating it for dear life. I had a few skirmishes on the way to the car [tram] and I spent the evening trying to absorb a spot of knowledge in readiness for the forthcoming exams.

Then there was football at lunchtime. ‘Our dinner-hour would be torture without our wee game of footer,’ he told the diary. When the dreaded janitor stopped the playing of football at lunchtime because of a broken window, Alf bearded the lion in the den by going to the headmaster himself and asking permission to play. ‘I got it and was a popular hero in consequence.’

Alf’s enjoyment of school was doubtless aided by the fact that he was conspicuously clever. And what he didn’t find easy, he worked at. Alf Wight, like his parents and grandparents, was a worker. ‘There’s no doubt about it – work is the thing to produce happiness,’ he wrote in his diary. Placed in Form IC, Alf studied eight subjects in his first year: Science, Drawing, French, Maths, Latin, Geography, History and English. From the outset, Alf was markedly good at English, achieving 72 per cent in his end of year exams, his best subject along with Latin. His second-year report card described his progress as ‘Very Good’, a step up from the ‘Good’ of IC. He excelled at French, English and Latin – he later mused that he read so much Virgil, Ovid and Cicero at home on Dumbarton Road that he ‘could have carried on an intelligent conversation with an Ancient Roman’. In his Intermediate Certificate (the Scottish equivalent of modern GCSEs) at the end of Form III, his performance was so outstanding that he was declared the school’s Intermediate Champion, the academic crème de la crème.

Although James Herriot would unaffectedly describe himself as ‘just a country vet’, he long had an alter ego that was a wordsmith, and at one early stage of his school life definitely harboured a desire to be a journalist. He read ravenously: Sir Walter Scott, John Buchan, H. G. Wells, Rider Haggard, G. A. Henty, and bought the complete works of Milton from a book barrow in Renfield Street for ‘a bob’. Pop was smoking Kensitas cigarettes, and with the coupons Alf sent off for a 14-volume set of Dickens in blue hard-covers. With another 350 Kensitas coupons – in the style of the time, Pop must have been smoking like a Clydebank chimney – Alf secured the complete works of Shakespeare. Also on Alf’s reading list was American short-story writer O. Henry (‘that man’s a joy to read’), Gothic detective novelist Wilkie Collins, and even Thomas Macaulay, the highbrow Victorian essayist and historian. He enjoyed Edgar Allan Poe, though only in small doses, because too much Poe left him feeling depressed and morbid afterwards. (‘I read some of Poe’s queer, queer yarns. That chap must have spent all his time sitting thinking till his thoughts twisted themselves into strange shapes.’) His indispensable reference source was Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopedia; he kept his set of volumes all his life, and even read bits to his grandchildren. The books now sit on the shelves of the sitting room in The World of James Herriot museum in Thirsk, in the house that was the original for Skeldale.

But Alf’s favourite author as boy and man was P. G. Wodehouse, the creator of Jeeves and Wooster. One doesn’t need to be a Sherlock Holmes of the page to see some of the fingerprints of Alf Wight’s boyhood reading on James Herriot’s adult writing: the perfect narrative compression of O. Henry (the Herriot books being, if one cares to think about it, composed of loose-linked miniaturist autobiographical tales), and especially the comic heightening of character of Wodehouse. Both Siegfried and Tristan would be perfectly at home in a Wodehouse tale.

As a diarist, Alf was naturally enough interested in the master of the genre. After a visit to the public library at Whiteinch next to Yoker, Alf wrote in his journal:

While I was there [in the library] I saw a volume of Pepys’ diary which interested me as I am emulating him through this tome. I think I’ll begin each day with ‘Up betimes and did go to the institution’.

Alf’s diary was not the usual angsty teenage confessional or bare aide-memoire; it was like Pepys’ journal – a full record of his life, particularly in 1933. He also wrote the diary, not kept it. Some of his enjoyment of words is evident in a note about ‘school and its appurtenances’:

For English we have Mr Barclay [‘Big Bill’] who is large, and at times, genial. I like him. For Latin we are in the care of Mr Buchanan [‘Buckie’] whom I can’t make much of. He is aged, tall, unhandsome and rather frail … at times I think he’s not bad and at times he gives me a pain in the neck. Mr Clark [‘Brute Force’] who is small, dapper and likeable takes us for maths and Miss Chesters [‘Soppy’] endeavours to pump French into us. Chesters is frank and almost boyish – I like her very well. Twice a week we get Mr [‘Tarzan’] Brooks for Elocution. This bird, tho’ probably well meaning is nothing but a funiosity.

Alf’s ‘elocuted’ ear for speech is clear in his recording of Buckie’s droning on about the need for the class to work harder for the Highers: ‘Ah’m tellin’ ye, ye’ve no go’ a ghost o’ a chance o’ getting your Higher Latin – it takes students tae get it, no a lot’ o’ flibberty, gibberties like you.’

When Alf was 12, and still in his first year at Hillhead, there bounded into his life a character that would fix its course. Don was a Red Setter dog, given to Alf by his parents, partly as a reward for passing the entrance exam to the school. Although Alf already had pet cats in the apartment, a dog was different, more companionable than the solipsistic felines. However, as Alf found, the Red Setter (aka the Irish Setter) has certain drawbacks as a household pet, due to its gundog breeding. A genetic pot pourri of Irish Water Spaniel, Gordon Setter and Pointer, the Irish Red Setter was bred for brains and endurance, the latter quality requiring a lengthening of the leg. At 27 inches high and 70 lbs in weight, the Red Setter was a big dog for a small ‘hoose’ in a tenement. Worse, Don’s intelligence combined with his desire for activity meant he quickly got bored. And when he got bored, he became destructive. More than once, Don caused mayhem in the apartment at 2172 Dumbarton Road. He also ran off. Often.

7/2/33: Don ran away tonight, the rascal, and hasn’t returned – he’ll be for it when he does.

15/2/33: Don ran away from mother tonight and has just arrived, very penitent and sorry for himself. He’s a scream when he’s in that condition – tail between his legs and rolling eyes – a picture of dejection.

21/2/33: I had to bath Don today as he ran away from Sadie and paid a visit to a particularly filthy field and returned smelling like a cow-bire.

For Alf these negatives of Don’s were outweighed by the positives of the breed, which Don, ‘lean, glossy and beautiful’, had in abundance. Since Red Setters are used to close co-operation with humans, they are boundlessly affectionate, innately good-humoured and thoroughly responsive. A dog is a boy’s best friend. Maybe especially so when it is a Red Setter.

On one occasion, at least, Don was put out to stud. Alf wrote in his diary on 12/2/33: ‘Our Don has become the father of 11 thoroughbred Irish Setter puppies and so my reason for going to Hardgate was to see them. They were great wee things. Fat as barrels and squeaking away like anything.’ Alf gave one of the pups to his friend Curly Marron, who lived in the same tenement block, and who had been a loyal companion on walks with Don. Curly christened the pup Rex. Soon after Rex became ill, teenage Alf dosed him with castor oil. This did little to cure Rex, and Curly’s mother and sisters became terrified by the puppy’s ‘frequent outbursts’ and wanted rid of him. Alf said the dog should see a vet. The vet said the illness would pass in a day or two. And, much to Alf and Curly’s relief, it did. With Don at his heel, and sometimes Rex and Curly, sometimes with other friends and their dogs, Alf walked along the canal, along the ‘Boulevarde’ (Dumbarton Road), but also regularly tramped out into the countryside at the top of Kelso Street.

There were expeditions further afield too. ‘Living in the extreme west where the city sprawl thinned out into the countryside,’ Alf recalled in James Herriot’s Dog Stories, ‘I could look from my windows on to the Kilpatrick Hills and Campsie Fells in the north and over the Clyde to Neilston Pad and the hills beyond Barrhead to the south. Those green hills beckoned to me and though they were far away, I walked to them.’ Those green hills were at least 15 miles away but he walked to them often. ‘I spent the whole day,’ he wrote on 25 June 1933, ‘in a tramp to the Whangie & over the O.K. hills with Jimmy [Turnbull] & Jock Davy. It was simply wonderful.’

On the repeated road to the hills, Alf had a change of perspective. Hitherto he had been a city boy. Somewhere in those green remembered hills around Glasgow, he became a country lover.

Something else happened to Alf out in the scented, intoxicating Lanarkshire hills. Watching Don and the other dogs romp and run, Alf realized that he was intrigued by the behaviour of canines – and that he wanted to work with dogs, rather than with words. He did not abandon writing, but the animals had begun trumping the words.

The light-bulb moment came when Alf was 15 (he tended to misremember it as 13), when he read an article in Meccano Magazine’s ‘What Shall I Be?’ series entitled ‘No. XXVI – A VETERINARY SURGEON’, by G. P. Male, President of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons, in December 1931. Male wrote:

Veterinary surgery is one of the few professions in which the number of entrants has shown a considerable decline in recent years. This decline is probably due to the belief that the expansion of motor traffic and similar changes have reduced the prospect of success in the profession. The belief is a mistaken one, however, for the decline in the importance of the horse is being at least partially counteracted by a growing demand for the services of the veterinary surgeon in other directions. The prospects of those now entering this comparatively neglected profession are bright, particularly if they approach it with a real liking for animals and for the open-air life that it entails.

As Alf read, he ‘felt a surging conviction’ that veterinary medicine was the career for him. ‘As a vet, I could be with dogs all the time, attending to them, curing their illnesses, saving their lives.’ The conviction that his destiny was to become a dog doctor was cemented by a visit to Hillhead High from Dr A. W. Whitehouse, the principal of Glasgow Veterinary College. Like Male, ‘Old Doc’ Whitehouse refused to believe that the veterinary profession was on its last legs because of the motor car and the tractor, and went to Hillhead as a convinced recruiter for his occupation in general, his college in particular. He told the assembled pupils, Alf recalled later, ‘If you decide to become a veterinary surgeon you will never grow rich but you will have a life of endless interest and variety.’

One boy, at least, was persuaded by Dr Whitehouse’s evangelizing. Henceforth, Alf Wight knew exactly what he wanted to do with his life. But the obstacles, he realized, were enormous. Veterinary science was, well, science, and Alf Wight was, in his own words, ‘certainly not a scientific type’. He had already chosen to specialize in Arts subjects over science at school, and with his ‘Highers’, the Scottish equivalent of A-levels, already on the horizon he could not swap midstream. So the 15-year-old Alf Wight went up to Glasgow Veterinary College on Buccleuch Street to seek Dr Whitehouse’s advice. Years later he wrote:

He listened patiently as I poured out my problems.

‘I love dogs,’ I told him. ‘I want to work with them. I want to be a vet. But the subjects I am taking at school are English, French and Latin. No science at all. Can I get into the college?’

He smiled. ‘Of course you can. If you get two higher and two lowers you have the matriculation standard. It doesn’t matter what the subjects are. You can do Physics, Chemistry and Biology in your first year.’

But one anxiety still gnawed away. Alf Wight was poor at Maths. Would he, he asked Dr Whitehouse, need Maths to be a vet? The old veterinarian laughed, and replied, ‘Only to add up your day’s takings.’

With his career goal set, Alf Wight worked harder still at school. With the tutoring and encouragement of English master ‘Johnny’ Gibb, Alf counted among his triumphs in the fourth form the winning of the prize for English. A poem, authored by Alf and ‘DMM’, appeared in the December 1932 issue of the school magazine. Entitled ‘Four o’clock’, the poem is a parody of Thomas Gray’s Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard from 1751:

The buzzing bell doth screech the ended day,

The toil-worn herd winds slowly home to tea;

The teachers homewards wend their weary way,

And leave the School to ‘jannies’ big and wee.

Now fades the fog-bound landscape from the sight,

And all the School a solemn stillness holds,

Save where the cleaners sweep with all their might

And clanging pail the hidden dirt enfolds.

Save that from yonder smoothly swinging doors

The moping ‘jan’ doth audibly complain

To such as playing football after hours,

Infest his all too desolate domain.

The icy blast of cold and frosty morn,

The ringing of alarms beside their head,

The milk-boy’s skirl, the matutinal horn

Will tear them, on the morrow, from their bed.

Six months later, another poem by ‘JAW’ appeared in the Hillhead High School Magazine: this time the target of the schoolboy spoofing is Hamlet’s ‘Angels and ministers of grace defend us!’ soliloquy, spoken by the prince when he first sees the ghost – and calls upon all things holy to protect him:

Angels and ministers of grace defend us!

Be thou a verb, a noun, an adjective,

Come thou from Virgil, Livy, Cicero

Thy object, or to help or hinder me—

Thou comest in such a questionable shape

That I will guess at thee: I’ll call thee Noun,

Pronoun, Conjunction – anything! Oh! Answer me!

Let me not burst in ignorance; but tell

Why the examiners, fiend e’en though they be

Do thus maltreat me; why the dictionary,

In which thou hast been quietly inurn’d

Hath ope’d his ponderous and gilt-edged jaws

To cast thee up at me. What may this mean

That thou, foul word, so tangled, and unreal,

Revisit’st thus the examination room,

Making day hideous; and me befooled,

So horridly to shake my disposition

With thoughts beyond the reaches of my soul?

Say, why is this? Wherefore? What should I do?

Ironically, it was Alf’s very ability at English that led him into trouble at school. For three years, his Maths master, Mr Filshie, had tolerantly shrugged his shoulders at Alf’s regrettable mathematics, the nadir being 5 per cent in a trigonometry exam. When Alf won the Intermediate prize, followed by the English prize, Filshie suddenly woke up to the fact that Alf Wight was a very bright boy. ‘Wight,’ Filshie boomed one day, ‘I have always thought you were just an amiable idiot and have treated you accordingly, but now I see that you have come out top of the class in your English paper, so I can only conclude that you have not been trying for me. Hold out your hands.’ Six of the best on Alf’s palms followed. (Unlike English schools, which used the cane for punishment, the leather strap or ‘Lochgelly tawse’ was the common means of inflicting corporal punishment north of the border.)

By 1932, Hillhead High School had moved from its pinched confines at Sardinia Terrace (since renamed Cecil Street: the old school building now houses Hillhead Primary) to a new site three streets away on Oakfield Avenue. So popular had the school become that the governors’ constant sub-dividing of rooms was no longer a solution acceptable to the Education Department, which threatened to take away the school’s grant. Given Hillhead High School’s social aspirations, it must have pleased the governors no end that the Oakfield address lay opposite Eton Terrace, which had been designed by one of Glasgow’s greatest Victorian architects, Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson. Thomson, for his part, probably revolved in his grave as the new Hillhead High rose from the mud of the drumlin. In the reverse of the usual construction industry scenario, the school cost less than the estimate (by half, of a given figure of £183,000) and the budget for architects Messrs. Wylie, Shanks and Wylie must have been particularly skimped on. With its awkward back-to-back Y shape and its red bricks, Hillhead High School hardly boasted perfect Classical proportions. Still, when the 736 senior pupils moved in on 1 September 1931 they most likely marvelled at the echoing spaces of the two gymnasia, the hall with a stage, the art rooms, laboratories, library and refectory. However, despite the change in location and the greater space, the round of school life continued as before: there was the Armistice Day service in Belmont Church, the march past the War Memorial on the first school day after Remembrance Sunday, the Christmas holiday, ‘skating’ days off when it was really icy, the holiday on 26 May to celebrate King George V’s birthday, the annual summer garden party and half holiday in June, the end of year speech day in the Woodside Hall in July, cricket in summer, rugby in winter…

Sport was one of the aspects of school that made it rather more than ‘OK’ for Alf. He had a medal to hang around his neck for coming second in the Inter-Scholastic sports under-16 broad jump, and in his final year his prowess with a cat-gut racket saw him in the school tennis final. He also made the rugby Second XV. Hillhead was a die-hard rugby school, and during Alf’s time there it contained a clutch of boys who would go on to play club rugby, even to represent Scotland in the sport of the oval ball. Alas, Hillhead Second XV endured a string of defeats caused by a phenomenon known to every schoolboy rugger player. On losing to Kilmarnock High, Alf entered in his diary: ‘We were beaten but not disgraced as the other team was made of huge bruisers – six footers to a man.’ Another match: ‘I’m sorry to have to say we were beaten this morning and no wonder, as the Shawlands chaps were six footers to a man.’

When not in school, Alf’s life as a teenager was, like his life as a small boy, a round of hobbies, of making stuff and doing things. Since television was in its infancy and only available in one house in a thousand until the late 1930s, the only ‘on tap’ entertainment in the home was the radio. The first Scottish studio of the BBC opened up at 202 Bath Street in 1923, and making crystal radios to receive transmissions became a mad craze, much to the annoyance of the General Post Office (GPO) because hundreds of Glaswegians stole the earpieces from public phone boxes for their home radio sets.

The Twenties and Thirties are thought of as the hobbies decades for good reason: the school-leaving age had been raised to 14. To help children – and the children’s parents – pass all the weekends and holidays of the school year, publishers galore issued comics and tomes with advice on rewarding hobbies. Modern Wonders for Boys, a book published by Glasgow’s The Sunshine Press in the mid-Thirties was typical of the ilk, with articles on painting on glass, simple apparatus for the amateur conjurer, photography, stamp collecting, poker work, DIY winter decorations, making a bookshelf (there were legions of boys knocking up bookshelves in the Thirties, among them J. Wight, junior), getting the best out of cricket, as well as, ambitiously, ‘How to Make a Simple Canvas Canoe’.

But hobby books were about more than time-filling, they were regarded as tools for education, thus were peppered with general knowledge articles. Modern Wonders contained informative pieces on aeroplanes (always a winner with Thirties boys), clocks, the Seven Wonders of the World, glass-blowing in Venice, hoovers, electro-magnets, ships through the ages, signalling, submarines, X-rays, wild ponies of Britain, spiders, newspaper presses, coal mining … To sugar the educative pill, Modern Wonders filled the intervals with breathless fictional tales of derring-do (explorer Professor Ward in ‘The Last of the Lizards’) and schoolboys having wholesome fresh air adventures tackling foreign spies.

Save for not tackling dinosaurs and thick-accented German agents, Alf managed a full gamut of pastimes. He took Don for a walk every day, often twice a day (‘Of course Don and I took our inevitable constitutional’), he kicked the round ball around with friends in the park, went with his mother to see Rachmaninov in concert (Alf remembered that he looked like a ‘big bear’ huddled over the keyboard), tried conjuring, juggling (‘the house has resonated with the sound of falling balls tonight’), tried muscle-building with chest-expanders and hand-squeezers, joined Yoker Tennis Club, watched Rangers, watched Celtic, watched Yoker Athletic, had a notion to read the Bible (for the meaning and the beauty of the words), took up hitting the ‘wee white ball’ with a club (‘In the morning, I played golf. In the afternoon, I played golf. In the evening, I played golf’), trained in various athletics disciplines (hurdles, javelin, discus) and took up fretwork. He carried on ‘piano-walloping’, albeit informally, being inspired by the new music coming in from America.

I’ve taken a notion to make myself a good jazz pianist as hitherto I’ve only played straight stuff. I think I’ll send to Uncle Bob [in Sunderland] and ask him for a loan of his book on jazz playing.

Alf’s Sunderland relatives also kept him liberally supplied with the local newspapers so he could follow the fortunes of Sunderland AFC, with their exultant highs:

28 January 1933: Oh boy, oh boy! What a day! Why weren’t these spaces made bigger. Sunderland have defeated Aston Villa, by three goals to nothing at Villa Park! Aston Villa, the greatest cup-fighting team in England, the team whose name is a household word and whose traditions are more glorious than any other club in England. And Sunderland, who had met them umpteen times before in the cup without success, licked them!

And their inevitable lows:

8 March 1933: Eheu! I am plunged into the very depths of despondency. Life to me dark and gloomy and the future looms up, forbidding and hopeless – Sunderland have been defeated by Derby County at Roker Park in the cup-tie before the semi-final … Oh, it is sickening!

There was also going to the cinema. Since Pop was still playing piano in the intervals at cinemas, Alf got complimentary tickets, particularly for the 2000-seat art deco Commodore at 1297 Dumbarton Road, which opened on Boxing Day 1932. The programme for the first evening, attended by the Wights, was:

Our Managing Director, Mr GEORGE SINGLETON,

has a few words to say.

********

PARAMOUNT NEWS – A Pictorial Review of Daily Events

********

MICKEY’S ORPHANS – Mickey Mouse at it Again!

********

PATHETONE WEEKLY – To interest, to educate and to amuse

********

SLIPPERY PEARLS

A real novelty with over twenty well-known artistes in the cast including Laurel and Hardy; Wheeler and Woolsey; Joe E. Brown; Buster Keaton; Norma Shearer; Joan Crawford; William Beery; etc

********

THEN and NOW

Remember the good old days? This is the kind of film we used to entertain you with around 1912 and the musical (?) accompaniment is as near to the real thing as we care to remember.

********

MESSRS. PARAMOUNT FILM SERVICE LTD.

PRESENTS

MARLENE DIETRICH: CLIVE BROOK

Supported by

Anna May Wong: Warner Oland

And Eugene Pallette

In

THE SHANGHAI EXPRESS

Based on the story by Harry Hervey.

Directed by Josef von Sternberg

‘A’ Certificate

There were continuous performances each evening from 6.15 until 10.45, and on Saturday from 2.30 until 11 pm. In the manner of the medieval London apprentices who were fed so much salmon that they tired of the luxury, Alf surfeited on cinema, writing in his diary: ‘Oh! Pictures again.’ He didn’t like Grand Hotel with Greta Garbo, who he thought should be ‘put in a lunatic asylum and kept under close observation’. Otherwise, 1933 was a good year for the movies: Popeye made his spinach-slurping bow, the Marx Brothers were in Duck Soup, Laurel and Hardy pretended to be Sons of the Desert, and Mae West put her best chest forward in She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel, both with Cary Grant. But even Glaswegians without ‘comp’ tickets went to the cinema, on average three times a week; everywhere else in Britain, the average was once a fortnight. The warmth of the cinema, and that touch of luxury in a hard life, was no doubt as big a draw as the escapism shown on the silver screen.

Just after his fourteenth birthday Alf asked a girl out to the cinema; on the way into Glasgow on the tram, he asked for a penny ticket and handed over a half-crown piece (2/6d). Annoyed at being given so large a coin for so small a fare, the conductor took revenge by giving Alf the change in 58 halfpennies. This left Alf at the cinema kiosk, to his red-faced embarrassment, laboriously counting out the two shillings for the tickets in the conductor’s ha’pennies, thus holding up the queue. Alf claimed that it was four excruciating years before he plucked up the courage to ask another girl for a date. And so, thwarted in puppy love, Alf was back to hanging around with his mates.

Like many of his Yoker friends, Alf was a member of the Boys’ Brigade, then in its heyday. The Boys’ Brigade was formed in Glasgow in 1883, when William Alexander Smith surveyed his pubescent unruly pupils at the Sabbath School of the Free College Church in Hillhead. About to finally despair of his inability to interest or control the class, Smith had a notion: He was also an officer in the 1st Lanarkshire Rifle Volunteers, so why not use military methods (principally drill and discipline) and values (obedience and self-respect) to run the church Sunday youth club? As Smith expressed it later, his object was ‘the advancement of Christ’s Kingdom among boys and the promotion of habits of Reverence, Discipline, Self-Respect, and all that tends towards a true Christian Manliness’.

The Free College Church’s minister, Reverend George Reith, gave his enthusiastic backing. (Reith was the father of John Reith, who became the first Director-General of the BBC – thus Glasgow gave the world the inventor of the television in John Logie Baird, the overseer of television’s most famous station, and the creator of one of television’s most successful series.)

Realizing that a full uniform would be beyond the pockets of most of the boys’ parents, Smith developed an 18d outfit of a ‘pill box’ forage cap, a belt, a haversack and a badge, on which was struck an anchor and the motto ‘Sure and Steadfast’, taken from Epistles to the Hebrews, chapter 6, verse 19 (‘Which hope we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and steadfast’). In this minimalist uniform, Smith’s volunteers drilled, prayed, sung hymns and studied the Bible each Sunday at the Woodside Road Mission Hall. In pursuit of the ‘manliness’ in ‘Christian manliness’, Smith arranged swimming sessions, cricket, gymnastics with dumbbells and Indian clubs. It was intrinsic to the age that a healthy body and healthy mind were symbiotic. A Club Room supplied board games, religious readings, as well as Boy’s Own classics, many of them supplied free by Glasgow publisher Blackie and Son, including Kidnapped, The Black Arrow and Ben-Hur.

Fifty-nine boy volunteers attended the inaugural parade of the 1st Glasgow Company of The Boys’ Brigade on 4 October 1883. Some 20 dropped out when it became clear that Smith was a stickler for discipline – any boy even a minute late for 8 am parade was not allowed to ‘fall in’ – but the Boys’ Brigade became a wild success in that sector of Glasgow working-class society that believed most soberly in ‘getting on’. People like the Wights of Dumbarton Road.

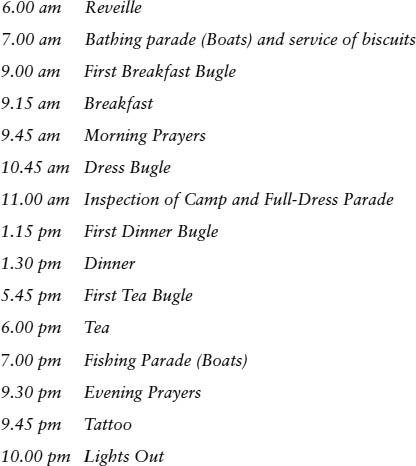

One of the prime attractions of the ‘BB’ for boys was the annual summer camp in the same week as Glasgow’s Fair Holiday, when the entire city’s heavy industry shut down for the duration. The general routine for the day, which did not change for decades, was:

In between the parades and prayers, there was plenty of time for sport and recreation. BB camps were one of the places that Alf improved the backhand that allowed him in his twenties, armed with a Slazenger tennis racket, to reach the West of Scotland men’s doubles final with his partner Colin Kesson.

By 1933, the Brigade’s jubilee year, the movement had spread across Britain and the globe; in Britain alone 111,871 British boys were enrolled, plus 52,219 in the associated Life Boys. The Brigade’s jubilee Conventicle, held at Hampden Park, was the largest open-air service held in Britain, with 130,000 inside the stadium, and 100,000 without. The sun shone all day.

For many city boys, the ‘BB’ summer camp, which was usually at Loch Fyne or North Berwick, was their one and only holiday. Not for Alf Wight. At Easter 1933 he attended a camp organized by Yoker church’s Sunday Club (at which an inspiring speech by the commandant left him and his friends ‘with a new determination to be decent fellows to the best of our ability’) and during the summer he enjoyed a holiday at West Kilbride, staying alone with friends of the family. After several days purely in the company of Dorothy Ash and Evelynne Sorley, Alf’s diary is filled with Wodehousian comic detail:

18 July:

Allah be praised! This afternoon, Dorothy introduced me to a lad by the name of Monty Gilbert – he seems a decent spud. We went down for a bathe immediately. He’s interested in all the things I like – sport, athletics, physical culture, and besides can talk seriously too. If I hadn’t met him, I’m sure my reason would have broken down under the strain of gallivanting around with a couple of females.

19 July:

In the morning, Monty and I had a glorious swim and sunbathe down at Ardneil Bay. It was the life. In the afternoon, we went into Saltcoats for a swim in the pool. There we met Do [orothy] and went afterwards to Mrs Duncan’s house for tea. After tea, we went into the drawing room to see Mr Duncan’s cine-kodak films. One of them, which was taken last year, showed Dorothy acting the goat. It was a scream and Monty and I just lay back and howled…

Friday 21:

Another day of sunbathing and swimming, very like yesterday. Monty is a great lad. I wish he lived in Glasgow for I believe he’s the sort of fella I’d like for a friend. David Sommerville seems to be cracked over Evelynne, the poor fish; he mopes about and can’t go anywhere without her. He’s the laughing-stock of the place, and I believe he knows it. I was at a garden party with Do. And I won the tennis tournament. Beat Dorothy in the final – it took me all my time too. D. Also won the treasure hunt, so we more or less cleared the board between us.

Tuesday 25:

Knocked out of the [tennis] tournament alas! I was beaten 6-3 – anyway I’ve nothing to bother me now. I bathed with Monty in the afternoon. I had the usual evening – a walk and then listened to the wireless. I haven’t much to say tonight so I’ll conclude the entry with a few remarks on various people. Evelynne has dropped down to zero in my estimation as I have found she is a tale-bearing, petty and deceitful little wretch. In short, a nasty bit of work. As to Dorothy, although she exasperates and irritates me terribly with her headstrong childish ways, she appears to be very straight and open. So Monty and I regard her as a fairly decent spud.

Friday 28:

The weather was a treat so the ‘gang’ spent morning and afternoon at Ardneil Bay. It was marvellous! In the evening Monty and I went to Saltcoats and visited a cinema. We saw a really first-class show – a British picture called ‘Sherlock Holmes’. We had a good blether on the road home.

After nearly three weeks at West Kilbride, Alf’s mother, father and Don came to take him home to Dumbarton Road. There he suffered ‘a holiday ache’, a nostalgia for West Kilbride. But not for long; a day later, he went with his parents to Sunderland for the marriage of his cousin Stan Wilkins. (Sunderland, incidentally, offered more than kin to the Wights; the Roker and Fullwell areas were the seaside, bathers and cafes, sand and hot pies, and the Wights often holidayed there.) After Sunderland, Alf was off with his mother to Arran on the Firth of Clyde, where well-to-do Glasgow liked to spend the summer, before attending the BB camp at Loch Fyne. And then back to West Kilbride.

But Alf’s life was not all one long holiday.

The year before, 1932, Alf had contracted diphtheria. One reason for the sheer exhilaration he felt – and communicated in his diary – on his holiday in 1933 was the sheer relief of being alive.

Caused by the bacteria Corynebacterium diphtheria, the disease produces a grey film (diphtheria is Greek for ‘a piece of leather’) that can block the airways. Meanwhile, the toxins produced by the bacteria produce skin boils and lesions, as well as infiltrate the bloodstream to reach the organs.

Queen Victoria’s daughter Alice and granddaughter Marie of Hesse both died from diphtheria, but it is mainly a disease of the crowded city street, not the spacious palace, because it is spread by droplets. Tenement Glasgow, with the highest population density in Western Europe, bred diphtheria as though it was some maniacal laboratory; during the period 1934–42 alone, 1210 Glaswegians died from the disease. Alf suffered from diphtheria abscesses over his body for two years after contracting the disease.

Inevitably, the brush with death affected Alf. His decision, whether taken consciously or unconsciously, to keep a diary in 1933 was a life-affirming gesture, a young boy’s bid for immortality. His natural enthusiasm for life was increased; a prime new enthusiasm, unsurprisingly, was keeping fit. Along with many a boy in the 1930s, he turned to Lieutenant J. P. Muller for guidance on how to keep the body beautiful and healthy.

The name of Jurgen Peter Muller is now forgotten, but before the Second World War he was a major – and perfectly toned – figure on the cultural landscape of Europe. (The principal of Glasgow School of Art, where Muller appeared during a lecture tour in 1911, declared Muller’s body the most perfect he had ever seen.) Born in 1866 in Asserballe, Denmark, Muller had been so small as a baby that ‘I could be placed in an ordinary cigar box’. He almost died of dysentery at two and ‘contracted every childhood complaint’ thereafter. During his teens, however, he improved his health by a strict regimen of exercises. In other words, he triumphed over puniness and sickliness by his own efforts, and not by the benefit of inherited genes. Eventually, in 1904, Muller put down his regimen in words. With its distinctive cover picture of Apoxyomenos, the Greek athlete, naked and towelling himself, My System: 15 Minutes’ Exercise a Day for Health’s Sake went on to sell 2 million copies and to be translated into 25 languages. Muller himself eventually settled in London, where he opened the Muller Institute at 45 Dover Street and dropped the umlaut from his name in order to make it seem less German. Business boomed. The Prince of Wales gave Muller his official imprimatur, the British Army adopted his fitness regime, and Muller added to his catalogue with My System for Women, My System for Children, My System of Breathing, The Daily Five Minutes and My Sunbathing and Fresh Air System, among others. The cult of ‘Mullerism’ swept Europe, and the man himself became the Dane more famous than Hans Christian Andersen. In recognition of his services to physical health (and to raising Denmark’s international profile) the King of Denmark conferred a knighthood of the Order of the Dannebrog on Muller.

‘Why be weakly?’ asked My System, before answering with a regimen that involved a suitable diet, sensible underclothes (less was best, contra the Victorian fashion for corsets), moderate indoor temperatures, eight hours’ sleep a night, and a quarter of an hour of exercises daily. These exercises were preferably undertaken whilst wearing few clothes and deep-breathing fresh air (outdoors or in front of an open window were the best locations for the System). The first eight exercises advocated by Muller were essentially gymnastic or balletic stretches, including Slow Trunk-Circling, Quick Leg-Swinging, Quick Arm-Raising, and were ended with a cold bath and a vigorous towelling. Then followed ten exercises of muscular stretching whilst simultaneously rubbing the body. Muller wrote:

The rubbing is done with the palms of the hands, and should be a simple stroking or friction to begin with; later on, as one’s strength increases, it should be so vigorous that it becomes a sort of massage … After you have followed up my System for some time, the skin will assume quite a different character; it will become firm and elastic, yet as soft as velvet and free from pimples, blotches, spots or other disfigurements.

Like other early twentieth-century physical culturalists such as Joseph Pilates, Muller believed that his gymnastic exercises had definite medical benefits and could treat everything from acidity to writer’s cramp, including the devastations of old age. In an era of rampant infection, Muller’s insistence that anybody could best disease by exercise, fresh air and sunlight was engaging. Before antibiotics, Muller’s prescription for fresh air was one of the few preventative measures people could take to ward off TB. (Muller had once worked as an inspector at the Vejlefjord Tuberculosis Sanitorium and he went on to become one of Denmark’s leading athletes.) But there was more to Muller’s system than mere physicality; philosophically, it was aimed at the individual and was open to anybody. In an age of rampant political extremism, other gymnastic movements were tinged with nationalist or Communist tones. The Muller method needed neither expensive equipment nor membership of a political organization. Other ‘Mullerists’ included the arch-individualist of the twentieth century, Franz Kafka.

Alf Wight did his Muller regime even on school mornings in winter:

Diary, 9/1/33:

Back to the old school routine again. Up at 7.45. BRR! Exercises and cold bath and a final exhilarating dash after my car [tram].

Diary, 12/1/33:

It took a bit of willpower to get me into the cold bath this morning as it was cold enough to freeze the whiskers off a monkey.

It was also too cold, Don decided, to leave the kitchen couch. After months of ‘Mullering’, however, Alf was able to report in his diary on 20 April 1933:

I’m feeling as fit as the proverbial fiddle. I put it all down to the exercises and cold baths. I am much brighter and healthier than I was last year before my illness and I seem to be on the upgrade.

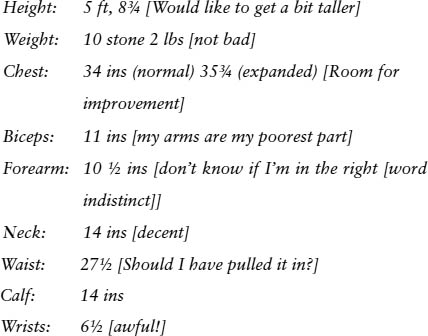

He also ‘set down my figures’ in his diary with the intention of improving on them:

He thought the diphtheria cost him a place in the rugby first XV, but there was always summer sports to shine at, and he decided that ‘I am going to enter everything within my scope at sports day, that is, the 100 yards, 220 yards, broad jump … discus, javelin, hurdles, cricket-ball, and place and drop kick. I’m leaving the long distances alone.’

A certain McKechnie was slated to win everything, but Alf decided ‘I am going to do something about it. I used to be able to beat him in the 100 yards and last year I did 19 ft. in the long jump so I start training tomorrow, full of hope.’ A pulled muscle put paid to Alf’s intended track and field glories, but he kept up the Muller regime for years. When his own son, Jim Wight, went to Glasgow veterinary school, he gave him a copy of My System.

Alf’s illness affected his academic performance at school – he lost more than a month of lessons in the Michaelmas (autumn) 1932 term – but fortunately only by degree, not by kind. His final marks on his record card show ‘Eng. 67, Hist. 52, Latin 48, French 53, Maths 40’ and in the ‘School Honours’ column his award of ‘Leaving Cert [ificate]’ is noted. Alf Wight left Hillhead High on 30 June 1933 with Higher Passes in English, Latin and French and Lower passes in History and, miraculously, even Maths. He wrote in his diary:

What a day! What a day! I awoke this morning a poverty-stricken youth, and am going to bed a rich man. This morning, we had the prize-giving and I got 4/6d for being runner-up in the championship and then took my departure from Hillhead, and all the pleasant things connected with it but on the other hand, I’m glad to have got my higher at the age of 16 yrs and 8 months and to be able to get on with my job. I’ll join the F.P. [Former Pupils] Club of course, and keep up my connection with the school. In the evening, Curly and I went to the Commodore with the complimentary ticket, and saw an excellent programme. Afterwards, Mother presented me with ten bob for getting my highers.

His parents must have believed that their efforts had been worth it. As always he had been a model pupil, and was marked ‘Ex[cellent]’ in Progress, Diligence and Conduct.

His report card also clearly noted Alf’s reason for leaving.

‘Gone to Veterinary College.’